Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cyprus Police

View on Wikipedia

| Cyprus Police Greek: Αστυνομία Κύπρου Turkish: Kıbrıs Polisi | |

|---|---|

Cyprus police logo | |

| Motto | Ανθρώπινη και Υπερήφανη (Humane and Proud) |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1960 |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| National agency | CY |

| Operations jurisdiction | CY |

| |

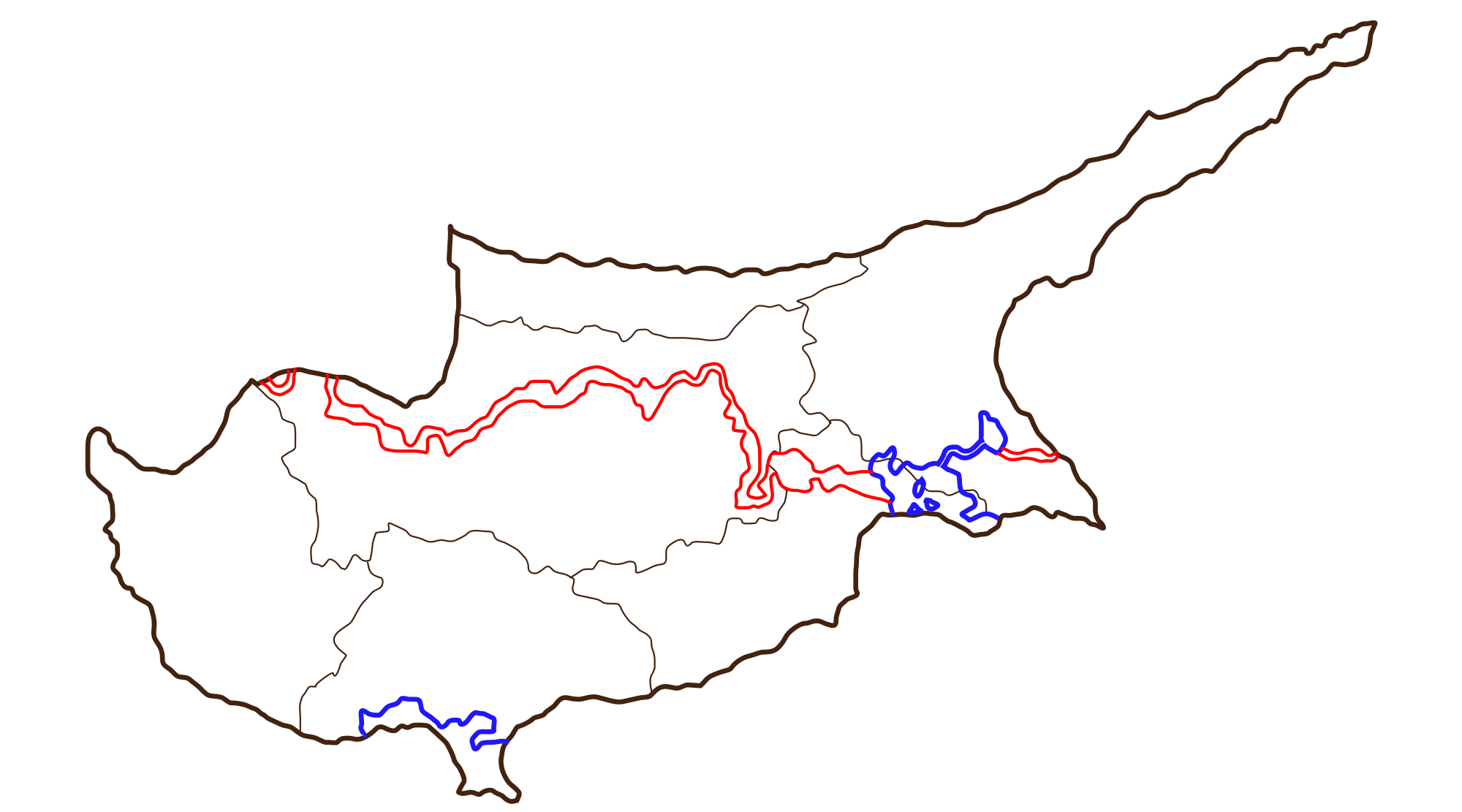

| Above: Northern part of the island currently not policed by the Republic of Cyprus as it is under the de facto control of Northern Cyprus. Outlined in red is the UN buffer zone and outlined in blue are the areas of the British Sovereign Bases. Below: Relief map of Cyprus showing mountains and sea. Red dot indicating capital and Headquarters location. | |

| Size | 9,251 km2 total Areas Cyprus Police does not operate in 3,355 km2 occupied area (North) 346km² UN buffer zone 254km² British Sovereign Bases[1] |

| Population | 956,000 [2] |

| Primary governing body | Republic of Cyprus |

| Secondary governing body | Ministry of Justice and Public Order (Cyprus) |

| Constituting instruments | |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Overseen by Government Agency | Independent Authority for the Investigation of Allegations and Complaints against the Police[4] |

| Headquarters | Antistratigou Evaggelou Floraki Str., Aglantzia, Nicosia, Cyprus |

| Police officers | 4927 (data taken on 01/01/2019) [2] |

| Specialized posts | 92 |

| Minister responsible |

|

| Agency executive |

|

| Facilities | |

| Police stations | 50[6] excluding substations, offices, units etc. |

| Airbases | 1[7] |

| Boats | 5 fast sea patrol boats 5 patrol boats 6 rigid inflatable boats[8] |

| Helicopters | 2 Bell 412EP 2 AgustaWestland AW139[7] |

| Website | |

| http://www.police.gov.cy/ | |

| Emergency Telephone Number 112 or 199 Citizens' line 1460 Narcotics line 1498 Hunters' line 1414 Fire report line 1407 Rescue Coordination Center 1441 | |

The Cyprus Police (Greek: Αστυνομία Κύπρου, Turkish: Kıbrıs Polisi), is the national police service of the Republic of Cyprus, falling under the Ministry of Justice and Public Order since 1993.[9]

The duties and responsibilities of the Cyprus police are set out in the amended Police Law (N.73(1)) of 2004 and include the maintenance of law and order, the prevention and detection of crime, as well as arresting and bringing offenders to justice.[10]

History

[edit]Although the history of Law enforcement in Cyprus goes back to 1879 when the first Police Law was passed by the then British Colonial Government, which operated a mounted gendarmerie force known as the Cyprus Military Police, the history of the Cyprus Police begins with the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus in 1960.

In 1960 two Public Security Forces were established within the framework of the Constitution: the Police Force, which was responsible for policing the urban areas, and the Gendarmerie, which was responsible for policing rural areas. A Greek-Cypriot Chief and a Turkish-Cypriot Chief administered the two Forces respectively.[11]

The two forces of the police were joined to form the present police service during the year 1964, shortly after the intercommunal troubles between the Greek and the Turkish communities, as a result of which the Turkish Cypriot officers abandoned their posts.[9] Additionally the conflict created great problems for the police, who had to handle the situation, along with the then sparsely manned Cypriot Army, because it was the only organized force.

With the creation of the Cypriot National Guard in 1964, the duties of military nature were transferred to the National Guard and the police was limited back to its usual duties.[12]

Also notable is that a museum dedicated to the history of the Cyprus Police and Law enforcement in Cyprus in general exists, with a history of its own. The Cyprus Police Museum, owned by the Cyprus Police and managed by the Department A' of the Police Headquarters is open to the general public.

Authorities

[edit]The Cyprus Police operates and exercises its authorities throughout the territory of the Republic of Cyprus based on the following Laws and Regulations:[3]

- The Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus

- Police Law (N.73(I)/2004)[13]

- Police Regulations

- Police Standing Orders

- Criminal Code Cap.154

- Criminal Procedure Law Cap.155

- Evidence Law Cap-9

- The Processing of Personal Data (Protection of the Individual) Law 138(1)/2001

The legal framework within which the Cyprus Police exists and operates is determined by the Constitution, Police Law Cap.285 and other laws that provide the authority for investigation, detention, arrest, questioning and prosecution of offenders of the Law.

Structure and organisation

[edit]The structure and organisation of the Cyprus Police is governed by Police Ordinance 1/10 and is formed as stated below:[14]

Headquarters

[edit]The Police Headquarters is divided into different Departments/Directorates/Services and Units, each specializing in a different field/aspect of policing.

Departments

[edit]- Department A' (Administration)

- Department B' (Traffic, Transport)

- Department C' (Criminal Investigations, Prosecutors)

- Department D' (Scientific & Technical Support)

- Research and Development Department

Directorates

[edit]- European Union & International Police Cooperation Directorate

- Materials & Supplies Management Directorate

- Airports Security Directorate

- Finance Directorate

- Directorate of Professional Standards

Services

[edit]- Aliens & Immigration Service

- Drug Law Enforcement Service

- Forensic Investigations Service

- Audit & Inspection Service

- Central Intelligence Service

Units

[edit]- Cyprus Police Academy

- Emergency Response Unit

- Presidential Guard Unit

- Port & Marine Police

- Cyprus Police Aviation Unit (Previously named Police Air Wing)

Divisions

[edit]

The Cyprus Police has one Division for each district of Cyprus. Under this divisions are the Police Stations but also within each Police Division, branches can be created similar to the branches of the Police Headquarters. For example, there is a Headquarters Drug Law Enforcement Service but also a Nicosia, Limassol etc. Drug Law Enforcement Service. Other examples include Headquarters Criminal Investigation Department (C.I.D.)- Larnaca, Nicosia, Limassol etc. C.I.D. and Headquarters Traffic Department - Nicosia, Limassol etc. Traffic Department . The difference is that the Headquarters units/services etc. operate throughout the territory of the Cyprus Republic while the divisional (provincial) units/services operate mostly within the District that are located.[15]

- Nicosia

- Limassol

- Larnaca

- Famagusta

- Paphos

- Keryneia

- Morphou

- Fire Service - The Fire Service used to operate as an independent Division based in Nicosia but with national coverage up to 15/10/2021 that was established as an independent service.[16]

Because of the Turkish invasion and continuing occupation, the Police Divisional Headquarters of Famagusta and Morphou are temporarily housed in Paralimni and Evrychou respectively, while the Kyrenia Police Division has temporarily suspended its operation.[17]

Ranks of the Cyprus Police

[edit]| Title | Chief constable |

Deputy chief constable |

Assistant chief constable |

Chief superintendent |

Superintendent A |

Superintendent B |

Chief inspector |

Inspector |

Senior sergeant | Sergeant | Acting sergeant / Senior Constable | Acting Sergeant | Senior constable | Constable |

Special constable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insignia |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Equipment

[edit]Vehicles

[edit]Markings

[edit]Cyprus Police cars are white with a blue stripe that goes around the car. On both sides they have printed on them the words POLICE and ΑΣΤΥΝΟΜΙΑ, which means Police in Greek. They also have the logo of the Cyprus Police, usually on the front doors and also have printed on them the Police's website www.police.gov.cy. An exception to this is some of the cars used by the Neighbourhood Police that have the Neighbourhood Police logo instead of the Cyprus Police Logo. On the front part of the car they have again the logo with the words POLICE and ΑΣΤΥΝΟΜΙΑ and at the back they could have, depending on the model of the car and the space available, the words Police in Greek and English or just the Cyprus Police insignia or both. On the roof they have printed a distinct number for each one as aerial roof markings.

In 2011 a trial version for new markings was used on an old Opel Vectra patrol car. These were half-Battenburg markings with a highly reflective blue-yellow stripe on the sides instead of the solid blue stripe. Additionally the back was covered in reflective yellow-red diagonal stripes and had printed the emergency phone number 112. The front part on the hood of the car had the words ΑΣΤΥΝΟΜΙΑ and POLICE printed inverted so that they would appear correctly when seen through a mirror. These markings were not enforced.

In 2012 new markings were enforced were the blue stripe although still solid was replaced with a highly reflective one, and the rear horizontal line was replaced from a solid blue stripe to a blue-white diagonal line similar to the rear usually found on vehicles with Battenburg markings.

The Cyprus Police also uses unmarked vehicles. Unmarked vehicles are not necessarily covert to be used for undercover work. Most unmarked cars are the same models as the patrol cars and they are mostly used by plain clothed officers such as crime investigators, crime prevention squads, technicians etc. Most of these cars are fitted with sirens and can be seen in the streets with detachable strobe lights.

Lists of vehicles

[edit]*Unless specifically referenced, the dates the vehicles entered service are based on their license plate registration numbers

| Year entered service* |

Motorcycle | Photo | Manufacturer | Production Model |

Engine | Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honda CBX750 | 750cc |

Traffic/Response vehicle | |||||

| Suzuki GSX 750P | 750cc |

Traffic/Response vehicle | |||||

| Honda Pan-European | 1100cc |

Traffic/Response vehicle | |||||

| Suzuki GSX-R1000 | 1000cc |

Traffic/Response vehicle | |||||

| Suzuki V-Strom 1000 | 1000cc |

Traffic/Response vehicle | |||||

| KTM 640 Adventure | 625cc |

Traffic/Response vehicle | |||||

| BMW C1 | Neighbourhood Police | ||||||

| Honda CBR1000RR |  |

1000cc |

Traffic/Response vehicle | ||||

| Honda Varadero |  |

1000cc |

Traffic/Response vehicle |

*Unless specifically referenced, the dates the vehicles entered service are based on their license plate registration numbers

Aerial vehicles

[edit]Boats

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]Cyprus police has been the main feature and appeared in television shows such as:

- "Εσύ Στον Κόσμο Σου", which was a series on ANT1 revolving around a family with the main protagonist being a police officer and showing multiple investigations, mainly organised crime.[19]

- "Στα Όρια" which was a series based on fictional investigations by a team police officers, shown on RIK.[20]

- "Κάρμα" which was a television series on Alpha TV, based on real criminal events that have happened in Cyprus.[21]

Gallery

[edit]-

Cyprus Police Aviation Unit Bell 412EP participating in fire fighting efforts in Israel, during the 2010 Mount Carmel forest fire

-

Cyprus Port and Marine Police jet F.P.B. (Fast sea Patrol Boat)

See also

[edit]- Cyprus Civil Defence

- Cyprus Fire Service

- Cyprus Joint Rescue Coordination Center

- Cyprus Police Academy

- Cyprus Police Aviation Unit

- Cyprus Police Museum

- Cyprus Port & Marine Police

- Cyprus Prisons Department

- Hellenic Police

- Sovereign Base Areas Customs

- Sovereign Base Areas Police

- Cyprus Joint Police Unit

References

[edit]- ^ List of countries and outlying territories by total area#cite note-60

- ^ a b "Αστυνομία Κύπρου".

- ^ IAIACAP Official Website "Welcome Page". Retrieved 31 Jan 2012.

- ^ Cyprus Police official website "Chief of Police CV".

- ^ Cyprus Police kfficial website "Useful Telephones". Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 31 Jan 2012.

- ^ a b Cyprus Police kfficial website "Cyprus Police Aviation Unit". Retrieved 31 Jan 2012.

- ^ Cyprus Police official website "Police Border Marine". Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 31 Jan 2012.

- ^ a b "Defence – Security – Police". Cyprus Government web portal. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ Cyprus Police lfficial website"Mission". Archived from the original on 6 April 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Cyprus Police Official Website"Historical Background". Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ Κυβερνητική Πύλη ΔιαδικτύουΆμυνα - Ασφάλεια - Αστυνομία (in Greek). Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Police Law (N.73(I)/2004)Ο Περί Αστυνομίας Νόμος του 2004 (73(I)/2004) (in Greek), 2004

- ^ Police Ordinance 1/10 Οργάνωση της Αστυνομίας και Καθήκοντα των Μελών της (in Greek), Cyprus Police, 6 April 2012, p. 21

- ^ Cyprus Police Official Website "Nicosia Police Division". Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 31 Jan 2012.

- ^ CyLaw "Ο περί Πυροσβεστικής Υπηρεσίας Νόμος του 2021 (100(I)/2021)". Retrieved 4 Dec 2021.

- ^ Cyprus Police Official Website "Composition". Archived from the original on 6 April 2007. Retrieved 31 Jan 2012.

- ^ Politis Sports"H CHEVROLET ΣΥΜΒΑΛΛΕΙ ΣΤΟ ΘΕΣΜΟ Matiz, "Αστυνομικός της Γειτονιάς!"". Politis. 21 January 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 12 Sep 2012.

- ^ "Εσύ στον κόσμο σου: Επιστρέφει με νέα πρόσωπα – Όσα θα δούμε στα πρώτα επεισόδια". tothemaonline.com (in Greek). Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ "Στα Όρια: Πρεμιέρα εμπνευσμένη από την υπόθεση «Ορέστης»". 2023-09-23. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ "ΚΑΡΜΑ | AlphaCyprus". www.alphacyprus.com.cy. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

External links

[edit]Cyprus Police

View on GrokipediaEstablished in 1960 coinciding with Cyprus's independence from British colonial rule, the force initially comprised two separate entities under the Zurich-London agreements—a Greek Cypriot-led urban Police Force and a Turkish Cypriot-led rural Gendarmerie—which were merged into a unified Cyprus Police in 1964 following the withdrawal of Turkish Cypriot personnel amid intercommunal clashes.[1]

Overseen by the Ministry of Justice and Public Order, it operates under a Chief of Police supported by four Assistant Chiefs responsible for administration, operations, training, and support services, with organizational units including six district divisions, specialized departments for crime combating, traffic enforcement, immigration control, and maritime policing, as well as the integrated Fire Service.[2][3]

As a member of Interpol since 1962, the Cyprus Police collaborates internationally on cross-border crime, while domestically it has faced scrutiny over isolated incidents of alleged excessive force, such as beatings of detainees reported by human rights monitors and use of crowd control measures during protests, prompting internal professional standards directorates and external oversight efforts to address accountability.[4][5][6]