Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Delphinium

View on Wikipedia

| Delphinium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Delphinium elatum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Ranunculales |

| Family: | Ranunculaceae |

| Subfamily: | Ranunculoideae |

| Tribe: | Delphinieae |

| Genus: | Delphinium L. |

Delphinium is a genus of about 300 species of annual and perennial flowering plants in the family Ranunculaceae, native throughout the Northern Hemisphere and also on the high mountains of tropical Africa. The genus was erected by Carl Linnaeus.[1]

All members of the genus Delphinium are toxic to humans and livestock.[2] The common name larkspur is shared between perennial Delphinium species and annual species of the genus Consolida.[3] Molecular data show that Consolida, as well as another segregate genus, Aconitella, are both embedded in Delphinium.[4]

The genus name Delphinium derives from the Ancient Greek word δελφίνιον (delphínion) which means "dolphin", a name used in De Materia Medica for some kind of larkspur.[5][6][7] Pedanius Dioscorides said the plant got its name because of its dolphin-shaped flowers.[8]

Habitat

[edit]Species with short stems and few flowers such as Delphinium nuttallianum and Delphinium bicolor appear in habitats like prairies and the sagebrush steppe. Tall and robust species with many flowers, such as Delphinium occidentale, appear more often in forests.[9]

Description

[edit]

The leaves are deeply lobed with three to seven toothed, pointed lobes in a palmate shape. The main flowering stem is erect, and varies greatly in size between the species, from 10 centimetres in some alpine species, up to 2 m tall in the larger meadowland species.[citation needed]

In June and July (Northern Hemisphere), the plant is topped with a raceme of many flowers, varying in colour from purple and blue, to red, yellow, or white. The flowers are bilaterally symmetrical and have many stamens.[9] In most species, each flower consists of five petal-like sepals which grow together to form a hollow pocket with a spur at the end, which gives the plant its name, usually more or less dark blue. Within the sepals are four true petals, small, inconspicuous, and commonly coloured similarly to the sepals. The uppermost sepal is spurred, and encloses the nectar-secreting spurs of the two upper petals.[10]

The seeds are small and often shiny black. The plants flower from late spring to late summer, and are pollinated by butterflies and bumble bees. Despite the toxicity, Delphinium species are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species, including the dot moth and small angle shades.[11]

Taxonomy

[edit]Delineation of Delphinium

[edit]

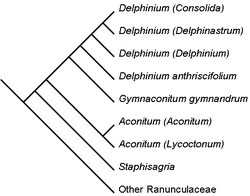

Genetic analysis suggests that Delphinium sensu lato, as it was delineated before the 21st century, is polyphyletic. Nested within Delphinium s.l. are Aconitella, Consolida, and Aconitum. To make Delphinium monophyletic, several interventions were made. The new genus Staphisagria was erected containing Staphisagria macrosperma (D. staphisagria), S. requienii (D. requini) and S. picta (D. pictum), representing the sister group to all other Delphinieae.[12][13] Further genetic analysis has shown that the two large subgenera Aconitum (Aconitum) and Aconitum (Lycoctonum) are the sister group to Aconitum gymnandrum, Delphinium (Delphinium), Delphinium (Delphinastrum), Consolida and Aconitella. To make Aconitum monophyletic, A. gymnandrum has now been reassigned to a new monotypic genus, Gymnaconitum. Finally, Consolida and Aconitella are synonymized with Delphinium.[14][15]

Subgenera

[edit]D. arthriscifolium is sister to all other species of Delphinium sensu stricto (so excluding Staphisagria). It should be placed in its own subgenus, but no proposal naming this subgenus has been made yet.[citation needed] The subgenera Delphinium (Delphinium) and Delphinium (Delphinastrum) are sister to the group consisting of the species of Consolida and Aconitella, which together make up the subgenus Delphinium (Consolida). Aconitella cannot be retained as a subgenus because A. barbata does not cluster with the remaining species previously assigned to that genus, without creating five further subgenera.

Selected species

[edit]Species include:

- Delphinium andersonii

- Delphinium arthriscifolium

- Delphinium bakeri

- Delphinium barbeyi

- Delphinium bicolor

- Delphinium brunonianum

- Delphinium californicum

- Delphinium calthifolium

- Delphinium cardinale

- Delphinium carolinianum

- Delphinium cheilanthum

- Delphinium consolida

- Delphinium decorum

- Delphinium denudatum

- Delphinium depauperatum

- Delphinium elatum

- Delphinium exaltatum

- Delphinium formosum

- Delphinium glaucum

- Delphinium gracilentum

- Delphinium grandiflorum

- Delphinium gypsophilum

- Delphinium hansenii

- Delphinium hesperium

- Delphinium hutchinsoniae

- Delphinium hybridum

- Delphinium inopinum

- Delphinium ithaburense

- Delphinium leucophaeum

- Delphinium luteum

- Delphinium malabaricum

- Delphinium nudicaule

- Delphinium nuttallianum

- Delphinium occidentale

- Delphinium parishii

- Delphinium parryi

- Delphinium patens

- Delphinium pavonaceum

- Delphinium peregrinum

- Delphinium polycladon

- Delphinium purpusii

- Delphinium recurvatum

- Delphinium robustum

- Delphinium scopulorum

- Delphinium stachydeum

- Delphinium tricorne

- Delphinium trolliifolium

- Delphinium uliginosum

- Delphinium umbraculorum

- Delphinium variegatum

- Delphinium viridescens

Reassigned species

[edit]Several species of Delphinium have been reassigned:[15]

- D. pictum = Staphisagria picta

- D. requienii = Staphisagria requienii

- D. staphisagria = Staphisagria macrosperma

Ecology

[edit]Delphiniums can attract butterflies and other pollinators.[16]

Cultivation

[edit]

Various delphiniums are cultivated as ornamental plants, for traditional and native plant gardens. The numerous hybrids and cultivars are primarily used as garden plants, providing height at the back of the summer border, in association with roses, lilies, and geraniums.[citation needed]

Most delphinium hybrids and cultivars are derived from D. elatum. Hybridisation was developed in the 19th century, led by Victor Lemoine in France.[17] Other hybrid crosses have included D. bruninianum, D. cardinale, D. cheilanthum, and D. formosum.[18]

Numerous cultivars have been selected as garden plants, and for cut flowers and floristry. They are available in shades of white, pink, purple, and blue. The blooming plant is also used in displays and specialist competitions at flower and garden shows, such as the Chelsea Flower Show.[19]

The 'Pacific Giant' hybrids are a group with individual single-colour cultivar names, developed by Reinelt in the United States. They typically grow to 1.2–1.8 m (4–6 ft) tall on long stems, by 60–90 cm (2–3 ft) wide. They reportedly can tolerate deer.[16] Millennium delphinium hybrids, bred by Dowdeswell's in New Zealand, are reportedly better in warmer climates than the Pacific hybrids.[20][21] Flower colours in shades of red, orange, and pink have been hybridized from D. cardinale by Americans Reinelt and Samuelson.[18]

Since 2024 the UK National Collection of delphiniums has been held by Colin Parton at Delph Cottage Garden, south east of Leeds. Parton has over 100 cultivars, 21 of which are on the endangered list on Plant Heritage's Threatened Plants Programme. He occasionally opens his garden to the public in return for a donation to the charity Cancer Research.[22][23]

Award of garden merit

[edit]The following delphinium cultivars have received the Award of Garden Merit from the British Royal Horticultural Society:[24]

| Name | Height (m) | Flower colour | Eye colour | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'Atholl' | 1.5 | white | brown | [25] |

| 'Blue Dawn' | 2.2 | mauve (pale) | brown | [26] |

| 'Blue Nile' | 1.5 | blue (mid) | white | [27] |

| 'Bruce' | 2.0 | violet (deep) | buff | [28] |

| 'Can-can' | 1.5 | violet (pale) | (double) | [29] |

| 'Centurion Sky Blue' | 1.5 | blue (light) | white | [30] |

| 'Cherub' | 1.5 | mauve (pale) | cream | [31] |

| 'Clifford Sky' | 2.0 | blue (sky) | white | [32] |

| 'Conspicuous' | 1.5 | mauve | brown | [33] |

| 'Elisabeth Sahin' | 1.5 | white | cream | [34] |

| 'Elizabeth Cook' | 1.5 | white | white | [35] |

| 'Emily Hawkins' | 1.5 | lilac | brown | [36] |

| 'Faust' | 1.8 | blue (deep) | black | [37] |

| 'Fenella' | 1.5 | blue (dark) | black | [38] |

| 'Foxhill Nina' | 1.5 | pink (pale) | white | [39] |

| 'Galileo' | 1.8 | blue (mid) | black | [40] |

| 'Holly Cookland Wilkins' | 2.5 | violet | brown | [41] |

| 'Jill Curley' | 2.1 | white | cream | [42] |

| 'Kennington Classic' | 2.5 | white | yellow | [43] |

| 'Kestrel' | 2.0 | blue (bright) | brown | [44] |

| 'Langdon's Blue Lagoon' | 1.9 | blue (mid) | white | [45] |

| 'Langdon's Pandora' | 2.5 | blue (sky) | brown | [46] |

| 'Lilian Bassett' | 1.5 | white | brown | [47] |

| 'Lord Butler' | 1.5 | blue (light) | white | [48] |

| 'Lucia Sahin' | 2.0 | pink/purple | brown | [49] |

| 'Margaret' | 1.5 | blue (bright) | white | [50] |

| 'Michael Ayres' | 1.5 | violet (deep) | brown | [51] |

| 'Min' | 2.0 | violet | brown | [52] |

| 'Olive Poppleton' | 2.5 | white | yellow | [53] |

| 'Oliver' | 1.5 | blue (light) | black | [54] |

| 'Our Deb' | 1.5 | pink (pale) | brown | [55] |

| 'Purple Velvet' | 1.5 | violet | brown/yellow | [56] |

| 'Raymond Lister' | 1.7 | blue (mid) | brown | [57] |

| 'Rosemary Brock' | 1.5 | pink | brown | [58] |

| 'Rosy Future' | 1.2 | pink | white/black | [59] |

| 'Spindrift' | 1.5 | lilac (pale) | white | [60] |

| 'Sungleam' | 2.0 | cream | yellow | [61] |

| 'Sunkissed' | 1.5 | white | yellow | [62] |

| 'Sweethearts' | 2.5 | pink (rose) | white | [63] |

| 'Tiddles' | 1.5 | mauve | (double) | [64] |

| 'Walton Gemstone' | 2.0 | violet (pale) | white | [65] |

Toxicity

[edit]All parts of these plants are considered toxic to humans, especially the younger parts,[2] causing severe digestive discomfort if ingested, and skin irritation.[2][3][10][66] Larkspur, especially tall larkspur, is a significant cause of cattle poisoning on rangelands in the western United States.[67] Larkspur is more common in high-elevation areas, and many ranchers delay moving cattle onto such ranges until late summer when the toxicity of the plants is reduced.[68] Death is through cardiotoxic and neuromuscular blocking effects, and can occur within a few hours of ingestion.[69] All parts of the plant contain various diterpenoid alkaloids, typified by methyllycaconitine, and are very poisonous.[66]

Uses

[edit]The juice of the flowers, particularly D. consolida, mixed with alum, gives a blue ink.[70]

All plant parts are poisonous in large doses, especially the seeds, that contain up to 1.4% of alkaloids.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ Warnock, Michael J. (1997). "Delphinium". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 3. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- ^ a b c Wiese, Karen (2013). Sierra Nevada Wildflowers: A Field Guide To Common Wildflowers And Shrubs Of The Sierra Nevada, Including Yosemite, Sequoia, And Kings Canyon National Parks (2nd ed.). Falcon Guides. p. 52. ISBN 978-0762780341.

- ^ a b RHS A-Z encyclopedia of garden plants. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. 2008. p. 1136. ISBN 978-1405332965.

- ^ Jabbour, F.; Renner, S. S. (2011). "Consolida and Aconitella are an annual clade of Delphinium (Ranunculaceae) that diversified in the Mediterranean basin and the Irano-Turanian region". Taxon. 60 (4): 1029–1040. doi:10.1002/tax.604007.

- ^ Gledhill, D. (2008). The Names of Plants (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511480232. OCLC 348190404.

- ^ Bailly, Anatole (1981-01-01). Abrégé du dictionnaire grec français. Paris: Hachette. ISBN 978-2010035289. OCLC 461974285.

- ^ Bailly, Anatole. "delphinium". 'Abrégé du dictionnaire grec-français. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2017 – via Tabularium.

- ^ Dioscorides, P. (1829). Sprengel, K.P.J. (ed.). Pedanii Dioscoridis Anazarbei De materia medica libri quinque. Vol. Tomus Primus. Leipzig: Knobloch. pp. 420–421.

Flos albae violae similis, purpurascens, delphinorum effigie, unde et nomen adepta est planta.

- ^ a b Taylor, Ronald J. (1994) [1992]. Sagebrush Country: A Wildflower Sanctuary (rev. ed.). Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Pub. Co. p. 36. ISBN 0-87842-280-3. OCLC 25708726.

- ^ a b Warnock, Michael J. (1993). "Delphinium". In Hickman, James C. (ed.). The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California. University and Jepson Herbaria. Retrieved 2012-12-08.

- ^ "How To Plant, Grow, And Care For Delphinium Plant Perennial Flowers". www.plantgardener.com. 2024-05-06. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ Jabbour, Florian; Renner, Susanne (2011). "Resurrection of the genus Staphisagria J. Hill, sister to all the other Delphinieae (Ranunculaceae)". PhytoKeys (7): 21–6. Bibcode:2011PhytK...7...21J. doi:10.3897/phytokeys.7.2010. ISSN 1314-2003. PMC 3261041. PMID 22287922.

- ^ Jabbour, Florian; Renner, Susanne S. (2012). "A phylogeny of Delphinieae (Ranunculaceae) shows that Aconitum is nested within Delphinium and that Late Miocene transition to long life cycles in the Himalayas and Southwest China coincide with bursts in diversification". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 62 (3): 928–942. Bibcode:2012MolPE..62..928J. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.12.005. PMID 22182994.

- ^ Wang, Wei; Liu, Yang; Yu, Sheng-Xiang; Gai, Tian-Gang; Chen, Zhi-Duan (2013). "Gymnaconitum, a new genus of Ranunculaceae endemic to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau". Taxon. 62 (4): 713–722. doi:10.12705/624.10. Archived from the original on 2019-10-23. Retrieved 2019-09-12.

- ^ a b Jabbour, Florian; Renner, Susanne S. (March 2012). "A phylogeny of Delphinieae (Ranunculaceae) shows that Aconitum is nested within Delphinium and that Late Miocene transitions to long life cycles in the Himalayas and Southwest China coincide with bursts in diversification". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 62 (3): 928–942. Bibcode:2012MolPE..62..928J. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.12.005. PMID 22182994.

- ^ a b "Delphinium (Pacific Hybrids)". Plant Finder. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- ^ Rindels, Sherry (2013). "Delphiniums" (PDF). Revised by Richard Jauron, illustrations by Susan Aldworth. Iowa State Cooperative Extension.

- ^ a b "History of Delphiniums in cultivation". Dowdeswell's Delphiniums. Archived from the original on 2013-02-08. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ Bassett, David (2006). Delphiniums. United Kingdom: Batsford. p. 160. ISBN 978-0713490022.

- ^ "Growing Delphiniums from seed and caring for them". Dowdeswell's Delphiniums Ltd. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "Hybrid Delphiniums plant review". Timber Press. 2011-01-28. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ "Meet the 'Delphinium Dad' Whose Yorkshire Collection Has National Plant Collection Status". Living North.

- ^ "UK's Largest Delphinium Collection Awarded National Plant Collection Status". thedirt.news. August 29, 2024.

- ^ "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 29. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Atholl'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Blue Dawn'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Blue Nile'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Bruce'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Can-can'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Centurion Sky Blue'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Cherub'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Clifford Sky'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Conspicuous'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Elisabeth Sahin'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Elizabeth Cook'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Emily Hawkins'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Faust'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Fenella'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Foxhill Nina'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Galileo'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Holly Cookland Wilkins'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Jill Curley'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Kennington Classic'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Kestrel'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Langdon's Blue Lagoon'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Langdon's Pandora'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Lilian Bassett'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Lord Butler'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Lucia Sahin'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Margaret'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Michael Ayres'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Min'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Olive Poppleton'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Oliver'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Our Deb'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Purple Velvet'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Raymond Lister'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Rosemary Brock'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium × cultorum 'Rosy Future'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Spindrift'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Sungleam'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Sunkissed'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Sweethearts'". RHS Plantfinder. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Tiddles'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Delphinium 'Walton Gemstone'". RHS Plant Selector. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ a b Olsen, J. D.; Manners, G. D.; Pelletier, S. W. (1990). "Poisonous properties of larkspur (Delphinium spp.)". Collectanea Botanica. 19. Barcelona: 141–151. doi:10.3989/collectbot.1990.v19.122.

- ^ "Larkspur Fact Sheet". Logan, Utah: United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Poisonous Plant Research.

- ^ "Reducing Losses Due to Tall Larkspur Poisoning" (PDF). Utah State University.

- ^ Smith, Bradford (2002). Large Animal Internal Medicine (3rd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-323-00946-1.

- ^ Figuier, L. (1867). The Vegetable World, Being a History of Plants. Harvard University. p. 396.

External links

[edit]- General Nomenclature in GRIN: GRIN: Species in the genus Delphinium — with links by species for information + synonyms.

- USDA-ARS: Larkspur—Delphinium spp. Fact Sheet — native U.S. species and grazing toxicity.

- MBG—Kemper Center for Home Gardening: Delphinium "Pacific Giant Hybrids" — horticultural information.

- Dowdeswell's Ltd: "Growing New Millennium Delphiniums in the U.S. & Canada" — horticultural information.

.tif/lossless-page1-232px-Delphinium_elatum_var._palmatifidum_as_Delphinium_intermedium_var._palmatifidum_by_S._A._Drake._Edwards's_Botanical_Register_vol._24,_t._38_(1838).tif.png)

.tif/lossless-page1-1238px-Delphinium_elatum_var._palmatifidum_as_Delphinium_intermedium_var._palmatifidum_by_S._A._Drake._Edwards's_Botanical_Register_vol._24,_t._38_(1838).tif.png)