Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heinkel He 111

View on Wikipedia

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and medium bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a wolf in sheep's clothing. Due to restrictions placed on Germany after the First World War prohibiting bombers, it was presented solely as a civil airliner, although from conception the design was intended to provide the nascent Luftwaffe with a heavy bomber.[4]

Key Information

Perhaps the best-recognised German bomber of World War II due to the distinctive, extensively glazed "greenhouse" nose of the later versions, the Heinkel He 111 was the most numerous Luftwaffe bomber during the early stages of the war. It fared well until it met serious fighter opposition during the Battle of Britain, when its defensive armament was found to be inadequate.[4] As the war progressed, the He 111 was used in a wide variety of roles on every front in the European theatre. It was used as a strategic bomber during the Battle of Britain, a torpedo bomber in the Atlantic and Arctic, and a medium bomber and a transport aircraft on the Western, Eastern, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and North African Front theatres.

The He 111 was constantly upgraded and modified, but had nonetheless become obsolete by the latter part of the war. The failure of the German Bomber B project forced the Luftwaffe to continue operating the He 111 in combat roles until the end of the war. Manufacture of the He 111 ceased in September 1944, at which point piston-engine bomber production was largely halted in favour of fighter aircraft. With the German bomber force virtually defunct, the He 111 was used for logistics.[4]

Production of the Heinkel continued after the war as the Spanish-built CASA 2.111. Spain received a batch of He 111H-16s in 1943 along with an agreement to licence-build Spanish versions. Its airframe was produced in Spain under licence by Construcciones Aeronáuticas SA. The design differed significantly only in the powerplant used, eventually being equipped with Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. These remained in service until 1973.

Development

[edit]Conception

[edit]

After its defeat in World War I, Germany was banned from operating an air force by the Treaty of Versailles. German re-armament began earnestly in the 1930s and was initially kept secret because the project violated the treaty. Early development work on bombers was disguised as a development program for civilian transport aircraft.[5]

Among the designers seeking to benefit from German re-armament was Ernst Heinkel. Heinkel decided to create the world's fastest passenger aircraft, a goal met with scepticism by Germany's aircraft industry and political leadership. Heinkel entrusted development to Siegfried and Walter Günter, both fairly new to the company and untested.[5]

In June 1933, Albert Kesselring visited Heinkel's offices.[5] Kesselring was head of the Luftwaffe Administration Office: at that point Germany did not have a State Aviation Ministry but only an aviation commissariat, the Luftfahrtkommissariat.[5] Kesselring was hoping to build a new air force out of the Flying Corps being constructed in the Reichswehr, and required modern aircraft.[5] Kesselring convinced Heinkel to move his factory from Warnemünde to Rostock – with its factory airfield in the coastal "Marienehe" region of Rostock (today "Rostock-Schmarl") and bring in mass production, with a force of 3,000 employees. Heinkel began work on the new design, which garnered urgency as the American Lockheed 12, Boeing 247 and Douglas DC-2 began to appear.[5]

Features of the He 111 were apparent in the Heinkel He 70. The first single-engined He 70 Blitz ("Lightning") rolled off the line in 1932 and immediately started breaking records.[6] In the normal four-passenger version, its speed reached 380 km/h (240 mph) when powered by a 447 kW (599 hp) BMW VI engine.[7] The He 70 had an elliptical wing, which the Günther brothers had already used in the Bäumer Sausewind before joining Heinkel. This wing design became a feature in this and many subsequent designs they developed. The He 70 drew the interest of the Luftwaffe, which was looking for an aircraft with both bomber and transport capabilities.[8]

The He 111 was a twin-engine version of the Blitz, preserving the elliptical inverted gull wing, small rounded control surfaces and BMW engines, so that the new design was often called the Doppel-Blitz ("Double Lightning"). When the Dornier Do 17 displaced the He 70, Heinkel needed a twin-engine design to match its competitors.[7] Heinkel spent 200,000-man hours designing the He 111.[9] The fuselage was lengthened to 17.4 m (57 ft) from 11.7 m (38 ft) and wingspan increased to 22.6 m (74 ft) from 14.6 m (48 ft).[7]

First flight

[edit]The first He 111 flew on 24 February 1935, piloted by chief test pilot Gerhard Nitschke, who was ordered not to land at the company's factory airfield at Rostock-Marienehe (today's Rostock-Schmarl neighbourhood), as this was considered too short, but at the central Erprobungstelle Rechlin test facility. He ignored these orders and landed back at Marienehe. He said that the He 111 performed slow manoeuvres well and that there was no danger of overshooting the runway.[10][11] Nitschke also praised its high speed "for the period" and "very good-natured flight and landing characteristics", stable during cruising, gradual descent and single-engined flight and having no nose-drop when the undercarriage was operated.[12] During the second test flight Nitschke revealed there was insufficient longitudinal stability during climb and flight at full power and the aileron controls required an unsatisfactory amount of force.[12]

By the end of 1935, prototypes V2 and V4 had been produced under civilian registrations D-ALIX, D-ALES and D-AHAO. D-ALES became the first prototype of the He 111A-1 on 10 January 1936 and received recognition as the "fastest passenger aircraft in the world", as its speed exceeded 402 km/h (250 mph).[13] The design would have achieved a greater total speed had the 750 kW (1,000 hp) DB 600 inverted-V12 engine that powered the Messerschmitt Bf 109s tenth through thirteenth prototypes been available.[8] Heinkel was forced initially to use the 480 kW (650 hp) BMW VI "upright" V12 liquid-cooled engine.[11]

During the war, British test pilot Eric Brown evaluated many Luftwaffe aircraft. Among them was an He 111H-1 of Kampfgeschwader 26 Löwengeschwader (Lions Wing) which was forced to land at the Firth of Forth on 9 February 1940. Brown described his impression of the He 111s unique greenhouse nose,

The overall impression of space within the cockpit area and the great degree of visual sighting afforded by the Plexiglas panelling were regarded as positive factors, with one important provision in relation to weather conditions. Should either bright sunshine or rainstorms be encountered, the pilot's visibility could be dangerously compromised either by glare throwback or lack of good sighting.[14]

Taxiing was easy and was only complicated by rain, when the pilot needed to slide back the window panel and look out to establish direction. On take off, Brown reported very little "swing" and the aircraft was well balanced. On landing, Brown noted that approach speed should be above 140 km/h (90 mph) and should be held until touchdown. This was to avoid a tendency by the He 111 to drop a wing, especially on the port side.[14]

Competition

[edit]In the mid-1930s, Dornier Flugzeugwerke and Junkers competed with Heinkel for Ministry of Aviation (German: Reichsluftfahrtministerium, abbreviated RLM) contracts. The main competitor to the Heinkel was the Junkers Ju 86. In 1935, comparison trials were undertaken with the He 111. At this point, the Heinkel was equipped with two BMW VI engines while Ju 86A was equipped with two Jumo 205Cs, both of which had 492 kW (660 hp). The He 111 had a slightly heavier takeoff weight of 8,220 kg (18,120 lb) compared to the Ju 86's 8,000 kg (18,000 lb) and the maximum speed of both aircraft was 311 km/h (193 mph).[12] The Ju 86 had a higher cruising speed of 285 km/h (177 mph), 14 km/h (9 mph) faster than the He 111. This stalemate was altered drastically by the appearance of the DB 600C, which increased the He 111's power by 164 kW (220 hp) per engine.[12] The Ministry of Aviation awarded both contracts. Junkers sped up development and production at a breathtaking pace, but their financial expenditure was huge. In 1934–1935, 3,800,000 RM (4½% of annual turnover) was spent. The Ju 86 appeared at many flight displays all over the world which helped sales to the Ministry of Aviation and abroad. Dornier, which was also competing with their Do 17, and Heinkel were not as successful. In production terms, the He 111 was more prominent with 8,000 examples produced[12] against just 846 Ju 86s,[9] and was therefore the Luftwaffe's most numerous type at the beginning of the Second World War.[12]

Design

[edit]

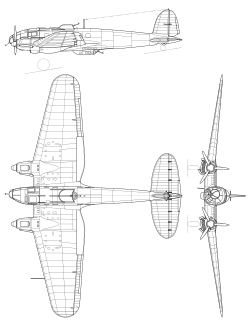

The design of the He 111 A-L initially had a conventional stepped cockpit, with a pair of windscreen-like panels for the pilot and co-pilot. The He 111P and subsequent production variants were fitted with fully glazed cockpits and a laterally asymmetric nose, with the port side having the greater curvature for the pilot, offsetting the bombardier to starboard. The resulting stepless cockpit, which was a feature on a number of German bomber designs during the war years in varying shapes and formats, no longer had the separate windscreen panels for the pilot. Pilots had to look outside through the same bullet-like glazing that was used by the bombardier and navigator. The pilot was seated on the left and the navigator/bomb aimer on the right. The navigator went forward to the prone bomb-aiming position or could tilt his chair to one side, to move into the rear of the aircraft. There was no cockpit floor below the pilot's feet—the rudder pedals being on arms—giving very good visibility below.[15] Sliding and removable panels were manufactured into the nose glazing to allow the pilot, navigator and or bomb aimer to exit the aircraft quickly, without a time-consuming retreat into the fuselage.[16]

The fuselage contained two major bulkheads, with the cockpit at the front of the first bulkhead. The nose was fitted with a rotating machine gun mount, offset to allow the pilot a better field of forward vision. The cockpit was fully glazed, with the exception of the lower right section, which acted as a platform for the bombardier-gunner. The commonly used Lotfernrohr-series bombsight penetrated through the cockpit floor into a protective housing on the outside of the cockpit.[15]

Between the forward and rear bulkhead was the bomb bay, which was constructed with a double-frame to strengthen it for carrying the bomb load. The space between the bomb bay and rear bulkhead was used up by Funkgerät radio equipment and contained the dorsal and flexible casemate ventral gunner positions. The rear bulkhead contained a hatch which allowed access into the rest of the fuselage which was held together by a series of stringers. The wing was a two spar design. The fuselage was formed of stringers to which the fuselage skin was riveted. Internally the frames were fixed only to the stringers, which made for simpler construction at the cost of some rigidity.[15]

The wing leading edges were swept back to a point inline with the engine nacelles, while the trailing edges were angled forward slightly. The wing contained two 700 L (150 imp gal; 180 US gal) fuel tanks between the inner wing main spars, while at the head of the main spar the oil coolers were fitted. Between the outer spars, a second pair of reserve fuel tanks were located, carrying an individual capacity of 910 L (200 imp gal; 240 US gal) of fuel.[15] The outer trailing edges were formed by the ailerons and flaps, which were met by smooth wing tips which curved forward into the leading edge. The outer leading edge sections were installed in the shape of a curved "strip nosed" rib, which was positioned ahead of the main spar. Most of the interior ribs were not solid, with the exception of the ribs located between the rear main spar and the flaps and ailerons. These were of solid construction, though even they had lightening holes.[15]

The control systems also had some innovations. The control column was centrally placed and the pilot sat on the port side of the cockpit. The column had an extension arm fitted and had the ability to be swung over to the starboard side in case the pilot was incapacitated. The control instruments were located above the pilot's head in the ceiling, which allowed viewing and did not block the pilot's vision.[17] The fuel instruments were electrical. The He 111 used the inner fuel tanks, closest to the wing root, first. The outer tanks acted as reserve tanks. The pilot was alerted to the fuel level when there was 100 L (22 imp gal; 26 US gal) left. A manual pump was available in case of electrical or power failure but the delivery rate of just 4.5 L (0.99 imp gal; 1.2 US gal) per minute demanded that the pilot fly at the lowest possible speed and just below 3,048 m (10,000 ft). The He 111 handled well at low speeds.[17]

The defensive machine gun positions were located in the glass nose and in the flexible ventral, dorsal and lateral positions in the fuselage, and all offered a significant field of fire.[18] The machine gun in the nose could be moved 10° upwards from the horizontal and 15° downwards.[18] It could traverse some 30° laterally. Both the dorsal and ventral machine guns could move up and downwards by 65°. The dorsal position could move the 13 mm (0.51 in) MG 131 machine gun 40° laterally, but the ventral Bola-mount 7.92 mm (0.312 in) twinned MG 81Z machine guns could be moved 45° laterally. Each MG 81 single machine gun mounted in the side of the fuselage in "waist" positions, could move laterally by 40° and could move upwards from the horizontal by 30° and downwards by 40°.[18]

Early civilian variants

[edit]He 111C

[edit]

The first prototype, He 111 V1 (W.Nr. 713, D-ADAP), flew from Rostock-Marienehe on 24 February 1935.[19] It was followed by the civilian-equipped V2 and V4 in May 1935. The V2 (W.Nr. 715, D-ALIX) used the bomb bay as a four-seat "smoking compartment", with another six seats behind it in the rear fuselage. V2 entered service with Deutsche Luft Hansa in 1936, along with six other newly built versions known as the He 111C.[20] The He 111 V4 was unveiled to the foreign press on 10 January 1936.[20] Nazi propaganda inflated the performance of the He 111C, announcing its maximum speed as 400 km/h (250 mph); in reality its performance stood at 360 km/h (220 mph).[21] The He 111 C-0 was a commercial version and took the form of the V4 prototype design. The first machine was designated D-AHAO "Dresden". It was powered by the BMW VI engine and could manage a range (depending on the fuel capacity) of 1,000 to 2,000 km (620 to 1,240 mi)[21] and a maximum speed of 310 km/h (190 mph).[22] The wing span on the C series was 22.6 m (74 ft).[22] The fuselage dimensions were 17.1 m (56 ft) in the He 111 V1, but changed in the C to 17.5 m (57 ft). The Jumo 205 diesel powerplant replaced the BMW VI. Nevertheless, the maximum speed remained in the 220 to 240 km/h (140 to 150 mph) bracket. This was increased slightly when the BMW 132 engines were introduced.[22]

A general problem existed in powerplants. The He 111 was equipped with BMW VI glycol-cooled engines. The German aviation industry lacked powerplants that could produce more than 600 hp.[11] Engines of suitable quality were kept for military use, frustrating German airline Luft Hansa and forcing it to rely on the BMW VI or 132s.[22]

He 111G

[edit]The He 111G was an upgraded variant and had a number of differences to its predecessors. To simplify production the leading edge of the wing was straightened, like the bomber version. Engine types used included the BMW 132, BMW VI, DB 600 and DB601A. Some C variants were upgraded with the new wing modifications. A new BMW 132H engine was also used in a so-called Einheitstriebwerk (unitary powerplant). These radial engines were used in the Junkers Ju 90 and the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor. The wing units and engines were packed together as complete operating systems, allowing for a quick change of engine[23] – a likely direct precursor of the wartime Kraftei aviation engine unitization concept. The He 111G was the most powerful as well as the fastest commercial version.[23] The G-0 was given the BMW VI 6.0 ZU. Later variants had their powerplants vary. The G-3 for example was equipped with the BMW 132. The G-4 was powered by DB600G inverted-vee 950 hp (710 kW) engines and the G-5 was given the DB601B with a top speed of 410 km/h (250 mph). By early 1937, eight G variants were in Lufthansa service. The maximum number of He 111s in Lufthansa service was 12. The He 111 operated all over Europe and flew as far away as South Africa. Commercial development ended with the He 111G.[23]

Military variants

[edit]He 111A – D

[edit]

The initial reports from the test pilot, Gerhard Nitschke, were favourable. The He 111's flight performance and handling were impressive although it dropped its wing in the stall. As a result, the passenger variants had their wings reduced from 25 to 23 m (82 to 75 ft). The military aircraft – V1, V3 and V5 had a span of 22.6 m (74 ft).[19]

The first prototypes were underpowered, as they were equipped with 431 kW (578 hp) BMW VI 6.0 V12 in-line engines. This was eventually increased to 745 kW (999 hp) with the installation of the DB (Daimler-Benz) 600 engines in the V5, which became the prototype of the "B" series.[19]

Only ten He 111 A-0 models based on the V3 were built, but they proved to be underpowered and were eventually sold to China. The type had been lengthened by 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in)) due to the extra 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 15 machine gun in the nose. Another gun position was installed on top of the fuselage, and a third in a ventral position as a retractable "dustbin" turret. The bomb bay was divided into two compartments and could carry 680 kg (1,500 lb) of bombs. The problem with these additions was that the weight of the aircraft reached 8,200 kg (18,100 lb). The He 111's performance was seriously reduced; in particular, the BMW VI 6.0 Z engines, which had been underpowered from the beginning, made the increase in weight even more problematic. The increased length also altered the 111's aerodynamic strengths and reduced its excellent handling on takeoffs and landings.[25]

The crews found the aircraft difficult to fly, and its top speed was reduced significantly. Production was shut down after the pilots reports reached the Ministry of Aviation. However, a Chinese delegation was visiting Germany and they considered the He 111 A-0 fit for their needs and purchased seven machines.[26]

The first He 111B made its maiden flight in the autumn of 1936. The first production batch rolled off the production lines that summer, at Rostock.[27] Seven B-0 pre-production aircraft were built, bearing the Werknummern (W.Nr./Works numbers) 1431 to 1437. The B-0s were powered by DB 600C engines fitted with variable pitch airscrews.[27] These increased output by 149 kW (200 hp). The B-0 had an MG 15 machine gun installed in the nose. The B-0 could also carry 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) in vertical cells.[27] The B-1 had some minor improvements, including the installation of a revolving gun mount in the nose and a flexible Ikaria turret under the fuselage.[27] After improvements, the RLM ordered 300 He 111 B-1s; the first were delivered in January 1937. In the B-2 variant, engines were upgraded to the supercharged 634 kW (850 hp) DB 600C, or in some cases, the 690 kW (930 hp) 600G. The B-2 began to roll off the production lines at Oranienburg in 1937.[28] The He 111 B-3 was a modified trainer. Some 255 B-1s were ordered.[27] However, the production orders were impossible to fulfill and only 28 B-1s were built.[27] Owing to the production of the new He 111E, only a handful of He 111 B-3s were produced. Due to insufficient capacity, Dornier, Arado and Junkers built the He 111B series at their plants in Wismar, Brandenburg and Dessau, respectively.[27] The B series compared favourably with the capacity of the A series. The bomb load increased to 1,500 kg (3,300 lb), while there was also an increase in maximum speed and altitude to 344 km/h (214 mph) and 6,700 m (22,000 ft).[13][26]

In late 1937, the D-1 series entered production. However, the DB 600Ga engine with 781 kW (1,047 hp) planned for this variant was instead allocated to Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Bf 110 production lines. Heinkel then opted to use Junkers Jumo engines, and the He 111 V6 was tested with Jumo 210 G engines, but was judged underpowered. However, the improved 745 kW (999 hp) Jumo 211 A-1 powerplant prompted the cancellation of the D series altogether and concentration on the design of the E series.[29]

He 111 E

[edit]

The pre-production E-0 series were built in small numbers, with Jumo 211 A-1 engines loaded with retractable radiators and exhaust systems. The variant could carry 1,700 kg (3,700 lb) of bombs, giving it a takeoff weight of 10,300 kg (22,700 lb). The development team for the Jumo 211 A-1 engines increased power to 690 kW (930 hp), subsequently the He 111 E-1s bomb load capacity increased to 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) and a top speed of 390 km/h (240 mph).[30]

The E-1 variant with Jumo 211A-1 engines was developed in 1937, the He 111 V6 being the first production variant. The E-1 had its original powerplant, the DB 600 replaced with the Jumo 210 Ga engines.[31] The more powerful Jumo 211 A-1 engines desired by the Ministry of Aviation were not ready; another trial aircraft, He 111 V10 (D-ALEQ) was to be fitted with two oil coolers necessary for the Jumo 211 A-1 installation.[31]

The E-1s came off the production line in February 1938, in time for a number of these aircraft to serve in the Condor Legion during the Spanish Civil War in March 1938.[32] The RLM thought that because the E variant could outrun enemy fighters in Spain, there was no need to increase the defensive weaponry, which would prove to be a mistake in later years.[31]

The fuselage bomb bay used four bomb racks but in later versions eight modular standard bomb racks were fitted, to carry one SC 250 kg (550 lb) bomb or four SC 50 kg (110 lb) bombs mounted nose up. These modular standard bomb racks were a common feature on the first generation of Luftwaffe bombers but they limited the ordnance selection to bombs of only two sizes and were abandoned in later designs.[31]

The E-2 series was not produced and was dropped in favour of producing the E-3 with only a few modifications, such as external bomb racks.[30] Its design features were distinguished by improved FuG radio systems.[32] The E-3 series was equipped with the Jumo 211 A-3s of 820 kW (1,100 hp).[32]

The E-4 variant was fitted with external bomb racks also and the empty bomb bay space was filled with an 835 L (184 imp gal; 221 US gal) tank for aviation fuel and a further 115 L (25 imp gal; 30 US gal) oil tank. This increased the loaded weight but increased range to 1,800 km (1,100 mi). The modifications allowed the He 111 to perform both long- and short-range missions.[33] The E-4's eight internal vertically aligned bomb racks could each carry a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb.[34] The last E Variant, the He 111 E-5, was powered by the Jumo 211 A-3 and retained the 835 L (184 imp gal; 221 US gal) fuel tank on the port side of the bomb bay. Only a few E-4 and E-5s were built.[32]

The RLM had acquired an interest in rocket boosters fitted, for the sake of simplicity, below the wings of a heavily loaded bomber, to cut down the length of runway needed for takeoff. Once in the air the booster canisters would be jettisoned by parachute for reuse. The firm of Hellmuth Walter, at Kiel, handled this development.[35] The first standing trials and tests flights of the Walter HWK 109-500 Starthilfe liquid-fueled boosters were held in 1937 at Neuhardenberg with test pilot Erich Warsitz at the controls of Heinkel He 111E bearing civil registration D-AMUE.[36]

He 111 F

[edit]The He 111 design quickly ran through a series of minor design revisions. One of the more obvious changes started with the He 111F models, which moved from the elliptical wing to one with straight leading and trailing edges, which could be manufactured more efficiently.[32] The new design had a wing span of 22.6 m (74 ft) and a wing area of 87.60 m2 (942.9 sq ft).[32]

Heinkel's industrial capacity was limited and production was delayed. Nevertheless, 24 machines of the F-1 series were exported to Turkey.[32] Another 20 of the F-2 variant were built.[37] The Turkish interest, prompted by the fact the tests of the next prototype, He 111 V8, was some way off, prompted the Ministry of Aviation to order 40 F-4s with Jumo 211 A-3 engines. These machines were built and entered service in early 1938.[29] This fleet was used as a transport group during the Demyansk Pocket and Battle of Stalingrad.[38] At this time, development began on the He 111J. It was powered by the DB 600 and was intended as a torpedo bomber. As a result, it lacked an internal bomb bay and carried two external torpedo racks. The Ministry of Aviation gave an order for the bomb bay to be retrofitted; this variant became known as the J-1. In all but the powerplant, it was identical to the F-4.[29]

The final variant of the F series was the F-5, with bombsight and powerplants identical to the E-5.[37] The F-5 was rejected as a production variant owing to the superior performance of the He 111 P-1.[37]

He 111 J

[edit]The He 111's low-level performance attracted the interest of the Kriegsmarine. The result was the He 111J, capable of carrying torpedoes and mines. However, the navy eventually dropped the program as they deemed the four-man crew too extravagant. The RLM continued production of the He 111 J-0. Some 90 (other sources claim 60) were built in 1938 and were then sent to Küstenfliegergruppe 806 (Coastal Flying Group).[39][40] Powered by the DB 600G engines, it could carry a 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) payload. Only a few of the pre-production J-0s were fitted with the powerplant, the DB 600 was used, performance deteriorated and the torpedo bomber was not pursued. The J variants were used in training schools until 1944.[37] Some J-1s were used as test beds for Blohm & Voss L 10 radio-guided air-to-ground torpedo missiles.[41]

He 111 P

[edit]

The He 111P incorporated the updated Daimler-Benz DB 601A-1 liquid-cooled engine and featured a newly designed nose section, including an asymmetric mounting for an MG 15 machine gun that replaced the 'stepped' cockpit with a roomier and more aerodynamic glazed stepless cockpit over the entire front of the aircraft. This smooth glazed nose was first tested on the He 111 V8 in January 1938. These improvements allowed the aircraft to reach 475 km/h (295 mph) at 5,000 m (16,000 ft) and a cruise speed of 370 km/h (230 mph), although a full bomb load reduced this figure to 300 km/h (190 mph).[29] The design was implemented in 1937 because pilot reports indicated problems with visibility.[29] The pilot's seat could actually be elevated, with the pilot's eyes above the level of the upper glazing, complete with a small pivoted windscreen panel, to get the pilot's head above the level of the top of the "glass tunnel" for a better forward view for takeoffs and landings. The rear-facing dorsal gun position, enclosed with a sliding, near-clear view canopy, and for the first time, the ventral Bodenlafette rear-facing gun position, immediately aft of the bomb bay, that replaced the draggy "dustbin" retractable emplacement became standard, having been first flown on the He 111 V23, bearing civil registration D-ACBH.[42]

One of Heinkel's rivals, Junkers, built 40 He 111Ps at Dessau. In October 1938, the Junkers Central Administration commented:

Apparent are the externally poor, less carefully designed components at various locations, especially at the junction between the empennage and the rear fuselage. All parts have an impression of being very weak.... The visible flexing in the wing must also be very high. The left and right powerplants are interchangeable. Each motor has an exhaust-gas heater on one side, but it is not connected to the fuselage since it is probable that ... the warm air in the fuselage is not free of carbon monoxide (CO). The fuselage is not subdivided into individual segments, but is attached over its entire length, after completion, to the wing centre section. Outboard of the powerplants, the wings are attached by universal joints. The latter can in no way be satisfactory and have been the cause of several failures.[43]

The new design was powered by the DB 601 Ba engine with 1,175 PS[29] The first production aircraft reached Luftwaffe units in Fall 1938. In May 1939, the P-1 and P-2 went into service with improved radio equipment. The P-1 variant was produced with two DB 601Aa powerplants of 1,150 hp (860 kW). It also introduced self-sealing fuel tanks.[44] The P-1 featured a semi-retractable tail wheel to decrease drag.[44] Armament consisted of an MG 15 in the nose, and a sliding hood for the fuselage's dorsal B-Stand position. Installation of upgraded FuG III radio communication devices were also made and a new ESAC-250/III vertical bomb magazine was added. The overall takeoff weight was now 13,300 kg (29,300 lb).[45]

The P-2, like the later P-4, was given stronger armour and two MG 15 machine guns in "waist" mounts on either side of the fuselage and two external bomb racks.[29] Radio communications consisted of FuG IIIaU radios and the DB601 A-1 replaced the 601Aa powerplants. The Lotfernrohr 7 bombsights, which became the standard bombsight for German bombers, were also fitted to the P-2. The P-2 was also given "field equipment sets" to upgrade the weak defensive armament to four or five MG 15 machine guns.[45] The P-2 had its bomb capacity raised to 4 ESA-250/IX vertical magazines.[45] The P-2 had an empty weight of 6,202 kg (13,673 lb), a loaded weight which had increased to 12,570 kg (27,710 lb) and a maximum range of 2,100 km (1,300 mi).[45]

The P-3 was powered with the same DB601A-1 engines. The aircraft was also designed to take off with a land catapult (KL-12). A towing hook was added to the fuselage under the cockpit for the cable. Just eight examples were produced, all without bomb equipment.[44]

The P-4 contained many changes from the P-2 and P-3. The jettisonable loads were capable of considerable variation. Two external SC 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) bombs, two LMA air-dropped anti-shipping mines, one SC 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) plus four SC 250 kg (550 lb); or one SC 2,500 kg (5,500 lb) external bomb could be carried on an ETC Rüstsatz rack. Depending on the load variation, an 835 L fuel and 120 L oil tank could be added in place of the internal bomb bay. The armament consisted of three defensive MG 15 machine guns.[44] later supplemented by a further three MG 15s and one MG 17 machine gun. The radio communications were standard FuG X(10), Peil G V direction finding and FuBI radio devices. Due to the increase in defensive firepower, the crew numbers increased from four to five. The empty weight of the P-4 increased to 6,775 kg (14,936 lb), and the full takeoff weight increased to 13,500 kg (29,800 lb).[44]

The P-5 was powered by the DB601A. The variant was mostly used as a trainer and at least twenty-four production variants were produced before production ceased.[37] The P-5 was also fitted with meteorological equipment, and was used in Luftwaffe weather units.[44]

Many of the He 111 Ps served during the Polish Campaign. With the Junkers Ju 88 experiencing technical difficulties, the He 111 and the Do 17 formed the backbone of the Kampfwaffe. On 1 September 1939, Luftwaffe records indicate the Heinkel strength at 705 (along with 533 Dorniers).[46]

The P-6 variant was the last production model of the He 111 P series. In 1940, the Ministry of Aviation abandoned further production of the P series in favour of the H versions, mostly because the P-series' Daimler-Benz engines were needed for Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighter production. The remaining P-6s were redesignated P-6/R2s and used as heavy glider tugs.[47] The most notable difference with previous variants was the upgraded DB 601N powerplants.[43]

The P-7 variant's history is unclear. The P-8 was said to have been similar to the H-5 fitted with dual controls.[43] The P-9 was produced as an export variant for the Hungarian Air Force. Due to the lack of DB 601E engines, the series was terminated in summer 1940.[43]

He 111H and its variants

[edit]He 111 H-1 to H-10

[edit]

The H variant of the He 111 series was more widely produced and saw more action during World War II than any other Heinkel variant. Owing to the uncertainty surrounding the delivery and availability of the DB 601 engines, Heinkel switched to 820 kW (1,100 hp) Junkers Jumo 211 powerplants, whose somewhat greater size and weight were regarded as unimportant considerations in a twin-engine design. When the Jumo was fitted to the P model it became the He 111 H. The He 111 H-1 was fitted with a standard set of three 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 15 machine guns and eight SC 250 250 kg (550 lb) or 32 SC 50 50 kg (110 lb) bombs. The same armament was used in the H-2 which started production in August 1939.[48] The P-series was gradually replaced on the eve of war with the new H-2, powered by improved Jumo 211 A-3 engines of 820 kW (1,100 hp).[48] A count on 2 September 1939 revealed that the Luftwaffe had a total of 787 He 111s in service, with 705 combat ready, including 400 H-1 and H-2s that had been produced in a mere four months.[49] Production of the H-3, powered by the 895 kW (1,200 hp) Jumo 211 D-1, began in October 1939. Experiences during the Polish Campaign led to an increase in defensive armament. MG 15s were fitted whenever possible and the number of machine guns was sometimes increased to seven. The two waist positions received an additional MG 15, and on some variants a belt-fed MG 17 was even installed in the tail.[48] A 20 mm (0.79 in) MG FF autocannon would sometimes be installed in the nose or forward gondola.[50]

After the Battle of Britain, smaller scale production of the H-4s began. The H-4 was virtually identical to the He 111 P-4 with the DB 600s swapped for the Jumo 211D-1s. Some also used the Jumo 211H-1.[51][52] This variant also differed from the H-3 in that it could either carry 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) of bombs internally or mount one or two external racks to carry one 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) or two 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) bombs. As these external racks blocked the internal bomb bay doors, a combination of internal and external storage was not possible. A PVR 1006L bomb rack was fitted externally and an 835 L (184 imp gal; 221 US gal) tank added to the interior spaces left vacant by the removal of the internal bomb-bay. The PVR 1006L was capable of carrying a SC 1000 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) bomb. Some H-4s had their PVC racks modified to drop torpedoes.[51] Later modifications enabled the PVC 1006 to carry a 2,500 kg (5,500 lb) "Max" bomb. However 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) "Hermann" or 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) "Satans" were used more widely.[53]

The H-5 series followed in February 1941, with heavier defensive armament.[54] Like the H-4, it retained a PVC 1006 L bomb rack to enable it to carry heavy bombs under the fuselage. The first ten He 111 H-5s were pathfinders, and selected for special missions. The aircraft sometimes carried 25 kg (55 lb) flashlight bombs which acted as flares. The H-5 could also carry heavy fire bombs, either heavy containers or smaller incendiary devices attached to parachutes. The H-5 also carried LM A and LM B aerial mines for anti-shipping operations. After the 80th production aircraft, the PVC 1006 L bomb rack was removed and replaced with a heavy-duty ETC 2000 rack, enabling the H-5 to carry the SC 2500 "Max" bomb, on the external ETC 2000 rack, which enabled it to support the 2,500 kg (5,500 lb) bomb.[55]

Some H-3 and H-4s were equipped with barrage balloon cable-cutting equipment in the shape of cutter installations forward of the engines and cockpit. They were designated H-8, but later named H8/R2. These aircraft were difficult to fly and production stopped. The H-6 initiated some overall improvements in design. The Jumo 211 F-1 engine of 1,007 kW (1,350 hp) increased its speed while the defensive armament was upgraded at the factory with one 20 mm (0.79 in) MG FF cannon in the nose and/or gondola positions (optional), two MG 15 in the ventral gondola, and one each of the fuselage side windows. Some H-6 variants carried tail-mounted MG 17 defensive armament.[56] The performance of the H-6 was much improved. The climb rate was higher and the bomber could reach a slightly higher ceiling of 8,500 m (27,900 ft). When heavy bomb loads were added, this ceiling was reduced to 6,500 m (21,300 ft). The weight of the H-6 increased to 14,000 kg (31,000 lb). Some H-6s received Jumo 211F-2s which improved a low-level speed of 365 km/h (227 mph). At an altitude of 6,000 m (20,000 ft) the maximum speed was 435 km/h (270 mph). If heavy external loads were added, the speed was reduced by 35 km/h (22 mph).[57]

Other designs of the mid-H series included the He 111 H-7 and H-8. The airframes were to be rebuilds of the H-3/H-5 variant. Both were designed as night bombers and were to have two Jumo 211F-1s installed. The intention was for the H-8 to be fitted with cable-cutting equipment and barrage ballon deflectors on the leading edge of the wings. The H-7 was never built.[58]

The H-9 was intended as a trainer with dual control columns. The airframe was a H-1 variant rebuild. The powerplants consisted of two JumoA-1s or D-1s.[58] The H-10 was also designated to trainer duties. Rebuilt from an H-2 or H-3 airframe, it was installed with full defensive armament including 13 mm (0.51 in) MG 131 and 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 81Z machine guns. It was to be powered by two Jumo 211A-1s, D-1s or F-2s.[58]

Later H variants, H-11 to H-20

[edit]In the summer of 1942, the H-11, based on the H-3 was introduced. With the H-11, the Luftwaffe had at its disposal a powerful medium bomber with heavier armour and revised defensive armament. The drum-fed 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 15 was replaced with a belt-fed 13 mm (0.51 in) MG 131 in a fully enclosed dorsal position (B-Stand); the gunner in the latter was protected with armoured glass. The MG 15 in the ventral C-Stand or Bola was also replaced, with a belt-fed 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 81Z with much higher rate of fire. The beam positions originally retained their MG 15s but the H-11/R1 replaced these with twin MG 81Z which was standardized in November 1942. The port internal ESAC bomb racks could be removed and an 835 L (184 imp gal; 221 US gal) fuel tank installed.[59] Many H-11s were equipped with a new PVC rack under the fuselage, which carried five 250 kg (550 lb) bombs. Additional armour plating was fitted around crew spaces, some of it on the lower fuselage which could be jettisoned in an emergency. Engines were two 1,000 kW (1,300 hp) Junkers Jumo 211F-2, allowing this variant to carry a 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) load to a range of 2,340 km (1,450 mi). Heinkel built 230 new aircraft of this type and converted 100 H-3s to H-11s by the summer of 1943.[59]

The third mass production model of the He 111H was the H-16, entering production in late 1942. Armament was as on the H-11, except that the 20 mm (0.79 in) MG FF cannon was removed, as the H-16s were seldom employed on low-level missions, and was replaced with an MG 131 in a flexible installation in the nose (A-Stand). On some aircraft, He 111 H-16/R1, the dorsal position was replaced by a Drehlafette DL 131 electrically powered turret, armed with an MG 131. The two beam and the aft ventral positions were provided with MG 81Zs, as on the H-11. The two 1,000 kW (1,300 hp) Jumo 211 F-2 provided a maximum speed of 434 km/h (270 mph) at 6,000 m (20,000 ft); cruising speed was 390 km/h (240 mph) and service ceiling was 8,500 m (27,900 ft).[60] Funkgerät (FuG) radio equipment. FuG 10P, FuG 16, FuBl Z and APZ 6 were fitted for communication and navigation at night, while some aircraft received the FuG 101a radio altimeter. The H-16 retained its eight ESAC internal bomb cells; four bomb cells, as on previous versions could be replaced by a fuel tank to increase range. ETC 2000 racks could be installed over the bomb cell openings for external weapons carriage. Empty weight was 6,900 kg (15,200 lb) and the aircraft weighed 14,000 kg (31,000 lb) fully loaded for take off. German factories built 1,155 H-16s between the end of 1942 and the end of 1943; in addition, 280 H-6s and 35 H-11s were updated to H-16 standard.[60] An undetermined number of H variants were fitted with the FuG 200 Hohentwiel. The radar was adapted as an anti-shipping detector for day or night operations.[61][62]

The last major production variant was the H-20, which entered into production in early 1944. It was planned to use two 1,305 kW (1,750 hp) Junkers Jumo 213E-1 engines, turning three-blade, Junkers VS 11 wooden-bladed variable-pitch propellers. It would appear this plan was never developed fully. Though the later H-22 variant was given the 213E-1 engines, the 211F-2 remained the H-20's main power plant. Heinkel and its licensees built 550 H-20s through the summer of 1944, while 586 H-6s were upgraded to H-20 standard.[63][64]

In contrast to the H-11 and H-16, the H-20, equipped with two Jumo 211F-2s, had more powerful armament and radio communications. The defensive armament consisted of an MG 131 in an A-Stand gun pod for the forward mounted machine gun position. One rotatable Drehlafette DL 131/1C (or E) gun mount in the B-stand was standard and later, MG 131 machine guns were added.[65] Navigational direction-finding gear was also installed. The Peil G6 was added to locate targets and the FuBI 2H blind landing equipment was built in to help with night operations. The radio was a standard FuG 10, TZG 10 and FuG 16Z for navigating to the target. The H-20 also was equipped with barrage balloon cable-cutters. The bomb load of the H-20 could be mounted on external ETC 1000 racks or four ESAC 250 racks. The sub variant H-20/R4 could carry twenty 50 kg (110 lb) bombs externally.[65]

He 111Z

[edit]

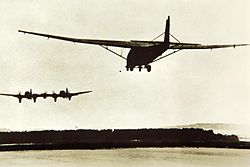

The He 111Z Zwilling (English: twin) was a design that mated two He 111s. The design was originally conceived to tow the Messerschmitt Me 321 glider. Initially, four He 111 H-6s were modified. This resulted in an aircraft with twin fuselages and five engines. They were tested at Rechlin in 1941, and the pilots rated them highly.[66]

A batch of ten were produced and five were built from existing H-6s. The machines were joined by a center wing formed by two sections 6.15 m (20.2 ft) in length. The powerplants were five Junkers Jumo 211F engines producing 1,000 kW (1,300 hp) each. The total fuel capacity was 8,570 L (1,890 imp gal; 2,260 US gal). This was increased by adding four 600 L (130 imp gal; 160 US gal) drop tanks.[39] The He111Z could tow a Gotha Go 242 or Messerschmitt Me 321 Gigant gliders for up to 10 hours at cruising speed. It could also remain airborne if the three central powerplants failed. The He 111 Z-2 and Z-3 were also planned as heavy bombers carrying 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) of bombs and having a range of 4,000 km (2,500 mi). The ETC installations allowed for a further four 600 L (130 imp gal; 160 US gal) drop tanks to be installed.

The He 111 Z-2 could carry four Henschel Hs 293 anti-ship missiles, which were guided by the FuG 203b Kehl III missile control system.[67] With this load, the He 111Z had a range of 1,094 km (680 mi) and a speed of 314 km/h (195 mph). The maximum bombload was 7,200 kg (15,900 lb). To increase power, the five Jumo 211F-2 engines were intended to be fitted with Hirth TK 11 superchargers. Onboard armament was the same as the He 111H-6, with the addition of one 20 mm (0.79 in) MG 151/20 cannon in a rotating gun-mount on the center section.

The layout of the He 111Z had the pilot and his controls in the port fuselage only. The controls themselves and essential equipment were all that remained in the starboard section. The aircraft had a crew of seven; a pilot, first mechanic, radio operator and gunner in the port fuselage, and the observer, second mechanic and gunner in the starboard fuselage.[39]

The Z-3 was to be a reconnaissance version and would have had additional fuel tanks, increasing its range to 6,000 km (3,700 mi). Production was due to take place in 1944, just as bomber production was being abandoned. The long-range variants failed to come to fruition.[68] The He 111Z was to have been used in an invasion of Malta in 1942 and as part of an airborne assault on the Soviet cities of Astrakhan and Baku in the Caucasus in the same year. During the Battle of Stalingrad their use was cancelled due to insufficient airfield capacity. Later in 1943, He111Zs helped evacuate German equipment and personnel from the Caucasus region, and during the Allied invasion of Sicily, attempted to deliver reinforcements to the island.[69]

During operations, the He 111Z did not have enough power to lift a fully loaded Me 321. Some He 111s were supplemented by rocket pods for extra takeoff thrust, but this was not a fleet-wide action. Two rockets were mounted beneath each fuselage and one underneath each wing. This added 500 kg (1,100 lb) in weight. The pods were released by parachute after takeoff.[39]

The He 111Z's operational history was minimal. One machine was caught by RAF fighter aircraft over France on 14 March 1944. The He 111Z was towing a Gotha Go 242, and was shot down.[70] Eight were shot down or destroyed on the ground in 1944.[71]

Production

[edit]

To meet demand for numbers, Heinkel constructed a factory at Oranienburg. On 4 May 1936, construction began, and exactly one year later the first He 111 rolled off the production line.[72] The Ministry of Aviation Luftwaffe administration office suggested that Ernst Heinkel lend his name to the factory. The "Ernst Heinkel GmbH" was established with a share capital of 5,000,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁. Heinkel was given a 150,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ share.[72] The factory itself was built by, and belonged to, the German state.[72] From this production plant, 452 He 111s and 69 Junkers Ju 88s were built in the first year of the war.[73] German production for the Luftwaffe amounted to 808 He 111s by September 1939.[74] According to Heinkel's memoirs, a further 452 were built in 1939, giving a total of 1,260.[74] "1940s production suffered extreme losses during the Battle of Britain, with 756 bombers lost".[73]

The He 111's rival – the Ju 88 – had increased production to 1,816 aircraft, some 26 times the number from the previous year.[73] Losses were also considerable the previous year over the Balkans and Eastern Fronts. To compensate, He 111 production was increased to 950 in 1941.[74] In 1942, this increased further to 1,337 He 111s.[73][74] The Ju 88 production figures were even higher still, exceeding 3,000 in 1942, of which 2,270 were bomber variants.[73] In 1943, He 111 increased to 1,405 aircraft.[73][74] The Ju 88 still outnumbered it in production as its figures reached 2,160 for 1943.[73] The Allied bomber offensives in 1944 and in particular Big Week failed to stop or damage production at Heinkel. Up until the last quarter of 1944, 756 Heinkel He 111s had been built, while Junkers produced 3,013 Ju 88s, of which 600 were bomber versions.[73][74] During 1939–1944, a total of 5,656 Heinkel He 111s were built compared to 9,122 Ju 88s.[73] As the Luftwaffe was on the strategic defensive, bomber production and that of the He 111 was suspended. Production in September 1944, the last production month for the He 111, included 118 bombers.[75] Of these 21 Junkers Ju 87s, 74 Junkers Ju 188s, 3 Junkers Ju 388s and 18 Arado Ar 234s were built.[75] Of the Heinkel variants, zero Heinkel He 177s were produced and just two Heinkel He 111s were built.[75]

| Year | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quarter | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| Number Produced | 301 | 350 | 356 | 330 | 462 | 340 | 302 | 301 | 313 | 317 | 126 | 0 |

Exports

[edit]In 1937, 24 He 111 F-1s were bought by the Turkish Air Force. The Turks also ordered four He 111 G-5s.[75] China also ordered 12 He 111 A-0s, but at a cost 400,000 Reichsmark (RM).[75] The aircraft were crated up and transported by sea. According to other sources, China got only six He 111 K (export version of He 111 A), delivered in 1936.[76] At the end of the Spanish Civil War, the Spanish Air Force acquired 59 He 111 "survivors" and a further six He 111s in 1941–1943.[75] Bulgaria was given one He 111 H-6, Romania received 10 E-3s, 32 H-3s and 10 H-6s.[75] Two H-10s and three H-16s were given to Slovakia, Hungary was given three He 111Bs and 12–13 He 111s by 6 May 1941.[75] A further 80 P-1s were ordered but only 13 arrived.[75] Towards the end of 1944, 12 He 111 Hs were delivered. The Japanese were due to receive 44 He 111Fs but in 1938 the agreement was cancelled.[75]

Operational history

[edit]The Heinkel He 111 served the Luftwaffe across the European theatre as a medium bomber until 1943, when a loss of air superiority resulted in it being relegated to a transport role.

The Spanish supplemented the German-built He 111s still in service with licence-built CASA 2.111s from 1950. The last of the German-built aircraft were still in service in 1958.[77]

Variants

[edit]- He 111 A-0

- Ten aircraft built based on He 111 V3, two used for trials at Rechlin, rejected by Luftwaffe, all 10 were sold to China.[27]

- He 111 B-0

- Pre-production aircraft, similar to He 111 A-0, but with DB600Aa engines.

- He 111 B-1

- Production aircraft as B-0, but with DB600C engines. Defensive armament consisted of a flexible Ikaria turret in the nose A Stand, a B Stand with one DL 15 revolving gun-mount and a C Stand with one MG 15.[27]

- He 111 B-2

- As B-1, but with DB600GG engines, and extra radiators on either side of the engine nacelles under the wings. Later the DB 600Ga engines were added and the wing surface coolers withdrawn.[27]

- He 111 B-3

- Modified B-1 for training purposes.[27]

- He 111 C-0

- Six pre-production aircraft.

- He 111 D-0

- Pre-production aircraft with DB600Ga engines.[27]

- He 111 D-1

- Production aircraft, only a few built. Notable for the installation of the FuG X, or FuG 10, designed to operate over longer ranges. Auxiliary equipment contained direction finding Peil G V and FuBI radio blind landing aids.[32]

- He 111 E-0

- Pre-production aircraft, similar to B-0, but with Jumo 211 A-1 engines.

- He 111 E-1

- Production aircraft with Jumo 211 A-1 powerplants. Prototypes were powered by Jumo 210G as which replaced the original DB 600s.[32]

- He 111 E-2

- Non production variant. No known variants built. Designed with Jumo 211 A-1s and A-3s.[32]

- He 111 E-3

- Production bomber. Same design as E-2, but upgraded to standard Jumo 211 A-3s.[32]

- He 111 E-4

- Half of 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) bomb load carried externally.[32]

- He 111 E-5

- Fitted with several internal auxiliary fuel tanks.[32]

- He 111 F-0

- Pre-production aircraft similar to E-5, but with a new wing of simpler construction with a straight rather than curved taper, and Jumo 211 A-1 engines.[37]

- He 111 F-1

- Production bomber, 24 were exported to Turkey.[37]

- He 111 F-2

- Twenty were built. The F-2 was based on the F-1, differing only in installation of optimised wireless equipment.[37]

- He 111 F-3

- Planned reconnaissance version. Bomb release equipment replaced with RB cameras. It was to have Jumo 211 A-3 powerplants.[37]

- He 111 F-4

- A small number of staff communications aircraft were built under this designation. Equipment was similar to the G-5.[37]

- He 111 F-5

- The F-5 was not put into production. The already available on the P variant showed it to be superior.[37]

- He 111 G-0

- Pre-production transportation aircraft built, featured new wing introduced on F-0.

- He 111 G-3

- Also known as V14, fitted with BMW 132Dc radial engines.

- He 111 G-4

- Also known as V16, fitted with DB600G engines.

- He 111 G-5

- Four aircraft with DB600Ga engines built for export to Turkey.

- He 111 J-0

- Pre-production torpedo bomber similar to F-4, but with DB600CG engines.[37]

- He 111 J-1

- Production torpedo bomber, 90 built, but re-configured as a bomber.

- He 111 K

- Export version of He 111 A for China.[76]

- He 111 L

- Alternative designation for the He 111 G-3 civil transport aircraft.

- He 111 P-0

- Pre-production aircraft featured new straight wing, new glazed nose, DB601Aa engines, and a ventral Bodenlafette gondola for gunner (rather than "dust-bin" on previous models).[45]

- He 111 P-1

- Production aircraft, fitted with three MG 15s as defensive armament.

- He 111 P-2

- Had FuG 10 radio in place of FuG IIIaU. Defensive armament increased to five MG 15s.[45]

- He 111 P-3

- Dual control trainer fitted with DB601 A-1 powerplants.[45]

- He 111 P-4

- Fitted with extra armour, three extra MG 15s, and provisions for two externally mounted bomber racks. Powerplants consisted of DB601 A-1s. The internal bomb bay was replaced with an 835 L fuel tank and a 120 L oil tank.[45] Some H-4s were also fitted with Jumo 211H-1s.[52]

- He 111 P-5

- The P-5 was a pilot trainer. Some 24 examples were built. The variant was powered by DB 601A engines.[45]

- He 111 P-6

- Some of the P-6s were powered by the DB 601N engines. The Messerschmitt Bf 109 received these engines, as they had greater priority.[45]

- He 111 P-6/R2

- Equipped with /Rüstsatz 2 field conversions later in war of surviving aircraft to glider tugs.

- He 111 P-7

- Never built.[43]

- He 111 P-8

- Its existence and production is in doubt.[43]

- He 111 P-9

- It was intended for export to the Hungarian Air Force, by the project founder for lack of DB 601E engines. Only a small number were built, and were used in the Luftwaffe as towcraft.[43]

- He 111 H-0

- Pre-production aircraft similar to P-2 but with Jumo 211A-1 engines, pioneering the use of the Junkers Jumo 211 series of engines for the H-series as standard.

- He 111 H-1

- Production aircraft. Fitted with FuG IIIaU and later FuG 10 radio communications.

- He 111 H-2

- This version was fitted with improved armament. Two D Stands (waist guns) in the fuselage giving the variant some five MG 15 Machine guns.

- He 111 H-3

- Similar to H-2, but with Jumo 211 A-3 engines. The number of machine guns could be increased to seven with some variants having a belt-fed MG 17 installed in the tail. An MG FF cannon would sometimes be installed in the nose or front gondola[48][78]

- He 111 H-4

- Fitted with Jumo 211D engines, late in production changed to Jumo 211F engines, and two external bomb racks. Two PVC 1006L racks for carrying torpedoes could be added.[79]

- He 111 H-5

- Similar to H-4, all bombs carried externally, internal bomb bay replaced by fuel tank. The variant was to be a longer range torpedo bomber.[79]

- He 111 H-6

- Torpedo bomber, could carry two LT F5b torpedoes externally, powered by Jumo 211F-1 engines, had six MG 15s with optional MG FF cannon in nose and/or forward gondola.[79]

- He 111 H-6

- Modified H-6 with Heinkel HeS-11 jet engine attached below.[80]

- He 111 H-7

- Designed as a night bomber. Similar to H-6, tail MG 17 removed, ventral gondola removed, and armoured plate added. Fitted with Kuto-Nase barrage balloon cable-cutters.[79]

- He 111 H-8

- The H-8 was a rebuild of H-3 or H-5 aircraft, but with balloon cable-cutting fender. The H-8 was powered by Jumo 211D-1s.[79]

- He 111 H-8/R2

- Equipped with /Rüstsatz 2 field conversion of H-8 into glider tugs, balloon cable-cutting equipment removed.

- He 111 H-9

- Based on H-6, but with Kuto-Nase balloon cable-cutters.

- He 111 H-10

- Similar to H-6, but with 20 mm (0.79 in) MG/FF cannon in ventral gondola, and fitted with Kuto-Nase balloon cable-cutters. Powered by Jumo 211 A-1s or D-1s.[79]

- He 111 H-11

- Had a fully enclosed dorsal gun position and increased defensive armament and armour. The H-11 was fitted with Jumo 211 F-2s.[79]

- He 111 H-11/R1

- As H-11, but equipped with /Rüstsatz 1 field conversion kit, with two 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 81Z twin-gun units at waist positions.

- He 111 H-11/R2

- As H-11, but equipped with /Rüstsatz 2 field conversion kit, for conversion to a glider tug.

- He 111 H-12

- Modified to carry Hs 293A missiles, fitted with FuG 203b Kehl transmitter, and ventral gondola deleted.[79]

- He 111 H-14

- Pathfinder, fitted with FuG FuMB 4 Samos and FuG 16 radio equipment.[79]

- He 111 H-14/R1

- Glider tug version.

- He 111 H-15

- The H-15 was intended as a launch pad for the Blohm & Voss BV 246.[79]

- He 111 H-16

- Fitted with Jumo 211 F-2 engines and increased defensive armament of MG 131 machine guns, twin MG 81Zs, and an MG FF cannon.

- He 111 H-16/R1

- As H-16, but with MG 131 in power-operated dorsal turret.

- He 111 H-16/R2

- As H-16, but converted to a glider tug.

- He 111 H-16/R3

- As H-16, modified as a pathfinder.

- He 111 H-18

- Based on H-16/R3, was a pathfinder for night operations.

- He 111 H-20

- Defensive armament similar to H-16, but some aircraft feature power-operated dorsal turrets.

- He 111 H-20/R1

- Could carry sixteen paratroopers, fitted with jump hatch.

- He 111 H-20/R2

- Was a cargo carrier and glider tug.

- He 111 H-20/R3

- Was a night bomber.

- He 111 H-20/R4

- Could carry twenty 50 kg (110 lb) SC 50 bombs.

- He 111 H-21

- Based on the H-20/R3, but with Jumo 213 engines.

- He 111 H-22

- Re-designated and modified H-6, H-16, and H-21's used to air launch V1 flying-bombs.

- He 111 H-23

- Based on H-20/Rüstsatz 1 (/R1) field conversion kit, but with Jumo 213 A-1 engines.

- He 111 R

- High altitude bomber project.

- He 111 U

- A spurious designation applied for propaganda purposes to the Heinkel He 119 high-speed reconnaissance bomber design which set an FAI record in November 1937. True identity only becomes clear to the Allies after World War II.[81]

- He 111 Z-1

- Two He 111 airframes coupled together by a new central wing panel possessing a fifth Jumo 211 engine, used as a glider tug for Messerschmitt Me 321.

- He 111 Z-2

- Long-range bomber variant based on Z-1.

- He 111 Z-3

- Long-range reconnaissance variant based on Z-1.

- CASA 2.111

- The Spanish company CASA also produced a number of heavily modified He 111s under licence for indigenous use. These models were designated CASA 2.111 and served until 1973.

- Army Type 98 Medium Bomber

- Evaluation and proposed production of the He 111 for the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service

Operators

[edit]

Military operators

[edit]- Czechoslovak Air Force operated one aircraft post-war.[83]

- Soviet Air Forces operated several captured He 111s during World War II.[84]

- Turkish Air Force operated 24 He 111F-1s, with first deliveries in 1937, and remaining in use until 1944.[87][88]

- Royal Air Force operated various captured variants during and after the war for evaluation purposes i.e. to discover strengths and weaknesses.[89]

- United States Army Air Forces operated several captured aircraft after the war. One H-20 – 23 may be the aircraft currently on display at the RAF Museum Hendon, minus the Drehlafette DL 131 turret.[90]

Civil operators

[edit]- Central Air Transport Corporation (CATC) operated a single ex-air force He 111A re-fitted with Wright Cyclone radial engines.[91]

- Deutsche Luft Hansa operated 12 aircraft.[71]

- Unknown civilian user operated one converted bomber. The registration of the He 111 was YR-PTP. Works, or factory number is unknown.[92]

Surviving aircraft

[edit]

Five original German-built He 111s are on display or in museums around the world (not including major components):[93]

- He 111 E-1 "Pedro" (code 25+82), Wk Nr 2940 with the "conventional" cockpit is on display at the Museo del Aire, Madrid, Spain.[94][93]

- A mostly complete He 111 P-2 (5J+CN), Werknummer 1526 of 5.Staffel/Kampfgeschwader 54 (KG 54—Bomber Wing 54), is on display at the Royal Norwegian Air Force Museum at Gardermoen, part of the Norwegian Armed Forces Aircraft Collection.[93] The 5J Geschwaderkennung code on the aircraft is usually documented as being that of either I. Gruppe/KG 4 or KG 100 with B3 being KG 54's equivalent code throughout the war.[95]

- An He 111 H-20 (Stammkennzeichen of NT+SL), Wk Nr 701152, a troop-carrying version is on display at the Royal Air Force Museum London, Hendon, London. Appropriated by USAAF pilots in France at the end of the war, it was left in Britain following the unit's return to the US, and taken on by the RAF.[96][97]

- In September 2004, an He 111 H-2 (Stammkennzeichen of 6N+NH), and Wk Nr 2320 was salvaged from Jonsvatnet, a Norwegian lake, and has since been moved to Germany for restoration. The aircraft was formerly assigned to 1. Staffel/Kampfgeschwader 100, and was abandoned when the lake's surface ice began to melt, sometime in late 1940.[93]

- In 2019, a CASA 2.111B slated for restoration by the Kent Battle of Britain Museum is believed to be a refitted He 111 H-16.[98][failed verification]

Specifications (He 111 H-16)

[edit]

Data from Heinkel He 111: A Documentary History [99]

General characteristics

- Crew: 5 (pilot, navigator/bombardier/nose gunner, ventral gunner, dorsal gunner/radio operator, side gunner)[100]

- Length: 16.4 m (53 ft 10 in)

- Wingspan: 22.6 m (74 ft 2 in)

- Height: 4 m (13 ft 1 in)

- Wing area: 87.6 m2 (943 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 8,680 kg (19,136 lb)

- Gross weight: 12,030 kg (26,522 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 14,000 kg (30,865 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Junkers Jumo 211F-1 or Junkers Jumo 211F-2 V-12 inverted liquid-cooled piston engines, 970 kW (1,300 hp) each (Jumo 211F-1)

- 1,000 kW (1,340 hp) (Jumo 211F-2)

- Propellers: 3-bladed variable-pitch propellers

Performance

- Maximum speed: 440 km/h (270 mph, 240 kn)

- Range: 2,300 km (1,400 mi, 1,200 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 6,500 m (21,300 ft)

- Time to altitude: 5,185 m (17,000 ft) in 20 minutes

- Wing loading: 137 kg/m2 (28 lb/sq ft)

- Power/mass: 0.161 kW/kg (0.098 hp/lb)

Armament

- Guns: ** up to 7 × 7.92 mm (0.312 in) MG 15 machine guns or 7x MG 81 machine gun (2 in the nose, 1 in the dorsal, 2 in the side, 2 in the ventral), some of them replaced or augmented by

- 1 × 20 mm (0.787 in) MG FF cannon (central nose mount or forward ventral position)

- 1 × 13 mm (0.512 in) MG 131 machine gun (mounted dorsal and/or ventral rear positions)

- Bombs: ** 2,000 kilograms (4,400 lb) in the main internal bomb bay

- Up to 3,600 kilograms (7,900 lb) could be carried externally. External bomb racks blocked the internal bomb bay. Carrying bombs externally increased weight and drag and impaired the aircraft's performance significantly. Carrying the maximum load usually required rocket-assisted take-off.[44]

In popular culture

[edit]See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Bloch MB.210

- Caproni Ca.135

- Ilyushin Il-4

- Junkers Ju 86

- Junkers Ju 88

- Martin B-26 Marauder

- Mitsubishi G4M

- North American B-25 Mitchell

- PZL.37 Łoś

- Vickers Wellington

Related lists

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Nowarra 1980, p. 233

- ^ Munson 1978, p. 72.

- ^ Cruz 1998, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Mackay 2003, p. 7

- ^ a b c d e f Nowarra 1980, p. 26

- ^ Donald 1999, p. 494.

- ^ a b c Mackay 2003, p. 8

- ^ a b Mackay 2003, p. 9

- ^ a b Regnat 2004, p. 26

- ^ Mackay 2003, pp. 9–10

- ^ a b c Nowarra 1980, p. 28

- ^ a b c d e f Regnat 2004, p. 10

- ^ a b Mackay 2003, p. 10

- ^ a b Mackay 2003, p. 105

- ^ a b c d e Mackay 2003, p. 14

- ^ Nowarra 1980, p. 165

- ^ a b Mackay 2003, p. 18

- ^ a b c Regnat 2004, p. 58

- ^ a b c Dressel & Griehl 1994, p. 32.

- ^ a b Nowarra 1980, p. 30

- ^ a b Regnat 2004, p. 14

- ^ a b c d Regnat 2004, p. 17

- ^ a b c Regnat 2004, p. 21

- ^ Andersson 2008, p. 270

- ^ Janowicz 2004, p. 15

- ^ a b c Janowicz 2004, p. 16

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Regnat 2004, p. 28

- ^ Dressel & Griehl 1994, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dressel & Griehl 1994, p. 34.

- ^ a b Nowarra 1980, p. 66

- ^ a b c d Griehl 2006, p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Regnat 2004, p. 31

- ^ Janowicz 2004, p. 23

- ^ Mackay 2003, p. 12

- ^ Warsitz 2009, p. 41

- ^ Warsitz 2009, p. 45

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Regnat 2004, p. 32

- ^ Janowicz 2004, p. 25

- ^ a b c d Regnat 2004, p. 71

- ^ Janowicz 2004, p. 27

- ^ Nowarra 1980, p. 87

- ^ Wagner & Nowarra 1971, p. 290.

- ^ a b c d e f g Regnat 2004, p. 37

- ^ a b c d e f g Regnat 2004, p. 35

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Regnat 2004, p. 34

- ^ Nowarra 1990, p. 37

- ^ Dressel & Griehl 1994, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Janowicz 2004, p. 42

- ^ Dressel & Griehl 1994, p. 36.

- ^ Punka 2002, p. 24.

- ^ a b Janowicz 2004, p. 48

- ^ a b Nowarra 1980, p. 139

- ^ Mackay 2003, p. 94

- ^ Griehl 2006, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Griehl 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Dressel & Griehl 1994, p. 37.

- ^ Griehl 2008, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Regnat 2004, p. 81

- ^ a b Punka 2002, p. 35

- ^ a b Punka 2002, p. 46

- ^ Nowarra 1980, pp. 214

- ^ Goss 2007, p. 144.

- ^ Punka 2002, pp. 47–48

- ^ Regnat 2004, p. 63.

- ^ a b Regnat 2004, p. 62

- ^ Janowicz 2004, p. 69

- ^ Regnat 2004, p. 73

- ^ Janowicz 2004, pp. 70–71

- ^ Mackay 2003, p. 167

- ^ Nowarra 1980, p. 222

- ^ a b Nowarra 1980, p. 229

- ^ a b c Nowarra 1980, p. 63

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Regnat 2004, p. 74

- ^ a b c d e f Nowarra 1980, p. 231

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Regnat 2004, p. 77

- ^ a b Andersson 2008, p. 270.

- ^ Cruz 1998, pp. 32, 35.

- ^ Punka 2002, pp. 23, 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Regnat 2004, p. 61

- ^ Die deutsche Luftrüstung 1933-1945, Bd.4: Flugzeugtypen MIAG - Zeppelin

- ^ Donald 1998, p. 33

- ^ Mackay 2003, pp. 187, 189

- ^ Nowarra 1980, pp. 244–245

- ^ a b c Mackay 2003, p. 186

- ^ Mackay 2003, p. 187

- ^ Nowarra 1980, pp. 246

- ^ Griehl 2006, p. 34.

- ^ Air International September 1987, p. 133

- ^ Mackay 2003, p. 119

- ^ Mackay 2003, p. 177

- ^ Andersson 2008, pp. 217–218, 270

- ^ Nowarra 1980, p. 245

- ^ a b c d "List of He 111 survivors." preservedaxisaircraft.com. Retrieved: 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Hangar 1 del Museo de Aeronáutica y Astronáutica". Ejército del Aire (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Heinkel He 111P-2". Flysamlingen Forsvarets Museer (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Simpson, Andy. "Individual Record: Heinkel He 111 H-20/R1 701152/8471M, accession record 78/A/1033" (pdf). Archived 23 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine RAF Museum, 2007. Retrieved: 10 February 2011.

- ^ Hendrix, Kris (19 March 2020). "How an American saved our German Heinkel He 111". Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Heinkel Project". Kent Battle of Britain Museum. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Nowarra 1980, p. 251

- ^ Regnat 2004, p. 36

Bibliography

[edit]- Andersson, Lennart (2008). A History of Chinese Aviation: Encyclopedia of Aircraft and Aviation in China to 1949. Taipei, Republic of China: AHS of ROC. ISBN 978-9572853337.

- Andersson, Lennart (March–April 1999). "Round-Out". Air Enthusiast. No. 80. p. 80. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Cruz, Gonzalo Avila (September 1998). "Pequenos and Grandes: Earlier Heinkel He 111s in Spanish Service". Air Enthusiast. Vol. 77. pp. 29–35. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Donald, David (1998). An Industry of Prototypes: Heinkel He 119. Wings of Fame. Vol. 12. London/Westport, Connecticut: Aerospace Publishing. pp. 30–35. ISBN 1861840217.

- Donald, David, ed. (1999). The Encyclopedia of Civil Aircraft. London, UK: Aurum Publishing. ISBN 1-85410-642-2.

- Dressel, Joachim; Griehl, Manfred (1994). Bombers of the Luftwaffe. London, UK: DAG Publications. ISBN 1854091409.

- Goss, Chris (2007). Sea Eagles Volume Two: Luftwaffe Anti-Shipping Units 1942–45. Burgess Hill, UK: Classic Publications. ISBN 978-1903223567.

- Griehl, Manfred (2006). Heinkel He 111: The Early variants A–G and J of the Standard Bomber Aircraft of the Luftwaffe in World War II. World War II Combat Aircraft Photo Archive ADC 004. Part 1. Ravensburg, Germany: Air Doc, Laub. ISBN 3935687435.

- Griehl, Manfred (2008) [1994]. Heinkel He 111: P and Early H variants of the Standard Bomber Aircraft of the Luftwaffe in World War II: Part 2. World War II Combat Aircraft Photo Archive. Ravensburg, Germany: Air Doc, Laub. ISBN 978-3935687461. ADC 007.

- Janowicz, Krzysztof (2004). Heinkel He 111: Volume 1. Lublin, Poland: Kagero. ISBN 978-8389088260.

- Lawrence, Joseph (1945). The Observer's Book Of Airplanes. London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co.

- Mackay, Ron (2003). Heinkel He 111. Crowood Aviation Series. Ramsbury, Wiltshire, UK: Crowood. ISBN 186126576X.

- Munson, Kenneth (1978). German Aircraft Of World War 2 in colour. Poole, Dorsett, UK: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-0860-3.

- Nowarra, Heinz J. (1990). The Flying Pencil. Atglen, PA: Schiffer. ISBN 0887402364.

- Nowarra, Heinz J. (1980). Heinkel He 111: A Documentary History. London, UK: Janes. ISBN 0710600461.

- Punka, György (2002). Heinkel He 111 in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal. ISBN 0897474465.

- Regnat, Karl-Heinz (2004). Black Cross Volume 4: Heinkel He 111. Hersham, UK: Midland. ISBN 978-1857801842.

- "The Classic Heinkel: Part Two - From First to Second Generation". Air International. September 1987. pp. 128–136. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Warsitz, Lutz (2009). The First Jet Pilot: The Story of German Test Pilot Erich Warsitz. London, UK: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1844158188. (Including early developments and test flights of the Heinkel He 111 fitted with rocket boosters)

- Wagner, Ray; Nowarra, Heinz (1971). German Combat Planes: A Comprehensive Survey and History of the Development of German Military Aircraft from 1914 to 1945. New York City: Doubleday. p. 112. OCLC 491279937.

Further reading

[edit]- Arraez Cerda, Juan (September 1996). "Les Heinkel He 111 espagnols (1ère partie)" [Spanish Heinkel He 111s]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French). No. 42. pp. 36–39. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Arraez Cerda, Juan (October 1996). "Les Heinkel He 111H-16 de fabrication espagnole (2ème partie)" [Spanish Production of Heinkel He 111H-16s]. Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French). No. 43. pp. 22–27. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Arraez Cerda, Juan (November 1996). "Les Heinkel He 111H-16 de fabrication espagnole (3ème partie)". Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French). No. 44. pp. 19–21. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Arraez Cerda, Juan (December 1996). "Les Heinkel He 111H-16 de fabrication espagnole (dernière partie)". Avions: Toute l'aéronautique et son histoire (in French). No. 45. pp. 4–6. ISSN 1243-8650.

- de Zeng, H.L.; Stanket, D.G.; Creek, E.J. (2007). Bomber Units of the Luftwaffe 1933–1945: A Reference Source, Volume 1. London, UK: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-1857802795.

- de Zeng, H.L.; Stanket, D.G.; Creek, E.J. (2007). Bomber Units of the Luftwaffe 1933–1945: A Reference Source, Volume 2. London, UK: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-1903223871.

- Kober, Franz (1992). Heinkel He 111 Over all Fronts. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History. ISBN 978-0887403132.

- Marchand, Alain (September 1974). "Le Heinkel 111 français (I)" [The French Heinkel 111, Part 1]. Le Fana de l'Aviation (in French) (58): 12–16. ISSN 0757-4169.

- Smith, J. Richard; Kay, Anthony L. (2002). German Aircraft of the Second World War. Annapolis, Maryland: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 155750010X.

External links

[edit]- An article on an He 111 wreck site in Norway

- Video (Archive) of the Heinkel He 111 (D-AMUE) fitted with Walter RATO rocket boosters, third film of nine viewable Archived 26 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- YouTube 1997 Video of Commemorative Air Force's CASA-built He 111 with Merlin engines

- He 111 H3 WNr 6830, Virtual view of restoration to-date. Shot down in 1940, Recovered in northern Swedish lake 2008 Archived 4 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine

Heinkel He 111

View on GrokipediaThe Heinkel He 111 was a twin-engined medium bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934, initially disguised as a high-speed civil airliner to evade post-World War I Treaty of Versailles restrictions on German military aviation.[1][2] The prototype achieved its first flight on 24 February 1935, powered by BMW VI engines, and rapid development led to Luftwaffe acceptance by 1936, with early variants equipped with upgraded Daimler-Benz or Junkers powerplants.[1][2] As the Luftwaffe's primary medium bomber during the initial years of World War II, the He 111 participated in key operations including the Spanish Civil War with the Condor Legion from 1937, the invasion of Poland in 1939, the Battle of Britain in 1940, and extensive campaigns on the Eastern Front.[1][2] Over 7,000 units were produced between 1935 and 1944, predominantly the H-series fitted with Junkers Jumo 211 inverted V-12 engines delivering up to 1,300 horsepower each, enabling a maximum speed of 273 mph, a range of 1,430 miles, and a bomb load capacity exceeding 4,400 pounds internally plus external ordnance.[1][3] Defensive armament typically included up to seven 7.92 mm machine guns, supplemented by a 20 mm cannon or 13 mm gun in later models, operated by a crew of five.[1][2] Numerous variants emerged to adapt the design for diverse roles, such as the He 111J torpedo bomber, the He 111Z Zwilling twin-fuselage glider tug, and transport configurations, reflecting its versatility amid evolving wartime demands despite increasing vulnerability to Allied fighters by 1943.[1][3] Exported to allies including Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, and license-built in Spain as the CASA 2.111 which remained in service until the 1970s, the He 111 exemplified early German aviation engineering prowess but highlighted the Luftwaffe's doctrinal emphasis on medium bombers over strategic heavy types.[1][2]

Development History

Origins and Treaty Evasion

The Treaty of Versailles, imposed on Germany after World War I, strictly prohibited the development and production of military aircraft, including bombers, limiting aviation to civilian purposes. To circumvent these restrictions amid the Nazi regime's rearmament efforts following Adolf Hitler's ascension to power in January 1933, the Reich Air Ministry (RLM) secretly pursued advanced aircraft designs under the guise of civilian projects.[4] In late 1934, the RLM issued a specification for a versatile twin-engine monoplane capable of serving as a fast bomber (Schnellbomber) while outwardly designed as a civil airliner or mail plane to maintain plausible deniability.[4] Heinkel Flugzeugwerke, under Professor Ernst Heinkel, responded with the He 111 project, led by designers Siegfried and Walter Günter, emphasizing speed, elliptical wings for aerodynamic efficiency, and a streamlined fuselage to achieve performance comparable to contemporary fighters.[1] The design incorporated an all-metal stressed-skin construction, a departure from earlier fabric-covered aircraft, enabling higher speeds without defensive armament in initial configurations. The first prototype, He 111 V1 (civil registration D-ABHO), powered by two 660 hp (492 kW) BMW 132 radial engines, conducted its maiden flight on 24 February 1935 from Marienehe airfield near Rostock.[1] Subsequent prototypes, including V2 (D-ALIX) and V3 (D-ALES), tested refined features such as enclosed cockpits and alternative powerplants, while maintaining civilian markings to evade international scrutiny. A small production run of civil variants, designated He 111 C, was supplied to Deutsche Luft Hansa for passenger and mail services, with at least four units delivered by 1936, providing cover for military evaluation.[5] This dual-use approach allowed Heinkel to refine the design iteratively, transitioning it toward full military adoption as Versailles constraints weakened with Germany's withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933 and remilitarization announcements in 1935.[4]Prototypes and Early Testing