Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ionization

View on Wikipedia

Ionization or ionisation is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes. The resulting electrically charged atom or molecule is called an ion. Ionization can result from the loss of an electron after collisions with subatomic particles, collisions with other atoms, molecules, electrons, positrons,[1] protons, antiprotons,[2] and ions,[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] or through the interaction with electromagnetic radiation.[11] Heterolytic bond cleavage and heterolytic substitution reactions can result in the formation of ion pairs. Ionization can occur through radioactive decay by the internal conversion process, in which an excited nucleus transfers its energy to one of the inner-shell electrons causing it to be ejected.

Uses

[edit]Everyday examples of gas ionization occur within a fluorescent lamp or other electrical discharge lamps. It is also used in radiation detectors such as the Geiger-Müller counter or the ionization chamber. The ionization process is widely used in a variety of equipment in fundamental science (e.g., mass spectrometry) and in medical treatment (e.g., radiation therapy). It is also widely used for air purification, though studies have shown harmful effects of this application.[12][13]

Production of ions

[edit]

Negatively charged ions[14] are produced when a free electron collides with an atom and is subsequently trapped inside the electric potential barrier, releasing any excess energy. The process is known as electron capture ionization.

Positively charged ions are produced by transferring an amount of energy to a bound electron in a collision with charged particles (e.g. ions, electrons or positrons) or with photons. The threshold amount of the required energy is known as ionization energy. The study of such collisions is of fundamental importance with regard to the few-body problem, which is one of the major unsolved problems in physics. Kinematically complete experiments,[15] i.e. experiments in which the complete momentum vector of all collision fragments (the scattered projectile, the recoiling target-ion, and the ejected electron) are determined, have contributed to major advances in the theoretical understanding of the few-body problem in recent years.

Adiabatic ionization

[edit]Adiabatic ionization is a form of ionization in which an electron is removed from or added to an atom or molecule in its lowest energy state to form an ion in its lowest energy state.[16]

The Townsend discharge is a good example of the creation of positive ions and free electrons due to ion impact. It is a cascade reaction involving electrons in a region with a sufficiently high electric field in a gaseous medium that can be ionized, such as air. Following an original ionization event, due to such as ionizing radiation, the positive ion drifts towards the cathode, while the free electron drifts towards the anode of the device. If the electric field is strong enough, the free electron gains sufficient energy to liberate a further electron when it next collides with another molecule. The two free electrons then travel towards the anode and gain sufficient energy from the electric field to cause impact ionization when the next collisions occur; and so on. This is effectively a chain reaction of electron generation, and is dependent on the free electrons gaining sufficient energy between collisions to sustain the avalanche.[17]

Ionization efficiency is the ratio of the number of ions formed to the number of electrons or photons used.[18][19]

Ionization energy of atoms

[edit]

The trend in the ionization energy of atoms is often used to demonstrate the periodic behavior of atoms with respect to the atomic number, as summarized by ordering atoms in Mendeleev's table. This is a valuable tool for establishing and understanding the ordering of electrons in atomic orbitals without going into the details of wave functions or the ionization process. An example is presented in the figure to the right. The periodic abrupt decrease in ionization potential after rare gas atoms, for instance, indicates the emergence of a new shell in alkali metals. In addition, the local maximums in the ionization energy plot, moving from left to right in a row, are indicative of s, p, d, and f sub-shells.

Semi-classical description of ionization

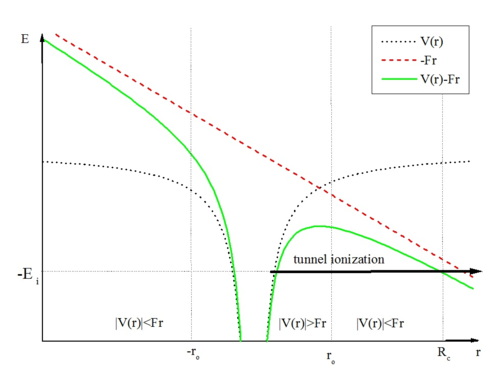

[edit]Classical physics and the Bohr model of the atom can qualitatively explain photoionization and collision-mediated ionization. In these cases, during the ionization process, the energy of the electron exceeds the energy difference of the potential barrier it is trying to pass. The classical description, however, cannot describe tunnel ionization since the process involves the passage of electron through a classically forbidden potential barrier.

Quantum mechanical description of ionization

[edit]The interaction of atoms and molecules with sufficiently strong laser pulses or with other charged particles leads to the ionization to singly or multiply charged ions. The ionization rate, i.e. the ionization probability in unit time, can be calculated using quantum mechanics. (There are classical methods available also, like the Classical Trajectory Monte Carlo Method (CTMC),[20][21] but it is not overall accepted and often criticized by the community.) There are two quantum mechanical methods exist, perturbative and non-perturbative methods like time-dependent coupled-channel or time independent close coupling[22] methods where the wave function is expanded in a finite basis set. There are numerous options available e.g. B-splines,[23] generalized Sturmians[24] or Coulomb wave packets.[25][26] Another non-perturbative method is to solve the corresponding Schrödinger equation fully numerically on a lattice.[27]

In general, the analytic solutions are not available, and the approximations required for manageable numerical calculations do not provide accurate enough results. However, when the laser intensity is sufficiently high, the detailed structure of the atom or molecule can be ignored and analytic solution for the ionization rate is possible.

Tunnel ionization

[edit]

Tunnel ionization is ionization due to quantum tunneling. In classical ionization, an electron must have enough energy to make it over the potential barrier, but quantum tunneling allows the electron simply to go through the potential barrier instead of going all the way over it because of the wave nature of the electron. The probability of an electron's tunneling through the barrier drops off exponentially with the width of the potential barrier. Therefore, an electron with a higher energy can make it further up the potential barrier, leaving a much thinner barrier to tunnel through and thus a greater chance to do so. In practice, tunnel ionization is observable when the atom or molecule is interacting with near-infrared strong laser pulses. This process can be understood as a process by which a bounded electron, through the absorption of more than one photon from the laser field, is ionized. This picture is generally known as multiphoton ionization (MPI).

Keldysh[28] modeled the MPI process as a transition of the electron from the ground state of the atom to the Volkov states.[29] In this model the perturbation of the ground state by the laser field is neglected and the details of atomic structure in determining the ionization probability are not taken into account. The major difficulty with Keldysh's model was its neglect of the effects of Coulomb interaction on the final state of the electron. As it is observed from figure, the Coulomb field is not very small in magnitude compared to the potential of the laser at larger distances from the nucleus. This is in contrast to the approximation made by neglecting the potential of the laser at regions near the nucleus. Perelomov et al.[30][31] included the Coulomb interaction at larger internuclear distances. Their model (which we call the PPT model) was derived for short range potential and includes the effect of the long range Coulomb interaction through the first order correction in the quasi-classical action. Larochelle et al.[32] have compared the theoretically predicted ion versus intensity curves of rare gas atoms interacting with a Ti:Sapphire laser with experimental measurement. They have shown that the total ionization rate predicted by the PPT model fit very well the experimental ion yields for all rare gases in the intermediate regime of the Keldysh parameter.

The rate of MPI on atom with an ionization potential in a linearly polarized laser with frequency is given by

where

- is the Keldysh parameter,

- ,

- is the peak electric field of the laser and

- .

The coefficients , and are given by

The coefficient is given by

where

Quasi-static tunnel ionization

[edit]The quasi-static tunneling (QST) is the ionization whose rate can be satisfactorily predicted by the ADK model,[33] i.e. the limit of the PPT model when approaches zero.[34] The rate of QST is given by

As compared to the absence of summation over n, which represent different above threshold ionization (ATI) peaks, is remarkable.

Strong field approximation for the ionization rate

[edit]The calculations of PPT are done in the E-gauge, meaning that the laser field is taken as electromagnetic waves. The ionization rate can also be calculated in A-gauge, which emphasizes the particle nature of light (absorbing multiple photons during ionization). This approach was adopted by Krainov model[35] based on the earlier works of Faisal[36] and Reiss.[37] The resulting rate is given by

where:

- with being the ponderomotive energy,

- is the minimum number of photons necessary to ionize the atom,

- is the double Bessel function,

- with the angle between the momentum of the electron, p, and the electric field of the laser, F,

- FT is the three-dimensional Fourier transform, and

- incorporates the Coulomb correction in the SFA model.

Population trapping

[edit]In calculating the rate of MPI of atoms only transitions to the continuum states are considered. Such an approximation is acceptable as long as there is no multiphoton resonance between the ground state and some excited states. However, in real situation of interaction with pulsed lasers, during the evolution of laser intensity, due to different Stark shift of the ground and excited states there is a possibility that some excited state go into multiphoton resonance with the ground state. Within the dressed atom picture, the ground state dressed by photons and the resonant state undergo an avoided crossing at the resonance intensity . The minimum distance, , at the avoided crossing is proportional to the generalized Rabi frequency, coupling the two states. According to Story et al.,[38] the probability of remaining in the ground state, , is given by

where is the time-dependent energy difference between the two dressed states. In interaction with a short pulse, if the dynamic resonance is reached in the rising or the falling part of the pulse, the population practically remains in the ground state and the effect of multiphoton resonances may be neglected. However, if the states go onto resonance at the peak of the pulse, where , then the excited state is populated. After being populated, since the ionization potential of the excited state is small, it is expected that the electron will be instantly ionized.

In 1992, de Boer and Muller [39] showed that Xe atoms subjected to short laser pulses could survive in the highly excited states 4f, 5f, and 6f. These states were believed to have been excited by the dynamic Stark shift of the levels into multiphoton resonance with the field during the rising part of the laser pulse. Subsequent evolution of the laser pulse did not completely ionize these states, leaving behind some highly excited atoms. We shall refer to this phenomenon as "population trapping".

We mention the theoretical calculation that incomplete ionization occurs whenever there is parallel resonant excitation into a common level with ionization loss.[40] We consider a state such as 6f of Xe which consists of 7 quasi-degnerate levels in the range of the laser bandwidth. These levels along with the continuum constitute a lambda system. The mechanism of the lambda type trapping is schematically presented in figure. At the rising part of the pulse (a) the excited state (with two degenerate levels 1 and 2) are not in multiphoton resonance with the ground state. The electron is ionized through multiphoton coupling with the continuum. As the intensity of the pulse is increased the excited state and the continuum are shifted in energy due to the Stark shift. At the peak of the pulse (b) the excited states go into multiphoton resonance with the ground state. As the intensity starts to decrease (c), the two state are coupled through continuum and the population is trapped in a coherent superposition of the two states. Under subsequent action of the same pulse, due to interference in the transition amplitudes of the lambda system, the field cannot ionize the population completely and a fraction of the population will be trapped in a coherent superposition of the quasi degenerate levels. According to this explanation the states with higher angular momentum – with more sublevels – would have a higher probability of trapping the population. In general the strength of the trapping will be determined by the strength of the two photon coupling between the quasi-degenerate levels via the continuum. In 1996, using a very stable laser and by minimizing the masking effects of the focal region expansion with increasing intensity, Talebpour et al.[41] observed structures on the curves of singly charged ions of Xe, Kr and Ar. These structures were attributed to electron trapping in the strong laser field. A more unambiguous demonstration of population trapping has been reported by T. Morishita and C. D. Lin.[42]

Non-sequential multiple ionization

[edit]The phenomenon of non-sequential ionization (NSI) of atoms exposed to intense laser fields has been a subject of many theoretical and experimental studies since 1983. The pioneering work began with the observation of a "knee" structure on the Xe2+ ion signal versus intensity curve by L'Huillier et al.[43] From the experimental point of view, the NS double ionization refers to processes which somehow enhance the rate of production of doubly charged ions by a huge factor at intensities below the saturation intensity of the singly charged ion. Many, on the other hand, prefer to define the NSI as a process by which two electrons are ionized nearly simultaneously. This definition implies that apart from the sequential channel there is another channel which is the main contribution to the production of doubly charged ions at lower intensities. The first observation of triple NSI in argon interacting with a 1 μm laser was reported by Augst et al.[44] Later, systematically studying the NSI of all rare gas atoms, the quadruple NSI of Xe was observed.[45] The most important conclusion of this study was the observation of the following relation between the rate of NSI to any charge state and the rate of tunnel ionization (predicted by the ADK formula) to the previous charge states;

where is the rate of quasi-static tunneling to i'th charge state and are some constants depending on the wavelength of the laser (but not on the pulse duration).

Two models have been proposed to explain the non-sequential ionization; the shake-off model and electron re-scattering model. The shake-off (SO) model, first proposed by Fittinghoff et al.,[46] is adopted from the field of ionization of atoms by X rays and electron projectiles where the SO process is one of the major mechanisms responsible for the multiple ionization of atoms. The SO model describes the NSI process as a mechanism where one electron is ionized by the laser field and the departure of this electron is so rapid that the remaining electrons do not have enough time to adjust themselves to the new energy states. Therefore, there is a certain probability that, after the ionization of the first electron, a second electron is excited to states with higher energy (shake-up) or even ionized (shake-off). We should mention that, until now, there has been no quantitative calculation based on the SO model, and the model is still qualitative.

The electron rescattering model was independently developed by Kuchiev,[47] Schafer et al,[48] Corkum,[49] Becker and Faisal[50] and Faisal and Becker.[51] The principal features of the model can be understood easily from Corkum's version. Corkum's model describes the NS ionization as a process whereby an electron is tunnel ionized. The electron then interacts with the laser field where it is accelerated away from the nuclear core. If the electron has been ionized at an appropriate phase of the field, it will pass by the position of the remaining ion half a cycle later, where it can free an additional electron by electron impact. Only half of the time the electron is released with the appropriate phase and the other half it never return to the nuclear core. The maximum kinetic energy that the returning electron can have is 3.17 times the ponderomotive potential () of the laser. Corkum's model places a cut-off limit on the minimum intensity ( is proportional to intensity) where ionization due to re-scattering can occur.

The re-scattering model in Kuchiev's version (Kuchiev's model) is quantum mechanical. The basic idea of the model is illustrated by Feynman diagrams in figure a. First both electrons are in the ground state of an atom. The lines marked a and b describe the corresponding atomic states. Then the electron a is ionized. The beginning of the ionization process is shown by the intersection with a sloped dashed line. where the MPI occurs. The propagation of the ionized electron in the laser field, during which it absorbs other photons (ATI), is shown by the full thick line. The collision of this electron with the parent atomic ion is shown by a vertical dotted line representing the Coulomb interaction between the electrons. The state marked with c describes the ion excitation to a discrete or continuum state. Figure b describes the exchange process. Kuchiev's model, contrary to Corkum's model, does not predict any threshold intensity for the occurrence of NS ionization.

Kuchiev did not include the Coulomb effects on the dynamics of the ionized electron. This resulted in the underestimation of the double ionization rate by a huge factor. Obviously, in the approach of Becker and Faisal (which is equivalent to Kuchiev's model in spirit), this drawback does not exist. In fact, their model is more exact and does not suffer from the large number of approximations made by Kuchiev. Their calculation results perfectly fit with the experimental results of Walker et al.[52] Becker and Faisal[53] have been able to fit the experimental results on the multiple NSI of rare gas atoms using their model. As a result, the electron re-scattering can be taken as the main mechanism for the occurrence of the NSI process.

Multiphoton ionization of inner-valence electrons and fragmentation of polyatomic molecules

[edit]The ionization of inner valence electrons are responsible for the fragmentation of polyatomic molecules in strong laser fields. According to a qualitative model[54][55] the dissociation of the molecules occurs through a three-step mechanism:

- MPI of electrons from the inner orbitals of the molecule which results in a molecular ion in ro-vibrational levels of an excited electronic state;

- Rapid radiationless transition to the high-lying ro-vibrational levels of a lower electronic state; and

- Subsequent dissociation of the ion to different fragments through various fragmentation channels.

The short pulse induced molecular fragmentation may be used as an ion source for high performance mass spectroscopy. The selectivity provided by a short pulse based source is superior to that expected when using the conventional electron ionization based sources, in particular when the identification of optical isomers is required.[56][57]

Kramers–Henneberger frame

[edit]The Kramers–Henneberger(KF) frame is the non-inertial frame moving with the free electron under the influence of the harmonic laser pulse, obtained by applying a translation to the laboratory frame equal to the quiver motion of a classical electron in the laboratory frame. In other words, in the Kramers–Henneberger frame the classical electron is at rest.[60] Starting in the lab frame (velocity gauge), we may describe the electron with the Hamiltonian:

In the dipole approximation, the quiver motion of a classical electron in the laboratory frame for an arbitrary field can be obtained from the vector potential of the electromagnetic field:

where for a monochromatic plane wave.

By applying a transformation to the laboratory frame equal to the quiver motion one moves to the 'oscillating' or 'Kramers–Henneberger' frame, in which the classical electron is at rest. By a phase factor transformation for convenience one obtains the 'space-translated' Hamiltonian, which is unitarily equivalent to the lab-frame Hamiltonian, which contains the original potential centered on the oscillating point :

The utility of the KH frame lies in the fact that in this frame the laser-atom interaction can be reduced to the form of an oscillating potential energy, where the natural parameters describing the electron dynamics are and (sometimes called the "excursion amplitude', obtained from ).

From here one can apply Floquet theory to calculate quasi-stationary solutions of the TDSE. In high frequency Floquet theory, to lowest order in the system reduces to the so-called 'structure equation', which has the form of a typical energy-eigenvalue Schrödinger equation containing the 'dressed potential' (the cycle-average of the oscillating potential). The interpretation of the presence of is as follows: in the oscillating frame, the nucleus has an oscillatory motion of trajectory and can be seen as the potential of the smeared out nuclear charge along its trajectory.

The KH frame is thus employed in theoretical studies of strong-field ionization and atomic stabilization (a predicted phenomenon in which the ionization probability of an atom in a high-intensity, high-frequency field actually decreases for intensities above a certain threshold) in conjunction with high-frequency Floquet theory.[61]

The KF frame was successfully applied for different problems as well e.g. for higher-hamonic generation from a metal surface in a powerful laser field[62]

Dissociation – distinction

[edit]A substance may dissociate without necessarily producing ions. As an example, the molecules of table sugar dissociate in water (sugar is dissolved) but exist as intact neutral entities. Another subtle event is the dissociation of sodium chloride (table salt) into sodium and chlorine ions. Although it may seem as a case of ionization, in reality the ions already exist within the crystal lattice. When salt is dissociated, its constituent ions are simply surrounded by water molecules and their effects are visible (e.g. the solution becomes electrolytic). However, no transfer or displacement of electrons occurs.

Table

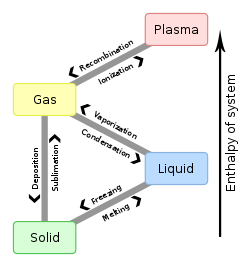

[edit]To From

|

Solid | Liquid | Gas | Plasma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Melting | Sublimation | ||

| Liquid | Freezing | Vaporization | ||

| Gas | Deposition | Condensation | Ionization | |

| Plasma | Recombination |

See also

[edit]- Above threshold ionization

- Double ionization

- Chemical ionization

- Electron ionization

- Ionization chamber – Instrument for detecting gaseous ionization, used in ionizing radiation measurements

- Ion source

- Photoionization

- Thermal ionization

- Townsend avalanche – The chain reaction of ionization occurring in a gas with an applied electric field

- Poole–Frenkel effect

References

[edit]- ^ Machacek, J.R.; McEachran, R.P.; Stauffer, A.D. (2023). "Positron Collisions". Springer Handbook of Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics. Springer Handbooks. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-73893-8_51. ISBN 978-3-030-73892-1.

- ^ Kirchner, Tom; Knudsen, Helge (2011). "Current status of antiproton impact ionization of atoms and molecules: theoretical and experimental perspectives". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 44 (12) 122001. Bibcode:2011JPhB...44l2001K. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/44/12/122001.

- ^ Brandsen, B.H. (1970). Atomic Collision Theory. Benjamin. ISBN 978-0-8053-1180-8.

- ^ Stolterfoht, N; DuBois, R.D.; Rivarola, R.D. (1997). Electron Emission in Heavy Ion-Atom Collisions. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-08322-8.

- ^ McGuire, J.H. (1997). Electron correlation dynamics in atomic collisions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48020-8.

- ^ Eichler, J. (2005). Lectures on Ion-Atom Collisions: From Nonrelativistic to Relativistic Velocities. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-52047-0.

- ^ Bransden, B.H.; McDowell, M.R.C. (1992). Charge Exchange and the Theory of Ion-Atom Collisions. Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852020-7.

- ^ Janev, R.K.; Presnyakov, L.P.; Shevelko, V.P. (1985). Physics of Highly Charged Ions. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-69197-3.

- ^ Schulz, Michael (2019). Schulz, Michael (ed.). Ion-Atom Collisions The Few-Body Problem in Dynamic Systems. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110580297. ISBN 978-3-11-057942-0.

- ^ D., Belkic (2009). Quantum Theory of High-Energy Ion-Atom Collisions. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-58488-728-7.

- ^ Schmelcher, P.; Schweitzer, W. (2002). Atoms and Molecules in Strong External Fields. Kulver Academic Publishers. ISBN 0-306-45811-X.

- ^ Waring, M. S.; Siegel, J. A. (August 2011). "The effect of an ion generator on indoor air quality in a residential room: Effect of an ion generator on indoor air in a room". Indoor Air. 21 (4): 267–276. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2010.00696.x. PMID 21118308.

- ^ University, Colorado State. "Study uncovers safety concerns with ionic air purifiers". phys.org. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Andersen, T (2004). "Atomic negative ions: structure, dynamics and collisions". Physics Reports. 394 (4–5): 157–313. Bibcode:2004PhR...394..157A. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2004.01.001 – via 157-313.

- ^ Schulz, Michael (2003). "Three-Dimensional Imaging of Atomic Four-Body Processes". Nature. 422 (6927): 48–51. Bibcode:2003Natur.422...48S. doi:10.1038/nature01415. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0011-8F36-A. PMID 12621427. S2CID 4422064.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "adiabatic ionization". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00143

- ^ Glenn F Knoll. Radiation Detection and Measurement, third edition 2000. John Wiley and sons, ISBN 0-471-07338-5

- ^ Todd, J. F. J. (1991). "Recommendations for Nomenclature and Symbolism for Mass Spectroscopy (including an appendix of terms used in vacuum technology)(IUPAC Recommendations 1991)". Pure Appl. Chem. 63 (10): 1541–1566. doi:10.1351/pac199163101541.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "ionization efficiency". doi:10.1351/goldbook.I03196

- ^ Abrines, R.; Percival, I.C. (1966). "Classical theory of charge transfer and ionization of hydrogen atoms by protons". Proceedings of the Physical Society. 88 (4): 861–872. Bibcode:1966PPS....88..861A. doi:10.1088/0370-1328/88/4/306.

- ^ Schultz, D.R. (1989). "Comparison of single-electron removal processes in collisions of electrons, positrons, protons, and antiprotons with hydrogen and helium". Phys. Rev. A. 41 (5): 2330–2334. Bibcode:1989PhRvA..40.2330S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.40.2330. PMID 9902408.

- ^ Abdurakhmanov, I.B.; Plowman, C; Kadyrov, A.S.; Bray, I.; Mukhamedzhanov, A.M. (2020). "One-center close-coupling approach to two-center rearrangement collisions". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 53 (14): 145201. Bibcode:2020JPhB...53n5201A. doi:10.1088/1361-6455/ab894a. OSTI 1733342.

- ^ Martin, Fernando (1999). "Ionization and dissociation using B-splines: photoionization of the hydrogen molecule". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 32 (16): R197 – R231. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/32/16/201.

- ^ Avery, J. (2006). Generalized Sturmians And Atomic Spectra. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 981-256-806-9.

- ^ Barna, I.F.; Grün, N.; Scheid, W. (2003). "Coupled-channel study with Coulomb wave packets for ionization of helium in heavy ion collisions". European Physical Journal D. 25 (3): 239–246. Bibcode:2003EPJD...25..239B. doi:10.1140/epjd/e2003-00206-6.

- ^ Abdurakhmanov, I.B.; Kadyrov, A.S.; Bray, I; Bartschat, K. (2017). "Wave-packet continuum-discretization approach to single ionization of helium by antiprotons and energetic protons". Phys. Rev. A. 96 (2) 022702. Bibcode:2017PhRvA..96b2702A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.96.022702. hdl:10072/409310.

- ^ Schultz, D.R.; Krstic, P.S. (2003). "Ionization of helium by antiprotons: Fully correlated, four-dimensional lattice approach". Physical Review A. 67 (2) 022712. Bibcode:2003PhRvA..67b2712S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.67.022712.

- ^ Keldysh, L. V. (1965). "Ionization in the Field of a Strong Electromagnetic Wave". Soviet Phys. JETP. 20 (5): 1307.

- ^ Volkov D M 1934 Z. Phys. 94 250

- ^ Perelomov, A. M.; Popov, V. S.; Terent'ev, M. V. (1966). "Ionization of Atoms in an Alternating Electric Field". Soviet Phys. JETP. 23 (5): 924. Bibcode:1966JETP...23..924P. Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ^ Perelomov, A. M.; Popov, V. S.; Terent'ev, M. V. (1967). "Ionization of Atoms in an Alternating Electric Field: II". Soviet Phys. JETP. 24 (1): 207. Bibcode:1967JETP...24..207P. Archived from the original on 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ^ Larochelle, S.; Talebpour, A.; Chin, S. L. (1998). "Coulomb effect in multiphoton ionization of rare-gas atoms" (PDF). Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 31 (6): 1215. Bibcode:1998JPhB...31.1215L. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/31/6/009. S2CID 250870476. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 21, 2014.

- ^ Ammosov, M. V.; Delone, N. B.; Krainov, V. P. (1986). "Tunnel ionization of complex atoms and of atomic ions in an alternating electromagnetic field". Soviet Phys. JETP. 64 (6): 1191. Bibcode:1986JETP...64.1191A. Archived from the original on 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ^ Sharifi, S. M.; Talebpour, A; Yang, J.; Chin, S. L. (2010). "Quasi-static tunnelling and multiphoton processes in the ionization of Ar and Xe using intense femtosecond laser pulses". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 43 (15) 155601. Bibcode:2010JPhB...43o5601S. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/43/15/155601. ISSN 0953-4075. S2CID 121014268.

- ^ Krainov, Vladimir P. (1997). "Ionization rates and energy and angular distributions at the barrier-suppression ionization of complex atoms and atomic ions". Journal of the Optical Society of America B. 14 (2): 425. Bibcode:1997JOSAB..14..425K. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.14.000425. ISSN 0740-3224.

- ^ Faisal, F. H. M. (1973). "Multiple absorption of laser photons by atoms". Journal of Physics B: Atomic and Molecular Physics. 6 (4): L89 – L92. Bibcode:1973JPhB....6L..89F. doi:10.1088/0022-3700/6/4/011. ISSN 0022-3700.

- ^ Reiss, Howard (1980). "Effect of an intense electromagnetic field on a weakly bound system". Physical Review A. 22 (5): 1786–1813. Bibcode:1980PhRvA..22.1786R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.22.1786. ISSN 0556-2791.

- ^ Story, J.; Duncan, D.; Gallagher, T. (1994). "Landau-Zener treatment of intensity-tuned multiphoton resonances of potassium". Physical Review A. 50 (2): 1607–1617. Bibcode:1994PhRvA..50.1607S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.50.1607. ISSN 1050-2947. PMID 9911054.

- ^ De Boer, M.; Muller, H. (1992). "Observation of large populations in excited states after short-pulse multiphoton ionization". Physical Review Letters. 68 (18): 2747–2750. Bibcode:1992PhRvL..68.2747D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.2747. PMID 10045482.

- ^ Hioe, F. T.; Carrol, C. E. (1988). "Coherent population trapping in N-level quantum systems". Physical Review A. 37 (8): 3000–3005. Bibcode:1988PhRvA..37.3000H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.37.3000. PMID 9900034.

- ^ Talebpour, A.; Chien, C. Y.; Chin, S. L. (1996). "Population trapping in rare gases". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 29 (23): 5725. Bibcode:1996JPhB...29.5725T. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/29/23/015. S2CID 250757252.

- ^ Morishita, Toru; Lin, C. D. (2013). "Photoelectron spectra and high Rydberg states of lithium generated by intense lasers in the over-the-barrier ionization regime" (PDF). Physical Review A. 87 (6) 63405. Bibcode:2013PhRvA..87f3405M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.87.063405. hdl:2097/16373. ISSN 1050-2947.

- ^ L'Huillier, A.; Lompre, L. A.; Mainfray, G.; Manus, C. (1983). "Multiply charged ions induced by multiphoton absorption in rare gases at 0.53 μm". Physical Review A. 27 (5): 2503. Bibcode:1983PhRvA..27.2503L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.27.2503.

- ^ Augst, S.; Talebpour, A.; Chin, S. L.; Beaudoin, Y.; Chaker, M. (1995). "Nonsequential triple ionization of argon atoms in a high-intensity laser field". Physical Review A. 52 (2): R917 – R919. Bibcode:1995PhRvA..52..917A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.52.R917. PMID 9912436.

- ^ Larochelle, S.; Talebpour, A.; Chin, S. L. (1998). "Non-sequential multiple ionization of rare gas atoms in a Ti:Sapphire laser field". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 31 (6): 1201. Bibcode:1998JPhB...31.1201L. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/31/6/008. S2CID 250747225.

- ^ Fittinghoff, D. N.; Bolton, P. R.; Chang, B.; Kulander, K. C. (1992). "Observation of nonsequential double ionization of helium with optical tunneling". Physical Review Letters. 69 (18): 2642–2645. Bibcode:1992PhRvL..69.2642F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.2642. PMID 10046547.

- ^ [1]Kuchiev, M. Yu (1987). "Atomic antenna". Soviet Phys. JETP Lett. 45: 404–406.

- ^ Schafer, K. J.; Yang, B.; DiMauro, L.F.; Kulander, K.C. (1992). "Above threshold ionization beyond the high harmonic cutoff". Physical Review Letters. 70 (11): 1599–1602. Bibcode:1993PhRvL..70.1599S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.1599. PMID 10053336.

- ^ Corkum, P. B. (1993). "Plasma perspective on strong field multiphoton ionization". Physical Review Letters. 71 (13): 1994–1997. Bibcode:1993PhRvL..71.1994C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.1994. PMID 10054556. S2CID 29947935.

- ^ Becker, Andreas; Faisal, Farhad H M (1996). "Mechanism of laser-induced double ionization of helium". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 29 (6): L197 – L202. Bibcode:1996JPhB...29L.197B. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/29/6/005. ISSN 0953-4075. S2CID 250808704.

- ^ [2]Faisal, F. H. M.; Becker, A. (1997). "Nonsequential double ionization: Mechanism and model formula". Laser Phys. 7: 684.

- ^ Walker, B.; Sheehy, B.; Dimauro, L. F.; Agostini, P.; Schafer, K. J.; Kulander, K. C. (1994). "Precision Measurement of Strong Field Double Ionization of Helium". Physical Review Letters. 73 (9): 1227–1230. Bibcode:1994PhRvL..73.1227W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.1227. PMID 10057657.

- ^ Becker, A.; Faisal, F. H. M. (1999). "S-matrix analysis of ionization yields of noble gas atoms at the focus of Ti:sapphire laser pulses". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 32 (14): L335. Bibcode:1999JPhB...32L.335B. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/32/14/101. S2CID 250766534.

- ^ Talebpour, A.; Bandrauk, A. D.; Yang, J; Chin, S. L. (1999). "Multiphoton ionization of inner-valence electrons and fragmentation of ethylene in an intense Ti:sapphire laser pulse" (PDF). Chemical Physics Letters. 313 (5–6): 789. Bibcode:1999CPL...313..789T. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(99)01075-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 21, 2014.

- ^ Talebpour, A; Bandrauk, A D; Vijayalakshmi, K; Chin, S L (2000). "Dissociative ionization of benzene in intense ultra-fast laser pulses". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 33 (21): 4615. Bibcode:2000JPhB...33.4615T. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/33/21/307. S2CID 250738396.

- ^ Mehdi Sharifi, S.; Talebpour, A.; Chin, S. L. (2008). "Ultra-fast laser pulses provide an ion source for highly selective mass spectroscopy". Applied Physics B. 91 (3–4): 579. Bibcode:2008ApPhB..91..579M. doi:10.1007/s00340-008-3038-y. S2CID 122546433.

- ^ Peng, Jiahui; Puskas, Noah; Corkum, Paul B.; Rayner, David M.; Loboda, Alexandre V. (2012). "High-Pressure Gas Phase Femtosecond Laser Ionization Mass Spectrometry". Analytical Chemistry. 84 (13): 5633–5640. doi:10.1021/ac300743k. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 22670784. S2CID 10780362.

- ^ Kramers, H.A. (1956). Collected Papers. North Holland.

- ^ Henneberger, W.C. (1968). "Perturbation Method for Atoms in Intense Light Beams". Physical Review Letters. 21 (12): 838. Bibcode:1968PhRvL..21..838H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.21.838.

- ^ Gavrila, Mihai (2002-09-28). "Atomic stabilization in superintense laser fields". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 35 (18): R147 – R193. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/35/18/201. ISSN 0953-4075.

- ^ Gavrila, Mihai. "Atomic structure and decay in high-frequency fields." Atoms in Intense Laser Fields, edited by Mihai Gavrila, Academic Press, Inc, 1992, pp. 435-508.

- ^ Varró, S.; Ehlotzky, F. (1994). "Higher-harmonic generation from a metal surface in a powerful laser field". Physical Review A. 49 (3): 3106. Bibcode:1994PhRvA..49.3106V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.49.3106. PMID 9910600.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of ionization at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of ionization at Wiktionary

Ionization

View on GrokipediaBasic Concepts

Definition and Types

Ionization is the physical process by which an atom, molecule, or ion acquires a net electric charge by either losing one or more electrons to form positively charged cations or gaining electrons to form negatively charged anions.[1] This process disrupts the electrical neutrality of the species involved, often requiring the input of energy to overcome the binding forces of the electrons. A fundamental representation of ionization is the reaction where a neutral atom or molecule A absorbs energy to eject an electron, yielding a cation and a free electron:[10] In some cases, ionization can produce ion pairs, where both a cation and an anion are formed simultaneously, such as through the interaction of high-energy particles or radiation with neutral species.[2] Ionization can be classified into several primary types based on the mechanism and number of electrons involved. Single ionization refers to the removal of one electron from the neutral species, which is the most common form and occurs in various energy-input scenarios.[11] Multiple ionization involves the removal of two or more electrons, which can proceed sequentially—where electrons are ejected one at a time in successive steps—or non-sequentially, involving correlated electron dynamics in intense fields.[12] Key subtypes include thermal ionization, where high temperatures provide the energy to overcome electron binding in gases or vapors; photoionization, triggered by the absorption of photons with sufficient energy to eject electrons; and field ionization, induced by strong electric fields that promote electron tunneling from the atomic or molecular orbital.[13][14] Ionization manifests in diverse contexts across physical states, influencing material properties and phenomena. In gases, it leads to the formation of plasmas, which are partially or fully ionized states consisting of free electrons, ions, and neutrals that enable electrical conductivity and collective behaviors.[15] In aqueous solutions, ionization of electrolytes produces dissociated ions that facilitate conduction, as seen in salts like sodium chloride dissociating into Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions.[11] In solids, particularly semiconductors, processes like impact ionization generate charge carriers by energetic electrons colliding with lattice atoms, enabling applications in electronics.[16] The foundational understanding of ionization traces back to J.J. Thomson's 1897 experiments on cathode rays in partially evacuated tubes, where he observed gas ionization and measured the charge-to-mass ratio of electrons, leading to their discovery.[17]

Ionization Energy

Ionization energy is defined as the minimum energy required to remove an electron from a gaseous atom or ion in its ground state.[18] The first ionization energy (IE₁) refers to the removal of the most loosely bound electron from a neutral atom, while successive ionization energies (IE₂, IE₃, etc.) correspond to removing additional electrons from the resulting cation.[19] These successive energies increase progressively because, after the initial electron removal, the remaining electrons experience a higher effective nuclear charge (Z_eff), as there is less electronic shielding from the nucleus.[20] In the periodic table, ionization energies exhibit clear trends: they generally decrease down a group due to increasing atomic radius and greater shielding by inner electrons, which reduces Z_eff for valence electrons, and increase across a period from left to right as Z_eff rises without a corresponding increase in shielding.[18] Notable exceptions occur, such as the decrease between group 2 and group 13 elements (e.g., from beryllium to boron), where the electron configuration allows removal from a higher-energy p orbital rather than a stable s orbital.[21] Ionization energies are typically measured using techniques like photoelectron spectroscopy, which determines electron binding energies from the kinetic energy of ejected photoelectrons, or atomic spectroscopy, which observes spectral lines corresponding to ionization thresholds; values are expressed in electron volts (eV) or kilojoules per mole (kJ/mol).[22] For molecules, ionization energy relates to molecular orbital (MO) theory, where the energy required approximates the negative of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energy according to Koopmans' theorem, assuming no electron rearrangement. Two key types are distinguished: adiabatic ionization energy, the minimum energy for transition between relaxed ground states of the neutral and ion (accounting for geometry changes), and vertical ionization energy, which assumes instantaneous electron removal without nuclear motion, governed by the Franck-Condon principle.[23] In photoelectron spectroscopy, the ionization energy is calculated as IE = hν - KE, where hν is the incident photon energy and KE is the measured kinetic energy of the ejected electron; for atomic hydrogen, this yields IE₁ = 13.6 eV, corresponding to excitation from its ground state energy of -13.6 eV to the ionized state at 0 eV.[22][24] Ionization energies correlate with other atomic properties, such as electronegativity, which often scales with IE due to the atom's tendency to attract electrons in bonds (e.g., Mulliken electronegativity is (IE + EA)/2, where EA is electron affinity), and electron affinity, as both reflect the stability of electron removal or addition.[25]Production Mechanisms

Thermal and Adiabatic Processes

Thermal ionization refers to the process by which atoms or molecules in a gas acquire sufficient thermal energy through collisions to overcome their ionization energy, resulting in the formation of ions and free electrons, typically in a state of thermal equilibrium. This mechanism dominates in high-temperature environments where the kinetic energy distribution follows a Maxwell-Boltzmann profile, enabling electron-impact ionization. In such systems, the equilibrium ionization state is governed by the balance between ionization and recombination rates, leading to a predictable distribution of ionization stages based on temperature and density.[26] The Saha equation quantifies this equilibrium for a plasma, relating the densities of consecutive ionization stages to temperature. For the transition from ionization stage to , it is expressed as where , , and are the number densities of the ions in stages and and free electrons, respectively; and are the statistical weights of the respective states; is the electron mass; is Boltzmann's constant; is the temperature; is Planck's constant; and is the ionization energy from stage to . This equation assumes local thermodynamic equilibrium and neglects interactions beyond binary collisions. Derived from statistical mechanics and detailed balance principles, it applies to dilute gases where pressure effects are minimal.[27][28] In astrophysical contexts, the Saha equation accurately predicts ionization in stellar atmospheres, such as the high degree of ionization in the solar corona, where temperatures exceed 1 MK lead to nearly complete stripping of hydrogen and helium. Similarly, in laboratory arc discharges, thermal ionization sustains conductive plasmas at temperatures around 5000–10,000 K, facilitating applications in welding and lighting. However, at high densities (above ~10^{18} cm^{-3}), the assumption of equilibrium breaks down due to enhanced three-body recombination, where an ion-electron pair recombines in the presence of a third body, absorbing excess energy and suppressing net ionization. This limits the applicability of the Saha equation in dense, optically thick plasmas.[29][30] Ionization in adiabatic processes occurs in gases where energy is added or removed without heat exchange with the surroundings, maintaining constant entropy. This includes reversible compression or expansion that changes temperature and pressure, thereby shifting the ionization balance. For example, in astrophysical outflows, adiabatic expansion leads to cooling and recombination, while initial compression phases can drive ionization. This mechanism is relevant in systems without rapid non-thermal energy inputs, allowing the gas to follow thermodynamic equilibrium paths.[31] Practical examples include ionization in flame spectroscopy, where alkali metals like sodium ionize thermally at flame temperatures of 1500–2500 K, enhancing emission signals for trace analysis. In thermionic energy converters, used in thermoelectric generators, thermal ionization emits electrons from a hot cathode (around 2000 K), generating current across a vacuum gap for power conversion. Historically, Irving Langmuir's studies in the 1920s on gas discharges and thermionic phenomena at General Electric laid foundational insights into plasma behavior, including equilibrium ionization in heated vapors, influencing modern plasma applications.[32][33][34] For non-equilibrium conditions, the ionization rate is described by rate equations, where the net ionization rate for stage is , with the ionization rate coefficient and the recombination coefficient. The thermal collision ionization rate coefficient for electron-impact is derived from the collision cross-section , where is the electron energy, via the Maxwellian average: with velocity and Maxwellian distribution . This integral is evaluated using empirical or quantum cross-sections, often approximated for thresholds near by forms like the Seaton expression, cm³/s for hydrogen-like atoms, ensuring detailed balance with recombination in equilibrium via from the Saha equation. Such derivations underpin time-dependent modeling in transient plasmas.[26][35]Impact Ionization

Impact ionization occurs through collisions between energetic charged particles, such as electrons or ions, and neutral atoms or molecules, where the incident particle transfers sufficient energy to eject an electron, creating an ion pair. This process is prominent in non-equilibrium conditions, such as in gas discharges, semiconductors, and radiation detectors, and can lead to avalanche effects where newly freed electrons further ionize, amplifying the initial event. The probability is governed by the impact ionization cross section , which is zero below the threshold energy (equal to the ionization potential) and rises sharply thereafter, often modeled by forms like the Lotz formula or quantum calculations. For electron-impact, the differential cross section depends on the kinematics, with energy and momentum conservation determining the ejected electron's energy. In gases, the Townsend avalanche coefficient quantifies the number of ionizations per unit path length: , where is neutral density, the electron energy distribution, and the drift velocity. This leads to breakdown when for gap distance .[5] Applications include gas-filled detectors like Geiger-Müller counters, where impact ionization sustains the discharge pulse, and in semiconductor avalanche photodiodes for low-light detection. In astrophysics, cosmic ray impacts ionize interstellar media.[4]Chemical Ionization

Chemical ionization involves the interaction of neutral molecules with pre-existing ions or reactive species, leading to charge transfer or protonation/deprotonation without direct electron removal by photons or fields. This soft ionization technique minimizes fragmentation, preserving molecular identity, and is widely used in mass spectrometry. In a typical setup, reagent gases like methane produce reactant ions (e.g., CH₅⁺ or C₂H₅⁺) via electron-impact, which then react with analytes: e.g., A + CH₅⁺ → AH⁺ + CH₄ (proton transfer if proton affinity of A > methane). The rate constants follow Langevin capture theory for ion-molecule collisions, , where is ion charge, polarizability, reduced mass. Exothermic reactions proceed near the collision rate, while endothermic ones are suppressed. Developed by Field and Munson in 1965, it contrasts with hard ionization methods by producing abundant [M+H]⁺ or [M-H]⁻ ions.[3] This method is essential for analyzing thermally labile compounds in environmental and biological samples, with minimal excess energy (~1-5 eV) compared to electron ionization (~70 eV).[8]Photoionization Processes

Photoionization is the process by which an atom or molecule is ionized through the absorption of electromagnetic radiation, specifically photons, leading to the ejection of an electron. This section focuses on single-photon and multiphoton variants, where the photon energy or combined energies exceed the ionization energy (IE). These processes are fundamental in fields ranging from atomic physics to atmospheric chemistry, enabling selective ionization without significant thermal effects. Single-photon ionization occurs when a single photon with energy IE is absorbed, promoting an electron from a bound orbital to the continuum. The probability of this process is quantified by the photoionization cross section , derived from quantum mechanical time-dependent perturbation theory, which is proportional to the square of the dipole matrix element between the initial bound state and the final continuum state: , where and are the initial and final wave functions, is the position operator, and is the photon polarization vector.[36] In practice, for atoms, the cross section decreases as above threshold due to the radial wave function overlap. A key application is in atmospheric science, where solar ultraviolet radiation (wavelengths ~80–100 nm) ionizes O₂ molecules in the ionosphere, producing O₂⁺ ions essential for plasma formation and radio wave propagation; measured cross sections peak near 18 eV with values around 10⁻¹⁷ cm². Multiphoton ionization (MPI) extends this to scenarios where laser intensities are moderate (10⁹–10¹² W/cm²), allowing absorption of photons such that IE, even if individual photon energies are below threshold. In the perturbative regime, the ionization rate follows , where is the laser intensity and is the generalized -photon cross section, with units adjusted by for dimensionality.[37] This process was pioneered in the 1960s using early ruby lasers (emitting at 694 nm), enabling the first observations of two-photon ionization in alkali vapors like cesium.[38] Thresholds in MPI exhibit sharp onsets, but resonances—such as intermediate excited states—enhance rates via resonance-enhanced MPI (REMPI), improving selectivity. Above-threshold ionization (ATI), a related phenomenon, involves absorption of additional photons beyond the minimum , imparting excess kinetic energy to the electron; the spectrum shows peaks separated by , shifted by the ponderomotive energy , where is the field amplitude, the electron mass, and the angular frequency—representing the cycle-averaged quiver energy of a free electron. ATI was first observed in 1979 using noble gases under intense laser fields.[39] Experimental setups for photoionization often employ laser-based photoionization mass spectrometry (PIMS), which combines tunable lasers with time-of-flight mass analyzers to detect ionized species selectively by their ionization potentials. Development accelerated in the 1960s with ruby lasers, evolving into versatile tools for trace gas analysis by the 1970s.[40] For molecules, photoionization dynamics are complicated by autoionizing states—superexcited levels above IE that decay spontaneously into ion + electron continua—and shape resonances, where the outgoing electron temporarily traps in a centrifugal or molecular potential barrier, manifesting as broad enhancements in cross sections (e.g., π* shape resonance in N₂ at ~15 eV). These features lead to Fano-like asymmetric profiles in spectra, influencing branching ratios and angular distributions.[41]Field-Induced Processes

Field-induced ionization refers to the process where strong electric fields distort the atomic or molecular potential barriers, enabling electron escape through quantum tunneling or barrier suppression. This mechanism is distinct from thermal or photonic excitation, as it relies primarily on the field's influence on the potential energy landscape. In static fields, typically direct current (DC) or low-frequency alternating current (AC) fields, electrons tunnel through a triangular barrier formed by the superposition of the atomic Coulomb potential and the external field. The foundational theory for this static field emission, known as cold emission due to its temperature independence, was developed in 1928 by Ralph H. Fowler and Lothar Nordheim, who derived an expression for the emission current density based on the WKB approximation for tunneling probability.[42] The Fowler-Nordheim equation quantifies the current density for electron emission from a metal surface in a static electric field , approximated as: where is the electron charge, is Planck's constant, is the electron mass, and is the work function of the material. This exponential dependence highlights the field's critical role in reducing the barrier width, allowing observable currents at field strengths on the order of 1-10 GV/m for typical metals. Applications of static field ionization include field emission microscopy, where sharp tips emit electrons to image atomic-scale surface structures with high resolution, and ion sources for particle accelerators, such as liquid metal ion sources that generate focused beams via field evaporation of surface atoms.[42][43][44] In dynamic fields, such as those from oscillating AC or laser pulses, the time-varying nature leads to barrier suppression rather than pure tunneling, particularly at high intensities. The Keldysh parameter , where is the field oscillation frequency, is the ionization potential, and other symbols as before, delineates the regimes: perturbative multiphoton ionization dominates when (high frequency, low intensity), while non-perturbative tunneling or barrier suppression prevails for (low frequency, high intensity). This parameter, introduced in Leonid Keldysh's 1965 theory, provides a framework for understanding field-driven ionization across optical to infrared wavelengths. In plasma contexts, field-induced processes contribute to avalanche ionization in dielectrics, where initial seed electrons gain energy from the field and collide to ionize additional atoms, leading to rapid electron density growth and breakdown. This mechanism is prominent in laser-matter interactions within transparent materials, where the field strength exceeds the material's bandgap, initiating a cascade that can damage optics or enable plasma formation. For instance, in femtosecond laser pulses, field-dependent avalanche rates determine the damage threshold, with critical fields around 0.1-1 MV/cm for common dielectrics like fused silica.[45][46]Theoretical Descriptions

Semi-Classical Approaches

Semi-classical approaches to ionization integrate classical descriptions of electron trajectories with quantum mechanical elements to model the escape of electrons from atomic or molecular potentials under external fields. In these models, the electron's motion is treated classically once it is sufficiently far from the nucleus or ion core, influenced by the combined Coulomb and external field potentials, while quantum transitions or initial conditions account for the departure from bound states. This hybrid framework is especially effective for Rydberg states, where the large orbital radii allow classical-like behavior, enabling the study of field-induced escape dynamics without full quantum wavefunction computations. A central model within this paradigm is the classical over-the-barrier ionization (OBI) framework, where ionization occurs when the external field suppresses the Coulomb barrier below the electron's energy level, permitting classical escape over the saddle point of the potential. This model incorporates Coulomb focusing, in which the attractive field of the residual ion core bends and converges the trajectories of outgoing electrons, modifying their asymptotic momentum distributions and enhancing recollision probabilities in intense laser fields. Developed as an extension of earlier classical trajectory methods, the OBI approach provides intuitive insights into barrier penetration without relying on tunneling probabilities.[47][48] These semi-classical techniques find key applications in interpreting high-order above-threshold ionization (ATI) spectra, where classical electron trajectories driven by laser fields explain the characteristic energy plateaus, cutoffs, and angular distributions observed in photoelectron experiments. By simulating ensembles of trajectories launched from quantum-initialized states, the models capture rescattering effects that contribute to the multi-photon absorption features beyond the ponderomotive limit. Additionally, they elucidate the role of classical chaos in atomic systems, particularly for Rydberg atoms in microwave or static fields, where irregular, diffusive trajectories lead to broadband ionization thresholds and sensitivity to field perturbations.[49][50] Despite their strengths, semi-classical approaches have limitations, particularly at low electron energies where quantum tunneling through the barrier dominates, rendering classical escape improbable and necessitating full quantum treatments. Originating in the 1970s through advancements in atomic collision theory, these methods evolved from semiclassical impact-parameter approximations to address electron promotion and capture, providing a foundation for later strong-field extensions.[51][52]Quantum Mechanical Models

Quantum mechanical models of ionization fundamentally rely on solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation (TDSE) for an atomic system interacting with an external field, treating the field as a perturbation to the unperturbed atomic Hamiltonian. These approaches capture the quantum nature of electron dynamics, including wavefunction evolution and transition probabilities, contrasting with semi-classical methods by emphasizing full operator-based descriptions rather than hybrid trajectories. For weak fields, where the perturbation does not significantly distort the bound states, time-independent perturbation theory provides corrections to energy levels, while time-dependent formulations yield transition rates to continuum states representing ionization.[53] The foundational framework for time-dependent perturbation theory was established by Dirac in 1926, enabling the calculation of transition amplitudes between initial bound states and final continuum states under weak, time-varying perturbations such as electromagnetic fields.[53] In the limit of a continuum of final states, this leads to Fermi's golden rule, which gives the transition rate from an initial state to final states as where is the perturbation Hamiltonian (e.g., the dipole interaction for an electric field ) and is the density of final states at energy matching the initial energy plus absorbed photon energy. This rate quantifies photoionization probabilities in weak laser fields, assuming first-order processes where the electron is promoted directly to the continuum. For static weak fields, time-independent perturbation theory similarly shifts bound-state energies, revealing avoided crossings that signal potential ionization pathways, though exact continuum transitions require the time-dependent extension. For the simplest atomic system, the hydrogen atom, exact solutions to the Schrödinger equation exist in specific field configurations, providing benchmarks for ionization models. In a uniform static electric field, the Hamiltonian separates exactly in parabolic coordinates , where and , yielding separable wavefunctions and energy levels labeled by quantum numbers , , (with ). This Stark effect solution shows linear energy shifts for low-lying states and quadratic for higher ones, with the field-induced mixing of states lowering the ionization threshold and enabling tunneling-like escape in stronger fields, though perturbative limits suffice for weak perturbations. These exact hydrogenic results, first derived using parabolic coordinates in the early quantum era, underpin approximations for more complex atoms by highlighting field-induced asymmetry in electron probability distributions. In time-dependent scenarios, such as laser pulses, advanced basis states account for field-dressing of electrons. Volkov states describe free electrons in a plane-wave laser field, providing exact solutions to the TDSE for a particle in a classical electromagnetic wave, with the wavefunction incorporating oscillatory momentum shifts due to the vector potential . These states are used to construct "dressed" continuum wavefunctions in ionization amplitudes, capturing the quiver motion of ionized electrons without atomic binding. For monochromatic or periodic fields, Floquet theory transforms the TDSE into a time-independent eigenvalue problem via quasienergy states, where solutions take the form with periodic in the field cycle , . This approach reveals Floquet sidebands in the energy spectrum, corresponding to multi-photon ionization channels, and is particularly useful for high-frequency fields where perturbation theory breaks down but periodicity persists. In the perturbative regime, Floquet methods recover Dirac's results, while non-perturbatively they predict dynamical stabilization against ionization. For multi-electron atoms, where electron correlation complicates single-particle pictures, configuration interaction (CI) approximations expand the many-body wavefunction as a linear combination of Slater determinants from a basis of orbitals, solving the TDSE or TISE variationally to include interactions beyond mean-field Hartree-Fock. Seminal applications, such as Hylleraas' early CI for helium ground-state energy, demonstrate how mixing configurations (e.g., promoting an electron to a continuum orbital) captures correlation effects in ionization potentials and rates. Truncated CI, like singles-doubles (CISD), balances accuracy and computation for systems like neon or alkali atoms, yielding ionization energies within 0.1 eV of experiment by accounting for double excitations that mimic shake-up during ejection. These methods extend hydrogenic models by incorporating effective potentials, providing a quantum foundation for understanding correlated multi-electron escape in weak fields. Such full-wavefunction approaches serve as limits for semi-classical approximations in more intense regimes.Strong Field Approximations

The strong-field approximation (SFA) provides a non-perturbative framework for describing ionization processes in intense laser fields, where the interaction is dominated by the external field rather than atomic potentials. In this approach, the transition from a bound initial state to a continuum final state is computed using the S-matrix element, which neglects the Coulomb interaction after ionization and treats the electron as propagating in the laser field alone. The ionization rate is then obtained as , where is the pulse duration, the sum is over final states, and arises from the time evolution operator in the interaction picture. The SFA amplitudes are evaluated using the saddle-point method applied to the classical action , where is the canonical momentum, is the vector potential of the laser field, and is the electron mass. This integral yields saddle points that determine the dominant contributions to the transition amplitude, resulting in an ionization rate approximated by , capturing the exponential suppression due to tunneling or multiphoton processes.[54] The approximation is valid in the regime of high laser intensities where the ponderomotive energy (with the field amplitude and the frequency) greatly exceeds the ionization energy , ensuring that the field dressing of the continuum states dominates over atomic binding. Extensions of the SFA distinguish between velocity-gauge and length-gauge formulations; the velocity gauge, which uses the vector potential directly, is typically preferred for its numerical stability and accuracy in describing electron trajectories, while the length gauge, based on the electric field, can introduce gauge-dependent artifacts at low frequencies.[55] Historically, the SFA traces to the 1965 work of Keldysh, who introduced the foundational non-perturbative treatment for multiphoton and tunneling ionization, with key developments in the 1980s by Reiss formalizing the S-matrix approach for intense fields.[56]Advanced Phenomena

Tunnel Ionization Dynamics

Tunnel ionization occurs when an electron in an atom or molecule escapes through an exponentially suppressed potential barrier induced by a strong electric field, rather than surmounting it classically. This quantum mechanical process was first theoretically described for static fields in the context of field emission from atoms. In such scenarios, the barrier is distorted by the field, allowing the electron wavefunction to penetrate and emerge on the other side with a probability that decays exponentially with the barrier width. For alternating electromagnetic fields, particularly those from intense lasers, the Ammosov-Delone-Krainov (ADK) model provides a widely used expression for the tunneling ionization rate of complex atoms and ions from arbitrary initial states. The ADK rate is given by where is the field strength, is the charge of the residual ion, is the effective principal quantum number with the ionization potential, is the absolute value of the magnetic quantum number, and is a coefficient related to the initial orbital.[57] This model builds on the strong field approximation, adapting static tunneling concepts to time-varying fields.[58] In the quasi-static approximation, valid for low-frequency fields where , the ionization rate is treated as instantaneous and depends on the field's phase at the moment of tunneling, effectively averaging the static rate over the field's cycle.[59] For higher frequencies, dynamic tunneling effects become prominent, involving imaginary-time trajectories in the electron's path under the oscillating field; here, the Keldysh parameter quantifies the transition from tunneling () to multiphoton regimes, with modifications to the barrier penetration accounting for the field's temporal variation.[60] Key observables in tunnel ionization dynamics include ionization delay times, which measure the temporal offset between peak field strength and electron release—often on the attosecond scale—and transverse momentum distributions of ionized electrons, revealing the tunneling exit geometry and field-induced acceleration.[61] These have been probed experimentally using attoclock techniques and streaking methods.[62] Historically, while Oppenheimer's 1928 work laid the static foundation, adaptations for laser fields emerged in the 1990s with the advent of tabletop intense laser systems, enabling studies of AC tunneling in gases and solids.[63]Multiple Ionization Effects

Multiple ionization refers to the removal of more than one electron from an atom or molecule under intense laser fields, often revealing correlated electron dynamics beyond independent single-electron processes. In strong-field regimes, such as those accessed by Ti:sapphire lasers in the 1990s, experiments on noble gases like argon and xenon demonstrated enhanced double ionization yields at specific intensities, signaling non-sequential mechanisms. Non-sequential double ionization (NSDI) occurs when an initially tunnel-ionized electron recollides with the parent ion, ejecting a second electron through electron-impact ionization. This recollision model, proposed in the early 1990s, explains the characteristic "knee" in the double-ionization yield versus laser intensity curve, where the yield rises more steeply than predicted by sequential ionization at intensities around 10^14–10^15 W/cm² for noble gases.[64] Early observations in the mid-1990s using femtosecond Ti:sapphire lasers confirmed this knee structure in argon, attributing it to correlated electron ejection driven by the recolliding electron's kinetic energy peaking at about 3.17 U_p, where U_p is the ponderomotive energy. Population trapping arises in alternating current (AC) fields when electrons are localized in stable Rydberg-like states, librating without ionizing due to AC Stark shifts that detune multiphoton resonances. This effect stabilizes population in high-lying states by shifting their energies such that the field-dressed levels avoid further ionization pathways, observed in xenon atoms under femtosecond Ti:sapphire pulses where trapping efficiency depends on the laser frequency and intensity matching the Stark-shifted resonance conditions. In noble gases, trapping manifests as reduced ionization rates at specific field parameters, contrasting with over-the-barrier escape in unbound trajectories.[65] For molecules, inner-valence multiphoton ionization (MPI) excites electrons from deeper orbitals, often leading to unstable dications and rapid dissociation. In nitrogen (N₂), inner-valence ionization populates repulsive states of the N₂²⁺ dication, resulting in N⁺ + N⁺ fragmentation with kinetic energy releases around 5–10 eV, as probed by wavelength-selected XUV pulses.[66] This process highlights site-specific dynamics, where inner-shell excitation destabilizes the molecular bond more effectively than outer-valence removal, contributing to observed dissociation times on the femtosecond scale.[67] Correlated effects in molecules are exemplified by charge-resonance enhanced ionization (CREI), where the potential energy curves of ionic states cross at a critical internuclear distance (typically 2–3 a₀ for diatomic systems), enabling resonant coupling that boosts the second ionization rate. In CO₂ and H₂⁺, CREI amplifies multiple ionization as the molecule stretches during the laser pulse, with enhancement factors up to orders of magnitude over atomic rates at internuclear separations matching the laser photon energy.[68] These correlations were first theoretically detailed in the mid-1990s and later observed in experiments with intense infrared pulses, underscoring the role of nuclear motion in multi-electron ejection.[69]Kramers-Henneberger Transformations

The Kramers-Henneberger transformation is a unitary transformation used to analyze the dynamics of atoms exposed to intense, oscillating laser fields by shifting to a non-inertial reference frame that tracks the classical quiver motion of the electron induced by the field. This approach, originally developed by W. Henneberger in 1968 as a perturbation method for atoms in intense monochromatic radiation, builds on earlier ideas from H. A. Kramers in the 1950s regarding accelerated frames in quantum mechanics. In the 1960s, extensions of this framework were applied to quantum optics, facilitating the study of field-dressed states in periodic potentials.[70] The transformation effectively dresses the atomic potential with the laser field, providing insight into how intense fields modify electronic structure without direct inclusion of the vector potential in the Hamiltonian. In the Kramers-Henneberger frame, the coordinate transformation follows the quiver displacement , defined as , where is the vector potential of the laser field and is the speed of light (in atomic units, this simplifies accordingly). This shift to an accelerated frame incorporates the laser's oscillatory drive into the atomic potential, yielding a time-dependent effective potential . For high-frequency fields where the laser period is much shorter than atomic response times, a cycle-averaged, quasi-static effective potential emerges: with the optical period. This averaged potential captures the ponderomotive effects and field-induced modifications to binding, such as stabilization or destabilization of states.[71] The transformation finds key applications in describing quiver-averaged potentials for atoms and molecules in high-frequency regimes, where the electron's oscillatory motion smears the Coulomb interaction, leading to altered energy levels and ionization thresholds. In molecular systems, it predicts phenomena like bond softening, where the effective potential reduces internuclear barriers and lowers dissociation energies, or bond hardening under certain field polarizations that enhance stability. These predictions arise from the displacement of charge distributions in the laser-dressed frame, offering a length-gauge perspective complementary to velocity-gauge formulations in strong-field approximations (SFA), which simplify multiphoton and tunneling ionization rates.[71] Despite its utility, the Kramers-Henneberger transformation has limitations, particularly breaking down for low-frequency fields where the quiver period approaches atomic timescales, preventing valid cycle averaging and leading to non-adiabatic effects. It also falters under strong Coulomb interactions, as the assumption of nearly free-electron quiver motion fails when binding energies compete with the field-driven oscillations.[72] These constraints highlight its suitability primarily for the high-frequency approximation in intense-field physics.Applications and Distinctions

Practical Uses