Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

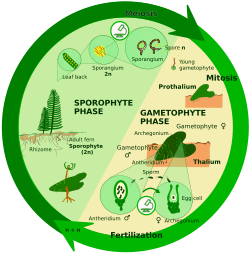

Biological life cycle

View on Wikipedia

In biology, a biological life cycle (or just life cycle when the biological context is clear) is a series of stages of the life of an organism, that begins as a zygote, often in an egg, and concludes as an adult that reproduces, producing an offspring in the form of a new zygote which then itself goes through the same series of stages, the process repeating in a cyclic fashion. In humans, the concept of a single generation is a cohort of people who, on average, are born around the same period of time,[1] it is related though distinct from the biological concept of generations.

"The concept is closely related to those of the life history, development and ontogeny, but differs from them in stressing renewal."[2][3] Transitions of form may involve growth, asexual reproduction, or sexual reproduction.

In some organisms, different "generations" of the species succeed each other during the life cycle. For plants and many algae, there are two multicellular stages, and the life cycle is referred to as alternation of generations. The term life history is often used, particularly for organisms such as the red algae which have three multicellular stages (or more), rather than two.[4]

Life cycles that include sexual reproduction involve alternating haploid (n) and diploid (2n) stages, i.e., a change of ploidy is involved. To return from a diploid stage to a haploid stage, meiosis must occur. In regard to changes of ploidy, there are three types of cycles:

- haplontic life cycle — the haploid stage is multicellular and the diploid stage is a single cell, meiosis is "zygotic".

- diplontic life cycle — the diploid stage is multicellular and haploid gametes are formed, meiosis is "gametic".

- haplodiplontic life cycle (also referred to as diplohaplontic, diplobiontic, or dibiontic life cycle) — multicellular diploid and haploid stages occur, meiosis is "sporic".

The cycles differ in when mitosis (growth) occurs. Zygotic meiosis and gametic meiosis have one mitotic stage: mitosis occurs during the n phase in zygotic meiosis and during the 2n phase in gametic meiosis. Therefore, zygotic and gametic meiosis are collectively termed "haplobiontic" (single mitotic phase, not to be confused with haplontic). Sporic meiosis, on the other hand, has mitosis in two stages, both the diploid and haploid stages, termed "diplobiontic" (not to be confused with diplontic).[citation needed]

Discovery

[edit]The study of reproduction and development in organisms was carried out by many botanists and zoologists.

Wilhelm Hofmeister demonstrated that alternation of generations is a feature that unites plants, and published this result in 1851 (see plant sexuality).

Some terms (haplobiont and diplobiont) used for the description of life cycles were proposed initially for algae by Nils Svedelius, and then became used for other organisms.[5][6] Other terms (autogamy and gamontogamy) used in protist life cycles were introduced by Karl Gottlieb Grell.[7] The description of the complex life cycles of various organisms contributed to the disproof of the ideas of spontaneous generation in the 1840s and 1850s.[8]

Haplontic life cycle

[edit]

A zygotic meiosis is a meiosis of a zygote immediately after karyogamy, which is the fusion of two cell nuclei. This way, the organism ends its diploid phase and produces several haploid cells. These cells divide mitotically to form either larger, multicellular individuals, or more haploid cells. Two opposite types of gametes (e.g., male and female) from these individuals or cells fuse to become a zygote.

In the whole cycle, zygotes are the only diploid cell; mitosis occurs only in the haploid phase.

The individuals or cells as a result of mitosis are haplonts, hence this life cycle is also called haplontic life cycle. Haplonts include:

- In archaeplastidans: some green algae (e.g., Chlamydomonas, Zygnema, Chara)[9][10]

- In stramenopiles: some golden algae[9][10]

- In alveolates: many dinoflagellates, e.g., Ceratium, Gymnodinium, some apicomplexans (e.g., Plasmodium)[11]

- In rhizarians: some euglyphids,[12] ascetosporeans

- In excavates: some parabasalids[13]

- In amoebozoans: Dictyostelium[9][10]

- In opisthokonts: most fungi (some chytrids, zygomycetes, some ascomycetes, basidiomycetes)[9][10][14]

Diplontic life cycle

[edit]

In gametic meiosis, instead of immediately dividing meiotically to produce haploid cells, the zygote divides mitotically to produce a multicellular diploid individual or a group of more unicellular diploid cells. Cells from the diploid individuals then undergo meiosis to produce haploid cells or gametes. Haploid cells may divide again (by mitosis) to form more haploid cells, as in many yeasts, but the haploid phase is not the predominant life cycle phase. In most diplonts, mitosis occurs only in the diploid phase, i.e. gametes usually form quickly and fuse to produce diploid zygotes.[15]

In the whole cycle, gametes are usually the only haploid cells, and mitosis usually occurs only in the diploid phase.

The diploid multicellular individual is a diplont, hence a gametic meiosis is also called a diplontic life cycle. Diplonts are:

- In archaeplastidans: some green algae (e.g., Cladophora glomerata,[16] Acetabularia[9][10])

- In stramenopiles: some brown algae (the Fucales, however, their life cycle can also be interpreted as strongly heteromorphic-diplohaplontic, with a highly reduced gametophyte phase, as in the flowering plants),[17] some xanthophytes (e.g., Vaucheria),[18] most diatoms,[13] some oomycetes (e.g., Saprolegnia, Plasmopara viticola),[9][10] opalines,[13] some "heliozoans" (e.g., Actinophrys, Actinosphaerium)[13][19]

- In alveolates: ciliates[13]

- In excavates: some parabasalids[13]

- In opisthokonts: animals, some fungi (e.g., some ascomycetes)[9][10]

Haplodiplontic life cycle

[edit]

In sporic meiosis (also commonly known as intermediary meiosis), the zygote divides mitotically to produce a multicellular diploid sporophyte. The sporophyte creates spores via meiosis which also then divide mitotically producing haploid individuals called gametophytes. The gametophytes produce gametes via mitosis. In some plants the gametophyte is not only small-sized but also short-lived; in other plants and many algae, the gametophyte is the "dominant" stage of the life cycle.[20]

Haplodiplonts are:

- In archaeplastidans: red algae (which have two sporophyte generations), some green algae (e.g., Ulva), land plants[9][10]

- In stramenopiles: most brown algae[9][10]

- In rhizarians: many foraminiferans,[13] plasmodiophoromycetes[9][10]

- In amoebozoa: myxogastrids

- In opisthokonts: some fungi (some chytrids, some ascomycetes like the brewer's yeast)[9][10]

- Other eukaryotes: haptophytes[13]

Some animals have a sex-determination system called haplodiploid, but this is not related to the haplodiplontic life cycle.

Vegetative meiosis

[edit]Some red algae (such as Bonnemaisonia[21] and Lemanea) and green algae (such as Prasiola) have vegetative meiosis, also called somatic meiosis, which is a rare phenomenon.[22] Vegetative meiosis can occur in haplodiplontic and also in diplontic life cycles. The gametophytes remain attached to and part of the sporophyte. Vegetative (non-reproductive) diploid cells undergo meiosis, generating vegetative haploid cells. These undergo many mitosis, and produces gametes.

A different phenomenon, called vegetative diploidization, a type of apomixis, occurs in some brown algae (e.g., Elachista stellaris).[23] Cells in a haploid part of the plant spontaneously duplicate their chromosomes to produce diploid tissue.

Parasitic life cycle

[edit]Parasites depend on the exploitation of one or more hosts. Those that must infect more than one host species to complete their life cycles are said to have complex or indirect life cycles. Dirofilaria immitis, or the heartworm, has an indirect life cycle, for example. The microfilariae must first be ingested by a female mosquito, where it develops into the infective larval stage. The mosquito then bites an animal and transmits the infective larvae into the animal, where they migrate to the pulmonary artery and mature into adults.[24]

Those parasites that infect a single species have direct life cycles. An example of a parasite with a direct life cycle is Ancylostoma caninum, or the canine hookworm. They develop to the infective larval stage in the environment, then penetrate the skin of the dog directly and mature to adults in the small intestine.[25][verification needed]

If a parasite has to infect a given host in order to complete its life cycle, then it is said to be an obligate parasite of that host; sometimes, infection is facultative—the parasite can survive and complete its life cycle without infecting that particular host species. Parasites sometimes infect hosts in which they cannot complete their life cycles; these are accidental hosts.

A host in which parasites reproduce sexually is known as the definitive, final or primary host. In intermediate hosts, parasites either do not reproduce or do so asexually, but the parasite always develops to a new stage in this type of host. In some cases a parasite will infect a host, but not undergo any development, these hosts are known as paratenic[26] or transport hosts. The paratenic host can be useful in raising the chance that the parasite will be transmitted to the definitive host. For example, the cat lungworm (Aelurostrongylus abstrusus) uses a slug or snail as an intermediate host; the first stage larva enters the mollusk and develops to the third stage larva, which is infectious to the definitive host—the cat. If a mouse eats the slug, the third stage larva will enter the mouse's tissues, but will not undergo any development.[citation needed]

Evolution

[edit]The primitive type of life cycle probably had haploid individuals with asexual reproduction.[13] Bacteria and archaea exhibit a life cycle like this, and some eukaryotes apparently do too (e.g., Cryptophyta, Choanoflagellata, many Euglenozoa, many Amoebozoa, some red algae, some green algae, the imperfect fungi, some rotifers and many other groups, not necessarily haploid).[27] However, these eukaryotes probably are not primitively asexual, but have lost their sexual reproduction, or it just was not observed yet.[28][29] Many eukaryotes (including animals and plants) exhibit asexual reproduction, which may be facultative or obligate in the life cycle, with sexual reproduction occurring more or less frequently.[30]

Individual organisms participating in a biological life cycle ordinarily age and die, while cells from these organisms that connect successive life cycle generations (germ line cells and their descendants) are potentially immortal. The basis for this difference is a fundamental problem in biology. The Russian biologist and historian Zhores A. Medvedev[31] considered that the accuracy of genome replicative and other synthetic systems alone cannot explain the immortality of germlines. Rather Medvedev thought that known features of the biochemistry and genetics of sexual reproduction indicate the presence of unique information maintenance and restoration processes at the gametogenesis stage of the biological life cycle. In particular, Medvedev considered that the most important opportunities for information maintenance of germ cells are created by recombination during meiosis and DNA repair; he saw these as processes within the germ line cells that were capable of restoring the integrity of DNA and chromosomes from the types of damage that cause irreversible ageing in non-germ line cells, e.g. somatic cells.[31]

The ancestry of each present day cell presumably traces back, in an unbroken lineage for over 3 billion years to the origin of life. It is not actually cells that are immortal but multi-generational cell lineages.[32] The immortality of a cell lineage depends on the maintenance of cell division potential. This potential may be lost in any particular lineage because of cell damage, terminal differentiation as occurs in nerve cells, or programmed cell death (apoptosis) during development. Maintenance of cell division potential of the biological life cycle over successive generations depends on the avoidance and the accurate repair of cellular damage, particularly DNA damage. In sexual organisms, continuity of the germline over successive cell cycle generations depends on the effectiveness of processes for avoiding DNA damage and repairing those DNA damages that do occur. Sexual processes in eukaryotes provide an opportunity for effective repair of DNA damages in the germ line by homologous recombination.[32][33]

See also

[edit]- Generation time – Average time from one generation to another within the same population

- Parasexual cycle – Nonsexual mechanism for transferring genetic material without meiosis

- Parthenogenesis – Asexual reproduction without fertilization

- Metamorphosis – Profound change in body structure during the post-embryonic development of an organism

- Reproductive biology – Branch of biology studying reproduction

- Mitotic recombination – Type of genetic recombination

References

[edit]- ^ "Generational Insights and the Speed of Change". American Marketing Association. 2022-06-30. Archived from the original on 2021-04-11. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ Bell, Graham; Koufopanou, Vassiliki (1991). "The Architecture of the Life Cycle in Small Organisms". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 332 (1262): 81–89. Bibcode:1991RSPTB.332...81B. doi:10.1098/rstb.1991.0035. JSTOR 55494.

- ^ Rodrigues, Juliany Cola Fernandes; Godinho, Joseane Lima Prado; De Souza, Wanderley (2014). "Biology of Human Pathogenic Trypanosomatids: Epidemiology, Lifecycle and Ultrastructure". Proteins and Proteomics of Leishmania and Trypanosoma. Subcellular Biochemistry. Vol. 74. pp. 1–42. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7305-9_1. ISBN 978-94-007-7304-2. PMID 24264239.

- ^ Dixon, P.S. 1973. Biology of the Rhodophyta. Oliver & Boyd. ISBN 0 05 002485 X[page needed]

- ^ C. Skottsberg (1961), "Nils Eberhard Svedelius. 1873–1960", Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 7: 294–312, doi:10.1098/rsbm.1961.0023

- ^ Svedelius, N. 1931. Nuclear Phases and Alternation in the Rhodophyceae. Archived 2013-10-05 at the Wayback Machine In: Beihefte zum Botanischen Centralblatt. Band 48/1: 38–59.

- ^ Margulis, L (6 February 1996). "Archaeal-eubacterial mergers in the origin of Eukarya: phylogenetic classification of life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (3): 1071–1076. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.1071M. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.3.1071. PMC 40032. PMID 8577716.

- ^ Moselio Schaechter (2009). Encyclopedia of Microbiology. Academic Press. Volume 4, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Díaz, T.E.; Fernández-Carvajal, C.; Fernández, J.A. (2004). Curso de Botánica. Gijón: Trea.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Díaz González, Tomás; Fernandez-Carvajal Alvarez, Mª del Carmen; Fernández Prieto, José Antonio. "Botánica: Ciclos biológicos de vegetales". Departamento de Biología de Organismos y Sistemas, Universidad de Oviedo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 May 2020.

- ^ Sinden, R. E.; Hartley, R. H. (November 1985). "Identification of the Meiotic Division of Malarial Parasites". The Journal of Protozoology. 32 (4): 742–744. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb03113.x. PMID 3906103.

- ^ Lahr, Daniel J. G.; Parfrey, Laura Wegener; Mitchell, Edward A. D.; Katz, Laura A.; Lara, Enrique (22 July 2011). "The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1715): 2081–2090. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0289. PMC 3107637. PMID 21429931.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology: A Functional Evolutionary Approach. Thomson-Brooks/Cole. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ van den Hoek, Mann & Jahns 1995, p. 15.

- ^ Smith, Gilbert M. (1938). "Nuclear Phases and Alternation of Generations in the Chlorophyceae". Botanical Review. 4 (3): 132–139. Bibcode:1938BotRv...4..132S. doi:10.1007/BF02872350. ISSN 0006-8101. JSTOR 4353174.

- ^ O. P. Sharma. Textbook of Algae, p. 189

- ^ van den Hoek, Mann & Jahns 1995, p. 207.

- ^ van den Hoek, Mann & Jahns 1995, p. 124.

- ^ Bell, Graham (1988). Sex and Death in Protozoa: The History of Obsession. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-36141-5.

- ^ Bennici, Andrea (2008). "Origin and early evolution of land plants: Problems and considerations". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 1 (2): 212–218. doi:10.4161/cib.1.2.6987. ISSN 1942-0889. PMC 2686025. PMID 19513262.

- ^ Salvador Soler, Noemi; Gómez Garreta, Amelia; Antonia Ribera Siguan, M. (August 2009). "Somatic meiosis in the life history of Bonnemaisonia asparagoides and Bonnemaisonia clavata (Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta) from the Iberian peninsula". European Journal of Phycology. 44 (3): 381–393. Bibcode:2009EJPhy..44..381S. doi:10.1080/09670260902780782. S2CID 217511084.

- ^ van den Hoek, Mann & Jahns 1995, p. 82.

- ^ Lewis, Raymond J. (January 1996). "Chromosomes of the brown algae". Phycologia. 35 (1): 19–40. Bibcode:1996Phyco..35...19L. doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-35-1-19.1.

- ^ "VetFolio". www.vetfolio.com. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

- ^ Datz, Craig (2011). "Parasitic and Protozoal Diseases". Small Animal Pediatrics. pp. 154–160. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4160-4889-3.00019-X. ISBN 978-1-4160-4889-3.

- ^ Schmidt and Roberts. 1985. Foundations of Parasitology 3rd Ed. Times Mirror/Mosby College Publishing[page needed]

- ^ Heywood, P.; Magee, P.T. (1976). "Meiosis in protists. Some structural and physiological aspects of meiosis in algae, fungi, and protozoa". Bacteriological Reviews. 40 (1): 190–240. doi:10.1128/mmbr.40.1.190-240.1976. PMC 413949. PMID 773364.

- ^ Shehre-Banoo Malik; Arthur W. Pightling; Lauren M. Stefaniak; Andrew M. Schurko & John M. Logsdon Jr (2008). "An Expanded Inventory of Conserved Meiotic Genes Provides Evidence for Sex in Trichomonas vaginalis". PLOS ONE. 3 (8) e2879. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2879M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002879. PMC 2488364. PMID 18663385.

- ^ Speijer, Dave; Lukeš, Julius; Eliáš, Marek (21 July 2015). "Sex is a ubiquitous, ancient, and inherent attribute of eukaryotic life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (29): 8827–8834. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.8827S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1501725112. PMC 4517231. PMID 26195746.

- ^ Schön, Isa; Martens, Koen; Dijk, Peter van (2009). Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-90-481-2770-2.[page needed]

- ^ a b Medvedev, Zhores A. (1981). "On the immortality of the germ line: Genetic and biochemical mechanisms. A review". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 17 (4): 331–359. doi:10.1016/0047-6374(81)90052-X. PMID 6173551. S2CID 35719466.

- ^ a b Bernstein, C.; Bernstein, H.; Payne, C. (1999). "Cell Immortality: Maintenance of Cell Division Potential". Cell Immortalization. Progress in Molecular and Subcellular Biology. Vol. 24. pp. 23–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-06227-2_2. ISBN 978-3-642-08491-1. PMID 10547857.

- ^ Avise, John C. (October 1993). "Perspective: The evolutionary biology of aging, sexual reproduction, and DNA repair". Evolution. 47 (5): 1293–1301. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb02155.x. PMID 28564887. S2CID 29262885.

Sources

[edit]- van den Hoek, C.; Mann; Jahns, H. M. (1995). Algae: An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31687-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Bonner, John Tyler (1995). Life Cycles: Reflections of an Evolutionary Biologist. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00151-7.

- Valero, Myriam; Richerd, Sophie; Perrot, Véronique; Destombe, Christophe (January 1992). "Evolution of alternation of haploid and diploid phases in life cycles". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 7 (1): 25–29. Bibcode:1992TEcoE...7...25V. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(92)90195-H. PMID 21235940.

- Mable, Barbara K.; Otto, Sarah P. (1998). "The evolution of life cycles with haploid and diploid phases". BioEssays. 20 (6): 453–462. doi:10.1002/(sici)1521-1878(199806)20:6<453::aid-bies3>3.0.co;2-n. S2CID 11841044.