Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

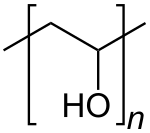

Polyvinyl alcohol

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

PVOH; Poly(Ethenol), Ethenol, homopolymer; PVA; Polyviol; Vinol; Alvyl; Alcotex; Covol; Gelvatol; Lemol; Mowiol; Mowiflex, Alcotex, Elvanol, Gelvatol, Lemol, Nelfilcon A, Polyviol und Rhodoviol

| |

| Identifiers | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.121.648 |

| E number | E1203 (additional chemicals) |

| KEGG | |

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| (C2H4O)x | |

| Density | 1.19–1.31 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 200 °C (392 °F; 473 K) |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.477 @ 632 nm[1] |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 79.44 °C (174.99 °F; 352.59 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

14,700 mg/kg (mouse) |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVOH, PVA, or PVAl) is a water-soluble synthetic polymer. It has the idealized formula [CH2CH(OH)]n. It is used in papermaking, textile warp sizing, as a thickener and emulsion stabilizer in polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) adhesive formulations, in a variety of coatings, and 3D printing. It is colourless (white) and odorless. It is commonly supplied as beads or as solutions in water.[2][3] Without an externally added crosslinking agent, PVA solution can be gelled through repeated freezing-thawing, yielding highly strong, ultrapure, biocompatible hydrogels which have been used for a variety of applications such as vascular stents, cartilages, contact lenses, etc.[4]

Although polyvinyl alcohol is often referred to by the acronym PVA, more generally PVA refers to polyvinyl acetate, which is commonly used as a wood adhesive and sealer.

Uses

[edit]PVA is used in a variety of medical applications because of its biocompatibility, low tendency for protein adhesion, and low toxicity. Specific uses include cartilage replacements, contact lenses, laundry detergent pods and eye drops.[5] Polyvinyl alcohol is used as an aid in suspension polymerizations. Its largest application in China is its use as a protective colloid to make PVAc dispersions. In Japan its major use is the production of Vinylon fiber.[6] This fiber is also manufactured in North Korea for self-sufficiency reasons, because no oil is required to produce it. Another application is photographic film.[7]

PVA-based polymers are used widely in additive manufacturing. For example, 3D printed oral dosage forms demonstrate great potential in the pharmaceutical industry. It is possible to create drug-loaded tablets with modified drug-release characteristics where PVA is used as a binder substance.[8]

Medically, PVA-based microparticles have received FDA 510(k) approval to be used as embolisation particles to be used for peripheral hypervascular tumors.[9] It may also used as the embolic agent in a Uterine Fibroid Embolectomy (UFE).[10] In biomedical engineering research, PVA has also been studied for cartilage, orthopaedic applications,[11] and potential materials for vascular graft.[12]

PVA is commonly used in household sponges that absorb more water than polyurethane sponges.[citation needed]

PVA may be used as an adhesive during preparation of stool samples for microscopic examination in pathology.[13]

Polyvinyl acetals

[edit]Polyvinyl acetals are prepared by treating PVA with aldehydes. Butyraldehyde and formaldehyde afford polyvinyl butyral (PVB) and polyvinyl formal (PVF), respectively. Preparation of polyvinyl butyral is the largest use for polyvinyl alcohol in the US and Western Europe.

Preparation

[edit]Unlike most vinyl polymers, PVA is not prepared by polymerization of the corresponding monomer, since the monomer, vinyl alcohol, is thermodynamically unstable with respect to its tautomerization to acetaldehyde. Instead, PVA is prepared by hydrolysis of polyvinyl acetate,[2] or sometimes other vinyl ester-derived polymers with formate or chloroacetate groups instead of acetate. The conversion of the polyvinyl esters is usually conducted by base-catalysed transesterification with ethanol:

- [CH2CH(OAc)]n + C2H5OH → [CH2CH(OH)]n + C2H5OAc

The properties of the polymer are affected by the degree of transesterification.

Worldwide consumption of polyvinyl alcohol was over one million metric tons in 2006.[6]

Structure and properties

[edit]PVA is an atactic material that exhibits crystallinity. In terms of microstructure, it is composed mainly of 1,3-diol linkages [−CH2−CH(OH)−CH2−CH(OH)−], but a few percent of 1,2-diols [−CH2−CH(OH)−CH(OH)−CH2−] occur, depending on the conditions for the polymerization of the vinyl ester precursor.[2]

Polyvinyl alcohol has excellent film-forming, emulsifying and adhesive properties. It is also resistant to oil, grease and solvents. It has high tensile strength and flexibility, as well as high oxygen and aroma barrier properties. However, these properties are dependent on humidity: water absorbed at higher humidity levels acts as a plasticiser, which reduces the polymer's tensile strength, but increases its elongation and tear strength.

Safety and environmental considerations

[edit]Polyvinyl alcohol is widely used, thus its toxicity and biodegradation are of interest. Tests showed that fish (guppies) are not harmed, even at a poly(vinyl alcohol) concentration of 500 mg/L of water.[2]

The biodegradability of PVA is affected by the molecular weight of the sample.[2] Aqueous solutions of PVA degrade faster, which is why PVA grades that are highly water-soluble tend to have a faster biodegradation.[14] Not all PVA grades are readily biodegradable, but studies show that high water-soluble PVA grades such as the ones used in detergents can be readily biodegradable according to OECD screening test conditions.[15]

Orally administered PVA is relatively harmless.[16] The safety of polyvinyl alcohol is based on some of the following observations:[16]

- The acute oral toxicity of polyvinyl alcohol is very low, with LD(50)s in the range of 15-20 g/kg;

- Orally administered PVA is very poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract;

- PVA does not accumulate in the body when administered orally;

- Polyvinyl alcohol is not mutagenic or clastogenic

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schnepf MJ, Mayer M, Kuttner C, et al. (July 2017). "Nanorattles with tailored electric field enhancement". Nanoscale. 9 (27): 9376–9385. doi:10.1039/C7NR02952G. hdl:10067/1447970151162165141. PMID 28656183.

- ^ a b c d e Hallensleben ML (2000). "Polyvinyl Compounds, Others". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_743. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Tang X, Alavi S (2011). "Recent Advances in Starch, Polyvinyl Alcohol Based Polymer Blends, Nanocomposites and Their Biodegradability". Carbohydrate Polymers. 85: 7–16. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.01.030.

- ^ Adelnia, Hossein; Ensandoost, Reza; Shebbrin Moonshi, Shehzahdi; et al. (2022-02-05). "Freeze/thawed polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels: Present, past and future". European Polymer Journal. 164 110974. Bibcode:2022EurPJ.16410974A. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2021.110974. hdl:10072/417476. ISSN 0014-3057. S2CID 245576810.

- ^ Baker MI, Walsh SP, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD (July 2012). "A review of polyvinyl alcohol and its uses in cartilage and orthopedic applications". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 100 (5): 1451–7. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.32694. PMID 22514196.

- ^ a b SRI Consulting CEH Report Polyvinyl Alcohol, published March 2007, abstract retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ Lampman, Steve, ed. (2003). "Effects of Composition, Processing, and Structure on Properties of Engineering Plastics". Characterization and Failure Analysis of Plastics. ASM International. p. 29. doi:10.31399/asm.tb.cfap.t69780028. ISBN 978-0-87170-789-5.

- ^ Xu X, Zhao J, Wang M, et al. (August 2019). "3D Printed Polyvinyl Alcohol Tablets with Multiple Release Profiles". Scientific Reports. 9 (1) 12487. Bibcode:2019NatSR...912487X. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-48921-8. PMC 6713737. PMID 31462744.

- ^ "Contour™ - Brief Summary". www.bostonscientific.com. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ Siskin GP. Cho KJ (ed.). "Uterine Fibroid Embolization and Imaging". Medscape. WebMD LLC. Archived from the original on 2015-03-04.

- ^ Baker, Maribel I.; Walsh, Steven P.; Schwartz, Zvi; Boyan, Barbara D. (July 2012). "A review of polyvinyl alcohol and its uses in cartilage and orthopedic applications". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 100B (5): 1451–1457. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.32694. PMID 22514196.

- ^ Chaouat, Marc; Le Visage, Catherine; Baille, Wilms E.; Escoubet, Brigitte; Chaubet, Frédéric; Mateescu, Mircea Alexandru; Letourneur, Didier (2008-10-09). "A Novel Cross-linked Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) for Vascular Grafts". Advanced Functional Materials. 18 (19): 2855–2861. doi:10.1002/adfm.200701261. S2CID 42332293.

- ^ Jensen, B.; Kepley, W.; Guarner, J.; Anderson, K.; Anderson, D.; Clairmont, J.; De l'aune, W.; Austin, E.H.; Austin, G.E. (2000). "Comparison of Polyvinyl Alcohol Fixative with Three Less Hazardous Fixatives for Detection and Identification of Intestinal Parasites". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 38 (4): 1592–1598. doi:10.1128/jcm.38.4.1592-1598.2000. PMC 86497. PMID 10747149.

- ^ Kawai F, Hu X (August 2009). "Biochemistry of microbial polyvinyl alcohol degradation". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 84 (2): 227–37. doi:10.1007/s00253-009-2113-6. PMID 19590867. S2CID 25068302.

- ^ Byrne, Dominic, Boeije, Geert, Croft, Ian, Hüttmann, Gerd, Luijkx, Gerard, Meier, Frank, Parulekar, Yash and Stijntjes, Gerard. "Biodegradability of Polyvinyl Alcohol Based Film Used for Liquid Detergent Capsules: Biologische Abbaubarkeit der für Flüssigwaschmittelkapseln verwendeten Folie auf Polyvinylalkoholbasis." Tenside Surfactants Detergents, vol. 58, no. 2, 2021, pp. 88-96. https://doi.org/10.1515/tsd-2020-2326

- ^ a b DeMerlis, C. C.; Schoneker, D. R. (March 2003). "Review of the oral toxicity of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 41 (3): 319–326. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00258-2. ISSN 0278-6915. PMID 12504164.

External links

[edit]Polyvinyl alcohol

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and basic characteristics

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), also known as polyethenol, is a water-soluble synthetic polymer produced by the hydrolysis of polyvinyl acetate, with the idealized repeating unit -[CH₂CH(OH)]ₙ-. [3] This process replaces acetate groups with hydroxyl groups, yielding a material that is odorless, tasteless, and appears as a white to cream-colored granular powder. [3] PVA cannot be synthesized directly via polymerization of vinyl alcohol, as the monomer is unstable and spontaneously tautomerizes to acetaldehyde under standard conditions. [9] As a polyol, PVA contains multiple hydroxyl (-OH) groups along its chain, which confer unique hydrophilic properties and enable hydrogen bonding, setting it apart from other vinyl polymers such as polyethylene (-[CH₂CH₂]ₙ-), which is hydrophobic and insoluble in water due to the absence of polar functional groups. This polarity makes PVA highly versatile as a water-soluble binder and stabilizer in various formulations. [6] Key characteristics of PVA include substantial tensile strength, flexibility, and excellent emulsifying capabilities, arising from its ability to form stable films and interact with both aqueous and non-aqueous phases. [6][10] Commercial grades typically exhibit degrees of polymerization from 500 to 5000, corresponding to molecular weights of approximately 20,000 to 200,000, and degrees of hydrolysis ranging from 88% to 99%, which influence solubility, viscosity, and crystallinity. [11][3]Historical development

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was first synthesized in 1924 by German chemists Willy O. Herrmann and Wolfram Haehnel through the hydrolysis of polyvinyl acetate using potassium hydroxide in ethanol, marking the initial preparation of this water-soluble polymer.[3] This discovery laid the foundation for PVA's development, though early efforts focused on overcoming its high water solubility for practical applications. Herrmann and Haehnel filed initial patents for PVA production processes in the mid-1920s, with subsequent advancements in Germany exploring its potential in adhesives and coatings, but commercialization remained limited due to technical challenges.[2] In the 1930s, PVA saw its first significant commercial breakthrough in the United States, where DuPont introduced the product under the trade name Elvanol, targeting uses in textiles, paper sizing, and adhesives.[12] This period aligned with growing demand for synthetic materials amid industrial expansion, enabling PVA's entry into global markets despite wartime disruptions. By the late 1930s, production scaled up, with Elvanol establishing PVA as a versatile resin in manufacturing.[13] Post-World War II, PVA production surged in the 1950s and 1960s, driven by rising needs in textiles and adhesives; Japan led this expansion, with Kuraray commercializing PVA fibers (Vinylon) in 1950—the world's first synthetic PVA fiber—for applications in clothing and industrial fabrics.[14] Global output grew rapidly, supported by resumed operations in Europe and the U.S., as PVA's adhesive properties proved essential for wood bonding and packaging amid postwar reconstruction.[15] By the 1960s, production reflected widespread adoption in consumer and industrial sectors.[16] The evolution of PVA grades progressed from early low-hydrolysis variants (around 80-90% hydrolyzed), which offered better solubility for adhesives, to higher-hydrolysis types (over 98%) by the 1970s and 1980s, enabling specialized uses like high-strength films.[17] Pharmaceutical applications of PVA have developed with enhanced purity standards to meet regulatory requirements for excipients in drug formulations.[18] In the 2020s, sustainable production initiatives have gained prominence, with manufacturers like Kuraray and OCI supporting sustainable manufacturing processes to reduce environmental impact.[19] Concurrently, post-2010 shifts toward bio-based alternatives, such as starch-derived or biomass-composite polymers, have accelerated amid sustainability pressures in packaging and films, addressing the petroleum origins of PVA.[20] As of 2024, global PVA production reached approximately 1.4 million metric tons annually.[21] This timeline underscores PVA's transition from a novel synthetic to a cornerstone material, now evolving amid sustainability pressures.[22]Chemical Structure and Properties

Molecular composition

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a synthetic polymer characterized by its repeating monomer unit of -CH₂-CH(OH)-, resulting in the idealized chemical formula (C₂H₄O)ₙ, where n represents the degree of polymerization typically ranging from hundreds to thousands.[23] This linear structure consists of a carbon backbone with pendant hydroxyl groups, which arise from the polymerization process and subsequent modifications.[24] PVA is primarily produced through the partial or complete hydrolysis of polyvinyl acetate (PVAc), which has the repeating unit -CH₂-CH(OCOCH₃)-. The hydrolysis reaction involves the cleavage of ester bonds, replacing acetate groups with hydroxyl groups, as represented by the equation: This process, often catalyzed by alkali or acid in methanolic solution, allows control over the degree of hydrolysis, influencing the final polymer composition.[25][3] The standard structure of PVA features head-to-tail linkages, where the hydroxyl-bearing carbon of one monomer connects to the methylene carbon of the next, forming a predominantly atactic configuration with no regular stereoregularity along the chain. This atactic nature stems from the free-radical polymerization of vinyl acetate precursor, leading to random placement of hydroxyl groups relative to the chain axis. The degree of hydrolysis, typically 80-99% for commercial grades, determines the proportion of residual acetate groups, which can introduce slight comonomer-like variations and affect chain regularity.[24][26] While PVA is generally linear, structural variations include possible branching from side reactions during polymerization of the precursor, and crosslinking can be induced post-synthesis through chemical agents targeting the hydroxyl groups. Syndiotactic forms, with higher regularity in hydroxyl placement, are achievable via advanced methods such as polymerization of vinyl trifluoroacetate followed by hydrolysis, yielding syndiotactic diad contents up to 69%.[27][28] Tacticity and sequence distributions in PVA are confirmed through nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, particularly ¹H and ¹³C NMR, which resolve triad (mm, mr, rr) and higher-order configurations based on chemical shift differences in the methine and methylene protons or carbons. Recent studies in the 2020s have utilized advanced NMR and scattering techniques to elucidate PVA's nanostructure, revealing self-organized dissipative structures in solution that influence chain folding and fibril formation at the nanoscale.[26][29]Physical and chemical properties

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) exhibits a range of physical properties that make it suitable for various material applications. Its density typically ranges from 1.19 to 1.31 g/cm³, depending on the degree of hydrolysis and processing conditions.[30] PVA has a glass transition temperature of approximately 75–85 °C, above which it transitions from a glassy to a rubbery state, influencing its flexibility and processability.[31] The material decomposes before fully melting, with decomposition onset around 200 °C and a reported melting point of 180–230 °C for different grades, where fully hydrolyzed PVA shows higher thermal endurance than partially hydrolyzed variants.[32] PVA demonstrates high water solubility, particularly for lower molecular weight grades, dissolving up to 100 g/L at 20 °C, though solubility decreases with increasing hydrolysis degree and molecular weight.[30] Chemically, PVA's numerous hydroxyl groups enable strong intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding, which contributes to its excellent film-forming ability and adhesive properties.[33] This hydrogen bonding network also imparts resistance to oils, greases, and most hydrocarbon solvents, as the polar structure repels non-polar substances.[23] However, PVA is susceptible to degradation in strong acids or bases, where hydrolysis or swelling can disrupt the polymer chains, and it remains stable in weak acids, bases, and organic solvents under ambient conditions.[34] Aqueous solutions of PVA exhibit pseudoplastic behavior, with viscosities ranging from 4 to 50 cP for 4% solutions at 20 °C, varying by molecular weight and concentration; higher molecular weights yield more viscous solutions suitable for coating applications.[30] In terms of thermal stability, PVA undergoes dehydration at elevated temperatures above 200 °C, forming conjugated polyene structures through elimination of water molecules, which can lead to discoloration and chain scission.[35] This process enhances thermal degradation resistance up to approximately 380 °C for dehydrated forms but limits long-term exposure to high heat. Optically, PVA films are highly transparent, with refractive indices around 1.477 at 632 nm, due to the uniform amorphous and crystalline regions formed by hydrogen bonding.[36] Properties of PVA vary significantly by grade, particularly with molecular weight and hydrolysis degree, affecting mechanical and rheological performance. Higher molecular weights increase crystallinity, leading to tensile strengths of 20–80 MPa and elongations at break of 200–400% in films, with greater chain entanglement enhancing overall toughness and modulus.[37] For instance, low molecular weight PVA (around 20,000–50,000 g/mol) offers higher elongation but lower strength, while high molecular weight grades (above 100,000 g/mol) provide superior tensile properties.[38] In emerging 3D printing applications since the 2020s, PVA's rheological properties are critical, showing strong shear-thinning behavior where viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate (e.g., from 10^3 to 10 Pa·s under typical extrusion conditions), enabling precise filament deposition; temperature elevation to 180–200 °C further reduces melt viscosity for improved printability, though excessive heat risks degradation.[39]| Property | Typical Value | Influencing Factors | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 1.19–1.31 g/cm³ | Hydrolysis degree | [30] |

| Glass Transition Temperature | 75–85 °C | Molecular weight | [31] |

| Decomposition Temperature | >200 °C | Crystallinity | [32] |

| Water Solubility (low MW) | Up to 100 g/L at 20 °C | Hydrolysis degree | [30] |

| Solution Viscosity (4 wt%) | 4–50 cP at 20 °C | Molecular weight | [30] |

| Tensile Strength | 20–80 MPa | Molecular weight | [37] |

| Elongation at Break | 200–400% | Molecular weight | [38] |