Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Zoonosis

View on Wikipedia

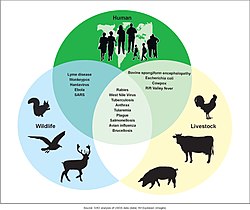

A zoonosis (/zoʊˈɒnəsɪs, ˌzoʊəˈnoʊsɪs/ ⓘ;[1] plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a virus, bacterium, parasite, fungi, or prion) that can jump from a non-human vertebrate to a human. When humans infect non-humans, it is called reverse zoonosis or anthroponosis.[2][1][3][4]

Major modern diseases such as Ebola and salmonellosis are zoonoses. HIV was a zoonotic disease transmitted to humans in the early part of the 20th century, though it has now evolved into a separate human-only disease.[5][6][7] Human infection with animal influenza viruses is rare, as they do not transmit easily to or among humans.[8] However, avian and swine influenza viruses in particular possess high zoonotic potential,[9] and these occasionally recombine with human strains of the flu and can cause pandemics such as the 2009 swine flu.[10] Zoonoses can be caused by a range of disease pathogens such as emergent viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites; of 1,415 pathogens known to infect humans, 61% were zoonotic.[11] Most human diseases originated in non-humans; however, only diseases that routinely involve non-human to human transmission, such as rabies, are considered direct zoonoses.[12]

Zoonoses have different modes of transmission. In direct zoonosis the disease is directly transmitted between non-humans and humans through the air (influenza), bites and saliva (rabies),[13] faecal-oral transmission or through contaminated food. Transmission can also occur via an intermediate species (referred to as a vector), which carry the disease pathogen without getting sick. The term is from Ancient Greek ζῷον (zoon) 'animal' and νόσος (nosos) 'sickness'.

Host genetics plays an important role in determining which non-human viruses will be able to make copies of themselves in the human body. Dangerous non-human viruses are those that require few mutations to begin replicating themselves in human cells. These viruses are dangerous since the required combinations of mutations might randomly arise in the natural reservoir.[14]

Causes

[edit]The emergence of zoonotic diseases originated with the domestication of animals.[15][16] Zoonotic transmission can occur in any context in which there is contact with or consumption of animals, animal products, or animal derivatives. This can occur in a companionistic (pets)[16], economic (farming, trade, butchering, etc.), predatory (hunting, butchering, or consuming wild game), or research context.[17][18]

Recently, there has been a rise in frequency of appearance of new zoonotic diseases. "Approximately 1.67 million undescribed viruses are thought to exist in mammals and birds, up to half of which are estimated to have the potential to spill over into humans", says a study[19] led by researchers at the University of California, Davis. According to a report from the United Nations Environment Programme and International Livestock Research Institute a large part of the causes are environmental like climate change, unsustainable agriculture, exploitation of wildlife, and land use change. Others are linked to changes in human society such as an increase in mobility. The organizations propose a set of measures to stop the rise.[20][21]

Contamination of food or water supply

[edit]Foodborne zoonotic diseases are caused by a variety of pathogens that can affect both humans and animals. The most significant zoonotic pathogens causing foodborne diseases are:

Bacterial pathogens

[edit]Escherichia coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Caliciviridae, and Salmonella.[22][23][24]

Viral pathogens

[edit]- Hepatitis E: Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is primarily transmitted through pork products, especially in developing countries with limited sanitation. The infection can lead to acute liver disease and is particularly dangerous for pregnant women.[25]

- Norovirus: Often found in contaminated shellfish and fresh produce, norovirus is a leading cause of foodborne illness globally. It spreads easily and causes symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain.[26]

Parasitic pathogens

[edit]- Toxoplasma gondii: This parasite is commonly found in undercooked meat, especially pork and lamb, and can cause toxoplasmosis. While typically mild, toxoplasmosis can be severe in immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women, potentially leading to complications.[27]

- Trichinella spp. is transmitted through undercooked pork and wild game, causing trichinellosis. Symptoms range from mild gastrointestinal distress to severe muscle pain and, in rare cases, can be fatal.[28]

Farming, ranching and animal husbandry

[edit]Contact with farm animals can lead to disease in farmers or others that come into contact with infected farm animals. Glanders primarily affects those who work closely with horses and donkeys. Close contact with cattle can lead to cutaneous anthrax infection, whereas inhalation anthrax infection is more common for workers in slaughterhouses, tanneries, and wool mills.[29] Close contact with sheep who have recently given birth can lead to infection with the bacterium Chlamydia psittaci, causing chlamydiosis (and enzootic abortion in pregnant women), as well as increase the risk of Q fever, toxoplasmosis, and listeriosis, in the pregnant or otherwise immunocompromised. Echinococcosis is caused by a tapeworm, which can spread from infected sheep by food or water contaminated by feces or wool. Avian influenza is common in chickens, and, while it is rare in humans, the main public health worry is that a strain of avian influenza will recombine with a human influenza virus and cause a pandemic like the 1918 Spanish flu.[30] In 2017, free-range chickens in the UK were temporarily ordered to remain inside due to the threat of avian influenza.[31] Cattle are an important reservoir of cryptosporidiosis,[32] which mainly affects the immunocompromised. Reports have shown mink can also become infected.[33] In Western countries, hepatitis E burden is largely dependent on exposure to animal products, and pork is a significant source of infection, in this respect.[25] Similarly, the human coronavirus OC43, the main cause of the common cold, can use the pig as a zoonotic reservoir,[34] constantly reinfecting the human population.

Veterinarians are exposed to unique occupational hazards when it comes to zoonotic disease. In the US, studies have highlighted an increased risk of injuries and lack of veterinary awareness of these hazards. Research has proved the importance for continued clinical veterinarian education on occupational risks associated with musculoskeletal injuries, animal bites, needle-sticks, and cuts.[35]

A July 2020 report by the United Nations Environment Programme stated that the increase in zoonotic pandemics is directly attributable to anthropogenic destruction of nature and the increased global demand for meat and that the industrial farming of pigs and chickens in particular will be a primary risk factor for the spillover of zoonotic diseases in the future.[36] Habitat loss of viral reservoir species has been identified as a significant source in at least one spillover event.[37]

Wildlife trade or animal attacks

[edit]The wildlife trade may increase spillover risk because it directly increases the number of interactions across animal species, sometimes in small spaces.[38] The origin of the COVID-19 pandemic[39][40] is traced to the wet markets in China.[41][42][43][44]

Zoonotic disease emergence is demonstrably linked to the consumption of wildlife meat, exacerbated by human encroachment into natural habitats and amplified by the unsanitary conditions of wildlife markets.[45][46] These markets, where diverse species converge, facilitate the mixing and transmission of pathogens, including those responsible for outbreaks of HIV-1,[47] Ebola,[48] and mpox,[49] and potentially even the COVID-19 pandemic.[50] Notably, small mammals often harbor a vast array of zoonotic bacteria and viruses,[51] yet endemic bacterial transmission among wildlife remains largely unexplored. Therefore, accurately determining the pathogenic landscape of traded wildlife is crucial for guiding effective measures to combat zoonotic diseases and documenting the societal and environmental costs associated with this practice.

Insect vectors

[edit]- African sleeping sickness

- Dirofilariasis

- Eastern equine encephalitis

- Japanese encephalitis

- Saint Louis encephalitis

- Scrub typhus

- Tularemia

- Venezuelan equine encephalitis

- West Nile fever

- Western equine encephalitis

- Zika fever

Pets

[edit]Pets can transmit a number of diseases. Dogs and cats are routinely vaccinated against rabies. Pets can also transmit ringworm and Giardia, which are endemic in both animal and human populations. Toxoplasmosis is a common infection of cats; in humans it is a mild disease although it can be dangerous to pregnant women.[52] Dirofilariasis is caused by Dirofilaria immitis through mosquitoes infected by mammals like dogs and cats. Cat-scratch disease is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana, which are transmitted by fleas that are endemic to cats. Toxocariasis is the infection of humans by any of species of roundworm, including species specific to dogs (Toxocara canis) or cats (Toxocara cati). Cryptosporidiosis can be spread to humans from pet lizards, such as the leopard gecko. Encephalitozoon cuniculi is a microsporidial parasite carried by many mammals, including rabbits, and is an important opportunistic pathogen in people immunocompromised by HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, or CD4+ T-lymphocyte deficiency.[53]

Pets may also serve as a reservoir of viral disease and contribute to the chronic presence of certain viral diseases in the human population. For instance, approximately 20% of domestic dogs, cats, and horses carry anti-hepatitis E virus antibodies and thus these animals probably contribute to human hepatitis E burden as well.[54] For non-vulnerable populations (e.g., people who are not immunocompromised) the associated disease burden is, however, small.[55][56] Furthermore, the trade of non-domestic animals such as wild animals as pets can also increase the risk of zoonosis spread.[57][58]

Bats are frequently unjustly portrayed as the primary instigators of the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic; nevertheless, the true origins of this and other zoonotic spillover occurrences should be attributed to human environmental impacts, especially the proliferation of pets.[16] For example, bat predation by cats poses a significant danger to biodiversity conservation and carries zoonotic consequences that must be acknowledged.[16]

Exhibition

[edit]Outbreaks of zoonoses have been traced to human interaction with, and exposure to, other animals at fairs, live animal markets,[59] petting zoos, and other settings. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an updated list of recommendations for preventing zoonosis transmission in public settings.[60] The recommendations, developed in conjunction with the National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians,[61] include educational responsibilities of venue operators, limiting public animal contact, and animal care and management.

Hunting and bushmeat

[edit]Hunting involves humans tracking, chasing, and capturing wild animals, primarily for food or materials like fur. However, other reasons like pest control or managing wildlife populations can also exist. Transmission of zoonotic diseases, those leaping from animals to humans, can occur through various routes: direct physical contact, airborne droplets or particles, bites or vector transport by insects, oral ingestion, or even contact with contaminated environments.[62] Wildlife activities like hunting and trade bring humans closer to dangerous zoonotic pathogens, threatening global health.[63]

According to the Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) hunting and consuming wild animal meat ("bushmeat") in regions like Africa can expose people to infectious diseases due to the types of animals involved, like bats and primates. Unfortunately, common preservation methods like smoking or drying aren't enough to eliminate these risks.[64] Although bushmeat provides protein and income for many, the practice is intricately linked to numerous emerging infectious diseases like Ebola, HIV, and SARS, raising critical public health concerns.[63]

A review published in 2022 found evidence that zoonotic spillover linked to wildmeat consumption has been reported across all continents.[65]

Deforestation, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation

[edit]Kate Jones, Chair of Ecology and Biodiversity at University College London, says zoonotic diseases are increasingly linked to environmental change and human behavior. The disruption of pristine forests driven by logging, mining, road building through remote places, rapid urbanization, and population growth is bringing people into closer contact with animal species they may never have been near before. The resulting transmission of disease from wildlife to humans, she says, is now "a hidden cost of human economic development".[66] In a guest article, published by IPBES, President of the EcoHealth Alliance and zoologist Peter Daszak, along with three co-chairs of the 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Josef Settele, Sandra Díaz, and Eduardo Brondizio, wrote that "rampant deforestation, uncontrolled expansion of agriculture, intensive farming, mining and infrastructure development, as well as the exploitation of wild species have created a 'perfect storm' for the spillover of diseases from wildlife to people."[67]

Joshua Moon, Clare Wenham, and Sophie Harman said that there is evidence that decreased biodiversity has an effect on the diversity of hosts and frequency of human-animal interactions with potential for pathogenic spillover.[68]

An April 2020 study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society's Part B journal, found that increased virus spillover events from animals to humans can be linked to biodiversity loss and environmental degradation, as humans further encroach on wildlands to engage in agriculture, hunting, and resource extraction they become exposed to pathogens which normally would remain in these areas. Such spillover events have been tripling every decade since 1980.[69] An August 2020 study, published in Nature, concludes that the anthropogenic destruction of ecosystems for the purpose of expanding agriculture and human settlements reduces biodiversity and allows for smaller animals such as bats and rats, which are more adaptable to human pressures and also carry the most zoonotic diseases, to proliferate. This in turn can result in more pandemics.[70]

In October 2020, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published its report on the 'era of pandemics' by 22 experts in a variety of fields and concluded that anthropogenic destruction of biodiversity is paving the way to the pandemic era and could result in as many as 850,000 viruses being transmitted from animals – in particular birds and mammals – to humans. The increased pressure on ecosystems is being driven by the "exponential rise" in consumption and trade of commodities such as meat, palm oil, and metals, largely facilitated by developed nations, and by a growing human population. According to Peter Daszak, the chair of the group who produced the report, "there is no great mystery about the cause of the Covid-19 pandemic, or of any modern pandemic. The same human activities that drive climate change and biodiversity loss also drive pandemic risk through their impacts on our environment."[71][72][73]

Climate change

[edit]According to a report from the United Nations Environment Programme and International Livestock Research Institute, entitled "Preventing the next pandemic – Zoonotic diseases and how to break the chain of transmission", climate change is one of the 7 human-related causes of the increase in the number of zoonotic diseases.[20][21] The University of Sydney issued a study, in March 2021, that examines factors increasing the likelihood of epidemics and pandemics like the COVID-19 pandemic. The researchers found that "pressure on ecosystems, climate change and economic development are key factors" in doing so. More zoonotic diseases were found in high-income countries.[74]

A 2022 study dedicated to the link between climate change and zoonosis found a strong link between climate change and the epidemic emergence in the last 15 years, as it caused a massive migration of species to new areas, and consequently contact between species which do not normally come in contact with one another. Even in a scenario with weak climatic changes, there will be 15,000 spillover of viruses to new hosts in the next decades. The areas with the most possibilities for spillover are the mountainous tropical regions of Africa and southeast Asia. Southeast Asia is especially vulnerable as it has a large number of bat species that generally do not mix, but could easily if climate change forced them to begin migrating.[75]

A 2021 study found possible links between climate change and transmission of COVID-19 through bats. The authors suggest that climate-driven changes in the distribution and robustness of bat species harboring coronaviruses may have occurred in eastern Asian hotspots (southern China, Myanmar, and Laos), constituting a driver behind the evolution and spread of the virus.[76][77]

Secondary transmission

[edit]Zoonotic diseases contribute significantly to the burdened public health system as vulnerable groups such the elderly, children, childbearing women and immune-compromised individuals are at risk.[citation needed] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), any disease or infection that is primarily "naturally" transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans or from humans to animals is classified as a zoonosis.[78] Factors such as climate change, urbanization, animal migration and trade, travel and tourism, vector biology, anthropogenic factors, and natural factors have greatly influenced the emergence, re-emergence, distribution, and patterns of zoonoses.[78]

Zoonotic diseases generally refer to diseases of animal origin in which direct or vector mediated animal-to-human transmission is the usual source of human infection. Animal populations are the principal reservoir of the pathogen and horizontal infection in humans is rare. A few examples in this category include lyssavirus infections, Lyme borreliosis, plague, tularemia, leptospirosis, ehrlichiosis, Nipah virus, West Nile virus, and hantavirus infections.[79] Secondary transmission encompasses a category of diseases of animal origin in which the actual transmission to humans is a rare event but, once it has occurred, human-to-human transmission maintains the infection cycle for some period of time. Some examples include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), certain influenza A strains, Ebola virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).[79]

One example is Ebola, which is spread by direct transmission to humans from handling bushmeat (wild animals hunted for food) and contact with infected bats or close contact with infected animals, including chimpanzees, fruit bats, and forest antelope. Secondary transmission also occurs from human to human by direct contact with blood, bodily fluids, or skin of patients with or who died of Ebola virus disease.[80] Some examples of pathogens with this pattern of secondary transmission are human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, influenza A, Ebola virus, and SARS. Recent infections of these emerging and re-emerging zoonotic infections have occurred as a results of many ecological and sociological changes globally.[79]

History

[edit]During most of human prehistory groups of hunter-gatherers were probably very small. Such groups probably made contact with other such bands only rarely. Such isolation would have caused epidemic diseases to be restricted to any given local population, because propagation and expansion of epidemics depend on frequent contact with other individuals who have not yet developed an adequate immune response.[81] To persist in such a population, a pathogen either had to be a chronic infection, staying present and potentially infectious in the infected host for long periods, or it had to have other additional species as reservoir where it can maintain itself until further susceptible hosts are contacted and infected.[82][83] In fact, for many "human" diseases, the human is actually better viewed as an accidental or incidental victim and a dead-end host. Examples include rabies, anthrax, tularemia, and West Nile fever. Thus, much of human exposure to infectious disease has been zoonotic.[84]

Many diseases, even epidemic ones, have zoonotic origin and measles, smallpox, influenza, HIV, and diphtheria are particular examples.[85][86] Various forms of the common cold and tuberculosis also are adaptations of strains originating in other species.[87][88] Some experts have suggested that all human viral infections were originally zoonotic.[89]

Zoonoses are of interest because they are often previously unrecognized diseases or have increased virulence in populations lacking immunity. The West Nile virus first appeared in the United States in 1999, in the New York City area. Bubonic plague is a zoonotic disease,[90] as are salmonellosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Lyme disease.

A major factor contributing to the appearance of new zoonotic pathogens in human populations is increased contact between humans and wildlife.[91] This can be caused either by encroachment of human activity into wilderness areas or by movement of wild animals into areas of human activity. An example of this is the outbreak of Nipah virus in peninsular Malaysia, in 1999, when intensive pig farming began within the habitat of infected fruit bats.[92] The unidentified infection of these pigs amplified the force of infection, transmitting the virus to farmers, and eventually causing 105 human deaths.[93]

Similarly, in recent times avian influenza and West Nile virus have spilled over into human populations probably due to interactions between the carrier host and domestic animals.[94] Highly mobile animals, such as bats and birds, may present a greater risk of zoonotic transmission than other animals due to the ease with which they can move into areas of human habitation.

Because they depend on the human host[95] for part of their life-cycle, diseases such as African schistosomiasis, river blindness, and elephantiasis are not defined as zoonotic, even though they may depend on transmission by insects or other vectors.[citation needed]

Use in vaccines

[edit]The first vaccine against smallpox by Edward Jenner in 1800 was by infection of a zoonotic bovine virus which caused a disease called cowpox.[96] Jenner had noticed that milkmaids were resistant to smallpox. Milkmaids contracted a milder version of the disease from infected cows that conferred cross immunity to the human disease. Jenner abstracted an infectious preparation of 'cowpox' and subsequently used it to inoculate persons against smallpox. As a result of vaccination, smallpox has been eradicated globally, and mass inoculation against this disease ceased in 1981.[97] There are a variety of vaccine types, including traditional inactivated pathogen vaccines, subunit vaccines, live attenuated vaccines. There are also new vaccine technologies such as viral vector vaccines and DNA/RNA vaccines, which include many of the COVID-19 vaccines.[98]

Lists of diseases

[edit]See also

[edit]- Animal welfare#Animal welfare organizations – Well-being of non-human animals

- Conservation medicine

- Cross-species transmission – Transmission of a pathogen between different species

- Emerging infectious disease – Infectious disease of emerging pathogen, often novel in its outbreak range or transmission mode

- Foodborne illness – Illness from eating spoiled or contaminated food

- Spillover infection – Occurs when a reservoir population causes an epidemic in a novel host population

- Wildlife disease

- Veterinary medicine – Branch of medicine for non-human animals

- Wildlife smuggling and zoonoses – Health risks associated with the trade in exotic wildlife

- List of zoonotic primate viruses

References

[edit]- ^ a b "zoonosis". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Messenger AM, Barnes AN, Gray GC (2014). "Reverse zoonotic disease transmission (zooanthroponosis): a systematic review of seldom-documented human biological threats to animals". PLOS ONE. 9 (2) e89055. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...989055M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089055. PMC 3938448. PMID 24586500.

- ^ WHO. "Zoonoses". Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ "A glimpse into Canada's highest containment laboratory for animal health: The National Centre for Foreign Animal Diseases". science.gc.ca. Government of Canada. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

Zoonoses are infectious diseases which jump from a non-human host or reservoir into humans.

- ^ Sharp PM, Hahn BH (September 2011). "Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 1 (1) a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. PMC 3234451. PMID 22229120.

- ^ Faria NR, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Baele G, Bedford T, Ward MJ, et al. (October 2014). "HIV epidemiology. The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations". Science. 346 (6205): 56–61. Bibcode:2014Sci...346...56F. doi:10.1126/science.1256739. PMC 4254776. PMID 25278604.

- ^ Marx PA, Alcabes PG, Drucker E (June 2001). "Serial human passage of simian immunodeficiency virus by unsterile injections and the emergence of epidemic human immunodeficiency virus in Africa". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 356 (1410): 911–920. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.0867. PMC 1088484. PMID 11405938.

- ^ World Health Organization (3 October 2023). "Influenza (Avian and other zoonotic)". who.int. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Abdelwhab, EM; Mettenleiter, TC (April 2023). "Zoonotic Animal Influenza Virus and Potential Mixing Vessel Hosts". Viruses. 15 (4): 980. doi:10.3390/v15040980. PMC 10145017. PMID 37112960.

- ^ Scotch M, Brownstein JS, Vegso S, Galusha D, Rabinowitz P (September 2011). "Human vs. animal outbreaks of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic". EcoHealth. 8 (3): 376–380. doi:10.1007/s10393-011-0706-x. PMC 3246131. PMID 21912985.

- ^ Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse ME (July 2001). "Risk factors for human disease emergence". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 356 (1411): 983–989. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.0888. PMC 1088493. PMID 11516376.

- ^ Marx PA, Apetrei C, Drucker E (October 2004). "AIDS as a zoonosis? Confusion over the origin of the virus and the origin of the epidemics". Journal of Medical Primatology. 33 (5–6): 220–226. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00078.x. PMID 15525322.

- ^ "Zoonosis". Medical Dictionary. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ Warren CJ, Sawyer SL (April 2019). "How host genetics dictates successful viral zoonosis". PLOS Biology. 17 (4) e3000217. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000217. PMC 6474636. PMID 31002666.

- ^ Nibert D (2013). Animal Oppression and Human Violence: Domesecration, Capitalism, and Global Conflict. Columbia University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-231-15189-4.

- ^ a b c d Salinas-Ramos, Valeria B.; Mori, Emiliano; Bosso, Luciano; Ancillotto, Leonardo; Russo, Danilo (5 March 2021). "Zoonotic Risk: One More Good Reason Why Cats Should Be Kept Away from Bats". Pathogens. 10 (3): 304. doi:10.3390/pathogens10030304. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 8002059. PMID 33807760.

- ^ CDC (16 May 2024). "About Zoonotic Diseases". One Health. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- ^ "Zoonoses". www.who.int. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- ^ Grange ZL, Goldstein T, Johnson CK, Anthony S, Gilardi K, Daszak P, et al. (April 2021). "Ranking the risk of animal-to-human spillover for newly discovered viruses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (15) e2002324118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11802324G. doi:10.1073/pnas.2002324118. PMC 8053939. PMID 33822740.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus: Fear over rise in animal-to-human diseases". BBC. 6 July 2020. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Preventing the next pandemic – Zoonotic diseases and how to break the chain of transmission". United Nations Environmental Programme. United Nations. 15 May 2020. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Humphrey T, O'Brien S, Madsen M (July 2007). "Campylobacters as zoonotic pathogens: a food production perspective". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 117 (3): 237–257. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.01.006. PMID 17368847.

- ^ Cloeckaert A (June 2006). "Introduction: emerging antimicrobial resistance mechanisms in the zoonotic foodborne pathogens Salmonella and Campylobacter". Microbes and Infection. 8 (7): 1889–1890. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.12.024. PMID 16714136.

- ^ Murphy FA (1999). "The threat posed by the global emergence of livestock, food-borne, and zoonotic pathogens". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 894 (1): 20–27. Bibcode:1999NYASA.894...20M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08039.x. PMID 10681965. S2CID 13384121.

- ^ a b Li TC, Chijiwa K, Sera N, Ishibashi T, Etoh Y, Shinohara Y, et al. (December 2005). "Hepatitis E virus transmission from wild boar meat". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1958–1960. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100350. PMC 8606544. PMID 16485490.

- ^ Ushijima, Hiroshi; Fujimoto, Tsuguto; Müller, Werner EG; Hayakawa, Satoshi (2014). "Norovirus and Foodborne Disease: A Review". Food Safety. 2 (3): 37–54. doi:10.14252/foodsafetyfscj.2014027.

- ^ Marín-García, Pablo-Jesús; Planas, Nuria; Llobat, Lola (January 2022). "Toxoplasma gondii in Foods: Prevalence, Control, and Safety". Foods. 11 (16): 2542. doi:10.3390/foods11162542. ISSN 2304-8158. PMC 9407268. PMID 36010541.

- ^ Noeckler, Karsten; Pozio, Edoardo; van der Giessen, Joke; Hill, Dolores E.; Gamble, H. Ray (1 March 2019). "International Commission on Trichinellosis: Recommendations on post-harvest control of Trichinella in food animals". Food and Waterborne Parasitology. 14 e00041. doi:10.1016/j.fawpar.2019.e00041. ISSN 2405-6766. PMC 7033995. PMID 32095607.

- ^ "Inhalation Anthrax". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Peiris, J. S. Malik; de Jong, Menno D.; Guan, Yi (April 2007). "Avian Influenza Virus (H5N1): a Threat to Human Health". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (2): 243–267. doi:10.1128/cmr.00037-06. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 1865597. PMID 17428885.

- ^ "Avian flu: Poultry to be allowed outside under new rules". BBC News. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Lassen B, Ståhl M, Enemark HL (June 2014). "Cryptosporidiosis - an occupational risk and a disregarded disease in Estonia". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 56 (1): 36. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-56-36. PMC 4089559. PMID 24902957.

- ^ "Mink found to have coronavirus on two Dutch farms – ministry". Reuters. 26 April 2020. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Xu G, Qiao Z, Schraauwen R, Avan A, Peppelenbosch MP, Bijvelds MJ, Jiang S, Li P (April 2024). "Evidence for cross-species transmission of human coronavirus OC43 through bioinformatics and modeling infections in porcine intestinal organoids". Veterinary Microbiology. 293 110101. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2024.110101. PMID 38718529.

- ^ Rood KA, Pate ML (January 2019). "Assessment of Musculoskeletal Injuries Associated with Palpation, Infection Control Practices, and Zoonotic Disease Risks among Utah Clinical Veterinarians". Journal of Agromedicine. 24 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2018.1536574. PMID 30362924. S2CID 53092026.

- ^ Carrington D (6 July 2020). "Coronavirus: world treating symptoms, not cause of pandemics, says UN". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ von Csefalvay, Chris (2023), "Host-vector and multihost systems", Computational Modeling of Infectious Disease, Elsevier, pp. 121–149, doi:10.1016/b978-0-32-395389-4.00013-x, ISBN 978-0-323-95389-4, retrieved 6 March 2023

- ^ Glidden CK, Nova N, Kain MP, Lagerstrom KM, Skinner EB, Mandle L, et al. (October 2021). "Human-mediated impacts on biodiversity and the consequences for zoonotic disease spillover". Current Biology. 31 (19): R1342 – R1361. Bibcode:2021CBio...31R1342G. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.070. PMC 9255562. PMID 34637744. S2CID 238588772.

- ^ You M (October 2020). "Changes of China's regulatory regime on commercial artificial breeding of terrestrial wildlife in time of COVID-19 outbreak and impacts on the future". Biological Conservation. 250 (3). Oxford University Press: 108756. doi:10.1093/bjc/azaa084. PMC 7953978. PMID 32863392.

- ^ Blattner C, Coulter K, Wadiwel D, Kasprzycka E (2021). "Covid-19 and Capital: Labour Studies and Nonhuman Animals – A Roundtable Dialogue". Animal Studies Journal. 10 (1). University of Wollongong: 240–272. doi:10.14453/asj.v10i1.10. ISSN 2201-3008. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Sun J, He WT, Wang L, Lai A, Ji X, Zhai X, et al. (May 2020). "COVID-19: Epidemiology, Evolution, and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 26 (5): 483–495. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2020.02.008. PMC 7118693. PMID 32359479.

- ^ "WHO Points To Wildlife Farms In Southern China As Likely Source Of Pandemic". NPR. 15 March 2021.

- ^ Maxmen A (April 2021). "WHO report into COVID pandemic origins zeroes in on animal markets, not labs". Nature. 592 (7853): 173–174. Bibcode:2021Natur.592..173M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00865-8. PMID 33785930. S2CID 232429241.

- ^ Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun; Yu, Ting; Xia, Jiaan; Wei, Yuan; Wu, Wenjuan (15 February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- ^ Karesh, William B.; Cook, Robert A.; Bennett, Elizabeth L.; Newcomb, James (July 2005). "Wildlife trade and global disease emergence". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (7): 1000–1002. doi:10.3201/eid1107.050194. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 3371803. PMID 16022772.

- ^ "Zoonotic Pathogens in Wildlife Traded in Markets for Human Consumption, Laos". cdc.gov. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ^ Hahn, B. H.; Shaw, G. M.; De Cock, K. M.; Sharp, P. M. (28 January 2000). "AIDS as a zoonosis: scientific and public health implications". Science. 287 (5453): 607–614. Bibcode:2000Sci...287..607H. doi:10.1126/science.287.5453.607. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10649986.

- ^ Leroy, Eric M.; Rouquet, Pierre; Formenty, Pierre; Souquière, Sandrine; Kilbourne, Annelisa; Froment, Jean-Marc; Bermejo, Magdalena; Smit, Sheilag; Karesh, William; Swanepoel, Robert; Zaki, Sherif R.; Rollin, Pierre E. (16 January 2004). "Multiple Ebola virus transmission events and rapid decline of central African wildlife". Science. 303 (5656): 387–390. Bibcode:2004Sci...303..387L. doi:10.1126/science.1092528. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 14726594. S2CID 43305484.

- ^ Reed, Kurt D.; Melski, John W.; Graham, Mary Beth; Regnery, Russell L.; Sotir, Mark J.; Wegner, Mark V.; Kazmierczak, James J.; Stratman, Erik J.; Li, Yu; Fairley, Janet A.; Swain, Geoffrey R.; Olson, Victoria A.; Sargent, Elizabeth K.; Kehl, Sue C.; Frace, Michael A. (22 January 2004). "The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere". The New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (4): 342–350. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032299. ISSN 1533-4406. PMID 14736926.

- ^ Li, Xiaojun; Giorgi, Elena E.; Marichannegowda, Manukumar Honnayakanahalli; Foley, Brian; Xiao, Chuan; Kong, Xiang-Peng; Chen, Yue; Gnanakaran, S.; Korber, Bette; Gao, Feng (July 2020). "Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 through recombination and strong purifying selection". Science Advances. 6 (27) eabb9153. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.9153L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb9153. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7458444. PMID 32937441.

- ^ Mills, J. N.; Childs, J. E. (1998). "Ecologic studies of rodent reservoirs: their relevance for human health". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 4 (4): 529–537. doi:10.3201/eid0404.980403. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2640244. PMID 9866729.

- ^ Prevention, CDC – Centers for Disease Control and. "Toxoplasmosis – General Information – Pregnant Women". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Weese JS (2011). Companion animal zoonoses. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 282–84. ISBN 978-0-8138-1964-8.

- ^ Li Y, Qu C, Spee B, Zhang R, Penning LC, de Man RA, et al. (2020). "Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence in pets in the Netherlands and the permissiveness of canine liver cells to the infection". Irish Veterinary Journal. 73 6. doi:10.1186/s13620-020-00158-y. PMC 7119158. PMID 32266057.

- ^ "Hepatitis E". www.who.int. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Zahmanova, Gergana; Takova, Katerina; Tonova, Valeria; Koynarski, Tsvetoslav; Lukov, Laura L.; Minkov, Ivan; Pishmisheva, Maria; Kotsev, Stanislav; Tsachev, Ilia; Baymakova, Magdalena; Andonov, Anton P. (16 July 2023). "The Re-Emergence of Hepatitis E Virus in Europe and Vaccine Development". Viruses. 15 (7): 1558. doi:10.3390/v15071558. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 10383931. PMID 37515244.

- ^ D'Cruze, Neil; Green, Jennah; Elwin, Angie; Schmidt-Burbach, Jan (December 2020). "Trading Tactics: Time to Rethink the Global Trade in Wildlife". Animals. 10 (12): 2456. doi:10.3390/ani10122456. ISSN 2076-2615. PMC 7767496. PMID 33371486.

- ^ Aguirre, A. Alonso; Catherina, Richard; Frye, Hailey; Shelley, Louise (September 2020). "Illicit Wildlife Trade, Wet Markets, and COVID-19: Preventing Future Pandemics". World Medical & Health Policy. 12 (3): 256–265. doi:10.1002/wmh3.348. ISSN 1948-4682. PMC 7362142. PMID 32837772.

- ^ Chomel BB, Belotto A, Meslin FX (January 2007). "Wildlife, exotic pets, and emerging zoonoses". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (1): 6–11. doi:10.3201/eid1301.060480. PMC 2725831. PMID 17370509.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005). "Compendium of Measures To Prevent Disease Associated with Animals in Public Settings, 2005: National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians, Inc. (NASPHV)" (PDF). MMWR. 54 (RR–4): inclusive page numbers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "NASPHV – National Association of Public Health Veterinarians". www.nasphv.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ^ Murray, Kris A.; Allen, Toph; Loh, Elizabeth; Machalaba, Catherine; Daszak, Peter (2016), Jay-Russell, Michele; Doyle, Michael P. (eds.), "Emerging Viral Zoonoses from Wildlife Associated with Animal-Based Food Systems: Risks and Opportunities", Food Safety Risks from Wildlife: Challenges in Agriculture, Conservation, and Public Health, Food Microbiology and Food Safety, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 31–57, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24442-6_2, ISBN 978-3-319-24442-6

- ^ a b Kurpiers, Laura A.; Schulte-Herbrüggen, Björn; Ejotre, Imran; Reeder, DeeAnn M. (21 September 2015). "Bushmeat and Emerging Infectious Diseases: Lessons from Africa". Problematic Wildlife. pp. 507–551. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22246-2_24. ISBN 978-3-319-22245-5. PMC 7123567.

- ^ "Bushmeat Importation Policies | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 21 November 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Milbank, Charlotte; Vira, Bhaskar (May 2022). "Wildmeat consumption and zoonotic spillover: contextualising disease emergence and policy responses". The Lancet. Planetary Health. 6 (5): e439 – e448. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00064-X. ISSN 2542-5196. PMC 9084621. PMID 35550083.

- ^ Vidal J (18 March 2020). "'Tip of the iceberg': is our destruction of nature responsible for Covid-19?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (27 April 2020). "Halt destruction of nature or suffer even worse pandemics, say world's top scientists". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Moon J, Wenham C, Harman S (November 2021). "SAGO has a politics problem, and WHO is ignoring it". BMJ. 375 n2786. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2786. PMID 34772656. S2CID 244041854.

- ^ Shield C (16 April 2020). "Coronavirus Pandemic Linked to Destruction of Wildlife and World's Ecosystems". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (5 August 2020). "Deadly diseases from wildlife thrive when nature is destroyed, study finds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Woolaston K, Fisher JL (29 October 2020). "UN report says up to 850,000 animal viruses could be caught by humans, unless we protect nature". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (29 October 2020). "Protecting nature is vital to escape 'era of pandemics' – report". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Escaping the 'Era of Pandemics': experts warn worse crises to come; offer options to reduce risk". EurekAlert!. 29 October 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Factors that may predict next pandemic". ScienceDaily. University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Yong, Ed (28 April 2022). "We Created the 'Pandemicene'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Beyer RM, Manica A, Mora C (May 2021). "Shifts in global bat diversity suggest a possible role of climate change in the emergence of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2". The Science of the Total Environment. 767 145413. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.76745413B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145413. PMC 7837611. PMID 33558040.

- ^ Bressan D. "Climate Change Could Have Played A Role In The Covid-19 Outbreak". Forbes. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ a b Rahman, Md Tanvir; Sobur, Md Abdus; Islam, Md Saiful; Ievy, Samina; Hossain, Md Jannat; El Zowalaty, Mohamed E.; Rahman, AMM Taufiquer; Ashour, Hossam M. (September 2020). "Zoonotic Diseases: Etiology, Impact, and Control". Microorganisms. 8 (9): 1405. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8091405. ISSN 2076-2607. PMC 7563794. PMID 32932606.

- ^ a b c SCHLUNDT, J.; TOYOFUKU, H.; FISHER, J.R.; ARTOIS, M.; MORNER, T.; TATE, C.M. (1 August 2004). "The role of wildlife in emerging and re-emerging zoonoses". Revue Scientifique et Technique de l'OIE. 23 (2): 485–496. doi:10.20506/rst.23.2.1498. ISSN 0253-1933.

- ^ Rewar, Suresh; Mirdha, Dashrath (8 May 2015). "Transmission of Ebola Virus Disease: An Overview". Annals of Global Health. 80 (6): 444–451. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2015.02.005. ISSN 2214-9996. PMID 25960093.

- ^ "Early Concepts of Disease". sphweb.bumc.bu.edu. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Van Seventer, Jean Maguire; Hochberg, Natasha S. (2017). "Principles of Infectious Diseases:Transmission, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Control". International Encyclopedia of Public Health. pp. 22–39. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803678-5.00516-6. ISBN 978-0-12-803708-9. PMC 7150340.

- ^ Health (US), National Institutes of; Study, Biological Sciences Curriculum (2007). Understanding Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases. National Institutes of Health (US).

- ^ Baum, Stephen G. (2008). "Zoonoses-With Friends Like This, Who Needs Enemies?". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 119: 39–52. ISSN 0065-7778. PMC 2394705. PMID 18596867.

- ^ Weiss, Robin A; Sankaran, Neeraja (18 January 2022). "Emergence of epidemic diseases: zoonoses and other origins". Faculty Reviews. 11: 2. doi:10.12703/r/11-2. ISSN 2732-432X. PMC 8808746. PMID 35156099.

- ^ Wolfe, Nathan D.; Dunavan, Claire Panosian; Diamond, Jared (May 2007). "Origins of major human infectious diseases". Nature. 447 (7142): 279–283. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..279W. doi:10.1038/nature05775. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7095142. PMID 17507975.

- ^ "Common Cold Virus Came From Birds About 200 Years Ago, Study Suggests". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- ^ Holloway, K.L.; Henneberg, R.J.; de Barros Lopes, M.; Henneberg, M. (December 2011). "Evolution of human tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of paleopathological evidence". Homo. 62 (6): 402–458. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2011.10.001. ISSN 0018-442X. PMID 22093291.

- ^ Benatar D (September 2007). "The chickens come home to roost". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (9): 1545–1546. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.090431. PMC 1963309. PMID 17666704.

- ^ Meerburg BG, Singleton GR, Kijlstra A (2009). "Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 35 (3): 221–270. doi:10.1080/10408410902989837. PMID 19548807. S2CID 205694138.

- ^ Daszak P, Cunningham AA, Hyatt AD (February 2001). "Anthropogenic environmental change and the emergence of infectious diseases in wildlife". Acta Tropica. 78 (2): 103–116. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00179-0. PMID 11230820.

- ^ Looi, Lai-Meng; Chua, Kaw-Bing (2007). "Lessons from the Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia". Malaysian Journal of Pathology. 29 (2): 63–67. PMID 19108397.

- ^ Field H, Young P, Yob JM, Mills J, Hall L, Mackenzie J (April 2001). "The natural history of Hendra and Nipah viruses". Microbes and Infection. 3 (4): 307–314. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01384-3. PMID 11334748.

- ^ Fong, I. W. (2017), "Animals and Mechanisms of Disease Transmission", Emerging Zoonoses, Cham: Springer International Publishing: 15–38, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50890-0_2, ISBN 978-3-319-50888-7, PMC 7120673

- ^ Basu, Dr Muktisadhan (16 August 2022). "Zoonotic Diseases and Its Impact on Human Health". Agritech Consultancy Services. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "History of Smallpox | Smallpox | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 21 February 2021. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "The Spread and Eradication of Smallpox | Smallpox | CDC". 19 February 2019.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (4 November 2023). "Different types of COVID-19 vaccines: How they work". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bardosh K (2016). One Health: Science, Politics and Zoonotic Disease in Africa. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-96148-7..

- Crawford D (2018). Deadly Companions: How Microbes Shaped our History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-881544-0.

- Felbab-Brown V (6 October 2020). "Preventing the next zoonotic pandemic". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Greger M (2007). "The human/animal interface: emergence and resurgence of zoonotic infectious diseases". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 33 (4): 243–299. doi:10.1080/10408410701647594. PMID 18033595. S2CID 8940310. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- H. Krauss, A. Weber, M. Appel, B. Enders, A. v. Graevenitz, H. D. Isenberg, H. G. Schiefer, W. Slenczka, H. Zahner: Zoonoses. Infectious Diseases Transmissible from Animals to Humans. 3rd Edition, 456 pages. ASM Press. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C., 2003. ISBN 1-55581-236-8.

- González JG (2010). Infection Risk and Limitation of Fundamental Rights by Animal-To-Human Transplantations. EU, Spanish and German Law with Special Consideration of English Law (in German). Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovac. ISBN 978-3-8300-4712-4.

- Quammen D (2013). Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-34661-9.

External links

[edit]Zoonosis

View on GrokipediaZoonosis is an infectious disease naturally transmitted between vertebrate animals and humans, involving pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, or fungi that originate in animal reservoirs and spill over to human hosts.[1][2][3]

These diseases constitute a major component of human infectious pathology, with over 60% of known infectious diseases in humans being zoonotic and approximately 75% of emerging infectious diseases arising from animal sources.[3][4]

Transmission mechanisms include direct contact with infected animals or their tissues and fluids, indirect exposure through contaminated water, food, or environments, and vector-mediated spread via arthropods like ticks or mosquitoes.[1][5][6]

Key examples encompass rabies, which spreads through animal bites and remains nearly 100% fatal post-symptom onset without prompt intervention; Lyme disease, vectored by Ixodes ticks from rodent reservoirs; and bacterial infections like salmonellosis, often linked to poultry or reptile handling.[7][1]

Zoonotic events are influenced by ecological disruptions such as habitat loss and intensified human-wildlife interfaces, underscoring the need for integrated surveillance across human, animal, and environmental sectors to mitigate spillover risks.[8][9]

Fundamentals

Definition and Scope

Zoonosis refers to an infectious disease or infection that is naturally transmitted between vertebrate animals and humans, with animals typically serving as the primary reservoir or source of the pathogen. These diseases arise when pathogens adapted to animal hosts spillover to humans, often requiring the pathogen to overcome species barriers for successful infection. Zoonotic agents include bacteria (such as Brucella species causing brucellosis), viruses (such as rabies virus), parasites (such as Toxoplasma gondii causing toxoplasmosis), fungi, and prions, though the majority involve bacterial, viral, or parasitic etiologies.[1][3][10] The scope of zoonoses encompasses over 200 recognized diseases worldwide, accounting for approximately 60% of all known human pathogens and 75% of emerging or re-emerging infectious diseases reported since 1940. This prevalence underscores zoonoses as a leading cause of human illness, responsible for an estimated 2.5 billion cases and 2.7 million deaths annually, with disproportionate impacts in regions of high human-animal interface such as rural or agricultural areas. While transmission is unidirectional from animals to humans in classical zoonoses, reverse zoonoses (anthroponoses) where humans infect animals can occur, complicating eradication efforts for shared pathogens like influenza viruses; however, the core focus remains on animal-origin spillovers driven by ecological and behavioral factors.[11][5][3][12] Zoonoses differ from purely human pathogens by their dependence on animal maintenance hosts, often wildlife or domestic species, which sustain the pathogen in nature without human intervention. This ecological dependency expands the scope beyond direct human-animal contact to include vector-borne (e.g., Lyme disease via ticks) and environmental pathways, emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary surveillance across veterinary, medical, and ecological domains to mitigate risks from habitat encroachment or intensified animal husbandry.[2][1]Classification of Zoonotic Agents

Zoonotic agents are classified primarily by their etiological type, encompassing bacteria, viruses, parasites (including protozoa and helminths), fungi, and unconventional agents such as prions.[13] [3] This categorization reflects the diverse biological mechanisms by which these pathogens infect animal reservoirs and transmit to humans.[1] Bacterial agents constitute the most numerous category, surpassing viruses in the count of known zoonoses, followed by helminths, protozoa, and fungi.[14] Bacterial Zoonotic AgentsBacterial zoonoses include pathogens like Brucella species, which cause brucellosis transmitted via contact with infected livestock or unpasteurized dairy products.[5] Salmonella species lead to salmonellosis, often through contaminated food from animal sources such as poultry and reptiles.[1] Other examples encompass Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), Yersinia pestis (plague), Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), and Mycobacterium bovis (bovine tuberculosis).[5] Coxiella burnetii, responsible for Q fever, spreads through inhalation of aerosols from infected animals.[15] These bacteria typically require direct contact, ingestion, or vector mediation for transmission.[7] Viral Zoonotic Agents

Viruses represent a significant category, with rabies virus (Lyssavirus) transmitted via bites from infected mammals, causing nearly 59,000 human deaths annually, predominantly in Africa and Asia.[15] Influenza viruses, including avian and swine strains, facilitate zoonotic spillover, as seen in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic originating from swine.[16] Emerging threats include Ebola virus from bats and primates, West Nile virus via mosquitoes, and coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2, linked to bat reservoirs.[1] [15] Viral agents often exhibit high mutation rates, enabling adaptation across species barriers.[17] Parasitic Zoonotic Agents

Parasites are subdivided into protozoan and helminth categories. Protozoa such as Toxoplasma gondii infect via oocysts from cat feces or undercooked meat, affecting over 40 million people in the U.S. alone.[18] Cryptosporidium species cause waterborne cryptosporidiosis from contaminated animal-derived sources.[19] Helminths include Toxocara species, roundworms from dogs and cats leading to visceral larva migrans, and cestodes like Echinococcus granulosus causing hydatid disease through contact with infected canids.[18] [20] These agents rely on complex life cycles involving intermediate and definitive hosts.[7] Fungal Zoonotic Agents

Fungal zoonoses are less prevalent but include Histoplasma capsulatum, acquired from bat or bird guano, causing histoplasmosis primarily through inhalation.[3] Cryptococcus neoformans from avian excreta can lead to cryptococcosis in immunocompromised individuals.[21] These dimorphic fungi thrive in environmental niches associated with animal habitats, with transmission typically environmental rather than direct.[5] Prion Zoonotic Agents

Prions, proteinaceous infectious particles lacking nucleic acids, represent unconventional agents, as in bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or "mad cow disease") from cattle, which crossed to humans as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease via contaminated beef.[13] Scrapie in sheep and chronic wasting disease in deer pose potential risks, though human transmission remains unconfirmed beyond BSE.[22] Prions propagate by inducing misfolding in host proteins, evading typical immune responses.[17]

Transmission Mechanisms

Direct Animal-to-Human Contact

Direct animal-to-human transmission of zoonotic diseases occurs through physical interactions, including bites, scratches, abrasions, or handling of infected animal tissues, blood, placentas, fetuses, uterine secretions, or other body fluids, which introduce pathogens via breaks in the skin or mucous membranes.[23][24] This mechanism bypasses intermediate vectors or environmental contamination, often posing risks to occupational groups like veterinarians, farmers, abattoir workers, and hunters who frequently manage live or slaughtered animals.[25] Unlike vector-mediated or foodborne routes, direct contact emphasizes immediate proximity and unbarriered exposure, with transmission efficiency depending on pathogen viability in secretions and host susceptibility factors such as wound presence or immune status.[26] Rabies exemplifies direct zoonotic transmission, primarily via the saliva of infected mammals entering through bites or scratches, though mucosal contact with saliva can also suffice. The rabies virus, a lyssavirus, causes nearly 100% fatality once clinical symptoms appear, with global human deaths estimated at around 59,000 annually as of data up to 2015, predominantly from dog bites in endemic regions of Asia and Africa.[24] In the United States, wildlife such as bats, raccoons, skunks, and foxes account for over 90% of the approximately 4,000 reported animal rabies cases yearly, with human exposures often linked to unprovoked bites or handling of infected carcasses.[27] Post-exposure prophylaxis, including wound cleaning and vaccination, prevents progression in exposed individuals, underscoring the causal role of prompt intervention in breaking transmission.[26] Brucellosis, caused by Brucella species bacteria, spreads directly through contact with infected livestock or wildlife during handling, particularly reproductive tissues or aborted materials from cattle, goats, sheep, or pigs. Humans ingest or inhale aerosols minimally in direct scenarios, but skin penetration from cuts during slaughter or birthing is a primary route, leading to chronic fever, joint pain, and organ involvement if untreated.[28] Occupational incidence is elevated among herders and meat processors, with global underreporting masking the burden in endemic pastoral areas.[25] Antibiotic regimens like doxycycline combined with rifampin achieve cure rates over 90% in uncomplicated cases, highlighting the bacterium's intracellular persistence as a key pathogenic factor.[23] Leptospirosis, induced by Leptospira spirochetes, transmits via direct exposure to urine or blood from reservoir animals like rodents, dogs, cattle, or pigs, often penetrating mucous membranes or abraded skin during activities such as cleaning animal enclosures or wading in contaminated farm runoff. While indirect waterborne spread predominates, direct contact cases occur in veterinary settings or rural labor, manifesting as flu-like illness or severe Weil's disease with jaundice and renal failure in 5-10% of symptomatic infections.[29] Annual global incidence exceeds 1 million cases, with higher rates in tropical regions tied to animal density and sanitation deficits.[30] Preventive measures, including protective gloves and rodent control, reduce risk by limiting serovar-specific exposure.[31] Domestic dogs facilitate zoonotic transmission through direct contact with saliva via licks or bites, feces or urine, and infected skin or fur, with risks elevated under conditions of neglected vaccination, inadequate parasite treatment, and poor sanitation.[32] These pathways complement examples like rabies from saliva and leptospirosis from urine, illustrating the role of companion animals in human exposures. Other pathogens like Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) enter via cutaneous contact with spore-laden hides or carcasses, causing localized eschars in 95% of naturally occurring human cases, primarily among tanners and shepherds in endemic zones.[22] These transmissions underscore the causal importance of barrier breaches and pathogen dose, with vaccination and antibiotics mitigating outbreaks in high-risk cohorts.[33]Vector-Mediated Transmission

Vector-mediated transmission occurs when a biological vector, typically an arthropod such as a mosquito, tick, flea, or sandfly, acquires a zoonotic pathogen from an infected animal reservoir during a blood meal, allows the pathogen to replicate or develop within its body, and subsequently transmits it to humans through another bite or contact.[34] This process requires specific vector competence, including the pathogen's ability to survive the vector's immune responses, multiply in tissues like the salivary glands, and be expelled during feeding.[5] Unlike mechanical transmission by contaminated body parts, vector-mediated spread involves an obligatory developmental phase in the vector, enabling efficient dissemination of bacteria, viruses, protozoa, or helminths.[9] Arthropod vectors are the primary agents in zoonotic vector-borne diseases, which account for over 17% of all infectious diseases globally and cause more than 700,000 deaths annually, though many such as malaria maintain primarily human cycles; true zoonoses often involve wildlife or livestock reservoirs.[35] Mosquitoes transmit flaviviruses like West Nile virus (WNV), where birds serve as amplifying hosts; in the United States, WNV caused 1,656 human disease cases in 2025, predominantly neuroinvasive, reflecting seasonal peaks from June to September.[36] In Europe, as of August 2025, eight countries reported 335 locally acquired WNV cases and 19 deaths, with Italy leading due to Culex pipiens vectors bridging avian and human populations.[37] Rift Valley fever, another mosquito-vectored zoonosis from Phlebovirus, cycles in livestock like sheep and cattle, with outbreaks triggered by flooding that boosts Aedes mosquito populations; human infections occur via bites or aerosols during epizootics.[35] Ticks, particularly hard ticks like Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma species, mediate a diverse array of bacterial and viral zoonoses in the Northern Hemisphere, transmitting the highest variety of arthropod-borne pathogens in the United States.[38] Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes from rodent and deer reservoirs, exemplifies this; U.S. surveillance reported an average of 46,115 tickborne disease cases annually from 2019–2022, with Lyme comprising the majority and expanding via climate-driven tick range shifts.[39] Other tick-borne zoonoses include anaplasmosis (Anaplasma phagocytophilum from rodents), ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chaffeensis from white-tailed deer), and Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Rickettsia rickettsii from dogs and small mammals), often co-circulating in endemic areas.[40] Fleas and sandflies facilitate transmission of bacterial and protozoan zoonoses; Yersinia pestis, the plague agent, persists in rodent-flea cycles (e.g., Xenopsylla cheopis vectors from Rattus species), with sporadic human bubonic cases reported globally, including 1–2 dozen annually in the U.S. from prairie dog reservoirs in the Southwest.[5] Leishmaniasis, caused by Leishmania protozoa, involves sandfly vectors (e.g., Phlebotomus) drawing from canine or rodent reservoirs, leading to visceral or cutaneous forms in endemic regions like the Mediterranean and Middle East.[35]| Disease | Primary Vector | Animal Reservoir | Key Regions/Recent Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Nile Virus | Mosquitoes (Culex spp.) | Birds | U.S.: 1,656 cases in 2025; Europe: 335 cases as of Aug 2025[36][37] |

| Lyme Disease | Ticks (Ixodes spp.) | Rodents, deer | U.S.: ~46,000 cases/year (2019–2022 avg.)[39] |

| Plague | Fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) | Rodents | Global sporadic; U.S.: 1–24 cases/year[5] |

| Rift Valley Fever | Mosquitoes (Aedes spp.) | Livestock (sheep, cattle) | Africa/Middle East outbreaks post-flooding[35] |

Foodborne and Waterborne Pathways

Foodborne transmission of zoonotic pathogens typically involves the consumption of animal-derived products contaminated during slaughter, processing, or handling, such as undercooked meat, unpasteurized milk, or eggs harboring bacteria from infected livestock.[3] Common agents include Salmonella enterica, which colonizes the intestines of poultry, cattle, and pigs, leading to approximately 1.35 million cases annually in the United States, with poultry as a primary reservoir.[41] Campylobacter jejuni, prevalent in poultry intestines, causes over 800,000 U.S. illnesses yearly, often from raw or undercooked chicken.[42] Listeria monocytogenes, transmissible via contaminated dairy or processed meats from carrier animals, results in about 1,600 U.S. cases annually, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations with a 20% fatality rate.[43] Parasites like Toxoplasma gondii, shed in cat feces but acquired via undercooked pork or lamb, infect an estimated 11% of Americans, with oocysts persisting in contaminated soil or water used in food production.[5] Waterborne zoonoses arise from ingestion or dermal contact with water sources polluted by urine or feces from infected mammals, reptiles, or birds, facilitating pathogen survival in aquatic environments.[3] Leptospira spp., excreted in rodent or livestock urine, cause leptospirosis, with global incidence exceeding 1 million cases yearly, often linked to flooding or recreational water exposure in endemic areas.[44] Protozoans such as Cryptosporidium parvum, originating from cattle feces, resist chlorination and trigger outbreaks via contaminated drinking water, as seen in the 1993 Milwaukee incident affecting over 400,000 people.[45] Giardia lamblia from wildlife or livestock runoff similarly persists in surface waters, contributing to traveler's diarrhea and water supply contaminations worldwide.[46]| Pathogen | Reservoir Animals | Transmission Vehicle | Annual Global Burden Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella spp. | Poultry, cattle, pigs | Undercooked meat, eggs | 93 million cases[47] |

| Campylobacter spp. | Poultry, cattle | Raw poultry, milk | 96 million cases[42] |

| Leptospira spp. | Rodents, dogs, livestock | Contaminated floodwater, recreational water | >1 million cases[44] |

| Cryptosporidium parvum | Cattle, wildlife | Untreated surface water | Millions in outbreaks[45] |

Aerosol and Environmental Exposure

Aerosol transmission in zoonoses involves the inhalation of pathogen-laden airborne particles generated from infected animals, their bodily fluids, or contaminated materials, often without direct contact. This mechanism is facilitated by activities such as cleaning enclosures, handling birth products, or processing livestock, which aerosolize droplets or dust containing viable microbes. Pathogens like Coxiella burnetii, the agent of Q fever, exemplify this route due to their low infectious dose—reportedly as few as one organism via inhalation—and resilience in aerosols, enabling dispersal over distances up to several kilometers, as observed in outbreaks linked to wind-blown particles from infected farms.[48] [49] Q fever transmission peaks during lambing seasons, with documented cases tied to inhalation from contaminated dust in livestock environments, affecting abattoir workers and nearby residents.[50] Hantaviruses, responsible for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), are transmitted primarily through aerosols created by disturbing dried rodent excreta, urine, or nesting materials in enclosed spaces like cabins or barns. In the Americas, Sin Nombre virus carried by deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) has caused HPS cases with case-fatality rates of 30–40%, where exposure occurs during activities such as sweeping infested areas, generating respirable virus particles that remain viable in air for hours.[51] [52] Environmental factors, including rodent population surges in disturbed habitats, amplify risk by increasing the volume of contaminated aerosols.[53] Avian influenza viruses, particularly highly pathogenic strains like H5N1, can spread via aerosols during poultry slaughter or feather plucking, where infectious droplets exceed viable thresholds for human inhalation, as demonstrated in experimental processing of infected birds yielding higher aerosol loads than from ducks.[54] Psittacosis, caused by Chlamydia psittaci, similarly arises from inhaling feather dust or dried droppings from infected birds, with occupational clusters among bird handlers.[55] These pathogens' environmental persistence—C. burnetii surviving months in soil or dust—extends exposure risks beyond immediate animal proximity, through indirect contact with contaminated fomites or wind-dispersed particles in rural or semi-enclosed settings.[56] [57]Risk Factors

Human Behavioral and Economic Drivers

Human behaviors that increase contact with potential zoonotic reservoirs include hunting wild animals for bushmeat, which has been associated with Ebola virus spillovers through handling infected carcasses, as observed in multiple outbreaks in Central Africa since the 1970s.[9] [58] Consumption of undercooked wildmeat, particularly from primates and bats, facilitates pathogen transmission via oral-fecal routes or direct contact with contaminated tissues, contributing to the origins of HIV from simian immunodeficiency viruses in bushmeat trade chains in early 20th-century Cameroon.[58] Occupational exposure among hunters, farmers, and market vendors heightens risks, as evidenced by Nipah virus transmissions from date palm sap contaminated by bat saliva in Bangladesh, where harvesters' practices enable spillover.[9] Live animal markets, or wet markets, promote cross-species mixing that amplifies spillover potential; for instance, the sale of wildlife alongside domestic animals in Asian markets has been linked to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) emergence in 2002–2003 and suspected for SARS-CoV-2 in 2019, involving high-density confinement of susceptible hosts like civets and raccoon dogs.[59] Cultural practices, such as using animal parts in traditional medicines, further drive handling of exotic species, increasing exposure to pathogens like those causing monkeypox through rodent trade in West Africa.[9] Ecotourism and informal pet trade, including keeping wild animals as exotic pets, introduce additional interfaces, as seen in outbreaks of avian influenza among bird handlers and tourists interacting with poultry in Southeast Asia.[59] Economic pressures exacerbate these behaviors by incentivizing reliance on high-risk activities; poverty in rural Africa compels communities to hunt bushmeat and forage in wildlife habitats due to limited access to domestic protein sources, as documented in Zimbabwe where displaced populations in tsetse-infested areas face elevated trypanosomiasis risks from such livelihoods.[60] In urban slums of developing regions, economic marginalization correlates with poor sanitation and proximity to rodent reservoirs, elevating leptospirosis incidence through behaviors like informal waste handling, with cases surging in Brazilian cities post-floods due to density-dependent exposures.[59] [9] Wildlife trade networks, driven by demand for bushmeat, pets, and traditional remedies, generate economic incentives for capture and transport, involving millions of animals annually across Asia and Africa and facilitating pathogen dispersal, as in the global spread of West Nile virus via migratory birds and human-mediated shipments.[59] Informal economies in pastoral regions, such as Kenya's arid zones where 70% poverty rates limit veterinary services, force livestock-wildlife commingling during droughts, amplifying Rift Valley fever transmission through economic necessities like shared grazing.[60] Large-scale investments in mining and agriculture displace smallholders into disease-prone fringes, undermining sustainable livelihoods and intensifying zoonotic vulnerabilities, as observed in Sierra Leone's rural economies prior to the 2014 Ebola outbreak.[60] These drivers interact with global travel, where economic migration and tourism networks accelerate secondary spread post-spillover, underscoring poverty's role in perpetuating cycles of exposure and limited mitigation capacity.[59]Animal Husbandry and Trade Practices

Intensive animal husbandry practices, particularly in large-scale commercial operations, create conditions conducive to zoonotic pathogen amplification through high stocking densities, limited genetic diversity, and chronic stress on livestock, which can suppress immune responses and promote viral mutations. For instance, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 outbreaks in poultry farms have demonstrated how confined environments enable rapid intra-species spread, with the first US commercial flock confirmation occurring on February 8, 2022, followed by widespread detections across operations housing millions of birds.[61] [62] Similarly, swine production systems have been linked to influenza A reassortment events, as seen in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic origins tracing to intensive pig farming in regions with mixed livestock practices.[62] Global trade in live animals exacerbates these risks by facilitating the movement of infected individuals across borders, often without adequate biosecurity, allowing pathogens to bypass geographic barriers. The United States, as the world's largest importer of wildlife, has imported species harboring potential zoonoses, with studies identifying pathogens in traded animals that could spill over to humans or domestic livestock.[63] Live animal markets, where diverse species are co-mingled under unsanitary conditions, heighten spillover probabilities; SARS-CoV-1 emergence in 2002 was associated with such markets in southern China, where civets and other wildlife were sold alongside humans.[64] [65] Wildlife trade chains, including bushmeat harvesting and exotic pet markets, introduce additional vulnerabilities by stressing wild-caught animals and enabling cross-species transmission prior to human contact. Pathogens like Ebola and monkeypox have been documented in traded wildlife, with illegal trade networks mixing non-native species and amplifying emergence risks through poor quarantine enforcement.[66] [67] While some analyses suggest intensive farming may limit wildlife-livestock interfaces compared to extensive systems, empirical outbreak data indicate that industrial-scale operations still serve as amplifiers once pathogens enter, underscoring the need for enhanced surveillance in both husbandry and trade pathways.[68][62]Environmental and Habitat Alterations

Habitat destruction through deforestation has been associated with heightened zoonotic spillover risks by forcing wildlife into closer proximity with human settlements, thereby increasing opportunities for pathogen transmission. For instance, in tropical regions, rapid forest clearance for agriculture and logging disrupts animal reservoirs, elevating human exposure to viruses like Ebola, where outbreaks have correlated with bushmeat hunting in deforested areas of Central Africa.[59][69] Similarly, studies in South America link deforestation to increased spillover of arboviruses such as yellow fever and Zika, as fragmented habitats concentrate competent hosts like mosquitoes and primates near human populations.[70] Biodiversity loss exacerbates these risks by altering host-pathogen dynamics; reduced species diversity can amplify the prevalence of zoonotic pathogens in remaining wildlife populations, as dominant species become superspreaders. Empirical analyses indicate that habitat fragmentation correlates with higher incidence of diseases like hantavirus and Lyme disease, where loss of natural buffers diminishes dilution effects from diverse ecosystems.[71][8] Agricultural intensification, often involving land conversion, further compounds this by creating interfaces where livestock and wildlife intermingle, facilitating jumps such as Nipah virus from bats to pigs and humans in Malaysia in 1998–1999.[72] Climate-driven habitat shifts, including range expansions of vectors and reservoirs due to warming temperatures, have enabled northward spread of zoonoses like West Nile virus in North America and tick-borne encephalitis in Europe. For example, altered precipitation and temperature patterns have expanded mosquito habitats, correlating with dengue emergence in previously temperate zones.[73][74] Urban expansion into peri-wildland areas similarly heightens exposure; construction and water body alterations in Southeast Asia have been tied to increased human-bat contacts, precursors to coronaviral spillovers.[75] These changes underscore causal pathways where environmental degradation reduces ecological barriers, though direct attribution requires site-specific surveillance to distinguish from other factors like human behavior.[76]Epidemiology

Global Disease Burden

Zoonotic diseases impose a substantial burden on global public health, accounting for an estimated 2.5 billion cases of human illness and 2.7 million deaths annually.[77] More than 60% of known infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic in origin, with approximately 75% of emerging infectious diseases arising from animal reservoirs.[3] This burden is disproportionately borne by low- and middle-income countries, where limited surveillance and control measures exacerbate morbidity and mortality from pathogens such as rabies, which causes around 59,000 deaths per year, primarily in Asia and Africa.[5] Neglected zoonotic diseases (NZDs), including brucellosis, echinococcosis, and leptospirosis, contribute significantly to disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost, with global estimates indicating at least 21 million DALYs annually from selected NZDs alone.[78] These figures underscore the underreported nature of many zoonoses, particularly in resource-poor settings where human-animal interfaces are intensive. Foodborne zoonoses, such as those from Salmonella and Campylobacter, add to the tally, with unsafe food causing 600 million illnesses and 420,000 deaths yearly, a portion attributable to animal sources.[79] Economically, zoonoses generate direct costs exceeding $20 billion over the past decade from treatment and control, alongside indirect losses over $200 billion from livestock depopulation, trade restrictions, and reduced productivity.[80] Recent analyses suggest broader annual global costs ranging from $1 trillion to $6.7 trillion when factoring in pandemic potentials and systemic disruptions, highlighting the need for integrated One Health approaches to mitigate spillover risks.[81] Despite these estimates, data gaps persist due to inconsistent reporting and varying methodologies, potentially understating the true burden in wildlife-dominated ecosystems.[82]Surveillance Methods and Challenges