Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

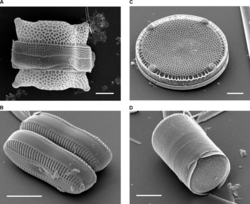

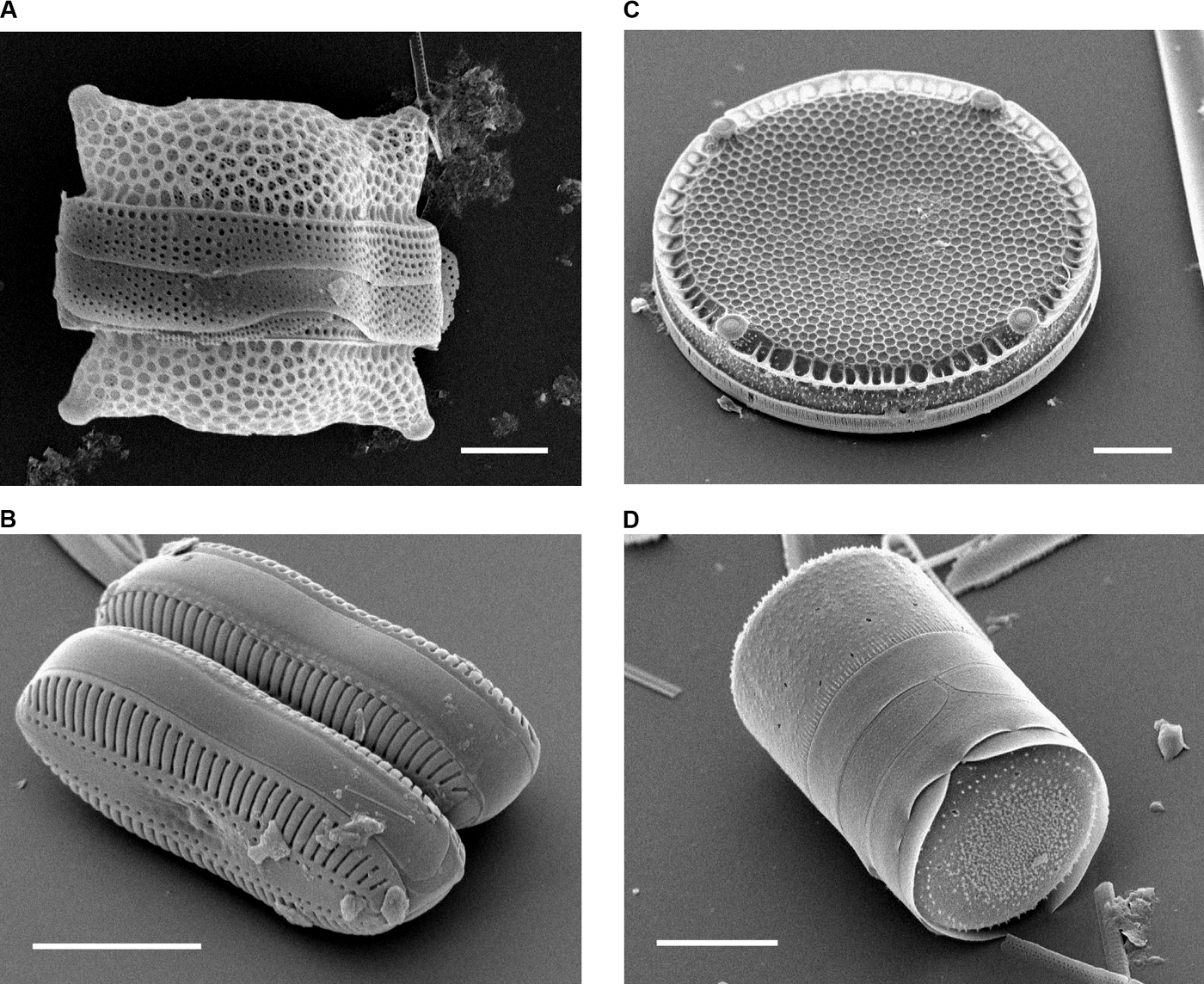

Frustule

View on Wikipedia

A frustule is the hard and porous cell wall or external layer of diatoms. The frustule is composed almost purely of silica, made from silicic acid, and is coated with a layer of organic substance, which was referred to in the early literature on diatoms as pectin, a fiber most commonly found in cell walls of plants.[1][2] This layer is actually composed of several types of polysaccharides.[3]

The frustule's structure is usually composed of two overlapping sections known as thecae (or less formally as valves). The joint between the two thecae is supported by bands of silica (girdle bands) that hold them together. This overlapping allows for some internal expansion room and is essential during the reproduction process. The frustule also contains many pores called areolae and slits that provide the diatom access to the external environment for processes such as waste removal and mucilage secretion.

The microstructural analysis of the frustules shows that the pores are of various sizes, shapes and volume. The majority of the pores are open and do not contain impurities. The dimensions of the nanopores are in the range 250–600 nm.[4][5][6]

Thecae

[edit]| Part of a series related to |

| Biomineralization |

|---|

|

A frustule is usually composed of two identically shaped but slightly differently sized thecae. The theca which is a bit smaller has an edge which fits slightly inside the corresponding edge of the larger theca. This overlapping region is reinforced with silica girdle bands, and constitutes a natural "expansion joint". The larger theca is usually thought of as "upper", and is thus termed the epitheca. The smaller theca is usually thought of as "lower", and is thus called the hypotheca.[1] As the diatom divides, each daughter retains one theca of the original frustule and produces one new theca. This means that one daughter cell is the same size as the parent (epitheca and new hypotheca) while in the other daughter the old hypotheca becomes the epitheca which together with a new and slightly smaller hypotheca comprises a smaller cell.

Pseudoseptum

[edit]Some genera of diatoms develop ridges on the internal surface of the frustules which extend into the inner cavity. The ridges are commonly termed Pseudoseptum with the plural pseudosepta.[7] In the family Aulacoseiraceae, the ridge is more specifically called a ringleist or ringleiste.[8]

Diatom skeletons and their uses

[edit]When diatoms die and their organic material decomposes, the frustules sink to the bottom of the aquatic environment. This remnant material is diatomite or "diatomaceous earth", and is used commercially as filters, mineral fillers, mechanical insecticide, in insulation material, anti-caking agents, as a fine abrasive, and other uses.[9] There is also research underway regarding the use of diatom frustules and their properties for the field of optics, along with other cells, such as those in butterfly scales.[2]

Frustule formation

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2008) |

As the diatom prepares to separate it undergoes several processes in order to start the production of either a new hypotheca or new epitheca. Once each cell is completely separate they then have similar protection and the ability to continue frustule production.[10]

A brief and extremely simplified version can be explained as:[10]

- Following mitosis, two daughter cells form inside the parent cell, with the nucleus of each daughter cell moves to the side of the diatom where the new hypotheca will form.

- A microtubule center positions itself between the nucleus and the plasma membrane above which the new hypotheca will be placed.

- A vesicle known as the silica deposition vesicle forms between the plasma membrane and the microtubule center. This forms the center of the pattern and silica deposition can continue outward from that point, forming a huge vesicle along one side of the cell.

- A new valve is formed within the silica deposition vesicle by the targeted transport of silica, proteins, and polysaccharides. After formation the valve is exocytosed by fusion of the silica deposition vesicle membrane (the silicalemma) with the plasma membrane.

- The daughter cells fully separate, with the inner face of the silicalemma becoming the new plasma membrane.

- Following separation, the daughter cells generate girdle bands, allowing the cells to expand unidirectionally along the axis of cell division.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Diatoms: More on Morphology".

- ^ a b Parker, Andrew R.; Townley, Helen E. (3 June 2007). "Biomimetics of photonic nanostructures". Nature Nanotechnology. 2 (6): 347–353. Bibcode:2007NatNa...2..347P. doi:10.1038/nnano.2007.152. PMID 18654305.

- ^ Progress in Phycological Research: v. 7 (1991) by F.E. Round (Volume editor), David J. Chapman (Volume editor)

- ^ Reka, Arianit; Anovski, Todor; Bogoevski, Slobodan; Pavlovski, Blagoj; Boškovski, Boško (29 December 2014). "Physical-chemical and mineralogical-petrographic examinations of diatomite from deposit near village of Rožden, Republic of Macedonia". Geologica Macedonica. 28 (2): 121–126.

- ^ Reka, Arianit A.; Pavlovski, Blagoj; Makreski, Petre (October 2017). "New optimized method for low-temperature hydrothermal production of porous ceramics using diatomaceous earth". Ceramics International. 43 (15): 12572–12578. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.06.132.

- ^ Reka, Arianit A.; Pavlovski, Blagoj; Ademi, Egzon; Jashari, Ahmed; Boev, Blazo; Boev, Ivan; Makreski, Petre (31 December 2019). "Effect Of Thermal Treatment Of Trepel At Temperature Range 800-1200˚C". Open Chemistry. 17 (1): 1235–1243. doi:10.1515/chem-2019-0132.

- ^ "Pseudoseptum". Diatoms. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Ringleiste". Diatoms. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Diatom Frustule 2

- ^ a b Zurzolo, Chiara; Bowler, Chris (1 December 2001). "Exploring Bioinorganic Pattern Formation in Diatoms. A Story of Polarized Trafficking". Plant Physiology. 127 (4): 1339–1345. doi:10.1104/pp.010709. PMC 1540160. PMID 11743071.

External links

[edit]- Frustule on Britannica

- diatom frustule on astrographics.com

- Geometry and Pattern in Nature 1: Exploring the shapes of diatom frustules with Johan Gielis' Superformula, by Christina Brodie, UK

Regarding the Super formula

[edit]- Exploring the miniature world on microscopy-uk.org.uk

- Superellipse And Superellipsoid, A Geometric Primitive for Computer Aided Design, by Paul Bourke, January 1990

- Supershapes (Superformula) by Paul Bourke, March 2002