Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fon language

View on Wikipedia| Fon | |

|---|---|

| fɔ̀ngbè | |

| Native to | Benin, Nigeria, Togo |

| Ethnicity | Fon people |

Native speakers | 2.3 million (2019–2021)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin Gbékoun | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | fon |

| ISO 639-3 | fon – inclusive codeIndividual codes: guw – Gunmxl – Maxi Gbewem – Weme Gbe |

| Glottolog | fonn1241 Fon language |

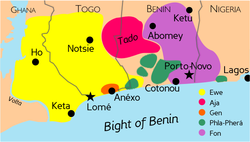

Gbe languages. Fon is purple. | |

| Person | Fon |

|---|---|

| People | Fon-nu |

| Language | fɔ̀ngbè |

| Country | Danhɔmɛ |

Fon (fɔ̀ngbè, pronounced [fɔ̃̀ɡ͡bē][2]), also known as Dahomean, is the language of the Fon people. It belongs to the Gbe group within the larger Atlantic–Congo family. It is primarily spoken in Benin, as well as in Nigeria and Togo by approximately 2.3 million speakers.[1] Like the other Gbe languages, Fon is an isolating language with a SVO basic word order.

Cultural and legal status

[edit]In Benin, French is the official language, and Fon and other indigenous languages, including Yom and Yoruba, are classified as national languages.[3]

Dialects

[edit]The standardized Fon language is part of the Fon cluster of languages inside the Eastern Gbe languages. Hounkpati B Christophe Capo groups Agbome, Kpase, Gun, Maxi and Weme (Ouémé) in the Fon dialect cluster, although other clusterings are suggested. Standard Fon is the primary target of language planning efforts in Benin, although separate efforts exist for Gun, Gen, and other languages of the country.[4]

Phonology

[edit]

Vowels

[edit]Fon has seven oral vowel phonemes and five nasal vowel phonemes.

| Oral | Nasal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| front | back | front | back | |

| Close | i | u | ĩ | ũ |

| Close-Mid | e | o | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | ɛ̃ | ɔ̃ |

| Open | a | ã | ||

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Labial -velar | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Nasal" | m ~ b | n ~ ɖ | ||||||||

| Occlusive | (p) | t | d | tʃ | dʒ | k | ɡ | kp | ɡb | |

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | x | ɣ | xʷ | ɣʷ | ||

| Approximant | l ~ ɾ | ɲ ~ j | w | |||||||

/p/ occurs in only linguistic mimesis and loanwords but is often replaced by /f/ in the latter, as in cɔ́fù 'shop'. Several of the voiced occlusives occur before only oral vowels, and the homorganic nasal stops occur before only nasal vowels, which indicates that [b] [m] and [ɖ] [n] are allophones. [ɲ] is in free variation with [j̃] and so Fong can be argued to have no phonemic nasal consonants, a pattern rather common in West Africa.[a] /w/ is nasalized (to [ŋʷ]) before nasal vowels, and may assimilate to [ɥ] before /i/. /l/ is sometimes also nasalized.[clarification needed]

The only consonant clusters in Fon have /l/ or /j/ as the second consonant. After (post)alveolars, /l/ is optionally realized as [ɾ]: klɔ́ 'to wash', wlí 'to catch', jlò [d͡ʒlò] ~ [d͡ʒɾò] 'to want'.

Tone

[edit]Fon has two phonemic tones: high and low. High is realized as rising (low–high) after a voiced consonant. Basic disyllabic words have all four possibilities: high–high, high–low, low–high, and low–low.

In longer phonological words, such as verb and noun phrases, a high tone tends to persist until the final syllable, which, if it has a phonemic low tone, becomes falling (high–low). Low tones disappear between high tones, but their effect remains as a downstep. Rising tones (low–high) simplify to high after high (without triggering downstep) and to low before high.

Hwevísatɔ́,

/ɣʷèví-sà-tɔ́

[ɣʷèvísáꜜtɔ́‖

fish-sell-agent

é

é

é

s/he

ko

kò

kó

PERF

hɔ

xɔ̀

ꜜxɔ̂

buy

asón

àsɔ̃́

àsɔ̃́

crab

we.

wè/

wê‖]

two

"The fishmonger, she bought two crabs."

In Ouidah, a rising or falling tone is realized as a mid tone. For example, mǐ 'we, you', phonemically high-tone /bĩ́/ but phonetically rising because of the voiced consonant, is generally mid-tone [mĩ̄] in Ouidah.

Orthographies

[edit]Roman alphabet

[edit]The Fon alphabet is based on the Latin alphabet, with the addition of the letters Ɖ/ɖ, Ɛ/ɛ, and Ɔ/ɔ, and the digraphs gb, hw, kp, ny, and xw.[6]

| Majuscule | A | B | C | D | Ɖ | E | Ɛ | F | G | GB | H | HW | I | J | K | KP | L | M | N | NY | O | Ɔ | P | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | XW | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minuscule | a | b | c | d | ɖ | e | ɛ | f | g | gb | h | hw | i | j | k | kp | l | m | n | ny | o | ɔ | p | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | xw | y | z |

| Sound (IPA) | a | b | t͡ɕ | d | ɖ | e | ɛ | f | ɡ | ɡb | ɣ | ɣʷ | i | d͡ʑ | k | kp | l | m | n | ɲ | o | ɔ | p | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | xʷ | j | z |

Tone marking

[edit]Tones are marked as follows:

- Acute accent marks the rising tone: xó, dó

- Grave accent marks the falling tone: ɖò, akpàkpà

- Caron marks falling and rising tone: bǔ, bǐ

- Circumflex accent marks the rising and falling tone: côfù

- Macron marks the neutral tone: kān

Tones are fully marked in reference books, but not always marked in other writing. The tone marking is phonemic, and the actual pronunciation may be different according to the syllable's environment.[7]

Gbékoun script

[edit]

Speakers in Benin also use a distinct script called Gbékoun that was invented by Togbédji Adigbè.[8][9] It has 24 consonants and 9 vowels, as it is intended to transcribe all the languages of Benin.

Sample text

[edit]From the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Acɛ, susu kpo sisi ɖokpo ɔ kpo wɛ gbɛtɔ bi ɖo ɖò gbɛwiwa tɔn hwenu; ye ɖo linkpɔn bɔ ayi yetɔn mɛ kpe lo bɔ ye ɖo na do alɔ yeɖee ɖi nɔvinɔvi ɖɔhun.

- Translation

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Use

[edit]Radio programs in Fon are broadcast on ORTB channels.

Television programs in Fon are shown on the La Beninoise satellite TV channel.[10]

French used to be the only language of education in Benin, but in the second decade of the twenty-first century, the government is experimenting with teaching some subjects in Benin schools in the country's local languages, among them Fon.[11][12][13]

Machine translation efforts

[edit]There is an effort to create a machine translator for Fon (to and from French), by Bonaventure Dossou (from Benin) and Chris Emezue (from Nigeria).[14] Their project is called FFR.[15] It uses phrases from Jehovah's Witnesses sermons as well as other biblical phrases as the research corpus to train a Natural Language Processing (NLP) neural net model.[16]

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is a matter of perspective; it could also be argued that [b] and [ɖ] are denasalized allophones of /m/ and /n/ before oral vowels.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Fon at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Gun at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Maxi Gbe at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Weme Gbe at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- ^ Höftmann & Ahohounkpanzon, p. 179

- ^ "Language data for Benin". Translators without Borders. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- ^ Kluge, Angela (2007). "The Gbe Language Continuum of West Africa: A Synchronic Typological Approach to Prioritizing In-depth Sociolinguistic Research on Literature Extensibility" (PDF). Language Documentation & Conservation: 182–215. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-11-11. Retrieved 2018-07-05.

- ^ a b Claire Lefebvre; Anne-Marie Brousseau (2002). A Grammar of Fongbe. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 15–29. ISBN 3-11-017360-3.

- ^ Höftmann & Ahohounkpanzon, p. 19

- ^ Höftmann & Ahohounkpanzon, p. 20

- ^ Teddy G. (May 5, 2021). "Vulgarisation de l'alphabet: Gbékoun sur tout le territoire national Bilan de la première phase de sensibilisation". Matin libre (in French).

- ^ "Alphabet " Gbékoun ": Un outil d'éveil de la conscience des peuples africains". La Nation (in French). June 21, 2021. p. 13.

- ^ "BTV - La Béninoise TV - La Béninoise des Télés | La proximité par les langues". www.labeninoisetv.net (in French). Archived from the original on 2018-07-03. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- ^ Akpo, Georges. "Système éducatif béninois : les langues nationales seront enseignées à l'école à la rentrée prochaine". La Nouvelle Tribune (in French). Archived from the original on 2019-06-21. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- ^ "Reportage Afrique - Bénin : l'apprentissage à l'école dans la langue maternelle". RFI (in French). 2013-12-26. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- ^ "Langues nationales dans le système scolaire : La phase expérimentale continue, une initiative à améliorer - Matin Libre" (in French). Archived from the original on 2018-07-03. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- ^ "AI in Africa: Teaching a bot to read my mum's texts". BBC News. 2020-04-29. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- ^ "Project website". ffrtranslate.com. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- ^ Emezue, Chris Chinenye; Dossou, Femi Pancrace Bonaventure (2020). "FFR v1.1: Fon-French Neural Machine Translation". Proceedings of the Fourth Widening Natural Language Processing Workshop. Seattle, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics: 83–87. arXiv:2003.12111. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.winlp-1.21.

Bibliography

[edit]- Höftmann, Hildegard; Ahohounkpanzon, Michel (2003). Dictionnaire fon-français : avec une esquisse grammaticale. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. ISBN 3896454633. OCLC 53005906.

External links

[edit]- A Facebook application to use and learn the Fon language, developed by Jolome.com

- The first blog totally in Fongbe. An access to a Fongbe forum is given

- Journal of West African Languages: Articles on Fon

- Manuel dahoméen : grammaire, chrestomathie, dictionnaire français-dahoméen et dahoméen-français, 1894 by Maurice Delafosse at the Internet Archive (in French)

Fon language

View on GrokipediaLinguistic Classification

Genetic Affiliation within Niger-Congo

The Fon language belongs to the Gbe cluster of languages, which is classified within the Volta-Niger branch of the Niger-Congo language family. This placement reflects a consensus among linguists based on comparative evidence, including shared morphological features such as multi-level noun class marking via prefixes and suffixes, serial verb constructions, and basic lexical cognates with other Volta-Niger languages like Yoruba and Igbo.[6] The Volta-Niger branch, comprising approximately 50 languages spoken by over 30 million people as of 2012, was formerly grouped under the broader Kwa category but reclassified in the late 20th century to better account for internal genetic relationships supported by phonological and syntactic parallels. The broader Niger-Congo phylum, encompassing roughly 1,650 languages and over 700 million speakers as estimated in 2000, derives its genetic unity primarily from Greenberg's 1963 mass lexical comparison, supplemented by reconstructed proto-forms for noun classes and verb extensions in subgroups like Volta-Congo.[7] However, the depth of affiliation beyond well-demonstrated branches such as Benue-Congo remains contentious, as regular sound correspondences are sparse outside Bantu and closely related groups, leading some scholars to question the phylum's coherence and advocate for narrower families based on rigorous historical reconstruction.[7] For Gbe languages like Fon, the evidence for Volta-Niger membership is stronger, rooted in shared innovations such as the reduction of nominal affixes and tonal systems distinguishing anterior/posterior aspects, distinguishing them from adjacent Gur or Kru branches.[8]Position in the Gbe Language Cluster

The Fon language holds a prominent position within the Gbe language cluster, serving as the eponymous core of the Fon subgroup, which is one of five major clusters identified in linguistic classifications of Gbe: Ewe, Fon, Aja, Gen (Mina), and Phla–Pherá.[9] This cluster structure emerges from phonological, morphophonological, and lexical analyses, with Fon varieties exhibiting high internal mutual intelligibility while showing moderate to low intelligibility with other Gbe clusters.[8] Fon is typically grouped under Eastern Gbe, alongside Aja and Gen clusters, distinguishing it from Western Gbe groups like Ewe and Phla–Pherá based on shared innovations in tone, vowel systems, and serial verb constructions.[10] Within the Fon cluster, core varieties include Agbome, Alada, Ayizo, Fon proper, Gbekon, Maxi, and Weme, primarily spoken in the Ouémé and Zou departments of southern Benin, where Fon functions as a prestige variety influencing neighboring dialects.[11] Quantitative lexical studies, such as multidimensional scaling of wordlists, confirm the cohesion of these Fon varieties, with Fon proper at the centroid, reflecting geographic and historical centrality tied to the Fon people's expansion from the Mono River region.[9] Divergences from Aja cluster varieties, such as Sethi and Tɔli, appear in nasalization patterns and labial-velar consonants, underscoring Fon's distinct yet continuum-linked role in Eastern Gbe.[8] Classificatory proposals, including those by Capo (1988, 1991), emphasize Gbe's dialect continuum nature, with Fon bridging Aja to the west and Gen to the east through transitional forms like Gun (Gungbe), which shares up to 80% lexical similarity with standard Fon.[12] Ethnographic and geolinguistic surveys highlight Fon's role in unifying Eastern Gbe speech communities, though lexical distance metrics reveal gradients rather than sharp boundaries, supporting its position as a pivotal node in the cluster's internal diversity.[10] This positioning aligns with Gbe's broader Volta–Niger affiliation, where shared archaisms like nine-vowel systems reinforce cluster integrity against external Kwa influences.[13]Debates on Language versus Dialect Status

The Gbe speech varieties, including Fon, form a dialect continuum spanning southeastern West Africa, where mutual intelligibility decreases with geographic distance due to gradual phonetic, lexical, and grammatical shifts, prompting debates on whether Fon constitutes a distinct language or a dialect of a larger Gbe entity.[10] Sociolinguistic surveys indicate high comprehension of Fon among proximate varieties like Ayizo (over 80% intelligibility in recorded text tests) and Kotafon, but only partial or minimal understanding in farther ones such as Saxwe (around 40-60%) or Ewe, underscoring that intelligibility alone does not resolve the continuum's chaining pattern.[10] [8] Linguists like those from SIL International classify Gbe components, including Fon, as a "continuum" of varieties rather than strictly dialects or languages, avoiding binary distinctions influenced by political boundaries—Fon standardized in Benin as a national language with literacy materials since the 1970s, while Ewe holds similar status in Togo and Ghana.[10] [14] In 1980, the Fourteenth West African Languages Congress at Cotonou adopted "Gbe" (meaning "language" in the varieties) as a neutral cover term for approximately 20-25 closely related forms, recognizing shared innovations within the Kwa branch of Niger-Congo but rejecting a single transdialectal standard due to ethnolinguistic fragmentation.[10] [9] Proponents of Fon as a separate language emphasize its institutional development, including ISO 639-3 code "fon," over 2 million L1 speakers as of 2023 estimates, and endogenous standardization efforts predating colonial influences, which differentiate it from less codified Gbe forms.[14] [10] Conversely, quantitative lexical studies reveal 85-95% similarity between Fon and core Gbe varieties like Gun, supporting arguments for dialect status within a macrolanguage framework, though such metrics undervalue functional barriers like divergent tone systems and syntax in distant pairs.[15] [9] No consensus exists, as classifications often reflect practical needs for Bible translation or education rather than purely linguistic criteria, with Ethnologue listing Fon as a primary language in its Gbe subgroup while noting the broader continuum's fluidity.[16] [14]Historical Development

Origins among the Fon People

The Fon language emerged as the vernacular of the Fon ethnic group, whose oral traditions trace ancestral origins to Tado, a settlement on the Mono River in present-day Togo associated with early Aja-speaking populations.[2] This region served as a dispersal point for related groups, with Fon forebears migrating eastward into the territory of modern southern Benin, where they differentiated culturally and linguistically from neighbors such as the Aja to the west and Mahi to the north.[2] The migration, linked in legends to intergroup movements and settlements, positioned the Fon in fertile coastal plains conducive to agricultural expansion and social organization, fostering the language's entrenchment as a medium for kinship, governance, and ritual communication.[17] Linguistic evidence situates Fon within the Gbe cluster of the Niger-Congo family, suggesting its proto-form arose from shared Volta-Niger substrates during these migrations, with Fon-specific innovations—including nasal vowels and tonal distinctions—crystallizing as the group consolidated in the Abomey plateau area by the late medieval period.[18] Ethnogenetic processes, including alliances and conflicts with adjacent peoples like the Gun and Ayizo, further shaped Fon's lexical and phonological profile, embedding terms for local ecology, Vodun deities, and political hierarchy reflective of Fon societal evolution.[2] While precise dating remains inferential from oral genealogies rather than written records, archaeological correlations with ironworking sites in the Mono region support an origins timeline predating the 17th-century founding of the Dahomey Kingdom, under which Fon solidified as a prestige variety.[19] The language's resilience amid these dynamics underscores its role in preserving Fon identity, transmitted orally through griots and initiatory societies long before European transcription efforts.Documentation and Early Records

The Fon language, lacking an indigenous writing system, relied on oral transmission among speakers until European contact introduced the Latin script in the 19th century. Initial European records emerged in the 17th century amid trade interactions with the Kingdom of Dahomey, particularly at coastal ports like Ouidah, where Portuguese, Dutch, and French traders documented basic vocabularies and phrases primarily for commerce and the slave trade. These fragmentary accounts, often embedded in travel narratives, represent the earliest written attestations of Fon lexical items, though they lacked systematic analysis.[20] Systematic linguistic documentation commenced in the 19th century through explorers and early missionaries. British explorer Richard Francis Burton's 1864 publication A Mission to Gelele, King of Dahomey included observations on Fon phonology, vocabulary, and usage derived from his embassy to the Dahomean court, providing one of the first detailed English-language references to the language. Subsequent missionary efforts produced vocabularies and rudimentary grammars, laying groundwork for later standardization, though full reference grammars, such as those analyzing serial verb constructions and tonal systems, appeared primarily in the 20th century.[21]Influence of the Kingdom of Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey, established by Fon leaders around 1620 in the region of Abomey, positioned the Fon language as the dominant medium of governance and cultural expression in southern Benin. As the tongue of the royal court and military elite, Fon—also termed Danmegbe or "language of Dahomey"—served administrative functions, including command structures and diplomatic exchanges during the kingdom's expansion against neighboring groups like the Yoruba-speaking Oyo Empire.[2] This central role fostered a prestige variety of Fon, particularly the Abomey dialect, which influenced linguistic norms across conquered territories and integrated lexical elements related to warfare, trade, and Vodun cosmology.[22] Fon's oral traditions thrived under Dahomean patronage, with court poets (gbonu-gan) composing praise chants (recades) and historical epics that chronicled royal lineages from founder Houegbadja onward. These genres, performed at annual customs like the Xwetanu festival, preserved and propagated Fon phonological patterns, tonal melodies, and idiomatic expressions tied to state ideology.[23] The kingdom's involvement in the Atlantic slave trade from the late 17th century introduced limited Portuguese and English loanwords into Fon lexicon, particularly for trade goods and weaponry, though the core structure remained intact due to the oral-exclusive nature of Fon documentation until European missionary efforts in the 19th century.[24] By the reign of King Ghezo (1818–1858), Fon's prestige extended regionally, absorbing substrate influences from Aja and Gen subgroups while asserting dominance over other Gbe varieties through Dahomey's conquests, which expanded the kingdom's territory to the Atlantic coast by 1730. This period marked no formal standardization but reinforced Fon's vitality as a vehicle for political unity, with ritual liturgies and proverbs embedding causal narratives of power and divine favor central to Fon worldview.[25] The kingdom's fall to French forces in 1894 preserved Fon's oral heritage, which later informed post-colonial linguistic efforts, underscoring Dahomey's enduring role in elevating it from a local vernacular to a symbol of historical authority.[26]Geographic Distribution

Primary Speaking Regions

The Fon language is predominantly spoken in the southern regions of Benin, where it functions as a primary vernacular among the Fon ethnic group, concentrated in areas surrounding historic centers like Abomey and extending to coastal urban hubs such as Cotonou and Porto-Novo.[4] This region encompasses departments including Atlantique, Littoral, Ouémé, and Zou, reflecting the historical territory of the Kingdom of Dahomey. Fon serves as a lingua franca in southern Benin, spoken as a first language by approximately 20% of the national population, with higher prevalence in these southern zones due to urban density and ethnic distribution.[4] In neighboring Togo, Fon speakers are primarily located in the southern Plateaux and Maritime regions, adjacent to the Benin border, with an estimated 35,500 speakers reported as of 1991.[27] The language maintains vitality in these border communities, often alongside Ewe and other Gbe varieties.[28] Fon is also spoken by minority communities in southwestern Nigeria, particularly in Ogun and Lagos states, where it overlaps with Yoruba-speaking areas and reflects historical migrations and trade links.[29] Speaker numbers in Nigeria are smaller and integrated into multilingual settings, contributing to the overall Gbe language continuum across the Benin-Nigeria-Togo tripoint.[30]Speaker Demographics and Vitality

Fon is spoken primarily in southern Benin and adjacent regions of Togo by an estimated 3 million native speakers, concentrated among the Fon ethnic group, which forms Benin's largest ethnic community. In Benin, linguistic data indicate that Fon serves as the first language for approximately 24% of the population, equating to over 3 million individuals given the country's total population of around 13.5 million as of 2023. Additional speakers, including second-language users, extend its reach, particularly as a lingua franca in urban areas like Cotonou, where it facilitates communication across ethnic lines in southern Benin. Smaller communities exist in eastern Togo, Nigeria, and diaspora populations in Gabon and Europe, though these number in the tens of thousands.[31][28] The language demonstrates robust vitality, classified as stable with no significant intergenerational transmission issues or shift toward dominant languages like French. Sociolinguistic surveys by SIL International reveal high comprehension and positive attitudes toward Fon among related Gbe-speaking groups, with speakers viewing it favorably for both oral and written domains. Institutional support bolsters its status, including its role in primary education curricula, national radio and television broadcasts, and local governance in Benin, where it is recognized as a national language alongside others. No evidence from recent assessments points to endangerment, contrasting with smaller Gbe varieties; instead, urbanization and media exposure sustain its use among younger generations.[32][33][28]Dialectal Variation

Major Dialects and Subgroups

The Fon cluster within the Eastern Gbe languages consists of several mutually intelligible varieties classified by linguist H. B. C. Capo as dialects of Fon, including Agbome, Kpase, Gun, Maxi, and Weme (Ouémé). Agbome, centered around Abomey in central Benin, forms the foundation of standardized Fon, which is used in literacy programs, broadcasting, and official contexts since its promotion in the mid-20th century under Benin's post-independence language policies.[9] Kpase, spoken near Porto-Novo, exhibits phonological variations such as distinct vowel realizations but retains high lexical similarity (over 90%) with Agbome, supporting its dialect status.[8] Gun (Gungbe), prevalent in southeastern Benin along the Nigeria border, is integrated into the Fon cluster by Capo and others due to shared grammatical structures like serial verb constructions and tonal patterns, though some classifications treat it as a coordinate language owing to geographic separation and minor syntactic divergences. Maxi and Weme, found in the Ouémé department and along the riverine areas, feature localized innovations in lexicon influenced by trade with neighboring groups, yet demonstrate intelligibility levels of 80-85% with core Fon varieties based on SIL sociolinguistic surveys conducted in the 1980s-1990s.[9] Additional subgroups like Alada and Ayizo are variably included in expanded Fon classifications, reflecting the dialect continuum's fluidity across Benin and Togo.[8] These dialects arose from historical migrations of Fon-speaking groups from the Allada kingdom northward to Abomey in the 17th century, with subgroups differentiating through contact with Aja and Gen varieties. Standardization efforts, primarily around Agbome since the 1970s, have prioritized unity over subgroup diversity, but challenges persist due to uneven intelligibility in peripheral areas like Weme, where French loanwords further diverge speech.[9]Mutual Intelligibility and Standardization Challenges

Fon dialects belong to the Eastern Gbe cluster, encompassing varieties such as Agbome, Arohun, Gun, Kpase, Maxi, and Weme, which exhibit a chaining pattern of mutual intelligibility typical of dialect continua. Comprehension tests reveal high intelligibility between Fon and proximate dialects like Ayizo and Kotafon, while more distant ones, such as Saxwe, show only partial understanding. Across the broader Gbe continuum of 49 varieties, average lexical similarity stands at 64% and grammatical similarity at 52%, with intelligibility testing recommended when lexical overlap surpasses 70%.[10][8] Standardization of Fon, known as Fongbe, relies primarily on the Agbome dialect from Abomey, leveraging its prestige from the historical Kingdom of Dahomey for use in Benin's education, media, and language planning since the 1990s. However, the lack of a transdialectal variety fully intelligible across all Gbe speech forms poses significant challenges, exacerbated by the continuum's gradual variations and distinct ethnolinguistic identities that resist unification. Efforts to develop orthography and vocabulary encounter hurdles in securing consensus among diverse communities, further complicated by French's official status and limited resources for peripheral dialects.[34][10][8]Phonological System

Vowel Inventory and Harmony

The Fon language possesses a vowel inventory of seven oral vowels, transcribed as /i/, /e/, /ɛ/, /a/, /ɔ/, /o/, and /u/, which exhibit four degrees of aperture (high, upper-mid, lower-mid, and low). These vowels are distinguished primarily by height and backness, with /e/ and /o/ representing advanced tongue root (+ATR) variants of the mid series, contrasting with the retracted tongue root (-ATR) /ɛ/ and /ɔ/. The system lacks phonemic lax high vowels, resulting in an asymmetric structure typical of many Gbe languages. Nasal vowels number five, generally /ĩ/, /ɛ̃/, /ã/, /ɔ̃/, and /ũ/, with three degrees of aperture and no nasal counterparts for /e/ and /o/, as nasalization of those tends to lower them to /ɛ̃/ and /ɔ̃/ in phonetic realization.[35][36]| Oral Vowels | Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Upper Mid | e | o | |

| Lower Mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Low | a |

| Nasal Vowels | Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | ĩ | ũ | |

| Lower Mid | ɛ̃ | ã | ɔ̃ |

Consonant System

The consonant system of Fon (also known as Fongbe) features 22 phonemic consonants, spanning plosives, fricatives, nasals, a lateral, a rhotic, and glides, with no phonemic aspiration, implosion, or ejection.[39] These consonants are articulated at bilabial, labiodental, alveolar, postalveolar, palatal, velar, labiovelar, and glottal places, following typical Kwa language patterns without labialized or prenasalized series as distinct phonemes.[39] Voiceless plosives /p t k kp/ are unaspirated, while voiced counterparts /b d g gb/ exhibit lenition tendencies intervocalically, often realized as approximants or flaps in casual speech.[39] The inventory is presented below in a standard phonological chart:| Manner \ Place | Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Labiovelar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p, b | t, d | k, g | kp, gb | ||||

| Fricative | f, v | s, z | ʃ, ʒ | h | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||

| Lateral | l | |||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||

| Glide | w | j |