Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Granule cell

View on Wikipedia

The name granule cell has been used for a number of different types of neurons whose only common feature is that they all have very small cell bodies. Granule cells are found within the granular layer of the cerebellum, the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, the superficial layer of the dorsal cochlear nucleus, the olfactory bulb, and the cerebral cortex.

Cerebellar granule cells account for the majority of neurons in the human brain.[1] These granule cells receive excitatory input from mossy fibers originating from pontine nuclei. Cerebellar granule cells project up through the Purkinje layer into the molecular layer where they branch out into parallel fibers that spread through Purkinje cell dendritic arbors. These parallel fibers form thousands of excitatory granule-cell–Purkinje-cell synapses onto the intermediate and distal dendrites of Purkinje cells using glutamate as a neurotransmitter.

Layer 4 granule cells of the cerebral cortex receive inputs from the thalamus and send projections to supragranular layers 2–3, but also to infragranular layers of the cerebral cortex.

Structure

[edit]Granule cells in different brain regions are both functionally and anatomically diverse: the only thing they have in common is smallness. For instance, olfactory bulb granule cells are GABAergic and axonless, while granule cells in the dentate gyrus have glutamatergic projection axons. These two populations of granule cells are also the only major neuronal populations that undergo adult neurogenesis, while cerebellar and cortical granule cells do not. Granule cells (save for those of the olfactory bulb) have a structure typical of a neuron consisting of dendrites, a soma (cell body) and an axon.

Dendrites: Each granule cell has 3 – 4 stubby dendrites which end in a claw. Each of the dendrites are only about 15 μm in length.

Soma: Granule cells all have a small soma diameter of approximately 10 μm.

Axon: Each granule cell sends a single axon onto the Purkinje cell dendritic tree.[citation needed] The axon has an extremely narrow diameter: ½ micrometre.

Synapse: 100–300,000 granule cell axons synapse onto a single Purkinje cell.[citation needed]

The existence of gap junctions between granule cells allows multiple neurons to be coupled to one another, allowing multiple cells to act in synchrony, and allows signalling functions necessary for granule cell development to occur.[2]

Cerebellar granule cell

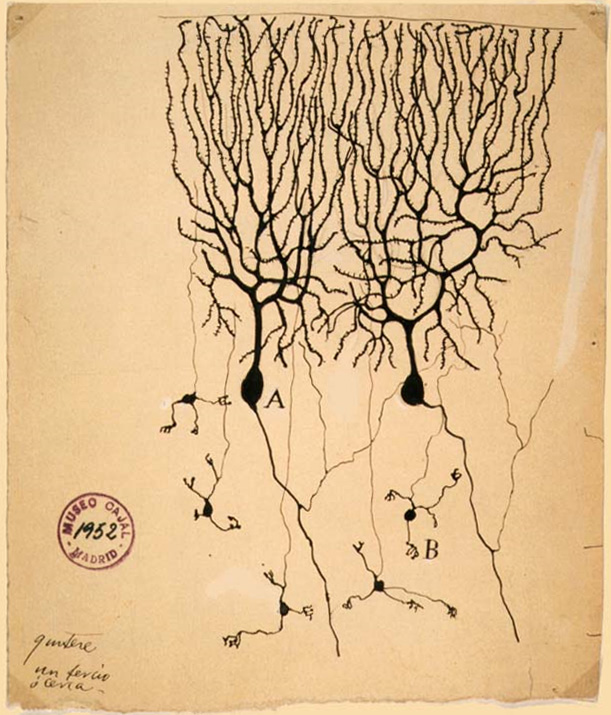

[edit]The granule cells, produced by the rhombic lip, are found in the granule cell layer of the cerebellar cortex. They are small and numerous. They are characterized by a very small soma and several short dendrites which terminate with claw-shaped endings. In the transmission electron microscope, these cells are characterized by a darkly stained nucleus surrounded by a thin rim of cytoplasm. The axon ascends into the molecular layer where it splits to form parallel fibers.[1]

Dentate gyrus granule cell

[edit]The principal cell type of the dentate gyrus is the granule cell. The dentate gyrus granule cell has an elliptical cell body with a width of approximately 10 μm and a height of 18μm.[3]

The granule cell has a characteristic cone-shaped tree of spiny apical dendrites. The dendrite branches project throughout the entire molecular layer, and the furthest tips of the dendritic tree end at the hippocampal fissure or at the ventricular surface.[4] The granule cells are tightly packed in the granular cell layer of the dentate gyrus.

Dorsal cochlear nucleus granule cell

[edit]The granule cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus are small neurons with two or three short dendrites that give rise to a few branches with expansions at the terminals. The dendrites are short with claw-like endings that form glomeruli to receive mossy fibers, similar to cerebellar granule cells.[5] Its axon projects to the molecular layer of the dorsal cochlear nucleus where it forms parallel fibers, also similar to cerebellar granule cells.[6] The dorsal cochlear granule cells are small excitatory interneurons which are developmentally related and thus resemble the cerebellar granule cell.

Olfactory bulb granule cell

[edit]The main intrinsic granule cell in the vertebrate olfactory bulb lacks an axon (as does the accessory neuron). Each cell gives rise to short central dendrites and a single long apical dendrite that expands into the granule cell layer and enters the mitral cell body layer. The dendrite branches terminate within the outer plexiform layer among the dendrites in the olfactory tract.[7] In the mammalian olfactory bulb, granule cells can process both synaptic input and output due to the presence of large spines.[8]

Function

[edit]Neural pathways and circuits of the cerebellum

[edit]

Cerebellar granule cells receive excitatory input from 3 or 4 mossy fibers originating from pontine nuclei. Mossy fibers make an excitatory connection onto granule cells, which causes the granule cells to fire an action potential.

The axon of a cerebellar granule cell splits to form a parallel fiber which innervates Purkinje cells. The vast majority of granule cell axonal synapses are found on the parallel fibers.[9]

The parallel fibers are sent up through the Purkinje layer into the molecular layer where they branch out and spread through Purkinje cell dendritic arbors. These parallel fibers form thousands of excitatory Granule-cell-Purkinje-cell synapses onto the dendrites of Purkinje cells.

This connection is excitatory as glutamate is released.

The parallel fibers and ascending axon synapses from the same granule cell fire in synchrony which results in excitatory signals. In the cerebellar cortex there are a variety of inhibitory neurons (interneurons). The only excitatory neurons present in the cerebellar cortex are granule cells.[10]

Plasticity of the synapse between a parallel fiber and a Purkinje cell is believed to be important for motor learning.[11] The function of cerebellar circuits is entirely dependent on processes carried out by the granular layer. Therefore, the function of granule cells determines the cerebellar function as a whole.[12]

Mossy fiber input on cerebellar granule cells

[edit]Granule cell dendrites also synapse with distinctive unmyelinated axons which Santiago Ramón y Cajal called mossy fibers[4] Mossy fibers and golgi cells both make synaptic connections with granule cells. Together these cells form the glomeruli.[10]

Granule cells are subject to feed-forward inhibition: granule cells excite Purkinje cells but also excite GABAergic interneurons that inhibit Purkinje cells.

Granule cells are also subject to feedback inhibition: Golgi cells receive excitatory stimuli from granule cells and in turn send back inhibitory signals to the granule cell.[13]

Mossy fiber input codes are conserved during synaptic transmission between granule cells, suggesting that innervation is specific to the input that is received.[14] Granule cells do not just relay signals from mossy fibers, rather they perform various, intricate transformations which are required in the spatiotemporal domain.[10]

Each granule cell is receiving an input from two different mossy fiber inputs. The input is thus coming from two different places as opposed to the granule cell receiving multiple inputs from the same source.

The differences in mossy fibers that are sending signals to the granule cells directly effects the type of information that granule cells translate to Purkinje cells. The reliability of this translation will depend on the reliability of synaptic activity in granule cells and on the nature of the stimulus being received.[15] The signal a granule cell receives from a Mossy fiber depends on the function of the mossy fiber itself. Therefore, granule cells are able to integrate information from the different mossy fibers and generate new patterns of activity.[15]

Climbing fiber input on cerebellar granule cells

[edit]Different patterns of mossy fiber input will produce unique patterns of activity in granule cells that can be modified by a teaching signal conveyed by the climbing fiber input. David Marr and James Albus suggested that the cerebellum operates as an adaptive filter, altering motor behaviour based on the nature of the sensory input.

Since multiple (~200,000) granule cells synapse onto a single Purkinje cell, the effects of each parallel fiber can be altered in response to a “teacher signal” from the climbing fiber input.

Specific functions of different granule cells

[edit]- Cerebellum granule cells

David Marr suggested that the granule cells encode combinations of mossy fiber inputs. In order for the granule cell to respond, it needs to receive active inputs from multiple mossy fibers. The combination of multiple inputs results in the cerebellum being able to make more precise distinctions between input patterns than a single mossy fiber would allow.[16] The cerebellar granule cells also play a role in orchestrating the tonic conductances which control sleep in conjunction with the ambient levels of GABA which are found in the brain.

- Dentate granule cells

Loss of dentate gyrus neurons from the hippocampus results in spatial memory deficits. Therefore, dentate granule cells are thought to function in the formation of spatial memories [17] and of episodic memories.[18] Immature and mature dentate granule cells have distinct roles in memory function. Adult-born granule cells are thought to be involved in pattern separation whereas old granule cells contribute to rapid pattern completion.[19]

- Dorsal cochlear granule cells

Pyramidal cells from the primary auditory cortex project directly on to the cochlear nucleus. This is important in the acoustic startle reflex, in which the pyramidal cells modulate the secondary orientation reflex and the granule cell input is responsible for appropriate orientation.[20] This is because the signals received by the granule cells contain information about the head position. Granule cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus play a role in the perception and response to sounds in our environment.

- Olfactory bulb granule cells

Inhibition generated by granule cells, the most common GABAergic cell type in the olfactory bulb, plays a critical role in shaping the output of the olfactory bulb.[21] There are two types of excitatory inputs received by GABAergic granule cells; those activated by an AMPA receptor and those activated by a NMDA receptor. This allows the granule cells to regulate the processing of the sensory input in the olfactory bulb.[21] The olfactory bulb transmits smell information from the nose to the brain, and is thus necessary for a proper sense of smell. Granule cells in the olfactory bulb have also been found to be important in forming memories linked with scents.[22]

Critical factors for function

[edit]- Calcium

Calcium dynamics are essential for several functions of granule cells such as changing membrane potential, synaptic plasticity, apoptosis, and regulation of gene transcription.[10] The nature of the calcium signals that control the presynaptic and postsynaptic function of the olfactory bulb granule cells spines is mostly unknown.[8]

- Nitric oxide

Granule neurons have high levels of the neuronal isoform of nitric oxide synthase. This enzyme is dependent on the presence of calcium and is responsible for the production of nitric oxide (NO). This neurotransmitter is a negative regulator of granule cell precursor proliferation which promotes the differentiation of different granule cells. NO regulates interactions between granule cells and glia[10] and is essential for protecting the granule cells from damage. NO is also responsible for neuroplasticity and motor learning.[23]

Role in disease

[edit]Altered morphology of dentate granule cells

[edit]TrkB is responsible for the maintenance of normal synaptic connectivity of the dentate granule cells. TrkB also regulates the specific morphology (biology) of the granule cells and is thus said to be important in regulating neuronal development, neuronal plasticity, learning, and the development of epilepsy.[24] The TrkB regulation of granule cells is important in preventing memory deficits and limbic epilepsy. This is due to the fact that dentate granule cells play a critical role in the function of the entorhinal-hippocampal circuitry in health and disease. Dentate granule cells are situated to regulate the flow of information into the hippocampus, a structure required for normal learning and memory.[24]

Decreased granule cell neurogenesis

[edit]Both epilepsy and depression show a disrupted production of adult-born hippocampal granule cells.[25] Epilepsy is associated with increased production - but aberrant integration - of new cells early in the disease and decreased production late in the disease.[25] Aberrant integration of adult-generated cells during the development of epilepsy may impair the ability of the dentate gyrus to prevent excess excitatory activity from reaching hippocampal pyramidal cells, thereby promoting seizures.[25] Long-lasting epileptic seizure stimulate dentate granule cell neurogenesis. These newly born dentate granule cells may result in aberrant connections that result in the hippocampal network plasticity associated with epileptogenesis.[26]

Shorter granule cell dendrites

[edit]Patients with Alzheimer's have shorter granule cell dendrites. Furthermore, the dendrites were less branched and had fewer spines than those in patients not with Alzheimer's.[27] However, granule cell dendrites are not an essential component of senile plaques and these plaques have no direct effect on granule cells in the dentate gyrus. The specific neurofibrillary changes of dentate granule cells occur in patients with Alzheimer's, Lewy body variant and progressive supranuclear palsy.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Llinás, Rodolfo; Walton, Kerry; Lang, Eric (2004). "Chapter 7: Cerebellum". In Shepherd, Gordon (ed.). The synaptic organization of the brain. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 271–309. ISBN 9780195159561.

- ^ C. Reyher; J Liibke; W Larsen; G Hendrix; M Shipley; H Baumgarten (1991). "Olfactory Bulb Granule Cell Aggregates: Morphological Evidence for lnterperikaryal [sic] Electrotonic Coupling via Gap Junctions" (PDF). The Journal of Neuroscience. 11 (6): 1465–495. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01485.1991. PMC 6575397. PMID 1904478. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Claiborne BJ, Amaral DG, Cowan WM (1990). "A quantitative three-dimensional analysis of granule cell dendrites in the rat dentate gyrus". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 302 (2): 206–219. doi:10.1002/cne.903020203. PMID 2289972. S2CID 1841245.

- ^ a b David G. Amaral; Helen E. Scharfman; Pierre Lavenex (2007). "The dentate gyrus: Fundamental neuroanatomical organization (Dentate gyrus for dummies)". The Dentate Gyrus: A Comprehensive Guide to Structure, Function, and Clinical Implications. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 163. pp. 3–22. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5. ISBN 978-0-444-53015-8. PMC 2492885. PMID 17765709.

- ^ Mugnaini E, Osen KK, Dahl AL, Friedrich VL Jr, Korte G (1980). "Fine structure of granule cells and related interneurons (termed Golgi cells) in the cochlear nuclear complex of cat, rat and mouse". Journal of Neurocytology. 9 (4): 537–70. doi:10.1007/BF01204841. PMID 7441303. S2CID 19588537.

- ^ Young, Eric; Oertel, Donata (2004). "Chapter 4: Cochlear Nucleus". In Shepherd, Gordon (ed.). The synaptic organization of the brain. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 125–163. ISBN 9780195159561.

- ^ Neville, Kevin; Haberly, Lewis (2004). "Chapter 10: Olfactory Cortex". In Shepherd, Gordon (ed.). The synaptic organization of the brain. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 415–453. ISBN 9780195159561.

- ^ a b V Egger; K Svoboda; Z Mainen (2005). "Dendrodendritic Synaptic Signals in Olfactory Bulb Granule Cells: Local Spine Boost and Global Low-Threshold Spike". The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (14): 3521–3530. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4746-04.2005. PMC 6725376. PMID 15814782.

- ^ Huang CM, Wang L, Huang RH (2006). "Cerebellar granule cell: ascending axon and parallel fiber". European Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (7): 1731–1737. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04690.x. PMID 16623829. S2CID 19270731.

- ^ a b c d e M Manto; C De Zeeuw (2012). "Diversity and Complexity of Roles of Granule Cells in the Cerebellar Cortex". The Cerebellum. 11 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1007/s12311-012-0365-7. PMID 22396329. S2CID 7270048.

- ^ M. Bear; M. Paradiso (2006). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 855. ISBN 9780781760034.

- ^ P. Seja; M. Schonewille; G. Spitzmaul; A. Badura; I. Klein; Y. Rudhard; W. Wisden; C.A. Hübner; C.I. De Zeeuw; T.J. Jentsch (Mar 7, 2012). "Raising cytosolic Cl(-) in cerebellar granule cells affects their excitability and vestibulo-ocular learning". The EMBO Journal. 31 (5): 1217–30. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.488. PMC 3297995. PMID 22252133.

- ^ Eccles JC, Ito M, Szentagothai J (1967). The cerebellum as a neural machine. Springer-Verlag. p. 56. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-13147-3. ISBN 978-3-662-13149-7. S2CID 20690516.

- ^ Bengtssona, F; Jörntell, H (2009). "Sensory transmission in cerebellar granule cells relies on similarly coded mossy fiber inputs". PNAS. 106 (7): 2389–2394. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.2389B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808428106. PMC 2650166. PMID 19164536.

- ^ a b A Arenz; E Bracey; T Margrie (2009). "Sensory representations in cerebellar granule cells". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 19 (4): 445–451. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2009.07.003. PMID 19651506. S2CID 30942776.

- ^ Marr D (1969). "A theory of cerebellar cortex". The Journal of Physiology. 202 (2): 437–70. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008820. PMC 1351491. PMID 5784296.

- ^ M Colicos; P Dash (1996). "Apoptotic morphology of dentate gyrus granule cells following experimental cortical impact injury in rats: possible role in spatial memory deficits". Brain Research. 739 (1–2): 120–131. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(96)00824-4. PMID 8955932. S2CID 26445302.

- ^ Kovács KA (September 2020). "Episodic Memories: How do the Hippocampus and the Entorhinal Ring Attractors Cooperate to Create Them?". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 14: 68. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2020.559186. PMC 7511719. PMID 33013334.

- ^ T Nakashiba; J Cushman; K Pelkey; S Renaudineau; D Buhl; T McHugh; V Rodriguez Barrera; R Chittajallu; K Iwamoto; C McBain; M Fanselow; S Tonegawa (2012). "Young Dentate Granule Cells Mediate Pattern Separation, whereas Old Granule Cells Facilitate Pattern Completion". Cell. 149 (1): 188–201. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.046. PMC 3319279. PMID 22365813.

- ^ Weedman DL, Ryugo DK (1996). "Projections from auditory cortex to the cochlear nucleus in rats: synapses on granule cell dendrites". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 371 (2): 311–324. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960722)371:2<311::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 8835735. S2CID 18382868.

- ^ a b R Balu; R Pressler; B Strowbridge (2007). "Multiple Modes of Synaptic Excitation of Olfactory Bulb Granule Cells". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (21): 5621–5632. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4630-06.2007. PMC 6672747. PMID 17522307.

- ^ Jansen, Jaclyn. "First glimpse of brain circuit that helps experience to shape perception". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ R Feil; J Hartmann; C Luo; W Wolfsgruber; K Schilling; S Feil; et al. (2003). "Impairment of LTD and cerebellar learning by Purkinje cell specific ablation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I." The Journal of Cell Biology. 163 (2): 295–302. doi:10.1083/jcb.200306148. PMC 2173527. PMID 14568994.

- ^ a b S Danzer; R Kotloski; C Walter; Maya Hughes; J McNamara (2008). "Altered morphology of hippocampal dentate granule cell presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals following conditional deletion of TrkB". Hippocampus. 18 (7): 668–678. doi:10.1002/hipo.20426. PMC 3377475. PMID 18398849.

- ^ a b c S Danzer (2012). "Depression, stress, epilepsy and adult neurogenesis". Experimental Neurology. 233 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.023. PMC 3199026. PMID 21684275.

- ^ J. Parent; T Yu; R Leibowitz; D Geschwind; R Sloviter; D Lowenstein (1997). "Dentate Granule Cell Neurogenesis Is Increased by Seizures and Contributes to Aberrant Network Reorganization in the Adult Rat Hippocampus". The Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (10): 3727–3738. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03727.1997. PMC 6573703. PMID 9133393.

- ^ Einstein G, Buranosky R, Crain BJ (1994). "Dendritic pathology of granule cells in Alzheimer's disease is unrelated to neuritic plaques". The Journal of Neuroscience. 14 (8): 5077–5088. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-05077.1994. PMC 6577187. PMID 8046469.

- ^ Wakabayashi K, Hansen LA, Vincent I, Mallory M, Masliah E (1997). "Neurofibrillary tangles in the dentate granule cells of patients with Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body disease and progressive supranuclear palsy". Acta Neuropathologica. 93 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1007/s004010050576. PMID 9006651. S2CID 10136450.