Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dendrite

View on Wikipedia

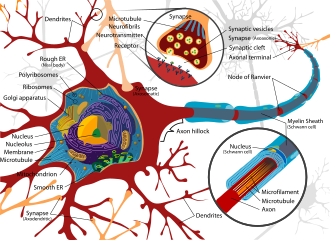

A dendrite (from Greek δένδρον déndron, "tree") or dendron is a branched cytoplasmic process that extends from a nerve cell that propagates the electrochemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body, or soma, of the neuron from which the dendrites project. Electrical stimulation is transmitted onto dendrites by upstream neurons (usually via their axons) via synapses which are located at various points throughout the dendritic tree.

Dendrites play a critical role in integrating these synaptic inputs and in determining the extent to which action potentials are produced by the neuron.[1]

Structure and function

[edit]

Dendrites are one of two types of cytoplasmic processes that extrude from the cell body of a neuron, the other type being an axon. Axons can be distinguished from dendrites by several features including shape, length, and function. Dendrites often taper off in shape and are shorter, while axons tend to maintain a constant radius and can be very long. Typically, axons transmit electrochemical signals and dendrites receive the electrochemical signals, although some types of neurons in certain species lack specialized axons and transmit signals via their dendrites.[3] Dendrites provide an enlarged surface area to receive signals from axon terminals of other neurons.[4] The dendrite of a large pyramidal cell receives signals from about 30,000 presynaptic neurons.[5] Excitatory synapses terminate on dendritic spines, tiny protrusions from the dendrite with a high density of neurotransmitter receptors. Most inhibitory synapses directly contact the dendritic shaft.

Synaptic activity causes local changes in the electrical potential across the plasma membrane of the dendrite. This change in membrane potential will passively spread along the dendrite, but becomes weaker with distance without an action potential. To generate an action potential, many excitatory synapses have to be active at the same time, leading to strong depolarization of the dendrite and the cell body (soma). The action potential, which typically starts at the axon hillock, propagates down the length of the axon to the axon terminals where it triggers the release of neurotransmitters, but also backwards into the dendrite (retrograde propagation), providing an important signal for spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP).[4]

Most synapses are axodendritic, involving an axon signaling to a dendrite. There are also dendrodendritic synapses, signaling from one dendrite to another.[6] An autapse is a synapse in which the axon of one neuron transmits signals to its own dendrite.

The general structure of the dendrite is used to classify neurons into multipolar, bipolar and unipolar types. Multipolar neurons are composed of one axon and many dendritic trees. Pyramidal cells are multipolar cortical neurons with pyramid-shaped cell bodies and large dendrites that extend towards the surface of the cortex (apical dendrite). Bipolar neurons have two main dendrites at opposing ends of the cell body. Many inhibitory neurons have this morphology. Unipolar neurons, typical for insects, have a stalk that extends from the cell body that separates into two branches with one containing the dendrites and the other with the terminal buttons. In vertebrates, sensory neurons detecting touch or temperature are unipolar.[6][7][8] Dendritic branching can be extensive and in some cases is sufficient to receive as many as 100,000 inputs to a single neuron.[4]

History

[edit]The term dendrites was first used in 1889 by Wilhelm His to describe the number of smaller "protoplasmic processes" that were attached to a nerve cell.[9] German anatomist Otto Friedrich Karl Deiters is generally credited with the discovery of the axon by distinguishing it from the dendrites.

Some of the first intracellular recordings in a nervous system were made in the late 1930s by Kenneth S. Cole and Howard J. Curtis. Swiss Rüdolf Albert von Kölliker and German Robert Remak were the first to identify and characterize the axonal initial segment. Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley also employed the squid giant axon (1939) and by 1952 they had obtained a full quantitative description of the ionic basis of the action potential, leading to the formulation of the Hodgkin–Huxley model. Hodgkin and Huxley were awarded jointly the Nobel Prize for this work in 1963. The formulas detailing axonal conductance were extended to vertebrates in the Frankenhaeuser–Huxley equations. Louis-Antoine Ranvier was the first to describe the gaps or nodes found on axons and for this contribution these axonal features are now commonly referred to as the Nodes of Ranvier. Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a Spanish anatomist, proposed that axons were the output components of neurons.[10] He also proposed that neurons were discrete cells that communicated with each other via specialized junctions, or spaces, between cells, now known as a synapse. Ramón y Cajal improved a silver staining process known as Golgi's method, which had been developed by his rival, Camillo Golgi.[11]

Dendrite development

[edit]

During the development of dendrites, several factors can influence differentiation. These include modulation of sensory input, environmental pollutants, body temperature, and drug use.[12] For example, rats raised in dark environments were found to have a reduced number of spines in pyramidal cells located in the primary visual cortex and a marked change in distribution of dendrite branching in layer 4 stellate cells.[13] Experiments done in vitro and in vivo have shown that the presence of afferents and input activity per se can modulate the patterns in which dendrites differentiate.[14]

Little is known about the process by which dendrites orient themselves in vivo and are compelled to create the intricate branching pattern unique to each specific neuronal class. One theory on the mechanism of dendritic arbor development is the synaptotropic hypothesis. The synaptotropic hypothesis proposes that input from a presynaptic to a postsynaptic cell (and maturation of excitatory synaptic inputs) eventually can change the course of synapse formation at dendritic and axonal arbors.[15][16]

This synapse formation is required for the development of neuronal structure in the functioning brain. A balance between metabolic costs of dendritic elaboration and the need to cover the receptive field presumably determine the size and shape of dendrites. A complex array of extracellular and intracellular cues modulates dendrite development including transcription factors, receptor-ligand interactions, various signaling pathways, local translational machinery, cytoskeletal elements, Golgi outposts and endosomes. These contribute to the organization of the dendrites on individual cell bodies and the placement of these dendrites in the neuronal circuitry. For example, it was shown that β-actin zipcode binding protein 1 (ZBP1) contributes to proper dendritic branching.[citation needed]

Other important transcription factors involved in the morphology of dendrites include CUT, Abrupt, Collier, Spineless, ACJ6/drifter, CREST, NEUROD1, CREB, NEUROG2 etc. Secreted proteins and cell surface receptors include neurotrophins and tyrosine kinase receptors, BMP7, Wnt/dishevelled, EPHB 1–3, Semaphorin/plexin-neuropilin, slit-robo, netrin-frazzled, reelin. Rac, CDC42 and RhoA serve as cytoskeletal regulators, and the motor protein includes KIF5, dynein, LIS1.[citation needed] Dendritic arborization has been found to be induced in cerebellum Purkinje cells by substance P.[17] Important secretory and endocytic pathways controlling the dendritic development include DAR3 /SAR1, DAR2/Sec23, DAR6/Rab1 etc.[citation needed] All these molecules interplay with each other in controlling dendritic morphogenesis including the acquisition of type specific dendritic arborization, the regulation of dendrite size and the organization of dendrites emanating from different neurons.[1][18]

Types of dendritic patterns

[edit]Dendritic arborization, also known as dendritic branching, is a multi-step biological process by which neurons form new dendritic trees and branches to create new synapses.[1] Dendrites in many organisms assume different morphological patterns of branching. The morphology of dendrites such as branch density and grouping patterns are highly correlated to the function of the neuron. Malformation of dendrites is also tightly correlated to impaired nervous system function.[14]

Branching morphologies may assume an adendritic structure (not having a branching structure, or not tree-like), or a tree-like radiation structure.[citation needed] Tree-like arborization patterns can be spindled (where two dendrites radiate from opposite poles of a cell body with few branches, see bipolar neurons ), spherical (where dendrites radiate in a part or in all directions from a cell body, see cerebellar granule cells), laminar (where dendrites can either radiate planarly, offset from cell body by one or more stems, or multi-planarly, see retinal horizontal cells, retinal ganglion cells, retinal amacrine cells respectively), cylindrical (where dendrites radiate in all directions in a cylinder, disk-like fashion, see pallidal neurons), conical (dendrites radiate like a cone away from cell body, see pyramidal cells), or fanned (where dendrites radiate like a flat fan as in Purkinje cells).

Electrical properties

[edit]The structure and branching of a neuron's dendrites, as well as the availability and variation of voltage-gated ion conductance, strongly influences how the neuron integrates the input from other neurons. This integration is both temporal, involving the summation of stimuli that arrive in rapid succession, as well as spatial, entailing the aggregation of excitatory and inhibitory inputs from separate branches.[19]

Dendrites were once thought to merely convey electrical stimulation passively. This passive transmission means that voltage changes measured at the cell body are the result of activation of distal synapses propagating the electric signal towards the cell body without the aid of voltage-gated ion channels. Passive cable theory describes how voltage changes at a particular location on a dendrite transmit this electrical signal through a system of converging dendrite segments of different diameters, lengths, and electrical properties. Based on passive cable theory one can track how changes in a neuron's dendritic morphology impact the membrane voltage at the cell body, and thus how variation in dendrite architectures affects the overall output characteristics of the neuron. Dendrite radius has notable effects on resistance to electrical current, which in turn affects conduction time and speed. Dendrite branching optimizes of energy efficiency while maintaining functional connectivity by minimizing power and emphasizing effective signal transmission, supporting their roles in signal integration over longer times. This behavior seen in dendrites differs from that in axons, which give more priority to conduction time (and speed). Such tradeoffs influence overall neuronal structures, leading to a scaling relationship between conduction time and body size.[20][21][22]

Action potentials initiated at the axon hillock propagate back into the dendritic arbor. These back-propagating action potentials depolarize the dendritic membrane and provide a crucial signal for synapse modulation and long-term potentiation. Back-propagation is not completely passive, but modulated by the presence of dendritic voltage-gated potassium channels. Furthermore, in certain types of neurons, a train of back-propagating action potentials can induce a calcium action potential (a dendritic spike) at dendritic initiation zones.[23][24]

Neurotransmitter release

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

Dendrites release a multitude of neuroactive substances that are not confined to specific neurotransmitter class, signaling molecule, or brain area. Dendrites are seen releasing neurotransmitters such as dopamine, GABA and glutamate in a retrograde fashion. In the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial peptide system, oxytocin and vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone or ADH), are notable neuropeptides that are released from the dendrites of magnocellular neurosecretory cells (MCNs), allowing them to quickly enter the bloodstream. Paraventricular nuclei also release oxytocin and ADH from dendrites, allowing for the regulation of the anterior pituitary gland, as well as modulation of the parasympathetic and sympathetic changes in organs such as the heart and kidneys; this is done by Parvocellular neurosecretory and Parvocellular preautonomic neurons, respectively. In the nigrostriatal and mesolimbic systems, dopamine is released from dendrites in midbrain dopamine neurons, influencing reward and emotion processing, as well as learning and memory. Loss of dopamine from in the nigrostriatal pathway affects neuronal activity from the basal ganglia, therefore playing a role in the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's. Dendritic release of oxytocin, ADH and dopamine have been found to have both autocrine and paracrine effects on the neuron itself (and nearby glia), as well as on afferent nerve terminals.[25]

Plasticity

[edit]Dendrites themselves appear to be capable of plastic changes during the adult life of animals, including invertebrates.[26] Neuronal dendrites have various compartments known as functional units that are able to compute incoming stimuli. These functional units are involved in processing input and are composed of the subdomains of dendrites such as spines, branches, or groupings of branches. Therefore, plasticity that leads to changes in the dendrite structure will affect communication and processing in the cell. During development, dendrite morphology is shaped by intrinsic programs within the cell's genome and extrinsic factors such as signals from other cells. But in adult life, extrinsic signals become more influential and cause more significant changes in dendrite structure compared to intrinsic signals during development. In females, the dendritic structure can change as a result of physiological conditions induced by hormones during periods such as pregnancy, lactation, and following the estrous cycle. This is particularly visible in pyramidal cells of the CA1 region of the hippocampus, where the density of dendrites can vary up to 30%.[14]

Recent experimental observations suggest that adaptation is performed in the neuronal dendritic trees, where the timescale of adaptation was observed to be as low as several seconds.[27][28] Certain machine learning architectures based on dendritic trees have been shown to simplify the learning algorithm without affecting performance.[29]

Other functions and properties

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

Most excitatory neurons receive synaptic inputs across their dendritic branches, which results in electrical and biochemical compartmentalization, allowing for a phenomenon known as dendritic spikes, where local regenerative potentials contribute to plasticity. In pyramidal neurons dendritic trees have two main functions that allow them to demonstrate an electrical and biochemical compartmentalization that may integrate synaptic inputs prior to transmission to the soma, as well as make up computation units in the brain. The first main function allows for differential synaptic processing due to distribution of synaptic inputs across the dendritic branches. The processing of these synaptic inputs often involve feedforward or feedback mechanisms that vary based on the type of neuron or brain region. The opposite but combined functions of feedforward and feedback processes at different times is proposed to associate different information streams that determine neural selectivity to different stimuli.

The second function of dendritic trees in this regard is their ability to shape signal propagation that allows for sub-cellular compartmentalization. Large depolarizations can lead to local regenerative potentials, which may allow neurons to transition from stages of isolated dendritic events (segregation) to combined dendritic events (integration). Dendritic compartmentalization has implications in information processing, where it serves as a foundation of trans-neuron signaling, processing stimuli, computation, neuronal expressivity, and mitigating neuronal noise. Likewise, this phenomenon also underlies the storage of information by optimizing learning capacity and storage capacity. In other types of neurons, such as those of the medial superior olive, have differing dendritic properties that allow for coincidence detection. In contrast, in retinal ganglion cells, dendritic integration is used for computing directional selectivity, allowing neurons to respond to direction of movement. Therefore dendritic trees serve various purposes in integrating and processing various different types of stimuli and underly various neurological processes.[30]

Clinical implications of dysfunction

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

Dendrite dysfunction and alterations in dendrite morphology may contribute to many neuropathies and diseases. Changes in dendrite morphology may include alterations in branching patterns, fragmentation, loss of branching, and alterations in spine morphology and number. Such abnormalities contribute to a wide range of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders such as autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), schizophrenia, down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, Alzheimer's disease (AD), and more. For example, subjects with ASD were observed to have reduced dendrite branching in the CA1 and CA4 regions of the hippocampus, in addition to increased spine density. In Rett Syndrome, researchers have observed less dendrite branching in the basal dendrites of the motor cortex and subiculum. In schizophrenic patients, reduced dendritic arbor (the tree-like network of dendrites) and spine density were observed. In addition to psychological and neurodevelopmental disorders, dendrite dysfunction has also been seen to have implications in onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's. Alzheimer's patients have been observed to have significant changes in dendritic arbor, as well as smaller dendrite lengths in the apical and basal trees of the CA1a and CA1b areas of the hippocampus. As such, there is much continuous research exploring the effects of dysfunction in dendritic branching and morphology, and scientists continue to expand their study in this field to better understand the basis of various neurological disorders.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Urbanska M, Blazejczyk M, Jaworski J (2008). "Molecular basis of dendritic arborization". Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis. 68 (2): 264–288. doi:10.55782/ane-2008-1695. PMID 18511961.

- ^ Perez-Alvarez, Alberto; Fearey, Brenna C.; O’Toole, Ryan J.; Yang, Wei; Arganda-Carreras, Ignacio; Lamothe-Molina, Paul J.; Moeyaert, Benjamien; Mohr, Manuel A.; Panzera, Lauren C.; Schulze, Christian; Schreiter, Eric R.; Wiegert, J. Simon; Gee, Christine E.; Hoppa, Michael B.; Oertner, Thomas G. (2020-05-18). "Freeze-frame imaging of synaptic activity using SynTagMA". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 2464. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.2464P. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16315-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7235013. PMID 32424147.

- ^ Yau KW (December 1976). "Receptive fields, geometry and conduction block of sensory neurones in the central nervous system of the leech". The Journal of Physiology. 263 (3): 513–538. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011643. PMC 1307715. PMID 1018277.

- ^ a b c Alberts B (2009). Essential Cell Biology (3rd ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4129-1.

- ^ Eyal, Guy; Verhoog, Matthijs B.; Testa-Silva, Guilherme; Deitcher, Yair; Benavides-Piccione, Ruth; DeFelipe, Javier; de Kock, Christiaan P. J.; Mansvelder, Huibert D.; Segev, Idan (2018-06-29). "Human Cortical Pyramidal Neurons: From Spines to Spikes via Models". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 12 181. doi:10.3389/fncel.2018.00181. ISSN 1662-5102. PMC 6034553. PMID 30008663.

- ^ a b Carlson NR (2013). Physiology of Behavior (11th ed.). Boston: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-205-23939-9.

- ^ Pinel JP (2011). Biopsychology (8th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-83256-9.

- ^ Jan YN, Jan LY (May 2010). "Branching out: mechanisms of dendritic arborization". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 11 (5): 316–328. doi:10.1038/nrn2836. PMC 3079328. PMID 20404840.

- ^ Finger S (1994). Origins of neuroscience : a history of explorations into brain function. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780195146943. OCLC 27151391.

The nerve cell with its uninterrupted processes was described by Otto Friedrich Karl Deiters (1834-1863) in a work that was completed by Max Schultze (1825-1874) in 1865, two years after Deiters died of typhoid fever. This work portrayed the cell body with a single chief "axis cylinder" and a number of smaller "protoplasmic processes" (see figure 3.19). The latter would become known as "dendrites", a term coined by Wilhelm His (1831-1904) in 1889.

- ^ Debanne D, Campanac E, Bialowas A, Carlier E, Alcaraz G (April 2011). "Axon physiology" (PDF). Physiological Reviews. 91 (2): 555–602. doi:10.1152/physrev.00048.2009. PMID 21527732. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-05.

- ^ López-Muñoz F, Boya J, Alamo C (October 2006). "Neuron theory, the cornerstone of neuroscience, on the centenary of the Nobel Prize award to Santiago Ramón y Cajal". Brain Research Bulletin. 70 (4–6): 391–405. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.07.010. PMID 17027775. S2CID 11273256.

- ^ McEwen BS (September 2010). "Stress, sex, and neural adaptation to a changing environment: mechanisms of neuronal remodeling". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1204 (Suppl): E38 – E59. Bibcode:2010NYASA1204...38M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05568.x. PMC 2946089. PMID 20840167.

- ^ Borges S, Berry M (July 1978). "The effects of dark rearing on the development of the visual cortex of the rat". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 180 (2): 277–300. doi:10.1002/cne.901800207. PMID 659662. S2CID 42749947.

- ^ a b c Tavosanis G (January 2012). "Dendritic structural plasticity". Developmental Neurobiology. 72 (1): 73–86. doi:10.1002/dneu.20951. PMID 21761575. S2CID 2055017.

- ^ Vaughn, James E.; Barber, Robert P.; Sims, Terry J. (1988). "Dendritic development and preferential growth into synaptogenic fields: A quantitative study of Golgi-impregnated spinal motor neurons". Synapse. 2 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1002/syn.890020110. PMID 2458630. S2CID 31184444.

- ^ Cline H, Haas K (March 2008). "The regulation of dendritic arbor development and plasticity by glutamatergic synaptic input: a review of the synaptotrophic hypothesis". The Journal of Physiology. 586 (6): 1509–1517. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150029. PMC 2375708. PMID 18202093.

- ^ Baloyannis, Stavros; Costa, Vassiliki; Deretzi, Georgia; Michmizos, Dimitrios (1999). ""Intraventricular Administration of Substance P Increases the Dendritic Arborisation and the Synaptic Surfaces of Purkinje Cells in Rat's Cerebellum"". International Journal of Neuroscience. 101 (1–4): 89–107. doi:10.3109/00207450008986495. PMID 10765993 – via Pub Med.

- ^ Perycz M, Urbanska AS, Krawczyk PS, Parobczak K, Jaworski J (April 2011). "Zipcode binding protein 1 regulates the development of dendritic arbors in hippocampal neurons" (PDF). The Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (14): 5271–5285. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2387-10.2011. PMC 6622686. PMID 21471362. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-22.

- ^ Kandel ER (2003). Principles of neural science (4th ed.). Cambridge: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-7701-6.

- ^ Koch C (1999). Biophysics of computation : information processing in single neurons. New York [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-510491-9.

- ^ Häusser M (2008). Dendrites (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856656-4.

- ^ Desai-Chowdhry, Paheli; Brummer, Alexander B.; Savage, Van M. (2022-12-02). "How axon and dendrite branching are guided by time, energy, and spatial constraints". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 20810. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1220810D. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-24813-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9718790. PMID 36460669.

- ^ Gidon, Albert; Zolnik, Timothy Adam; Fidzinski, Pawel; Bolduan, Felix; Papoutsi, Athanasia; Poirazi, Panayiota; Holtkamp, Martin; Vida, Imre; Larkum, Matthew Evan (2020-01-03). "Dendritic action potentials and computation in human layer 2/3 cortical neurons". Science. 367 (6473): 83–87. Bibcode:2020Sci...367...83G. doi:10.1126/science.aax6239. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31896716.

- ^ Larkum, Matthew E.; Wu, Jiameng; Duverdin, Sarah A.; Gidon, Albert (2022). "The Guide to Dendritic Spikes of the Mammalian Cortex In Vitro and In Vivo". Neuroscience. 489: 15–33. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.02.009. PMID 35182699.

- ^ Ludwig, Mike; Apps, David; Menzies, John; Patel, Jyoti C.; Rice, Margaret E. (2016), "Dendritic Release of Neurotransmitters", Comprehensive Physiology, 7 (1), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: 235–252, doi:10.1002/cphy.c160007, ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4, PMC 5381730, PMID 28135005

- ^ Michmizos D, Koutsouraki E, Asprodini E, Baloyannis S. 2011. Synaptic Plasticity: A Unified Model to Address Some Persisting Questions. International Journal of Neuroscience, 121(6): 289-304. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/00207454.2011.556283

- ^ Hodassman S, Vardi R, Tugendhaft Y, Goldental A, Kanter I (April 2022). "Efficient dendritic learning as an alternative to synaptic plasticity hypothesis". Scientific Reports. 12 (1) 6571. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.6571H. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-10466-8. PMC 9051213. PMID 35484180.

- ^ Sardi S, Vardi R, Goldental A, Sheinin A, Uzan H, Kanter I (March 2018). "Adaptive nodes enrich nonlinear cooperative learning beyond traditional adaptation by links". Scientific Reports. 8 (1) 5100. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.5100S. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-23471-7. PMC 5865176. PMID 29572466.

- ^ Meir Y, Ben-Noam I, Tzach Y, Hodassman S, Kanter I (January 2023). "Learning on tree architectures outperforms a convolutional feedforward network". Scientific Reports. 13 (1) 962. Bibcode:2023NatSR..13..962M. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-27986-6. PMC 9886946. PMID 36717568.

- ^ Makarov, Roman; Pagkalos, Michalis; Poirazi, Panayiota (2023-12-01). "Dendrites and efficiency: Optimizing performance and resource utilization". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 83 102812. arXiv:2306.07101. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2023.102812. ISSN 0959-4388. PMC 10312813. PMID 37980803.

- ^ Kulkarni, Vaishali A.; Firestein, Bonnie L. (2012-05-01). "The dendritic tree and brain disorders". Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 50 (1): 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2012.03.005. ISSN 1044-7431. PMID 22465229.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 3_09 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center – "Slide 3 Spinal cord"

- Dendritic Tree – Cell Centered Database

- Stereo images of dendritic trees in Kryptopterus electroreceptor organs