Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Structural formula

View on Wikipedia

The structural formula of a chemical compound is a graphic representation of the molecular structure (determined by structural chemistry methods), showing how the atoms are connected to one another.[1] The chemical bonding within the molecule is also shown, either explicitly or implicitly. Unlike other chemical formula types,[a] which have a limited number of symbols and are capable of only limited descriptive power, structural formulas provide a more complete geometric representation of the molecular structure. For example, many chemical compounds exist in different isomeric forms, which have different enantiomeric structures but the same molecular formula. There are multiple types of ways to draw these structural formulas such as: Lewis structures, condensed formulas, skeletal formulas, Newman projections, Cyclohexane conformations, Haworth projections, and Fischer projections.[3]

Several systematic chemical naming formats, as in chemical databases, are used that are equivalent to, and as powerful as, geometric structures. These chemical nomenclature systems include SMILES, InChI and CML. These systematic chemical names can be converted to structural formulas and vice versa, but chemists nearly always describe a chemical reaction or synthesis using structural formulas rather than chemical names, because the structural formulas allow the chemist to visualize the molecules and the structural changes that occur in them during chemical reactions. ChemSketch and ChemDraw are popular downloads/websites that allow users to draw reactions and structural formulas, typically in the Lewis Structure style.

Structures in structural formulas

[edit]Bonds

[edit]Bonds are often shown as a line that connects one atom to another. One line indicates a single bond. Two lines indicate a double bond, and three lines indicate a triple bond. In some structures the atoms in between each bond are specified and shown. However, in some structures, the carbon molecules are not written out specifically. Instead, these carbons are indicated by a corner that forms when two lines connect. Additionally, Hydrogen atoms are implied and not usually drawn out. These can be inferred based on how many other atoms the carbon is attached to. For example, if Carbon A is attached to one other Carbon B, Carbon A will have three hydrogens in order to fill its octet.[4]

|

|

Electrons

[edit]

Electrons are usually shown as colored-in circles. One circle indicates one electron. Two circles indicate a pair of electrons. Typically, a pair of electrons will also indicate a negative charge. By using the colored circles, the number of electrons in the valence shell of each respective atom is indicated, providing further descriptive information regarding the reactive capacity of that atom in the molecule.[4]

Charges

[edit]Oftentimes, atoms will have a positive or negative charge as their octet may not be complete. If the atom is missing a pair of electrons or has a proton, it will have a positive charge. If the atom has electrons that are not bonded to another atom, there will be a negative charge. In structural formulas, the positive charge is indicated by ⊕, and the negative charge is indicated by ⊖ .[4]

Stereochemistry (Skeletal formula)

[edit]

Chirality in skeletal formulas is indicated by the Natta projection method. Stereochemistry is used to show the relative spatial arrangement of atoms in a molecule. Wedges are used to show this, and there are two types: dashed and filled. A filled wedge indicates that the atom is in the front of the molecule; it is pointing above the plane of the paper towards the front. A dashed wedge indicates that the atom is behind the molecule; it is pointing below the plane of the paper. When a straight, un-dashed line is used, the atom is in the plane of the paper. This spatial arrangement provides an idea of the molecule in a 3-dimensional space and there are constraints as to how the spatial arrangements can be arranged.[4]

Unspecified stereochemistry

[edit]

Wavy single bonds represent unknown or unspecified stereochemistry or a mixture of isomers. For example, the adjacent diagram shows the fructose molecule with a wavy bond to the HOCH2− group at the left. In this case the two possible ring structures are in chemical equilibrium with each other and also with the open-chain structure. The ring automatically opens and closes, sometimes closing with one stereochemistry and sometimes with the other.[citation needed]

Skeletal formulas can depict cis and trans isomers of alkenes. Wavy single bonds are the standard way to represent unknown or unspecified stereochemistry or a mixture of isomers (as with tetrahedral stereocenters). A crossed double-bond has been used sometimes, but is no longer considered an acceptable style for general use.[5]

Lewis structures

[edit]

Lewis structures (or "Lewis dot structures") are flat graphical formulas that show atom connectivity and lone pair or unpaired electrons, but not three-dimensional structure. This notation is mostly used for small molecules. Each line represents the two electrons of a single bond. Two or three parallel lines between pairs of atoms represent double or triple bonds, respectively. Alternatively, pairs of dots may be used to represent bonding pairs. In addition, all non-bonded electrons (paired or unpaired) and any formal charges on atoms are indicated. Through the use of Lewis structures, the placement of electrons, whether it is in a bond or in lone pairs, will allow for the identification of the formal charges of the atoms in the molecule to understand the stability and determine the most likely molecule (based on molecular geometry difference) that would be formed in a reaction. Lewis structures do give some thought to the geometry of the molecule as oftentimes, the bonds are drawn at certain angles to represent the molecule in real life. Lewis structure is best used to calculate formal charges or how atoms bond to each other as both electrons and bonds are shown. Lewis structures give an idea of the molecular and electronic geometry which varies based on the presence of bonds and lone pairs and through this one could determine the bond angles and hybridization as well.

-

The Lewis structure of water

Condensed formulas

[edit]In early organic-chemistry publications, where use of graphics was strongly limited, a typographic system arose to describe organic structures in a line of text. Although this system tends to be problematic in application to cyclic compounds, it remains a convenient way to represent simple structures:

- CH3CH2OH (ethanol)

Parentheses are used to indicate multiple identical groups, indicating attachment to the nearest non-hydrogen atom on the left when appearing within a formula, or to the atom on the right when appearing at the start of a formula:

- (CH3)2CHOH or CH(CH3)2OH (2-propanol)

In all cases, all atoms are shown, including hydrogen atoms. It is also helpful to show the carbonyls where the C=O is implied through the O being placed in the parentheses. For example:

- CH3C(O)CH3 (acetone)

Therefore, it is important to look to the left of the atom in the parentheses to make sure what atom it is attached to. This is helpful when converting from condensed formula to another form of structural formula such as skeletal formula or Lewis structures. There are different ways to show the various functional groups in the condensed formulas such as aldehyde as CHO, carboxylic acids as CO2H or COOH, esters as CO2R or COOR. However, the use of condensed formulas does not give an immediate idea of the molecular geometry of the compound or the number of bonds between the carbons, it needs to be recognized based on the number of atoms attached to the carbons and if there are any charges on the carbon.[6]

Skeletal formulas

[edit]Skeletal formulas are the standard notation for more complex organic molecules. In this type of diagram, first used by the organic chemist Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz,[7] the carbon atoms are implied to be located at the vertices (corners) and ends of line segments rather than being indicated with the atomic symbol C. Hydrogen atoms attached to carbon atoms are not indicated: each carbon atom is understood to be associated with enough hydrogen atoms to give the carbon atom four bonds. The presence of a positive or negative charge at a carbon atom takes the place of one of the implied hydrogen atoms. Hydrogen atoms attached to atoms other than carbon must be written explicitly. An additional feature of skeletal formulas is that by adding certain structures the stereochemistry, that is the three-dimensional structure, of the compound can be determined. Often times, the skeletal formula can indicate stereochemistry through the use of wedges instead of lines. Solid wedges represent bonds pointing above the plane of the paper, whereas dashed wedges represent bonds pointing below the plane.

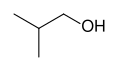

-

Skeletal formula of isobutanol, (CH3)2CHCH2OH

Perspective drawings

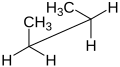

[edit]Newman projection and sawhorse projection

[edit]The Newman projection and the sawhorse projection are used to depict specific conformers or to distinguish vicinal stereochemistry. In both cases, two specific carbon atoms and their connecting bond are the center of attention. The only difference is a slightly different perspective: the Newman projection looking straight down the bond of interest, the sawhorse projection looking at the same bond but from a somewhat oblique vantage point. In the Newman projection, a circle is used to represent a plane perpendicular to the bond, distinguishing the substituents on the front carbon from the substituents on the back carbon. In the sawhorse projection, the front carbon is usually on the left and is always slightly lower. Sometimes, an arrow is used to indicate the front carbon. The sawhorse projection is very similar to a skeletal formula, and it can even use wedges instead of lines to indicate the stereochemistry of the molecule. The sawhorse projection is set apart from the skeletal formulas because the sawhorse projection is not a very good indicator of molecule geometry and molecular arrangement. Both a Newman and Sawhorse Projection can be used to create a Fischer Projection.[citation needed]

-

Newman projection of butane

-

Sawhorse projection of butane

Cyclohexane conformations

[edit]Certain conformations of cyclohexane and other small-ring compounds can be shown using a standard convention. For example, the standard chair conformation of cyclohexane involves a perspective view from slightly above the average plane of the carbon atoms and indicates clearly which groups are axial (pointing vertically up or down) and which are equatorial (almost horizontal, slightly slanted up or down). Bonds in front may or may not be highlighted with stronger lines or wedges. The conformations progress as follows: chair to half-chair to twist-boat to boat to twist-boat to half-chair to chair. The cyclohexane conformations may also be used to show the potential energy present at each stage as shown in the diagram. The chair conformations (A) have the lowest energy, whereas the half-chair conformations (D) have the highest energy. There is a peak/local maximum at the boat conformation (C), and there are valleys/local minimums at the twist-boat conformations (B). In addition, cyclohexane conformations can be used to indicate if the molecule has any 1,3 diaxial-interactions which are steric interactions between axial substituents on the 1,3, and 5 carbons.[8]

|

|

Haworth projection

[edit]The Haworth projection is used for cyclic sugars. Axial and equatorial positions are not distinguished; instead, substituents are positioned directly above or below the ring atom to which they are connected. Hydrogen substituents are typically omitted.

However, an important thing to keep in mind while reading an Haworth projection is that the ring structures are not flat. Therefore, Haworth does not provide 3-D shape. Sir Norman Haworth, was a British Chemist, who won a Nobel Prize for his work on Carbohydrates and discovering the structure of Vitamin C. During his discovery, he also deducted different structural formulas which are now referred to as Haworth Projections. In a Haworth Projection a pyranose sugar is depicted as a hexagon and a furanose sugar is depicted as a pentagon. Usually an oxygen is placed at the upper right corner in pyranose and in the upper center in a furanose sugar. The thinner bonds at the top of the ring refer to the bonds as being farther away and the thicker bonds at the bottom of the ring refer to the end of the ring that is closer to the viewer.[9]

|

|

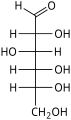

Fischer projection

[edit]The Fischer projection is mostly used for linear monosaccharides. At any given carbon center, vertical bond lines are equivalent to stereochemical hashed markings, directed away from the observer, while horizontal lines are equivalent to wedges, pointing toward the observer. The projection is unrealistic, as a saccharide would never adopt this multiply eclipsed conformation. Nonetheless, the Fischer projection is a simple way of depicting multiple sequential stereocenters that does not require or imply any knowledge of actual conformation. A Fischer projection will restrict a 3-D molecule to 2-D, and therefore, there are limitations to changing the configuration of the chiral centers. Fischer projections are used to determine the R and S configuration on a chiral carbon and it is done using the Cahn Ingold Prelog rules. It is a convenient way to represent and distinguish between enantiomers and diastereomers.[9]

-

Fischer projection of D-Glucose

Limitations

[edit]A structural formula is a simplified model that cannot represent certain aspects of chemical structures. For example, formalized bonding may not be applicable to dynamic systems such as delocalized bonds. Aromaticity is such a case and relies on convention to represent the bonding. Different styles of structural formulas may represent aromaticity in different ways, leading to different depictions of the same chemical compound. Another example is formal double bonds where the electron density is spread outside the formal bond, leading to partial double bond character and slow inter-conversion at room temperature. For all dynamic effects, temperature will affect the inter-conversion rates and may change how the structure should be represented. There is no explicit temperature associated with a structural formula, although many assume that it would be standard temperature.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Olmsted, John; Williams, Gregory M. (1997). Chemistry: The Molecular Science. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-8151-8450-8.

- ^ Denise DeCooman (2022-04-08). "What are Chemical Formulas and How are They Used?". Study.com. sec. Chemical Formula Examples. Archived from the original on 2022-06-23.

- ^ Goodwin, W. M. (2007-04-13). "Structural formulas and explanation in organic chemistry". Foundations of Chemistry. 10 (2): 117–127. doi:10.1007/s10698-007-9033-2. ISSN 1386-4238. S2CID 93952251.

- ^ a b c d Brown, William Henry; Brent L. Iverson; Eric V. Anslyn; Christopher S. Foote (2018). Organic chemistry (Eighth ed.). Boston. ISBN 978-1-305-58035-0. OCLC 974377227.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ J. Brecher (2006). "Graphical representation of stereochemical configuration (IUPAC Recommendations 2006)" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 78 (10): 1897–1970. doi:10.1351/pac200678101897. S2CID 97528124.

- ^ Liu, Xin (2021), "2.1 Structures of Alkenes", Organic Chemistry I, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, ISBN 9781989864524, retrieved 2025-06-28

- ^ "Friedrich August Kekule von Stradonitz –inventor of benzene structure - World Of Chemicals". www.worldofchemicals.com. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ Brown, William Henry (2018). Organic chemistry. Brent L. Iverson, Eric V. Anslyn, Christopher S. Foote (Eighth ed.). Boston, MA. ISBN 978-1-305-58035-0. OCLC 974377227.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Zhang, Qing-zhi; Zhang, Shen-song (June 1999). "A New Method To Convert the Fischer Projection of a Monosaccharide to the Haworth Projection". Journal of Chemical Education. 76 (6): 799. doi:10.1021/ed076p799. ISSN 0021-9584.

External links

[edit]- The Importance of Structural Formulas

- "Structural Formulas". 2016-05-09. Archived from the original on 2016-05-09. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- How to get structural formulas using crystallography

Structural formula

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Structural Formulas

Definition and Purpose

A structural formula is a diagrammatic representation that depicts the arrangement of atoms within a molecule, explicitly showing the connections between atoms via chemical bonds, in contrast to a molecular formula, which only specifies the types and numbers of atoms present without indicating their linkages.[6] For instance, the molecular formula C₆H₆ represents benzene but does not reveal its cyclic structure, whereas a structural formula illustrates the hexagonal ring of carbon atoms with alternating double bonds.[3] This distinction is crucial because molecular formulas alone cannot differentiate between compounds with the same atomic composition but different connectivities, such as the various isomers of C₄H₁₀O.[3] The concept of structural formulas originated in the 19th century, pioneered by chemists seeking to explain the valence and connectivity in organic molecules. Friedrich August Kekulé played a pivotal role in 1858 by proposing that carbon atoms could form chains, establishing tetravalency as a key principle, and in 1865, he introduced the cyclic structural formula for benzene, depicting it as a ring of six carbon atoms to account for its stability and reactivity.[7] This innovation marked a shift from empirical observations to visual models of molecular architecture, enabling chemists to represent bonding patterns systematically.[8] Structural formulas serve to elucidate isomerism by highlighting variations in atomic connectivity, which lead to distinct molecular behaviors despite identical molecular formulas; for example, they distinguish n-butane from isobutane, both C₄H₁₀, by showing linear versus branched chains.[3] They also facilitate the depiction of reaction mechanisms, allowing chemists to trace bond breaking and forming in stepwise processes, as seen in illustrations of nucleophilic substitutions where explicit bond arrangements clarify intermediate structures.[9] Furthermore, by revealing bonding patterns, structural formulas help predict physical properties influenced by molecular shape, such as boiling points differing between straight-chain and branched alkanes due to variations in intermolecular forces.[3]Representation of Bonds

In structural formulas, covalent bonds are visually represented by lines connecting atomic symbols, with the type of bond indicated by the number and style of lines used. A single bond, involving the sharing of one pair of electrons between two atoms, is depicted as a single solid straight line; for instance, the C-H bonds in methane are shown this way. Double bonds, which share two electron pairs, are represented by two parallel solid lines, as seen in the C=O bond of formaldehyde (H₂C=O). Triple bonds, sharing three electron pairs, use three parallel lines, such as in the N≡N bond of nitrogen gas. Non-covalent interactions, like hydrogen bonds or van der Waals forces, are conventionally shown with dashed lines to distinguish them from covalent linkages, emphasizing their weaker nature without implying electron sharing.[10][11][12] These representations adhere to fundamental valence rules, ensuring that atoms achieve stable electron configurations as per the octet rule for elements in the second period of the periodic table, where eight valence electrons are typically sought. In depictions, this means carbon, for example, forms four bonds to complete its octet, as illustrated in methane (CH₄), where the central carbon connects to four hydrogens via single bonds, each hydrogen satisfying its duet rule with one bond. Similar conventions apply to other atoms: oxygen often forms two bonds and has two lone pairs (implied in basic structural formulas), while nitrogen forms three bonds and one lone pair. Violations of the octet rule occur in certain cases, such as with elements beyond the second period, but standard organic structural formulas prioritize octet compliance for main-group elements unless exceptions like boron compounds (e.g., BF₃ with six electrons around boron) are specified.[13][14] For aromatic compounds, bond representation departs from simple alternating single and double bonds to convey delocalization. In benzene (C₆H₆), the classic Kekulé structure uses three alternating double bonds in a hexagonal ring to suggest resonance, but a more accurate notation employs a circle inscribed within the hexagon to symbolize the uniform, delocalized π-electron cloud across all six C-C bonds, each of equal length (approximately 1.39 Å). This circle convention highlights the stability of the aromatic system without implying localized double bonds.[15] Although two-dimensional structural formulas do not explicitly depict angles, they implicitly convey standard molecular geometries based on hybridization and valence electron pairs. For sp³-hybridized carbons with four single bonds, a tetrahedral arrangement with bond angles of about 109.5° is assumed, as in the carbon framework of alkanes; deviations, such as in cyclopropane's strained 60° angles, are noted separately but not shown in basic line drawings. This implicit geometry aids in understanding reactivity and shape without requiring three-dimensional projections.[16]Representation of Electrons and Charges

In structural formulas, non-bonding electrons, known as lone pairs, are represented by pairs of dots placed adjacent to the atom to which they belong, illustrating the complete valence electron configuration without overlapping with bond representations. For example, in the water molecule (H₂O), the oxygen atom is depicted with two lone pairs as four dots (two pairs) positioned above and below the atom, alongside its two single bonds to hydrogen atoms. This notation emphasizes the octet rule fulfillment for second-period elements, where lone pairs contribute to the atom's stability.[17] Formal charges on atoms within a structural formula are indicated by superscript numbers placed next to the atom, such as +1 or -1, to denote deviations from neutrality due to electron distribution in bonds and lone pairs. The formal charge is calculated using the formula: For instance, in a carbocation like the methyl cation (CH₃⁺), the central carbon bears a +1 formal charge as a superscript, reflecting its six valence electrons (three from bonds and none non-bonding) compared to its group 4A valence of four. This convention helps identify reactive sites and validate resonance structures in molecules. Unpaired electrons, characteristic of radicals, are shown as a single dot adjacent to the atom or group, distinguishing them from paired lone pairs or shared bonding electrons. In the methyl radical (CH₃•), the dot follows the formula to signify the carbon's unpaired electron, highlighting its high reactivity and odd-electron nature. This simple dot notation is essential for depicting species involved in chain reactions and organic synthesis./01%3A_Structure_and_Bonding/1.04%3A_Lewis_Structures_Continued) For polyatomic ions, the entire structural formula is enclosed in square brackets, with the net ionic charge indicated as a superscript outside the brackets to convey the overall electron imbalance distributed across the ion. The sulfate ion, for example, is represented as [O₃S(=O)₂]²⁻ (or in dot notation with lone pairs), where the 2- charge outside the brackets accounts for the two extra electrons beyond neutral sulfur and oxygen valences. This bracketing ensures clarity in ionic compounds and distinguishes the ion from neutral molecules.Planar Structural Representations

Lewis Structures

Lewis structures, also known as Lewis dot diagrams or electron-dot structures, represent the arrangement of valence electrons in atoms, ions, and molecules, illustrating covalent bonds as shared electron pairs and lone pairs on atoms. Developed by Gilbert N. Lewis in his 1916 paper "The Atom and the Molecule," these diagrams emphasize the role of valence electrons in forming stable octet configurations, where most atoms achieve eight electrons in their outer shells to mimic noble gas stability.[18] This approach provides a visual tool for predicting molecular geometry, reactivity, and bonding without delving into quantum mechanics. The construction of a Lewis structure involves a step-by-step process to ensure accurate electron distribution:- Calculate the total number of valence electrons by summing the valence electrons from all atoms in the formula, adding electrons for negative charges or subtracting for positive charges.[19]

- Sketch the skeletal framework by arranging atoms, placing the central atom (typically the least electronegative, excluding hydrogen) and connecting others with single bonds represented as lines or pairs of dots.[19]

- Distribute the remaining valence electrons as lone pairs to peripheral atoms first, aiming to complete their octets (or duets for hydrogen).[19]

- Assign any leftover electrons to the central atom; if its octet is incomplete, form multiple bonds by converting lone pairs into shared double or triple bonds as needed.[19]

Condensed Formulas

Condensed structural formulas represent the connectivity of atoms in a molecule using a linear, text-based notation that omits explicit bond lines while grouping atoms and substituents to convey structure efficiently.[3] This format is particularly useful in organic chemistry for depicting carbon chains and branches without the visual complexity of full diagrams.[23] The notation relies on implied single bonds between adjacent atoms, with carbon atoms assumed at intersections or chains unless specified otherwise, and hydrogen atoms grouped directly with their attached carbons using subscripts for multiples.[3] Parentheses are employed to indicate branches or substituents attached to the same atom, ensuring clarity in non-linear arrangements; for example, isobutane (2-methylpropane) is written as CH₃CH(CH₃)CH₃, where the parentheses denote the methyl group branching from the second carbon.[23] In straight-chain alkanes, repeating units are abbreviated, as in n-octane represented as CH₃(CH₂)₆CH₃, which compactly shows the six methylene groups between terminal methyls.[3] One key advantage of condensed formulas is their compactness, making them ideal for describing long or repetitive carbon chains without drawing extensive lines, thus facilitating quick communication in chemical literature and calculations.[14] This brevity retains essential connectivity information while reducing the space required compared to expanded structural representations.[3] However, condensed formulas can introduce limitations in clarity, particularly with complex branching, where ambiguity arises if parentheses are omitted or misinterpreted, potentially leading to confusion between isomers.[14] Proper use of grouping symbols is essential to avoid such issues, though they do not depict three-dimensional aspects or multiple bonds as explicitly as other notations.[3] To convert a Lewis structure to a condensed formula, remove all explicit bond lines and electron dots, then group hydrogen atoms with their respective carbons, using subscripts for identical groups and parentheses for branches to preserve the skeletal arrangement.[3] This process simplifies the visual while maintaining the molecular topology.[23] Skeletal formulas serve as further simplifications by omitting hydrogen indications entirely.[14]Skeletal Formulas

Skeletal formulas, also known as line-angle or bond-line notations, provide a streamlined visual representation of organic molecules by emphasizing the connectivity of the carbon framework. In this system, each vertex or terminus of a line denotes a carbon atom, while the lines themselves signify covalent bonds, with single bonds as solid lines and double bonds as paired lines or indicated explicitly. Hydrogen atoms attached to carbon are routinely omitted, as they are inferred to satisfy the four-valence requirement of carbon, thereby reducing visual complexity without sacrificing essential structural information.[24] To reflect the tetrahedral arrangement around carbon atoms, linear chains in skeletal formulas are conventionally drawn in a zig-zag pattern, where each segment represents a C-C bond angled to mimic bond angles near 109.5°. This approach facilitates quick recognition of chain length and branching, as intersections indicate branch points or ring closures. For cyclic structures, bonds form closed polygons, with benzene commonly illustrated as a regular hexagon featuring three alternating double bonds to denote its conjugated system, or equivalently, a hexagon enclosing a circle to symbolize uniform electron delocalization across the ring.[25]/15%3A_Benzene_and_Aromatic_Compounds/15.02%3A_The_Structure_of_Benzene) In organic chemistry, skeletal formulas serve as the standard for illustrating intricate molecules like steroids, which possess a characteristic tetracyclic core of three six-membered rings fused to one five-membered ring, allowing chemists to focus on functional group placements and stereocenters amid dense connectivity. Heteroatoms, such as oxygen or nitrogen, are explicitly labeled with their atomic symbols at bond junctions or ends, and lone pair electrons may be depicted as dots when clarification of reactivity or charge is required, though they are frequently implied based on standard valences.[26][24] Basic skeletal formulas assume a two-dimensional planar layout, though wedge and dash notations can be incorporated briefly to denote stereochemistry at chiral centers.Stereochemical and Perspective Representations

Basic Stereochemistry Notation

Basic stereochemistry notation in structural formulas provides a two-dimensional method to indicate the spatial arrangement of atoms around chiral centers and double bonds, allowing chemists to depict stereoisomers without requiring full three-dimensional models. These notations are essential for representing molecules where the arrangement of substituents affects properties such as reactivity and biological activity. Commonly applied to planar representations like skeletal formulas, they use simple line conventions to convey depth or relative positioning.[27] For chiral centers, typically tetrahedral carbon atoms with four different substituents, wedge and dash notations specify whether a bond projects toward or away from the viewer. A solid wedge represents a substituent coming out of the plane toward the observer, while a dashed line or hashed wedge indicates a substituent receding behind the plane. These conventions, with the narrow end of the wedge attached to the stereogenic center, unambiguously define the absolute configuration in a perspective drawing. For example, in (2R,3R)-tartaric acid, solid wedges are used for the hydroxyl groups projecting forward. Hashed lines, consisting of parallel short dashes, are an alternative to plain dashed lines for enhanced clarity in printed media.[28][27] In alkenes and other compounds with restricted rotation around double bonds, cis-trans isomerism is denoted by the relative positioning of substituents on adjacent carbons. When the double bond is represented linearly, forward slashes (/) and backslashes () on the connecting bonds indicate whether substituents are on the same (cis) or opposite (trans) sides; for instance, in (E)-2-butene, the methyl groups are shown with opposing slashes to denote trans configuration. This slash notation is particularly useful in condensed or skeletal structural formulas to avoid ambiguity in chain depictions. For more complex cases where substituents differ, the E/Z system supersedes cis/trans, but the slash method remains a visual aid in drawings.[29][30] When the stereochemistry at a center or double bond is unspecified or represents a mixture, wavy lines are employed to connect substituents, signaling an unknown or racemic configuration without implying a specific arrangement. The "rac" prefix may accompany such drawings to explicitly denote a racemic mixture of enantiomers. According to IUPAC guidelines, wavy bonds should be used judiciously, often with accompanying text for clarity, and are preferred over plain bonds when stereochemistry is intentionally ambiguous.[27] To assign absolute configuration at chiral centers in these notations, the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority rules are applied: substituents are ranked by atomic number (or further by attached atoms), the lowest-priority group is oriented away, and the configuration is designated R (clockwise) or S (counterclockwise) when viewing the remaining groups in decreasing priority. This system integrates seamlessly with wedge-dash drawings by determining the order after establishing the perspective. The CIP rules, formalized in 1966, ensure consistent nomenclature across structural representations.[31]Fischer Projections

Fischer projections are a two-dimensional convention for depicting the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in molecules with multiple chiral centers, particularly useful for linear representations of biomolecules. Developed by German chemist Emil Fischer in 1891 to elucidate the stereochemistry of carbohydrates, this method simplifies the visualization of tetrahedral geometries by projecting the molecule onto a plane while adhering to specific orientation rules.[32] The standard drawing rules for Fischer projections position the main carbon chain vertically, with the most oxidized carbon (such as a carbonyl group) placed at the top and the least oxidized at the bottom. Horizontal bonds are understood to project forward out of the plane of the paper toward the viewer, while vertical bonds extend backward behind the plane. This eclipsed conformation assumes all bonds are in the same plane for simplicity, though actual molecules adopt staggered arrangements; the projection prioritizes stereochemical clarity over conformational accuracy.[33][34] A classic example is the Fischer projection of D-glucose, an aldohexose, which illustrates the D configuration through the positioning of hydroxyl groups. The open-chain form is drawn as follows, with the aldehyde at the top and the CH₂OH at the bottom: CHO

|

H-C-OH

|

HO-C-H

|

H-C-OH

|

H-C-OH

|

CH₂OH

CHO

|

H-C-OH

|

HO-C-H

|

H-C-OH

|

H-C-OH

|

CH₂OH