Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gorget

View on Wikipedia

A gorget (/ˈɡɔːrdʒɪt/ GOR-jit; from Old French gorge 'throat') is a band of linen that was wrapped around a woman's neck and head in the medieval period or the lower part of a simple chaperon hood.[2][3] The term later described a steel or leather collar to protect the throat, a set of pieces of plate armour, or a single piece of plate armour hanging from the neck and covering the throat and chest. Later, particularly from the 18th century, the gorget became primarily ornamental, serving as a symbolic accessory on military uniforms, a use which has survived in some armies (see below).

The term may also be used for other things such as items of jewellery worn around the throat region in several societies, for example wide thin gold collars found in prehistoric Ireland dating to the Bronze Age.[4]

As part of armour

[edit]

In the High Middle Ages, when mail was the primary form of metal body armour used in Western Europe, the mail coif protected the neck and lower face. In this period, the term gorget seemingly referred to textile (padded) protection for the neck, often worn over mail. As more plate armour appeared to supplement mail during the 14th century, the bascinet helmet incorporated a mail curtain called the aventail which protected the lower face, neck and shoulders. A separate mail collar called a "pisan" or "standard" was sometimes worn under the aventail as additional protection.[6] Towards the end of the 14th century, threats including the increased penetrating power of the lance when paired with a lance rest on the breastplate made more rigid forms of neck protection desirable. One solution was a standing collar plate separate from the helmet that could be worn over the aventail, with enough space between the collar and helmet that a man-at-arms could turn his head inside it. In the early 15th century, such collar plates were integrated into the helmet itself to form the great bascinet.[7] Other forms of helmet such as the sallet which did not protect the lower face and throat with plate were paired with a separate bevor, and the armet was often fitted with a wrapper that included gorget lames protecting the throat. The mail standard was still worn under such bevors and wrappers, since the plates did not cover the back or sides of the neck.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the gorget reached its full development as a component of plate armour. Unlike previous gorget plates and bevors which sat over the cuirass and also required a separate mail collar to fully protect the neck, the developed gorget was worn under the cuirass and was intended to cover a larger area of the neck, nape, shoulders and upper chest, from which the edges of the backplate and breastplate had receded. The gorget served as an anchor point for the pauldrons, which either had holes in them to engage pins projecting from the gorget, or straps which could be buckled to the gorget. The neck was protected by a high collar of articulated lames, and the entire gorget was divided into front and back pieces which were hinged at the side so that the gorget could be put on and taken off. Some helmets had additional neck lames which overlapped the gorget, while others formed a tight seal with the rim of the gorget to eliminate any gaps.

By the 17th century there appeared a form of gorget with a low, unarticulated collar and larger front and back plates which covered more of the upper chest and back. In addition to being worn under the breast & backplates, as evidenced by at least two contemporary engravings, they were also commonly worn over civilian clothing or a buff coat. Some gorgets of this period were "parade" pieces that were beautifully etched, gilded, engraved, chased, embossed or enameled at great expense. Gradually the gorget grew smaller and more symbolic, becoming a single crescent shape worn on a chain which suspended the gorget ever lower on the chest, so that the gorget no longer protected the throat in normal wear.

The Japanese (samurai) form of the gorget, called a nodowa, was either fastened by itself around the neck or came as an integral part of the face defence or men yoroi. It consisted of several lames made of lacquered leather or iron, each of which either consisted of one piece or of scales laced together in horizontal rows. The lames were articulated vertically, overlapping bottom to top, by another set of silk laces.

As part of military uniforms

[edit]

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, crescent-shaped gorgets of silver or silver gilt were worn by officers, mainly infantry, in most European armies, as a badge of rank and an indication that they were on duty. These last vestiges of armour were much smaller (usually about 7 to 10 cm (2.8 to 3.9 in) in width) than their Medieval predecessors and were suspended by cords, chains or ribbons. In the British service they carried the Royal coat of arms until 1796 and thereafter the Royal Cypher.[8] During the reign of Napoleon I, the French ones carried often a design with the imperial eagle, the regimental number, a hunting horn or a flaming grenade, but non-regulation designs were not uncommon. Gorgets ceased to be worn by British army officers in 1830 and by their French counterparts 20 years later. They were still worn to a limited extent in the Imperial German Army until 1914, as a special distinction by officers of the Prussian Gardes du Corps and the 2nd Cuirassiers "Queen". Officers of the Spanish infantry continued to wear gorgets with the cypher of King Alfonso XIII in full dress, until the overthrow of the Monarchy in 1931. Mexican Federal army officers also wore the gorget with the badge of their branch as part of their parade uniform until 1947.[citation needed]

The gorget was revived as a uniform accessory in Nazi Germany, seeing widespread use within the German military and Nazi party organisations, mainly units with a police function and their flag bearers. During World War II, it continued to be used by Feldgendarmerie (military field police), who wore metal gorgets as emblems of authority. German police gorgets of this period typically took the form of flat metal crescents with ornamental designs that were suspended by a chain worn around the neck. These designs and lettering were painted with illuminating paint.

The Prussian-influenced Chilean army uses the German style metal gorget in parades and in the uniform of their Military Police.[9]

In Sweden

[edit]As early as 1688, regulations were provided for the wearing of gorgets by Swedish army officers. For those of captain's rank the gorget was gilt with the king's monogram under a crown in blue enamel, while more junior officers wore silver-plated gorgets with the initials in gold.[10]

The gorget was discontinued as a rank insignia for Swedish officers in the Swedish Armed Forces in 1792, when epaulettes were introduced. The gorget was revived in 1799, when the Officer of the day was given the privilege of wearing a gorget which featured the Swedish lesser coat of arms. It has since been a part of the officer's uniform (when he or she functions as "Officer of the day") a custom which continues.[citation needed]

-

Early Swedish gorget from the time of king Charles XI of Sweden for a colonel.

-

Gorget in silver for ensigns and lieutenants of the Swedish Army, with the royal cypher of Gustav III Swedish Army Museum.

-

Gorget, silver gilt, for a captain with the royal cypher of Gustav III in enamel. Swedish Army Museum.

-

Gorget, silver gilt, for majors, lieutenant-colonels and colonels of the Swedish Army, with the royal cypher of Gustav III and two palm branches, all enameled. Swedish Army Museum.

-

Arvid Horn in a uniform with a gorget for the captain lieutenant of the Kunglig Majestäts drabanter, the gorget with the royal cypher of Charles XII of Sweden, ca 1706.

-

Peter Lilliehorn in the uniform and gorget of a major at the Kalmar Regiment, the gorget with the royal cypher of Frederick I of Sweden, 1727.

-

Swedish gorget model 1799 for the officer of the day. Swedish Army Museum.

In Norway and Finland

[edit]The same use of the gorget also continues in Norway and Finland, worn by officers or corporals responsible for guard changes and "Inspecting Officers" (officer of the day). The officer of the day of a company (Finnish: päivystäjä) is usually a non-commissioned officer (or even a private), who guards the entrance and is responsible for security within company quarters.

Gorget patches

[edit]

The scarlet patches still worn on each side of the collar of the tunics of British Army general officers and senior officers are called "gorget patches" in reference to this article of armour. There were two types - the first, red with a crimson centre stripe, were for Colonels and Brigadiers, and red with a gold centre stripe for General Officers. Today, they signify an officer of the General Staff, to which all British officers are appointed on reaching the rank of Colonel. With limited exceptions such as senior officers of the Army Medical and Dental Corps, the historic colour differentials are no longer worn in the British service.[citation needed]

However, the historic colours are still used in the gorget patches of the Canadian Army. Air officers in the Indian and Sri Lankan air forces also wear gorget patches with one to five stars depending on their seniority.[11]

RAF officer cadets wear white gorget patches on their service dress and mess dress uniforms. Very similar collar patches are worn by British army officer cadets at Sandhurst on the standup collars of their dark-blue "Number One" dress uniforms. These features of modern uniforms are a residual survival from the earlier practice of suspending the actual gorgets from ribbons attached to buttons on both collars of the uniform. Such buttons were often mounted on a patch of coloured cloth or gold embroidery.[citation needed]

Cultural and decorative uses

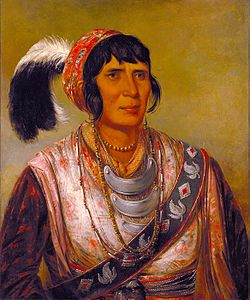

[edit]Gorgets made of shell, as well as stone and copper,[12] have been found at archaeological sites of various ages associated with mound building cultures of Eastern North America, going back thousands of years.[citation needed]

Gorget stones are polished pieces of stones that were worn by Native Americans on the neck or chest as a decoration, ornament, or talisman.[13]

The British Empire awarded gorgets to chiefs of American Indian tribes, both as tokens of goodwill, and as a badge of their high status.[14] Those being awarded a gorget were known as gorget captains [15] Gorgets were also awarded to African chiefs.[16]

In colonial Australia, gorgets were given to Aboriginal people by government officials and pastoralists as insignia of high rank or reward for services to the settler community. Frequently inscribed with the word "King" along with the name of the tribal group to which the recipient belonged (despite the absence of this kind of rank among indigenous Australians), the "breastplates", as they came to be known.[17]

Modern versions

[edit]

Recent advances in protective armour have led to the functional gorget being reintroduced into the US Army and Marine Improved Outer Tactical Vest and Modular Tactical Vest systems respectively.[citation needed]

Other uses

[edit]The state flag of South Carolina features a crescent in the upper left quadrant which now resembles a crescent moon, but which some oral traditions have suggested may have once represented a gorget. The state flag derives from a flag designed by Colonel William Moultrie in 1775 with a blue ground and crescent based on the uniforms of the Second South Carolina Regiment, who wore a crescent with the tips pointing up on their hats. Through the 19th century, the crescent on the state flag also appeared with the tips pointing up, and it was not until the 20th century that it was turned on its side to resemble a crescent moon. The mystery of its original meaning is still unresolved, and the crescent as it appears on the modern state flag is normally interpreted as a moon.[18]

The term also refers to a patch of coloured feathers found on the throat or upper breast of some species of birds.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lossing, Benson John (1859). Mount Vernon and its Associations: Historical, Biographical and Pictorial. Selected Americana from Sabin's Dictionary. W.A. Townsend and Company. p. 345. OCLC 9269788.

- ^ Norris, Herbert (1999). Medieval costume and fashion. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. pp. 181. ISBN 9780486404868.

- ^ Lewandowski, Elizabeth J. (24 October 2011). The complete costume dictionary. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 123. ISBN 9780810877856.

- ^ Gleeson, Dermot F. (1934). "Discovery of Gold Gorget at Burren, Co. Clare". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 4 (1): 138–139. JSTOR 25513720.

- ^ Cahill, Mary. "Before the Celts: treasures in gold and bronze". In:Ó Floinn, Raghnal; Wallace, Patrick (eds), Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities. National Museum of Ireland, 2002. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-7171-2829-7

- ^ Ian LaSpina, "Defense for the Throat: A Layered Approach", Nov 1, 2015

- ^ Ian LaSpina, "Helmets: The Great Bascinet", Nov 21, 2015

- ^ Carman, W.Y. (1977). A Dictionary of Military Uniform. Scribner. p. 66. ISBN 0-684-15130-8.

- ^ Rinaldo D. D' Ami, Page 43, World Uniforms in Colour. Volume 2. Nations of America, African, Asia and Oceania. 1969 Patrick Stephens Ltd London, SBN 85059 040 X

- ^ Preben Kannik, Alverdens Uniformer I Farver, p. 151

- ^ "Collar Tabs". Archived from the original on 2009-12-30. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ^ Waldman, Carl (2000). Atlas of the North American Indian, Revised Edition. Illustrated by Molly Braun. Checkmark Books, An imprint of Facts On File, Inc. p. 22. ISBN 0-8160-3975-5.

- ^ "Black Slate Gorget · Virginia Indian Archive".

- ^ p.9 Handbook of North American Indians: History of Indian-White Relations Government Printing Office, 1978

- ^ p. 286 Blegen, Theodore Christian & Heilbron, Bertha Lion Minnesota History Minnesota Historical Society, 1928

- ^ p.41 History of the Civilization and Christianization of South Africa; from its first settlement by the Dutch to the final surrender of it to the British Waugh & Innes, 1832

- ^ "National Museum of Australia: Aboriginal Breastplates". Archived from the original on 2011-12-07. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ^ Hicks, Brian (July 11, 2007). "What the heck is that doodad on our state flag?". The Post and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina.

- ^ Campbell, Bruce; Lack, Elizabeth, eds. (1985). A Dictionary of Birds. Calton, Staffs, England: T & A D Poyser. p. 254. ISBN 0-85661-039-9.

External links

[edit]- Australian Aboriginal breastplates Archived 2011-12-07 at the Wayback Machine

Gorget

View on GrokipediaA gorget is a collar-like element of armor intended to safeguard the throat and upper chest, prominently featured in European plate armor from the late medieval period onward.[1][2] The term originates from the Old French gorgete, a diminutive of gorge signifying "throat," reflecting its primary defensive role against strikes to this vulnerable area.[3] Initially constructed from rigid metal plates—often steel or leather—that articulated with helmets and breastplates, gorgets provided essential protection in close combat while allowing head mobility.[4][5] As full suits of plate waned in the 17th and 18th centuries with the rise of firearms and lighter uniforms, gorgets persisted as ornamental badges denoting officer rank in European armies, typically fashioned as crescent-shaped silver or gilt pieces suspended from the neck.[6][2] These evolved from practical armor into symbols of authority, engraved with regimental motifs or royal ciphers, and were notably exchanged with Native American allies or leaders by colonial powers as diplomatic gifts or trade items.[6][7] In vestigial modern forms, such as gorget patches on collars, they continue to signify staff roles or general officer status in select militaries, underscoring a transition from battlefield utility to ceremonial distinction.[8][9]

Etymology and Core Definitions

Linguistic Origins and Evolution

The English term "gorget" derives from the late 15th-century Old French gorgete, a diminutive of gorge ("throat"), entering Middle English to denote protective covering for the neck region.[3] This etymology underscores its anatomical focus, originating from the Vulgar Latin gurga (a variant of gurges, implying a gushing or swallowing passage akin to the gullet), which evolved in Old French to specify the throat itself.[1] Early attestations in English, around 1480–1500, applied the word to both civilian linen bands worn by women as neckwear and emerging military adaptations for throat defense over mail armor.[10] Linguistically, the term's adoption coincided with the diffusion of plate armor terminology during the Late Middle Ages, distinguishing the gorget as a specialized garniture component separate from the cuirass or bevor.[11] By the 16th century, English usage solidified around rigid collars of steel or hardened leather, reflecting technological shifts in metallurgy and combat needs, while retaining the French diminutive suffix to evoke a compact, throat-encircling form.[5] Parallel developments in Romance languages, such as Italian gorgetta, preserved similar throat-protective connotations in armorial contexts. Semantic evolution accelerated in the 17th–18th centuries as functional plate declined with firearm prevalence; "gorget" increasingly signified ornamental badges in European officer uniforms, transitioning from literal protection to symbolic rank insignia without altering the core throat-referential root.[12] This shift is evident in British military inventories by 1700, where gorgets bore regimental cyphers yet evoked archaic armor, a usage persisting into modern ceremonial contexts like some air forces' collar patches.[6] The word's extension to non-military senses, such as ornithological throat patches or jewelry, further illustrates metaphorical broadening from the physical throat to any banded neck feature, though these remain secondary to its armorial heritage.[13]Primary Functions Across Contexts

In medieval and Renaissance armor, the gorget's primary function was to shield the wearer's neck, throat, and upper chest from slashing, thrusting, and projectile wounds, forming a crucial link between helmet and cuirass.[14] Typically constructed from articulated steel lames or plates, it provided flexible yet robust defense, often worn over a buff coat or chainmail for added layers against edged weapons.[15] This protective role emerged prominently in the late 14th century as plate armor evolved to counter the vulnerabilities exposed in earlier mail defenses.[16] By the 18th century, with the obsolescence of full plate in favor of firearms and lighter tactics, the gorget shifted to an ornamental insignia denoting officer rank in European infantry and dragoon units.[2] Suspended by chains or ribbons, these crescent-shaped silver or gilt pieces symbolized commissioned authority, as formalized in British warrants from 1684 onward, distinguishing captains and lieutenants by design and finish.[11] The vestigial form retained echoes of its armored origins while serving ceremonial and hierarchical purposes in parade and duty uniforms.[17] Beyond European military traditions, gorgets functioned as status markers in indigenous North American contexts, where pre-contact shell examples from Mississippian cultures (circa 1250–1350 CE) indicated elite rank or ritual significance through engraved motifs.[18] Colonizers later gifted metal gorgets to Native leaders during the 18th–19th centuries as diplomatic tokens of alliance or honorary rank, adapting the European symbol to confer prestige in fur trade and treaty negotiations.[6] These items, often personalized with engravings, blended adornment with political utility across cultural exchanges.[19]Applications in Personal Armor

Design Features and Materials

The gorget in personal armor functioned primarily as a collar-like defense for the neck and throat, typically constructed from one or more shaped steel plates that encircled the vital area while permitting limited head rotation. Late medieval and Renaissance examples often featured articulated designs with overlapping lames—narrow horizontal plates—connected via leather straps or sliding rivets, enabling flexion to accommodate movement during combat without exposing gaps. This construction deflected downward strikes from swords or polearms, with some models incorporating a pivoting bevor plate to shield the chin and lower face.[20] Materials centered on high-quality steel, forged for impact resistance and occasionally surface-hardened through tempering or quenching processes to enhance durability against penetration. Leather served critical roles in internal padding for comfort, hinge mechanisms for articulation, and external straps for securing the piece to the breastplate or standalone wear over a buff coat—a robust leather doublet. Decorative enhancements, such as gold damascening, etching, or copper alloy inlays, appeared on elite examples, combining functionality with heraldic display, as seen in German gorgets circa 1550 weighing approximately 2 pounds.[21][15] Variations in plate thickness and edging—such as roped or fluted borders—optimized structural integrity, with steel gauges equivalent to modern 14-18 gauge providing a balance between protection and weight, typically under 3 pounds for the assembly. These elements evolved to integrate seamlessly with full harnesses, prioritizing causal effectiveness in redirecting force over rigid immobility.[20][15]Historical Development from Medieval to Renaissance Periods

In the 14th century, as plate armor began supplementing chainmail hauberks, gorgets developed as specialized collars to protect the vulnerable throat and upper chest from slashing weapons. Initially simple metal plates or reinforced fabric worn over mail, they addressed gaps left by helmets and torso defenses during the late medieval period.[22][23] By the 15th century, amid the transition to full plate harnesses, gorgets evolved into articulated structures of overlapping lames, enhancing mobility while sealing the junction between the helmet—such as the sallet or armet—and the cuirass. This design iteration, common in Gothic-style armors, incorporated bevors for lower facial coverage, reflecting advancements in armoring techniques that prioritized comprehensive enclosure without sacrificing articulation.[4] Entering the Renaissance in the early 16th century, gorgets achieved their most refined form as integral components of three-quarter or full plate armors, often comprising multiple flexible plates worn beneath the breastplate to cover a broader area including the collarbones. Exemplified by German examples circa 1525, these steel constructions featured polished surfaces and precise riveting for seamless integration, balancing protection against thrusts and cuts with wearer comfort.[24][25] This maturation coincided with the era's emphasis on ergonomic design, as seen in armors from Milanese and Augsburg workshops, where gorgets supported increasingly complex garnitures for field and tournament use.[26]Protective Effectiveness and Limitations

The gorget served as a vital component of late medieval and Renaissance plate armor, primarily defending the throat and upper collarbone against slashing wounds from edged weapons and thrusting attacks from spears or swords, areas left exposed or inadequately shielded by earlier chainmail aventails.[4] Constructed from overlapping tempered steel lames, typically 1-2 mm thick, articulated gorgets allowed partial flexion to accommodate helmet movement while distributing impact forces across multiple plates, thereby reducing the risk of localized penetration.[27] Historical analyses indicate that well-forged examples resisted direct lance thrusts and sword cuts effectively, as the hardened steel surface deflected blades or caused them to glance off, preventing severance of major vessels like the carotid arteries.[4] Despite these strengths, gorgets exhibited limitations in comprehensive protection, particularly against blunt trauma from maces or war hammers, which could deform plates and transmit concussive force to underlying tissues, potentially causing internal bruising or fractures without breaching the metal.[28] Earlier designs using leather or mail offered inferior resistance to pointed thrusts compared to solid plate, allowing penetration under sufficient force, while even advanced steel variants contained joints and seams susceptible to exploitation via half-swording or prying weapons.[27] Archaeological examinations of skeletal remains from medieval battle sites reveal instances of perimortem neck vertebral trauma, suggesting that gorgets did not always preclude injury from upward strikes or when dislodged during grappling.[29] Mobility constraints represented another key drawback, as the rigid collar structure impeded full head rotation and lateral tilting, which could compromise situational awareness and evasion in dynamic melee engagements.[4] The added weight—often 1-2 kg depending on size and material—contributed to overall armor fatigue, elevating metabolic demands and hastening exhaustion, though this was mitigated in high-end custom fits prioritizing ergonomic articulation over maximal thickness.[30] Nonetheless, the gorget's integration into the cuirass-helmet ensemble minimized exposure gaps, underscoring its indispensable role in achieving balanced defensive coverage despite inherent trade-offs.[27]Role in Military Uniforms

Transition from Functional Armor to Ornamental Insignia

The gorget's evolution from a protective element of plate armor to an ornamental military insignia occurred primarily during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, coinciding with the obsolescence of full body armor due to the increasing prevalence of firearms, which rendered heavy plate ineffective against musket balls and cannon fire. By the end of the 17th century, the gorget persisted as the sole remnant of knightly armor, retained by officers not for defense but as a symbol of commissioned rank.[2] In European armies, the functional back plate of the gorget was often discarded, leaving the front plate to be worn suspended from a chain or ribbon around the neck, transforming it into a badge of authority displayed only during duty. This shift emphasized decoration over utility, with gorgets crafted from silver or gilt metal, frequently engraved with regimental devices, royal ciphers, or national arms to signify allegiance and status. For instance, in the British Army, purely decorative gorgets emerged in the final years of Charles II's reign (1660–1685), marking the definitive transition to insignia.[11] By the 18th century, gorgets had fully assumed an ornamental role across major European militaries, worn by officers to denote command responsibility and worn suspended rather than fitted as armor. Regulations standardized their use; for example, from 1743 in some forces, they were specified as gilt or silver depending on rank, underscoring their status as non-protective emblems. This ornamental function persisted into the early 19th century, with gorgets abolished in the British Army in 1830 and in the French Army in 1850, after which collar patches evolved as successors.[31]Gorget Patches as Rank Indicators

Gorget patches, consisting of paired cloth or embroidered insignia affixed to the collar of military uniforms, function primarily as visible markers of rank, particularly for senior officers, evolving from the ornamental metal gorgets that served as badges of rank in 18th- and early 19th-century European armies.[6] These patches denote hierarchical status through color, piping, and symbols such as bars, stars, or laurels, allowing rapid identification in command structures without reliance on shoulder epaulettes or sleeve markings. In the British Army, scarlet gorget patches—informally termed "red tabs"—are reserved for general officers, brigadiers, and colonels, signaling their eligibility for staff duties or high-level appointments; this convention originated in the late 19th century with cloth strips on collars designated as gorget patches via an 1896 Army Order, with usage formalized and restricted to full colonels and above by 1921.[8] The design's simplicity and placement on the gorget area preserved the historical association with throat protection while adapting to modern service dress, where they contrast against khaki or blue uniforms to emphasize authority. Commonwealth forces adopted analogous systems, with the Australian Army mandating gorget patches for generals, brigadiers, and colonels to indicate equivalent senior ranks, maintaining the red tab tradition for interoperability with British norms.[8] Similarly, in the Canadian Army during the First and Second World Wars, officers wore gorget patches on the tunic collar as explicit rank or appointment indicators, directly referencing the silver gorgets commissioned officers displayed centuries earlier to affirm commissioned status.[32] This persisted into mid-20th-century regulations, where patches supplemented chevrons or pips for clarity in field conditions.[32] The patches' effectiveness as rank indicators lies in their durability and visibility, though variations exist; for instance, gold-embroidered versions with rank-specific motifs like oak leaves or cyphers appear in some air forces and police units, but their core role remains tied to officer hierarchies rather than enlisted grades.[9] Unlike broader insignia systems, gorget patches prioritize subtlety for formal or staff environments, avoiding the ostentation of full dress epaulettes while ensuring empirical distinguishability grounded in longstanding uniform codes.National Variations in Europe

Across European militaries in the 18th and early 19th centuries, gorgets evolved into standardized crescent-shaped badges of silver or gilt, suspended from neck chains and engraved with regimental motifs, royal cyphers, or national emblems to denote officer rank during ceremonial and field duties.[6] These ornaments varied by nation in design details, such as enamelwork, gilding levels, and inscriptions, reflecting monarchical symbols and uniform regulations, though their core function as vestigial throat protectors transitioned uniformly to insignia by the late 17th century.[33] Adoption was widespread among infantry and cavalry officers, with discontinuation tied to broader uniform reforms favoring embroidered collars or epaulettes.Swedish Military Traditions

Swedish army regulations prescribed gorgets for officers as early as 1688, marking one of the earliest formalized uses in Europe for both rank identification and duty indication.[33][34] Designs featured the reigning monarch's cypher, often in enamel under a crown; for instance, during Gustav III's reign (1771–1792), captains wore gilt versions with palm branches for senior ranks, while ensigns and lieutenants used silver examples bearing the royal initials.[35] By 1799, specialized models like the dagbricka served as duty gorgets for officers of the day, retaining ornamental value post-1792 when general rank usage was phased out in favor of sashes and buttons.[35] Unlike broader European norms, Swedish gorgets emphasized regimental drabants and infantry without sashes, integrating them into Carolean-era uniforms for visibility in linear tactics.[34]Norwegian and Finnish Practices

Norwegian military traditions mirrored Scandinavian neighbors with limited distinct gorget usage, primarily adopting Swedish-influenced designs during the 19th-century union with Sweden, though specific regimental variations remain sparsely documented beyond general officer ornaments. Finnish forces, post-independence in 1917, retained gorgets in ceremonial contexts akin to Swedish precedents, with modern duty officers wearing simplified metal plaques to signify responsibility, echoing historical rank badges from the Grand Duchy era under Russian rule where Swedish-style crescents prevailed until early 20th-century reforms.[36]British and Other Continental Uses

British officers wore engraved silver gorgets until official discontinuation in 1830, exemplified by a 1775–1776 piece for the 60th Regiment featuring beaded rims and crown motifs for parade and campaign identification.[37][6] On the continent, French armies phased them out by 1850, with Prussian and Austrian variants incorporating heraldic eagles or imperial ciphers in gilt for hussar and guard units. German practices revived gorgets selectively in the 20th century, notably for Feldgendarmerie military police during World War II, using luminous eagle-emblazoned crescents for authority assertion in occupied territories.[38] These differences highlight national emphases: Britain's on regimental loyalty, France's on Napoleonic uniformity, and Germany's on functional revival amid total war.[6]Swedish Military Traditions

In the Swedish Army, gorgets known as ringkrage served as distinctive insignia for commissioned officers from the late 17th century, evolving from protective armor into symbols of rank and monarchical allegiance. Early evidence of their use appears in records from Västmanlands regemente in 1624, with formal regulations established by 1688 for infantry officers, mandating crescent-shaped silver plates suspended from the neck.[39] These were polished for lieutenants and ensigns, while captains and higher ranks wore gold-plated versions featuring the crowned royal cypher, often in gold or blue enamel, to signify loyalty to the sovereign.[33] [39] The 1698 ordinance under Charles XII standardized gorgets across infantry units and the Life Guard Drabants, requiring all officers to wear silver examples, with senior ranks gilded and adorned with enamel cyphers; colonels' gorgets included additional motifs like lions or palm branches for hierarchical distinction.[39] Unlike cavalry officers, who employed gold lace instead, infantry and guard officers relied on the gorget as the primary visible rank marker, forgoing the sashes common in other European armies.[39] [34] This practice aligned with the austere yet disciplined Carolean uniform tradition, emphasizing functionality and royal devotion during Sweden's era of great power status. By the late 18th century, gorget use declined; from 1775, they were restricted to battalion command formations, and in 1792, they were fully replaced as rank insignia by epaulettes amid broader uniform reforms.[39] [33] A specialized variant, the dagbricka, persisted from 1799 for the officer of the day, bearing the lesser coat of arms and remaining in ceremonial use into the present.[33]Norwegian and Finnish Practices

In Norwegian military uniforms, gorgets served as distinctive insignia primarily for the officer-of-the-day, a role involving oversight of daily garrison duties and security. Examples from the period 1880–1920 feature silver construction adorned with powdered glass or vitreous enamel, gold accents, metal buckles, and silk elements, reflecting ornamental continuity from earlier European officer traditions.[40] This usage aligned with broader Scandinavian practices during the 19th-century union with Sweden (1814–1905), where such items symbolized authority without functional armor, though specific adoption dates in Norwegian regiments remain sparsely documented beyond artifact evidence. Finnish practices emphasize gorgets for duty roles within the Finnish Defence Forces, extending from historical influences under Swedish rule (until 1809) and Russian autonomy into modern conscript service. Metal gorgets, often silver or gold-colored, mark the duty conscript of a company or the officer of the guard, with elaborate silver variants denoting higher ceremonial responsibilities.[41] This retention follows 20th-century revivals inspired by German military customs during wartime cooperation (1941–1944), prioritizing visibility for command positions over everyday rank insignia like collar patches.[42] Unlike broader gorget patches used for corps affiliation in dress uniforms, these plated versions maintain a direct lineage to 18th-century ornamental badges, underscoring practical signaling in barracks and guard settings.British and Other Continental Uses

In the British Army, gorgets evolved from functional neck armor into purely ornamental badges of rank for officers starting in the 1680s, typically consisting of crescent-shaped silver or gilt plates suspended by a chain around the neck and engraved with regimental devices, royal cyphers, or heraldic motifs such as the royal arms.[11] These items signified commissioned status and were worn with full dress uniforms during the 18th and early 19th centuries, including by officers of regiments like the 60th (Royal American) Regiment in campaigns such as the American Revolutionary War, where examples from 1775–1776 featured detailed engravings.[37] Gorgets were abolished from British officer uniforms in 1830 as part of broader uniform reforms emphasizing practicality over vestigial armor remnants.[6] Across other continental European armies, such as the French and Prussian, gorgets served analogous roles as officer insignia from the late 17th century onward, often mirroring British designs in shape and materials but incorporating national symbols like the Bourbon fleur-de-lis or Hohenzollern eagles.[6] In the French Army, these badges persisted longer, with discontinuation occurring around 1850 following the July Monarchy's uniform standardizations, as evidenced by surviving examples bearing royal arms from the Bourbon era.[43][6] Prussian forces integrated gorgets as formal service badges derived from earlier armored gorgets, worn by infantry and cavalry officers into the 19th century to denote rank and unit affiliation, with continued limited use in the Imperial German Army until 1918.[6] This ornamental tradition underscored hierarchical distinction in line infantry tactics, where visibility of rank was essential for command cohesion on the battlefield.Cultural, Symbolic, and Decorative Uses

Civilian and Fashion Contexts

In medieval Europe, particularly between the 13th and 15th centuries, a gorget denoted a band of linen or fabric wrapped around a woman's neck and often extending to cover the head, functioning as a high collar that concealed the neck, ears, and portions of the hair while integrating with veils or wimples.[44] This garment emphasized modesty, social standing, and regional fashion norms, crafted from materials ranging from coarse linen for everyday wear to fine silks for elite women, and sometimes stiffened or embroidered for decorative effect.[45][46] It represented a precursor to more structured neckwear, bridging practical coverage with aesthetic appeal in civilian attire. By the late 16th and early 17th centuries, metal gorgets—evolving from battlefield armor—entered civilian male fashion as ornamental badges of rank and knighthood, worn openly to signal military commission or noble status outside active duty.[47] These pieces, often gilded or embossed, served ceremonial purposes in social and diplomatic settings, prioritizing display over defense and reflecting a broader trend of militaristic motifs in civilian dress among the European aristocracy.[48] Such usage persisted into the 18th century in select contexts, though it waned with uniform reforms, leaving gorgets as historical curiosities rather than ongoing fashion staples.Pre-Columbian and Native American Artifacts

In indigenous cultures of the Eastern Woodlands of North America, gorgets were ornamental pendants suspended from cords and worn around the neck, often signifying status, spiritual protection, or ceremonial importance. Crafted primarily from marine shells such as whelk or conch obtained via long-distance trade from the Gulf of Mexico, as well as stone or native copper, these artifacts appeared as early as the Archaic period (circa 6000–1000 BCE) and persisted through the Woodland periods into the Mississippian era (circa 1000–1600 CE).[49][50] Early examples, like banded slate gorgets, featured simple drilled perforations for suspension, while later ones incorporated polished surfaces and engravings executed with stone or bone tools.[19] Mississippian gorgets, particularly those from mound-building societies, exemplify advanced artistic expression tied to the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC), a symbolic system flourishing between approximately 1250 and 1450 CE. Engraved motifs commonly depicted raptorial birds, serpents, warriors, or hybrid mythological beings, reflecting cosmological beliefs in power, fertility, and the underworld; for instance, the Four-Crested Bird style on a Tennessee gorget symbolizes interconnected realms of sky, earth, and water in Southeastern worldviews.[51][52] These items, averaging 10–15 cm in length, were frequently interred with high-status individuals, as evidenced by finds at sites like Spiro Mounds in Oklahoma, where conch shell gorgets marked elite graves and indicated influence through rare materials requiring trade networks spanning hundreds of kilometers.[53][54] Pre-Columbian gorgets in Mesoamerican contexts, such as Mayan examples from the Terminal Classic period (circa 830–900 CE), were rarer and typically formed from knapped obsidian or carved shell, serving as elite pendants with potential ritual functions, though documentation remains limited compared to North American variants.[55] In both regions, gorgets' durability and portability facilitated their role in exchange systems, underscoring pre-contact economic and cultural interconnections across the Americas.[56]Ceremonial and Heraldic Significance

In European military customs from the late 17th to early 19th centuries, the gorget transitioned into a ceremonial badge of commissioned rank, worn suspended from a chain or ribbon around the neck during parades, reviews, and formal assemblies to denote authority vested by the sovereign. No longer providing physical protection, these silver or gilt plates symbolized the officer's throat laid bare in service to the crown, a vestigial nod to its armored origins while emphasizing loyalty and command.[8][11] Heraldically, gorgets often featured engraved or enameled royal cyphers, coats of arms, or regimental devices, functioning as personalized emblems of office and affiliation. In the British Army, for instance, they displayed the royal arms until gradual abolition between 1795 and the 1830s, after which their role persisted in some continental forces as markers of distinction in dress uniforms.[11] This decorative heraldry reinforced hierarchical order and monarchical ties during ceremonial contexts. Beyond Europe, gorgets held ceremonial import in intercultural diplomacy, as when colonial powers gifted inscribed silver examples to Native American chiefs to signify alliances and status, worn in tribal ceremonies akin to European practices. These artifacts, produced from the 18th century onward, paralleled military traditions by denoting rank and reciprocity in formal exchanges.[18]Modern and Tactical Applications

Revival in Contemporary Military Gear

Advances in body armor design have prompted the reintroduction of gorget-like components to address vulnerabilities in the neck and upper chest areas, particularly against fragmentation threats prevalent in contemporary conflicts. The U.S. Improved Outer Tactical Vest (IOTV), introduced in the mid-2000s and updated through generations, incorporates optional ballistic neck and collar yoke protectors featuring soft armor inserts for throat and yoke coverage. These components, available in patterns like OCP, attach to the vest to mitigate risks from shrapnel and small arms fragments, reflecting lessons from operations in Iraq and Afghanistan where unprotected necks contributed to casualties.[57][58] Similarly, the U.S. Marine Corps' Modular Tactical Vest (MTV), fielded around 2007, includes modular gorget elements as part of its scalable protection system, allowing soldiers to add neck guards weighing approximately 1-2 pounds for enhanced torso coverage without full rigid plating. This modular approach balances mobility and protection, with the gorget distributing weight to reduce strain during extended wear. In peer-adversary scenarios, such as the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War since 2022, Ukrainian forces have adopted commercial ballistic gorgets like the Dobron Class 1 neck protector, designed for fragmentation resistance up to 9mm velocities, driven by high volumes of drone-delivered munitions and artillery.[59] Private sector innovations further exemplify this revival, with products like the A-21 Gorzhet offering lightweight, ergonomic ballistic modules for 360-degree neck and upper torso shielding using aramid inserts, compatible with various plate carriers. These systems prioritize minimal restriction on head movement while countering secondary blast effects, as seen in evaluations of gaiter-style protectors like the F.R.A.G. Modern Gorget developed in 2014 for blast mitigation. Adoption in high-threat environments underscores a shift toward comprehensive coverage, informed by empirical wound data showing neck injuries comprising up to 10-15% of survivable battlefield trauma in fragmentation-heavy engagements.[60][61][62]Use in Reenactment, Sports, and Collectibles

In historical reenactment, replica gorgets made from 16- or 18-gauge steel are commonly worn to replicate the appearance and function of period armor, particularly for portraying medieval knights, 18th-century officers, or Napoleonic-era soldiers, enhancing authenticity during events like battle simulations or living history demonstrations.[63] These reproductions often feature hinged designs or rolled edges for mobility, allowing participants to engage in mock combats while minimizing injury risks beyond the throat protection.[64] In combat sports such as Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) and Buhurt—a full-contact medieval fighting discipline—modern gorgets serve as essential protective gear, shielding the neck from strikes with blunt weapons like swords or polearms.[65] HEMA practitioners favor lightweight, articulated models from materials like pre-hardened stainless steel (22-gauge) or ABS synthetic for compatibility with fencing masks, emphasizing flexibility and coverage during sparring sessions governed by safety standards from organizations like the Hemaa Alliance.[66][67] Among collectors, both authentic historical gorgets—such as silver-gilt officer badges from 18th-century European armies—and high-fidelity replicas attract enthusiasts for display in private collections or museums focused on military insignia.[68] Replicas, often handmade from 16-gauge steel with polished finishes measuring around 9-11 inches in length, are marketed for their decorative value and historical accuracy, appealing to hobbyists who value them as affordable alternatives to rare originals.[69][70]Additional and Analogous Uses

References in Biology and Natural History

In ornithology, a gorget denotes a distinctive patch of feathers or coloration on the throat of birds, often exhibiting iridescent or vivid hues that serve display functions such as mate attraction or territorial signaling.[71] This term derives from historical armor terminology but applies in biological contexts to describe plumage variations, particularly in species where the gorget contrasts sharply with surrounding feathers due to structural coloration rather than pigmentation.[72] The iridescence arises from microscopic feather structures, including overlapping barbules that refract light wavelengths, producing shimmering effects visible only at specific angles.[71] Hummingbirds (family Trochilidae) exemplify the gorget most prominently, with males typically bearing elaborate throat patches that flash metallic reds, violets, or greens during courtship dives or perching displays. For instance, the male Anna's hummingbird (Calypte anna) features a rose-red gorget extending onto the head, while the Costa's hummingbird (Calypte costae) displays a violet gorget resembling extended mustache-like feathers.[73] These structures consist of flattened, hollow melanin granules stacked in precise layers within feather barbs, creating diffraction gratings that selectively reflect light for dynamic color shifts essential to reproductive success.[74] In natural history observations, such gorgets have been documented aiding species identification and behavioral studies, as their visibility correlates with environmental light conditions and bird orientation.[75] Beyond hummingbirds, gorgets appear in other avian taxa, such as certain sunbirds or birds-of-paradise, where throat patches enhance visual signaling, though less iridescent.[13] In broader natural history, the term occasionally extends to non-avian animals, like colorful throat regions in lizards or amphibians, but remains predominantly ornithological, underscoring evolutionary adaptations for visual communication in diverse ecosystems.[13] Empirical studies emphasize that gorget development is sexually dimorphic, with females often lacking pronounced versions, reflecting sexual selection pressures observed across documented populations.[76]Miscellaneous Historical and Technical Contexts

Medieval gorgets transitioned from flexible chainmail collars to rigid or articulated steel plates by the 14th century, with lames—overlapping segments—riveted for mobility around the neck and shoulders. This construction bridged the helmet and cuirass, using tempered iron or early steel hammered into shape, often with leather padding beneath for comfort and to absorb impacts.[4][27] By the Renaissance, gorgets incorporated decorative elements like etching and gilding alongside functional riveting, with advanced metallurgy enabling thinner yet harder plates resistant to thrusts and slashes. Manufacturing involved forging blanks, dishing via hammering over stakes, and heat-treating for resilience, reflecting tactical shifts toward pike and early firearm defenses.[77][27] In the 17th and 18th centuries, as full plate declined, gorgets evolved into semi-circular front plates of silver or gilt, discarding rear sections for symbolism over protection; British officers formalized this via a 1684 royal warrant specifying wear as a rank badge, typically suspended by chains or ribbons with engraved regimental motifs. Sizes diminished progressively, standardizing to gold or silver per uniform facings, produced through casting, chasing, and enameling for durability and prestige.[11][2][78] Technical adaptations included modular attachments, such as shoulder straps for pauldrons in combat variants or silk linings in ceremonial pieces, ensuring compatibility with evolving uniforms amid gunpowder warfare's reduced armor needs.[79]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Modular_Tactical_Vest_components.jpg