Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

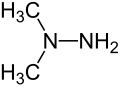

Hydrazines

View on Wikipedia| Alkylhydrazine (example) |

|

| Arylhydrazines (examples) |

|

|

|

|

Hydrazines (R2N−NR2) are a class of chemical compounds with two nitrogen atoms linked via a covalent bond and which carry from one up to four alkyl or aryl substituents. Hydrazines can be considered as derivatives of the inorganic hydrazine (H2N−NH2), in which one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by hydrocarbon groups.[1]

Production

[edit]- 1,1-Dimethylhydrazine is produced by the reduction of N-nitrosodimethylamine.[2]

- The reduction of benzenediazonium chloride with tin(II) chloride and hydrochloric acid provides phenylhydrazine.[2]

- 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine is produced by the reaction of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene with hydrazine.[2]

- Tetraphenylhydrazine is formed by the oxidation of diphenylamine with potassium permanganate in acetone.[2]

- Oxidation of a sulfamide rearranges it to a sulfonylhydrazide, which then hydrolyzes in acid to the hydrazine.[3]

Classification

[edit]Hydrazines can be divided into three groups according to the degree of substitution. Hydrazines belonging to the same group behave similarly in their chemical properties.

Monosubstituted hydrazines and so-called asymmetrically disubstituted hydrazines, where (only) two hydrocarbon groups are bonded to the same nitrogen atom, are colorless liquids. Such aliphatic hydrazines are very water soluble, strongly alkaline and good reducing agents. Aromatic monosubstituted and asymmetrically disubstituted hydrazines are poorly soluble in water, less basic and weaker reducing agents. For the preparation of aliphatic hydrazines, the reaction of hydrazine with alkylating compounds such as alkyl halides is used, or by reduction of nitroso derivatives. Aromatic hydrazines are prepared by reducing aromatic diazonium salts.[4][5]

Symmetric disubstituted hydrazines occur when a hydrocarbon group is bonded to each of the hydrazine nitrogen atoms. Like asymmetrically disubstituted hydrazines, they are liquids, but they boil at higher temperatures. In particular, the aliphatic compounds are basic and reducing agents and are soluble in water. Aromatic symmetric disubstituted hydrazines are not soluble in water. Symmetrically disubstituted hydrazines are prepared by reducing nitro compounds under basic conditions or by reducing the azines.

Tri- or tetrasubstituted aliphatic hydrazines are water-insoluble, weakly basic compounds. The corresponding arylhydrazines are solid colorless substances, insoluble in water and scarcely basic. They react with concentrated sulfuric acid to form violet or dark blue compounds.

History

[edit]Phenylhydrazine and 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine had been used historically in analytical chemistry to detect and identify compounds with carbonyl groups. Phenylhydrazine was used to study the structure of carbohydrates, because the reaction of the sugar's aldehyde groups lead to well crystallizing phenylhydrazones or osazones.

Examples

[edit]Organohydrazines and their derivatives are numerous, especially when hydrazones are included.

- monomethyl hydrazine, where one of the hydrogen atoms on the hydrazine molecule has been replaced with a methyl group (CH3). Due to the symmetry of the hydrazine molecule, it does not matter which hydrogen atom is replaced. It is sometimes used as a rocket fuel.

- 1,1-dimethylhydrazine (unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine, UDMH) and 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (symmetrical dimethylhydrazine) are hydrazines where two hydrogen atoms are replaced by methyl groups. UDMH is the easier of the two to manufacture and is a fairly common rocket fuel.

- gyromitrin and agaritine are hydrazine derivatives found in the commercially produced mushroom species Agaricus bisporus. Gyromitrin is metabolized into monomethyl hydrazine.

- Isoniazid, iproniazid, hydralazine, and phenelzine are medications whose molecules contain hydrazine-like structures.

- 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (2,4-DNPH) is commonly used to test for ketones and aldehydes in organic and clinical chemistry.

- phenylhydrazine, C6H5NHNH2, the first hydrazine to be discovered.

References

[edit]- ^ Nič, Miloslav; Jirát, Jiří; Košata, Bedřich; Jenkins, Aubrey; McNaught, Alan, eds. (2009-06-12). IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology: Gold Book (2.1.0 ed.). Research Triangle Park, NC: IUPAC. doi:10.1351/goldbook. ISBN 9780967855097.

- ^ a b c d Siegfried Hauptmann: Organische Chemie, 2. durchgesehene Auflage, VEB Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig, 1985, S. 522–523, ISBN 3-342-00280-8.

- ^ Ohme, R.; Preuschhof, H.; Heyne, H.-U. (1988). "Azoethane". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 6, p. 78.

- ^ Rothgery, Eugene F. (2004-11-19), "Hydrazine and Its Derivatives", in John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (ed.), Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., doi:10.1002/0471238961.0825041819030809.a01.pub2, ISBN 9780471238966

- ^ Schirmann, Jean-Pierre; Bourdauducq, Paul (2001-06-15), "Hydrazine", in Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA (ed.), Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_177, ISBN 9783527306732

Further reading

[edit]- Schmidt, Eckart W. (2022). "Alkylhydrazines". Encyclopedia of Liquid Fuels. De Gruyter. pp. 433–500. doi:10.1515/9783110750287-006. ISBN 978-3-11-075028-7.