Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Immortalised cell line

View on Wikipedia

| Immortalised cell line | |

|---|---|

| |

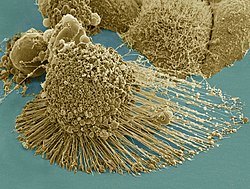

HeLa cells, an example of an immortalised cell line. DIC image, DNA stained with Hoechst 33258. | |

| Anatomical terminology |

An immortalised cell line is a population of cells from a multicellular organism that would normally not proliferate indefinitely but, due to mutation, have evaded normal cellular senescence and instead can keep undergoing division. The cells can therefore be grown for prolonged periods in vitro. The mutations required for immortality can occur naturally or be intentionally induced for experimental purposes. Immortal cell lines are a very important tool for research into the biochemistry and cell biology of multicellular organisms. Immortalised cell lines have also found uses in biotechnology.

An immortalised cell line should not be confused with stem cells, which can also divide indefinitely, but form a normal part of the development of a multicellular organism.

Relation to natural biology and pathology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

There are various immortal cell lines. Some of them are normal cell lines (e.g. derived from stem cells). Other immortalised cell lines are the in vitro equivalent of cancerous cells. Cancer occurs when a somatic cell that normally cannot divide undergoes mutations that cause deregulation of the normal cell cycle controls, leading to uncontrolled proliferation. Immortalised cell lines have undergone similar mutations, allowing a cell type that would normally not be able to divide to be proliferated in vitro. The origins of some immortal cell lines – for example, HeLa human cells – are from naturally occurring cancers. HeLa, the first immortal human cell line on record to be successfully isolated and proliferated by a laboratory, was taken from Henrietta Lacks in 1951 at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.[1]

Role and uses

[edit]Immortalised cell lines are widely used as a simple model for more complex biological systems – for example, for the analysis of the biochemistry and cell biology of mammalian (including human) cells.[2] The main advantage of using an immortal cell line for research is its immortality; the cells can be grown indefinitely in culture. This simplifies analysis of the biology of cells that may otherwise have a limited lifetime.[citation needed]

Immortalised cell lines can also be cloned, giving rise to a clonal population that can, in turn, be propagated indefinitely. This allows an analysis to be repeated many times on genetically identical cells, which is desirable for repeatable scientific experiments. The alternative, performing an analysis on primary cells from multiple tissue donors, does not have this advantage.[citation needed]

Immortalised cell lines find use in biotechnology, where they are a cost-effective way of growing cells similar to those found in a multicellular organism in vitro. The cells are used for a wide variety of purposes, from testing toxicity of compounds or drugs to production of eukaryotic proteins.[citation needed]

Limitations

[edit]Changes from nonimmortal origins

[edit]While immortalised cell lines often originate from a well-known tissue type, they have undergone significant mutations to become immortal. This can alter the biology of the cell and must be taken into consideration in any analysis. Further, cell lines can change genetically over multiple passages, leading to phenotypic differences among isolates and potentially different experimental results depending on when and with what strain isolate an experiment is conducted.[3]

Contamination with other cells

[edit]Many cell lines that are widely used for biomedical research have been contaminated and overgrown by other, more aggressive cells. For example, supposed thyroid lines were actually melanoma cells, supposed prostate tissue was actually bladder cancer, and supposed normal uterine cultures were actually breast cancer.[4]

Methods of generation

[edit]There are several methods for generating immortalised cell lines:[5]

- Isolation from a naturally occurring cancer. This is the original method for generating an immortalised cell line. A major example is human HeLa, a line derived from cervical cancer cells taken on February 8, 1951 from Henrietta Lacks, a 31-year-old African-American mother of five, who died of cancer on October 4, 1951.[6]

- Introduction of a viral gene that partially deregulates the cell cycle (e.g., the adenovirus type 5 E1 gene was used to immortalise the HEK 293 cell line; the Epstein–Barr virus can immortalise B lymphocytes by infection[7]).

- Artificial expression of key proteins required for immortality, for example telomerase which prevents degradation of chromosome ends during DNA replication in eukaryotes.[8]

- Hybridoma technology, specifically used for generating immortalised antibody-producing B cell lines, where an antibody-producing B cell is fused with a myeloma (B cell cancer) cell.[9]

Examples

[edit]There are several examples of immortalised cell lines, each with different properties. Most immortalised cell lines are classified by the cell type they originated from or are most similar to biologically

- 3T3 cells – a mouse fibroblast cell line derived from a spontaneous mutation in cultured mouse embryo tissue.

- A549 cells – derived from a cancer patient lung tumor

- HeLa cells – a widely used human cell line isolated from cervical cancer patient Henrietta Lacks

- HEK 293 cells – derived from human fetal cells

- Huh7 cells – hepatocyte-derived carcinoma cell line

- Jurkat cells – a human T lymphocyte cell line isolated from a case of leukemia

- OK cells – derived from female North American opossum kidney cells

- Ptk2 cells – derived from male long-nosed potoroo epithelial kidney cells

- Vero cells – a monkey kidney cell line that arose by spontaneous immortalisation

See also

[edit]- Cellosaurus, knowledge base of cell lines

- IGRhCellID, database of cell lines

- List of breast cancer cell lines

References

[edit]- ^ Skloot R (2010). Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-71253-0. OCLC 974000732. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Kaur G, Dufour JM (January 2012). "Cell lines: Valuable tools or useless artifacts". Spermatogenesis. 2 (1): 1–5. doi:10.4161/spmg.19885. PMC 3341241. PMID 22553484.

- ^ Marx V (April 2014). "Cell-line authentication demystified". Technology Feature. Nature Methods (Paper "Nature Reprint Collection, Technology Features" (Nov 2014)). 11 (5): 483–8. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2932. PMID 24781320. S2CID 205422738.

- ^ Neimark J (February 2015). "Line of attack". Science. 347 (6225): 938–40. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..938N. doi:10.1126/science.347.6225.938. PMID 25722392.

- ^ Maqsood MI, Matin MM, Bahrami AR, Ghasroldasht MM (October 2013). "Immortality of cell lines: challenges and advantages of establishment". Cell Biology International. 37 (10): 1038–45. doi:10.1002/cbin.10137. PMID 23723166. S2CID 14777249.

- ^ Skloot, Rebecca. "Henrietta's Dance". Johns Hopkins Magazine. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Henle W, Henle G (1980). "Epidemiologic aspects of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated diseases". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 354: 326–31. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27975.x. PMID 6261650. S2CID 30025994.

- ^ Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, et al. (January 1998). "Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells". Science. 279 (5349): 349–52. Bibcode:1998Sci...279..349B. doi:10.1126/science.279.5349.349. PMID 9454332.

- ^ Kwakkenbos MJ, van Helden PM, Beaumont T, Spits H (March 2016). "Stable long-term cultures of self-renewing B cells and their applications". Immunological Reviews. 270 (1): 65–77. doi:10.1111/imr.12395. PMC 4755196. PMID 26864105.

External links

[edit]Immortalised cell line

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamental Properties

Biological Mechanisms Enabling Immortality

Immortalized cell lines evade the finite replicative lifespan of primary cells, which is primarily governed by telomere attrition and activation of senescence checkpoints. In normal somatic cells, progressive telomere shortening during DNA replication triggers a DNA damage response, leading to replicative senescence mediated by the p53-p21 and Rb-p16 pathways; p53 induces cell cycle arrest via p21 upregulation, while Rb enforces G1/S restriction through interaction with E2F transcription factors.[6][7] Without intervention, cells undergo approximately 50-70 divisions before senescence, as observed in human fibroblasts.[8] Achievement of immortality requires inactivation of these anti-proliferative barriers, often through genetic alterations targeting the p53 and Rb pathways. Mutations or loss of p53 function, occurring in over 50% of human cancers, prevent downstream senescence signaling, allowing continued proliferation despite telomere erosion; similarly, Rb pathway disruption—via mutations in Rb itself, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors like p16^INK4a, or viral oncoproteins such as SV40 large T antigen—releases E2F-mediated transcription of S-phase genes.[9][10] In experimental immortalization, co-introduction of dominant-negative p53 mutants or Rb-binding proteins extends lifespan but typically induces a secondary "crisis" phase characterized by genomic instability unless telomere maintenance is activated.[11] These alterations are necessary but insufficient alone, as evidenced by studies showing that p53/Rb-deficient cells still senesce without telomere stabilization.[12] Telomere maintenance mechanisms ultimately confer indefinite replication by countering attrition. The predominant pathway involves reactivation of telomerase, a ribonucleoprotein enzyme comprising the catalytic subunit hTERT and RNA component hTERC, which adds TTAGGG repeats to chromosome ends; hTERT upregulation, absent in most somatic cells but present in 85-90% of immortalized lines and tumors, restores telomere length and prevents crisis.[8] Alternatively, 10-15% of cases employ ALT, a recombination-dependent process involving break-induced replication and telomere clustering in PML bodies, leading to heterogeneous telomere lengths without telomerase activity; ALT is characterized by C-circles (extrachromosomal telomeric DNA) and is prevalent in sarcomas and certain cell lines.[13][14] In engineered lines, direct hTERT transduction combined with p53/Rb inactivation yields stable immortality, mimicking cancer-derived mechanisms while minimizing gross genomic changes.[15] These processes ensure causal decoupling from Hayflick limits, enabling billions of divisions in culture.[16]Distinctions from Finite Lifespan Cells and Primary Cultures

Immortalised cell lines differ fundamentally from finite lifespan cells and primary cultures in their capacity for indefinite proliferation, bypassing the replicative senescence imposed by telomere attrition. Finite lifespan cells, such as diploid fibroblasts derived from normal tissues, adhere to the Hayflick limit, undergoing approximately 50-60 population doublings before entering senescence due to progressive telomere shortening during DNA replication.[17][18] Primary cultures, isolated directly from donor tissues with minimal manipulation, exhibit similar finite division potential and retain physiological characteristics closer to in vivo states, but they require specialized media and growth factors to mimic native microenvironments.[19] In contrast, immortalised lines evade this limit through mechanisms like telomerase reactivation or inactivation of tumor suppressor pathways, enabling unlimited divisions without senescence.[20]| Aspect | Finite Lifespan Cells and Primary Cultures | Immortalised Cell Lines |

|---|---|---|

| Proliferative Capacity | Limited to ~30-60 doublings; senescence triggered by telomere erosion and DNA damage accumulation.[17][18] | Indefinite; bypass senescence via telomerase or oncogenic alterations.[20][1] |

| Genetic Stability | Typically diploid with stable karyotypes; minimal mutations during culture.[19] | Often aneuploid with chromosomal aberrations and accumulated mutations from prolonged passaging.[2][22] |

| Phenotypic Fidelity | Preserve differentiation and in vivo-like responses; heterogeneous but biologically relevant.[19][2] | May dedifferentiate, alter gene expression (e.g., upregulated proliferation genes), and diverge from primary counterparts.[22][2] |

| Culture Requirements | Complex; need serum-free or supplemented media, extracellular matrices, and short-term viability.[23] | Simpler; thrive in standard media with fetal bovine serum, enabling scalability and consistency.[23][19] |

Historical Development

Early Animal and Pre-Human Milestones

In the early 20th century, pioneering work in cell culture laid foundational milestones for achieving indefinite propagation, initially with non-mammalian animal tissues. In 1907, Ross Granville Harrison established the first sustained animal cell cultures using nerve fibers from frog embryos (Rana sp.), demonstrating that cells could survive and extend processes in vitro for weeks, though these primary cultures exhibited finite lifespans limited by senescence and lacked serial subculturing capability.[24] This amphibian model advanced techniques for observing cellular outgrowth but did not yield immortalized lines, as cells ceased division without transformation.[24] A significant avian milestone occurred in 1912 when Alexis Carrel, working at the Rockefeller Institute, explanted cardiac muscle tissue from a chicken embryo heart and maintained it through serial transfers, claiming perpetual growth over decades without senescence.[25] Carrel's perfusion-based methods, involving nutrient renewal and removal of waste, enabled over 3,000 subcultures by 1946, interpreted at the time as evidence of intrinsic cellular immortality.[24] However, retrospective analyses in the 1960s revealed that sustained growth relied on selective propagation of peripheral, faster-dividing cells—effectively enriching for spontaneous mutants—rather than true immortality of the original population, as unselected cultures senesced normally.[26] Despite this caveat, Carrel's chick heart strain represented an early approximation of continuous culture, influencing subsequent mammalian efforts by proving long-term viability through meticulous technique.[24] Mammalian immortalization advanced in the 1940s with the establishment of the first continuous rodent cell line. In 1943, Wilton R. Earle at the National Cancer Institute derived Strain L (later cloned as L929 in 1948) from subcutaneous areolar and adipose tissue of a C3H mouse, achieving indefinite serial propagation after initial adaptation in plasma clots and roller tubes.[27] These fibroblastoid cells, propagated over thousands of generations, overcame contact inhibition and density-dependent growth arrest through unknown spontaneous genetic alterations, marking the inaugural stable mammalian line predating human examples. Earle's L cells enabled clonal isolation and mass culture, facilitating virology and oncology studies, though their derivation from non-tumor tissue highlighted that immortalization could arise via adaptive selection rather than explicit oncogenic transformation.[28] This pre-1950 achievement underscored the feasibility of perpetual animal cell lines, bridging exploratory avian work to scalable mammalian models.[27]The HeLa Breakthrough and Initial Human Lines (1950s)

In February 1951, George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins Hospital, obtained a biopsy sample from a cervical tumor of Henrietta Lacks, a 31-year-old African-American woman undergoing treatment for adenocarcinoma.[4] Unlike prior attempts to culture human cells, which typically senesced after a limited number of divisions, Lacks' tumor cells exhibited indefinite proliferation in vitro, doubling approximately every 24 hours under standard nutrient conditions.[29] Gey, along with his wife Margaret and technician Mary Kubicek, designated the line "HeLa," derived from the first two letters of Lacks' first and last names, marking the first established immortalized human cell line.[4][30] The HeLa line's robustness stemmed from its derivation from aggressive cancer cells harboring high telomerase activity and chromosomal abnormalities, enabling evasion of replicative senescence—a phenomenon not replicated in normal human tissues cultured previously.[31] By 1952, HeLa cells were distributed to laboratories worldwide, facilitating viral propagation studies critical for vaccine development, including Jonas Salk's poliovirus trials where HeLa served as a substrate for virus growth and titration.[3] This breakthrough shifted cell culture from reliance on animal models, such as mouse fibroblasts, to human-specific systems, though early distributions occurred without Lacks' informed consent, as tissue sampling was routine medical practice at the time without ethical oversight for research use.[32] In 1953, Theodore Puck and Philip Marcus achieved the first cloning of human cells using HeLa, isolating single cells via micromanipulation and demonstrating their capacity for colony formation, which validated the line's genetic stability and purity for experimental reproducibility.[29] While HeLa dominated 1950s human cell research due to its availability and vigor, subsequent efforts yielded limited additional lines, such as KB cells from a human epidermoid carcinoma in 1954, though many later proved contaminated with HeLa genetics, underscoring HeLa's pervasive influence and the technical challenges in establishing uncontaminated alternatives.[32] These initial human lines propelled cytogenetic, virological, and pharmacological investigations, laying groundwork for modern biomedical assays despite the era's rudimentary sterility and authentication protocols.[3]Methods of Generation

Spontaneous and Cancer-Derived Immortalization

Spontaneous immortalization refers to the rare acquisition of indefinite proliferative capacity by non-transformed primary cells during extended culture, without deliberate genetic or viral intervention. This process typically arises after cells exhaust their replicative lifespan due to telomere shortening, enter replicative senescence, and then overcome a subsequent "crisis" phase characterized by widespread cell death. Surviving clones emerge with mechanisms to maintain telomeres, such as activation of alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) or rare telomerase upregulation, alongside chromosomal instability and epigenetic alterations. In human cells, the frequency of spontaneous immortalization from cultures in crisis is approximately 10^{-7} to 10^{-5}, reflecting stringent anti-cancer safeguards like p53-mediated apoptosis.[33] Rodent cells immortalize more readily, with probabilities inversely correlated to species body mass, suggesting evolutionary pressures against uncontrolled proliferation in larger organisms.[34] Mechanistically, spontaneous immortalization involves cumulative genetic hits, including aneuuploidy and rearrangements that bypass senescence pathways, but these lines often retain contact inhibition and fail to form tumors in vivo, distinguishing them from fully transformed cells. For instance, spontaneously immortalized chicken fibroblasts exhibit stable karyotypes post-immortalization via epigenetic reprogramming during serial passaging.[35] Similarly, human dermal microvascular endothelial cells have been isolated through spontaneous events, enabling organ-specific lines without oncogenic transgenes.[36] Such lines provide models closer to normal physiology than engineered ones, though their rarity limits routine use; immortalization probability declines with higher organismal complexity, as seen in mammalian systems where it requires overriding multiple tumor suppressor networks.[6] Cancer-derived immortalization, by contrast, exploits pre-existing oncogenic mutations in tumor biopsies, yielding lines that proliferate indefinitely due to inherent evasion of senescence and apoptosis. These cells typically harbor activated telomerase (in ~90% of human cancers), disrupted Rb/p53 pathways, and aneuploid genomes, hallmarks enabling replicative immortality as a cancer enabler. Derived via explant culture from resected tumors, examples include HeLa cells from a 1951 cervical adenocarcinoma biopsy, which retain human papillomavirus oncogenes E6/E7 driving proliferation.[37] Other lines, like those from breast or lung carcinomas, display heterogeneous antigenic profiles despite single-tumor origins, reflecting intratumoral diversity.[38] Unlike spontaneous events, cancer lines are tumorigenic, anchorage-independent, and genomically unstable, often diverging further in vitro from primary tumors through selection for fast growth. Primary cancer cultures from surgeries provide starting material, but serial passaging selects immortal subclones amid fibroblast overgrowth.[39] This method dominates immortal line generation—over 1,000 human lines span 27 cancer types—facilitating gene expression studies but risking artifacts from long-term adaptation.[40] Critically, while spontaneous immortalization mimics rare in vivo escape from senescence without full transformation, cancer-derived lines embody pathological immortality, prioritizing high-throughput utility over physiological fidelity.[41]Viral and Oncogenic Transformation

Viral transformation of primary cells into immortalized lines relies on oncogenic viruses that express proteins disrupting key cellular checkpoints governing senescence and apoptosis. These viruses, including Simian Virus 40 (SV40), Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), Human Papillomavirus (HPV), and Adenovirus, encode oncoproteins that inactivate tumor suppressors such as p53 and retinoblastoma protein (pRb), thereby extending replicative lifespan and enabling indefinite proliferation in vitro.[42][43] This process often involves two phases: initial extension of the Hayflick limit followed by escape from replicative crisis, where surviving cells acquire chromosomal abnormalities but gain immortality.[44] SV40, isolated from rhesus monkey kidney cells in 1960, exemplifies viral immortalization through its large T antigen, which binds p53 to prevent DNA damage-induced arrest and sequesters pRb to promote cell cycle progression via E2F release.[44][45] Transfection or infection with SV40 DNA or the T antigen gene has successfully immortalized human fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and mesenchymal cells, though human cells frequently undergo a prolonged crisis phase with high apoptosis rates before rare immortal clones emerge.[46] This method's efficiency varies by cell type, achieving rates up to 10^-5 for rodent fibroblasts but lower for human lines, and it often confers additional transformed phenotypes like anchorage-independent growth.[47] EBV, a herpesvirus associated with Burkitt's lymphoma, specifically targets human B lymphocytes for transformation into lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs), with efficiencies approaching 100% in peripheral blood mononuclear cells under optimal conditions.[48] Immortalization requires EBV's latent genes, including EBV nuclear antigens (EBNA-1 to -6) and latent membrane proteins (LMP-1, LMP-2), which mimic B-cell receptor signaling, activate NF-κB pathways, and upregulate telomerase to counteract telomere shortening.[49][50] Established in the 1960s, EBV-LCLs proliferate indefinitely without crisis but retain some lymphoid characteristics, making them valuable for immunological studies despite potential viral latency risks.[51] Other viruses contribute to targeted immortalization: HPV-16/18 E6 oncoprotein ubiquitinates p53 for degradation, while E7 binds pRb, enabling epithelial cell lines like those from keratinocytes or cervical tissue, with transformation efficiencies improved by co-expression.[42] Adenovirus type 5 E1A and E1B genes, used in HEK293 cells since 1977, similarly abrogate p53 and pRb functions, supporting high-level recombinant protein production.[20] Oncogenic transformation extends beyond intact viruses to direct genetic delivery of oncogenes, often via plasmids or retroviruses, to mimic viral effects without full viral lifecycle. For instance, co-transfection of activated H-ras and simian virus large T antigen (non-viral context) or c-myc overexpression inactivates senescence pathways, yielding transformed lines from fibroblasts or T cells, though requiring additional hits like p16^INK4a suppression for stable immortality.[52][53] Chemical carcinogens, such as 3-methylcholanthrene, induce oncogenic mutations leading to spontaneous transformation in rodent cells, but human applications are rare due to inefficiency and ethical concerns over tumorigenicity.[20] These methods confer not only immortality but also hallmarks of malignancy, including genomic instability, distinguishing them from non-transformed immortal lines; however, they risk unintended oncogenic potential in vivo.[53][54]Telomerase and Genetic Engineering Approaches

One approach to generating immortalized cell lines involves ectopic expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase, human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), which restores telomere maintenance in primary cells lacking endogenous activity.[20] In normal human somatic cells, telomere attrition after approximately 50-70 divisions triggers replicative senescence via the Hayflick limit, but hTERT transfection—typically via plasmid, lentiviral, or retroviral vectors—activates telomerase to elongate telomeres, enabling indefinite proliferation without the chromosomal instability often seen in cancer-derived lines.[42] This method was first successfully applied to primary human cells in 1998, immortalizing fibroblasts, retinal epithelial cells, and vascular endothelial cells while retaining key differentiated functions and near-normal karyotypes.[55] hTERT immortalization preserves phenotypic fidelity better than viral oncogenic transformations, as it targets only the telomere clock without broadly disrupting tumor suppressor pathways like p53 or Rb, though some cell types require co-expression of additional factors such as Bmi-1 to fully bypass alternative senescence mechanisms.[20] For instance, lentiviral transduction of hTERT into human adipose-derived stem cells or myometrial cells has yielded lines with extended lifespans exceeding 200 population doublings, maintaining hormone responsiveness and minimal aneuploidy.[56][57] Delivery methods include electroporation or lipofection of hTERT plasmids for non-integrating approaches, reducing insertional mutagenesis risks, though efficiency varies by cell type and often necessitates selection with antibiotics like puromycin.[58] Beyond telomerase, non-viral genetic engineering employs direct plasmid transfection or CRISPR-Cas9 editing to introduce or activate genes modulating senescence, such as CDK4 mutants to inhibit p16/Rb arrest or dominant-negative p53 variants.[20] These techniques, often combined with hTERT, have immortalized mesenchymal stromal cells and podocytes, achieving proliferation rates 5-10 times higher than primaries without full oncogenic conversion.[59] However, success rates remain cell-type dependent; epithelial cells may require sequential modifications to overcome multiple crisis barriers, and engineered lines must be rigorously authenticated for off-target edits via karyotyping and telomere length assays.[60] Conditional systems, using inducible promoters for hTERT or immortalizing transgenes, further enhance control, allowing reversible immortality in research models.[61]Key Examples

HeLa Cells: Origins and Ubiquity

HeLa cells originated from a biopsy of a cervical adenocarcinoma tumor taken from Henrietta Lacks, a 31-year-old African American woman, during her treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital in February 1951.[62][63] Dr. George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at the institution, isolated the cells from the sample, which unexpectedly demonstrated the ability to proliferate indefinitely in culture, marking the first successful establishment of an immortalized human cell line.[4][29] The line was named "HeLa" using the first two letters of Lacks' surname and given name, and its robustness allowed for easy subculturing and distribution among laboratories without commercialization by Johns Hopkins.[4] By 1952, HeLa cells had been confirmed as capable of endless division, enabling their widespread adoption as a model for human cellular research.[3] Their ubiquity stems from this pioneering immortality, which facilitated breakthroughs such as the development of the Salk polio vaccine through virus propagation and the study of cellular responses to radiation, viruses, and environmental factors like zero gravity.[4] HeLa has become the most commonly used human cell line globally, appearing in research on diverse diseases and fundamental biological processes, with publication usage peaking at approximately 6,200 papers in 2015 and showing consistent growth thereafter.[64][65] Despite occasional issues like genetic variability from prolonged passaging, HeLa's reliability and availability have cemented its status as a cornerstone of biomedical science, referenced in tens of thousands of studies worldwide.[66][67]Other Human and Animal Lines (e.g., Vero, CHO)

Vero cells, derived from the kidney epithelial tissue of an African green monkey (Chlorocebus sabaeus), represent a spontaneously immortalized line established in 1962 by Yasuo Yasumura and colleagues at Chiba University, Japan.[68] This line lacks functional p53 and Rb tumor suppressor genes, contributing to its indefinite proliferation, and has been widely adapted into sublines such as Vero E6 for enhanced viral susceptibility.[68] Vero cells are extensively employed in virology for isolating and propagating viruses, including poliovirus, rabies virus, and Ebola virus, due to their permissiveness for viral replication without productive infection in many cases.[69] They have served as substrates for vaccine production, notably in inactivated polio vaccines and certain SARS-CoV-2 vaccines like Sinovac.[70] Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, originating from the ovary of a female Chinese hamster (Cricetulus griseus) in 1957, were isolated and immortalized by Theodore Puck's laboratory through selective culturing of epithelial-like cells.[71] These cells exhibit robust growth in suspension, efficient genetic manipulation, and human-like post-translational modifications, making them the dominant platform for industrial-scale recombinant protein production, accounting for over 70% of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies approved by regulatory agencies as of 2020.[72] Variants like CHO-K1 and CHO-DG44, engineered for dihydrofolate reductase deficiency to facilitate gene amplification, support high-yield expression of biologics such as erythropoietin and etanercept.[72] Their use minimizes risks of human viral contamination compared to human lines, enhancing safety in biomanufacturing.[73] Among other human immortalized lines, HEK293 cells, generated in 1973 by Alex van der Eb and Frank Graham through transformation of human embryonic kidney cells with sheared adenovirus type 5 DNA, are prized for high transfection efficiency via calcium phosphate methods and expression of viral E1A/E1B genes that drive proliferation.[74] These cells support transient and stable production of recombinant proteins, viral vectors for gene therapy, and pharmacological screening, with subline HEK293T incorporating SV40 large T antigen for further enhanced replication.[74] Jurkat cells, established in 1976 from a human T-cell leukemia, provide a model for immune signaling and apoptosis studies due to their constitutive IL-2 independence and responsiveness to T-cell receptor stimulation.[75] Additional animal lines include Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, derived from a cocker spaniel kidney in 1958 and spontaneously immortalized, which form polarized epithelia mimicking renal tubules and are used for influenza virus propagation and vaccine substrate, as in Flucelvax.[1] These lines collectively enable scalable, reproducible experiments but require authentication to mitigate cross-contamination risks prevalent in cell culture repositories.[76]Applications in Research and Industry

Modeling Disease and Basic Cellular Processes

Immortalized cell lines enable the modeling of disease states by providing a stable, renewable source of cells that mimic aspects of pathological conditions, allowing researchers to investigate disease mechanisms without the constraints of finite primary cell lifespans. These lines facilitate long-term studies of cellular responses to genetic mutations, environmental stressors, and therapeutic interventions, as their indefinite proliferation supports high-throughput assays and repeated experimentation under controlled conditions. For example, cancer-derived lines like HeLa replicate tumor cell behaviors such as uncontrolled growth and invasiveness, aiding in the dissection of oncogenic pathways.[77][78] Specific applications in disease modeling include the use of HeLa cells to study cervical cancer progression linked to human papillomavirus infection, where they have revealed insights into viral integration and host cell transformation since their establishment in 1951. Immortalized lines from patient tumors, such as the spontaneously derived myxofibrosarcoma line MF-R 3 established in 2023, preserve tumor-specific genetic profiles for testing targeted therapies and metastasis dynamics. In neurodegenerative research, immortalized neuronal lines model protein aggregation in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, enabling evaluation of proteotoxic stress and neuroprotective strategies. Non-human primate immortalized kidney cells, developed in 2023, replicate viral replication cycles for pathogens like Ebola and Zika, supporting pathogenesis studies unattainable with primary cells due to ethical and availability limits.[78][79][80][81] For basic cellular processes, immortalized lines serve as platforms to probe fundamental mechanisms like cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and signal transduction, decoupled from organismal influences. They allow precise manipulation via genetic engineering to isolate variables, such as telomerase overexpression in hTERT-immortalized fibroblasts, which elucidates replicative senescence evasion and telomere maintenance roles in aging. These models have advanced understanding of apoptosis regulation and metabolic reprogramming, with lines like NIH3T3 used to dissect fibroblast transformation and oncogenic signaling cascades. By standardizing experimental conditions, immortalized cells yield reproducible data on intracellular dynamics, underpinning discoveries in cellular homeostasis and response to perturbations.[20][82][83]Drug Screening and Toxicity Testing

Immortalized cell lines enable high-throughput screening of compound libraries in pharmaceutical development by providing a renewable, genetically stable population for repeated assays, reducing reliance on finite primary cells.[84] These lines support phenotypic and target-based screens, such as measuring cell proliferation, apoptosis, or reporter gene expression following compound exposure, facilitating the identification of hits with desired pharmacological activity.[85] In practice, lines like HEK293, engineered for transient transfection, are routinely used to express recombinant targets such as G-protein coupled receptors or ion channels, allowing quantification of agonist/antagonist effects via fluorescence or luminescence readouts.[86] Cancer-derived immortalized lines, including HeLa and various adenocarcinoma models, are staples for anti-neoplastic drug screening, where metrics like IC50 values for growth inhibition are derived from dose-response curves in 96- or 384-well formats.[87] For instance, high-throughput platforms employing these cells have accelerated the discovery of kinase inhibitors by integrating genomic profiling with functional assays, though results require validation due to line-specific genetic heterogeneity.[87] Similarly, CHO cells, immortalized via dihydrofolate reductase selection, underpin screens for biologics production and efficacy, leveraging their robustness for large-scale automation.[84] In toxicity testing, immortalized lines assess compound-induced cytotoxicity through endpoints like MTT reduction, LDH release, or ATP content, serving as initial filters to predict acute organ toxicities before in vivo studies.[88] Organ-specific examples include HepG2 hepatocytes for hepatic metabolism and steatosis evaluation, HK-2 proximal tubule cells for nephrotoxicity via biomarkers like KIM-1 expression, and A549 lung epithelial cells for pulmonary irritancy.[89][90] These models demonstrate moderate concordance with rodent data—approximately 60-70% sensitivity for general cytotoxicity—but underperform for chronic or idiosyncratic toxicities due to absent tissue architecture and immune interactions.[91] Despite their utility, the oncogenic alterations inherent to many immortalized lines, such as p53 inactivation or telomerase overexpression, can artifactually diminish sensitivity to genotoxicants or apoptotic inducers, leading to underestimation of risks observed in primary tissues or animals.[92] Consequently, regulatory frameworks like FDA guidelines recommend tiered testing, with 2D immortalized cultures triaging candidates for advancement to 3D spheroids or animal models to enhance translational accuracy.[93] This approach mitigates false negatives while acknowledging that no single in vitro system fully replicates systemic pharmacokinetics or multi-organ effects.[94]Biomanufacturing and Vaccine Production

Immortalized cell lines facilitate large-scale biomanufacturing of biologics and vaccines by enabling indefinite proliferation, high-density suspension cultures, and consistent product yields in serum-free media, which primary cells cannot sustain.[95] These properties allow for scalable bioreactor processes reaching thousands of liters, reducing costs and variability compared to finite cell sources.[96] Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, derived from spontaneous immortalization in the 1950s, dominate recombinant protein production, accounting for over 70% of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) approved for therapeutic use.[97] Engineered CHO lines achieve mAb titers exceeding 4 g/L through optimized metabolic pathways and gene amplification, supporting annual global outputs in the hundreds of tons for drugs like rituximab and trastuzumab.[98] Their robustness in fed-batch or perfusion cultures minimizes phenotypic drift under industrial stress, though genetic instability requires clonal selection for each product.[99] In vaccine production, Vero cells—African green monkey kidney cells immortalized by SV40 virus in 1962—serve as a WHO-approved substrate for virus propagation due to high susceptibility to diverse pathogens and yields up to 10^9 plaque-forming units per mL.[100] Examples include inactivated polio vaccine (IPOL, licensed 1987), rabies vaccine (Imovax, 1981), rotavirus vaccine (Rotateq, 2006), and Sinopharm's SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (2020), where Vero monolayers or suspensions support both inactivated and live-attenuated formats without adventitious agent risks after rigorous banking.[101] [102] Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells, transformed by adenovirus type 5 in 1973, enable production of viral vectors and subunit vaccines, yielding up to 10^10 infectious virions per mL for influenza or adenoviral platforms like those in some COVID-19 candidates.[103] Their human glycosylation machinery improves immunogenicity over non-human lines, though ethical sourcing concerns limit adoption compared to animal-derived alternatives.[104] Emerging CHO adaptations for viral vaccines further expand immortalized lines' role, promising integrated platforms for next-generation biologics.[105]Scientific Limitations and Risks

Genetic Instability and Phenotypic Drift

Immortalized cell lines commonly display chromosomal instability (CIN), manifesting as aneuploidy, structural aberrations, and elevated mutation rates that generate intra-population genetic heterogeneity.[106] This instability stems from immortalization mechanisms—such as viral oncogene integration or telomerase activation—that disrupt normal genomic safeguards, compounded by selective pressures in culture favoring rapid proliferation over fidelity.[107] In HeLa cells, derived from cervical carcinoma in 1951, the karyotype exhibits hyper-triploidy with 76–80 chromosomes per cell and 22–25 abnormal chromosomes, including widespread rearrangements across at least 20 chromosomes.[108][109] Such aberrations accumulate progressively; for instance, HeLa sublines passaged extensively show increased frequencies of chromosomal breaks and exchanges, rising from 6.9% to 29.7% aberrant cells compared to low-passage counterparts.[110] CIN drives ongoing evolution within cultures, as mutagenic events outpace repair, leading to divergent subclones that compete under nutrient-limited or stressed conditions.[111] Aneuploidy, a hallmark outcome of CIN, further amplifies proteome imbalances and proteotoxic stress, perpetuating a cycle of instability rather than stable immortality.[111] In pharmacogenomic analyses of cancer cell lines, genetic drift—defined as cumulative structural variants—affects 4.5–6.1% of the genome between ostensibly isogenic strains, confounding heritability of traits like drug sensitivity.[112] Phenotypic drift arises as a downstream consequence, where genetically variant subclones outcompete originals, shifting observable traits such as morphology, proliferation rates, and gene expression profiles over serial passages.[106] In Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells used for biomanufacturing, extended culturing (beyond 60–100 passages) induces morphological alterations, reduced productivity, and functional divergences, including altered metabolism and adhesion properties.[113] Karyotypic instability exacerbates this; cancer lines with unstable genomes yield inconsistent phenotypes across labs, with passage-dependent variations undermining reproducibility in assays.[114] High passage numbers amplify drift, as continuous subculturing selects for adaptations irrelevant to native tissue, such as anchorage independence or altered signaling, decoupling lines from their originating biology.[115][116] These dynamics pose risks for research validity, as drifted lines may yield non-representative data on cellular processes or drug responses, necessitating vigilant monitoring of passage history and genomic integrity.[115] While short-term cultures mitigate drift, the inherent mutability of immortalization precludes long-term fidelity, highlighting a fundamental limitation in using such lines for precise modeling.[106]Contamination and Authentication Challenges

Cross-contamination between cell lines, particularly by fast-growing immortalized lines like HeLa, has plagued cell culture research since the 1950s, with HeLa cells—derived from Henrietta Lacks' cervical cancer biopsy in 1951—frequently overtaking and replacing other cultures due to their aggressive proliferation.[117][118] By the 1970s, researchers including Walter Nelson-Rees identified widespread HeLa infiltration in purportedly distinct lines, prompting warnings that were often ignored, leading to contaminated studies persisting into the 1980s and beyond.[119] This issue extends beyond HeLa; estimates indicate 15–20% of cell lines in biomedical research are misidentified or cross-contaminated, with some surveys reporting rates up to 30–50% for certain collections, resulting in billions of dollars in wasted resources and irreproducible findings.[120][121][122] Microbial contamination compounds these problems, with mycoplasma infecting up to 30% of cultures in some labs due to undetected airborne or reagent transmission, altering cellular metabolism, gene expression, and drug responses without overt signs.[123] Viral contaminants, including retroviruses from xenograft passaging, affect 3–5% of human lines, while bacteria and fungi cause rapid culture failure if not sterile.[124] Immortalized lines' indefinite propagation amplifies risks, as genetic drift and selection for contaminants evade early detection, undermining data reliability.[125] Authentication challenges arise from inconsistent adoption of verification methods, despite standards like short tandem repeat (STR) profiling, which generates DNA fingerprints matching against databases for human lines with >80% allele concordance confirming identity.[126][127] The International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC), established to curate misidentified line registries, lists over 500 problematic entries, yet many researchers skip routine checks due to cost, expertise gaps, or over-reliance on supplier claims, perpetuating errors.[128][129] Peer-reviewed journals now mandate authentication for publications, but historical lapses mean contaminated lines propagate via shared stocks, with intra-species mislabeling (e.g., 85% in some Chinese-origin collections) evading morphology-based checks.[130][131] Effective mitigation requires periodic STR re-verification, mycoplasma screening via PCR, and ICLAC database consultation, though incomplete global enforcement hinders progress.[132][133]Inaccuracies in Representing Native Tissue Biology

Immortalized cell lines, derived through oncogenic transformation or viral immortalization, often fail to maintain the physiological fidelity of primary cells from native tissues due to adaptive changes during establishment and propagation in vitro. These lines undergo genetic and epigenetic alterations that diverge from the original tissue's cellular heterogeneity and functional architecture, leading to discrepancies in gene expression profiles and metabolic pathways. For instance, proteomic analyses of immortalized hepatocyte lines like Hepa1-6 reveal significantly downregulated proteins compared to primary hepatocytes, undermining their utility in modeling liver-specific functions.[134] A primary inaccuracy stems from the homogeneous clonal expansion of immortalized lines, which contrasts with the diverse, heterogeneous cell populations in native tissues that include multiple subtypes interacting dynamically. Unlike primary cells isolated directly from tissues, which preserve intercellular signaling and extracellular matrix dependencies, immortalized lines adapt to artificial 2D monolayers, losing tissue-specific polarity, adhesion complexes, and 3D structural cues essential for authentic physiology. Tumor-derived lines, such as many human cancer cell lines, further exacerbate this by exhibiting dedifferentiation and aberrant proliferation not reflective of normal tissue homeostasis.[135][136][23] Phenotypic drift compounds these issues, as prolonged passaging induces progressive divergence from native states through accumulated mutations and selective pressures in culture media. This drift manifests in altered drug responses and signaling cascades; for example, immortalized lines frequently overestimate cellular resilience to stressors compared to in vivo tissues, contributing to high attrition rates in drug development pipelines where in vitro hits fail clinical translation. Studies highlight that such lines lack the senescence limits and microenvironmental feedbacks of primary cells, resulting in non-physiological immortality that skews interpretations of disease modeling and toxicity.[137][138][135] Moreover, immortalized lines inadequately recapitulate tissue-level interactions, such as immune cell infiltration or vascular integration, due to their isolation from systemic contexts. This limitation is evident in their reduced predictive power for organ-specific pathologies, where primary or organoid models better emulate native barriers and compartmentalization. Empirical evidence from comparative assays shows immortalized endothelial lines failing to sustain physiological shear stress responses akin to vascular tissues, underscoring the causal disconnect between monolayer artifacts and in vivo realism.[139][140][141]Ethical and Legal Controversies

Consent Violations and Historical Exploitation

The most prominent case of consent violation in the derivation of an immortalized human cell line involves Henrietta Lacks, from whose cervical tumor tissue the HeLa line was established in 1951 at Johns Hopkins Hospital. During treatment for aggressive cervical cancer, a biopsy sample was taken without Lacks' knowledge or permission for research purposes beyond her clinical care; she died from the disease on October 4, 1951, at age 31.[142][143][144] The cells, isolated by researcher George Gey, demonstrated indefinite replication in vitro—the first such human line—and were distributed globally without compensation or acknowledgment to Lacks or her family, reflecting standard practices of the era when no federal regulations mandated informed consent for secondary research use of excised tissues.[145][146] HeLa cells fueled pivotal advances, including the 1954 Salk polio vaccine development, HIV research, and cancer studies, generating an estimated economic value exceeding $100 billion through licensing and applications by pharmaceutical firms.[142] Yet Lacks' descendants, many living in poverty, received no financial benefits or control over the line's use until decades later; the family was not informed of the cells' origin until 1973, when a journalist investigating contaminated cultures revealed their identity.[147] This exploitation underscored disparities in mid-20th-century U.S. biomedical research, where tissues from indigent, African American patients like Lacks—a tobacco farmer from rural Virginia—were routinely appropriated amid broader patterns of unequal medical access and experimentation on vulnerable groups, absent the ethical frameworks later codified in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki or U.S. Common Rule.[66][145] Efforts at redress emerged piecemeal: In 2013, the National Institutes of Health negotiated a controlled-access agreement with Lacks' family for HeLa genomic sequencing data, granting them review roles on publications involving her cells' full genome.[145] More recently, in August 2023, the family settled a lawsuit against Thermo Fisher Scientific, accusing the company of unjust enrichment from profiting off HeLa-derived products without compensating the originators, though settlement terms remained confidential.[148][149] These developments highlight ongoing tensions between historical precedents—where consent was not legally required—and evolving standards prioritizing patient autonomy, though HeLa remains in widespread use without retroactive royalties.[150] While HeLa exemplifies consent lapses in immortalized lines, analogous issues have surfaced in other derivations, often involving marginalized donors in resource-limited settings. For instance, early efforts in African genomics research raised concerns over cell line creation from vulnerable communities without robust consent processes, perpetuating risks of exploitation akin to colonial-era biospecimen collection.[151] Such cases, though less documented for specific immortalized lines, illustrate how pre-1970s norms prioritized scientific utility over individual rights, prompting modern policies like the U.S. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects to mandate prospective informed consent for biospecimen research.[152]Commercialization Without Benefit Sharing

The commercialization of immortalized cell lines, particularly the HeLa line derived from Henrietta Lacks's cervical tumor cells harvested on February 8, 1951, has exemplified the absence of benefit sharing with originating donors or their descendants.[153] Following their identification as the first stable human cell line capable of indefinite proliferation, HeLa cells were distributed without restriction by Johns Hopkins University, which explicitly states it never patented or profited from them, providing vials freely to researchers.[154] However, biotechnology firms subsequently commercialized HeLa-derived products, including cell vials sold for research at prices up to $861 each and applications in drug testing, vaccine production, and gene therapy vectors, contributing to a broader immortalized cell line market valued at approximately USD 4.87 billion in 2024.[155][156] This commercialization occurred without compensating Lacks's family, who remained in poverty and faced medical debt for decades despite the cells' role in breakthroughs like the polio vaccine and HPV vaccine development.[157] Companies such as Thermo Fisher Scientific profited from selling HeLa cells and related reagents, with the firm acknowledging their "unsanctioned use" in product lines tied to cancer research and viral vector production.[158] The Lacks estate filed lawsuits alleging unjust enrichment, arguing that firms reaped billions indirectly through HeLa-enabled innovations without equitable returns to the source, a claim rooted in the doctrine of accession where improvements to raw biological material generate proprietary value.[159][155] Legal actions highlighted systemic inequities: In October 2021, the Lacks family sued Thermo Fisher, leading to a confidential settlement on August 1, 2023, with no disclosed financial terms or judicial ruling on core liability.[160][161] Similar suits persist against entities like Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical for using HeLa in viral vectors and Novartis for biopharmaceutical applications, seeking profit shares under theories of conversion and misappropriation.[162][154] These cases underscore a historical precedent where empirical value from donor-derived lines—estimated to underpin over 100,000 scientific publications and unquantified industry revenues—accrued unilaterally to corporations, prompting debates on mandatory benefit-sharing frameworks akin to those in the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity for non-human genetic resources, though human tissues remain exempt under U.S. law post-2012 Supreme Court rulings on natural DNA patentability.[153][155] Broader implications for immortalized lines reveal analogous patterns, as commercialization often bypasses donors due to pre-1970s norms lacking informed consent or profit-sharing protocols, with academic sources noting that while peer-reviewed literature emphasizes scientific utility, it underreports economic disparities favoring industry over origins.[157] Reforms, such as the 2013 NIH agreement granting the Lacks family veto power over HeLa genomic data access, represent partial redress but do not extend to commercial sales, leaving unresolved the causal disconnect between donor sacrifice and downstream gains.[159] Ongoing litigation as of November 2024 against additional firms tests whether courts will impose retrospective equity, potentially reshaping access policies for lines like HeLa without retroactive revenue redistribution.[154]Moral Objections to Fetal and Abortion-Derived Lines

Moral objections to immortalized cell lines derived from fetal tissue obtained via elective abortions center on the principle that such derivations inherently involve the destruction of innocent human life, rendering their use ethically compromised regardless of downstream benefits. Pro-life advocates and ethicists argue that lines like WI-38 (established in 1962 from lung fibroblasts of a female fetus aborted for psychiatric reasons) and HEK-293 (derived in 1973 from kidney cells of a fetus aborted for unspecified reasons) perpetuate a moral wrong by commodifying the remains of unborn children killed in elective procedures.[163][164] This view holds that even remote material cooperation—through propagation and application in research, vaccine production, or drug testing—implicates users in the original act of abortion, as the cell lines' existence depends on that violence.[165] Evangelicals, for instance, contend that harvesting tissue from fetuses resulting from elective abortions violates the sanctity of human life from conception, equating it to benefiting from unjust killing and thus demanding absolute opposition to such research tools.[166] Critics further object that the lack of informed consent from the aborted fetus or, in some cases, the mother for research purposes undermines any claim to ethical legitimacy, treating nascent humans as mere biological resources without agency or rights.[167] Organizations like the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) emphasize that while therapeutic necessity might mitigate direct culpability in usage, the initial creation of these lines from procured abortions remains gravely immoral, and society should protest their normalization to avoid incentivizing future abortions by creating perceived demand for fetal material.[168] This concern is heightened by historical precedents, such as the development of WI-38 and the related MRC-5 line (from a 1966 abortion), where the procedures were not performed explicitly for scientific ends but were retroactively exploited, raising questions of opportunistic exploitation of abortion's consequences.[169] Pro-life groups argue that continued reliance on these lines—used in vaccines for rubella, varicella, and hepatitis A, among others—subsidizes an industry intertwined with abortion providers, potentially encouraging more procedures under the guise of medical progress.[170] Although some religious authorities, including the Pontifical Academy for Life in 2005, have deemed the use of existing abortion-derived lines morally tolerable in the absence of alternatives and with proportionate reasons (e.g., public health), objectors counter that this concession overlooks first-order moral hazards and fails to prioritize non-fetal alternatives like animal cells or recombinant technologies, which have advanced sufficiently to render fetal lines dispensable.[165][171] The Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith reiterated in 2020 that conscientious refusal remains valid for those viewing the connection to abortion as illicit, underscoring that vaccination obligations do not erase the underlying ethical stain.[172] Ethicists aligned with pro-life perspectives warn that habitual use entrenches a culture of disposability toward the unborn, where scientific utility justifies overlooking causal links to homicide, and advocate for ethical cell sourcing—such as from natural miscarriages or induced pluripotent stem cells—to sever this dependency.[173] These objections have fueled resistance, as seen in protests against COVID-19 vaccines tested or produced using HEK-293, where groups argued that even testing phases involve moral collaboration with abortion-derived materials.[174]Regulatory Oversight and Best Practices

Authentication Standards and Databases

Short tandem repeat (STR) profiling serves as the gold standard for authenticating human immortalized cell lines, generating a DNA fingerprint by amplifying and analyzing 8–18 polymorphic loci, including amelogenin for sex determination and markers for detecting cross-contamination such as HeLa or rodent cells.[126][175] This method, robust against genetic drift common in immortalized lines, achieves over 99% accuracy in matching profiles and is endorsed by the ANSI/ATCC ASN-0002 standard, which mandates its use for identity verification in research involving human cells.[132][176] Supplementary techniques, such as isoenzyme analysis for species verification or morphological examination, provide initial checks but lack the specificity of STR for unambiguous identification, particularly in cases of phenotypic drift or subcloning in immortalized cultures.[176] The International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC), established in 2012, promotes routine STR authentication to combat misidentification, estimating that up to 15–20% of cell lines in publications may be incorrect, a risk amplified in immortalized lines due to their proliferative nature and historical sharing without verification.[128] Many funding agencies and journals, including those under Nature Portfolio and Cell Press, require STR profiles no older than 3 years for studies using continuous human cell lines, ensuring profiles are compared against reference standards to confirm authenticity.[131][177] Key databases facilitate STR profile comparisons and authentication. The ATCC STR Database catalogs profiles for over 3,000 cell lines distributed by the repository, enabling direct matching and flagging of contaminants like HeLa in user samples.[178][176] The DSMZ database includes STR data for more than 1,000 human cell lines, emphasizing profiles beyond its collection to support global verification efforts.[179] NCBI's BioSample repository aggregates STR profiles from multiple sources, including ICLAC-contributed data on misidentified lines, allowing searches for matches or discrepancies in immortalized models.[180] ICLAC maintains a register of over 500 commonly misidentified cell lines, many immortalized, advising researchers to cross-check against this list before experiments to avoid propagation of errors. Complementary resources like Cellosaurus integrate STR data with metadata on origin and contamination history, while AuthentiCell provides a searchable interface for rapid human cell line matching against curated profiles.[181][182] These databases collectively mitigate risks in immortalized cell research by standardizing reference profiles and highlighting discrepancies, though gaps persist for non-human or proprietary lines.[183]Intellectual Property and Access Policies

Intellectual property rights over immortalized cell lines typically extend to engineered modifications, cultivation methods, or derivative inventions rather than the unmodified lines themselves, which courts have deemed unpatentable products of nature following the U.S. Supreme Court's 2012 decision in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics.[184] For instance, patents may cover immortalized lines altered via genetic engineering, such as those granted for specific human keratinocyte or pre-adipose cell lines, but require deposits in recognized repositories to enable enablement.[185] In the case of the HeLa cell line, derived from Henrietta Lacks in 1951, no patent was filed on the original cells, yet over 11,000 patents reference its use or derivatives, enabling commercialization by entities like Thermo Fisher Scientific without direct ownership claims on the source material.[186] Access to immortalized cell lines is regulated primarily through Material Transfer Agreements (MTAs), contractual documents that govern transfers between providers and recipients, specifying permitted uses, ownership retention by the provider, and intellectual property rights over inventions derived from the materials.[187][188] MTAs often prohibit commercial exploitation without negotiation, limit redistribution, and require attribution or return of derivatives, thereby balancing research dissemination with proprietary interests; for example, they may allow inventors to claim IP on tools developed from the lines while restricting the recipient's rights to the original material.[189][190] Repositories such as the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) enforce standardized MTAs to prevent misuse, though variations exist for sensitive lines like those from fetal or tumor sources. The HeLa line exemplifies tensions in access policies, particularly for genomic data. In 2013, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) established a controlled-access framework via the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP), requiring researchers to apply for HeLa whole-genome sequence data under a Data Use Agreement overseen by a working group including Lacks family representatives.[191][192] This agreement mandates adherence to terms prohibiting re-identification attempts and commercial use without further approval, addressing historical consent gaps while enabling scientific access; two family members review applications to ensure ethical alignment.[193][194] Ongoing litigation by the Lacks estate against commercial distributors invokes doctrines like unjust enrichment or accession to seek remedies, arguing that downstream value from HeLa exceeds original contributions without compensation, though courts have not yet granted ownership retroactively.[155][195] These policies underscore a shift toward benefit-sharing models, prioritizing verifiable provenance and equitable terms over unrestricted open access.Recent Advances and Future Prospects

CRISPR-Enhanced and Editable Immortalized Lines (Post-2020)

Following the widespread adoption of CRISPR-Cas9, post-2020 innovations have focused on enhancing immortalized cell lines through precise gene knockouts, knock-ins, and alternative editing modalities, yielding more genetically defined and editable models for research. These advancements mitigate off-target effects and enable targeted immortalization of primary cells by disrupting specific tumor suppressors, such as p53 or CDKN2A, without viral transduction risks. For example, in 2023, CRISPR-Cas9 targeting of the p53 gene or CDKN2A locus successfully immortalized primary marmoset skin fibroblasts, creating stable lines amenable to further CRISPR modifications for primate-specific studies.[196] A complementary approach reported the same year used CRISPR/Cas9 to excise exon 2 of CDKN2A in human primary cells, selectively ablating p16^INK4a and p14^ARF to bypass senescence while preserving other genomic integrity.[52] Efficiency in generating editable clones has improved via optimized single-guide RNA strategies. A 2023 protocol detailed CRISPR/Cas9-induced frameshift mutations in target genes of established immortalized lines, facilitating rapid single-cell cloning with high fidelity and low cost, applicable to drug screening and functional genomics.[197] Commercial providers have scaled these methods, offering pre-engineered immortalized knockout and knock-in lines—such as those with stable gene disruptions in HEK293 or cancer-derived cells—for reproducible gene function analysis and therapeutic target validation.[198][199] Precision editing tools like prime editing, advanced post-2020, further enhance immortalized lines by enabling scarless insertions, deletions, and base conversions without double-strand breaks, reducing unintended mutations in models like HepG2 liver cancer cells.00085-9) Recent applications include 2025 CRISPR engineering of fibroblast lines with RB1 stop codons to model retinoblastoma, providing editable platforms for oncogenic pathway dissection.[200] In hematopoietic contexts, immortalized lymphoblastoid and Jurkat lines have served as surrogates for CRISPR-based gene corrections in patient-derived models, accelerating validation before primary cell use.[201] These CRISPR-enhanced lines address historical inaccuracies in immortalized models by allowing causal dissection of genetic lesions, though challenges persist in validating edits against native tissue dynamics.[202] Ongoing refinements, including Cas variants with minimized off-target activity, continue to expand their utility in preclinical research.[203]Alternatives and Hybrids with Stem Cell Models

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and their derivatives offer a primary alternative to traditional immortalized cell lines by enabling the generation of patient-specific, differentiated cell types that more closely recapitulate native human physiology without the genetic instability and dedifferentiation associated with immortalization processes.[204] Unlike immortalized lines, which often accumulate mutations and lose tissue-specific characteristics over passages, iPSC-derived cells can be reprogrammed from somatic cells and directed toward lineages such as neurons, cardiomyocytes, or hepatocytes, supporting applications in drug screening and disease modeling.[205] For instance, in toxicology studies, iPSC-derived neuronal models have demonstrated greater relevance to human responses compared to immortalized lines like PC12 or SH-SY5Y, which exhibit altered signaling pathways due to oncogenic transformations.[206] Organoids, three-dimensional structures self-assembled from stem cells or tissue progenitors, further enhance this alternative by incorporating multicellular interactions, spatial organization, and microenvironmental cues absent in monolayer immortalized cultures.[207] Derived from iPSCs or primary tissues, organoids mimic organ-level complexity, as seen in intestinal organoids that replicate barrier function and inflammatory responses more accurately than Caco-2 immortalized lines, which fail to sustain long-term epithelial polarity.[208] Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) in oncology preserve tumor heterogeneity and genetic backgrounds, enabling personalized predictions of chemotherapy responses with higher concordance to clinical outcomes than uniform immortalized cancer cell lines like HeLa or MCF-7.[209] However, stem cell models face scalability challenges, with organoids requiring specialized matrices and showing batch-to-batch variability, contrasting the reproducibility of immortalized lines despite their physiological limitations.[210] Hybrid approaches integrate immortalized lines with stem cell-derived components to leverage the proliferative stability of the former and the fidelity of the latter, often through co-culture or fusion techniques. For example, fusing immortalized human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells with primary hepatocytes yields expandable hepatocyte-like hybrids that retain metabolic functions like cytochrome P450 activity for longer durations than either parent alone, addressing senescence in primary cells while avoiding full oncogenic immortalization.[211] In cancer research, spontaneous fusion between mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and breast cancer cell lines produces hybrids exhibiting enhanced metastatic traits and stem-like properties, such as increased tumorigenicity in xenografts, highlighting potential mechanisms of tumor evolution not observable in isolated immortalized models.[212] These hybrids, however, introduce complexities like unpredictable genomic rearrangements, necessitating rigorous validation to distinguish beneficial traits from artifacts.[213] Overall, while hybrids bridge gaps in model fidelity, their clinical translatability remains limited by fusion rarity and post-hybrid selection pressures that may amplify aggressive phenotypes.[214]Industry Growth and Technological Integration

The global market for immortalized cell lines, valued at approximately USD 4.5 billion in 2024, is projected to reach USD 6.9 billion by 2032, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 5.5%, driven primarily by expanding applications in pharmaceutical research, vaccine development, and toxicity testing.[215] This growth aligns with broader biotech sector investments, where immortalized lines provide reproducible models for high-throughput drug screening, reducing reliance on primary cells or animal models that introduce variability and ethical constraints.[84] Key demand stems from oncology and infectious disease research, with pharmaceutical firms accounting for over 50% of market share due to their use in validating therapeutic candidates prior to clinical trials.[216] Technological integration has accelerated industry scalability through automation and gene-editing tools, enabling faster development of customized lines for precision medicine. CRISPR-Cas9 and related systems have revolutionized immortalization by allowing targeted modifications to enhance cell stability and functionality, such as introducing telomerase or bypassing senescence pathways, which supports applications in regenerative therapies and personalized drug testing.[215] [217] Automation platforms, including robotic culturing systems and AI-driven predictive modeling, have reduced development timelines from months to weeks, improving throughput in biomanufacturing for biologics like monoclonal antibodies.[218] These advancements address historical limitations like genetic drift, with next-generation sequencing integrated for real-time authentication and quality control.[216] Hybrid integrations, such as combining immortalized lines with organ-on-chip technologies or 3D bioprinting, further propel growth by mimicking in vivo conditions more accurately than traditional 2D cultures, enhancing predictive accuracy for drug efficacy and safety.[84] Industry collaborations, including partnerships between biotech firms and contract research organizations, have expanded access to engineered lines, with North America holding over 40% market dominance due to robust R&D funding from entities like the National Institutes of Health.[219] Emerging epigenetic induction methods offer non-viral alternatives to viral immortalization, potentially mitigating risks of oncogenesis and broadening utility in therapeutic production.[220] Overall, these integrations underscore a shift toward sustainable, data-driven cell line engineering, though challenges like standardization persist amid rapid innovation.[221]References

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/[neuroscience](/page/Neuroscience)/immortalised-cell-line