Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Estrous cycle

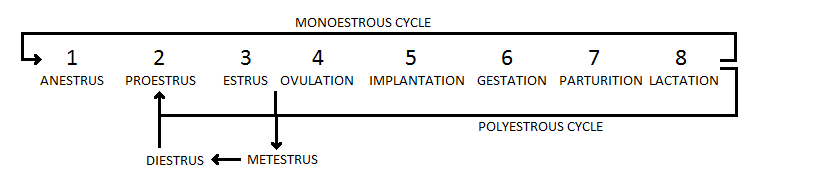

View on WikipediaThe estrous cycle (from Latin oestrus 'frenzy', originally from Ancient Greek οἶστρος (oîstros) 'gadfly') is a set of recurring physiological changes induced by reproductive hormones in females of mammalian subclass Theria.[1] Estrous cycles start after sexual maturity in females and are interrupted by anestrous phases, otherwise known as "rest" phases, or by pregnancies. Typically, estrous cycles repeat until death. These cycles are widely variable in duration and frequency depending on the species.[2] Some animals may display bloody vaginal discharge, often mistaken for menstruation.[3] Many mammals used in commercial agriculture, such as cattle and sheep, may have their estrous cycles artificially controlled with hormonal medications for optimum productivity.[4][5] The male equivalent, seen primarily in ruminants, is called rut.[2]

Differences from the menstrual cycle

[edit]Mammals share the same reproductive system, including the regulatory hypothalamic system that produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone in pulses, the pituitary gland that secretes follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, and the ovary itself that releases sex hormones, including estrogens and progesterone.

However, animals that have estrous cycles resorb the endometrium if conception does not occur during that cycle. Mammals that have menstrual cycles shed the endometrium through menstruation instead.

Humans, elephant shrews, and a few other species have menstrual cycles rather than estrous cycles. Humans, unlike most other species, have concealed ovulation, a lack of obvious external signs to signal estral receptivity at ovulation (i.e., the ability to become pregnant). Some species of animals with estrous cycles have unmistakable outward displays of receptivity, ranging from engorged and colorful genitals to behavioral changes like mating calls.

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]Estrus is derived via Latin oestrus ('frenzy', 'gadfly'), from Greek οἶστρος oîstros (literally 'gadfly', more figuratively 'frenzy', 'madness', among other meanings like 'breeze'). Specifically, this refers to the gadfly in Ancient Greek mythology that Hera sent to torment Io, who had been won in her heifer form by Zeus.[citation needed] Euripides used oestrus to indicate 'frenzy', and to describe madness. Homer used the word to describe panic.[6] Plato also used it to refer to an irrational drive[7] and to describe the soul "driven and drawn by the gadfly of desire".[8] Somewhat more closely aligned to current meaning and usage of estrus, Herodotus (Histories, ch. 93.1) uses oîstros to describe the desire of fish to spawn.[9]

The earliest use in English was with a meaning of 'frenzied passion'. In 1900, it was first used to describe 'rut in animals; heat'.[10][11]

In British English, the spelling is oestrus or (rarely) œstrus. In all English spellings, the noun ends in -us and the adjective in -ous. Thus in Modern International English, a mammal may be described as "in estrus" when it is in that particular part of the estrous-cycle.

Four phases

[edit]A four-phase terminology is used in reference to animals with estrous cycles.

Proestrus

[edit]One or several follicles of the ovary start to grow. Their number is species-specific. Typically, this phase can last as little as one day or as long as three weeks, depending on the species. Under the influence of estrogen, the lining of the uterus (endometrium) starts to develop. Some animals may experience vaginal secretions that could be bloody. The female is not yet sexually receptive; the old corpus luteum degenerates; the uterus and the vagina distend and fill with fluid, become contractile and secrete a sanguinous fluid; the vaginal epithelium proliferates and the vaginal cytology shows a large number of non-cornified nucleated epithelial cells. Variant terms for proestrus include pro-oestrus, proestrum, and pro-oestrum.

Estrus

[edit]Estrus or oestrus refers to the phase when the female is sexually receptive ("in heat" in American English, or "on heat" in British English). Under regulation by gonadotropic hormones, ovarian follicles mature and estrogen secretions exert their biggest influence. The female then exhibits sexually receptive behavior, a situation that may be signaled by visible physiologic changes. Estrus is commonly seen in the mammalian species, including some primates.

In some species, the vulva becomes swollen and reddened.[12] Ovulation may occur spontaneously in others. Especially among quadrupeds, a signal trait of estrus is the lordosis reflex, in which the animal spontaneously elevates her hindquarters.

Controlled internal drug release devices are used in livestock for the synchronization of estrus.

Metestrus or diestrus

[edit]This phase is characterized by the activity of the corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. The signs of estrogen stimulation subside and the corpus luteum starts to form. The uterine lining begins to appear. In the absence of pregnancy, the diestrus phase (also termed pseudopregnancy) terminates with the regression of the corpus luteum. The lining in the uterus is not shed, but is reorganized for the next cycle. Other spellings include metoestrus, metestrum, metoestrum, dioestrus, diestrum, and dioestrum.

Anestrus

[edit]Anestrus refers to the phase when the sexual cycle rests. This is typically a seasonal event and controlled by light exposure through the pineal gland that releases melatonin. Melatonin may repress stimulation of reproduction in long-day breeders and stimulate reproduction in short-day breeders. Melatonin is thought to act by regulating the hypothalamic pulse activity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Anestrus is induced by time of year, pregnancy, lactation, significant illness, chronic energy deficit, and possibly age. Chronic exposure to anabolic steroids may also induce a persistent anestrus due to negative feedback on the hypothalamus/pituitary/gonadal axis. Other spellings include anoestrus, anestrum, and anoestrum.

After completion (or abortion) of a pregnancy, some species have postpartum estrus, which is ovulation and corpus luteum production that occurs immediately following the birth of the young.[13] For example, the mouse has a fertile postpartum estrus that occurs 14 to 24 hours following parturition.

Cycle-variability

[edit]Estrous cycle variability differs among species, but cycles are typically more frequent in smaller animals. Even within species significant variability can be observed, thus cats may undergo an estrous cycle of 3 to 7 weeks.[14] Domestication can affect estrous cycles due to changes in the environment. For most species, vaginal smear cytology may be used in order to identify estrous cycle phases and durations.[15]

Frequency

[edit]Some species, such as cats, cows and domestic pigs, are polyestrous, meaning that they can go into heat several times per year. Seasonally polyestrous animals or seasonal breeders have more than one estrous cycle during a specific time of the year and can be divided into short-day and long-day breeders:

- Short-day breeders, such as sheep, goats, deer and elk are sexually active in fall or winter.

- Long-day breeders, such as horses, hamsters and ferrets are sexually active in spring and summer.

Species that go into heat twice per year are diestrous. Canines are diestrous.[citation needed]

Monestrous species, such as canids[16] and bears, have only one breeding season per year, typically in spring to allow growth of the offspring during the warm season to aid survival during the next winter.

A few mammalian species, such as rabbits, do not have an estrous cycle, instead being induced to ovulate by the act of mating and are able to conceive at almost any arbitrary moment.

Generally speaking, the timing of estrus is coordinated with seasonal availability of food and other circumstances such as migration, predation etc., the goal being to maximize the offspring's chances of survival. Some species are able to modify their estral timing in response to external conditions.

Specific species

[edit]Cats

[edit]The female cat in heat has an estrus of 14 to 21 days and is generally characterized as an induced ovulator, since coitus induces ovulation. However, various incidents of spontaneous ovulation have been documented in the domestic cat and various non-domestic species.[17] Without ovulation, she may enter interestrus, which is the combined stages of diestrus and anestrus, before reentering estrus. With the induction of ovulation, the female becomes pregnant or undergoes a non-pregnant luteal phase, also known as pseudopregnancy. Cats are polyestrous but experience a seasonal anestrus in autumn and late winter.[18]

Dogs

[edit]A female dog is usually diestrous (goes into heat typically twice per year), although some breeds typically have one or three cycles per year. The proestrus is relatively long at 5 to 9 days, while the estrus may last 4 to 13 days, with a diestrus of 60 days followed by about 90 to 150 days of anestrus. Female dogs bleed during estrus, which usually lasts from 7–13 days, depending on the size and maturity of the dog. Ovulation occurs 24–48 hours after the luteinizing hormone peak, which occurs around the fourth day of estrus; therefore, this is the best time to begin breeding. Proestrus bleeding in dogs is common and is believed to be caused by diapedesis of red blood cells from the blood vessels due to the increase of the estradiol-17β hormone.[19]

Horses

[edit]A mare may be in heat for 4 to 10 days, followed by approximately 14 days in diestrus. Thus, a cycle may be short, totaling approximately 3 weeks.[20] Horses mate in spring and summer; autumn is a transition time, and anestrus occurs during winter.

A feature of the fertility cycle of horses and other large herd animals is that it is usually affected by the seasons. The number of hours daily that light enters the eye of the animal affects the brain, which governs the release of certain precursors and hormones. When daylight hours are few, these animals "shut down", become anestrous, and do not become fertile. As the days grow longer, the longer periods of daylight cause the hormones that activate the breeding cycle to be released. As it happens, this benefits these animals in that, given a gestation period of about eleven months, it prevents them from having young when the cold of winter would make their survival risky.

Rats

[edit]Rats are polyestrous animals that typically have rapid cycle lengths of 4 to 5 days.[21] Although they ovulate spontaneously, they do not develop a fully functioning corpus luteum unless they receive coital stimulation. Fertile mating leads to pregnancy in this way, but infertile mating leads to a state of pseudopregnancy lasting about 10 days. Mice and hamsters have similar behavior.[22] The events of the cycle are strongly influenced by lighting periodicity.[10]

A set of follicles starts to develop near the end of proestrus and grows at a nearly constant rate until the beginning of the subsequent estrus when the growth rates accelerate eightfold. Ovulation occurs about 109 hours after the start of follicle growth.

Estrogen peaks at about 11 am on the day of proestrus. Between then and midnight there is a surge in progesterone, luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, and ovulation occurs at about 4 am on the next estrus day. The following day, metestrus, is called early diestrus or diestrus I. During this day, the corpora lutea grow to a maximal volume, achieved within 24 hours of ovulation. They remain at that size for three days, halve in size before the metestrus of the next cycle and then shrink abruptly before estrus of the cycle after that. Thus the ovaries of cycling rats contain three different sets of corpora lutea at different phases of development.[23]

Bison

[edit]Buffalo have an estrous cycle of about 22 to 24 days. Buffalo are known for difficult estrus detection. This is one major reason for being less productive than cattle. During four phases of its estrous cycle, mean weight of corpus luteum has been found to be 1.23±0.22g (metestrus), 3.15±0.10g (early diestrus), 2.25±0.32g (late diestrus), and 1.89±0.31g (proestrus/estrus), respectively. The plasma progesterone concentration was 1.68±0.37, 4.29±0.22, 3.89±0.33, and 0.34±0.14 ng/ml while mean vascular density (mean number of vessels/10 microscopic fields at 400x) in corpus luteum was 6.33±0.99, 18.00±0.86, 11.50±0.76, and 2.83±0.60 during the metestrus, early diestrus, late diestrus and proestrus/estrus, respectively.[24]

Cattle

[edit]Female cattle, also referred to as "heifers" in agriculture, will gradually enter standing estrus, or "standing heat," starting at puberty between 9 and 15 months of age. The cow estrous cycle typically lasts 21 days.[5] Standing estrus is a visual cue which signifies sexual receptivity for mounting by male cattle. This behavior lasts anywhere between 8 and 30 hours at a time.[25] Other behaviors of the female during standing estrus may change, including, but not limited to: nervousness, swollen vulva, or attempting to mount other animals.[25] While visual and behavioral cues are helpful to the male cattle, estrous stages cannot be determined by the human eye. Rather, the stage can be estimated from the appearance of the corpora lutea or follicle composition.[26][27]

Estrous control

[edit]Due to the widespread use of bovine animals in agriculture, cattle estrous cycles have been widely studied, and manipulated, in an effort to maximize profitability through reproductive management.[25] Much estrous control in cattle is for the purpose of synchronization, a practice or set of practices most often used by cattle farmers to control the timing and duration of estrus in large herds.[4]

There is variation between the available methods of cattle estrous synchronization. Treatment depends on herd size, specific goals for control, and budget.[4] Some of the FDA-approved drugs and devices used to mimic natural hormones of the estrous cycle include, but are not limited to, the following classes:

- Gonadorelin: There are currently five available gonadorelin products that are FDA-Approved.[28] Usually, gonadorelin is used in conjunction with another estrous control drug (typically, prostaglandin).[28][29] This drug is used to mimic gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) and may also be used to treat ovarian cysts.[5]

- Prostaglandin: Mimics the prostaglandin F2-alpha hormone released when no pregnancy has occurred and regresses the corpus luteum.[5] This drug is used to achieve more consistent results in artificial insemination.[29]

- Progestin: Used to suppress estrus and/or block ovulation.[5] Most commonly, it is administered via an intravaginal insert comparable to an IUD, which used in controlling menstrual periods.[30] It is also available as a medicated feed, but this method is not yet approved for cattle crop synchronization.[5]

There is variation between the available methods of cattle estrous synchronization. Treatment depends on herd size, specific goals for control, and budget.[4]

Bovine estrous cycles may also be impacted by other bodily functions such as oxytocin levels.[31] Additionally, heat stress has been linked to impairment of follicular development, especially impactful to the first-wave dominant follicle.[32] Future synchronization programs are planning to focus on the impact of heat stress on fertilization and embryonic death rates after artificial insemination.[33]

Additionally, work has been done regarding other mammalian females, such as in dogs, for estrous control; However, there are yet to be any approved medications outside of those commercially available.[34]

Others

[edit]Estrus frequencies of some other notable mammals:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hill, M. A. (2021, April 6) Embryology Estrous Cycle. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Estrous_Cycle

- ^ a b Bronson, F. H., 1989. Mammalian Reproductive Biology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, USA.

- ^ Llera, Ryan; Yuill, Cheryl (2021). "Estrous Cycles in Dogs". VCA Hospitals. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Synchronizing Estrus in Cattle - How does estrus synchronization work?". Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service. Retrieved 2021-03-22.

- ^ a b c d e f Medicine, Center for Veterinary (2021-03-05). "The Cattle Estrous Cycle and FDA-Approved Animal Drugs to Control and Synchronize Estrus—A Resource for Producers". FDA.[dead link]

- ^ Panic of the suitors in Homer, Odyssey, book 22

- ^ Plato, Laws, 854b

- ^ Plato, The Republic

- ^ Herodotus, Histories, ch. 93.1

- ^ a b Freeman, Marc E. (1994). "The Neuroendocrine control of the ovarian cycle of the rat". In Knobil, E.; Neill, J. D. (eds.). The Physiology of Reproduction. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Raven Press.

- ^ Heape, W. (1900). "The 'sexual season' of mammals and the relation of the 'pro-oestrum' to menstruation'". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 44: 1:70.

- ^ Weir, Malcolm. "Estrus and Mating in Dogs". VCA Animal Hospital.

- ^ medilexicon.com > postpartum estrus Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine citing: Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Copyright 2006

- ^ Griffin, Brenda (December 2001). "Prolific Cats: The Oestrous Cycle" (PDF). Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian. 23 (12): 1049–1056.

- ^ Marcondes, F. K.; Bianchi, F. J.; Tanno, A. P. (November 2002). "Determination of the oestrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations". Brazilian Journal of Biology. 62 (4A): 609–614. doi:10.1590/S1519-69842002000400008. ISSN 1519-6984. PMID 12659010.

- ^ Valdespino, C.; Asa, C.S. & Bauman, J.E. (2002). "Estrous cycles, copulation and pregnancy in the fennec fox (Vulpes zerda)" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 83 (1): 99–109. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2002)083<0099:ECCAPI>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 51812228.

- ^ Pelican et al., 2006

- ^ Spindler and Wildt, 1999

- ^ Walter, I.; Galabova, G.; Dimov, D.; Helmreich, M. (February 2011). "The morphological basis of proestrus endometrial bleeding in canines". Theriogenology. 75 (3): 411–420. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.04.022. PMID 21112080.

- ^ Aurich, Christine (2011-04-01). "Reproductive cycles of horses". Animal Reproduction Science. Special Issue: Reproductive Cycles of Animals. 124 (3): 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2011.02.005. ISSN 0378-4320. PMID 21377299.

- ^ Hill, M.A. (2021, March 11) Embryology Estrous Cycle. Retrieved from https://embryology.med.unsw.edu.au/embryology/index.php/Estrous_Cycle

- ^ McCracken, J. A.; Custer, E. E.; Lamsa, J. C. (1999). "Luteolysis: A neuroendocrine-mediated event". Physiological Reviews. 79 (2): 263–323. doi:10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.263. PMID 10221982.

- ^ Yoshinaga, K. (1973). "Gonadotrophin-induced hormone secretion and structural changes in the ovary during the nonpregnant reproductive cycle". Handbook of Physiology. Vol. Endocrinology II, Part 1.

- ^ Qureshi, A. S.; Hussain, M.; Rehan, S.; Akbar, Z.; Rehman, N. U. (2015). "Morphometric and angiogenic changes in the corpus luteum of nili-ravi buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) during estrous cycle". Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 52 (3): 795–800.

- ^ a b c Perry, George (2004). Salverson, Robin (ed.). "The Bovine Estrous Cycle" (PDF). SDSU Extension.

- ^ Ireland, James J.; Murphee, R.L.; Coulson, P.B. (1980). "Accuracy of Predicting Stages of Bovine Estrous Cycle by Gross Appearance of the Corpus Luteum". Journal of Dairy Science. 63 (1): 155–160. doi:10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(80)82901-8. ISSN 0022-0302. PMID 7372895.

- ^ Ginther, O. J.; Kastelic, J. P.; Knopf, L. (1989-09-01). "Composition and characteristics of follicular waves during the bovine estrous cycle". Animal Reproduction Science. 20 (3): 187–200. doi:10.1016/0378-4320(89)90084-5. ISSN 0378-4320.

- ^ a b Medicine, Center for Veterinary (2018-11-03). "Fertagyl® (gonadorelin acetate) - Veterinarians". FDA. Archived from the original on September 30, 2019.

- ^ a b "LUTALYSE® Injection (dinoprost injection)". www.zoetisus.com. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- ^ "Hormonal Control of Estrus in Cattle - Management and Nutrition". Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 2021-03-22.

- ^ Armstrong, D.T.; Hansel, William (1959). "Alteration of the Bovine Estrous Cycle with Oxytocin". Journal of Dairy Science. 42 (3): 533–542. doi:10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(59)90607-1. ISSN 0022-0302.

- ^ Wolfenson, D.; Thatcher, W. W.; Badinga, L.; Savi0, J. D.; Meidan, R.; Lew, B. J.; Braw-tal, R.; Berman, A. (1995-05-01). "Effect of Heat Stress on Follicular Development during the Estrous Cycle in Lactating Dairy Cattle1". Biology of Reproduction. 52 (5): 1106–1113. doi:10.1095/biolreprod52.5.1106. ISSN 0006-3363. PMID 7626710.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Santos, J. E. P; Thatcher, W. W; Chebel, R. C; Cerri, R. L. A; Galvão, K. N (2004-07-01). "The effect of embryonic death rates in cattle on the efficacy of estrus synchronization programs". Animal Reproduction Science. Research and Practice III. 15th International Congress on Animal Reproduction. 82–83: 513–535. doi:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.04.015. ISSN 0378-4320. PMID 15271477.

- ^ Kutzler MA. Estrous Cycle Manipulation in Dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2018 Jul;48(4):581-594. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2018.02.006. Epub 2018 Apr 27. PMID 29709316.

Further reading

[edit]- Spindler, R. E.; Wildt, D. E. (1999). "Circannual variations in intraovarian oocyte but not epididymal sperm quality in the domestic cat". Biology of Reproduction. 61 (1): 188–194. doi:10.1095/biolreprod61.1.188. PMID 10377048.

- Pelican, K.; Wildt, D.; Pukazhenthi, B.; Howard, J. G. (2006). "Ovarian control for assisted reproduction in the domestic cat and wild felids". Theriogenology. 66 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.03.013. PMID 16630653.

External links

[edit]- Systematic overview

- Etymology

- Cat estrous cycle

- Horse estrous cycle

- Dogs in Heat - FAQ

- Skloot, Rebecca (December 9, 2007). "Lap-dance Science". The New York Times Magazine.

Estrous cycle

View on GrokipediaIntroduction and Fundamentals

Definition and Overview

The estrous cycle refers to the recurring physiological changes in the reproductive tract of female non-primate mammals, induced by reproductive hormones, that lead to periods of estrus (heat) and ovulation.[4] This cycle represents the primary reproductive process in these species, distinguishing it from the menstrual cycle observed in higher primates.[5] The core purpose of the estrous cycle is to synchronize female behavioral receptivity to mating with ovarian follicle development and the preparation of the reproductive tract for potential pregnancy.[1] These coordinated changes ensure that ovulation occurs during a discrete window of fertility, optimizing reproductive success by aligning physiological readiness with opportunities for conception.[6] The duration of the estrous cycle varies widely among non-primate mammalian species, typically from 4-5 days in rodents to about 21 days in ruminants and horses, contrasting with the more continuous estrus-like receptivity in primates.[5] The cycle involves key anatomical structures, including the ovaries for follicle maturation and ovulation, the uterus for endometrial changes, and the hypothalamus-pituitary axis for hormonal orchestration.[4] It comprises distinct phases—proestrus, estrus, metestrus, and diestrus—that drive these reproductive events, with an optional anestrus period of reproductive quiescence.[7]Etymology and Nomenclature

The term "estrous cycle" derives its first component from the noun "estrus," which originates from the Latin oestrus meaning "frenzy" or "gadfly," itself borrowed from the Ancient Greek oîstros (οἶστρος), denoting a gadfly, sting, breeze, or mad impulse that drives animals into a frenzied state, metaphorically applied to the intense sexual behavior observed in females during heat.[8] The second component, "cycle," comes from the Late Latin cyclus and Old French cicle, ultimately from the Greek kyklos (κύκλος) meaning "circle" or "wheel," signifying a recurring series of events or operations.[9] The nomenclature was formalized in the early 20th century by British zoologist Walter Heape, who in 1900 introduced the term "estrous cycle" (spelled "oestrous" in British English) to describe the reproductive periodicity in non-primate mammals, explicitly distinguishing it from the human menstrual cycle based on observable behavioral and physiological patterns.[10] Heape's work emphasized the cycle's role in the "sexual season" of mammals, coining phase-specific terms such as proestrus (the preparatory period leading into heat), estrus (the peak of sexual receptivity), metestrus (the immediate post-heat subsidence), diestrus (a brief rest within the breeding season), and anestrus (the extended non-breeding rest period).[11] In modern usage, "estrous" is the standard American English spelling, while "oestrous" persists in British English, reflecting orthographic conventions for words derived from Latin and Greek roots.[12] This terminology contrasts with the "menstrual cycle," which Heape and subsequent researchers reserved for primates exhibiting overt bleeding, whereas estrous cycles in other mammals are characterized by behavioral "heat" without such menstruation.[11] Colloquially, the estrous cycle is often referred to as "heat," "rut," or "breeding season" in veterinary and agricultural contexts, terms that capture the female's limited window of fertility and mating willingness.[12]Comparison to Menstrual Cycle

Key Differences

The estrous cycle, characteristic of most non-primate mammals, differs fundamentally from the menstrual cycle observed in humans and some other primates in the handling of uterine tissue. In the estrous cycle, the endometrium undergoes resorption or reorganization if pregnancy does not occur, without significant shedding or visible bleeding, conserving energy and minimizing physiological costs.[13] In contrast, the menstrual cycle involves the sloughing off of the endometrial lining, resulting in menstrual bleeding, which is a response to progesterone withdrawal in the absence of implantation.[2] This absence of overt discharge in estrous species reflects an adaptation to maintain reproductive efficiency without the need for extensive tissue regeneration each cycle.[14] Cycle continuity also sets the estrous and menstrual cycles apart. Estrous cycles can be polyestrous (either continuous year-round or multiple within defined breeding seasons), seasonally polyestrous, or monoestrous annually, with many aligning with environmental cues like photoperiod to concentrate reproductive efforts.[15] For instance, many mammals exhibit multiple estrous cycles during a favorable period, followed by anestrus, whereas the menstrual cycle operates continuously year-round, independent of seasons, allowing for more frequent reproductive opportunities.[13] This seasonal patterning in estrous cycles optimizes resource allocation for offspring survival in variable environments.[16] Behaviorally, the estrous cycle features pronounced sexual receptivity confined to the brief estrus phase, often marked by overt signs like vocalizations or postures that signal readiness for mating, tightly coupling behavior to ovulation.[2] The menstrual cycle decouples these elements, with females potentially receptive throughout the cycle, not solely during fertile periods, which supports social bonding in primate groups.[13] Evolutionarily, the estrous cycle represents an adaptation for species with discrete breeding seasons, synchronizing reproduction with optimal conditions for offspring viability, such as abundant food or milder weather, thereby enhancing survival rates in non-primate mammals.[14] Menstrual cycles, conversely, evolved in lineages favoring continuous cycling, possibly to facilitate embryo selection and protection against suboptimal pregnancies through spontaneous decidualization.[17] If conception fails, outcomes diverge markedly: the estrous cycle may result in quiet ovulation or pseudopregnancy, with the corpus luteum regressing without endometrial disruption, leading seamlessly to the next cycle or anestrus.[13] In the menstrual cycle, non-pregnancy triggers menstruation, clearing the uterus for a new proliferative phase.Physiological Similarities

The estrous and menstrual cycles share fundamental physiological mechanisms that underscore their evolutionary conservation across mammals, enabling reproductive success through coordinated ovarian and uterine changes. Both cycles feature an ovarian component involving the sequential development of ovarian follicles, ovulation of a mature oocyte, and subsequent formation of the corpus luteum, which supports potential pregnancy by secreting progesterone. In estrous cycles of species like rodents and dogs, follicles progress from primordial to antral stages under gonadotropin influence, culminating in ovulation triggered by a luteinizing hormone (LH) surge, followed by luteinization of granulosa and theca cells into the corpus luteum; similarly, in the menstrual cycle of primates including humans, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) drives follicular maturation, with ovulation occurring mid-cycle and the corpus luteum forming post-ovulation to maintain the endometrium. These processes ensure the release of gametes at optimal times for fertilization.[18][19] Hormonal regulation in both cycles is governed by the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, which integrates positive and negative feedback loops to orchestrate cyclicity. The hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in pulsatile fashion to stimulate pituitary secretion of FSH and LH, which in turn promote ovarian steroidogenesis; rising estradiol levels exert positive feedback to induce the pre-ovulatory LH surge for ovulation, while negative feedback from progesterone and inhibin suppresses gonadotropins during the luteal phase to prevent premature follicle recruitment. This axis operates comparably in estrous mammals, such as rats and sheep, where feedback dynamics maintain short cycles, and in menstrual cycles, sustaining longer phases with similar steroid-mediated control.[19] Uterine preparation for implantation exhibits parallel endometrial responses driven by ovarian hormones in both cycles. Estrogen stimulates endometrial proliferation during the follicular/proestrus phase, thickening the lining through glandular and stromal cell growth to create a receptive environment; progesterone from the corpus luteum then induces secretory changes for nutrient support if fertilization occurs. In estrous cycles, such as in dogs, this proliferation peaks pre-ovulation without overt bleeding, while in menstrual cycles, it prepares the endometrium for potential decidualization, highlighting conserved estrogen-progesterone synergy for implantation.[1][19] The duration of the fertile window aligns closely relative to overall cycle length in both systems, with ovulation marking the peak fertility period typically 12-24 hours after the LH surge, and viable spermatozoa surviving up to several days prior. In a standard 28-day menstrual cycle, ovulation occurs around day 14, yielding a 5-6 day fertile window; analogously, in the 4-5 day rodent estrous cycle, ovulation follows proestrus, confining fertility to estrus with similar relative timing for conception. This synchronization optimizes gamete encounter across species.[20][21] At the molecular level, core genes encoding receptors for gonadotropins, such as FSH receptor (FSHR) and LH/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHCGR), demonstrate high conservation across mammals, facilitating uniform signaling in reproductive cycles. FSHR, a G-protein-coupled receptor, mediates FSH-driven folliculogenesis with conserved transmembrane domains and key residues (e.g., Asp224) essential for activation in both estrous and menstrual contexts; LHCGR similarly supports LH-induced ovulation and luteal function through shared structural motifs, ensuring robust hormone responsiveness from rodents to primates.[22]Phases of the Cycle

Proestrus

The proestrus phase represents the preparatory stage of the estrous cycle in female mammals, during which the reproductive system undergoes changes to support follicle maturation and impending ovulation. This phase is marked by the regression of the corpus luteum from the previous cycle, leading to declining progesterone levels and the initiation of follicular development in the ovaries. As a result, circulating estrogen concentrations begin to rise, setting the stage for subsequent phases.[7] The duration of proestrus varies significantly across species, typically spanning 2-4 days in many domestic mammals, though shorter in rodents (e.g., 12-24 hours in rats and mice) and longer in others (e.g., 6-11 days in dogs). In cattle, it lasts 1-3 days, characterized by follicular waves where multiple follicles grow but only one dominant follicle emerges. Physiological changes include accelerated growth of ovarian follicles stimulated by rising follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary, with granulosa cells in the developing follicles increasingly producing estradiol. This estrogen surge promotes endometrial proliferation in the uterus, thickening the lining through cellular mitosis to prepare for potential embryo implantation, while also influencing cervical mucus production to become more watery and fertile.[23][24][7][25] Behaviorally, females during proestrus show limited sexual receptivity to males, distinguishing this phase from the receptive estrus that follows, though they may display increased playfulness or attraction in some species like dogs. Common physical signs include vulvar swelling due to estrogen-induced vascularization and clear or slightly bloody vaginal discharge, which aids in lubrication and signals approaching fertility; in rodents, the vagina appears swollen and moist with nucleated epithelial cells observable in smears. These changes reflect the mounting estrogen influence on accessory reproductive structures.[24][7] Hormonally, proestrus is triggered by pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which stimulates the pituitary gland to release escalating levels of FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH). The rising estrogen provides positive feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary, amplifying GnRH and gonadotropin secretion. This phase endpoints with a critical preovulatory LH surge, typically occurring toward the close of proestrus, which induces final oocyte maturation, ovulation within 24-36 hours, and the shift to estrus.[3][25][7]Estrus

Estrus, also known as "heat," represents the fertile phase of the estrous cycle in female mammals, marked by peak sexual receptivity, ovulation, and physiological adaptations that facilitate mating and conception.[19] This phase follows the preparatory follicular development in proestrus and is the period when the female is most likely to accept a male for copulation, optimizing the chances of successful fertilization.[7] In general, estrus is the shortest phase of the cycle, typically lasting 1-2 days across many mammalian species, though durations vary; for instance, it may extend to 2-3 days in swine or be as brief as 12-18 hours in cattle.[19][26] Physiologically, estrus is characterized by the culmination of follicular maturation, with ovulation occurring as the dominant event, triggered by a preovulatory surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) that typically happens toward the end of proestrus but results in egg release during early estrus.[7] The reproductive tract undergoes key changes to support sperm transport and survival: cervical mucus becomes abundant, watery, and sperm-friendly with a characteristic ferning pattern that enhances motility, while uterine contractions increase to propel sperm toward the oviducts.[19] These adaptations, driven by elevated estrogen levels reaching their maximum, create an optimal environment for fertilization shortly after insemination.[26] Behaviorally, females exhibit pronounced signs of receptivity during estrus, including attraction to males, increased vocalizations, and specific postures such as lordosis in rodents or "standing heat" in many ungulates like cattle and swine, where the female rigidly stands to allow mounting.[19] These behaviors are estrogen-mediated and signal peak fertility, often accompanied by restlessness, frequent mounting of other females, and vulvar swelling or discharge.[26] Hormonally, estrus follows the LH surge, with estrogen concentrations at their zenith to sustain receptivity, while progesterone levels begin to rise post-ovulation as the corpus luteum starts forming, marking the transition to subsequent phases.[7] The fertility window during estrus is narrow but critical, with optimal insemination timing aligned to the period of receptivity, as the released ova remain viable for approximately 12-24 hours in most mammals.[19] This brief viability underscores the importance of synchronized mating, with sperm survival in the female tract potentially extending up to 48 hours in some species to overlap with ovulation.[7]Metestrus

Metestrus represents the immediate post-ovulatory phase of the estrous cycle in mammals, typically lasting 2 to 4 days, as observed in species such as cattle and sheep.[27][28] This brief interval follows the cessation of estrus and is characterized by the onset of luteal development following ovulation, which occurs approximately 10 to 15 hours after the end of behavioral receptivity in bovines.[27] Physiologically, the corpus hemorrhagicum—a blood clot-filled structure—forms within the ovarian follicle's rupture site, serving as the precursor to the corpus luteum through luteinization of granulosa and theca cells.[27][29] This early corpus luteum initiates low-level progesterone secretion, which gradually rises but remains insufficient for full luteal support initially, while circulating estrogen concentrations decline sharply from estrus peaks.[27][30] Behaviorally, sexual receptivity diminishes quickly, with females exhibiting reduced attraction to males and no further mating attempts, signaling the end of the fertile window.[27][31] In the uterus, rising progesterone prompts initial endometrial changes, including glandular proliferation and vascular remodeling, to prepare for embryo implantation should fertilization occur.[32][33] However, without an embryo, these preparatory alterations remain transient and reversible, allowing the reproductive tract to reset for subsequent cycles.[34] If conception fails, early signs of pseudopregnancy—such as mild mammary gland development—may emerge in certain species like dogs, driven by sustained progesterone influence.[35] Overall, metestrus functions as a critical bridge from the ovulatory events of estrus to the sustained luteal dominance of diestrus, stabilizing the post-ovulatory environment while maintaining reproductive plasticity.[27][36]Diestrus

Diestrus represents the luteal phase of the estrous cycle in mammals, characterized by the dominance of progesterone secreted by the mature corpus luteum, which supports potential implantation and early pregnancy or regresses if fertilization does not occur.[37] This phase typically lasts 10-14 days in many species, making it the longest segment of the cycle, though durations vary; for instance, it spans approximately 12 days in cattle and 14-15 days in mares.[27][38] Following the brief metestrus transition, the corpus luteum fully matures during diestrus, inhibiting the development of new ovarian follicles through negative feedback on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.[37] Physiologically, the elevated progesterone prepares the reproductive tract for gestation, thickening the endometrium and promoting glandular secretions in species like cattle, while suppressing further ovulation.[27] If pregnancy occurs, progesterone sustains the corpus luteum and initiates mammary gland development for lactation, as seen in livestock such as pigs and cows.[39] Hormonally, progesterone levels rise to and maintain above 5 ng/mL—reaching 30-40 ng/mL in pigs—suppressing gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) release, thereby preventing premature follicular growth.[37][40] Behaviorally, females exhibit no sexual receptivity during diestrus, often displaying increased aggression or, if pregnant, early maternal tendencies, as progesterone overrides estrogen-driven behaviors observed in prior phases.[38] The phase concludes with luteolysis, the regression of the corpus luteum triggered by uterine-derived prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) in non-pregnant animals, leading to a sharp decline in progesterone and the onset of proestrus; this process is well-documented in ruminants like cattle, where PGF2α pulses initiate the next cycle.[27][39]Anestrus

Anestrus represents the phase of reproductive dormancy in the estrous cycle of many mammals, marked by a complete cessation of follicular development, ovulation, and behavioral estrus, with females exhibiting indifference or resistance to mating advances.[41] During this period, the reproductive tract remains quiescent, including small, inactive ovaries and a uterus with minimal endometrial activity.[42] This phase contrasts with the active cycling periods of proestrus, estrus, metestrus, and diestrus by imposing a prolonged interval of infertility.[43] The duration of anestrus varies widely across species and environmental contexts, typically ranging from several weeks to months, and is often pronounced in seasonal breeders from temperate regions.[42] For instance, in long-day breeders such as horses and donkeys, anestrus may last 3–5 months during autumn and winter, while in short-day breeders like sheep, it occurs over summer, spanning 2–3 months.[44] Postpartum anestrus can extend longer, such as 12–24 months in elephants under natural conditions, though it shortens with reduced stress.[41] Physiologically, anestrus features suppressed secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, resulting in low circulating levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).[42] This leads to ovarian inactivity, with follicles undergoing atresia rather than maturation, and correspondingly low concentrations of estradiol and progesterone.[44] Uterine involution occurs, minimizing metabolic demands on the reproductive system.[43] Key causes of anestrus include environmental cues that inhibit hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis activity, such as shortened photoperiods in winter for long-day breeders, which elevate melatonin and dampen GnRH pulsatility.[42] Nutritional deficits, signaling low energy availability through pathways like AMPK activation, further suppress GnRH release, while stress-induced cortisol elevation from the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reinforces this inhibition.[44] The primary role of anestrus is to promote energy conservation, allowing mammals to allocate resources toward survival rather than reproduction during periods of environmental adversity, such as food scarcity or harsh weather in non-breeding seasons.[42] This adaptive strategy ensures that breeding resumes only when conditions favor offspring viability, as seen in temperate species like sheep and hamsters.[44]Hormonal Regulation

Major Hormones Involved

The estrous cycle in mammals is orchestrated by a coordinated network of hormones that regulate follicular development, ovulation, and preparation for potential pregnancy. These hormones originate from the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary gland, ovaries, and uterus, with their pulsatile secretion driving the cyclic changes in reproductive physiology. Key players include gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol (the primary estrogen), progesterone, and prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α).[45] Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is secreted by neurons in the hypothalamus in a pulsatile manner, serving as the master regulator of the reproductive axis. It stimulates the anterior pituitary to release FSH and LH, thereby initiating and synchronizing ovarian events across the cycle phases. Disruptions in GnRH pulsatility can lead to irregular estrous cycles in various species.[45][46] Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), produced by gonadotroph cells in the anterior pituitary, promotes the growth and maturation of ovarian follicles during the early stages of the cycle. FSH acts on granulosa cells to enhance follicular development and stimulate the production of estrogens, setting the stage for subsequent ovulation. Levels of FSH typically rise at the onset of the cycle to recruit multiple follicles, with the dominant one selected for further growth.[47][48] Luteinizing hormone (LH), also secreted from the anterior pituitary, plays a pivotal role in triggering ovulation and supporting luteal function. A surge in LH, induced by rising estrogen levels, causes the rupture of the mature follicle and the release of the oocyte, typically occurring around the estrus phase. Post-ovulation, LH maintains the corpus luteum, ensuring progesterone production to sustain the luteal phase.[49][50] Estradiol, the predominant form of estrogen, is synthesized by granulosa cells in developing ovarian follicles under the influence of FSH. It exerts positive feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary to induce the LH surge, promotes endometrial proliferation during proestrus, and elicits behavioral estrus in females. Peak estradiol levels correlate with receptivity to mating and prepare the reproductive tract for fertilization.[1][49] Progesterone is primarily produced by the corpus luteum following ovulation, induced by LH. It maintains the uterine environment during the luteal phase (diestrus), inhibits further follicular development, and supports early pregnancy if conception occurs. Declining progesterone levels signal the regression of the corpus luteum, allowing the cycle to restart.[51][52] Prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α), synthesized by the uterine endometrium, is crucial for luteolysis at the end of the luteal phase. Released in pulses around days 16-18 of the cycle in species like cattle, it induces the functional and structural breakdown of the corpus luteum, thereby reducing progesterone and facilitating the return to follicular development. This process ensures cyclic fertility in non-pregnant animals.[53]Molecular Mechanisms

The molecular mechanisms governing the estrous cycle operate primarily through receptor-mediated signaling and transcriptional regulation at the cellular level. The gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor, a prototypical G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), facilitates the pulsatile release of GnRH from hypothalamic neurons, activating downstream phospholipase C pathways to mobilize intracellular calcium and protein kinase C.[54] Similarly, the luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptors, also members of the GPCR superfamily, are expressed on granulosa and theca cells in the ovary, where they couple to Gs proteins to stimulate adenylate cyclase, elevating cyclic AMP levels and promoting steroidogenesis.[55] In parallel, estrogen and progesterone receptors function as nuclear receptors, translocating to the nucleus upon ligand binding to modulate chromatin structure and directly influence the transcription of target genes involved in reproductive tissue proliferation and differentiation.[56] Feedback loops at the molecular level ensure precise temporal control of the cycle. Positive feedback arises from escalating estrogen concentrations, which activate estrogen receptor alpha in kisspeptin neurons within the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, triggering a surge in GnRH and subsequent LH release to induce ovulation.[57] Conversely, negative feedback is exerted by progesterone binding to its nuclear receptors, which represses GnRH neuronal activity through inhibition of kisspeptin expression and enhancement of GABAergic tone, thereby suppressing gonadotropin secretion during the luteal phase.[58] Gene regulation drives the synthesis of key hormones and adapts the cycle to physiological demands. The CYP19A1 gene, encoding the aromatase enzyme, is transcriptionally activated in ovarian granulosa cells by FSH-induced cAMP signaling via phosphorylation of transcription factors such as CREB, converting androgens to estrogens essential for follicular maturation.[59] Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, further regulate reproductive gene expression during seasonal anestrus in mammals, silencing pathways like GnRH signaling in response to prolonged melatonin exposure under short photoperiods.[60] Recent investigations have highlighted novel molecular players in cycle dynamics. Melatonin, secreted by the pineal gland in response to photoperiod, modulates estrous onset in seasonal breeders through 2021 studies showing its binding to MT1/MT2 receptors in the hypothalamus, which alters epigenetic marks on clock genes like PER2 to synchronize reproductive timing. Additionally, microRNAs (miRNAs) contribute to luteolysis by post-transcriptionally repressing genes in the prostaglandin pathway. Disruptions in these mechanisms can precipitate reproductive pathologies. Inactivating mutations in the FSH receptor (FSHR) gene, such as those impairing G-protein coupling, disrupt follicular recruitment and estrogen production, resulting in irregular estrous cycles and infertility in female mammals, as observed in murine models with homozygous variants.[61]Variability and Influences

Cycle Length and Frequency

The estrous cycle length refers to the interval from the onset of one estrus to the onset of the next, typically encompassing the full sequence of phases driven by hormonal fluctuations and ovulation. In mammals, this duration varies widely across species, reflecting adaptations to reproductive strategies, with measurements often derived from behavioral observations, vaginal cytology, or hormonal assays in veterinary and research settings. For instance, the cycle is influenced by the rate of follicular development and corpus luteum maintenance, leading to consistent patterns in healthy adults but potential irregularities in other conditions.[37] Mammals exhibit different frequencies of estrous cycles based on annual reproductive patterns. Polyestrous species, such as cattle and pigs, experience continuous cycles throughout the year without prolonged anestrus, allowing multiple breeding opportunities. Seasonally polyestrous animals, like sheep and horses, restrict cycles to specific breeding seasons, typically aligned with environmental optima for offspring survival. Monoestrous mammals, including dogs and certain wild species like foxes, have only one or two cycles per year, with extended intervals between events to concentrate reproductive efforts. These classifications are determined by the number of cycles annually and the presence of anestrous periods.[62] Cycle consistency can be affected by internal factors such as age and health status. In younger animals, cycles may be shorter or more irregular due to immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis development, as observed in peripubertal rodents and livestock where initial cycles often deviate from adult norms. Advancing age in adults can lead to progressively shortened cycles or increased variability, linked to declining ovarian reserve and altered hormone dynamics, particularly in mice and primates. Health conditions, including nutritional deficiencies or systemic diseases, further disrupt cycle regularity by impacting hormone production or follicular health, resulting in prolonged or skipped cycles. These influences underscore the importance of monitoring for reproductive management in veterinary practice.[63][64]| Species | Cycle Length (Average and Range) | Frequency Type |

|---|---|---|

| Rat | 4–5 days | Polyestrous |

| Mouse | 4–5 days | Polyestrous |

| Pig | 21 days (19–23 days) | Polyestrous |

| Cattle | 21 days (18–24 days) | Polyestrous |

| Sheep | 17 days (14–19 days) | Seasonally polyestrous |

| Horse | 21 days (19–22 days) | Seasonally polyestrous |

| Dog | 7 months (4–12 months) | Monoestrous (2 cycles/year) |