Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union

View on Wikipedia

The economic and monetary union (EMU) of the European Union is a group of policies aimed at converging the economies of member states of the European Union at three stages.

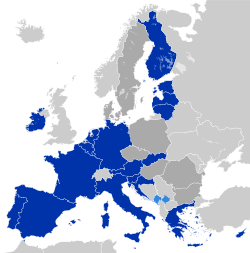

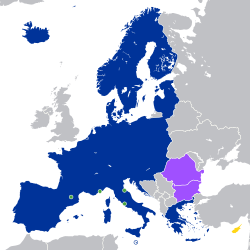

There are three stages of the EMU, each of which consists of progressively closer economic integration. Only once a state participates in the third stage it is permitted to adopt the euro as its official currency. As such, the third stage is largely synonymous with the eurozone. The euro convergence criteria are the set of requirements that needs to be fulfilled in order for a country to be approved to participate in the third stage. An important element of this is participation for a minimum of two years in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism ("ERM II"), in which candidate currencies demonstrate economic convergence by maintaining limited deviation from their target rate against the euro.

The EMU policies cover all European Union member states. All new EU member states must commit to participate in the third stage in their treaties of accession and are obliged to enter the third stage once they comply with all convergence criteria. Twenty EU member states, including most recently Croatia, have entered the third stage and have adopted the euro as their currency. Denmark, whose EU membership predates the introduction of the euro, has a legal opt-out from the EU Treaties and is thus not required to enter the third stage.[1][2]

History

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

Early developments

[edit]The idea of an economic and monetary union in Europe was first raised well before establishing the European Communities. For example, the Latin Monetary Union existed from 1865 to 1927.[3][4] In the League of Nations, Gustav Stresemann asked in 1929 for a European currency[5] against the background of an increased economic division due to a number of new nation states in Europe after World War I.

In 1957 at the European Forum Alpbach, De Nederlandsche Bank Governor Marius Holtrop argued that a common central-bank policy was necessary in a unified Europe, but his subsequent advocacy of a coordinated initiative by the European Community's central banks was met with skepticism from the heads of the National Bank of Belgium, Bank of France and Deutsche Bundesbank.[6]

A first concrete attempt to create an economic and monetary union between the members of the European Communities goes back to an initiative by the European Commission in 1969, which set out the need for "greater co-ordination of economic policies and monetary cooperation,"[7] which was followed by the decision of the Heads of State or Government at their summit meeting in The Hague in 1969 to draw up a plan by stages with a view to creating an economic and monetary union by the end of the 1970s.

On the basis of various previous proposals, an expert group chaired by Luxembourg's Prime Minister and Finance Minister, Pierre Werner, presented in October 1970 the first commonly agreed blueprint to create an economic and monetary union in three stages (Werner plan). The project experienced serious setbacks from the crises arising from the non-convertibility of the US dollar into gold in August 1971 (i.e., the collapse of the Bretton Woods System) and from rising oil prices in 1972. An attempt to limit the fluctuations of European currencies, using a snake in the tunnel, failed.

Delors Report

[edit]The debate on EMU was fully re-launched at the Hannover Summit in June 1988, when the ad hoc Delors Committee of the central bank governors of the twelve member states, chaired by the President of the European Commission, Jacques Delors, was asked to propose a new timetable with clear, practical and realistic steps for creating an economic and monetary union.[8] This way of working was derived from the Spaak method.

The Delors report of 1989 set out a plan to introduce the EMU in three stages and it included the creation of institutions like the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), which would become responsible for formulating and implementing monetary policy.[9]

The three stages for the implementation of the EMU were the following:

Stage One: 1 July 1990 to 31 December 1993

[edit]- On 1 July 1990, exchange controls are abolished, thus capital movements are completely liberalised in the European Economic Community.

- The Treaty of Maastricht in 1992 establishes the completion of the EMU as a formal objective and sets a number of economic convergence criteria, concerning the inflation rate, public finances, interest rates and exchange rate stability.

- The treaty enters into force on 1 November 1993.

Stage Two: 1 January 1994 to 31 December 1998

[edit]- The European Monetary Institute is established as the forerunner of the European Central Bank, with the task of strengthening monetary cooperation between the member states and their national banks, as well as supervising ECU banknotes.

- On 16 December 1995, details such as the name of the new currency (the euro) as well as the duration of the transition periods are decided.

- On 16–17 June 1997, the European Council decides at Amsterdam to adopt the Stability and Growth Pact, designed to ensure budgetary discipline after creation of the euro, and a new exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) is set up to provide stability above the euro and the national currencies of countries that haven't yet entered the eurozone.

- On 3 May 1998, at the European Council in Brussels, the 11 initial countries that will participate in the third stage from 1 January 1999 are selected.

- On 1 June 1998, the European Central Bank (ECB) is created, and on 31 December 1998, the conversion rates between the 11 participating national currencies and the euro are established.

Stage Three: 1 January 1999 and continuing

[edit]- From the start of 1999, the euro is now a real currency, and a single monetary policy is introduced under the authority of the ECB. A three-year transition period begins before the introduction of actual euro notes and coins, but legally the national currencies have already ceased to exist.

- On 1 January 2001, Greece joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2002, the euro notes and coins are introduced.

- On 1 January 2007, Slovenia joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2008, Cyprus and Malta join the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2009, Slovakia joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2011, Estonia joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2014, Latvia joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2015, Lithuania joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2023, Croatia joins the third stage of the EMU.

Criticism

[edit]There have been debates as to whether the Eurozone countries constitute an optimum currency area.[10]

There has also been significant doubt if all eurozone states really fulfilled a "high degree of sustainable convergence" as demanded by the Maastricht treaty as condition to join the Euro without getting into financial trouble later on.[citation needed]

Monetary policy inflexibility

[edit]Since membership of the eurozone establishes a single monetary policy and essentially use of a 'foreign currency' for the respective states, they can no longer use an isolated national monetary policy as an economic tool within their central banks. Nor can they issue money to finance any required government deficits or pay interest on government bond sales. All this is effected centrally from the ECB. As a consequence, if member states do not manage their economy in a way that they can show a fiscal discipline (as they were obliged by the Maastricht treaty), the mechanism means a member state could effectively 'run out of money' to finance spending. This is characterized as a sovereign debt crisis where a country is without the possibility of refinancing itself with a sovereign currency. This is what happened to Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Cyprus, and Spain.[11]

Plans for reformed Economic and Monetary Union

[edit]Being of the opinion that the pure austerity course was not able to solve the Euro-crisis, French President François Hollande reopened the debate about a reform of the architecture of the Eurozone. The intensification of work on plans to complete the existing EMU in order to correct its economic errors and social upheavals soon introduced the keyword "genuine" EMU.[12] At the beginning of 2012, a proposed correction of the defective Maastricht currency architecture comprising: introduction of a fiscal capacity of the EU, common debt management and a completely integrated banking union, appeared unlikely to happen.[13] Additionally, there were widespread fears that a process of strengthening the Union's power to intervene in eurozone member states and to impose flexible labour markets and flexible wages, might constitute a serious threat to Social Europe.[14] In the negotiation process, member states advocated different solutions depending on their social and political characteristics, while the result was a broad compromise.[15][16]

First EMU reform plan (2012–2015)

[edit]In December 2012, at the height of the European sovereign debt crisis, which revealed a number of weaknesses in the architecture of the EMU, a report entitled "Towards a genuine Economic and Monetary Union" was issued by the four presidents of the Council, European Commission, ECB and Eurogroup. The report outlined the following roadmap for implementing actions being required to ensure the stability and integrity of the EMU:[17]

| Roadmap[17] | Action plan[17] | Status as of June 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Ensuring fiscal sustainability and breaking the costly link between banks and sovereigns (2012–13) |

Framework for fiscal governance shall be completed through implementation of: Six-Pack, Fiscal Compact, and Two-Pack. | Point fully achieved through entry into force of the Six‑Pack in December 2011, Fiscal Compact in January 2013 and Two‑Pack in May 2013. |

| Establish a framework for systematic Ex Ante Coordination of major economic policy reforms (as per Article 11 of the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance). | A pilot project was conducted in June 2014, which recommended the design of the yet to be developed Ex Ante Coordination (EAC) framework, should be complementary to the instruments already in use as part of the European Semester, and should be based on the principle of "voluntary participation and non-binding outcome". Meaning the end result of an EAC should not be a final dictate, but instead just an early delivered politically approved non-binding "advisory note" put forward to the national parliament, which then can be taken into consideration, as part of their process on improving and finalizing the design of their major economic reform in the making.[18] | |

| Establish European Banking Supervision as a first element of the Banking union of the European Union, and ensure the proposed Capital Requirements Directive and Regulation (CRD‑IV/CRR) will enter into force. | This point was fully achieved, when CRD‑IV/CRR entered into force in July 2013 and European Banking Supervision became operational in November 2014. | |

| Agreement on the harmonisation of national resolution and deposit guarantee frameworks, so that the financial industry across all countries contribute appropriately under the same set of rules. | This point has now been fully achieved, through the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD; Directive 2014/59/EU of 15 May 2014) which established a common harmonized framework for the recovery and resolution of credit institutions and investment firms found to be in danger of failing, and through the Deposit Guarantee Scheme Directive (DGSD; Directive 2014/49/EU of 16 April 2014) which regulates deposit insurance in case of a bank's inability to pay its debts. | |

| Establish a new operational framework under the auspice of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), for conducting "direct bank recapitalization" between the ESM rescue fund and a country-specific systemic bank in critical need, so that the general government of the country in which the beneficiary is situated won't be involved as a guaranteeing debtor on behalf of the bank. This proposed new instrument, would be contrary to the first framework made available by ESM for "bank recapitalizations" (utilized by Spain in 2012–13), which required the general government to step in as a guaranteeing debtor on behalf of its beneficiary banks – with the adverse impact of burdening their gross debt-to-GDP ratio. | ESM made the proposed "direct bank recapitalization" framework operational starting from December 2014, as a new novel ultimate backstop instrument for systemic banks in their recovery/resolution phase, if such banks will be found in need to receive additional recapitalization funds after conducted bail-in by private creditors and regulated payment by the Single Resolution Fund.[19] | |

| Stage 2: Completing the integrated financial framework and promoting sound structural policies (2013–14) |

Complete the Banking union of the European Union, by establishing the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) as a common resolution authority and setting up the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) as an appropriate financial backstop. | SRM was established in January 2015, SRF started working from January 2016. |

| Establish a new "mechanism for stronger coordination, convergence and enforcement of structural policies based on arrangements of a contractual nature between Member States and EU institutions on the policies countries commit to undertake and on their implementation". The envisaged contractual arrangements "could be supported with temporary, targeted and flexible financial support", although if such support is granted it "should be treated separately from the multiannual financial framework". | Status unknown. (mentioned as part of stage 2 in the updated 2015 reform plan) | |

| Stage 3: Improving the resilience of EMU through the creation of a shock-absorption function at the central level (2015 and later) |

"Establish a well-defined and limited fiscal capacity to improve the absorption of country-specific economic shocks, through an insurance system set up at the central level." Such fiscal capacity would reinforce the resilience of the eurozone, and is envisaged to be complementary to the "contractual arrangements" created in stage 2. The idea is to establish it as a built-in incentives-based system, so that eurozone Member States eligible for participation in this centralized asymmetrically working "economic shock-absorption function" are encouraged to continue implementing sound fiscal policy and structural reforms in accordance with their "contractual obligations", making these two new instruments intrinsically linked and mutually reinforcing. | Status unknown. (mentioned as part of stage 2 in the updated 2015 reform plan) |

| Establish an increasing degree of "common decision-making on national budgets" and an "enhanced coordination of economic policies". A subject to "enhanced coordination", could in example be the specific taxation and employment policies implemented by the National Job Plan of each Member State (published as part of their annual National Reform Programme). | Status unknown. (mentioned as part of stage 2 in the updated 2015 reform plan) |

Second EMU reform plan (2015–2025): The Five Presidents' Report

[edit]In June 2015, a follow-up report entitled "Completing Europe's Economic and Monetary Union" (often referred to as the "Five Presidents Report") was issued by the presidents of the Council, European Commission, ECB, Eurogroup and European Parliament. The report outlined a roadmap for further deepening of the EMU, meant to ensure a smooth functioning of the currency union and to allow the member states to be better prepared for adjusting to global challenges:[20]

- Stage 1 (July 2015 – June 2017): The EMU should be made more resilient by building on existing instruments and making the best possible use of the existing Treaties. In other words, "deepening by doing". This first stage comprise implementation of the following eleven working points.

- Deepening the Economic Union by ensuring a new boost to convergence, jobs and growth across the entire eurozone. This shall be achieved by:

- Creation of a eurozone system of Competitiveness Authorities:

Each eurozone state shall (like Belgium and Netherlands already did) create an independent national body in charge of tracking its competitiveness performance and policies for improving competitiveness. The proposed "Eurozone system of Competitiveness Authorities" would bring together these national bodies and the Commission, which on an annual basis would coordinate the "recommendation for actions" being issued by the national Competitiveness Authorities. - Strengthened implementation of the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure:

(A) Its corrective arm (Excessive Imbalance Procedure) is currently only triggered if excessive imbalances are identified while the state subsequently also fails to deliver a National Reform Programme sufficiently addressing the found imbalances, and the reform implementation surveillance reports published for states with excessive imbalance but without EIP only work as a non-legal peer-pressure instrument.[21] In the future, the EIP should be triggered as soon as excessive imbalances are identified, so that the Commission more forcefully within this legal framework can require implementation of structural reforms - followed by a period of extended reform implementation surveillance in which continued incompliance can be sanctioned.

(B) The Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure should also better capture imbalances (external deficits) for the eurozone as a whole - not just for each individual country, and also require implementation of reforms in countries accumulating large and sustained current account surpluses (if caused by insufficient domestic demand or low growth potential). - Greater focus on employment and social performance in the European Semester:

There is no "one-size-fits-all" standard template to follow, meaning that no harmonized specific minimum standards are envisaged to be set up as compliance requirements in this field. But as the challenges often are similar across Member States, their performance and progress on the following indicators could be monitored in the future as part of the annual European Semester: (A) Getting more people of all ages into work; (B) Striking the right balance between flexible and secure labour contracts; (C) Avoiding the divide between "labor market insiders" with high protection and wages and "labor market outsiders"; (D) Shifting taxes away from labour; (E) Delivering tailored support for the unemployed to re-enter the labour market; (F) Improving education and lifelong learning; (G) Ensure that every citizen has access to an adequate education; (H) Ensure that an effective social protection system and "social protection floor" are in place to protect the most vulnerable in society; (I) Implementation of major reforms to ensure pension and health systems can continue functioning in a socially just way while coping with the rising economic expenditure pressures stemming from the rapidly ageing populations in Europe - in example by aligning the retirement age with life expectancy. - Stronger coordination of economic policies within a revamped European Semester:

(A) The Country-Specific Recommendations which are already in place as part of the European Semester, need to focus more on "priority reforms", and shall be more concrete in regards of their expected outcome and time-frame for delivery (while still granting the Member State political maneuver room on how the exact measures shall be designed and implemented).

(B) Periodic reporting on national reform implementation, regular peer reviews or a "comply-or-explain" approach should be used more systematically to hold the Member States accountable for the delivery of their National Reform Programme commitments. The Eurogroup could also play a coordinating role in cross-examining performance, with increased focus on benchmarking and pursuing best practices within the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP) framework.

(C) The annual cycle of the European Semester should be supplemented by a stronger multi-annual approach in line with the renewed convergence process. - Completing and fully exploiting the Single Market by creating an Energy Union and Digital Market Union.

- Creation of a eurozone system of Competitiveness Authorities:

- Complete construction of the Banking union of the European Union. This shall be achieved by:

- Setting up a bridge financing mechanism for the Single Resolution Fund (SRF):

Building up SRF with sufficient funds, is an ongoing process to be conducted through eight years of annual contributions made by the financial sector, as regulated by the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive. The bridge financing mechanism is envisaged to be made available as a supplementing instrument, in order to make SRF capable straight from the first day it becomes operational (1 January 2016) to conduct potential large scale immediate transfers for resolution of financial institutions in critical need. The mechanism will only exist temporarily, until a certain level of funds have been collected by SRF. - Implementing concrete steps towards the common backstop to the SRF:

An ultimate common backstop should also be established to the SRF, for the purpose of handling rare severe crisis events featuring a total amount of resolution costs beyond the capacity of the funds held by SRF. This could be done through the issue of an ESM financial credit line to SRF, with any potential draws from this extra standby arrangement being conditioned on simultaneous implementation of extra ex-post levies on the financial industry, to ensure full repayment of the drawn funds to ESM over a medium-term horizon. - Agreeing on a common European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS):

A new common deposit insurance would be less vulnerable than the current national deposit guarantee schemes, towards eruption of local shocks (in particular when both the sovereign and its national banking sector is perceived by the market to be in a fragile situation). It would also carry less risk for needing injection of additional public money to service its payment of deposit guarantees in the event of severe crisis, as failing risks would be spread more widely across all member states while its private sector funds would be raised over a much larger pool of financial institutions. EDIS would just like the national deposit guarantee schemes be privately funded through ex ante risk-based fees paid by all the participating banks in the Member States, and be devised in a way that would prevent moral hazard. Establishment of a fully-fledged EDIS will take time. A possible option would be to devise the EDIS as a re-insurance system at the European level for the national deposit guarantee schemes. - Improving the effectiveness of the instrument for direct bank recapitalisation in the European Stability Mechanism:

The ESM instrument for direct bank recapitalisation was launched in December 2014,[19] but should soon be reviewed for the purpose of loosening its restrictive eligibility criteria (currently it only applies for systemically important banks of countries unable to function as alternative backstop themselves without endangering their fiscal stability), while there should be made no change to the current requirement for a prior resolution bail-in by private creditors and regulated SRF payment for resolution costs first to be conducted before the instrument becomes accessible.

- Setting up a bridge financing mechanism for the Single Resolution Fund (SRF):

- Launch a new Capital Markets Union (CMU):

- The European Commission has published a green paper describing how they envisage to build a new Capital Markets Union (CMU),[22] and will publish a more concrete action plan for how to achieve it in September 2015. The CMU is envisaged to include all 28 EU Members and to be fully build by 2019. Its construction will:

- (A) Improve access to financing for all businesses across Europe and investment projects, in particular start-ups, SMEs and long-term projects.

- (B) Increase and diversify the sources of funding from investors in the EU and all over the world, so that companies (including SMEs) in addition to the already available bank credit lending also can tap capital markets through alternative funding sources that better suits them.

- (C) Make the capital markets work more effectively by connecting investors and those who need funding more efficiently, both within Member States and cross-border.

- (D) Make the capital markets more shock resilient by pooling cross-border private risk-sharing through a deepening integration of bond and equity markets, hereby also protecting it better against the risk for systemic shocks in the national financial sector.

- The establishment of the CMU, is envisaged at the same time to require a strengthening of the available tools to manage systemic risks of financial players prudently (macro-prudential toolkit), and a strengthening of the supervisory framework for financial actors to ensure their solidity and that they have sufficient risk management structures in place (ultimately leading to the launch of a new single European capital markets supervisor). A harmonized taxation scheme for capital market activities, could also play an important role in terms of providing a neutral treatment for different but comparable activities and investments across jurisdictions. A genuine CMU is envisaged also to require update of EU legislation in the following four areas: (A) Simplification of prospectus requirements; (B) Reviving the EU market for high quality securitisation; (C) Greater harmonisation of accounting and auditing practices; (D) Addressing the most important bottlenecks preventing the integration of capital markets in areas like insolvency law, company law, property rights and the legal enforceability of cross-border claims.

- The European Commission has published a green paper describing how they envisage to build a new Capital Markets Union (CMU),[22] and will publish a more concrete action plan for how to achieve it in September 2015. The CMU is envisaged to include all 28 EU Members and to be fully build by 2019. Its construction will:

- Reinforce the European Systemic Risk Board, so that it becomes capable of detecting risks to the financial sector as a whole.

- Launch a new advisory European Fiscal Board:

- This new independent advisory entity would coordinate and complement the work of the already established independent national fiscal advisory councils. The board would also provide a public and independent assessment, at European level, of how budgets – and their execution – perform against the economic objectives and recommendations set out in the EU fiscal framework. Its issued opinions and advice should feed into the decisions taken by the Commission in the context of the European Semester.

- Revamp the European Semester by reorganizing it to follow two consecutive stages. The first stage (stretching from November to February) shall be devoted to the eurozone as a whole, and the second stage (stretching from March to July) then subsequently feature a discussion of country specific issues.

- Strengthen parliamentary control as part of the European Semester. This shall be achieved by:

- Plenary debate at the European Parliament first on the Annual Growth Survey and then on the Country-Specific Recommendations.

- More systematic interactions between Commissioners and national Parliaments on Country-Specific Recommendations and on national budgets.

- More systematic consultation by governments of national Parliaments and social partners before submitting National Reform and Stability Programmes.

- Increase the level of cooperation between the European Parliament and national Parliaments.

- Reinforce the steer of the Eurogroup:

- As the Eurogroup will step up its involvement and steering role in the revamped European Semester, a reinforcement of its presidency and provided means at its disposal, may be required.

- Take steps towards a consolidated external representation of the eurozone:

- The EU and the eurozone are still not represented as one voice in the international financial institutions (i.e. in IMF), which mean Europeans speak with a fragmented voice, leading to the EU punching below its political and economic weight. Although the building of consolidated external representation is desirable, it is envisaged to be a gradual process, with only the first steps to be taken in stage 1.

- Integrate intergovernmental agreements into the framework of EU law. This includes the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance, the relevant parts of the Euro Plus Pact; and the Intergovernmental Agreement on the Single Resolution Fund.

- Stage 2: The achievements of the first stage would be consolidated. On basis of consultation with an expert group, the European Commission will publish a white paper in Spring 2017, which will conduct an assessment of progress made in Stage 1, and outline in more details the next steps and measures needed for completion of the EMU in Stage 2. This second stage is currently envisaged to comprise:

- The intergovernmental European Stability Mechanism should be moved into becoming part of the EU treaty law applying automatically for all eurozone member states (something which is possible to do within existing paragraphs of the current EU treaty), in order to simplify and institutionalize its governance.

- More far-reaching measures (i.e. commonly agreed "convergence benchmark standards" of a more binding legal nature, and a treasury for the eurozone), could also be agreed to complete the EMU's economic and institutional architecture, for the purpose of making the convergence process more binding.

- Significant progress towards these new common "convergence benchmark standards" (focusing primarily on labour markets, competitiveness, business environment, public administrations, and certain aspects of tax policy like i.e. the corporate tax base) – and a continued adherence to them once they are reached – would need to be verified by regular monitoring and would be among the conditions for each eurozone Member State to meet in order to become eligible for participation in a new fiscal capacity referred to as the "economic shock absorption mechanism", which will be established for the eurozone as a last element of this second stage. The fundamental idea behind the "economic shock absorption mechanism", is that its conditional shock absorbing transfers shall be triggered long before there is a need for ESM to offer the country a conditional macroeconomic crisis support programme, but that the mechanism at the same time never shall result in permanent annual transfers - or income equalizing transfers - between countries. A first building block of this "economic shock absorption mechanism", could perhaps be establishment of a permanent version of the European Fund for Strategic Investments, in which the tap by a country into the identified pool of financing sources and future strategic investment projects could be timed to occur upon the periodic eruption of downturns/shocks in its economic business cycle.

- Another important pre-condition for the launch of the "economic shock absorption mechanism", is expected to be, that the eurozone first establish an increasing degree of "common decision-making on national budgets" and an "enhanced coordination of economic policies" (i.e. of the specific taxation and employment policies implemented by the National Job Plan of each Member State - which is published as part of their annual National Reform Programme).

- Stage 3 (by 2025): Reaching the final stage of "a deep and genuine EMU", by also considering the prospects of potential EU treaty changes.

All of the above three stages are envisaged to bring further progress on all four dimensions of the EMU:[20]

- Economic union: Focusing on convergence, prosperity, and social cohesion.

- Financial union: Completing the Banking union of the European Union and constructing a capital markets union.

- Fiscal union: Ensuring sound and integrated fiscal policies

- Political Union: Enhancing democratic accountability, legitimacy and institutional strengthening of the EMU.

Primary sources

[edit]The Historical Archives of the European Central Bank published the minutes, reports and transcripts of the Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union ('Delors Committee') in March 2020.[23]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Simonazzi, Annamaria; Vianello, Fernando (2000), "Italy towards European Monetary Union (and domestic socio-economic disunion)", in Moss, Bernard H.; Michie, Jonathan (eds.), The single European currency in national perspective: a community in crisis?, Basingstoke: Macmillan, ISBN 9780333792933.

- Hacker, Björn (2013). On the way to a fiscal or a stability union? The plans for a "genuine" economic and monetary union (PDF). Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Internat. Policy Analysis. ISBN 9783864987465.

- Miles, Lee; Doherty, Gabriel (March 2005). "The United Kingdom: a cautious euro-outsider". Journal of European Integration. 27 (1): 89–109. doi:10.1080/07036330400030064. S2CID 154539276.

- Howarth, David (March 2007). "The domestic politics of British policy on the Euro". Journal of European Integration. 29 (1): 47–68. doi:10.1080/07036330601144409. S2CID 153678875.

References

[edit]- ^ Bank, European Central (10 July 2020). "Economic and Monetary Union".

- ^ "What is the Economic and Monetary Union? (EMU)".

- ^ Bolton, Sally (10 December 2001). "A history of currency unions". guardian. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

France persuaded Belgium, Italy, Switzerland and Greece

- ^ Pollard, John F. (2005). Money and the Rise of the Modern Papacy: Financing the Vatican, 1850–1950. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-521-81204-7.

- ^ Link

- ^ Harold James (2020). "The BIS and the European Monetary Experiment". In Claudio Borio; Stijn Claessens; Piet Clement; Robert McCauley; Hyun Song Shin (eds.). Promoting Global Monetary and Financial Stability: The Bank for International Settlements after Bretton Woods, 1973-2020. Cambridge University Press. p. 13.

- ^ Barre Report

- ^ Verdun A., The role of the Delors Committee in the creation of EMU: an epistemic community?, Journal of European Public Policy, Volume 6, Number 2, 1 June 1999, pp. 308–328(21)

- ^ Delors Report

- ^ "As Euro Nears 10, Cracks Emerge in Fiscal Union" (The New York Times, 1 May 2008)

- ^ "Project Syndicate-Martin Feldstein-The French Don't Get It-December 2011". Project-syndicate.org. 28 December 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Hacker, Björn (2013): On the Way to a Fiscal or a Stability Union? The Plans for a »Genuine« Economic and Monetary Union, FES, online at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/10400.pdf

- ^ Busch, Klaus (April 2012): Is the Euro Failing? Structural Problems and Policy Failures Bringing Europe to the Brink, FES, online at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/09034.pdf

- ^ Janssen, Ronald (2013): A Social Dimension for a Genuine Economic Union, SEJ, online at: http://www.social-europe.eu/2013/03/a-social-dimension-for-a-genuine-economic-union/ Archived 19 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Târlea, Silvana; Bailer, Stephanie; Degner, Hanno; Dellmuth, Lisa; Leuffen, Dirk; Lundgren, Magnus; Tallberg, Jonas; Wasserfallen, Fabio (2019). "Explaining governmental preferences on economic and monetary union reform". European Union Politics. 20 (1): 24–44. doi:10.1177/1465116518814336. S2CID 158507389.

- ^ Lundgren, Magnus; Bailer, Stephanie; Dellmuth, Lisa; Tallberg, Jonas; Târlea, Silvana (2019). "Bargaining success in the reform of the Eurozone". European Union Politics. 20 (1): 65–88. doi:10.1177/1465116518811073. S2CID 85459046.

- ^ a b c "Towards a genuine Economic and Monetary Union". European Commission. 5 December 2012.

- ^ "Ex ante coordination of major economic reform plans –report on the pilot exercise". Council of the European Union (Economic and Financial Committee). 17 June 2014.

- ^ a b "ESM direct bank recapitalisation instrument adopted". ESM. 8 December 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Completing Europe's Economic and Monetary Union: Report by Jean-Claude Juncker in close cooperation with Donald Tusk, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Mario Draghi and Martin Schulz". European Commission. 21 June 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "Economic governance review: Report on the application of Regulations (EU) n° 1173/2011, 1174/2011, 1175/2011, 1176/2011, 1177/2011, 472/2013 and 473/2013" (PDF). European Commission. 28 November 2014.

- ^ "Green Paper: Building a Capital Markets Union". European Commission. 18 February 2015.

- ^ Bank, European Central (20 March 2020). "Delors Committee". European Central Bank.

External links

[edit]- EMU: A Historical Documentation (European Commission)

- The euro (European Commission Economic and Financial Affairs)

- European integration process: 1969–1979 Crises and revival: Economic and Monetary Union cooperation subject file by the CVCE (Centre of European Studies)

- Completing Europe's Economic and Monetary Union: Five presidents' report (EC, EP, ECB, Eurogroup and Council) Archived 11 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Objectives

The Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) constitutes the framework for integrating the economies of European Union member states through coordinated economic policies, a unified monetary policy managed by the European Central Bank (ECB), and the adoption of the euro as a common currency by participating countries.[1] Launched via the Treaty on European Union, signed on 7 February 1992 in Maastricht and effective from 1 November 1993, EMU builds on the single market by enforcing convergence criteria for fiscal discipline and monetary alignment.[1] [3] All EU member states engage in the economic coordination aspect, while those in the euro area—currently 20 countries—implement the full monetary union.[9] The core objectives of EMU, as outlined in the founding treaties, encompass maintaining price stability as the paramount goal of monetary policy, alongside fostering sustainable and non-inflationary growth, high employment, and convergence of economic performances.[1] [10] The ECB's mandate prioritizes price stability, targeting a medium-term inflation rate of around but below 2%, to support broader aims of economic stability and balanced growth across the Union. Fiscal policy coordination, including limits on government deficits (3% of GDP) and debt (60% of GDP), aims to prevent excessive imbalances that could undermine these goals.[11] EMU's design reflects an intent to enhance the efficiency, scale, and resilience of EU economies by reducing transaction costs from currency fluctuations and promoting trade and investment through policy harmonization.[1] While serving as a means rather than an end, it seeks to deliver stronger, more inclusive growth while addressing challenges like asymmetric shocks via mechanisms such as the Stability and Growth Pact.[11] Empirical assessments indicate that the euro has facilitated intra-euro area trade increases of 5-15% post-adoption, though debates persist on whether full benefits require deeper fiscal integration.Key Institutions and Governance

The governance of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) separates centralized monetary policy from decentralized fiscal and economic policies coordinated among member states. Monetary authority is vested in supranational bodies to ensure uniform implementation across the euro area, while economic surveillance relies on multilateral frameworks to enforce fiscal discipline without full fiscal transfer mechanisms.[1][12] The European Central Bank (ECB) serves as the cornerstone institution for monetary policy, tasked with maintaining price stability—defined as a year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) of around 2% over the medium term—throughout the euro area. Established on June 1, 1998, and commencing operations on January 1, 1999, the ECB's primary objective excludes promoting employment or growth directly, prioritizing inflation control via instruments such as key interest rates, open market operations, and reserve requirements. Its independence from national governments and EU institutions is mandated by Article 130 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), prohibiting instructions from external bodies and limiting government financing. The ECB's Governing Council, comprising the six-member Executive Board and the governors of the 20 national central banks (NCBs) of euro area states, convenes at least ten times annually to formulate policy; decisions require a simple majority, with the President casting a tie-breaking vote.[12][13] The European System of Central Banks (ESCB) integrates the ECB with the NCBs of all 27 EU Member States, facilitating monetary policy execution, foreign reserve management, and payment system oversight, even for non-euro members. Within the euro area, the Eurosystem—the ECB plus euro area NCBs—handles operational implementation, including liquidity provision and banknote issuance; NCBs retain roles in supervision and statistics but cede independent monetary decision-making to the ECB. This structure, formalized under Articles 127–132 TFEU, ensures policy consistency while preserving national operational autonomy.[14][15] On the economic side, the Eurogroup provides informal coordination among euro area finance ministers, the European Commissioner for Economy, and the ECB President, focusing on fiscal policies, competitiveness, and crisis response without formal decision-making powers. Comprising representatives from the 20 euro-using states, it meets monthly ahead of the Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) to align positions on EMU-specific issues, such as financial assistance via the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The Eurogroup President, elected by members for a 2.5-year renewable term—currently held by Paschal Donohoe since 2020—chairs proceedings and represents the group externally.[16] Supporting bodies include the Economic and Financial Committee (EFC), which advises on policy coordination and monitors fiscal risks, and the European Commission, which conducts annual surveillance under the Stability and Growth Pact, issuing recommendations for excessive deficit procedures. The European Council defines strategic orientations, while ECOFIN endorses binding decisions on sanctions or reforms. This hybrid governance has enabled crisis interventions, such as the ECB's €2.6 trillion asset purchase programs from 2015–2022, but empirical data indicate persistent challenges in asymmetric shocks due to absent fiscal union elements like common debt issuance.[1][17]Legal Framework

Convergence Criteria

The convergence criteria, formalized in Article 140 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (formerly Article 109j of the Maastricht Treaty), require prospective euro area members to demonstrate economic alignment through four primary macroeconomic benchmarks, supplemented by legal compatibility assessments. These criteria aim to ensure price stability, fiscal sustainability, exchange rate discipline, and interest rate convergence prior to adopting the euro, with evaluations conducted biennially via joint European Commission and European Central Bank (ECB) convergence reports.[18][19] The price stability criterion mandates that a member state's 12-month average harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP) inflation rate must not exceed by more than 1.5 percentage points the average inflation rate of the three best-performing EU member states in terms of price stability over the reference period. This threshold, derived from Protocol No. 13 of the Maastricht Treaty, seeks to prevent inflationary divergences that could undermine monetary union cohesion.[18][19] Fiscal sustainability is assessed through two sub-criteria: the general government budgetary deficit must not exceed 3% of gross domestic product (GDP) at market prices, unless justified by extraordinary circumstances or in the process of correction, and public debt must not exceed 60% of GDP or must be diminishing sufficiently and approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace. These limits, also from Protocol No. 13, enforce budgetary discipline to avoid free-rider problems in a shared currency area without fiscal transfer mechanisms.[18][19] Exchange rate stability requires participation in the Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II) for at least two years without devaluation of the central rate against the euro on the member's own initiative and in the absence of severe tensions. This criterion verifies the durability of nominal exchange rate pegs, drawing on the European Monetary System's legacy to mitigate speculative pressures post-adoption.[18][19] Long-term interest rate convergence stipulates that the average nominal long-term interest rate (over 10 years) must not exceed by more than 2 percentage points the average of the three best-performing member states in terms of price stability. This measures market perceptions of fiscal and monetary credibility, independent of short-term rates influenced by central bank policies.[18][19] Additionally, legal convergence demands that national legislation be compatible with the European Central Bank's statutes and the European System of Central Banks, enabling effective monetary policy transmission and independence from political interference. The Council, based on Commission and ECB reports, decides on fulfillment, as occurred for initial entrants like Greece in 2001 despite later revelations of data inaccuracies in deficit reporting.[19][20]| Criterion | Reference Value/Requirement |

|---|---|

| Price stability | HICP inflation ≤ average of three best-performing MS + 1.5 pp |

| Government deficit | ≤ 3% of GDP |

| Government debt | ≤ 60% of GDP or approaching satisfactorily |

| Exchange rate | ≥ 2 years in ERM II without devaluation or severe tensions |

| Long-term interest rate | ≤ average of three best-performing MS (in price stability) + 2 pp |

Stability and Growth Pact

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) is a reinforced framework of fiscal rules within the European Union's Economic and Monetary Union, designed to promote budgetary discipline, prevent excessive government deficits, and facilitate coordination of national fiscal policies to support overall economic stability.[22] It builds on the convergence criteria established by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, specifying reference values of a budget deficit not exceeding 3% of GDP and public debt not exceeding 60% of GDP, or diminishing sufficiently toward that level if above it.[23] These thresholds aim to safeguard the euro area's monetary policy by limiting risks of fiscal imbalances spilling over into inflation or sovereign debt crises, reflecting a causal link between unchecked public borrowing and reduced central bank independence.[24] The SGP comprises a preventive arm and a corrective arm. Under the preventive arm, euro area member states submit annual Stability Programmes, while non-euro EU countries submit Convergence Programmes, outlining medium-term budgetary objectives and projections; the European Commission assesses compliance and issues recommendations via the European Semester process.[22] The corrective arm activates the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) when a member state breaches the 3% deficit threshold or fails to address high debt levels, requiring corrective action plans that may include deposit requirements or fines up to 0.5% of GDP if deadlines are missed, though enforcement has historically been inconsistent.[25] As of January 2025, EDPs remain active for countries including Belgium, France, Italy, Malta, and Poland, with Council recommendations urging deficit reductions.[26] Adopted through a European Council resolution on 17 June 1997 and two Council regulations on 7 July 1997 (Nos. 1466/97 and 1467/97), the SGP operationalized Maastricht's fiscal provisions amid concerns that monetary union without binding rules could lead to moral hazard, where high-deficit states free-ride on low-deficit ones' prudence.[24] Early implementation faltered when France and Germany exceeded the 3% deficit limit in 2003, prompting the Ecofin Council to suspend EDP steps against them on 25 November 2003, effectively blocking fines and eroding pact credibility; this decision, criticized for favoring politically influential states, led to a 2005 reform introducing more flexibility for economic downturns but weakening automaticity.[27] Subsequent reforms addressed these shortcomings: the 2011 "Six Pack" regulations enhanced enforcement with reverse qualified majority voting for Commission recommendations and introduced a macroeconomic imbalance procedure; the 2013 "Two Pack" added pre-emptive oversight for euro states' budgets.[24] The SGP was suspended from 2020 to 2023 under a general escape clause for COVID-19 response, accumulating deficits that pushed EU debt to 82.9% of GDP by 2023.[22] A 2024 reform, agreed via Regulation 2024/1233, mandates net expenditure paths over four-to-seven-year adjustment periods, exempting certain investments while requiring high-debt countries (above 90% GDP) to cut debt by 1% annually, aiming for sustainability but raising concerns over complexity and potential for renewed laxity.[28] Empirical evidence shows the pre-2011 SGP reduced deficits by about 0.6-1% of GDP on average but failed to curb violations by large economies, underscoring enforcement's dependence on political will rather than rules alone.[29]Historical Development

Early Developments and Delors Report

The push for economic and monetary union (EMU) in Europe gained momentum in the late 1970s and 1980s amid efforts to stabilize exchange rates following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 and recurrent currency crises within the European Economic Community (EEC).[4] The European Monetary System (EMS), established in 1979, introduced the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) to limit fluctuations between member currencies via a grid of bilateral central rates, fostering greater monetary coordination among participating EEC countries.[4] By the mid-1980s, the success of the ERM in reducing volatility—evidenced by narrower bands of fluctuation compared to earlier mechanisms like the 1972 "snake"—encouraged ambitions for a single currency, though divergent national economic policies and inflation rates posed persistent challenges.[4] The Single European Act of 1986 further advanced integration by committing to the completion of the internal market by 1992, indirectly supporting monetary convergence through enhanced economic interdependence.[4] In June 1988, the European Council, meeting in Hanover, tasked a committee chaired by European Commission President Jacques Delors with studying the feasibility of EMU, building on prior initiatives like the 1970 Werner Report that had proposed staged monetary union but faltered due to the 1973 oil crisis and ensuing divergences.[30] The Delors Committee, comprising central bank governors and Commission representatives, analyzed existing monetary arrangements and concluded that EMU required parallel advances in economic policy coordination to mitigate risks from asymmetric shocks.[30] The committee emphasized that monetary union without fiscal and structural alignment could exacerbate imbalances, drawing on empirical evidence from EMS experiences where high-inflation countries like Italy and Greece faced devaluation pressures despite ERM commitments.[31] The committee's report, titled Economic and Monetary Union in the European Community and submitted on April 17, 1989, outlined a three-stage roadmap to achieve EMU by the mid-1990s.[32] Stage One focused on irrevocably fixing exchange rates through full capital liberalization and intensified policy dialogue, without requiring treaty amendments initially.[4] Stage Two envisioned creating a European Monetary Institute to oversee convergence and prepare for a central bank, enforcing stricter criteria on inflation, deficits, and interest rates.[4] Stage Three proposed the launch of a single currency managed by a European Central Bank, with binding rules for economic policy to ensure stability amid relinquished national monetary sovereignty.[4] The report stressed causal links between monetary credibility and low inflation, arguing that a federal-like structure was essential to prevent free-riding by high-debt members.[31] The European Council endorsed the Delors Report at its June 1989 Madrid summit, deciding to commence Stage One on July 1, 1990, and initiating intergovernmental negotiations that culminated in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992.[4] This framework prioritized gradualism to build institutional trust, though skeptics noted risks of incomplete economic union leading to future crises, as later evidenced by divergences in the 2010s.[33] The report's emphasis on convergence criteria—such as public debt below 60% of GDP and inflation within 1.5% of the best performers—laid the empirical foundation for assessing member readiness, influencing subsequent assessments of fiscal discipline.[32]Stage One: 1990-1993

Stage One of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) commenced on 1 July 1990, following the European Council's decision at the Madrid Summit in June 1989 to implement the first phase outlined in the 1989 Delors Committee Report, which proposed a gradual transition to a single currency through enhanced policy coordination.[4] This stage, lasting until 31 December 1993, focused on foundational measures to foster economic integration without yet establishing a common monetary policy, emphasizing national autonomy in monetary affairs alongside multilateral consultations.[3] The primary objective was to promote convergence by addressing disparities in economic performance, particularly inflation and fiscal balances, while avoiding excessive government deficits through voluntary guidelines rather than binding rules.[4] A cornerstone measure was the full liberalization of capital movements across the then-12 European Community (EC) member states, building on the 1986 Single European Act's directive that required removal of restrictions by 1990, with transitional derogations for countries like Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain extended until the end of 1992 but largely met earlier.[4] This eliminated barriers to cross-border financial flows, enabling freer allocation of savings and investments, and was complemented by the free use of the European Currency Unit (ECU) as a unit of account.[4] Concurrently, the Committee of Governors of the Central Banks, strengthened by a 12 March 1990 Council decision, intensified cooperation on monetary policy to safeguard price stability and prepare for deeper integration, including regular assessments of exchange rate mechanisms within the European Monetary System (EMS).[4] This period also laid institutional groundwork for subsequent stages, culminating in the negotiation and signing of the Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty) on 7 February 1992, which formalized the three-stage EMU timeline, introduced convergence criteria for later phases, and entered into force on 1 November 1993, bridging Stage One to the creation of the European Monetary Institute in Stage Two.[4] Despite these advances, challenges persisted, including EMS crises in 1992–1993 triggered by speculative pressures on currencies like the pound sterling and Italian lira, which led to devaluations and temporary suspensions, underscoring the limits of fixed exchange rates without fiscal transfers or full monetary union.[4] Overall, Stage One advanced economic policy dialogue but highlighted uneven convergence, with average EC inflation falling from around 5% in 1990 to under 3% by 1993, though fiscal deficits varied widely.[4]Stage Two: 1994-1998

Stage Two of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) began on 1 January 1994, coinciding with the entry into force of the Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty) and marked by the establishment of the European Monetary Institute (EMI) as the precursor to the European Central Bank (ECB).[4][34] The EMI, headquartered in the Eurotower in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, was mandated to strengthen coordination of monetary policies among national central banks, promote the convergence of economic policies, and undertake technical preparations for the irrevocable fixing of exchange rates and the conduct of a single monetary policy in Stage Three.[35][36] Headed by President Alexandre Lamfalussy from 1994 to 1997, the EMI lacked independent monetary policy authority but advised member states on achieving sustainable convergence, emphasizing structural reforms to underpin price stability beyond mere nominal criteria compliance.[37][38] A core function of the EMI involved monitoring adherence to the Maastricht convergence criteria, which required inflation rates to remain within 1.5 percentage points of the three best-performing EU member states, budget deficits limited to 3% of GDP, public debt not exceeding 60% of GDP (or diminishing sufficiently toward that threshold), participation in the exchange rate mechanism (ERM) of the European Monetary System without devaluation for at least two years, and long-term nominal interest rates no more than 2 percentage points above the three lowest-inflation states.[38][39] The EMI's first Annual Report, published in April 1995, assessed progress across the then-15 EU member states (following Austria, Finland, and Sweden's accession on 1 January 1995), noting uneven convergence: for instance, while average EU inflation had fallen to around 2.5% by late 1994 from over 5% in the early 1990s, high-debt countries like Italy and Greece faced challenges in reducing deficits below 3% of GDP amid fiscal consolidation efforts.[39] Subsequent reports, such as the November 1995 Progress Towards Convergence, stressed that durable convergence necessitated improvements in labor markets, public expenditure control, and wage moderation to avoid reliance on temporary exchange rate pegs.[38][40] The stage also enforced prohibitions under the Maastricht Treaty against central bank overdraft or credit facilities to public authorities (monetary financing ban) and against privileged access by public entities to financial markets, aiming to insulate monetary policy from fiscal pressures and encourage market discipline on sovereign borrowing.[4][40] Preparatory technical work advanced on harmonizing central bank accounting practices, developing common monetary policy instruments like open market operations, and designing the ECB's future governance structure, including the statutes for the ECB and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB).[35] In December 1995, the European Council in Madrid confirmed "euro" as the single currency's name and outlined a transitional period for its physical introduction, further solidifying logistical planning.[3] By the stage's end on 31 December 1998, the EMI had facilitated greater policy dialogue through regular consultations with national central banks and produced a final Convergence Report in 1998, evaluating legal compatibility with ESCB independence and economic indicators across member states.[41] This assessment, alongside a parallel report from the European Commission, informed the European Council's decision on 3 May 1998 to proceed to Stage Three on 1 January 1999, with eleven countries (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain) deemed to satisfy the criteria, while Greece qualified later in 2000 and others like the United Kingdom opted out.[42][34] Despite progress, the EMI highlighted risks of asymmetric shocks in the absence of fiscal transfers, underscoring the need for national-level adjustments to maintain convergence post-transition.[38]Stage Three: 1999-Present and Euro Launch

Stage Three of the Economic and Monetary Union began on 1 January 1999, with the irrevocable fixing of participation states' bilateral exchange rates to one another at rates predefined in terms of the euro.[4] This marked the operational launch of the euro as an electronic and accounting currency across the initial eleven member states: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain.[43] The European Central Bank (ECB) assumed sole responsibility for monetary policy in the euro area from that date, replacing national central banks' independent conduct of policy with a unified framework aimed at maintaining price stability.[44] The euro's introduction as book money facilitated cross-border transactions without physical notes or coins, with national currencies remaining in parallel use for cash dealings during a transitional period.[43] On 1 January 2002, euro banknotes and coins entered circulation across the euro area, initiating a six-week dual currency phase that concluded on 28 February 2002, after which remaining national notes and coins were demonetized.[45] This cash changeover involved logistical coordination among national authorities and the ECB, processing over 15 billion euro banknotes and 50 billion coins for distribution.[43] Greece joined the euro area on 1 January 2001, becoming the twelfth member after convergence assessments confirmed compliance with the Maastricht criteria, though subsequent revisions revealed initial data discrepancies in deficit reporting.[45] Further enlargements occurred as additional EU states met the necessary economic convergence thresholds, expanding the euro area to twenty members by 2023.[34]| Country | Adoption Date |

|---|---|

| Greece | 1 January 2001 |

| Slovenia | 1 January 2007 |

| Cyprus | 1 January 2008 |

| Malta | 1 January 2008 |

| Slovakia | 1 January 2009 |

| Estonia | 1 January 2011 |

| Latvia | 1 January 2014 |

| Lithuania | 1 January 2015 |

| Croatia | 1 January 2023 |