Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

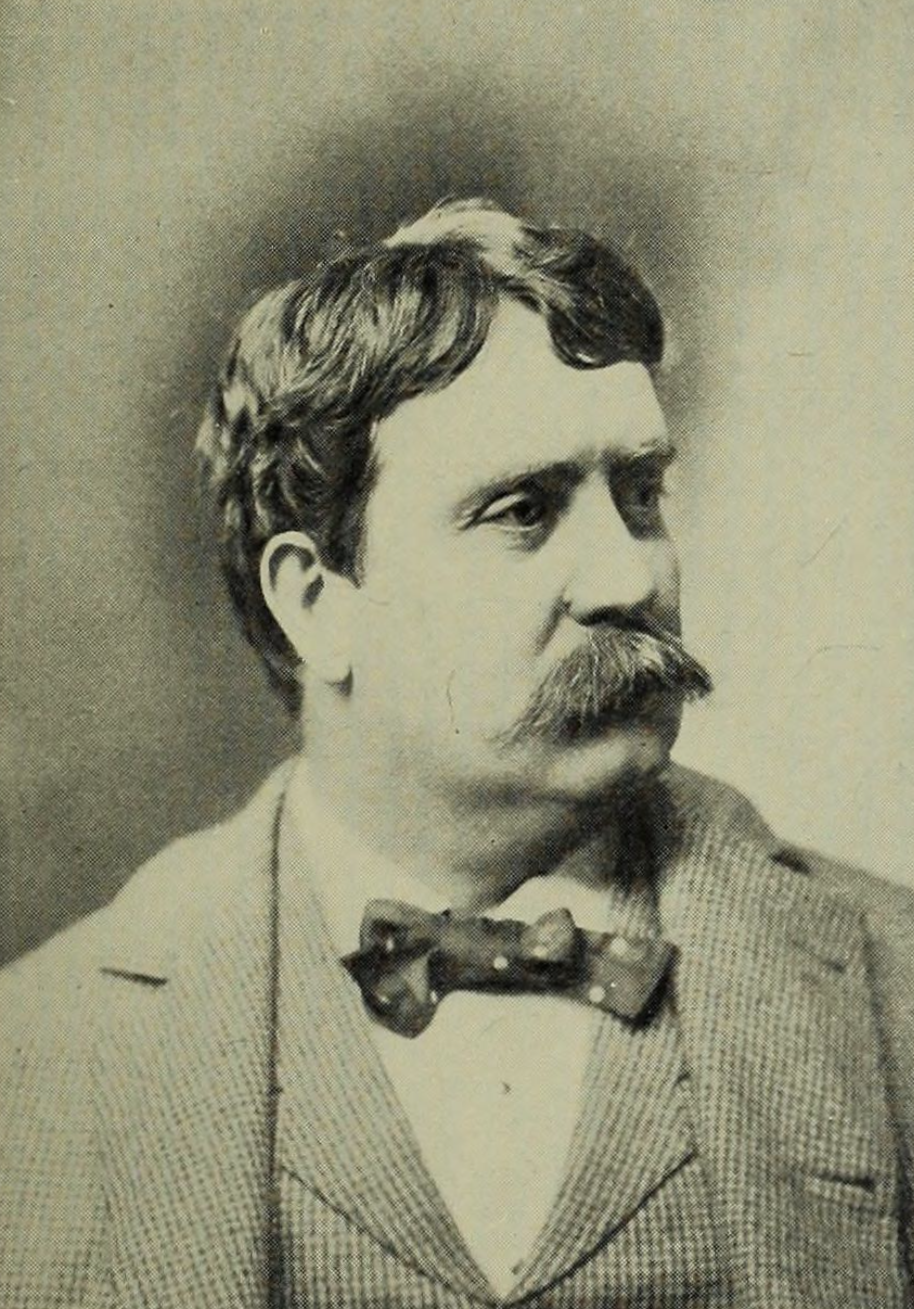

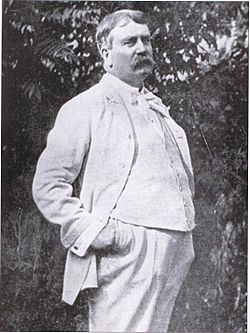

Daniel Burnham

View on Wikipedia

Daniel Hudson Burnham FAIA (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the Beaux-Arts movement, he may have been "the most successful power broker the American architectural profession has ever produced."[1]

Key Information

A successful Chicago architect, he was selected as Director of Works for the 1892–93 World's Columbian Exposition, colloquially referred to as "The White City". He had prominent roles in the creation of master plans for the development of a number of cities, including the Plan of Chicago, and plans for Manila, Baguio and downtown Washington, D.C. He also designed several famous buildings, including a number of notable skyscrapers in Chicago, the Flatiron Building of triangular shape in New York City,[2] Washington Union Station in Washington D.C., London's Selfridges department store, and San Francisco's Merchants Exchange.

Although best known for his skyscrapers, city planning, and for the White City, almost one third of Burnham's total output – 14.7 million square feet (1.37 million square metres) – consisted of buildings for shopping.[3]

Early life

[edit]

Burnham was born in Henderson, New York, the son of Elizabeth Keith (Weeks) and Edwin Arnold Burnham.[4] He was raised in the teachings of the Swedenborgian, also called "The New Church"[5] which ingrained in him the strong belief that man should strive to be of service to others.[6] At the age of eight, Burnham moved to Chicago[4] and his father established there a wholesale drug business which became a success.[7]

Burnham was not a good student, but he was good at drawing. He moved to the eastern part of the country at the age of 18 to be taught by private tutors in order to pass the admissions examinations for Harvard and Yale, failing both apparently because of a bad case of test anxiety. In 1867, when he was 21 he returned to Chicago and took an apprenticeship as a draftsman under William LeBaron Jenney of the architectural firm Loring & Jenney. Architecture seemed to be the calling he was looking for, and he told his parents that he wanted to become "the greatest architect in the city or country".[7]

Nevertheless, the young Burnham still had a streak of wanderlust in him, and in 1869 he left his apprenticeship to go to Nevada with friends to try mining gold, at which he failed. He then ran for the Nevada state legislature and failed to be elected. Broke, he returned again to Chicago and took a position with the architect L. G. Laurean. When the Great Chicago Fire hit the city in October 1871, it seemed as if there would be endless work for architects, but Burnham chose to strike out again, becoming first a salesman of plate glass windows, then a druggist. He failed at the first and quit the second. He later remarked on "a family tendency to get tired of doing the same thing for very long".[7]

Career

[edit]

At age 26, Burnham moved on to the Chicago offices of Carter, Drake and Wight where he met future business partner John Wellborn Root, who was 21 and four years younger than Burnham. The two became friends and then opened an architectural office together in 1873. Unlike his previous ventures, Burnham stuck to this one.[7] Burnham and Root went on to become a very successful firm. Their first major commission came from John B. Sherman, the superintendent of the massive Union Stock Yards in Chicago, which provided the livelihood – directly or indirectly – for one-fifth of the city's population. Sherman hired the firm to build for him a mansion on Prairie Avenue at Twenty-first Street among the mansions of Chicago's other merchant barons. Root made the initial design. Burnham refined it and supervised the construction. It was on the construction site that he met Sherman's daughter, Margaret, whom Burnham married in 1876 after a short courtship.[8] Sherman commissioned other projects from Burnham and Root, including the Stone Gate, an entry portal to the stockyards which became a Chicago landmark.[9]

In 1881, the firm was commissioned to build the Montauk Building, the tallest building in Chicago at the time. To solve the problem of the city's water-saturated sandy soil and bedrock 125 feet (38 m) below the surface, Root came up with a plan to dig down to a "hardpan" layer of clay on which was laid a 2-foot (0.61 m) thick pad of concrete overlaid with steel rails placed at right-angles to form a lattice "grill", which was then filled with Portland cement. This "floating foundation" was, in effect, artificially-created bedrock on which the building could be constructed. The completed building was so tall compared to existing buildings that it defied easy description, and the name "skyscraper" was coined to describe it. Thomas Talmadge, an architect and architectural critic said of the building, "What Chartres was to the Gothic cathedral, the Montauk Block was to the high commercial building."[10]

Burnham and Root went on to build more of the first American skyscrapers, such as the Masonic Temple Building[11] in Chicago. Measuring 21 stories and 302 feet, the temple held claims as the tallest building of its time, but was torn down in 1939.

The talents of the two partners were complementary. Both men were artists and gifted architects, but Root had a knack for conceiving elegant designs and was able to see almost at once the totality of the necessary structure. Burnham, on the other hand, excelled at bringing in clients and supervising the building of Root's designs. They each appreciated the value of the other to the firm. Burnham also took steps to ensure their employees were happy: he installed a gym in the office, gave fencing lessons and let employees play handball at lunch time. Root, a pianist and organist, gave piano recitals in the office on a rented piano. Paul Starrett, who joined the office in 1888 said "The office was full of a rush of work, but the spirit of the place was delightfully free and easy and human in comparison to other offices I had worked in."[12]

Although the firm was extremely successful, there were several notable setbacks. One of their designs, the Grannis Block in which their office was located, burned down in 1885 necessitating a move to the top floor of The Rookery, another of their designs. Then, in 1888, a Kansas City, Missouri, hotel they had designed collapsed during construction, killing one man and injuring several others. At the coroner's inquest, the building's design came in for criticism. The negative publicity shook and depressed Burnham. Then in a further setback, Burnham and Root also failed to win the commission for design of the giant Auditorium Building, which went instead to their rivals, Adler & Sullivan.[13]

On January 15, 1891, while the firm was deep in meetings for the design of the World's Columbian Exposition, Root died after a three-day course of pneumonia. As Root had been only 41 years old, his death stunned both Burnham and Chicago society.[14] After Root's death, the firm of Burnham and Root, which had had tremendous success producing modern buildings as part of the Chicago School of architecture, was renamed D.H. Burnham & Company. After that the firm continued its successes and Burnham extended his reach into city design.[15]

World's Columbian Exposition

[edit]Burnham and Root had accepted responsibility to oversee the design and construction of the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago's then-desolate Jackson Park on the south lakefront. The largest world's fair to that date (1893), it celebrated the 400-year anniversary of Christopher Columbus's famous voyage. After Root's sudden and unexpected death, a team of distinguished American architects and landscape architects, including Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles McKim, Richard M. Hunt, George B. Post, and Henry Van Brunt radically changed Root's modern and colorful style to a Classical Revival style. Only the pavilion by Louis Sullivan was designed in a non-Classical style. To ensure the project's success, Burnham moved his personal residence into a wooden headquarters, called "the shanty" on the burgeoning fairgrounds to improve his ability to oversee construction.[16] The construction of the fair faced huge financial and logistical hurdles, including a worldwide financial panic and an extremely tight timeframe, to open on time.

Considered the first example of a comprehensive planning document in the nation, the fairground featured grand boulevards, classical building facades, and lush gardens. Often called the "White City," it popularized neoclassical architecture in a monumental, yet rational Beaux-Arts style. As a result of the fair's popularity, architects across the U.S. were said to be inundated with requests by clients to incorporate similar elements into their designs.

The control of the fair's design and construction was a matter of dispute between various entities, particularly the National Commission which was headed by George R. Davis, who served as Director-General of the fair. It was also headed by the Exposition Company which consisted of the city's leading merchants, led by Lyman Gage which had raised the money needed to build the fair, and Burnham as Director of Works. In addition the large number of committees made it difficult for construction to move forward at the pace needed to meet the opening day deadline.[17] After a major accident which destroyed one of the fair's premiere buildings, Burnham moved to take tighter control of construction, distributing a memo to all the fair's department heads which read "I have assumed personal control of the active work within the grounds of the World's Columbian Exposition ... Henceforward, and until further notice, you will report to and receive orders from me exclusively."[18]

After the fair opened, Olmsted, who designed the fairgrounds, said of Burnham that "too high an estimate cannot be placed on the industry, skill and tact with which this result was secured by the master of us all."[19] Burnham himself rejected the suggestion that Root had been largely responsible for the fair's design, writing afterwards:

What was done up to the time of his death was the faintest suggestion of a plan ... The impression concerning his part has been gradually built up by a few people, close friends of his and mostly women, who naturally after the Fair proved beautiful desired to more broadly identify his memory with it.[20]

Post-fair architecture

[edit]Nevertheless, Burnham's reputation was considerably enhanced by the success and beauty of the fair. Harvard and Yale both presented him honorary master's degrees ameliorating his having failed their entrance exams in his youth. The common perception while Root was alive was that he was the architectural artist and Burnham had run the business side of the firm; Root's death, while devastating to Burnham personally, allowed him to develop as an architect in a way he might not have, had Root lived on.[21]

In 1901, Burnham designed the Flatiron Building in New York City, a trailblazing structure that utilized an internal steel skeleton to provide structural integrity; the exterior masonry walls were not load-bearing. This allowed the building to rise to 22 stories.[22] The design was that of a vertical Renaissance palazzo with Beaux-Arts styling, divided like a classical column, into base, shaft and capital.[23][24]

Other Burnham post-fair designs included the Land Title Building (1897) in Philadelphia, the first major building in that city not designed by local architects, and known as "the finest example of early skyscraper design" there,[25] John Wanamaker's Department Store (1902–1911) in Philadelphia, now Macy's, which is built around a central court,[26] Wanamaker's Annex (1904, addition: 1907–1910), in New York City, a 19-story full-block building which contains as much floorspace as the Empire State Building,[27] the neo-classical Gimbels Department Store (1908–1912) also in New York, now the Manhattan Mall, with a completely new facade,[28] the stunningly Art Deco Mount Wilson Observatory in the hills above Pasadena, California,[20] and Filene's Department Store (1912) in Boston, the last major building designed by Burnham.[29]

The Philippines

[edit]In 1904, Burnham accepted a commission from Philippines Governor-General William Howard Taft. He had the opportunity to redesign Manila and plan a summer capital to be constructed in Baguio. Due to the Philippines status as a territory, Burnham was able to pursue his vision without having to win local approval. Altogether the project took six months to design, with only six weeks spent in the Philippines. After his plans were approved by William Cameron Forbes, Commissioner of Commerce and Police in the Philippines, Burnham was allowed to choose the principal architect, William E. Parsons. Burnham then departed to keep tabs on the project from the mainland. Burnham's plans emphasized improved sanitation, a cohesive aesthetic (Mission Revival), and visual reminders of government authority. In Manila, wide boulevards radiated out from the capital building. In Baguio, government structures loomed from the cliffs above the town. Burnham Park located in center downtown Baguio was built. The land for the Baguio project, 14,000 acres (5,700 ha) in total, was seized from local Igorots with approval of the Philippine Supreme Court. In Manila, neighborhoods ravaged by the war for independence were left untouched while a luxury hotel, casino, and boat clubs were designed for visiting mainland dignitaries.[30]

City planning and the Plan of Chicago

[edit]Initiated in 1906 and published in 1909, Burnham and his co-author Edward H. Bennett prepared a Plan of Chicago which laid out plans for the future of the city. It was the first comprehensive plan for the controlled growth of an American city and an outgrowth of the City Beautiful movement. The plan included ambitious proposals for the lakefront and river. It also asserted that every citizen should be within walking distance of a park. Sponsored by the Commercial Club of Chicago,[31] Burnham donated his services in hopes of furthering his own cause.

Building off plans and conceptual designs from the World's Fair for the south lakefront,[32] Burnham envisioned Chicago as a "Paris on the Prairie". French-inspired public works constructions, fountains and boulevards radiating from a central, domed municipal palace became Chicago's new backdrop. Though only parts of the plan were actually implemented, it set the standard for urban design, anticipating the future need to control urban growth and continuing to influence the development of Chicago long after Burnham's death.

Plans in additional cities

[edit]

Burnham's city planning projects did not stop at Chicago. Burnham had previously contributed to plans for cities such as Cleveland (the 1903 Group Plan),[33] San Francisco (1905),[34] Manila (1905),[35] and Baguio in the Philippines, details of which appear in the 1909 Plan of Chicago publication. His plans for the redesign of San Francisco were delivered to the Board of Supervisors in September 1905,[36] but in the haste to rebuild the city after the 1906 earthquake and fires Burnham's plans were ultimately ignored. In the Philippines, Burnham's plan for Manila never materialized due to the outbreak of World War II and the relocation of the capital to another city after the war. Some components of the plan, however, did come into fruition including the shore road which became Dewey Boulevard (now known as Roxas Boulevard) and the various neoclassical government buildings around Luneta Park, which very much resemble a miniature version of Washington, D.C., in their arrangement.

In Washington, D.C., Burnham did much to shape the 1901 McMillan Plan which led to the completion of the overall design of the National Mall. The Senate Park Commission, or McMillan Commission established by Michigan Senator James McMillan, brought together Burnham and three of his colleagues from the World's Columbian Exposition: architect Charles Follen McKim, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., and sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Going well beyond Pierre L'Enfant's original vision for the city, the plan provided for the extension of the Mall beyond the Washington Monument to a new Lincoln Memorial and a "pantheon" that eventually materialized as the Jefferson Memorial. This plan involved significant reclamation of land from swamp and the Potomac River and the relocation of an existing railroad station, which was replaced by Burnham's design for Washington Union Station.[37] As a result of his service on the McMillan Commission, in 1910 Burnham was appointed a member and first chairman of the United States Commission of Fine Arts helping to ensure implementation of the McMillan Plan's vision. Burnham served on the commission until his death in 1912.[38]

Influence

[edit]In his career after the fair, Burnham became one of the country's most prominent advocates for the Beaux-Arts movement as well as the revival of Neo-classical architecture which began with the fair.[25] Much of Burnham's work was based on the classical style of Greece and Rome. In his 1924 autobiography, Louis Sullivan, one of the leading architects of the Chicago School, but one who had a difficult relationship with Burnham over an extended period of time, criticized Burnham for what Sullivan viewed as his lack of original expression and dependence on classicism.[39] Sullivan went on to claim that "the damage wrought by the World's Fair will last for half a century from its date, if not longer"[40] – a sentiment edged with bitterness, as corporate America of the early 20th century had demonstrated a strong preference for Burnham's architectural style over Sullivan's.

Burnham is famously quoted as saying, "Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men's blood and probably will not themselves be realized." This slogan has been taken to capture the essence of Burnham's spirit.[41][42]

A man of influence, Burnham was considered the pre-eminent architect in America at the start of the 20th century. He held many positions during his lifetime, including the presidency of the American Institute of Architects.[43] Other notable architects began their careers under his aegis, such as Joseph W. McCarthy. Several of his descendants have worked as influential architects and planners in the United States, including his son, Daniel Burnham Jr., and grandchildren Burnham Kelly and Margaret Burnham Geddes.

Personal life

[edit]Burnham married Margaret Sherman, the daughter of his first major client, John B. Sherman, on January 20, 1876. They first met on the construction site of her father's house. Her father had a house built for the couple to live in. During their courtship, there was a scandal in which Burnham's older brother was accused of having forged checks. Burnham immediately went to John Sherman and offered to break the engagement as a matter of honor but Sherman rejected the offer, saying "There is a black sheep in every family." However, Sherman remained wary of his son-in-law, who he thought drank too much.[44]

Burnham and Margaret remained married for the rest of his life. They had five children—two daughters and three sons—including Daniel Burnham Jr., born in February 1886,[45] who became an architect and urban planner like his father. He worked in his father's firm until 1917, and served as the Director of Public Works for the 1933-34 Chicago World's Fair, known as the "Century of Progress".

The Burnham family lived in Chicago until 1886, when he purchased a 16-room farmhouse and estate on Lake Michigan in the suburb of Evanston, Illinois.[46][47][48][49] Burnham had become wary of Chicago which he felt was becoming dirtier and more dangerous as its population increased. Burnham explained to his mother, whom he did not tell of the move in advance, "I did it, because I can no longer bear to have my children on the streets of Chicago..."[45] When Burnham moved into "the shanty" in Jackson Park to better supervise construction of the fair, his wife, Margaret and their children remained in Evanston.[46]

Beliefs

[edit]Burnham was an early environmentalist, writing: "Up to our time, strict economy in the use of natural resources has not been practiced, but it must be henceforth unless we are immoral enough to impair conditions in which our children are to live," although he also believed the automobile would be a positive environmental factor, with the end of horse-based transportation bringing "a real step in civilization ... With no smoke, no gases, no litter of horses, your air and streets will be clean and pure. This means, does it not, that the health and spirits of men will be better?" Like many men of his time, he also showed an interest in the supernatural, saying "If I were able to take the time, I believe that I could prove the continuation of life beyond the grave, reasoning from the necessity, philosophically speaking, of a belief in an absolute and universal power."[50]

Death

[edit]

When Burnham was in his fifties, his health began to decline. He developed colitis and in 1909 was diagnosed with diabetes, which affected his circulatory system and led to an infection in his foot which was to continue for the remainder of his life.[51]

On April 14, 1912, Burnham and his wife were aboard the RMS Olympic of the White Star Line, traveling to Europe to tour Heidelberg, Germany. When he attempted to send a telegram to his friend Frank Millet who was traveling the opposite direction, from Europe to the United States, on the RMS Titanic, he learned that the ship had sunk in an accident and Millet did not survive. Burnham died only 47 days later[52] from colitis complicated by his diabetes and food poisoning from a meal eaten in Heidelberg.[53][54]

At the time of his death, D.H. Burnham and Co. was the world's largest architectural firm. Even legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright, although strongly critical of Burnham's Beaux Arts European influences, still admired him as a man and eulogized him, saying: "[Burnham] made masterful use of the methods and men of his time ...[As] an enthusiastic promoter of great construction enterprises ...his powerful personality was supreme." The successor firm to Burnham's practice was Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, which continued in some form until 2006.[55] Burnham was interred at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.[56]

Memorials

[edit]Tributes to Burnham include Burnham Park and Daniel Burnham Court in Chicago, Burnham Park in Baguio in the Philippines, Daniel Burnham Court in San Francisco (formerly Hemlock Street between Van Ness Avenue and Franklin Street), the annual Daniel Burnham Award for a Comprehensive Plan (run by the American Planning Association),[57] and the Burnham Memorial Competition which was held in 2009 to create a memorial to Burnham and his Plan of Chicago.[58] Collections of Burnham's personal and professional papers, photographs, and other archival materials are held by the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago.

In addition, the Reliance Building in Chicago which was designed by Burnham and Root, is now the Hotel Burnham, although Root was the primary architect before his death in 1891.

Notable commissions

[edit]-

Flatiron Building (1901)

-

Reliance Building (1890–1895)

-

Union Stock Yard Gate, Chicago (1879)

-

The Rookery Building in Chicago, (1886)

-

770 Broadway, New York City (1904, addition: 1907–1910)

-

Pennsylvania Union Station (1900–1902)

-

Washington Union Station in Washington, D.C., (1908)

-

Union Station, El Paso, Texas (1905–1906)

Chicago

[edit]- Union Stock Yard Gate (1879)

- Union Station (1881)

- Montauk Building (1882–1883)

- Kent House (1883)

- Rookery Building (1886)

- Reliance Building (1890–1895)

- Monadnock Building (northern half, 1891)

- Marshall Field and Company Building (now Macy's, 1891–1892)

- Fisher Building (1896)

- Orchestra Hall (1904)

- Heyworth Building (1904)

- Sullivan Center (Carson, Pirie, Scott & Co. addition, 1906)[59]

- Boyce Building, on the National Register of Historic Places (1915)[60][61]

- Butler Brothers Warehouse (now The Gogo Building) (1913)

Cincinnati

[edit]- Union Savings Bank and Trust Building (later the Fifth Third Union Trust Building, the Bartlett Building and now the Renaissance Hotel, 1901)[62]

- Tri-State Building (1902)[62]

- First National Bank Building (later the Clopay Building and now the Fourth & Walnut Center, 1904)

- Fourth National Bank Building (1904)[62]

- Cincinnati Art Museum, Schmidlapp Extension (opened 1907)

Detroit

[edit]- Majestic Building (1896, demolished 1962)

- Ford Building (1907–1908)

- Dime Building (1912)

Indianapolis

[edit]- Indianapolis Traction Terminal, (1903, demolished 1972)

- Barnes and Thornburg Building, (formerly the Merchants National Bank Building), (1912)

New York

[edit]- Flatiron Building (1901)[63][A]

- Wanamaker's Annex, full-city-block department store (1904, addition: 1907–1910)

- Gimbels Department Store (1908–1912)

Philadelphia

[edit]- Land Title Building (1897)

- John Wanamaker's Department Store (now housing a Macy's and offices, 1902–1911)

Pittsburgh

[edit]- Union Trust Building (1898, 337 Fourth Avenue – not the 1917 structure of the same name on Grant Street)

- Pennsylvania Union Station (1900–1902)

- Frick Building (1902)

- McCreery Department Store (now offices – 300 Sixth Avenue Building, 1904)

- Highland Building (1910, 121 South Highland Avenue)

- Henry W. Oliver Building (1910)

San Francisco

[edit]- Merchants Exchange Building (1904)

- The Mills Building (1892, restoration and expansion: 1907–1909)

Washington, D.C.

[edit]- Washington Union Station (1908)

- Postal Square Building (1911–1914)

- Columbus Fountain (1912)

Others

[edit]- Keokuk Union Depot, Keokuk, Iowa (1891)[65]

- Pearsons Hall of Science, Beloit, Wisconsin (1892–1893)

- Ellicott Square Building, Buffalo, New York (1896)

- Columbus Union Station, Columbus, Ohio (1897)

- Wyandotte Building, Columbus, Ohio (1897–1898)

- Gilbert M. Simmons Memorial Library, Kenosha, Wisconsin (1900)

- Continental Trust Company Building, Baltimore (1901, southeast corner South Calvert and East Baltimore Streets, damaged during Great Baltimore Fire of February 1904, but upon inspection the steel and masonry exterior was deemed sound; the damaged interior was later reconstructed)

- First National Bank Building (now Fayette Building), Uniontown, Pennsylvania (1902)

- Pennsylvania Railroad Station, Richmond, Indiana (1902)

- Cleveland Mall with Arnold Brunner and John Carrère, Cleveland (1903)

- Union Station, El Paso, Texas (1905–1906)

- The Fleming Building, Des Moines, Iowa (1907)

- Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad station, Vicksburg, Mississippi (1907)[65]

- Duluth Civic Center Historic District, Duluth, Minnesota, (1908–1909, four buildings)

- Selfridge & Co. Department Store, Oxford Street, London (1909)

- Miners National Bank Building, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania (1911, now Citizens Bank Financial Center)

- Terminal Arcade, Terre Haute, Indiana (1911)

- Filene's Department Store, Boston (1912)

- Starks Building, Louisville, Kentucky (1912)

- Second National Bank Building, Toledo, Ohio (1913, now Riverfront Apartments)

- El Granada, California (city master plan)

- First National Bank Building, Milwaukee

- Joliet Public Library, Joliet, Illinois (1903)

- Kenilworth Train Station, Kenilworth, Illinois

- Mount Wilson Observatory, Pasadena, California

- First Presbyterian Church, Evanston, Illinois (1895)

- U.S._Bank_Building_(Spokane), Spokane,_Washington (1910)

Philippines

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]- Make No Little Plans - Daniel Burnham and the American City[66] is the first feature-length documentary film about noted architect and urban planner Daniel Hudson Burnham, produced by the Archimedia Workshop. National distribution in 2009 coincided with the centennial celebration of Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett's 1909 Plan of Chicago.

- The Devil in the White City, a non-fiction book by Erik Larson, intertwines the true tales of two men: H.H. Holmes, a serial killer famed for his 'murderous hotel' in Chicago, and Daniel Burnham.

- In the role-playing game Unknown Armies, James K. McGowan, the True King of Chicago, quotes Daniel Burnham and regards him as a paragon of the Windy City's mysterious and magical past.

- In the episode "Legendaddy" of TV sitcom How I Met Your Mother, the character Ted, who is professor of architecture, describes Burnham as an "architectural chameleon".

- In the episode "Household" of Hulu original The Handmaid's Tale, Daniel Burnham is indirectly mentioned and only named as a Heretic for the reason the Gilead government demolished and replaced Washington Union Station in Washington, D.C..

- In Joffrey Ballet's version of The Nutcracker, choreographed by Christopher Wheeldon, Daniel Burnham, is the Drosselmeyer character of the ballet.[67]

References

[edit]Informational notes

- ^ "By 1903, Chicago's Daniel H. Burnham had completed the twenty-one-story Fuller Building in New York City, which the public quickly redubbed the Flatiron Building because of its iconic triangular plan."[64]

Citations

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (March 2, 2009). "Toddlin' Town". The New Yorker (published March 9, 2009). Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ Laurin, Dale (2008). "Grace and Seriousness in the Flatiron Building and Ourselves" (PDF). Aesthetic Realism Looks at NYC. Aesthetic Realism Foundation. pp. 1–4. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Graham, Wade (2016) Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas That Shape the World New York: Harper Perennial. p.207 ISBN 978-0-06-219632-3

- ^ a b Norton-Burhnam House, National Register of Historic Places Registration, National Park Service, January 8, 2016

- ^ "Website". New Church. June 20, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ Carl Smith, The Plan of Chicago: Daniel Burnham and the Remaking of the American City, p. 56

- ^ a b c d Larson (2003), p.19

- ^ Larson (2003), pp.20-21

- ^ Larson (2003), p.22

- ^ Larson (2003) pp.24-25

- ^ "Masonic Temple, Chicago". Old Chicago in Vintage Postcards. Archived from the original on May 18, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ Larson (2003) pp.26-27

- ^ Larson (2003) pp.29-30

- ^ Larson (2003), pp.104-108

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 58.

- ^ Larson (2003), pp.76-77

- ^ Larson (2003), pp.119-120

- ^ Larson (2003), p.178

- ^ Larson (2003), p.283

- ^ a b Larson (2003), p.377

- ^ Larson (2003), pp.376–377

- ^ Terranova, Antonino (2003) Skyscrapers White Star Publishers. ISBN 88-8095-230-7

- ^ "Flatiron Building" Archived February 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine on Destination 360

- ^ Gillon, Edmund Vincent (photographs) and Reed, Henry Hope (text). Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide New York: Dover, 1988. p. 26

- ^ a b Gallery, John Andrew, ed. (2004), Philadelphia Architecture: A Guide to the City (2nd ed.), Philadelphia: Foundation for Architecture, p. 83, ISBN 0962290815

- ^ Gallery, John Andrew, ed. (2004), Philadelphia Architecture: A Guide to the City (2nd ed.), Philadelphia: Foundation for Architecture, p. 85, ISBN 0962290815

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ Southworth, Susan; Southworth, Michael (1992). AIA Guide to Boston (2 ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot. p. 19. ISBN 0-87106-188-0.

- ^ Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2019), p. 123-136.

- ^ "The Commercial Club of Chicago: Purpose & History". Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "Chicago's lake front". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ Burnham, Daniel H.; Carrere, John M.; Brunner, Arnold W. (August 1903). The Group Plan of the Public Buildings of the City of Cleveland (PDF) (Report). City of Cleveland. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Burnham, Daniel H.; Bennett, Edward H. (September 1905). O'Day, Edward F. (ed.). Report on a plan for San Francisco (Report). Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Burnham, D.H.; Anderson, Pierce (June 28, 1905). Exhibit B: Report on Improvement of Manila (Report). Government Printing Office. pp. 627–635. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Adams, C.F. (August 12, 1911). "Burnham's Plan for the Adornment of the Exposition City". San Francisco Call. Vol. 110, no. 73. p. 19. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Movie: "Make No Little Plans"

- ^ Thomas E. Luebke, ed., Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2013): Appendix B, p. 541.

- ^ Sullivan, Louis (1924) The Autobiography of an Idea, New York: Press of the American Institute of Architects. pp.320-21

- ^ Sullivan, Louis (1924) The Autobiography of an Idea, New York: Press of the American Institute of Architects. p.325

- ^ Abbot, Willis J. (January 18, 1927) "How Chicago Is Making Its Vision of Civic Splendor a Reality Is Told by Man Who Led in Project That Proves Economic Value of 'Mere Beauty'; Story of Commercial City's Education in Aesthetics Recited by Charles H. Wacker; Chicago Plan Commission's Former Head Shows How Transformation Has Been Wrought - Ideal Improvements, Once Pictured, Became Visible Goals of Community Endeavor - Were Even Taught In Schools" The Christian Science Monitor. p.8

- ^ Moore, Charles (1921) Daniel H. Burnham, Architect, Planner of Cities. Boston, Houghton Mifflin. Volume 2: Chapter XXV: "Closing in 1911-1912"

- ^ "AIA Presidents". American Institute of Architects. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ Larson (2003) p.21

- ^ a b Larson (2003), p.28

- ^ a b Larson (2003), p.128

- ^ Rodkin, Dennis (November 8, 2010) "Evanston House Occupies Former Daniel Burnham Estate" Chicago Real Estate

- ^ Bullington, Jonathan (April 30, 2009) "Home in Evanston Fills My Longing Daniel Burnhams Evanston" Archived May 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune

- ^ Rodkin, Dennis, (May 10, 2016) "Historical Evanston mansion coming on market at $5.3 million" Crain's Chicago Business

- ^ Larson (2003), p.378

- ^ Larson (2003), pp.378

- ^ Larson (2003), pp.3-7,389-90

- ^ Staff (June 2, 1912) "Daniel Burnham, Architect, Dead" Chicago Tribune

- ^ Hines, Thomas S. (June 15, 1979). Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner. University of Chicago Press. pp. 360. ISBN 978-0-226-34171-2.

daniel burnham cause of death food poisoning.

- ^ "Burham in Evanston Talk" The Burnham Plan Centennial

- ^ Lancelot, Barbara (1988) A Walk Through Graceland Cemeter Chicago: Chicago Architecture Foundation. pp. 34-35

- ^ "National Planning Awards". American Planning Association. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "Design Competition and Exhibit". Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ "Schlesinger & Mayer Building". chicagology.com. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "Illinois - Cook County". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ^ Randall, Frank Alfred; John D. Randall (1999). History of the Development of Building Construction in Chicago. Urbana and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 286. ISBN 0-252-02416-8. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Architectural Treasures of the Queen City: Part II". December 3, 2012.

- ^ Alexiou 2010, p. 59.

- ^ Brown, Dixon & Gillham 2014.

- ^ a b Potter, Janet Greenstein (1996). Great American Railroad Stations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 264, 320–321. ISBN 978-0-471-14389-5.

- ^ "Daniel Burnham Film". The Archimedia Workshop. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ "Don't Miss This Behind-the-Scenes PBS Documentary of Christopher Wheeldon's "Nutcracker" at Joffrey Ballet". Pointe Magazine. November 29, 2017.

Bibliography

- Alexiou, Alice Sparberg (2010). The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City that Arose With It. New York: Thomas Dunne/St. Martin's Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-312-38468-5.

- Brown, Lance Jay; Dixon, David & Gillham, Oliver (June 21, 2014). Urban Design for an Urban Century: Shaping More Livable, Equitable, and Resilient Cities (2nd ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-45363-6.

- Burnham, Daniel H. and Bennett, Edward H. (1910) Plan of Chicago, Chicago: The Commercial Club

- "Daniel Burnham". Chicago Landmarks. Archived from the original on October 10, 2004. Retrieved September 21, 2004.

- Jameson, D. "Daniel Hudson Burnham". Artists Represented. Archived from the original on December 16, 2005. Retrieved December 14, 2005.

- Larson, Erik (2003). The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. New York, New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-609-60844-4.

- Moore, Charles (1921). "XXV "Closing in 1911–1912"". Daniel H. Burnham, Architect, Planner of Cities, Volume 2. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. p. 1921.

- Stolze, Greg (February 2002). Unknown Armies. St Paul, Minneapolis: Atlas Games. ISBN 1-58978-013-2.

- "Daniel Hudson Burnham". Chicago Stories. Archived from the original on August 21, 2004. Retrieved September 24, 2004.

- "Today In History: September 4". American Memory. The Library of Congress. Retrieved September 24, 2004.

External links

[edit]Daniel Burnham

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Family Background and Childhood

Daniel Hudson Burnham was born on September 4, 1846, in the rural village of Henderson, Jefferson County, New York, to Edwin Act Burnham, a businessman of modest means, and his wife Elizabeth Keith Weeks Burnham.[8][9] He was the sixth of seven children and the youngest son in the family.[10] The Burnhams followed the Swedenborgian faith, a denomination emphasizing rational theology, moral discipline, and intellectual pursuit, which shaped the family's approach to child-rearing and education.[11][12] In January 1855, at the age of eight, Burnham moved with his family to Chicago, Illinois, drawn by the city's booming economic prospects amid its transformation into a major Midwestern hub.[9][13] There, his father established a wholesale drug business that achieved commercial success, providing the family with middle-class stability.[14][11] Burnham's childhood in Chicago involved attendance at local public schools, where he proved an indifferent and restless pupil, showing little academic inclination despite the Swedenborgian emphasis on self-improvement.[15][7] His early years reflected a blend of rural origins and urban adaptation, fostering resilience amid Chicago's dynamic, opportunity-laden environment.[13]Architectural Training and Early Influences

Burnham received no formal architectural education, having failed entrance examinations for institutions such as Harvard, Yale, and the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in the mid-1860s, after which he briefly pursued silver mining in Nevada and other ventures before returning to Chicago around 1867.[13] Instead, his training consisted of practical apprenticeships in local firms amid Chicago's rapid post-Great Fire reconstruction, which emphasized functional, fire-resistant commercial structures.[16] In 1867, at age 21, Burnham secured a position as a draftsman apprentice under William LeBaron Jenney at the firm of Loring & Jenney, where he gained foundational exposure to innovative structural techniques, including early experiments with iron skeleton framing that would underpin the skyscraper era—Jenney being credited as the "father of the skyscraper" for such advancements.[17] [15] He supplemented this with brief stints at other offices, such as those of John Van Osdel, Chicago's pioneering architect, honing skills in drafting and site adaptation to the city's flat terrain and economic demands.[15] By 1872, Burnham joined Carter, Drake & Wight as a draftsman, encountering John Wellborn Root, a fellow apprentice whose artistic sensibility complemented Burnham's pragmatic, business-oriented approach to architecture; this meeting laid the groundwork for their influential 1873 partnership.[16] [13] Early influences thus centered on Jenney's engineering rationalism and the Chicago School's emphasis on height, light, and efficiency driven by real estate pressures, rather than academic classicism, fostering Burnham's view of architecture as a scalable enterprise responsive to urban growth.[13]Professional Beginnings

Partnership with John Wellborn Root

Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root formed the architectural firm Burnham & Root in 1873, having met as draftsmen at the Chicago office of Carter, Drake, and Wight.[16][18] Burnham, born in 1846, handled business development, client acquisition, and project management, leveraging his organizational skills and connections.[19] Root, born in 1850 and trained at New York University and in England, served as the primary designer and engineer, bringing inventive structural solutions and aesthetic versatility.[20][21] Their complementary strengths enabled the firm to thrive in Chicago's post-Great Fire reconstruction boom, producing over 300 buildings in 18 years.[22] The partnership pioneered advancements in tall building construction amid Chicago's challenging subsoil, developing "floating" raft foundations and hybrid iron-and-steel skeletal frames to support greater heights.[16] Early commissions included luxury residences, such as the 1874 mansion for John B. Sherman on Prairie Avenue, establishing their reputation among the city's elite.[18] Commercial projects followed, with the Montauk Block (1882–1883) marking an early milestone as a 10-story office building featuring extensive terra cotta cladding for fire resistance.[18] The firm progressed to innovative skyscrapers like the 10-story Rand McNally Building (1889), utilizing an all-steel frame and standing 148 feet tall.[19] Iconic works included the Rookery Building (1886), praised for its light court with skylit iron-and-glass ornamentation that flooded interior spaces with natural light; the Monadnock Building's northern half (1891), demonstrating load-bearing masonry at unprecedented scale; and the Chicago Masonic Temple (1890–1892), which reached 22 stories and briefly held the title of world's tallest building upon completion.[18][16] These structures evolved from Romanesque influences toward more functional, vertically expressive forms, influencing the Chicago School's emphasis on height and efficiency.[16] Root's sudden death from pneumonia on January 15, 1891, at age 41—contracted after a business trip to Atlanta—abruptly ended the partnership, leaving Burnham profoundly affected and several projects unfinished.[20][23] Burnham reorganized the firm as D. H. Burnham & Co., completing Root's designs like the Masonic Temple and Reliance Building (1890–1895), which advanced curtain-wall construction with terra cotta and large glass areas.[18] The collaboration's legacy lay in transforming Chicago's skyline, proving that innovative engineering could enable safe, economical high-rises on unstable ground.[16]Pre-Exposition Projects and Skyscraper Innovations

In 1873, Daniel Burnham partnered with John Wellborn Root to establish the firm Burnham & Root in Chicago, initially focusing on residential and small commercial commissions amid the city's post-fire rebuilding boom.[3] The partnership quickly expanded to larger projects, leveraging Root's engineering expertise and Burnham's business acumen to secure high-profile clients, including the Chicago Board of Trade and real estate developers.[16] Early works included the 1879 Union Stock Yard Gate, a monumental limestone archway symbolizing Chicago's meatpacking industry, constructed with robust masonry to withstand heavy traffic.[4] By the early 1880s, Burnham & Root pioneered multi-story office buildings, with the Montauk Block (1882–1883) marking a key advancement as Chicago's first all-masonry skyscraper at 10 stories and 130 feet tall, featuring innovative grillage foundations—layered steel beams in concrete—to distribute weight over Chicago's unstable clay soil.[24] The Rookery Building (1885–1886), a 12-story structure at 209 South LaSalle Street, integrated a steel frame with a light court of glass and iron ornamentation, allowing natural light to penetrate deeper into interior spaces while employing fire-resistant terracotta cladding.[25] This design balanced structural efficiency with aesthetic appeal, using ornamental ironwork that Root detailed personally.[26] The firm advanced skyscraper technology through full steel-skeleton construction, exemplified by the Rand McNally Building (1889) on Adams Street, their first fully steel-framed structure at 10 stories and 148 feet, which incorporated cantilever footings for enhanced stability on soft ground.[19] [27] The Masonic Temple Building (1890–1892), rising 22 stories to 302 feet, became the world's tallest building upon completion, utilizing a riveted steel skeleton clad in brick and terracotta for fireproofing, though its massive piers strained foundation limits.[28] Root initiated the Reliance Building (1890–1895) before his 1891 death, introducing a pioneering terracotta curtain wall system with large plate-glass windows that maximized daylight and ventilation, reducing reliance on interior load-bearing walls.[16] These projects innovated skyscraper design by prioritizing skeletal steel framing over masonry load-bearing walls, enabling greater heights and open floor plans; Root's contributions included refined riveting techniques and the integration of electric lighting and elevators, as seen in the Rookery's early adoption of such systems.[29] Fireproofing via hollow terracotta tiles and concrete encasements addressed Chicago's frequent blazes, while expansive window areas—up to 50% of facades in the Reliance—responded to demands for natural light in dense urban settings.[24] Burnham & Root's iterative approach, informed by site-specific engineering tests, established precedents for modern high-rises, influencing subsequent architects despite Root's untimely death halting further direct collaboration.[16]World's Columbian Exposition

Appointment and Leadership Role

In 1890, the firm of Burnham & Root, a leading Chicago architectural practice known for innovative skyscraper designs, was commissioned by the World's Columbian Exposition's organizers to coordinate planning for the event's structures in Jackson Park.[2] Following the sudden death of partner John Wellborn Root on January 15, 1891, Burnham reorganized the firm under his own name and took sole charge of the firm's responsibilities for the exposition.[30] He was subsequently appointed Director of Works by the exposition's directing board, a role that positioned him to oversee the entire construction effort amid tight deadlines and logistical challenges.[31] Burnham's leadership involved assembling and directing a consultancy of ten prominent American architects, including Richard Morris Hunt as chief of the board of architects, to ensure unified design standards across the fairgrounds.[32] He played a key role in selecting firms for major buildings, such as advocating for non-resident architects to bring prestige and expertise to the Court of Honor structures.[32] Under his direction, the exposition's works were divided into specialized departments covering construction, grounds, and utilities, enabling efficient management of the transformative development of the previously undeveloped site.[33] Burnham enforced a cohesive classical aesthetic inspired by Beaux-Arts principles, rejecting initial proposals for disparate styles in favor of monumental uniformity that symbolized American progress.[34] His organizational acumen facilitated collaboration among egos of leading designers, averting potential conflicts and delivering the "White City" on schedule for the May 1, 1893, opening despite setbacks like labor strikes and weather delays.[33] This role elevated Burnham's national stature, demonstrating his capacity for large-scale project management rooted in practical engineering and diplomatic coordination.[2]Design Execution and Classical Aesthetic

Daniel Burnham served as chief of construction for the World's Columbian Exposition, overseeing the coordination of designs by a team of leading architects including Richard M. Hunt, Peabody & Stearns, and McKim, Mead & White.[35][36] To achieve aesthetic unity, Burnham enforced Beaux-Arts principles, mandating a uniform cornice height of 60 feet and a 25-foot bay module across facades while rejecting proposals for towers that would disrupt neoclassical harmony.[35] This approach prioritized classical European motifs—such as columns, pediments, and symmetrical layouts—over contemporary American industrial styles, resulting in the fair's designation as the "White City."[36][37] The execution involved constructing temporary buildings using staff, a plaster-like mixture applied over wooden frames and painted white to simulate marble, enabling rapid assembly of grand-scale structures like the Administration Building and Machinery Hall.[35] Burnham's oversight extended to the Court of Honor, where neoclassical facades dominated, featuring highly decorative surfaces, statues, and balanced proportions that evoked ancient ideals on a monumental scale.[37][36] Deviations, such as Louis Sullivan's Transportation Building with its more ornate, non-white design, were limited to peripheral areas to preserve the central aesthetic coherence.[35] This deliberate classical aesthetic, implemented under Burnham's direction, transformed Jackson Park into a vision of ordered splendor, with axial planning, lagoons, and unified white tones that contrasted sharply with Chicago's emerging skyscraper landscape.[35][37] The fair's architectural execution not only met the deadline for the 1893 opening but also demonstrated the feasibility of large-scale collaborative design, influencing subsequent urban projects through its emphasis on symmetry, balance, and visual magnificence.[36]