Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Calanoida

View on Wikipedia

| Calanoida | |

|---|---|

| |

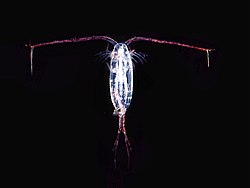

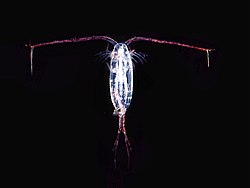

| Unidentified species of copepod in the order Calanoida. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Copepoda |

| Infraclass: | Neocopepoda |

| Superorder: | Gymnoplea Giesbrecht, 1882 [1] |

| Order: | Calanoida Sars, 1903 |

| Families | |

|

See text | |

Calanoida is an order of copepods, a group of arthropods commonly found as zooplankton. The order includes around 46 families with about 1800 species of both marine and freshwater copepods between them.[2]

Description

[edit]Calanoids can be distinguished from other planktonic copepods by having first antennae at least half the length of the body and biramous second antennae.[2] However, their most distinctive anatomical trait is the presence of a joint between the fifth and sixth body segments.[3] The largest specimens reach 18 millimetres (0.71 in) long, but most do not exceed 0.5–2.0 mm (0.02–0.08 in) long.[2]

Classification

[edit]The order Calanoida contains the following families:[4]

- Acartiidae

- Aetideidae

- Arctokonstantinidae

- Arietellidae

- Augaptilidae

- Bathypontiidae

- Calanidae

- Candaciidae

- Centropagidae

- Clausocalanidae

- Diaixidae

- Diaptomidae

- Discoidae

- Epacteriscidae

- Eucalanidae

- Euchaetidae

- Fosshageniidae

- Heterorhabdidae

- Hyperbionycidae

- Kyphocalanidae

- Lucicutiidae

- Megacalanidae

- Mesaiokeratidae

- Metridinidae

- Nullosetigeridae

- Paracalanidae

- Parapontellidae

- Parkiidae

- Phaennidae

- Pontellidae

- Pseudocyclopidae

- Pseudocyclopiidae

- Pseudodiaptomidae

- Rhincalanidae

- Rostrocalanidae

- Ryocalanidae

- Scolecitrichidae

- Spinocalanidae

- Stephidae

- Sulcanidae

- Temoridae

- Tharybidae

- Tortanidae

Ecology

[edit]Calanoid copepods are the dominant animals in the plankton in many parts of the world's oceans, making up 55–95% of plankton samples.[2] They are therefore important in many food webs, taking in energy from phytoplankton and algae and 'repackaging' it for consumption by higher trophic level predators.[2] Many commercial fish are dependent on calanoid copepods for diet in either their larval or adult forms. Baleen whales such as bowhead whales, sei whales, right whales and fin whales rely substantially on calanoid copepods as a food source.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ J. W. Martin & G. E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Mauchline, John (1998). "Introduction". The Biology of Calanoid Copepods. Advances in Marine Biology. Vol. 33. Elsevier. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-12-105545-5.

- ^ Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Holt-Saunders International. p. 692. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Calanoida". www.marinespecies.org. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

External links

[edit] Media related to Calanoida at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Calanoida at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Calanoida at Wikispecies

Data related to Calanoida at Wikispecies- Calanoida fact sheet – guide to the marine zooplankton of south eastern Australia

- Classification of Calanoida

- Key to calanoid copepod families