Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chord (geometry)

View on Wikipedia

A chord (from the Latin chorda, meaning "catgut or string") of a circle is a straight line segment whose endpoints both lie on a circular arc. If a chord were to be extended infinitely on both directions into a line, the object is a secant line. The perpendicular line passing through the chord's midpoint is called sagitta (Latin for "arrow").

More generally, a chord is a line segment joining two points on any curve, for instance, on an ellipse. A chord that passes through a circle's center point is the circle's diameter.

In circles

[edit]Among properties of chords of a circle are the following:

- Chords are equidistant from the center if and only if their lengths are equal.

- Equal chords are subtended by equal angles from the center of the circle.

- A chord that passes through the center of a circle is called a diameter and is the longest chord of that specific circle.

- If the line extensions (secant lines) of chords AB and CD intersect at a point P, then their lengths satisfy AP·PB = CP·PD (power of a point theorem).

In conics

[edit]The midpoints of a set of parallel chords of a conic are collinear (midpoint theorem for conics).[1]

In trigonometry

[edit]

Chords were used extensively in the early development of trigonometry. The first known trigonometric table, compiled by Hipparchus in the 2nd century BC, is no longer extant but tabulated the value of the chord function for every 7+1/2 degrees. In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy compiled a more extensive table of chords in his book on astronomy, giving the value of the chord for angles ranging from 1/2 to 180 degrees by increments of 1/2 degree. Ptolemy used a circle of diameter 120, and gave chord lengths accurate to two sexagesimal (base sixty) digits after the integer part.[2]

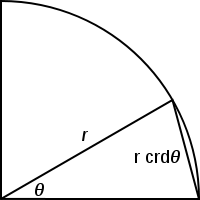

The chord function is defined geometrically as shown in the picture. The chord of an angle is the length of the chord between two points on a unit circle separated by that central angle. The angle θ is taken in the positive sense and must lie in the interval 0 < θ ≤ π (radian measure). The chord function can be related to the modern sine function, by taking one of the points to be (1,0), and the other point to be (cos θ, sin θ), and then using the Pythagorean theorem to calculate the chord length:[2]

The last step uses the half-angle formula. Much as modern trigonometry is built on the sine function, ancient trigonometry was built on the chord function. Hipparchus is purported to have written a twelve-volume work on chords, all now lost, so presumably, a great deal was known about them. In the table below (where c is the chord length, and D the diameter of the circle) the chord function can be shown to satisfy many identities analogous to well-known modern ones:

| Name | Sine-based | Chord-based |

|---|---|---|

| Pythagorean | ||

| Half-angle | ||

| Apothem (a) | ||

| Angle (θ) |

The inverse function exists as well:[4]

See also

[edit]- Circular segment – the part of the sector that remains after removing the triangle formed by the center of the circle and the two endpoints of the circular arc on the boundary.

- Scale of chords

- Ptolemy's table of chords

- Holditch's theorem, for a chord rotating in a convex closed curve

- Circle graph

- Exsecant and excosecant

- Versine and haversine – ()

- Zindler curve (closed and simple curve in which all chords that divide the arc length into halves have the same length)

- Bertrand paradox (probability) average length of chord paradox

References

[edit]- ^ Gibson, C. G. (2003). "7.1 Midpoint Loci". Elementary Euclidean Geometry: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 65–68. ISBN 9780521834483.

- ^ a b Maor, Eli (1998). Trigonometric Delights. Princeton University Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-0-691-15820-4.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Circular Segment". From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ^ Simpson, David G. (2001-11-08). "AUXTRIG" (FORTRAN-90 source code). Greenbelt, Maryland, US: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

External links

[edit]- History of Trigonometry Outline

- Trigonometric functions Archived 2017-03-10 at the Wayback Machine, focusing on history

- Chord (of a circle) With interactive animation