Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Computer-aided engineering

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Engineering |

|---|

Computer-aided engineering (CAE) is the general usage of technology to aid in tasks related to engineering analysis.

Overview

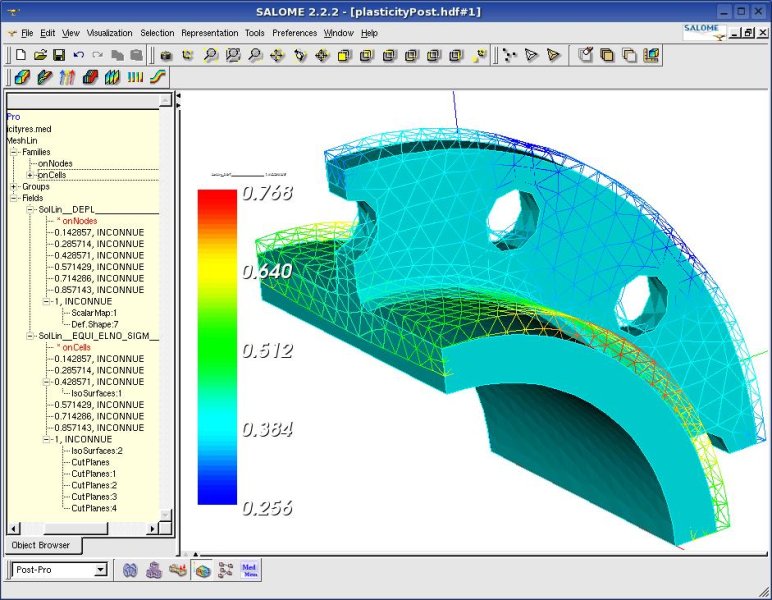

[edit]Computer-aided engineering (CAE) includes finite element method or analysis (FEA), computational fluid dynamics (CFD), multibody dynamics (MBD), durability and optimization. It is included with computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) in a collective term and abbreviation computer-aided technologies (CAx).

The term CAE has been used to describe the use of computer technology within engineering in a broader sense than just engineering analysis. It was in this context that the term was coined by Jason Lemon, founder of Structural Dynamics Research Corporation (SDRC) in the late 1970s. However, this definition is better known today by the terms CAx and product lifecycle management (PLM).[1]

CAE systems are individually considered a single node on a total information network, and each node may interact with other nodes on the network.

CAE fields and phases

[edit]CAE areas covered include:

- Stress analysis on components and assemblies using finite element analysis (FEA);

- Thermal and fluid flow analysis computational fluid dynamics (CFD);

- Multibody dynamics (MBD) and kinematics;

- Analysis tools for process simulation for operations such as casting, molding, and die press forming;

- Optimization of the product or process.

In general, there are three phases in any computer-aided engineering task:

- Pre-processing – defining the model and environmental factors to be applied to it (typically a finite element model, but facet, voxel, and thin sheet methods are also used);

- Analysis solver (usually performed on high powered computers);

- Post-processing of results (using visualization tools).

This cycle is iterated either manually or with the use of commercial optimization software.

CAE in the automotive industry

[edit]CAE tools are widely used in the automotive industry. Their use has enabled automakers to reduce product development costs and time while improving the safety, comfort, and durability of the vehicles they produce. The predictive capability of CAE tools has progressed to the point where much of the design verification is done using computer simulations (diagnosis) rather than physical prototype testing. CAE dependability is based upon all proper assumptions as inputs and must identify critical inputs (BJ). Even though there have been many advances in CAE, and it is widely used in the engineering field, physical testing is still a must. It is used for verification and model updating, to accurately define loads and boundary conditions, and for final prototype sign-off.

The future of CAE in the product development process

[edit]Even though CAE has built a strong reputation as a verification, troubleshooting and analysis tool, there is still a perception that sufficiently accurate results come rather late in the design cycle to really drive the design. This can be expected to become a problem as modern products become ever more complex. They include smart systems, which leads to an increased need for multi-physics analysis including controls, and contain new lightweight materials, with which engineers are often less familiar. CAE software companies and manufacturers are constantly looking for tools and process improvements to change this situation.

On the software side, they are constantly looking to develop more powerful solvers, to better utilize computer resources, and to include engineering knowledge in pre and post-processing. Recent developments have seen the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into CAE tools, enabling real-time simulations and predictive modeling.[2] On the process side, they try to achieve a better alignment between 3D CAE, 1D system simulation, and physical testing. This should increase modeling realism and calculation speed.

CAE software companies and manufacturers try to better integrate CAE in the overall product lifecycle management. In this way they can connect product design with product use, which is needed for smart products. This enhanced engineering process is also referred to as predictive engineering analytics.[3][4]

See also

[edit]- Multiphysics simulation

- List of finite element software packages

- Computer representation of surfaces

- Computational electromagnetics (CEM)

- Electronic design automation (EDA)

- Multidisciplinary design optimization (MDO)

- Comparison of CAD editors for CAE

- Virtual prototyping

- Finite element updating

- Predictive engineering analytics

- VE-Suite

- List of computer-aided engineering software

References

[edit]- ^ Marks, Peter. "2007: In Remembrance of Dr. Jason A. Lemon, CAE pioneer". gfxspeak.com. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ Kohar, Christopher P.; Greve, Lars; Eller, Tom K.; Connolly, Daniel S.; Inal, Kaan (2021-11-01). "A machine learning framework for accelerating the design process using CAE simulations: An application to finite element analysis in structural crashworthiness". Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering. 385 114008. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2021.114008. ISSN 0045-7825.

- ^ Van der Auweraer, Herman; Anthonis, Jan; De Bruyne, Stijn; Leuridan, Jan (2012). "Virtual engineering at work: the challenges for designing mechatronic products". Engineering with Computers. 29 (3): 389–408. doi:10.1007/s00366-012-0286-6.

- ^ Seong Wook Cho; Seung Wook Kim; Jin-Pyo Park; Sang Wook Yang; Young Choi (2011). "Engineering collaboration framework with CAE analysis data". International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing. 12.

Further reading

[edit]- B. Raphael and I.F.C. Smith (2003). Fundamentals of computer aided engineering. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-48715-9.