Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fire arrow

View on Wikipedia

Fire arrows were one of the earliest forms of weaponized gunpowder, being used from the 9th century onward. Not to be confused with earlier incendiary arrow projectiles, the fire arrow was a gunpowder weapon which receives its name from the translated Chinese term huǒjiàn (火箭), which literally means fire arrow. In China, a 'fire arrow' referred to a gunpowder projectile consisting of a bag of incendiary gunpowder attached to the shaft of an arrow. Fire arrows are the predecessors of fire lances, the first firearm.[1]

Later rockets utilizing gunpowder were used to provide arrows with propulsive force and the term fire arrow became synonymous with rockets in the Chinese language. In other languages such as Sanskrit, 'fire arrow' (agni astra) underwent a different semantic shift and became synonymous with 'cannon'.[2]

Design

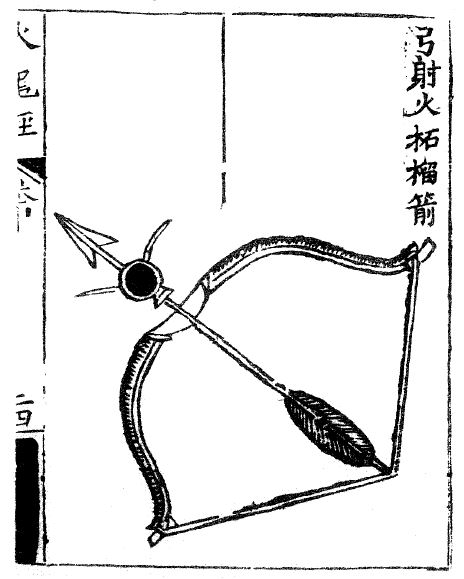

[edit]Although the fire arrow is most commonly associated with its rocket mechanism,[3] it originally consisted of a pouch of gunpowder attached to an arrow. This type of fire arrow served the function of an incendiary and was launched using a bow or crossbow.

According to the Wujing Zongyao the fire arrow was constructed and used in the following manner:

Behind the arrow head wrap up some gunpowder with two or three layers of soft paper, and bind it to the arrow shaft in a lump shaped like a pomegranate. Cover it with a piece of hemp cloth tightly tied, and sealed fast with molten pine resin. Light the fuse and then shoot it off from a bow.[4]

Incendiary gunpowder weapons had an advantage over previous incendiaries by using their own built-in oxygen supply to create flames, and were therefore harder to put out, similar to Greek fire. However, unlike Greek fire, gunpowder's physical properties are solid rather than liquid, which makes it easier to store and load.[4]

The rocket propelled fire arrow appeared later. By the mid-14th century, rocket arrow launchers had appeared in the Ming dynasty and later on mobile rocket arrow launchers that were utilized in China and later spread to Korea. The fire arrows propelled by gunpowder may have had a range of up to 1,000 ft (300 m).[5]

History

[edit]

The fire arrows were first reported to have been used by the Southern Wu in 904 during the siege of Yuzhang.[1]

In 969, gunpowder propelled rocket arrows were invented by Yue Yifang and Feng Jisheng.[7]

In 975, the state of Wuyue sent a unit of soldiers skilled in the handling of fire arrows to the Song dynasty. In the same year, the Song used fire arrows to destroy the fleet of Southern Tang.[8]

Published in 1044, the Wujing Zongyao, or Complete Compendium of Military Classics, states that in 994, the city of Zitong was attacked by a Liao army of 100,000 men who were driven back by regular war machines and fire arrows.[8][9]

In 1083, Song records state that the court produced 350,000 fire arrows and sent them to two garrisons.[10]

On March 1, 1126, the Song general Li Gang used a fire arrow machine known as the Thunderbolt thrower during the Jingkang Incident.[11]

By 1127, the Jin were also using fire arrows produced by captured Song artisans.[12]

In 1159, fire arrows were used by the Song navy in sinking a Jin fleet.[13]

In 1161, the general Yu Yunwen used fire arrows at the Battle of Caishi, near present-day Ma'anshan, during a Jin maritime incursion.[14]

By 1206, "gunpowder arrows" (huoyaojian) rather than just "fire arrows" (huojian) were mentioned.[15]

In 1245, a military exercise was conducted on the Qiantang River using what were probably rockets.[16][15]

The Mongols also made use of the fire arrow during their campaigns in Japan. Probably as a result of the Mongolian military campaigns the fire arrows later spread into the Middle East, where they were mentioned by Al Hasan Al Ramma in the late 13th century.[17]

In 1374, the kingdom of Joseon also started producing gunpowder and by 1377, was producing cannons and fire arrows, which they used against wokou pirates.[18][19] Korean fire arrows were used against the Japanese during the invasion of Korea in 1592.[20]

In 1380, an order of "wasp nest" rocket arrow launchers were ordered by the Ming army and in 1400, rocket arrow launchers were recorded to have been used by Li Jinglong.[21]

In 1451, a type of mobile rocket arrow launcher known as the "Munjong Hwacha" was invented in Joseon.[22]

The Japanese version of the fire arrow was known as the bo hiya. The Japanese pirates (wokou, also known as wako or kaizoku) in the 16th century were reported to have used the bo hiya which had the appearance of a large arrow. A burning element made from incendiary waterproof rope was wrapped around the shaft and when lit the bo hiya was launched from a mortar like weapon hiya taihou or a wide bore Tanegashima matchlock arquebus. During one sea battle it was said the bo hiya were "falling like rain".[23]

Rocket invention

[edit]The dating of the appearance of the gunpowder propelled fire arrow, otherwise known as a rocket, more specifically a solid-propellant rocket, is disputed. The History of Song attributes the invention to different people at different times, Yue Yifang and Feng Jisheng in 969 and Tang Fu in 1000. However, Joseph Needham argues that rockets could not have existed prior to the 12th century since the gunpowder formulas listed in the Wujing Zongyao are not suitable as rocket propellant.[24] According to Stephen G. Haw, there is only slight evidence that rockets existed prior to 1200 and it is more likely they were not produced or used for warfare until the latter half of the 13th century.[25]

Gallery

[edit]-

A fire arrow from the Wubei Zhi

-

Depiction of fire arrows known as "divine engine arrows" (shen ji jian 神機箭) from the Wubei Zhi.

-

Depiction of a stationary fire arrow (rocket arrow) launcher from the Huolongjing.

-

Illustration of a hwacha manual from the Gukjo-oryeui (國朝五禮儀, Five Rites of State)

-

An illustration of fire arrow launchers as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. The launcher is constructed using basketry.

-

A "charging leopard pack" rocket arrow launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi.

-

A "nest of bees" (yi wo feng 一窩蜂) rocket arrow launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. So called because of its hexagonal honeycomb shape.

-

A "long serpent" fire arrow launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. It carries 32 medium small poisoned rocket arrows and comes with a sling to carry on the back.

-

The 'convocation of eagles chasing hare arrow' from the Wubei Zhi. A double ended rocket arrow pod that carries 30 small poisoned rocket arrows on each end for a total of 60 rocket arrows. It carries a sling for transport.

-

A hwacha from the Yungwon pilbi

-

A life size reconstruction of a hwacha that launches singijeons - the Korean fire arrow.

-

Korean fire arrows

-

Antique Japanese (samurai) bo hiya or bohiya (fire arrow) and hiya taihou (fire arrow cannon), Kumamoto Castle, Japan.

-

Antique Japanese (samurai) bohiya or bo hiya (fire arrow), showing the fuse, Kumamoto Castle, Japan.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 31.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 68.

- ^ The History of Early Fireworks and Fire Arrows Archived 2020-04-10 at the Wayback Machine — About.com

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 154.

- ^ "History of Rocketry: Ancient times to the 17th Century". Spaceline.org. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 43, 259, 578.

- ^ Liang 2006.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 148.

- ^ This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age (Google eBook), William E. Burrows, Random House Digital, Inc., Nov 5, 1999P.8

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 32.

- ^ (靖康元年二月六日)是夕,宿于咸丰门,以金人进兵门外,治攻具故。先是,蔡楙号令将士,金人近城不得辄施放,有引炮及发床子弩者,皆杖之,将士愤怒。余(李纲)既登城,令施放,有引炮自便,能中(金)贼者,厚赏。夜,发「霹雳炮」以击,(金)贼军皆惊呼。(Rough Translation: [On March 1, 1126 (Gregorian calendar)] In the evening, I slept at the gate of Xianfeng, as the Jin army arrived at the gate and nourishing their weapons. Earlier, Cai Mao had ordered the men that they were not allowed to fire on the Jin soldiers whoever came near, any firing from trebuchets and ballistas were to be caned, and the soldiers were irritate by the order. Once arrived at the walls, I had ordered them to fire, for those who could hit the enemy were to be extensively rewarded. At night, they launched the "thunderbolt pao" at the enemy, and they were all shocked.) Records of Messages from the Jingkang Era ch. 2 (author: Li Gang)

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 34-35.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 39.

- ^ (绍兴辛已年)我舟伏于七宝山后,令曰:「旗举则出江!」。先使一骑偃旗于山之顶,伺其半济,忽山上卓立一旗,舟师自山下河中两旁突出大江,人在舟中,踏车以行船。但见船行如飞,而不见有人,(金)虏以为纸船也。舟中忽发一「霹雳炮」,盖以纸为之,而实之以石灰、硫黄。炮自空而下落水中,硫黄得水而火作,自水跳出,其声如雷,纸裂而石灰散为烟雾,眯其人马之目,人物不相见。(Rough Translation: [Year 1161] Once our ships had hid behind the Mount Qibao, an order was given to launch out followed after the signal. Earlier, a mounted scout was sent atop the peak to watch over half cross the river, suddenly a signal was shown from the peak, and the ships came out from the river on both sides at the foot, all men on board tread as to move the ship. The ships seemed to move swiftly without sails or oars, so the savages [Jin] conceived that those were paper boats. Then, the paddle wheelers launched the "thunderbolt pao" at their enemy on a sudden, which were made of paper pots, packed with lime and sulfur. When alight, they exploded upon impact with the water, and bounce out, making a noise like thunder. The pots were cracked and lime scattered into a smoky fog, blinding and terrifying the enemy men and horses.) Collection from the Sincerity Studio ch. 44 (author: Yang Wanli)

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 511.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 132.

- ^ Baker, David (1978). The Rocket: The History and Development of Rocket & Missile Technology. Crown. ISBN 978-0-517-53404-5.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 173.

- ^ 박성래 (2005). Science and Technology in Korean History: Excursions, Innovations, and Issues. Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-89581-838-6.

- ^ Haskew, Michael E.; Jorgensen, Christer; McNab, Chris; Niderost, Eric; Rice, Rob S. (2008-08-15). Fighting Techniques of the Oriental World 1200–1860: Equipment, Combat Skills and Tactics. Amber Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-905704-96-5.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 514.

- ^ "Articles of 1451, Munjongsillok of annals of Joseon Dynasty (from book 5 to 9, click 문종 for view)". National institute of Korean history. 1451. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2012-01-20). Pirate of the Far East: 811-1639. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-369-3.

- ^ Lorge 2005.

- ^ Haw 2013, p. 41.

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-82274-2.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2013), Cathayan Arrows and Meteors: The Origins of Chinese Rocketry

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lorge, Peter (2005), Warfare in China to 1600, Routledge

- Lu Zhen. "Alternative Twenty-Five Histories: Records of Nine Kingdoms". Jinan: Qilu Press, 2000. ISBN 7-5333-0697-X.

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3.