Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Emotion classification

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Emotions |

|---|

|

Emotion classification is the means by which one may distinguish or contrast one emotion from another. It is a contested issue in emotion research and in affective science.

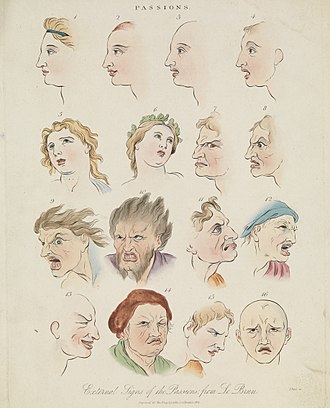

Emotions as discrete categories

[edit]In discrete emotion theory, all humans are thought to have an innate set of basic emotions that are cross-culturally recognizable. These basic emotions are described as "discrete" because they are believed to be distinguishable by an individual's facial expression and biological processes.[1] Theorists have conducted studies to determine which emotions are basic. A popular example is Paul Ekman and his colleagues' cross-cultural study of 1992, in which they concluded that the six basic emotions are anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise.[2] Ekman explains that there are particular characteristics attached to each of these emotions, allowing them to be expressed in varying degrees in a non-verbal manner.[3][4] Each emotion acts as a discrete category rather than an individual emotional state.[5]

Simplicity debate

[edit]Humans' subjective experience is that emotions are clearly recognizable in ourselves and others. This apparent ease of recognition has led to the identification of a number of emotions that are said to be basic, and universal among all people. However, a debate among experts has questioned this understanding of what emotions are. There has been recent discussion of the progression on the different views of emotion over the years.[6]

On "basic emotion" accounts, activation of an emotion, such as anger, sadness, or fear, is "triggered" by the brain's appraisal of a stimulus or event with respect to the perceiver's goals or survival. In particular, the function, expression, and meaning of different emotions are hypothesized to be biologically distinct from one another. A theme common to many basic emotions theories is that there should be functional signatures that distinguish different emotions: we should be able to tell what emotion a person is feeling by looking at his or her brain activity and/or physiology. Furthermore, knowledge of what the person is seeing or the larger context of the eliciting event should not be necessary to deduce what the person is feeling from observing the biological signatures.[5]

On "constructionist" accounts, the emotion a person feels in response to a stimulus or event is "constructed" from more elemental biological and psychological ingredients. Two hypothesized ingredients are "core affect" (characterized by, e.g., hedonic valence and physiological arousal) and conceptual knowledge (such as the semantic meaning of the emotion labels themselves, e.g., the word "anger"). A theme common to many constructionist theories is that different emotions do not have specific locations in the nervous system or distinct physiological signatures, and that context is central to the emotion a person feels because of the accessibility of different concepts afforded by different contexts.[7]

Dimensional models of emotion

[edit]For both theoretical and practical reasons, researchers define emotions according to one or more dimensions. In his 1649 philosophical treatise, The Passions of the Soul, Descartes defines and investigates the six primary passions (Wonder, love, hate, desire, joy, and sadness). In 1897, Wilhelm Max Wundt, the father of modern psychology, proposed that emotions can be described by three dimensions: "pleasurable versus unpleasurable", "arousing or subduing", and "strain or relaxation".[8] In 1954, Harold Schlosberg named three dimensions of emotion: "pleasantness–unpleasantness", "attention–rejection" and "level of activation".[9]

Dimensional models of emotion attempt to conceptualize human emotions by defining where they lie in two or three dimensions. Most dimensional models incorporate valence and arousal or intensity dimensions. Dimensional models of emotion suggest that a common and interconnected neurophysiological system is responsible for all affective states.[10] These models contrast theories of basic emotion, which propose that different emotions arise from separate neural systems.[10] Several dimensional models of emotion have been developed, though there are just a few that remain as the dominant models currently accepted by most.[11] The two-dimensional models that are most prominent are the circumplex model, the vector model, and the Positive Activation – Negative Activation (PANA) model.[11]

Circumplex model

[edit]

The circumplex model of emotion was developed by James Russell.[12] This model suggests that emotions are distributed in a two-dimensional circular space, containing arousal and valence dimensions. Arousal represents the vertical axis and valence represents the horizontal axis, while the center of the circle represents a neutral valence and a medium level of arousal.[11] In this model, emotional states can be represented at any level of valence and arousal, or at a neutral level of one or both of these factors. Circumplex models have been used most commonly to test stimuli of emotion words, emotional facial expressions, and affective states.[13]

Russell and Lisa Feldman Barrett describe their modified circumplex model as representative of core affect, or the most elementary feelings that are not necessarily directed toward anything. Different prototypical emotional episodes, or clear emotions that are evoked or directed by specific objects, can be plotted on the circumplex, according to their levels of arousal and pleasure.[14]

Vector model

[edit]

The vector model of emotion appeared in 1992.[16] This two-dimensional model consists of vectors that point in two directions, representing a "boomerang" shape. The model assumes that there is always an underlying arousal dimension, and that valence determines the direction in which a particular emotion lies. For example, a positive valence would shift the emotion up the top vector and a negative valence would shift the emotion down the bottom vector.[11] In this model, high arousal states are differentiated by their valence, whereas low arousal states are more neutral and are represented near the meeting point of the vectors. Vector models have been most widely used in the testing of word and picture stimuli.[13]

Positive activation – negative activation (P.A.N.A.) model

[edit]The positive activation – negative activation (P.A.N.A.) or "consensual" model of emotion, originally created by Watson and Tellegen in 1985,[17] suggests that positive affect and negative affect are two separate systems. Similar to the vector model, states of higher arousal tend to be defined by their valence, and states of lower arousal tend to be more neutral in terms of valence.[11] In the P.A.N.A. model, the vertical axis represents low to high positive affect and the horizontal axis represents low to high negative affect. The dimensions of valence and arousal lay at a 45-degree rotation over these axes.[17]

Plutchik's model

[edit]Robert Plutchik offers a three-dimensional model that is a hybrid of both basic-complex categories and dimensional theories. It arranges emotions in concentric circles where inner circles are more basic and outer circles more complex. Notably, outer circles are also formed by blending the inner circle emotions. Plutchik's model, as Russell's, emanates from a circumplex representation, where emotional words were plotted based on similarity.[18] There are numerous emotions, which appear in several intensities and can be combined in various ways to form emotional "dyads".[19][20][21][22][23]

PAD emotional state model

[edit]The PAD emotional state model is a psychological model developed by Albert Mehrabian and James A. Russell to describe and measure emotional states. PAD uses three numerical dimensions to represent all emotions.[24][25] The PAD dimensions are Pleasure, Arousal and Dominance.

- The Pleasure-Displeasure Scale measures how pleasant an emotion may be. For instance, both anger and fear are unpleasant emotions, and score high on the displeasure scale. However, joy is a pleasant emotion.[24]

- The Arousal-Nonarousal Scale measures how energized or soporific one feels. It is not the intensity of the emotion—for grief and depression can be low arousal intense feelings. While both anger and rage are unpleasant emotions, rage has a higher intensity or a higher arousal state. However boredom, which is also an unpleasant state, has a low arousal value.[24]

- The Dominance-Submissiveness Scale represents the controlling and dominant nature of the emotion. For instance, while both fear and anger are unpleasant emotions, anger is a dominant emotion, while fear is a submissive emotion.[24]

Criticisms

[edit]Cultural considerations

[edit]Ethnographic and cross-cultural studies of emotions have shown the variety of ways in which emotions differ with cultures. Because of these differences, many cross-cultural psychologists and anthropologists challenge the idea of universal classifications of emotions altogether. Cultural differences have been observed in the way in which emotions are valued, expressed, and regulated. The social norms for emotions, such as the frequency with or circumstances in which they are expressed, also vary drastically.[26][27] For example, the demonstration of anger is encouraged by Kaluli people, but condemned by Utku Inuit.[28]

The largest piece of evidence that disputes the universality of emotions is language. Differences within languages directly correlate to differences in emotion taxonomy. Languages differ in that they categorize emotions based on different components. Some may categorize by event types, whereas others categorize by action readiness. Furthermore, emotion taxonomies vary due to the differing implications emotions have in different languages.[26] That being said, not all English words have equivalents in all other languages and vice versa, indicating that there are words for emotions present in some languages but not in others.[29] Emotions such as the schadenfreude in German and saudade in Portuguese are commonly expressed in emotions in their respective languages, but lack an English equivalent.

Some languages do not differentiate between emotions that are considered to be the basic emotions in English. For instance, certain African languages have one word for both anger and sadness, and others for shame and fear. There is ethnographic evidence that even challenges the universality of the category "emotions" because certain cultures lack a specific word relating to the English word "emotions".[27]

Lists of emotions

[edit]Emotions are categorized into various affects, which correspond to the current situation.[30] An affect is the range of feeling experienced.[31] Both positive and negative emotions are needed in our daily lives.[32] Many theories of emotion have been proposed,[33] with contrasting views.[34]

Basic emotions

[edit]- William James in 1890 proposed four basic emotions: fear, grief, love, and rage, based on bodily involvement.[35]

- Paul Ekman identified six basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise.[36] Wallace V. Friesen and Phoebe C. Ellsworth worked with him on the same basic structure.[37] The emotions can be linked to facial expressions. In the 1990s, Ekman proposed an expanded list of basic emotions, including a range of positive and negative emotions that are not all encoded in facial muscles.[38] The newly included emotions are: amusement, contempt, contentment, embarrassment, excitement, guilt, pride in achievement, relief, satisfaction, sensory pleasure, and shame.[38]

- Richard and Bernice Lazarus in 1996 expanded the list to 15 emotions: aesthetic experience, anger, anxiety, compassion, depression, envy, fright, gratitude, guilt, happiness, hope, jealousy, love, pride, relief, sadness, and shame, in the book Passion and Reason.[39][40]

- Researchers[41] at University of California, Berkeley identified 27 categories of emotion: admiration, adoration, aesthetic appreciation, amusement, anger, anxiety, awe, awkwardness, boredom, calmness, confusion, craving, disgust, empathic pain, entrancement, excitement, fear, horror, interest, joy, nostalgia, relief, romance, sadness, satisfaction, sexual desire and surprise.[42] This was based on 2185 short videos intended to elicit a certain emotion. These were then modeled onto a "map" of emotions.[43]

Contrasting basic emotions

[edit]A 2009 review[44] of theories of emotion identifies and contrasts fundamental emotions according to three key criteria for mental experiences that:

- have a strongly motivating subjective quality like pleasure or pain;

- are a response to some event or object that is either real or imagined;

- motivate particular kinds of behavior.

The combination of these attributes distinguishes emotions from sensations, feelings and moods.

| Kind of emotion | Positive emotions | Negative emotions |

|---|---|---|

| Related to object properties | Interest, curiosity, enthusiasm | Alarm, panic |

| Attraction, desire, admiration | Aversion, disgust, revulsion | |

| Surprise, amusement | Indifference, habituation, boredom | |

| Future appraisal | Hope, excitement | Fear, anxiety, dread |

| Event-related | Gratitude, thankfulness | Anger, rage |

| Joy, elation, triumph, jubilation | Sorrow, grief | |

| Patience | Frustration, restlessness | |

| Contentment | Discontentment, disappointment | |

| Self-appraisal | Humility, modesty | Pride, arrogance |

| Social | Charity | Avarice, greed, miserliness, envy, jealousy |

| Sympathy | Cruelty | |

| Cathected | Love | Hate |

Emotion dynamics

[edit]Researchers distinguish several emotion dynamics, most commonly how intense (mean level), variable (fluctuations), inert (temporal dependency), instable (magnitude of moment-to-moment fluctuations), or differentiated someone's emotions are (the specificity of granularity of emotions), and whether and how an emotion augments or blunts other emotions.[45] Meta-analytic reviews show systematic developmental changes in emotion dynamics throughout childhood and adolescence and substantial between-person differences.[45]

HUMAINE's proposal for EARL

[edit]The emotion annotation and representation language (EARL) proposed by the Human-Machine Interaction Network on Emotion (HUMAINE) classifies 49 emotions.[46]

- Negative and forceful

- Anger

- Annoyance

- Contempt

- Disgust

- Irritation

- Negative and not in control

- Anxiety

- Embarrassment

- Fear

- Helplessness

- Powerlessness

- Worry

- Negative thoughts

- Doubt

- Envy

- Frustration

- Guilt

- Shame

- Negative and passive

- Agitation

- Positive and lively

- Amusement

- Delight

- Elation

- Excitement

- Happiness

- Joy

- Pleasure

- Caring

- Positive thoughts

- Pride

- Courage

- Hope

- Humility

- Satisfaction

- Trust

- Quiet positive

- Calmness

- Contentment

- Relaxation

- Relief

- Serenity

- Reactive

- Interest

- Politeness

- Surprise

Parrott's emotions by groups

[edit]A tree-structured list of emotions was described in Shaver et al. (1987),[47] and also featured in Parrott (2001).[48]

| Primary emotion | Secondary emotion | Tertiary emotion |

|---|---|---|

| Love | Affection | Adoration · Fondness · Liking · Attraction · Caring · Tenderness · Compassion · Sentimentality |

| Lust/Sexual desire | Desire · Passion · Infatuation | |

| Longing | Longing | |

| Joy | Cheerfulness | Amusement · Bliss · Gaiety · Glee · Jolliness · Joviality · Joy · Delight · Enjoyment · Gladness · Happiness · Jubilation · Elation · Satisfaction · Ecstasy · Euphoria |

| Zest | Enthusiasm · Zeal · Excitement · Thrill · Exhilaration | |

| Contentment | Pleasure | |

| Pride | Triumph | |

| Optimism | Eagerness · Hope | |

| Enthrallment | Enthrallment · Rapture | |

| Relief | Relief | |

| Surprise | Surprise | Amazement · Astonishment |

| Anger | Irritability | Aggravation · Agitation · Annoyance · Grouchy · Grumpy · Crosspatch |

| Exasperation | Frustration | |

| Rage | Anger · Outrage · Fury · Wrath · Hostility · Ferocity · Bitterness · Hatred · Scorn · Spite · Vengefulness · Dislike · Resentment | |

| Disgust | Revulsion · Contempt · Loathing | |

| Envy | Jealousy | |

| Torment | Torment | |

| Sadness | Suffering | Agony · Anguish · Hurt |

| Sadness | Depression · Despair · Gloom · Glumness · Unhappiness · Grief · Sorrow · Woe · Misery · Melancholy | |

| Disappointment | Dismay · Displeasure | |

| Shame | Guilt · Regret · Remorse | |

| Neglect | Alienation · Defeatism · Dejection · Embarrassment · Homesickness · Humiliation · Insecurity · Insult · Isolation · Loneliness · Rejection | |

| Sympathy | Pity · Mono no aware · Sympathy | |

| Fear | Horror | Alarm · Shock · Fear · Fright · Horror · Terror · Panic · Hysteria · Mortification |

| Nervousness | Anxiety · Suspense · Uneasiness · Apprehension (fear) · Worry · Distress · Dread |

Plutchik's wheel of emotions

[edit]In 1980, Robert Plutchik diagrammed a wheel of eight emotions: joy, trust, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger and anticipation, inspired by his Ten Postulates.[49][50] Plutchik also theorized twenty-four "Primary", "Secondary", and "Tertiary" dyads (feelings composed of two emotions).[51][52][53][54][55][56][57] The wheel emotions can be paired in four groups:

- Primary dyad = one petal apart = Love = Joy + Trust

- Secondary dyad = two petals apart = Envy = Sadness + Anger

- Tertiary dyad = three petals apart = Shame = Fear + Disgust

- Opposite emotions = four petals apart = Anticipation ∉ Surprise

There are also triads, emotions formed from 3 primary emotions, though Plutchik never describes in any detail what the triads might be.[58] This leads to a combination of 24 dyads and 32 triads, making 56 emotions at 1 intensity level.[59] Emotions can be mild or intense;[60] for example, distraction is a mild form of surprise, and rage is an intense form of anger. The kinds of relation between each pair of emotions are:

| Mild emotion | Mild opposite | Basic emotion | Basic opposite | Intense emotion | Intense opposite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serenity | Pensiveness, Gloominess | Joy, Cheerfulness | Sadness, Dejection | Ecstasy, Elation | Grief, Sorrow |

| Acceptance, Tolerance | Boredom, Dislike | Trust | Disgust, Aversion | Admiration, Adoration | Loathing, Revulsion |

| Apprehension, Dismay | Annoyance, Irritation | Fear, Fright | Anger, Hostility | Terror, Panic | Rage, Fury |

| Distraction, Uncertainty | Interest, Attentiveness | Surprise | Anticipation, Expectancy | Amazement, Astonishment | Vigilance |

| Human feelings | Emotions | Opposite feelings | Emotions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism, Courage | Anticipation + Joy | Disapproval, Disappointment | Surprise + Sadness |

| Hope, Fatalism | Anticipation + Trust | Unbelief, Shock | Surprise + Disgust |

| Anxiety, Dread | Anticipation + Fear | Outrage, Hate | Surprise + Anger |

| Love, Friendliness | Joy + Trust | Remorse, Misery | Sadness + Disgust |

| Guilt, Excitement | Joy + Fear | Envy, Sullenness | Sadness + Anger |

| Delight, Doom | Joy + Surprise | Pessimism | Sadness + Anticipation |

| Submission, Modesty | Trust + Fear | Contempt, Scorn | Disgust + Anger |

| Curiosity | Trust + Surprise | Cynicism | Disgust + Anticipation |

| Sentimentality, Resignation | Trust + Sadness | Morbidness, Derisiveness | Disgust + Joy |

| Awe, Alarm | Fear + Surprise | Aggressiveness, Vengeance | Anger + Anticipation |

| Despair | Fear + Sadness | Pride, Victory | Anger + Joy |

| Shame, Prudishness | Fear + Disgust | Dominance | Anger + Trust |

| Human feelings | Emotions |

|---|---|

| Bittersweetness | Joy + Sadness |

| Ambivalence | Trust + Disgust |

| Frozenness | Fear + Anger |

| Confusion | Surprise + Anticipation |

Similar emotions in the wheel are adjacent to each other.[61] Anger, Anticipation, Joy, and Trust are positive in valence, while Fear, Surprise, Sadness, and Disgust are negative in valence. Anger is classified as a "positive" emotion because it involves "moving toward" a goal,[62] while surprise is negative because it is a violation of someone's territory.[63] The emotion dyads each have half-opposites and exact opposites:[64]

| + | Sadness | Joy |

|---|---|---|

| Anticipation | Pessimism | Optimism |

| Surprise | Disapproval | Delight |

| + | Disgust | Trust |

|---|---|---|

| Joy | Morbidness | Love |

| Sadness | Remorse | Sentimentality |

| + | Fear | Anger |

|---|---|---|

| Trust | Submission | Dominance |

| Disgust | Shame | Contempt |

| + | Surprise | Anticipation |

|---|---|---|

| Anger | Outrage | Aggressiveness |

| Fear | Awe | Anxiety |

| + | Surprise | Anticipation |

|---|---|---|

| Trust | Curiosity | Hope |

| Disgust | Unbelief | Cynicism |

| + | Fear | Anger |

|---|---|---|

| Joy | Guilt | Pride |

| Sadness | Despair | Envy |

Six emotion axes

[edit]MIT researchers [65] published a paper titled "An Affective Model of Interplay Between Emotions and Learning: Reengineering Educational Pedagogy—Building a Learning Companion" that lists six axes of emotions with different opposite emotions, and different emotions coming from ranges.[65]

| Axis | -1.0 | -0.5 | 0 | 0 | +0.5 | +1.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety – Confidence | Anxiety | Worry | Discomfort | Comfort | Hopeful | Confident |

| Boredom – Fascination | Ennui | Boredom | Indifference | Interest | Curiosity | Intrigue |

| Frustration – Euphoria | Frustration | Puzzlement | Confusion | Insight | Enlightenment | Epiphany |

| Dispirited – Encouraged | Dispirited | Disappointed | Dissatisfied | Satisfied | Thrilled | Enthusiastic |

| Terror – Enchantment | Terror | Dread | Apprehension | Calm | Anticipatory | Excited |

| Humiliation – Pride | Humiliated | Embarrassed | Self-conscious | Pleased | Satisfied | Proud |

They also made a model labeling phases of learning emotions.[65]

| Negative Affect | Positive Affect | |

|---|---|---|

| Constructive Learning | Disappointment, Puzzlement, Confusion | Awe, Satisfaction, Curiosity |

| Un-learning | Frustration, Discard, | Hopefulness, Fresh research |

The Book of Human Emotions

[edit]Tiffany Watt Smith listed 154 different worldwide emotions and feelings.[66]

- A

- B

- C

- Calm

- Carefree

- Cheerfulness

- Cheesed (off)

- Claustrophobia

- Collywobbles, the

- Comfort

- Compassion

- Compersion

- Confidence

- Contempt

- Contentment

- Courage

- Curiosity

- Cyberchondria

- D

- Delight

- Dépaysement

- Desire

- Despair

- Disappear, the desire to

- Disappointment

- Disgruntlement

- Disgust

- Dismay

- Dolce far niente

- Dread

- E

- Ecstasy

- Embarrassment

- Empathy

- Envy

- Euphoria

- Exasperation

- Excitement

- F

- Fago

- Fear

- Feeling good (about yourself)

- Formal feeling, a

- Fraud, feeling like a

- Frustration

- G

- Gezelligheid

- Gladsomeness

- Glee

- Gratitude

- Greng jai

- Grief

- Guilt

- H

- Han

- Happiness

- Hatred

- Heebie-Jeebies, the

- Hiraeth

- Hoard, the urge to

- Homefulness

- Homesickness

- Hopefulness

- Huff, in a

- Humble, feeling

- Humiliation

- Hunger

- Hwyl

- I

- Ijirashi

- Ikstuarpok

- Ilinx

- Impatience

- Indignation

- Inhabitiveness

- Insulted, feeling

- Irritation

- J

- Jealousy

- Joy

- K

- L

- M

- Malu

- Man

- Matutolypea

- Mehameha

- Melancholy

- Miffed, a bit

- Mono no aware

- Morbid curiosity

- Mudita

- N

- Nakhes

- Nginyiwarrarringu

- Nostalgia

- O

- Oime

- Overwhelmed, feeling

- P

- Panic

- Paranoia

- Perversity

- Peur des espaces

- Philoprogenitiveness

- Pique, a fit of

- Pity

- Postal, going

- Pride

- Pronoia

- R

- Rage

- Regret

- Relief

- Reluctance

- Remorse

- Reproachfulness

- Resentment

- Ringxiety

- Rivalry

- Road rage

- Ruinenlust

- S

- T

- Technostress

- Terror

- Torschlusspanik

- Toska

- Triumph

- U

- Umpty

- Uncertainty

- V

- Vengefulness

- Vergüenza ajena

- Viraha

- Vulnerability

- W

- Wanderlust

- Warm glow

- Wonder

- Worry

- Z

Mapping facial expressions

[edit]Scientists map twenty-one different facial emotions[68][69] expanded from Paul Ekman's six basic emotions of anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise:

| Fearful | Angry | Surprised | Disgusted | ||

| Happy | Happily Surprised | Happily Disgusted | |||

| Sad | Sadly Fearful | Sadly Angry | Sadly Surprised | Sadly Disgusted | |

| Appalled | Fearfully Angry | Fearfully Surprised | Fearfully Disgusted | ||

| Awed | Angrily Surprised | Angrily Disgusted | |||

| Hatred | Disgustedly Surprised |

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Ekman, P. (1972). Universals and cultural differences in facial expression of emotion. In J. Cole (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press: pp. 207–283.

- Ekman, P. (1992). "An argument for basic emotions". Cognition and Emotion. 6 (3): 169–200. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.1984. doi:10.1080/02699939208411068.

- Ekman, P. (1999). Basic Emotions. In T. Dalgleish and T. Power (Eds.) The Handbook of Cognition and Emotion Pp. 45–60. Sussex, U.K.: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Fontaine, J.; Scherer, KR; Roesch, EB; Ellsworth, PC (2007). "The world of emotions is not two-dimensional". Psychological Science. 18 (12): 1050–1057. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1031.3706. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02024.x. PMID 18031411. S2CID 1779061.

- Koelsch, S.; Jacobs, AM.; Menninghaus, W.; Liebal, K.; Klann-Delius, G.; von Scheve, C.; Gebauer, G. (2015). "The quartet theory of human emotions: An integrative and neurofunctional model". Phys Life Rev. 13: 1–27. Bibcode:2015PhLRv..13....1K. doi:10.1016/j.plrev.2015.03.001. PMID 25891321.

- Prinz, J. (2004). Gut Reactions: A Perceptual Theory of Emotions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309362

- Sugu, Dana; Chaterjee, Amita (2010). "Flashback: Reshuffling Emotions". International Journal on Humanistic Ideology. 3 (1). Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-11-11.

- Russell, J.A. (1979). "Affective space is bipolar". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37 (3): 345–356. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.3.345. S2CID 17557962.

- Russell, J.A. (1991). "Culture and the categorization of emotions" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 110 (3): 426–50. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.426. PMID 1758918. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Colombetti, Giovanna (August 2009). "From affect programs to dynamical discrete emotions". Philosophical Psychology. 22 (4): 407–425. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.728.9666. doi:10.1080/09515080903153600. S2CID 40157414.

- ^ Ekman, Paul (January 1992). "Facial Expressions of Emotion: New Findings, New Questions". Psychological Science. 3 (1): 34–38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00253.x. S2CID 9274447.

- ^ Bąk, Halszka (2023-12-01). "Issues in the translation equivalence of basic emotion terms". Ampersand. 11 100128. doi:10.1016/j.amper.2023.100128. ISSN 2215-0390.

- ^ Elfenbein, Hillary Anger; Ambady, Nalini (2003-10-01). "Universals and Cultural Differences in Recognizing Emotions". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 12 (5): 159–164. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01252. ISSN 0963-7214. S2CID 262438746.

- ^ a b Ekman, Paul (1992). "An Argument for Basic Emotions". Cognition and Emotion. 6 (3/4): 169–200. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.1984. doi:10.1080/02699939208411068.

- ^ Gendron, Maria; Barrett, Lisa Feldman (October 2009). "Reconstructing the Past: A Century of Ideas About Emotion in Psychology". Emotion Review. 1 (4): 316–339. doi:10.1177/1754073909338877. PMC 2835158. PMID 20221412.

- ^ Barrett, Lisa Feldman (2006). "Solving the Emotion Paradox: Categorization and the Experience of Emotion". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 10 (1): 20–46. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_2. PMID 16430327. S2CID 7750265.

- ^ "Outlines of Psychology. (1897). In: Classics in the history of psychology". Archived from the original on 2001-02-24.

- ^ Schlosberg, H. (1954). "Three dimensions of emotion". Psychological Review. 61 (2): 81–8. doi:10.1037/h0054570. PMID 13155714. S2CID 27914497.

- ^ a b Posner, Jonathan; Russell, J.A.; Peterson, B. S. (2005). "The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology". Development and Psychopathology. 17 (3): 715–734. doi:10.1017/s0954579405050340. PMC 2367156. PMID 16262989.

- ^ a b c d e Rubin, D. C.; Talerico, J.M. (2009). "A comparison of dimensional models of emotion". Memory. 17 (8): 802–808. doi:10.1080/09658210903130764. PMC 2784275. PMID 19691001.

- ^ Russell, James (1980). "A circumplex model of affect". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 39 (6): 1161–1178. doi:10.1037/h0077714. hdl:10983/22919.

- ^ a b Remington, N. A.; Fabrigar, L. R.; Visser, P. S. (2000). "Re-examining the circumplex model of affect". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 79 (2): 286–300. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.286. PMID 10948981.

- ^ Russell, James; Feldman Barrett, Lisa (1999). "Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: dissecting the elephant". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 76 (5): 805–819. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.805. PMID 10353204.

- ^ Wilson, Graham; Dobrev, Dobromir; Brewster, Stephen A. (2016-05-07). "Hot Under the Collar: Mapping Thermal Feedback to Dimensional Models of Emotion" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. pp. 4838–4849. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858205. ISBN 978-1-4503-3362-7. S2CID 13051231.

- ^ Bradley, M. M.; Greenwald, M. K.; Petry, M.C.; Lang, P. J. (1992). "Remembering pictures: Pleasure and arousal in memory". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 18 (2): 379–390. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.18.2.379. PMID 1532823.

- ^ a b Watson, D.; Tellegen, A. (1985). "Toward a consensual structure of mood". Psychological Bulletin. 98 (2): 219–235. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.219. PMID 3901060.

- ^ Plutchik, R. "The Nature of Emotions". American Scientist. Archived from the original on July 16, 2001. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Plutchik, Robert (16 September 1991). The Emotions. University Press of America. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8191-8286-9. Retrieved 16 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Plutchik, R. "The Nature of Emotions". American Scientist. Archived from the original on July 16, 2001. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ "Robert Plutchik's Psychoevolutionary Theory of Basic Emotions" (PDF). Adliterate.com. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ^ Jonathan Turner (1 June 2000). On the Origins of Human Emotions: A Sociological Inquiry Into the Evolution of Human Affect. Stanford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8047-6436-0.

- ^ Atifa Athar; M. Saleem Khan; Khalil Ahmed; Aiesha Ahmed; Nida Anwar (June 2011). "A Fuzzy Inference System for Synergy Estimation of Simultaneous Emotion Dynamics in Agents". International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 2 (6).

- ^ a b c d Mehrabian, Albert (1980). Basic dimensions for a general psychological theory. Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain. pp. 39–53. ISBN 978-0-89946-004-8.

- ^ Bales, Robert Freed (2001). Social interaction systems: theory and measurement. Transaction Publishers. pp. 139–140. ISBN 978-0-7658-0872-1.

- ^ a b Mesquita, Batja; Nico Frijda (September 1992). "Cultural variations in emotions: a review". Psychological Bulletin. 112 (2): 179–204. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.179. PMID 1454891.

- ^ a b Russell, James (1991). "Culture and Categorization of Emotions" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 110 (3): 426–450. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.426. PMID 1758918. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Eid, Michael; Ed Diener (November 2001). "Norms for experiencing emotions in different cultures: Inter- and intranational differences". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 81 (5): 869–885. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.869. PMID 11708563.(subscription required)

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (September 1986). "Human Emotions: Universal or Culture-Specific?". American Anthropologist. 88 (3): 584–594. doi:10.1525/aa.1986.88.3.02a00030. JSTOR 679478.(subscription required)

- ^ Lisa Feldman Barrett (2006). "Solving the Emotion Paradox: Categorization and the Experience of Emotion". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 10 (1): 20–46. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_2. PMID 16430327. S2CID 7750265.

- ^ "Emotions and Moods" (PDF). Catalogue.pearsoned.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Parrott, W. Gerrod (27 January 2014). The Positive Side of Negative Emotions. Guilford Publications. ISBN 978-1-4625-1333-8. Retrieved 19 December 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Comparing The 5 Theories of Emotion – Brain Blogger". Mind. os–IX (34): 188–205. 1884. doi:10.1093/mind/os-IX.34.188. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Candland, Douglas (23 November 2017). Emotion. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-27026-2. Retrieved 23 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ James, William (1 April 2007). The Principles of Psychology. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60206-313-6. Retrieved 20 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Handel, Steven (2011-05-24). "Classification of Emotions". Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "Are There Basic Emotions?" (PDF). Paulekam.com. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ a b Ekman, Paul (1999), "Basic Emotions", in Dalgleish, T; Power, M (eds.), Handbook of Cognition and Emotion (PDF), Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons

- ^ Lazarus, Richard S.; Lazarus, Bernice N. (23 September 1996). Passion and Reason: Making Sense of Our Emotions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510461-5. Retrieved 23 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Emotional Competency – Recognize these emotions". Emotionalcompetency.com. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ Cowen, Alan S.; Keltner, Dacher (2017). "Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (38): E7900 – E7909. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E7900C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1702247114. PMC 5617253. PMID 28874542.

- ^ "Psychologists Identify Twenty Seven Distinct Categories of Emotion – Psychology". Sci-news.com. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "The Emotions Evoked by Video". Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ Robinson, D. L. (2009). "Brain function, mental experience and personality" (PDF). The Netherlands Journal of Psychology. pp. 152–167.

- ^ a b Reitsema, A.M. (2022). "Emotion dynamics in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic and descriptive review" (PDF). Emotion. 22 (2): 374–396. doi:10.1037/emo0000970. PMID 34843305. S2CID 244748515.

- ^ "HUMAINE Emotion Annotation and Representation Language". Emotion-research.net. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

- ^ Shaver, P.; Schwartz, J.; Kirson, D.; O'connor, C. (1987). "Emotion knowledge: further exploration of a prototype approach". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 52 (6): 1061–86. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1061. PMID 3598857.

- ^ Parrott, W. (2001). Emotions in Social Psychology. Key Readings in Social Psychology. Philadelphia: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-86377-683-0.

- ^ "Basic Emotions—Plutchik". Personalityresearch.org. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Plutchik, R. "The Nature of Emotions". American Scientist. Archived from the original on July 16, 2001. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ "Robert Plutchik's Psychoevolutionary Theory of Basic Emotions" (PDF). Adliterate.com. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- ^ Jonathan Turner (1 June 2000). On the Origins of Human Emotions: A Sociological Inquiry Into the Evolution of Human Affect. Stanford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8047-6436-0.

- ^ Atifa Athar; M. Saleem Khan; Khalil Ahmed; Aiesha Ahmed; Nida Anwar (June 2011). "A Fuzzy Inference System for Synergy Estimation of Simultaneous Emotion Dynamics in Agents". International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 2 (6).

- ^ a b TenHouten, Warren D. (1 December 2016). Alienation and Affect. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-67853-3. Retrieved 25 June 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chorianopoulos, Konstantinos; Divitini, Monica; Hauge, Jannicke Baalsrud; Jaccheri, Letizia; Malaka, Rainer (24 September 2015). Entertainment Computing - ICEC 2015: 14th International Conference, ICEC 2015, Trondheim, Norway, September 29 - October 2, 2015, Proceedings. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-24589-8. Retrieved 25 June 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Plutchik, Robert (25 June 1991). The Emotions. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-8286-9. Retrieved 25 June 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy, John (4 December 2012). Consumer Behaviour: Perspectives, Findings and Explanations. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 978-1-137-00378-2. Retrieved 25 June 2019 – via Google Books.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Plutchik, Robert (31 December 1991). The Emotions. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-8286-9. Retrieved 31 December 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Izard, Carroll Ellis (31 December 1971). The face of emotion. Appleton-Century-Crofts. ISBN 978-0-390-47831-3. Retrieved 31 December 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Nature of Emotions" (PDF). Emotionalcompetency.com. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ^ Plutchik, Robert (16 September 1991). The Emotions. University Press of America. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8191-8286-9. Retrieved 16 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ TenHouten, Warren D. (23 June 2014). Emotion and Reason: Mind, Brain, and the Social Domains of Work and Love. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-58061-4. Retrieved 10 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ TenHouten, Warren D. (22 November 2006). A General Theory of Emotions and Social Life. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-22907-9. Retrieved 10 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ TenHouten, Warren D. (22 November 2006). A General Theory of Emotions and Social Life. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-22908-6. Retrieved 10 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Kort, B.; Reilly, R.; Picard, R.W. (2001). "An affective model of interplay between emotions and learning: Reengineering educational pedagogy-building a learning companion". Proceedings IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies. pp. 43–46. doi:10.1109/ICALT.2001.943850. ISBN 0-7695-1013-2. S2CID 9573470 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Tiffany Watt Smith. "The Book of Human Emotions: An Encyclopedia of Feeling from Anger to Wanderlust" (PDF). Anarchiveforemotions.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 2017-05-28.

- ^ "Invisibilia: A Man Finds An Explosive Emotion Locked In A Word". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-12-29.

- ^ "Happily disgusted? Scientists map facial expressions for 21 emotions". The Guardian. 31 March 2014.

- ^ Jacque Wilson (2014-04-04). "Happily disgusted? 15 new emotions ID'd". KSL.com. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

.jpg/250px-Sixteen_faces_expressing_the_human_passions._Wellcome_L0068375_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg/1616px-Sixteen_faces_expressing_the_human_passions._Wellcome_L0068375_(cropped).jpg)