Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cyclopoida

View on Wikipedia

| Cyclopoida | |

|---|---|

| |

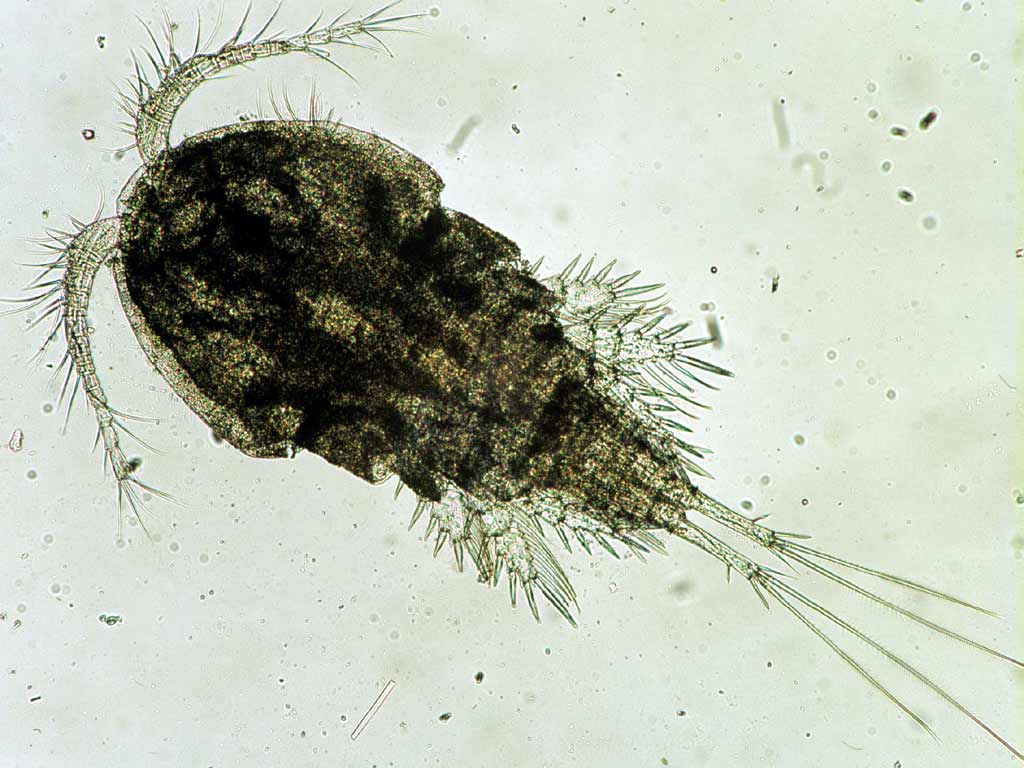

| Cyclops sp. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Copepoda |

| Infraclass: | Neocopepoda |

| Superorder: | Podoplea |

| Order: | Cyclopoida Burmeister, 1834 |

| Families | |

|

See text | |

The Cyclopoida are an order of small crustaceans from the class Copepoda. Like many other copepods, members of Cyclopoida are small, planktonic animals living both in the sea and in freshwater habitats. They are capable of rapid movement. Their larval development is metamorphic, and the embryos are carried in paired or single sacs attached to first abdominal somite.[1]

Distinguishing features

[edit]Cyclopoids are distinguished from other copepods by having first antennae shorter than the length of the head and thorax, and uniramous second antennae. The main joint lies between the fourth and fifth segments of the body.[2]

Taxonomy

[edit]Cyclopoida contains 30 families:[3]

- Archinotodelphyidae Lang, 1949

- Ascidicolidae Thorell, 1859

- Botryllophilidae Sars G.O., 1921

- Buproridae Thorell, 1859

- Chitonophilidae Avdeev & Sirenko, 1991

- Chordeumiidae Boxshall, 1988

- Corallovexiidae Stock, 1975

- Cucumaricolidae Bouligand & Delamare-Deboutteville, 1959

- Cyclopettidae Martínez Arbizu, 2000

- Cyclopicinidae Khodami, Vaun MacArthur, Blanco-Bercial & Martinez Arbizu, 2017

- Cyclopidae Rafinesque, 1815

- Cyclopinidae Sars G.O., 1913

- Enterognathidae Illg & Dudley, 1980

- Enteropsidae Thorell, 1859

- Fratiidae Ho, Conradi & López-González, 1998

- Giselinidae Martínez Arbizu, 2000

- Hemicyclopinidae Martínez Arbizu, 2001

- Lernaeidae Cobbold, 1879

- Mantridae Leigh-Sharpe, 1934

- Micrallectidae Huys, 2001

- Notodelphyidae Dana, 1853

- Oithonidae Dana, 1853

- Ozmanidae Ho & Thatcher, 1989

- Paralubbockiidae Boxshall & Huys, 1989

- Psammocyclopinidae Martínez Arbizu, 2001

- Pterinopsyllidae Sars G.O., 1913

- Schminkepinellidae Martínez Arbizu, 2006

- Smirnovipinidae Khodami, Vaun MacArthur, Blanco-Bercial & Martinez Arbizu, 2017

- Speleoithonidae Rocha & Iliffe, 1991

- Thaumatopsyllidae Sars G.O., 1913

- Cyclopoida incertae sedis – 8 genera

Several more families are included in suborder Poecilostomatoida, a temporary name for the "poecilostome lineage" [4] The Poecilostomatoida were previously treated as a separate order, but molecular phylogenies show that this lineage is nested within the Cyclopoida.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ J. K. Lowry (October 2, 1999). "Cyclopoida (Copepoda, Maxillipoda)". Crustacea, the Higher Taxa: Description, Identification, and Information Retrieval. Australian Museum. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 692. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ^ Geoff Boxshall & T. Chad Walter (2018). T. Chad Walter & Geoff Boxshall (ed.). "Cyclopoida". World of Copepods database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Geoff Boxshall & T. Chad Walter (2018). T. Chad Walter & Geoff Boxshall (ed.). "Poecilostomatoida". World of Copepods database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Khodami, S; McArthur, JV; Blanco-Bercial, L; Martinez Arbizu (2017). "Molecular Phylogeny and Revision of Copepod Orders (Crustacea: Copepoda)". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 9164. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.9164K. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06656-4. PMC 5567239. PMID 28831035. (Retracted, see doi:10.1038/s41598-020-74404-2, PMID 33057148)