Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Color charge

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Standard Model of particle physics |

|---|

|

Color charge is a property of quarks and gluons that is related to the particles' strong interactions in the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD). Like electric charge, it determines how quarks and gluons interact through the strong force; however, rather than there being only positive and negative charges, there are three "charges", commonly called red, green, and blue. Additionally, there are three "anti-colors", commonly called anti-red, anti-green, and anti-blue. Unlike electric charge, color charge is never observed in nature: in all cases, red, green, and blue (or anti-red, anti-green, and anti-blue) or any color and its anti-color combine to form a "color-neutral" system. For example, the three quarks making up any baryon universally have three different color charges, and the two quarks making up any meson universally have opposite color charge.

The "color charge" of quarks and gluons is completely unrelated to the everyday meaning of color, which refers to the frequency of photons, the particles that mediate a different fundamental force, electromagnetism. The term color and the labels red, green, and blue became popular simply because of the loose but convenient analogy to the primary colors.

History

[edit]Shortly after the existence of quarks was proposed by Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964, color charge was implicitly introduced the same year by Oscar W. Greenberg.[1] In 1965, Moo-Young Han and Yoichiro Nambu explicitly introduced color as a gauge symmetry.[1]

Han and Nambu initially designated this degree of freedom by the group SU(3), but it was referred to in later papers as "the three-triplet model". One feature of the model (which was originally preferred by Han and Nambu) was that it permitted integrally charged quarks, as well as the fractionally charged quarks initially proposed by Zweig and Gell-Mann.

Somewhat later, in the early 1970s, Gell-Mann, in several conference talks, coined the name color to describe the internal degree of freedom of the three-triplet model, and advocated a new field theory, designated as quantum chromodynamics (QCD) to describe the interaction of quarks and gluons within hadrons. In Gell-Mann's QCD, each quark and gluon has fractional electric charge, and carries what came to be called color charge in the space of the color degree of freedom.

Red, green, and blue

[edit]In quantum chromodynamics (QCD), a quark's color can take one of three values or charges: red, green, and blue. An antiquark can take one of three anticolors: called antired, antigreen, and antiblue (represented as cyan, magenta, and yellow, respectively). Gluons are mixtures of two colors, such as red and antigreen, which constitutes their color charge. QCD considers eight gluons of the possible nine color–anticolor combinations to be unique; see eight gluon colors for an explanation.

All three colors mixed together, all three anticolors mixed together, or a combination of a color and its anticolor is "colorless" or "white" and has a net color charge of zero. Due to a property of the strong interaction called color confinement, free particles must have a color charge of zero.

A baryon is composed of three quarks, which must be one each of red, green, and blue colors; likewise an antibaryon is composed of three antiquarks, one each of antired, antigreen and antiblue. A meson is made from one quark and one antiquark; the quark can be any color, and the antiquark has the matching anticolor.

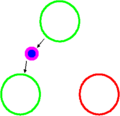

The following illustrates the coupling constants for color-charged particles:

-

The quark colors (red, green, blue) combine to be colorless

-

The quark anticolors (antired, antigreen, antiblue) also combine to be colorless

-

A hadron with 3 quarks (red, green, blue) before a color change

-

Blue quark emits a blue–antigreen gluon, becoming green

-

The first green quark has absorbed the blue–antigreen gluon and is now blue; color remains conserved

-

An animation of the interaction inside a neutron. The gluons are represented as circles with the color charge in the center and the anti-color charge on the outside.

Field lines from color charges

[edit]Analogous to an electric field and electric charges, the strong force acting between color charges can be depicted using field lines. However, the color field lines do not arc outwards from one charge to another as much, because they are pulled together tightly by gluons (within 1 fm).[2] This effect confines quarks within hadrons.

Top: Color charge has "ternary neutral states" as well as binary neutrality (analogous to electric charge).

Bottom: Quark/antiquark combinations.[3][4]

Coupling constant and charge

[edit]In a quantum field theory, a coupling constant and a charge are different but related notions. The coupling constant sets the magnitude of the force of interaction; for example, in quantum electrodynamics, the fine-structure constant is a coupling constant. The charge in a gauge theory has to do with the way a particle transforms under the gauge symmetry; i.e., its representation under the gauge group. For example, the electron has charge −1 and the positron has charge +1, implying that the gauge transformation has opposite effects on them in some sense. Specifically, if a local gauge transformation ϕ(x) is applied in electrodynamics, then one finds (using tensor index notation): where is the photon field, and ψ is the electron field with Q = −1 (a bar over ψ denotes its antiparticle – the positron). Since QCD is a non-abelian theory, the representations, and hence the color charges, are more complicated. They are dealt with in the next section.

Quark and gluon fields

[edit]

In QCD the gauge group is the non-abelian group SU(3). The running coupling is usually denoted by . Each flavour of quark belongs to the fundamental representation (3) and contains a triplet of fields together denoted by . The antiquark field belongs to the complex conjugate representation (3*) and also contains a triplet of fields. We can write

- and

The gluon contains an octet of fields (see gluon field), and belongs to the adjoint representation (8), and can be written using the Gell-Mann matrices as

(there is an implied summation over a = 1, 2, ... 8). All other particles belong to the trivial representation (1) of color SU(3). The color charge of each of these fields is fully specified by the representations. Quarks have a color charge of red, green or blue and antiquarks have a color charge of antired, antigreen or antiblue. Gluons have a combination of two color charges (one of red, green, or blue and one of antired, antigreen, or antiblue) in a superposition of states that are given by the Gell-Mann matrices. All other particles have zero color charge.

The gluons corresponding to and are sometimes described as having "zero charge" (as in the figure). Formally, these states are written as

- and

While "colorless" in the sense that they consist of matched color-anticolor pairs, which places them in the centre of a weight diagram alongside the truly colorless singlet state, they still participate in strong interactions - in particular, those in which quarks interact without changing color.

Mathematically speaking, the color charge of a particle is the value of a certain quadratic Casimir operator in the representation of the particle.

In the simple language introduced previously, the three indices "1", "2" and "3" in the quark triplet above are usually identified with the three colors. The colorful language misses the following point. A gauge transformation in color SU(3) can be written as , where is a 3 × 3 matrix that belongs to the group SU(3). Thus, after gauge transformation, the new colors are linear combinations of the old colors. In short, the simplified language introduced before is not gauge invariant.

Color charge is conserved, but the book-keeping involved in this is more complicated than just adding up the charges, as is done in quantum electrodynamics. One simple way of doing this is to look at the interaction vertex in QCD and replace it by a color-line representation. The meaning is the following. Let represent the ith component of a quark field (loosely called the ith color). The color of a gluon is similarly given by , which corresponds to the particular Gell-Mann matrix it is associated with. This matrix has indices i and j. These are the color labels on the gluon. At the interaction vertex one has qi → gij + qj. The color-line representation tracks these indices. Color charge conservation means that the ends of these color lines must be either in the initial or final state, equivalently, that no lines break in the middle of a diagram.

Since gluons carry color charge, two gluons can also interact. A typical interaction vertex (called the three gluon vertex) for gluons involves g + g → g. This is shown here, along with its color-line representation. The color-line diagrams can be restated in terms of conservation laws of color; however, as noted before, this is not a gauge invariant language. Note that in a typical non-abelian gauge theory the gauge boson carries the charge of the theory, and hence has interactions of this kind; for example, the W boson in the electroweak theory. In the electroweak theory, the W also carries electric charge, and hence interacts with a photon.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Greenberg, Oscar Wallace (2009), Greenberger, Daniel; Hentschel, Klaus; Weinert, Friedel (eds.), "Color Charge Degree of Freedom in Particle Physics", Compendium of Quantum Physics, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 109–111, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70626-7_32, ISBN 978-3-540-70626-7, retrieved 2024-09-17

- ^ R. Resnick, R. Eisberg (1985), Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles (2nd ed.), John Wiley & Sons, p. 684, ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0

- ^ Parker, C.B. (1994), McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.), Mc Graw Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-051400-3

- ^ M. Mansfield, C. O’Sullivan (2011), Understanding Physics (4th ed.), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-47-0746370

Further reading

[edit]- Georgi, Howard (1999), Lie algebras in particle physics, Perseus Books Group, ISBN 978-0-7382-0233-4.

- Griffiths, David J. (1987), Introduction to Elementary Particles, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-60386-3.

- Christman, J. Richard (2001), "Color and Charm" (PDF), PHYSNET document MISN-0-283.

- Hawking, Stephen (1998), A Brief History of Time, Bantam Dell Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-553-10953-5.

- Close, Frank (2007), The New Cosmic Onion, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-58488-798-0.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A_{\mu }&\to A_{\mu }+\partial _{\mu }\,\phi (x)\\\psi &\to \exp \left[+i\,Q\phi (x)\right]\;\psi \\{\bar {\psi }}&\to \exp \left[-i\,Q\phi (x)\right]\;{\bar {\psi }}~,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e95dbc8e4de7e10d356729b998cb570c3cda4f54)