Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

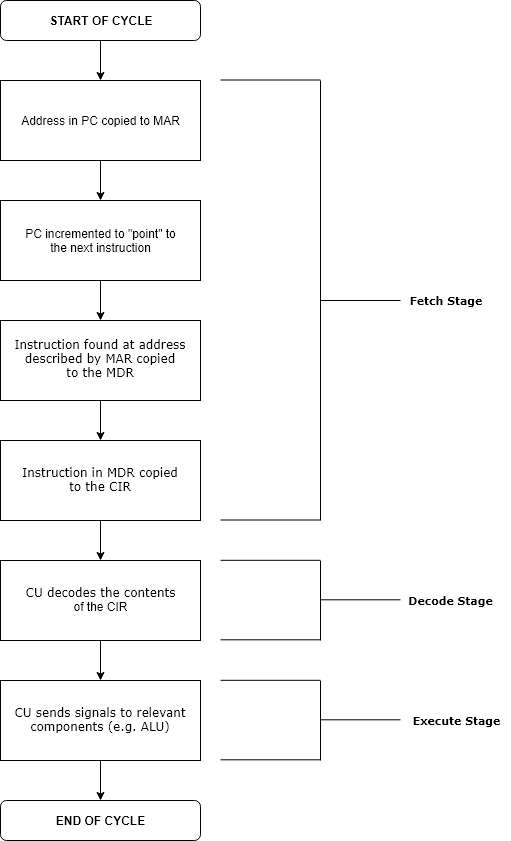

Instruction cycle

View on WikipediaThe instruction cycle (also known as the fetch–decode–execute cycle, or simply the fetch–execute cycle) is the cycle that the central processing unit (CPU) follows from boot-up until the computer has shut down in order to process instructions. It is composed of three main stages: the fetch stage, the decode stage, and the execute stage.

- PC – Program counter

- MAR – Memory address register

- MDR – Memory data register

- CIR – Current instruction register

- CU – Control unit

- ALU – Arithmetic logic unit

In simpler CPUs, the instruction cycle is executed sequentially, each instruction being processed before the next one is started. In most modern CPUs, the instruction cycles are instead executed concurrently, and often in parallel, through an instruction pipeline: the next instruction starts being processed before the previous instruction has finished, which is possible because the cycle is broken up into separate steps.[1]

Role of components

[edit]Program counter

[edit]The program counter (PC) is a register that holds the memory address of the next instruction to be executed. After each instruction copy to the memory address register (MAR), the PC can either increment the pointer to the next sequential instruction, jump to a specified pointer, or branch conditionally to a specified pointer.[2] Also, during a CPU halt, the PC holds the instruction being executed, until an external interrupt or a reset signal is received.

Memory address register

[edit]The MAR is responsible for storing the address describing the location of the instruction. After a read signal is initiated, the instruction in the address from the MAR is read and placed into the memory data register (MDR), also known as Memory Buffer Register (MBR). This component overall functions as an address buffer for pointing to locations in memory.

Memory data register

[edit]The MDR is responsible for temporarily holding instructions read from the address in MAR. It acts as a two-way register in the instruction cycle because it can take output from memory to the CPU, or output from the CPU to memory.

Current instruction register

[edit]The current instruction register (CIR, though sometimes referred to as the instruction register, IR) is where the instruction is temporarily held, for the CPU to decode it and produce correct control signals for the execution stage.

Control unit

[edit]The control unit (CU) decodes the instruction in the current instruction register (CIR). Then, the CU sends signals to other components within the CPU, such as the arithmetic logic unit (ALU), or back to memory to fetch operands, or to the floating-point unit (FPU). The ALU performs arithmetic operations based on specific opcodes in the instruction. For example, in RISC-V architecture, funct3 and funct7 opcodes exist to distinguish whether an instruction is a logical or arithmetic operation.

Summary of stages

[edit]Each computer's CPU can have different cycles based on different instruction sets, but will be similar to the following cycle:[3]

- Fetch stage: The fetch stage initiates the instruction cycle by retrieving the next instruction from memory. During this stage, the PC is polled for the address of the instruction in memory (using the MAR). Then the instruction is stored from the MDR into the CIR. At the end of this stage, the PC points to the next instruction that will be read at the next cycle.

- Decode stage: During this stage, the encoded instruction in the CIR is interpreted by the CU. It determines what operations and additional operands are required for execution and sends respective signals to respective components within the CPU, such as the ALU or FPU, to prepare for the execution of the instruction.

- Execute stage: This is the stage where the actual operation specified by the instruction is carried out by the relevant functional units of the CPU. Logical or arithmetic operations may be run by the ALU, data may be read from or written to memory, and the results are stored in registers or memory as required by the instruction. Based on output from the ALU, the PC might branch.

- Repeat cycle

In addition, on most processors, interrupts can occur. This will cause the CPU to jump to an interrupt service routine, execute that, and then return to the instruction it was meant to be executing. In some cases, the instruction can be interrupted in the middle, but there will be no effect, and the instruction will be re-executed after return from the interrupt.

Initiation

[edit]The first instruction cycle begins as soon as power is applied to the system, with an initial PC value that is predefined by the system's architecture (for instance, in Intel IA-32 CPUs, the predefined PC value is 0xfffffff0 whereas for ARM architecture CPUs, it is 0x00000000.) Typically, this address points to a set of instructions in read-only memory (ROM), which begins the process of loading (or booting) the operating system.[4]

Fetch stage

[edit]The fetch stage is the same for each instruction:

- The PC contains the address of the instruction to be fetched.

- This address is copied to the MAR, where this address is used to poll for the location of the instruction in memory.

- The CU sends a signal to the control bus to read the memory at the address in MAR - the data read is placed in the data bus.[5]

- The data is transferred to the CPU via the data bus, where it's loaded into the MDR - at this stage, the PC increments by one.

- The contents (instruction to-be-executed) of the MDR are copied into the CIR (where the instruction opcode and data operand can be decoded).

Decode stage

[edit]The decoding process allows the processor to determine what instruction is to be performed so that the CPU can tell how many operands it needs to fetch in order to perform the instruction. The opcode fetched from the memory is decoded for the next steps and moved to the appropriate registers. The decoding is typically performed by binary decoders in the CPU's CU.[6]

Determining effective addresses

[edit]There are various ways that an architecture can specify determining the address for operands, usually called the addressing modes.[7]

Some common ways the effective address can be found are:

- Direct addressing - the address of the instruction contains the effective address

- Indirect addressing - the address of the instruction specifies the address of the memory location that contains the effective address

- PC-relative addressing - the effective address is calculated from an address relative to the PC

- Stack addressing - the operand is at the top of the stack

Execute stage

[edit]The CPU sends the decoded instruction (decoded from the CU) as a set of control signals to corresponding components. Depending on the type of instruction, any of these can happen:

- Arithmetic/logical operations can be executed by the ALU (for example, ADD, SUB, AND, OR)[8]

- Read/writes from memory can be executed (for example, loading/storing bytes)

- Control flow alterations can be executed (for example, jumps or branches) - at this stage, if a jump were to occur, instead of the PC incrementing to the adjacent pointer, it would jump to the pointer specified in the instruction

This is the only stage of the instruction cycle that is useful from the perspective of the end-user. Everything else is overhead required to make the execute step happen.

See also

[edit]- Time slice, unit of operating system scheduling

- Classic RISC pipeline

- Complex instruction set computer

- Cycles per instruction

- Branch predictor

- Instruction set architecture

References

[edit]- ^ Crystal Chen, Greg Novick and Kirk Shimano (2000). "Pipelining". Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- ^ Dodge, N.B. (2017). "The Program Counter" (PDF). personal.utdallas.edu (Slides). Retrieved 2025-01-03.

- ^ Instruction Timing and Cycle (PDF).

- ^ Bosky Agarwal (2004). "Instruction Fetch Execute Cycle" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2009. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ Aryal, Er. Hari. Central Processing Unit (PDF).

- ^ Control Unit Operation (PDF).

- ^ Instruction Sets: Addressing Modes and Formats (PDF).

- ^ ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit) (PDF).