Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ruminant

View on Wikipedia

| Ruminants Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Clade: | Cetruminantia |

| Clade: | Ruminantiamorpha Spaulding et al., 2009 |

| Suborder: | Ruminantia Scopoli, 1777 |

| Infraorders | |

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microbial actions. The process, which takes place in the front part of the digestive system and therefore is called foregut fermentation, typically requires the fermented ingesta (known as cud) to be regurgitated and chewed again. The process of rechewing the cud to further break down plant matter and stimulate digestion is called rumination.[1][2] The word "ruminant" comes from the Latin ruminare, which means "to chew over again".

The roughly 200 species of ruminants include both domestic and wild species.[3] Ruminating mammals include cattle, all domesticated and wild bovines, goats, sheep, giraffes, deer, gazelles, and antelopes.[4] It has also been suggested that notoungulates also relied on rumination, as opposed to other atlantogenatans that rely on the more typical hindgut fermentation, though this is not entirely certain.[5]

Ruminants represent the most diverse group of living ungulates.[6] The suborder Ruminantia includes six different families: Tragulidae, Giraffidae, Antilocapridae, Cervidae, Moschidae, and Bovidae.[3]

Taxonomy and evolution

[edit]The first fossil ruminants appeared in the Early Eocene and were small, likely omnivorous, forest-dwellers.[7] Artiodactyls with cranial appendages first occur in the early Miocene.[7]

Phylogeny

[edit]Ruminantia is a crown group of ruminants within the order Artiodactyla, cladistically defined by Spaulding et al. as "the least inclusive clade that includes Bos taurus (cow) and Tragulus napu (mouse deer)". Ruminantiamorpha is a higher-level clade of artiodactyls, cladistically defined by Spaulding et al. as "Ruminantia plus all extinct taxa more closely related to extant members of Ruminantia than to any other living species."[8] This is a stem-based definition for Ruminantiamorpha, and is more inclusive than the crown group Ruminantia. As a crown group, Ruminantia only includes the last common ancestor of all extant (living) ruminants and their descendants (living or extinct), whereas Ruminantiamorpha, as a stem group, also includes more basal extinct ruminant ancestors that are more closely related to living ruminants than to other members of Artiodactyla. When considering only living taxa (neontology), this makes Ruminantiamorpha and Ruminantia synonymous, and only Ruminantia is used. Thus, Ruminantiamorpha is only used in the context of paleontology. Accordingly, Spaulding grouped some genera of the extinct family Anthracotheriidae within Ruminantiamorpha (but not in Ruminantia), but placed others within Ruminantiamorpha's sister clade, Cetancodontamorpha.[8]

Ruminantia's placement within Artiodactyla can be represented in the following cladogram:[9][10][11][12][13]

| Artiodactyla |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Within Ruminantia, the Tragulidae (mouse deer) are considered the most basal family,[14] with the remaining ruminants classified as belonging to the infraorder Pecora. Until the beginning of the 21st century, it was understood that the family Moschidae (musk deer) was sister to Cervidae. However, a 2003 phylogenetic study by Alexandre Hassanin (of National Museum of Natural History, France) and colleagues, based on mitochondrial and nuclear analyses, revealed that Moschidae and Bovidae form a clade sister to Cervidae. According to the study, Cervidae diverged from the Bovidae-Moschidae clade 27 to 28 million years ago.[15] The following cladogram is based on a large-scale genome ruminant genome sequence study from 2019:[16]

Classification

[edit]- Order Artiodactyla

- Suborder Tylopoda: camels and llamas, 7 living species in 3 genera

- Suborder Suina: pigs and peccaries

- Suborder Cetruminantia: ruminants, whales and hippos

- Clade Ruminantia

- Infraorder Tragulina (paraphyletic)[17]

- Family †Leptomerycidae

- Family †Hypertragulidae

- Family †Praetragulidae

- Family †Gelocidae

- Family †Bachitheriidae

- Family Tragulidae: chevrotains, 6 living species in 4 genera

- Family †Archaeomerycidae

- Family †Lophiomerycidae

- Infraorder Pecora

- Family Cervidae: deer and moose, 49 living species in 16 genera

- Family †Palaeomerycidae

- Family †Dromomerycidae

- Family †Hoplitomerycidae

- Family †Climacoceratidae

- Family Giraffidae: giraffe and okapi, 2 living species in 2 genera

- Family Antilocapridae: pronghorn, one living species in one genus

- Family Moschidae: musk deer, 4 living species in one genus

- Family Bovidae: cattle, goats, sheep, and antelope, 143 living species in 53 genera

- Infraorder Tragulina (paraphyletic)[17]

- Clade Ruminantia

Digestive system of ruminants

[edit]Hofmann and Stewart divided ruminants into three major categories based on their feed type and feeding habits: concentrate selectors, intermediate types, and grass/roughage eaters, with the assumption that feeding habits in ruminants cause morphological differences in their digestive systems, including salivary glands, rumen size, and rumen papillae.[18][19] However, Woodall found that there is little correlation between the fiber content of a ruminant's diet and morphological characteristics, meaning that the categorical divisions of ruminants by Hofmann and Stewart warrant further research.[20]

Also, some mammals are pseudoruminants, which have a three-compartment stomach instead of four like ruminants. The Hippopotamidae (comprising hippopotamuses) are well-known examples. Pseudoruminants, like traditional ruminants, are foregut fermentors and most ruminate or chew cud. However, their anatomy and method of digestion differs significantly from that of a four-chambered ruminant.[4]

Monogastric herbivores, such as rhinoceroses, horses, guinea pigs, and rabbits, are not ruminants, as they have a simple single-chambered stomach. Being hindgut fermenters, these animals ferment cellulose in an enlarged cecum. In smaller hindgut fermenters of the order Lagomorpha (rabbits, hares, and pikas), and Caviomorph rodents (Guinea pigs, capybaras, etc.), material from the cecum is formed into cecotropes, passed through the large intestine, expelled and subsequently reingested to absorb nutrients in the cecotropes.

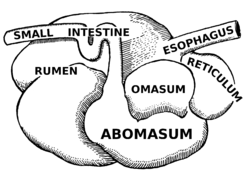

The primary difference between ruminants and nonruminants is that ruminants' stomachs have four compartments:

- rumen—primary site of microbial fermentation

- reticulum

- omasum—receives chewed cud, and absorbs volatile fatty acids

- abomasum—true stomach

The first two chambers are the rumen and the reticulum. These two compartments make up the fermentation vat and are the major site of microbial activity. Fermentation is crucial to digestion because it breaks down complex carbohydrates, such as cellulose, and enables the animal to use them. Microbes function best in a warm, moist, anaerobic environment with a temperature range of 37.7 to 42.2 °C (99.9 to 108.0 °F) and a pH between 6.0 and 6.4. Without the help of microbes, ruminants would not be able to use nutrients from forages.[22] The food is mixed with saliva and separates into layers of solid and liquid material.[23] Solids clump together to form the cud or bolus.

The cud is then regurgitated and chewed to completely mix it with saliva and to break down the particle size. Smaller particle size allows for increased nutrient absorption. Fiber, especially cellulose and hemicellulose, is primarily broken down in these chambers by microbes (mostly bacteria, as well as some protozoa, fungi, and yeast) into the three volatile fatty acids (VFAs): acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid. Protein and nonstructural carbohydrate (pectin, sugars, and starches) are also fermented. Saliva is very important because it provides liquid for the microbial population, recirculates nitrogen and minerals, and acts as a buffer for the rumen pH.[22] The type of feed the animal consumes affects the amount of saliva that is produced.

Though the rumen and reticulum have different names, they have very similar tissue layers and textures, making it difficult to visually separate them. They also perform similar tasks. Together, these chambers are called the reticulorumen. The degraded digesta, which is now in the lower liquid part of the reticulorumen, then passes into the next chamber, the omasum. This chamber controls what is able to pass into the abomasum. It keeps the particle size as small as possible in order to pass into the abomasum. The omasum also absorbs volatile fatty acids and ammonia.[22]

After this, the digesta is moved to the true stomach, the abomasum. This is the gastric compartment of the ruminant stomach. The abomasum is the direct equivalent of the monogastric stomach, and digesta is digested here in much the same way. This compartment releases acids and enzymes that further digest the material passing through. This is also where the ruminant digests the microbes produced in the rumen.[22] Digesta is finally moved into the small intestine, where the digestion and absorption of nutrients occurs. The small intestine is the main site of nutrient absorption. The surface area of the digesta is greatly increased here because of the villi that are in the small intestine. This increased surface area allows for greater nutrient absorption. Microbes produced in the reticulorumen are also digested in the small intestine. After the small intestine is the large intestine. The major roles here are breaking down mainly fiber by fermentation with microbes, absorption of water (ions and minerals) and other fermented products, and also expelling waste.[24] Fermentation continues in the large intestine in the same way as in the reticulorumen.

Only small amounts of glucose are absorbed from dietary carbohydrates. Most dietary carbohydrates are fermented into VFAs in the rumen. The glucose needed as energy for the brain and for lactose and milk fat in milk production, as well as other uses, comes from nonsugar sources, such as the VFA propionate, glycerol, lactate, and protein. The VFA propionate is used for around 70% of the glucose and glycogen produced and protein for another 20% (50% under starvation conditions).[25][26]

Abundance, distribution, and domestication

[edit]Wild ruminants number at least 75 million[27] and are native to all continents except Antarctica and Australia.[3] Nearly 90% of all species are found in Eurasia and Africa.[27] Species inhabit a wide range of climates (from tropic to arctic) and habitats (from open plains to forests).[27]

The population of domestic ruminants is greater than 3.5 billion, with cattle, sheep, and goats accounting for about 95% of the total population. Goats were domesticated in the Near East circa 8000 BC. Most other species were domesticated by 2500 BC., either in the Near East or southern Asia.[27]

Ruminant physiology

[edit]Ruminating animals have various physiological features that enable them to survive in nature. One feature of ruminants is their continuously growing teeth. During grazing, the silica content in forage causes abrasion of the teeth. This is compensated for by continuous tooth growth throughout the ruminant's life, as opposed to humans or other nonruminants, whose teeth stop growing after a particular age. Most ruminants do not have upper incisors; instead, they have a thick dental pad to thoroughly chew plant-based food.[28] Another feature of ruminants is the large ruminal storage capacity that gives them the ability to consume feed rapidly and complete the chewing process later. This is known as rumination, which consists of the regurgitation of feed, rechewing, resalivation, and reswallowing. Rumination reduces particle size, which enhances microbial function and allows the digesta to pass more easily through the digestive tract.[22]

Unlike camelids, ruminants copulate in a standing position and are not Induced ovulators.[29]

Rumen microbiology

[edit]Vertebrates lack the ability to hydrolyse the beta [1–4] glycosidic bond of plant cellulose due to the lack of the enzyme cellulase. Thus, ruminants completely depend on the microbial flora, present in the rumen or hindgut, to digest cellulose. Digestion of food in the rumen is primarily carried out by the rumen microflora, which contains dense populations of several species of bacteria, protozoa, sometimes yeasts and other fungi – 1 ml of rumen is estimated to contain 10–50 billion bacteria and 1 million protozoa, as well as several yeasts and fungi.[30]

Since the environment inside a rumen is anaerobic, most of these microbial species are obligate or facultative anaerobes that can decompose complex plant material, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, starch, and proteins. The hydrolysis of cellulose results in sugars, which are further fermented to acetate, lactate, propionate, butyrate, carbon dioxide, and methane.

As bacteria conduct fermentation in the rumen, they consume about 10% of the carbon, 60% of the phosphorus, and 80% of the nitrogen that the ruminant ingests.[31] To reclaim these nutrients, the ruminant then digests the bacteria in the abomasum. The enzyme lysozyme has adapted to facilitate digestion of bacteria in the ruminant abomasum.[32] Pancreatic ribonuclease also degrades bacterial RNA in the ruminant small intestine as a source of nitrogen.[33]

During grazing, ruminants produce large amounts of saliva – estimates range from 100 to 150 litres of saliva per day for a cow.[34] The role of saliva is to provide ample fluid for rumen fermentation and to act as a buffering agent.[35] Rumen fermentation produces large amounts of organic acids, thus maintaining the appropriate pH of rumen fluids is a critical factor in rumen fermentation. After digesta passes through the rumen, the omasum absorbs excess fluid so that digestive enzymes and acid in the abomasum are not diluted.[17]

Tannin toxicity in ruminant animals

[edit]Tannins are phenolic compounds that are commonly found in plants. Found in the leaf, bud, seed, root, and stem tissues, tannins are widely distributed in many different species of plants. Tannins are separated into two classes: hydrolysable tannins and condensed tannins. Depending on their concentration and nature, either class can have adverse or beneficial effects. Tannins can be beneficial, having been shown to increase milk production, wool growth, ovulation rate, and lambing percentage, as well as reducing bloat risk and reducing internal parasite burdens.[36]

Tannins can be toxic to ruminants, in that they precipitate proteins, making them unavailable for digestion, and they inhibit the absorption of nutrients by reducing the populations of proteolytic rumen bacteria.[36][37] Very high levels of tannin intake can produce toxicity that can even cause death.[38] Animals that normally consume tannin-rich plants can develop defensive mechanisms against tannins, such as the strategic deployment of lipids and extracellular polysaccharides that have a high affinity to binding to tannins.[36] Some ruminants (goats, deer, elk, moose) are able to consume food high in tannins (leaves, twigs, bark) due to the presence in their saliva of tannin-binding proteins.[39]

Religious importance

[edit]The Law of Moses in the Bible allowed the eating of some mammals that had cloven hooves (i.e. members of the order Artiodactyla) and "that chew the cud",[40] a stipulation preserved to this day in Jewish dietary laws and also the dietary laws of the Samaritans, the Sacred Name movements and of denominations that follow the same dietary laws, such as the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahado Church, the Seventh Day Adventists, the Philadelphia Church of God, and some other denominations.

Other uses

[edit]The verb 'to ruminate' has been extended metaphorically to mean to ponder thoughtfully or to meditate on some topic. Similarly, ideas may be 'chewed on' or 'digested'. 'Chew the cud', or 'Chew one's cud', is to reflect or meditate. In psychology, "rumination" refers to a pattern of thinking, and is unrelated to digestive physiology.

Ruminants and climate change

[edit]Methane is produced by a type of archaea, called methanogens, as described above within the rumen, and this methane is released to the atmosphere. The rumen is the major site of methane production in ruminants.[41] Methane is a strong greenhouse gas with a global warming potential of 86 compared to CO2 over a 20-year period.[42][43]

As a by-product of consuming cellulose, cattle belch out methane, there-by returning that carbon sequestered by plants back into the atmosphere. After about 10 to 12 years, that methane is broken down and converted back to CO2. Once converted to CO2, plants can again perform photosynthesis and fix that carbon back into cellulose. From here, cattle can eat the plants and the cycle begins once again. In essence, the methane belched from cattle is not adding new carbon to the atmosphere. Rather it is part of the natural cycling of carbon through the biogenic carbon cycle.[44]

In 2010, enteric fermentation accounted for 43% of the total greenhouse gas emissions from all agricultural activity in the world,[45] 26% of the total greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural activity in the U.S., and 22% of the total U.S. methane emissions.[46] The meat from domestically raised ruminants has a higher carbon equivalent footprint than other meats or vegetarian sources of protein based on a global meta-analysis of lifecycle assessment studies.[47] Methane production by meat animals, principally ruminants, is estimated 15–20% global production of methane, unless the animals were hunted in the wild.[48][49] The current U.S. domestic beef and dairy cattle population is around 90 million head, approximately 50% higher than the peak wild population of American bison of 60 million head in the 1700s,[50] which primarily roamed the part of North America that now makes up the United States.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Rumination: The process of foregut fermentation". Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Ruminant Digestive System" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Fernández, Manuel Hernández; Vrba, Elisabeth S. (1 May 2005). "A complete estimate of the phylogenetic relationships in Ruminantia: a dated species-level supertree of the extant ruminants". Biological Reviews. 80 (2): 269–302. doi:10.1017/s1464793104006670. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 15921052. S2CID 29939520.

- ^ a b Fowler, M.E. (2010). "Medicine and Surgery of Camelids", Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. Chapter 1 General Biology and Evolution addresses the fact that camelids (including camels and llamas) are not ruminants, pseudo-ruminants, or modified ruminants.

- ^ Richard F. Kay, M. Susana Bargo, Early Miocene Paleobiology in Patagonia: High-Latitude Paleocommunities of the Santa Cruz Formation, Cambridge University Press, 11 October 2012

- ^ "Suborder Ruminatia, the Ultimate Ungulate".

- ^ a b DeMiguel, D.; Azanza, B.; Morales, J. (2014). "Key Innovations in Ruminant Evolution: A Paleontological Perspective". Integrative Zoology. 9 (4): 412–433. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12080. PMID 24148672.

- ^ a b Spaulding, M; O'Leary, MA; Gatesy, J (2009). "Relationships of Cetacea (Artiodactyla) among mammals: increased taxon sampling alters interpretations of key fossils and character evolution". PLOS ONE. 4 (9) e7062. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7062S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007062. PMC 2740860. PMID 19774069.

- ^ Beck, N.R. (2006). "A higher-level MRP supertree of placental mammals". BMC Evol Biol. 6: 93. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-6-93. PMC 1654192. PMID 17101039.

- ^ O'Leary, M.A.; Bloch, J.I.; Flynn, J.J.; Gaudin, T.J.; Giallombardo, A.; Giannini, N.P.; Goldberg, S.L.; Kraatz, B.P.; Luo, Z.-X.; Meng, J.; Ni, X.; Novacek, M.J.; Perini, F.A.; Randall, Z.S.; Rougier, G.W.; Sargis, E.J.; Silcox, M.T.; Simmons, N.B.; Spaulding, M.; Velazco, P.M.; Weksler, M.; Wible, J.R.; Cirranello, A.L. (2013). "The Placental Mammal Ancestor and the Post-K-Pg Radiation of Placentals". Science. 339 (6120): 662–667. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..662O. doi:10.1126/science.1229237. hdl:11336/7302. PMID 23393258. S2CID 206544776.

- ^ Song, S.; Liu, L.; Edwards, S.V.; Wu, S. (2012). "Resolving conflict in eutherian mammal phylogeny using phylogenomics and the multispecies coalescent model". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (37): 14942–14947. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10914942S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211733109. PMC 3443116. PMID 22930817.

- ^ dos Reis, M.; Inoue, J.; Hasegawa, M.; Asher, R.J.; Donoghue, P.C.J.; Yang, Z. (2012). "Phylogenomic datasets provide both precision and accuracy in estimating the timescale of placental mammal phylogeny". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1742): 3491–3500. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0683. PMC 3396900. PMID 22628470.

- ^ Upham, N.S.; Esselstyn, J.A.; Jetz, W. (2019). "Inferring the mammal tree: Species-level sets of phylogenies for questions in ecology, evolution, and conservation". PLOS Biology. 17 (12) e3000494. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000494. PMC 6892540. PMID 31800571.(see e.g. Fig S10)

- ^ Kulemzina, Anastasia I.; Yang, Fengtang; Trifonov, Vladimir A.; Ryder, Oliver A.; Ferguson-Smith, Malcolm A.; Graphodatsky, Alexander S. (2011). "Chromosome painting in Tragulidae facilitates the reconstruction of Ruminantia ancestral karyotype". Chromosome Research. 19 (4): 531–539. doi:10.1007/s10577-011-9201-z. ISSN 0967-3849. PMID 21445689. S2CID 8456507.

- ^ Hassanin, A.; Douzery, E. J. P. (2003). "Molecular and morphological phylogenies of Ruminantia and the alternative position of the Moschidae". Systematic Biology. 52 (2): 206–28. doi:10.1080/10635150390192726. PMID 12746147.

- ^ Chen, L.; Qiu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, K. (2019). "Large-scale ruminant genome sequencing provides insights into their evolution and distinct traits". Science. 364 (6446) eaav6202. Bibcode:2019Sci...364.6202C. doi:10.1126/science.aav6202. PMID 31221828.

- ^ a b Clauss, M.; Rossner, G. E. (2014). "Old world ruminant morphophysiology, life history, and fossil record: exploring key innovations of a diversification sequence" (PDF). Annales Zoologici Fennici. 51 (1–2): 80–94. doi:10.5735/086.051.0210. S2CID 85347098.

- ^ Ditchkoff, S. S. (2000). "A decade since "diversification of ruminants": has our knowledge improved?" (PDF). Oecologia. 125 (1): 82–84. Bibcode:2000Oecol.125...82D. doi:10.1007/PL00008894. PMID 28308225. S2CID 23923707. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011.

- ^ Reinhold R Hofmann, 1989."Evolutionary steps of ecophysiological and diversification of ruminants: a comparative view of their digestive system". Oecologia, 78:443–457

- ^ Woodall, P. F. (1 June 1992). "An evaluation of a rapid method for estimating digestibility". African Journal of Ecology. 30 (2): 181–185. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1992.tb00492.x. ISSN 1365-2028.

- ^ Russell, J. B. 2002. Rumen Microbiology and its role In Ruminant Nutrition.

- ^ a b c d e Rickard, Tony (2002). Dairy Grazing Manual. MU Extension, University of Missouri-Columbia. pp. 7–8.

- ^ "How do ruminants digest?". OpenLearn. The Open University. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Meyer. Class Lecture. Animal Nutrition. University of Missouri-Columbia, MO. 16 September 2016

- ^ William O. Reece (2005). Functional Anatomy and Physiology of Domestic Animals, pages 357–358 ISBN 978-0-7817-4333-4

- ^ Colorado State University, Hypertexts for Biomedical Science: Nutrient Absorption and Utilization in Ruminants Archived 19 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Hackmann. T. J., and Spain, J. N. 2010."Ruminant ecology and evolution: Perspectives useful to livestock research and production". Journal of Dairy Science, 93:1320–1334

- ^ "Dental Anatomy of Ruminants".

- ^ Duncanson, Graham R. (29 February 2024). Farm Animal Medicine and Surgery for Small Animal Veterinarians, 2nd Edition. CABI. ISBN 978-1-80062-504-4.

- ^ "Fermentation Microbiology and Ecology". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ Callewaert, L.; Michiels, C. W. (2010). "Lysozymes in the animal kingdom". Journal of Biosciences. 35 (1): 127–160. doi:10.1007/S12038-010-0015-5. PMID 20413917. S2CID 21198203.

- ^ Irwin, D. M.; Prager, E. M.; Wilson, A. C. (1992). "Evolutionary genetics of ruminant lysozymes". Animal Genetics. 23 (3): 193–202. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.1992.tb00131.x. PMID 1503255.

- ^ Jermann, T. M.; Opitz, J. G.; Stackhouse, J.; Benner, S. A. (1995). "Reconstructing the evolutionary history of the artiodactyl ribonuclease superfamily" (PDF). Nature. 374 (6517): 57–59. Bibcode:1995Natur.374...57J. doi:10.1038/374057a0. PMID 7532788. S2CID 4315312. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2019.

- ^ Reid, J.T.; Huffman, C.F. (1949). "Some physical and chemical properties of Bovine saliva which may affect rumen digestion and synthesis". Journal of Dairy Science. 32 (2): 123–132. doi:10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(49)92019-6.

- ^ "Rumen Physiology and Rumination". Archived from the original on 29 January 1998.

- ^ a b c B.R Min, et al (2003) The effect of condensed tannins on the nutrition and health of ruminants fed fresh temperate forages: a review Animal Feed Science and Technology 106(1):3–19

- ^ Bate-Smith and Swain (1962). "Flavonoid compounds". In Florkin M., Mason H.S. (ed.). Comparative biochemistry. Vol. III. New York: Academic Press. pp. 75–809.

- ^ "'Tannins: fascinating but sometimes dangerous molecules' [Cornell University Department of Animal Science? (c) 2018]".

- ^ Austin, PJ; et al. (1989). "Tannin-binding proteins in saliva of deer and their absence in saliva of sheep and cattle". J Chem Ecol. 15 (4): 1335–47. doi:10.1007/BF01014834. PMID 24272016. S2CID 32846214.

- ^ Leviticus 11:3

- ^ Asanuma, Narito; Iwamoto, Miwa; Hino, Tsuneo (1999). "Effect of the Addition of Fumarate on Methane Production by Ruminal Microorganisms in Vitro". Journal of Dairy Science. 82 (4): 780–787. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(99)75296-3. PMID 10212465.

- ^ IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Table 8.7, Chap. 8, pp. 8–58 (PDF)

- ^ Shindell, D. T.; Faluvegi, G.; Koch, D. M.; Schmidt, G. A.; Unger, N.; Bauer, S. E. (2009). "Improved Attribution of Climate Forcing to Emissions". Science. 326 (5953): 716–728. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..716S. doi:10.1126/science.1174760. PMID 19900930. S2CID 30881469. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023 – via Zenodo.

- ^ Werth, Samantha (19 February 2020). "The Biogenic Carbon Cycle and Cattle". CLEAR Center. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2013) "FAO Statistical Yearbook 2013 World Food and Agriculture – Sustainability dimensions". Data in Table 49 on p. 254.

- ^ "Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2014". US EPA. 2016. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Pete Smith; Helmut Haberl; Stephen A. Montzka; Clive McAlpine & Douglas H. Boucher. 2014. "Ruminants, climate change and climate policy". Nature Climate Change. Volume 4 No. 1. pp. 2–5.

- ^ Cicerone, R. J., and R. S. Oremland. 1988 "Biogeochemical Aspects of Atmospheric Methane"

- ^ Yavitt, J. B. 1992. Methane, biogeochemical cycle. pp. 197–207 in Encyclopedia of Earth System Science, Vol. 3. Acad.Press, London.

- ^ Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (January 1965). "The American Buffalo". Conservation Note. 12.

External links

[edit]- Digestive Physiology of Herbivores – Colorado State University (Last updated on 13 July 2006)

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Ruminant". Encyclopædia Britannica, Invalid Date, https://www.britannica.com/animal/ruminant. Accessed 22 February 2021.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Ruminant

View on GrokipediaDefinition and General Characteristics

Anatomical and Physiological Traits

Ruminants exhibit a distinctive stomach morphology characterized by four interconnected chambers: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. This anatomical configuration supports the compartmentalized processing of ingested forage, with the rumen and reticulum forming a capacious foregut reservoir, the omasum featuring leaf-like folds, and the abomasum functioning as the glandular "true" stomach.[2][7][8] Their dentition is specialized for herbivory, lacking upper incisors and canines in favor of a tough, fibrous dental pad against which the mandibular incisors crop vegetation. The premolars and molars display selenodont cusps—crescent-shaped ridges suited for grinding fibrous plant matter—and exhibit hypsodonty, with roots that remain open for lifelong eruption to compensate for wear from silica-laden grasses.[8] Locomotor adaptations include even-toed (cloven) hooves, where weight is distributed primarily on digits III and IV, with digits II and V reduced to dewclaws; this paraxonic foot structure enhances stability and propulsion on uneven terrain conducive to foraging. Body masses vary substantially across taxa, reflecting ecological niches from understory browsers to open-plain grazers. Many species bear permanent horns (keratin-sheathed bony projections, as in bovids) or deciduous antlers (velvet-covered in cervids), which structurally reinforce the cranium and physiologically integrate with seasonal hormonal cycles to facilitate defense and intraspecific rivalry.[9][10]Behavioral Patterns Including Rumination

Rumination in ruminants involves the regurgitation of a bolus of partially digested feed, known as cud, from the rumen back to the mouth for re-chewing, followed by re-insalivation and re-swallowing.[7] This cyclic process mechanically reduces particle size of fibrous plant material, increasing surface area exposure and facilitating subsequent microbial breakdown in the rumen without relying on enzymatic digestion alone.[11] Each rumination bout typically lasts 30 to 60 seconds, with cycles of rumen contractions occurring 1 to 3 times per minute to propel the cud upward.[11] In domestic species such as cattle, daily rumination time averages 450 to 550 minutes, equivalent to 6 to 8 hours or 35 to 40 percent of the day, though this varies with diet quality—longer durations occur with high-fiber, low-digestibility forages like straw, which can exceed 500 minutes, compared to shorter times with hay at around 387 minutes.[2] [12] [13] Rumination predominantly takes place during resting phases, including nighttime and afternoon periods, allowing animals to process ingested forage while minimizing energy expenditure on locomotion.[14] Ruminant foraging behaviors emphasize selective grazing and browsing on high-fiber, structurally complex vegetation, such as grasses and woody plants, which aligns with their reliance on microbial fermentation for energy extraction.[15] Sheep and goats, for instance, actively select plant species and parts based on nutritional content, favoring those with moderate digestibility (60 to 69 percent dry matter) to optimize intake rates while coping with rumen fill limitations from fibrous diets.[16] [17] This selectivity reduces ingestion of low-quality or toxic forages and supports sustained nutrient acquisition in heterogeneous environments. Social structures in ruminants, particularly bovids, feature stable dominance hierarchies established through agonistic interactions like butting and pushing, which determine priority access to forage, water, and resting sites.[18] In cattle herds, higher-ranked individuals displace subordinates, minimizing intra-group aggression while influencing resource distribution—dominant cows secure better patches, potentially gaining 10 to 20 percent more intake under competitive conditions.[19] Herd formation enhances predator avoidance through collective vigilance and the dilution effect, where individuals in groups of 10 or more experience reduced per-capita attack rates compared to solitary animals.[20] In wild populations, such as deer or antelope, these dynamics promote synchronized resting for rumination during low-predation windows, often crepuscular or nocturnal, to balance digestive needs with survival imperatives.[20]Evolutionary Origins and Taxonomy

Phylogenetic and Fossil Evidence

Ruminants emerged during the Eocene epoch approximately 50 million years ago from small-bodied (<5 kg), forest-dwelling artiodactyl ancestors that exhibited omnivorous tendencies and rudimentary foregut fermentation.[21] The earliest definitive ruminant fossils, such as Archaeomeryx from middle Eocene deposits in Asia dated to about 44 million years ago, support an origin in Paleogene forests of eastern Asia, with subsequent dispersals westward into Europe by the late Eocene.[22][23] Primitive forms like gelocids (Gelocus, Lophiomeryx) from late Eocene to Oligocene strata in Europe and Asia display mosaic traits, including selenodont dentition adapted for browsing soft vegetation and early astragalar features indicative of enhanced cursoriality, bridging basal artiodactyls to more derived pecorans.[24] Phylogenetic reconstructions using mitochondrial DNA and multi-calibrated molecular clocks confirm Ruminantia's monophyly within Artiodactyla, with divergence from tylopod ancestors (e.g., camels) predating the Eocene-Oligocene transition and crown-group pecorans arising before 37 million years ago.[25][22] Total-evidence analyses integrating morphological and genetic data further resolve internal branches, highlighting rapid cladogenesis in the early Oligocene tied to climatic cooling and habitat fragmentation.[26] Genomic sequencing of 44 ruminant species in 2019 uncovered selective pressures on genes involved in rumen microbial symbiosis and volatile fatty acid metabolism, enabling efficient cellulose breakdown and fueling post-Eocene diversification into diverse niches.[27] Fossil dental wear patterns and microwear analyses reveal a Miocene shift from browser-dominated diets to grazing, driven by hypsodont tooth crown elongation that resisted abrasion from expanding C4 grasslands around 8-7 million years ago, though ruminant hypsodonty lagged behind equids, reflecting slower adaptive responses to abrasive silica phytoliths.[28][29] This dietary innovation, corroborated by stable carbon isotope records in tooth enamel, underscores how Miocene aridification and grass biome proliferation causally amplified ruminant ecological success without implying uniform adaptation across lineages.[30]Classification into Families and Suborders

The suborder Ruminantia, within the order Artiodactyla, comprises true ruminants characterized by foregut fermentation and multilobular stomachs, excluding pseudoruminants like camels in Tylopoda.[31] It is divided into two monophyletic infraorders based on molecular phylogenies: Tragulina, the basal group, and Pecora, the derived clade encompassing higher ruminants. Genomic sequencing of representatives from all families has reinforced this bipartition, with Tragulina diverging early from Pecora around 50-60 million years ago via molecular clock estimates calibrated against fossil constraints.[27] Tragulina includes a single family, Tragulidae (chevrotains or mouse-deer), with four genera and approximately 10 species, such as Tragulus javanicus. These small, hornless artiodactyls retain primitive traits like unfused tarsal bones and lack the cranial appendages typical of Pecora, supported by both morphological and mitochondrial DNA analyses showing their position as the outgroup to other ruminants.[27] Chromosome counts vary (e.g., 2n=48 in most species), but genetic data prioritize their isolation over solely anatomical classifications that once ambiguously linked them to other small ungulates.[32] Pecora unites five families through shared synapomorphies like fused carpal bones (magnum-trapezoid) and ruminant digestion refinements, totaling about 190 species. These include Moschidae (musk deer; 1 genus, 7 species, e.g., Moschus moschiferus, with tusk-like canine teeth and no antlers); Cervidae (deer; 16 genera, ~50 species, featuring antlers in males of most taxa and diverse chromosome numbers from 2n=46 to 70); Antilocapridae (pronghorn; 1 genus, 1 species, Antilocapra americana, unique for branched horns shed annually); Giraffidae (giraffes and okapi; 2 genera, 2-5 species depending on giraffe splitting, with elongated necks and ossicones); and Bovidae, the most diverse with ~50 genera and 143 species (e.g., cattle Bos taurus, sheep Ovis aries), defined by hollow unbranched horns in both sexes of many lineages.[32][27] Whole-genome comparisons, including from 44 species across these families, highlight Pecora's rapid diversification post-Oligocene, with DNA-based trees resolving interfamilial branching (e.g., Cervidae + Bovidae as sisters) more reliably than morphology alone, which had historically conflated groups like Antilocapridae with Bovidae.[27] Variable karyotypes (e.g., 2n=30 in giraffes, 60 in cattle) and retrotransposon insertions further corroborate these relationships empirically.[33]| Infraorder | Family | Genera | Species (approx.) | Key Taxonomic Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tragulina | Tragulidae | 4 | 10 | Primitive dentition, no cranial appendages; 2n≈48[27] |

| Pecora | Moschidae | 1 | 7 | Elongated canines; 2n=46-48[32] |

| Pecora | Cervidae | 16 | 50 | Antlers (shed); variable 2n=46-70[27] |

| Pecora | Antilocapridae | 1 | 1 | Branched, deciduous horns; 2n=58[32] |

| Pecora | Giraffidae | 2 | 2-5 | Ossicones, extreme cervical elongation; 2n=30[27] |

| Pecora | Bovidae | ~50 | 143 | Persistent hollow horns; diverse 2n (e.g., 60 in cattle)[32] |