Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Commissural fiber

View on Wikipedia

| Commissural fiber | |

|---|---|

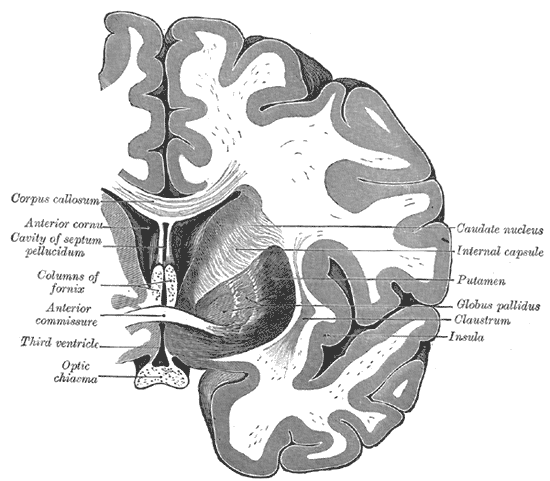

Coronal cross-section of brain showing the corpus callosum at top and the anterior commissure below | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | fibra commissuralis, fibrae commissurales telencephali |

| NeuroNames | 1220 |

| TA98 | A14.1.00.017 A14.1.09.569 |

| TA2 | 5603 |

| FMA | 75249 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The commissural fibers or transverse fibers are axons that connect the two hemispheres of the brain. Huge numbers of commissural fibers make up the commissural tracts in the brain, the largest of which is the corpus callosum.

In contrast to commissural fibers, association fibers form association tracts that connect regions within the same hemisphere of the brain, and projection fibers connect each region to other parts of the brain or to the spinal cord.[1]

Structure

[edit]The commissural fibers make up tracts that include the corpus callosum, the anterior commissure, and the posterior commissure, among other pathways.

Corpus callosum

[edit]The corpus callosum is the largest commissural tract in the human brain. It consists of about 200–300 million axons that connect the two cerebral hemispheres. The corpus callosum is essential to the communication between the two hemispheres.[2]

A recent study of individuals with agenesis of the corpus callosum suggests that the corpus callosum plays a vital role in problem solving strategies, verbal processing speed, and executive performance. Specifically, the absence of a fully developed corpus callosum is shown to have a significant relationship with impaired verbal processing speed and problem solving.[3]

Another study of individuals with multiple sclerosis provides evidence that structural and microstructural abnormalities of the corpus callosum are related to cognitive dysfunction. Particularly, verbal and visual memory, information processing speed, and executive tasks were shown to be impaired when compared to healthy individuals. Physical disabilities in multiple sclerosis patients also seem to be related to abnormalities of the corpus callosum, but not to the same extent of other cognitive functions.[4]

Using diffusion tensor imaging, researchers have been able to produce a visualization of this network of fibers, which shows the corpus callosum has an anteroposterior topographical organization that is uniform with the cerebral cortex.

Anterior commissure

[edit]The anterior commissure (also known as the precommissure) is a tract that connects the two temporal lobes of the cerebral hemispheres across the midline, and placed in front of the columns of the fornix. The great majority of fibers connecting the two hemispheres travel through the corpus callosum, which is over 10 times larger than the anterior commissure, and other routes of communication pass through the hippocampal commissure or, indirectly, via subcortical connections. Nevertheless, the anterior commissure is a significant pathway that can be clearly distinguished in the brains of all mammals.

Using diffusion tensor imaging, researchers were able to approximate the location of the anterior commissure where it crosses the midline of the brain. This tract can be observed to be in the shape of a bicycle as it branches through various areas of the brain. Through diffusion tensor imaging results, the anterior commissure was categorized into two fiber systems: 1) the olfactory fibers and 2) the non-olfactory fibers.[5]

Posterior commissure

[edit]The posterior commissure (also known as the epithalamic commissure) is a rounded nerve tract crossing the middle line on the dorsal aspect of the upper end of the cerebral aqueduct. It is important in the bilateral pupillary light reflex.

Evidence suggests the posterior commissure is a tract that plays a role in language processing between the right and left hemispheres of the brain. It connects the pretectal nuclei. A case study described recently in The Irish Medical Journal discussed the role the posterior commissure plays in the connection between the right occipital cortex and the language centers in the left hemisphere. This study explains how visual information from the left side of the visual field is received by the right visual cortex and then transferred to the word form system in the left hemisphere though the posterior commissure and the splenium. Disruption of the posterior commissure can cause alexia without agraphia. It is evident from this case study of alexia without agraphia that the posterior commissure plays a vital role in transferring information from the right occipital cortex to the language centers of the left hemisphere.[6]

Other

[edit]The lyra or hippocampal commissure, habenular commissure, interthalamic adhesion, commissure of superior colliculus, commissure of inferior colliculus, optic chiasm, supraoptic commissure,[7] and supramammilary commissure.[8]

Aging and function

[edit]Age-related decline in the commissural fiber tracts that make up the corpus callosum indicate the corpus callosum is involved in memory and executive function. Specifically, the posterior fibers of the corpus callosum are associated with episodic memory. Perceptual processing decline is also related to diminished integrity of occipital fibers of the corpus callosum. Evidence suggests that the genu of the corpus callosum does not contribute significantly to any one cognitive domain in the elderly. As fiber tract connectivity in the corpus callosum declines due to aging, compensatory mechanisms are found in other areas of the corpus callosum and frontal lobe. These compensatory mechanisms, increasing connectivity in other parts of the brain, may explain why elderly individuals still display executive function as a decline of connectivity is seen in regions of the corpus callosum.[9]

Older adults compared to younger adults show poorer performance in balance exercises and tests. A decline in white matter integrity of the corpus callosum in older individuals may explain declines in the ability to balance. Changes in the white matter integrity of the corpus callosum may also be related to cognitive and motor function decline as well. Decreased white matter integrity effects proper transmission and processing of sensorimotor information. White matter degeneration of the genu of the corpus callosum is also associated with gait, balance impairment, and the quality of postural control.[10]

Other animals

[edit]The corpus callosum allows for communication between the two hemispheres and is found only in placental mammals. The anterior commissure serves as the primary mode of interhemispheric communication in marsupials,[11][12] and which carries all the commissural fibers arising from the neocortex (also known as the neopallium), whereas in placental mammals the anterior commissure carries only some of these fibers).[13]

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 843 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 843 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Standring, Susan (2005). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (39th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 411. ISBN 9780443071683.

The nerve fibres which make up the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres are categorized on the basis of their course and connections. They are association fibres, which link different cortical areas in the same hemisphere; commissural fibres, which link corresponding cortical areas in the two hemispheres; or projection fibres, which connect the cerebral cortex with the corpus striatum, diencephalon, brain stem and the spinal cord.

- ^ Kollias, S. (2012). Insights into the Connectivity of the Human Brain Using DTI. Nepalese Journal of Radiology, 1(1), 78-91.

- ^ Hinkley LBN, Marco EJ, Findlay AM, Honma S, Jeremy RJ, et al. (2012) The Role of Corpus Callosum Development in Functional Connectivity and Cognitive Processing. PLoS ONE 7(8): e39804. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039804

- ^ Llufriu S, Blanco Y, Martinez-Heras E, Casanova-Molla J, Gabilondo I, et al. (2012) Influence of Corpus Callosum Damage on Cognition and Physical Disability in Multiple Sclerosis: A Multimodal Study. PLoS ONE 7(5): e37167. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037167

- ^ Kollias, S. (2012). Insights into the Connectivity of the Human Brain Using DTI. Nepalese Journal of Radiology, 1(1), 78-91.

- ^ Mulroy, E., Murphy, S., & Lynch, T. (2012). Alexia without Agraphia. Instructions for Authors, 105(7).

- ^ Hacking, Craig (February 24, 2019), "Supraoptic commissure", Radiopaedia.org, Radiopaedia.org, doi:10.53347/rID-66537, archived from the original on June 15, 2024, retrieved October 4, 2025

- ^ Lavrador, José Pedro; Ferreira, Vítor; Lourenço, Miguel; Alexandre, Inês; Rocha, Maria; Oliveira, Edson; Kailaya-Vasan, Ahilan; Neto, Lia (June 1, 2019). "White-matter commissures: a clinically focused anatomical review". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 41 (6): 613–624. doi:10.1007/s00276-019-02218-7. ISSN 1279-8517.

- ^ Voineskos, A. N., Rajji, T. K., Lobaugh, N. J., Miranda, D., Shenton, M. E., Kennedy, J. L., ... & Mulsant, B. H. (2012). Age-related decline in white matter tract integrity and cognitive performance: A DTI tractography and structural equation modeling study. Neurobiology of aging, 33(1), 21-34.

- ^ Bennett, I. J. (2012). Aging, implicit sequence learning, and white matter integrity.

- ^ Ashwell, Ken (2010). The Neurobiology of Australian Marsupials: Brain Evolution in the Other Mammalian Radiation, p. 50

- ^ Armati, Patricia J., Chris R. Dickman, and Ian D. Hume (2006). Marsupials, p. 175

- ^ Butler, Ann B., and William Hodos (2005). Comparative Vertebrate Neuroanatomy: Evolution and Adaptation, p. 361