Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geography and cartography in the medieval Islamic world

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Geography |

|---|

|

| History of geography |

|---|

|

|

|

Medieval Islamic geography and cartography refer to the study of geography and cartography in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age (variously dated between the 8th century and 16th century). Muslim scholars made advances to the map-making traditions of earlier cultures,[1] explorers and merchants learned in their travels across the Old World (Afro-Eurasia).[1] Islamic geography had three major fields: exploration and navigation, physical geography, and cartography and mathematical geography.[1] Islamic geography reached its apex with Muhammad al-Idrisi in the 12th century.

History

[edit]8th and 9th century

[edit]Islamic geography began in the 8th century, influenced by Hellenistic geography,[2] combined with what explorers and merchants learned in their travels across the Old World (Afro-Eurasia).[1] Muslim scholars engaged in extensive exploration and navigation during the 9th-12th centuries, including journeys across the Muslim world, in addition to regions such as China, Southeast Asia and Southern Africa.[1] Various Islamic scholars contributed to the development of geography and cartography, with the most notable including Al-Khwārizmī, Abū Zayd al-Balkhī (founder of the "Balkhi school"), Al-Masudi, Abu Rayhan Biruni and Muhammad al-Idrisi.

Islamic geography was patronized by the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad. An important influence in the development of cartography was the patronage of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun, who reigned from 813 to 833. He commissioned several geographers to perform an arc measurement, determining the distance on Earth that corresponds to one degree of latitude along a meridian (al-Ma'mun's arc measurement). Thus his patronage resulted in the refinement of the definition of the Arabic mile (mīl in Arabic) in comparison to the stadion used in the Hellenistic world. These efforts also enabled Muslims to calculate the circumference of the Earth. Al-Mamun also commanded the production of a large map of the world, which has not survived,[3]: 61–63 though it is known that its map projection type was based on Marinus of Tyre rather than Ptolemy.[4]: 193

Islamic cartographers inherited Ptolemy's Almagest and Geography in the 9th century. These works stimulated an interest in geography (particularly gazetteers) but were not slavishly followed.[5] Instead, Arabian and Persian cartography followed Al-Khwārizmī in adopting a rectangular projection, shifting Ptolemy's Prime Meridian several degrees eastward, and modifying many of Ptolemy's geographical coordinates.

Having received Greek writings directly and without Latin intermediation, Arabian and Persian geographers made no use of T-O maps.[5]

In the 9th century, the Persian mathematician and geographer, Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi, employed spherical trigonometry and map projection methods in order to convert polar coordinates to a different coordinate system centred on a specific point on the sphere, in this the Qibla, the direction to Mecca.[6] Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī (973–1048) later developed ideas which are seen as an anticipation of the polar coordinate system.[7] Around 1025, he describes a polar equi-azimuthal equidistant projection of the celestial sphere.[8]: 153 However, this type of projection had been used in ancient Egyptian star-maps and was not to be fully developed until the 15 and 16th centuries.[9]

Khordadbeh–Jayhani tradition

[edit]The works of Ibn Khordadbeh (c. 870) and Jayhani (c. 910s) were at the basis of a new Perso-Arab tradition in Persia and Central Asia.[10] The exact relationship between the books of Khordadbeh and Jayhani is unknown, because the two books had the same title, have often been mixed up, and Jayhani's book has been lost, so that it can only be approximately reconstructed from the works of other authors (mostly from the eastern parts of the Islamic world[11]) who seem to have reused some of its contents.[10][12] According to Vasily Bartold, Jayhani based his book primarily on the data he had collected himself, but also reused Khordadbeh's work to a considerable extent.[10] Unlike the Balkhi school, geographers of the Khordadbeh–Jayhani tradition sought to describe the whole world as they knew it, including the lands, societies and cultures of non-Muslims.[13] As vizier of the Samanid Empire, Jayhani's diplomatic correspondence allowed him to collect much valuable information from people in faraway lands.[14] Nevertheless, Al-Masudi criticised Jayhani for overemphasising geological features of landscapes, stars and geometry, taxation systems, trade roads and stations allegedly few people used, while ignoring major population centres, provinces and military roads and forces.[15]

Balkhi school

[edit]The Balkhī school of terrestrial mapping, originated by Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (from Balkh) in early 10th century Baghdad, and significantly developed by Istakhri,[11] had a conservative and religious character: it was only interested in describing mamlakat al-Islām ("Islamic lands"), which the school divided into 20 or more iqlīms ("climes" or provinces).[13] Balkhi and his followers reoriented geographic knowledge in order to bring it in line with certain concepts found in the Quran, emphasised the central importance of Mecca and Arabia, and ignored the non-Islamic world.[13] This distinguished them from earlier geographers such as Ibn Khordadbeh and Al-Masudi, who described the whole world as they knew it.[13] The geographers of this school, such as Istakhri, al-Muqaddasi and Ibn Hawqal, wrote extensively of the peoples, products, and customs of areas in the Muslim world, with little interest in the non-Muslim realms,[3] and produced world atlases, each one featuring a world map and twenty regional maps.[4]: 194

Regional cartography

[edit]

Islamic regional cartography is usually categorized into three groups: that produced by the "Balkhī school", the type devised by Muhammad al-Idrisi, and the type that are uniquely found in the Book of curiosities.[3]

The maps by the Balkhī schools were defined by political, not longitudinal boundaries and covered only the Muslim world. In these maps the distances between various "stops" (cities or rivers) were equalized. The only shapes used in designs were verticals, horizontals, 90-degree angles, and arcs of circles; unnecessary geographical details were eliminated. This approach is similar to that used in subway maps, most notable used in the "London Underground Tube Map" in 1931 by Harry Beck.[3]: 85–87

Al-Idrīsī defined his maps differently. He considered the extent of the known world to be 160° and had to symbolize 50 dogs in longitude and divided the region into ten parts, each 16° wide. In terms of latitude, he portioned the known world into seven 'climes', determined by the length of the longest day. In his maps, many dominant geographical features can be found.[3]

Book on the appearance of the Earth

[edit]Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī's Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ ("Book on the appearance of the Earth") was completed in 833. It is a revised and completed version of Ptolemy's Geography, consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates of cities and other geographical features following a general introduction.[16]

Al-Khwārizmī, Al-Ma'mun's most famous geographer, corrected Ptolemy's gross overestimate for the length of the Mediterranean Sea[4]: 188 (from the Canary Islands to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean); Ptolemy overestimated it at 63 degrees of longitude, while al-Khwarizmi almost correctly estimated it at nearly 50 degrees of longitude. Al-Ma'mun's geographers "also depicted the Atlantic and Indian Oceans as open bodies of water, not land-locked seas as Ptolemy had done. "[17] Al-Khwarizmi thus set the Prime Meridian of the Old World at the eastern shore of the Mediterranean, 10–13 degrees to the east of Alexandria (the prime meridian previously set by Ptolemy) and 70 degrees to the west of Baghdad. Most medieval Muslim geographers continued to use al-Khwarizmi's prime meridian.[4]: 188 Other prime meridians used were set by Abū Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdānī and Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi at Ujjain, a centre of Indian astronomy, and by another anonymous writer at Basra.[4]: 189

Al-Biruni

[edit]

Abu Rayhan al-Biruni (973–1048) devised a novel method of determining the Earth's radius by means of the observation of the height of a mountain. He carried it out at Nandana in Pind Dadan Khan (present-day Pakistan).[18] He used trigonometry to calculate the radius of the Earth using measurements of the height of a hill and measurement of the dip in the horizon from the top of that hill. His calculated radius for the Earth of 3928.77 miles was 2% higher than the actual mean radius of 3847.80 miles.[19] His estimate was given as 12,803,337 cubits, so the accuracy of his estimate compared to the modern value depends on what conversion is used for cubits. The exact length of a cubit is not clear; with an 18-inch cubit his estimate would be 3,600 miles, whereas with a 22-inch cubit his estimate would be 4,200 miles.[20] One significant problem with this approach is that Al-Biruni was not aware of atmospheric refraction and made no allowance for it. He used a dip angle of 34 arc minutes in his calculations, but refraction can typically alter the measured dip angle by about 1/6, making his calculation only accurate to within about 20% of the true value.[21]

In his Codex Masudicus (1037), Al-Biruni theorized the existence of a landmass along the vast ocean between Asia and Europe, or what is today known as the Americas. He argued for its existence on the basis of his accurate estimations of the Earth's circumference and Afro-Eurasia's size, which he found spanned only two-fifths of the Earth's circumference, reasoning that the geological processes that gave rise to Eurasia must surely have given rise to lands in the vast ocean between Asia and Europe. He also theorized that at least some of the unknown landmass would lie within the known latitudes which humans could inhabit, and therefore would be inhabited.[22]

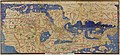

Tabula Rogeriana

[edit]The Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi produced his medieval atlas, Tabula Rogeriana or The Recreation for Him Who Wishes to Travel Through the Countries, in 1154. He incorporated the knowledge of Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Far East gathered by Arab merchants and explorers with the information inherited from the classical geographers to create the most accurate map of the world in pre-modern times.[23] With funding from Roger II of Sicily (1097–1154), al-Idrisi drew on the knowledge collected at the University of Córdoba and paid draftsmen to make journeys and map their routes. The book describes the Earth as a sphere with a circumference of 22,900 miles (36,900 km) but maps it in 70 rectangular sections. Notable features include the correct dual sources of the Nile, the coast of Ghana and mentions of Norway. Climate zones were a chief organizational principle. A second and shortened copy from 1192 called Garden of Joys is known by scholars as the Little Idrisi.[24]

On the work of al-Idrisi, S. P. Scott commented:[23]

The compilation of Edrisi marks an era in the history of science. Not only is its historical information most interesting and valuable, but its descriptions of many parts of the earth are still authoritative. For three centuries geographers copied his maps without alteration. The relative position of the lakes which form the Nile, as delineated in his work, does not differ greatly from that established by Baker and Stanley more than seven hundred years afterwards, and their number is the same. The mechanical genius of the author was not inferior to his erudition. The celestial and terrestrial planisphere of silver which he constructed for his royal patron was nearly six feet in diameter, and weighed four hundred and fifty pounds; upon the one side the zodiac and the constellations, upon the other—divided for convenience into segments—the bodies of land and water, with the respective situations of the various countries, were engraved.

— S. P. Scott, History of the Moorish Empire in Europe

Al-Idrisi's atlas, originally called the Nuzhat in Arabic, served as a major tool for Italian, Dutch and French mapmakers from the 16th century to the 18th century.[25]

Piri Reis map

[edit]The Piri Reis map is a world map compiled in 1513 by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis. Approximately one third of the map survives; it shows the western coasts of Europe and North Africa and the coast of Brazil with reasonable accuracy. Various Atlantic islands, including the Azores and Canary Islands, are depicted, as is the mythical island of Antillia and possibly Japan.

Others

[edit]Suhrāb, a late 10th-century Muslim geographer, accompanied a book of geographical coordinates with instructions for making a rectangular world map, with equirectangular projection or cylindrical equidistant projection.[3] The earliest surviving rectangular coordinate map is dated to the 13th century and is attributed to Hamdallah al-Mustaqfi al-Qazwini, who based it on the work of Suhrāb. The orthogonal parallel lines were separated by one degree intervals, and the map was limited to Southwest Asia and Central Asia. The earliest surviving world maps based on a rectangular coordinate grid are attributed to al-Mustawfi in the 14th or 15th century (who used invervals of ten degrees for the lines), and to Hafiz-i Abru (died 1430).[4]: 200–01

In the 11th century, the Karakhanid Turkic scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari was the first to draw a unique Islamic world map,[26] where he illuminated the cities and places of the Turkic peoples of Central and Inner Asia. He showed the lake Issyk-Kul (in nowadays Kyrgyzstan) as the centre of the world.

Ibn Battuta (1304–1368?) wrote "Rihlah" (Travels) based on three decades of journeys, covering more than 120,000 km through northern Africa, southern Europe, and much of Asia.

Muslim astronomers and geographers were aware of magnetic declination by the 15th century, when the Egyptian astronomer 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Wafa'i (d. 1469/1471) measured it as 7 degrees from Cairo.[27]

Instruments

[edit]

Muslim scholars invented and refined a number of scientific instruments in mathematical geography and cartography. These included the astrolabe, quadrant, gnomon, celestial sphere, sundial, and compass.[1]

Astrolabe

[edit]Astrolabes were adopted and further developed in the medieval Islamic world, where Muslim astronomers introduced angular scales to the design,[28] adding circles indicating azimuths on the horizon.[29] It was widely used throughout the Muslim world, chiefly as an aid to navigation and as a way of finding the Qibla, the direction of Mecca. Eighth-century mathematician Muhammad al-Fazari is the first person credited with building the astrolabe in the Islamic world.[30]

The mathematical background was established by Muslim astronomer Albatenius in his treatise Kitab az-Zij (c. 920 AD), which was translated into Latin by Plato Tiburtinus (De Motu Stellarum). The earliest surviving astrolabe is dated AH 315 (927–28 AD). In the Islamic world, astrolabes were used to find the times of sunrise and the rising of fixed stars, to help schedule morning prayers (salat). In the 10th century, al-Sufi first described over 1,000 different uses of an astrolabe, in areas as diverse as astronomy, astrology, navigation, surveying, timekeeping, prayer, Salat, Qibla, etc.[31][32]

Compass

[edit]

The earliest reference to a compass in the Muslim world occurs in a Persian talebook from 1232,[34][35] where a compass is used for navigation during a trip in the Red Sea or the Persian Gulf.[36] The fish-shaped iron leaf described indicates that this early Chinese design has spread outside of China.[37] The earliest Arabic reference to a compass, in the form of magnetic needle in a bowl of water, comes from a work by Baylak al-Qibjāqī, written in 1282 while in Cairo.[34][38] Al-Qibjāqī described a needle-and-bowl compass used for navigation on a voyage he took from Syria to Alexandria in 1242.[34] Since the author describes having witnessed the use of a compass on a ship trip some forty years earlier, some scholars are inclined to antedate its first appearance in the Arab world accordingly.[34] Al-Qibjāqī also reports that sailors in the Indian Ocean used iron fish instead of needles.[39]

Late in the 13th century, the Yemeni Sultan and astronomer al-Malik al-Ashraf described the use of the compass as a "Qibla indicator" to find the direction to Mecca.[40] In a treatise about astrolabes and sundials, al-Ashraf includes several paragraphs on the construction of a compass bowl (ṭāsa). He then uses the compass to determine the north point, the meridian (khaṭṭ niṣf al-nahār), and the Qibla. This is the first mention of a compass in a medieval Islamic scientific text and its earliest known use as a Qibla indicator, although al-Ashraf did not claim to be the first to use it for this purpose.[33][41]

In 1300, an Arabic treatise written by the Egyptian astronomer and muezzin Ibn Simʿūn describes a dry compass used for determining qibla. Like Peregrinus' compass, however, Ibn Simʿūn's compass did not feature a compass card.[33] In the 14th century, the Syrian astronomer and timekeeper Ibn al-Shatir (1304–1375) invented a timekeeping device incorporating both a universal sundial and a magnetic compass. He invented it for the purpose of finding the times of prayers.[42] Arab navigators also introduced the 32-point compass rose during this time.[43] In 1399, an Egyptian reports two different kinds of magnetic compass. One instrument is a "fish" made of willow wood or pumpkin, into which a magnetic needle is inserted and sealed with tar or wax to prevent the penetration of water. The other instrument is a dry compass.[39]

In the 15th century, the description given by Ibn Majid while aligning the compass with the pole star indicates that he was aware of magnetic declination. An explicit value for the declination is given by ʿIzz al-Dīn al-Wafāʾī (fl. 1450s in Cairo).[36]

Premodern Arabic sources refer to the compass using the term ṭāsa (lit. "bowl") for the floating compass, or ālat al-qiblah ("qibla instrument") for a device used for orienting towards Mecca.[36]

Friedrich Hirth suggested that Arab and Persian traders, who learned about the polarity of the magnetic needle from the Chinese, applied the compass for navigation before the Chinese did.[44] However, Needham described this theory as "erroneous" and "it originates because of a mistranslation" of the term chia-ling found in Zhu Yu's book Pingchow Table Talks.[45]

Notable geographers

[edit]Khordadbeh–Jayhani tradition geographers

[edit]- Ibn Khordadbeh (820–912): Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik ("Book of Roads and Kingdoms")[10]

- Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Jayhani (died 925): Kitāb al-Masālik wal-Mamālik ("Book of Roads and Kingdoms", lost)[10]

- Ahmad ibn Rustah (10th century)[14]

- Al-Masudi (896–956):[10][46] The Meadows of Gold[46]

- Al-Bakri (c. 1040–1094)[14]

- Gardizi (died 1061)[14]

- Muhammad Aufi[14]

Balkhi school geographers

[edit]- Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (850–934): Suwar al-aqālīm ("Images of the Climes")[11] or al-Amthila wa-suwar al-ard ("Similitudes and Images of the Earth"), written in 920 or after[11]

- Istakhri (died mid-10th century): al-Masālik wal-Mamālik ("Roads and Kingdoms").[47][48]

- Ibn Hawqal (died after 978):[13][49] Kitāb Sūrat al-ard[13] ("Book of the Face of the Earth")

- Al-Maqdisi (c. 945/946–991):[13][49] Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fi maʾarfat al-aqalīm[13] ("The Finest Divisions Concerning Knowledge of the Climes")[13]

- Abu al-Fida (Abulfeda, 1273–1331):[13] Taqwīm al-Buldān ("Correct Account of the Lands")[13]

- (probably) Hafiz-i Abru (died 1430)[13]

- Istakhri (died mid-10th century): al-Masālik wal-Mamālik ("Roads and Kingdoms").[47][48]

Others

[edit]- Al-Kindi (Alkindus, 801–873)

- Ya'qubi (died 897)

- Al-Dinawari (820–898)

- Hamdani (893–945)

- Ibn al-Faqih (10th century)

- Ahmad ibn Fadlan (10th century)

- Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965–1039)

- Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī (973–1048)

- Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037)

- Muhammad al-Idrisi (Dreses, 1100–1165)

- Ibn Jubayr (1145–1217)

- Yaqut al-Hamawi (1179–1229)

- Hamdollah Mostowfi (1281–1349)

- Ibn al-Wardi (d. 1457)

- Ibn Battuta (1304–1370s)

- Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406)

- Ahmad Bin Majid (born 1432)

- Mahmud al-Kashgari (1005–1102)

- Piri Reis (1465–1554)

- Amin Razi (16th century)

Gallery

[edit]-

Al-Masudi's world map (10th century)

-

Schematic map of Sicily in the Arabic Book of Curiosities

-

10th century map of the World by Ibn Hawqal.

-

The Persian Gulf in a regional map of the Atlas of Islam

-

Map from Mahmud al-Kashgari's Diwan (11th century)

-

Ibn al-Wardi's atlas of the world (~1450), a manuscript copied in the 17th century

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Buang, Amriah (2014). "Geography in the Islamic World". Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-3934-5_8611-2. ISBN 978-94-007-3934-5.

A prominent feature of the achievement of Muslim scholars in mathematical geography and cartography was the invention of scientific instruments of measurement. Among these were the astrolab (astrolabe), the ruba (quadrant), the gnomon, the celestial sphere, the sundial, and the compass.

- ^ Gerald R. Tibbetts, The Beginnings of a Cartographic Tradition, in: John Brian Harley, David Woodward: Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies, Chicago, 1992, pp. 90–107 (97-100), ISBN 0-226-31635-1

- ^ a b c d e f Edson and Savage-Smith (2004)[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy, Edward S. (1996). "Mathematical Geography". In Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis (eds.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 3. Routledge. pp. 185–201. ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2.

- ^ a b Edson & Savage-Smith 2004, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Koetsier, T.; Bergmans, L. (2005). Mathematics and the Divine. Elsevier. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-444-50328-2.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Arrayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ King, David A. (1996). "Astronomy and Islamic society: Qibla, gnomics and timekeeping". In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 1. London, UK and New York, USA: Routledge. pp. 128–184.

- ^ Rankin, Bill (2006). "Projection Reference". Radical Cartography.

- ^ a b c d e f Bosworth & Asimov 2003, p. 217–218.

- ^ a b c d Bosworth & Asimov 2003, p. 218.

- ^ Minorsky 1937, p. xvi–xvii.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bosworth & Asimov 2003, p. 219.

- ^ a b c d e Minorsky 1937, p. xvii.

- ^ Minorsky 1937, p. xviii.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Cartography", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Covington, Richard (2007). "Nation, identity and the fascination with forensic science in Sherlock Holmes and CSI". Saudi Aramco World, May–June 2007. 10 (3): 17–21. doi:10.1177/1367877907080149. S2CID 145173935. Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ Pingree 2010b.

- ^ Sparavigna, Amelia (2013). "The Science of Al-Biruni". International Journal of Sciences. 2 (12): 52–60. arXiv:1312.7288. doi:10.18483/ijSci.364. S2CID 119230163.

- ^ Douglas (1973, p.211)

- ^ Huth, John Edward (2013). The Lost Art of Finding Our Way. Harvard University Press. pp. 216–217. ISBN 9780674072824.

- ^ Starr, S. Frederick (12 December 2013). "So, Who Did Discover America?". historytoday.com. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ a b Scott, S. P. (1904). History of the Moorish Empire in Europe. Harvard University Press. pp. 461–2.

- ^ "Slide #219: World Maps of al-Idrisi". Henry Davis Consulting. Archived from the original on 2006-06-26. Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- ^ Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven; Wallis, Faith (2014). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 261. ISBN 9781135459321.

- ^ Hermann A. Die älteste türkische Weltkarte (1076 η. Ch.) // Imago Mundi: Jahrbuch der Alten Kartographie. – Berlin, 1935. – Bd.l. – S. 21—28.

- ^ Barmore, Frank E. (April 1985), "Turkish Mosque Orientation and the Secular Variation of the Magnetic Declination", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 44 (2), University of Chicago Press: 81–98 [98], doi:10.1086/373112, S2CID 161732080

- ^ See p. 289 of Martin, L. C. (1923), "Surveying and navigational instruments from the historical standpoint", Transactions of the Optical Society, 24 (5): 289–303, Bibcode:1923TrOS...24..289M, doi:10.1088/1475-4878/24/5/302, ISSN 1475-4878.

- ^ Berggren, J. Lennart (2007), "Mathematics in Medieval Islam", in Katz, Victor J. (ed.), The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: a Sourcebook, Princeton University Press, p. 519, ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9

- ^ Richard Nelson Frye: Golden Age of Persia. p. 163

- ^ Dr. Emily Winterburn (National Maritime Museum), Using an Astrolabe, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation, 2005.

- ^ Lachièz-Rey, Marc; Luminet, Jean-Pierre (2001). Celestial Treasury: From the Music of Spheres to the Conquest of Space. Trans. Joe Laredo. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-521-80040-2.

- ^ a b c Schmidl, Petra G. (1996–97). "Two Early Arabic Sources on the Magnetic Compass". Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies. 1: 81–132. doi:10.5617/jais.4547. http://www.uib.no/jais/v001ht/01-081-132schmidl1.htm#_ftn4 Archived 2014-09-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Kreutz, Barbara M. (1973) "Mediterranean Contributions to the Medieval Mariner's Compass", Technology and Culture, 14 (3: July), p. 367–383 JSTOR 3102323

- ^ Jawāmeʿ al-ḥekāyāt wa-lawāmeʿ al-rewāyāt by Muhammad al-ʿAwfī

- ^ a b c Schmidl, Petra G. (2014-05-08). "Compass". In Ibrahim Kalin (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 144–6. ISBN 978-0-19-981257-8.

- ^ Needham p. 12-13 "...that the floating fish-shaped iron leaf spread outside China as a technique, we know from the description of Muhammad al' Awfi just two hundred years later"

- ^ Kitāb Kanz al-tujjār fī maʿrifat al-aḥjār

- ^ a b "Early Arabic Sources on the Magnetic Compass" (PDF). Lancaster.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ^ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1988). "Gleanings from an Arabist's Workshop: Current Trends in the Study of Medieval Islamic Science and Medicine". Isis. 79 (2): 246–266 [263]. doi:10.1086/354701. PMID 3049439. S2CID 33884974.

- ^ Schmidl, Petra G. (2007). "Ashraf: al-Malik al-Ashraf (Mumahhid al-Dīn) ʿUmar ibn Yūsuf ibn ʿUmar ibn ʿAlī ibn Rasūl". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 66–7. ISBN 9780387310220. (PDF version)

- ^ (King 1983, pp. 547–8)

- ^ Tibbetts, G. R. (1973). "Comparisons between Arab and Chinese Navigational Techniques". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 36 (1): 97–108 [105–6]. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00098013. S2CID 120284234.

- ^ Hirth, Friedrich (1908). Ancient history of China to the end of the Chóu dynasty. New York, The Columbia university press. p. 134.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1962). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 279–80. ISBN 978-0-521-05802-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Minorsky 1937, p. xix.

- ^ Bosworth & Asimov 2003, p. 218–219.

- ^ Minorsky 1937, p. xviii–xix, 5.

- ^ a b Minorsky 1937, p. xviii–xix.

Sources

[edit]- Alavi, S. M. Ziauddin (1965), Arab geography in the ninth and tenth centuries, Aligarh: Aligarh University Press

- Bosworth, C. E.; Asimov, M. S., eds. (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume IV. The age of achievement: A. D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 745. ISBN 9788120815964.

- Douglas, A. Vibert (1973), "Al-Biruni, Persian Scholar, 973–1048", Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 67: 209–211, Bibcode:1973JRASC..67..209D

- Edson, Evelyn; Savage-Smith, Emilie (2004). Savage-Smith, Emilie (ed.). Medieval Views of the Cosmos. Oxford: Bodleian Library. ISBN 978-1-85124-184-2.

- King, David A. (1983), "The Astronomy of the Mamluks", Isis, 74 (4): 531–555, doi:10.1086/353360, S2CID 144315162

- King, David A. (2002), "A Vetustissimus Arabic Text on the Quadrans Vetus", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 33: 237–255, doi:10.1177/002182860203300302, S2CID 125329755

- King, David A. (December 2003), "14th-Century England or 9th-Century Baghdad? New Insights on the Elusive Astronomical Instrument Called Navicula de Venetiis", Centaurus, 45 (1–4): 204–226, doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.2003.450117.x

- King, David A. (2005), In Synchrony with the Heavens, Studies in Astronomical Timekeeping and Instrumentation in Medieval Islamic Civilization: Instruments of Mass Calculation, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-14188-X

- McGrail, Sean (2004), Boats of the World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-927186-0

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1937). Hudud al-'Alam, The Regions of the World A Persian Geography, 372 A.H. – 982 A.D. translated and explained by V. Minorsky (PDF). London: Luzac & Co. p. 546.

- Mott, Lawrence V. (May 1991), The Development of the Rudder, A.D. 100-1337: A Technological Tale, Thesis Archived 2017-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, Texas A&M University

- Pingree, David (2010b). "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iv. Geography". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis (1996), Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, vol. 1 & 3, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12410-7

- Sezgin, Fuat (2000), Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums X–XII: Mathematische Geographie und Kartographie im Islam und ihr Fortleben im Abendland, Historische Darstellung, Teil 1–3 (in German), Frankfurt am Main

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

[edit]Geography and cartography in the medieval Islamic world

View on GrokipediaBackground and Influences

Hellenistic and Pre-Islamic Foundations

The Hellenistic tradition laid the groundwork for systematic geography and cartography in the medieval Islamic world through key works that emphasized empirical observation, mathematical precision, and global conceptualization. Strabo's Geography, composed around the early 1st century CE, provided a comprehensive descriptive account of the known world, drawing on travel itineraries, historical narratives, and regional ethnographies to outline the oikoumene from Europe to India; this qualitative approach influenced later Islamic geographers in their emphasis on integrating textual descriptions with spatial understanding. Marinus of Tyre, active in the late 1st to early 2nd century CE, advanced quantitative methods by proposing a rectangular grid system of meridians and parallels to plot locations using latitude and longitude, marking the first systematic use of such coordinates for world mapping; although critiqued by successors, this framework facilitated the transition from descriptive to coordinate-based cartography. Claudius Ptolemy's Geographia, written circa 150 CE, synthesized these ideas into an authoritative compendium, cataloging coordinates for approximately 8,000 places across three continents, employing conical and modified equatorial projections to represent the spherical Earth on flat surfaces, and establishing prime meridians and parallels for global reference.[6] The transmission of Ptolemy's Geographia to the Islamic world occurred through Arabic translations in the 9th century, profoundly shaping early medieval cartographic practices. One of the earliest and most influential adaptations was by the scholar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (c. 780–850 CE), whose Kitāb Ṣūrat al-Arḍ (Book of the Image of the Earth) integrated Ptolemaic coordinates with Persian, Indian, and local data, providing latitudes and longitudes for 2,402 localities while correcting place names and positions relevant to the Abbasid realm; this work, produced under the patronage of Caliph al-Maʾmūn, included descriptions of cities, rivers, mountains, and seas, serving as a foundational text for constructing world maps. Al-Khwārizmī retained Ptolemy's degree length of 66 2/3 miles but adjusted key coordinates based on contemporary astronomical observations, such as correcting the length of the Mediterranean Sea. Subsequent translations, such as that by Thābit ibn Qurra (d. 901 CE), further disseminated Ptolemy's methods, enabling Islamic scholars to build upon the Greek system's emphasis on mathematical geography for both theoretical and practical applications.[7][6][1] Pre-Islamic contributions from Babylonian and Persian civilizations provided early precedents in conceptual and administrative mapping that complemented Hellenistic advances. The Babylonian World Map, known as Imago Mundi—a clay tablet from the 6th century BCE—depicts a circular cosmos centered on Babylon, surrounded by the Euphrates River, known regions like Assyria and Urartu, and mythical outer lands beyond a "Bitter River" (representing the ocean); this schematic representation, inscribed with cuneiform descriptions of distant peoples and places, illustrates an early cosmological geography blending real and mythical elements, influencing later views of the world as a bounded, central domain. In the Persian sphere, the Achaemenid and Sassanid empires (6th century BCE to 7th century CE) developed sophisticated administrative geographies, including detailed itineraries along the Royal Road network spanning over 2,500 kilometers from Susa to Sardis, which facilitated governance, taxation, and military logistics through recorded distances and waypoints; Sassanid administrators divided the empire into four kusts (quarters)—north, south, east, and west—for fiscal and provincial management, supported by cadastral surveys and route descriptions in texts like the Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr, laying groundwork for empirical spatial organization. These traditions emphasized practical utility over abstract projection, offering Islamic geographers models for regional delineation and travel-based knowledge.[8][9] Islamic scholars adapted these foundations by addressing inaccuracies in Ptolemy's data through rigorous astronomical verification, particularly in longitude measurements. Ptolemy's longitudes, derived from estimated travel times and eclipse observations, often overstated distances; for instance, he calculated the Mediterranean Sea as spanning 62 degrees, whereas actual astronomical fixes revealed it to be about 52 degrees, a correction of roughly 10 degrees achieved by timing lunar eclipses and stellar alignments across known sites. Using instruments like the astrolabe and data from observatories such as that in Baghdad, scholars refined coordinates for key locations, enhancing the accuracy of world maps and itineraries while preserving the Greek grid system for broader integration with Persian administrative traditions.[10][11][2]Integration of Persian, Indian, and Other Traditions

Islamic geographers in the medieval period synthesized knowledge from diverse Eastern traditions, complementing Hellenistic foundations to form a comprehensive worldview that emphasized practical navigation, administrative utility, and astronomical precision. This integration occurred primarily through conquests, trade networks, and scholarly translations during the early Abbasid era, enabling the adaptation of non-Greco-Roman elements into Islamic scholarship.[12] Persian influences were prominent in the adoption of Sassanid administrative and cartographic practices by the early Abbasid caliphate. The Middle Persian text Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr, a surviving Sassanid geographical work detailing provincial capitals, road systems, and territorial divisions, provided a model for organizing the vast Islamic empire's provinces and itineraries. Sassanid road maps, which mapped key routes from Mesopotamia to Khorasan and beyond, informed Abbasid postal and military networks, ensuring continuity in infrastructural planning across the conquered territories. These elements were incorporated into early Islamic works on routes and regions, blending Persian spatial organization with emerging Arabic descriptive methods.[13] Indian contributions enriched Islamic understandings of spherical geometry and computational tools essential for cartographic projections. Following the Umayyad conquest of Sindh in 711 CE, Indian astronomical texts became accessible, with key works by Aryabhata and Brahmagupta translated into Arabic in the late 8th century under Abbasid patronage. Brahmagupta's Brahmasphutasiddhanta (translated as Sindhind around 773 CE) introduced concepts of a spherical Earth and trigonometric functions, including sine tables that facilitated accurate map projections and latitude calculations. These innovations supported the development of Islamic geographic treatises that required precise measurements for depicting curved surfaces and distances.[14] Chinese elements entered Islamic geography via Silk Road exchanges, particularly influencing navigational techniques for monsoon-dependent voyages. African and Byzantine inputs provided vital data on peripheral trade networks, drawn from direct maritime interactions. Islamic geographers incorporated detailed accounts of East African coastal routes, including ports from Somalia to Zanzibar, as described in al-Mas'udi's 10th-century Meadows of Gold, which outlined exports of ivory, gold, and slaves along monsoon paths. Similarly, Byzantine portolan-style charts, emphasizing Mediterranean coastal details and wind roses, influenced Islamic adaptations through shared seafaring communities, enabling precise depictions of harbors and currents in regional maps. These contributions rounded out the Islamic geographic corpus with empirical observations from African and Levantine trade.[15][16]Historical Development

Early Period (8th-9th Centuries)

The early period of geography and cartography in the medieval Islamic world, during the 8th and 9th centuries under the Abbasid Caliphate, was marked by institutional patronage that facilitated the translation of ancient texts and the initiation of empirical measurements. The House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma) in Baghdad, established around 830 CE by Caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833 CE), served as a major intellectual center where scholars translated Greek, Persian, and Syriac works on science, including geographical treatises, into Arabic.[17] Al-Ma'mun commissioned expeditions to acquire manuscripts from distant regions, such as the Byzantine Empire and India, and supported collaborative research in astronomy and mathematics, which directly informed cartographic advancements.%20Jun.%202019/37%20JSSH-2328-2017.pdf) This institutional framework, building briefly on Hellenistic sources like Ptolemy's Geography, enabled the synthesis of inherited knowledge with new observations.[18] A pivotal achievement was al-Ma'mun's sponsorship of the first known empirical measurement of the Earth's meridian arc around 827 CE, conducted by teams of astronomers in the Syrian desert. One expedition, led by Sind ibn Ali and others, measured the distance between Sinjar (north of Mosul) and a point southward where the noon solar altitude differed by one degree, yielding approximately 56 Arabic miles per degree of latitude.[19] A parallel effort near Palmyra (Tadmor) produced a slightly higher value of 57 Arabic miles, but the accepted result was an average of 56 2/3 Arabic miles (equivalent to about 111.7 kilometers per degree), remarkably close to modern estimates.[19] These measurements, using astronomical observations and chained ropes for distance, provided a foundational scale for Islamic world maps and corrected earlier approximations.[19] Al-Khwarizmi (d. ca. 847 CE), working under al-Ma'mun's patronage at the House of Wisdom, produced the Kitab Surat al-Ard (Book of the Image of the Earth) around 830 CE, a seminal geographical text that revised Ptolemy's coordinates for over 2,400 localities.[18] This work included tables of longitudes and latitudes, with the known world spanning approximately 70 degrees in longitude from the western limits near the Atlantic to eastern Asia, adjusting Ptolemy's inflated estimates—such as reducing the Mediterranean's length from 54 degrees to 43 degrees 20 minutes.[18] Accompanied by maps in later manuscripts, it emphasized practical utility for navigation and administration, marking the transition from textual descriptions to coordinate-based cartography.[20] Complementing these efforts, Ibn Khordadbeh (d. ca. 912 CE) compiled the Kitab al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik (Book of Roads and Kingdoms) around 870 CE, an itineraries-based geographical compendium focused on the Abbasid Empire's administrative and trade networks.[21] The text details routes connecting major cities, provinces, and frontiers, with distances measured in farsakhs (approximately 5.6 kilometers each), alongside descriptions of regions, peoples, resources, and postal systems.[21] Drawing on official records and traveler accounts, it provided essential logistical data without extensive mapping, influencing later periegetic traditions in Islamic geography.[21]Flourishing Schools (10th-12th Centuries)

During the 10th to 12th centuries, Islamic geography saw the institutionalization of distinct scholarly traditions that built upon earlier foundations, emphasizing practical knowledge for administration, trade, and pilgrimage. The Khordadbeh-Jayhani tradition, forming around 900 CE, marked a significant evolution in this period by prioritizing detailed global itineraries and trade routes across the Islamic world and beyond. Originating from the works of Ibn Khordadbeh (ca. 820–911 CE), a Persian official under the Abbasids, this tradition integrated administrative records, traveler accounts, and Persian sources to describe postal and caravan paths, including distances between stages and extensions to regions like China via sea routes.[18] Jayhani (ca. 930 CE), a Samanid vizier in Central Asia, further advanced this approach in his now-lost geographical compendium, which influenced subsequent Perso-Arab scholarship by blending practical route descriptions with broader cosmological elements drawn from Quranic and folk traditions.[18] These efforts provided a textual framework that encouraged the transition toward more visual representations in later schools. Parallel to this, the Balkhi school emerged as a prominent cartographic tradition in the early 10th century, centered in Baghdad and Balkh, where scholars synthesized Hellenistic, Persian, and indigenous Islamic perspectives. Founded by Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (d. 934 CE), a native of Balkh who studied in Baghdad under al-Kindi, the school produced the earliest surviving Islamic atlases, featuring rectangular maps organized around climatic zones known as iqlim.[22] These zones divided the known world into provinces, with maps depicting roughly rectangular areas enclosed by seas or mountains, highlighting key features like rivers, deserts, and trade paths to aid regional understanding.[22] The school's emphasis on visual aids complemented textual descriptions, reflecting a shift toward systematic regional analysis that supported governance in the expanding Islamic empire.[23] Istakhri (fl. ca. 950 CE), a key figure in the Balkhi school, refined these methodologies through revisions to al-Balkhi's foundational texts, introducing innovative color-coded regional maps that enhanced clarity and accessibility. In his Kitab al-Masalik wa-al-Mamalik, Istakhri incorporated colored elements—such as red for caravan routes, blue for rivers, and green for seas—across maps of approximately 17 provinces, drawing from earlier route-based works while adding personal observations from travels in Persia and Iraq.[23] These revisions standardized the Balkhi style, making geographical knowledge more practical for merchants and officials by visually integrating topography with itinerary details.[22] Al-Muqaddasi (ca. 946–991 CE) further specialized the Balkhi tradition with a focus on qualitative regional analysis, informed by extensive personal travels spanning over 20 years across the Islamic lands from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. Completing his Ahsan al-Taqasim fi Ma'rifat al-Aqalim around 985 CE in Shiraz, he divided the Muslim world into 14 iqlim (climatic regions), providing vivid, firsthand descriptions of each that encompassed physical features, urban life, cultural practices, fiscal systems, and environmental conditions, often critiquing earlier sources for inaccuracies.[24] His approach emphasized human geography, using symbolic maps to illustrate qualitative aspects like architecture and hydrology, thereby enriching the school's descriptive depth without relying solely on quantitative measurements from the prior century.[23]Later Innovations (13th-16th Centuries)

The Mongol Ilkhanate's patronage under rulers like Ghazan Khan (r. 1295–1304) and Öljaitü (r. 1304–1316) fostered significant advancements in geographic scholarship, exemplified by Rashid al-Din's Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh (Compendium of Chronicles), completed around 1308. This pioneering world history integrated detailed descriptions of Asia and Europe, drawing on Mongol, Chinese, and Islamic sources to provide accounts of regions such as the Great Wall of China, political divisions in Yuan territories (Cathay, Chin, and Machin), and key urban centers like Khanbaligh (Beijing) and Khingsai (Hangzhou). Although the planned third volume, The Routes of the Realms, which was to include world maps like The Map of the Climates, is lost, the work's geographic sections marked a shift toward a more interconnected Eurasian perspective, reflecting the Ilkhanate's role in cross-cultural knowledge exchange.[12] Building on Ilkhanate influences, Mamluk scholar Ibn Fadlallah al-ʿUmari (1301–1349) compiled Masālik al-Abṣār fī Mamālik al-Amṣār (Ways of Perception in the Provinces of the Lands) around 1340, offering vivid descriptions of Yuan China derived from traveler accounts along land routes. Al-ʿUmari referred to southern China as "Sin al-Sin" (China of China), detailing cities such as Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and Hangzhou, along with aspects of Yuan administration, society, and maritime trade hubs frequented by Muslim merchants. His work updated earlier Islamic geographic traditions, such as those of al-Khwārizmī, by incorporating contemporary reports from informants who had visited the Yuan court, thereby enhancing Muslim understandings of East Asian geography amid expanding Indian Ocean networks.[12][25] Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s Riḥla (Travel Narrative), dictated around 1355 after nearly three decades of journeys covering approximately 120,000 km across Africa, Asia, and the Indian Ocean, provided empirical updates to regional geography that influenced subsequent Islamic cartographic efforts. His detailed itineraries documented physical landscapes, sacred sites, water sources, and urban routes, bridging classical Greek-Islamic traditions with firsthand observations and aiding the refinement of descriptive maps in later works. These accounts, spanning from Morocco to China, contributed to a more accurate portrayal of interconnected Muslim territories, emphasizing practical navigation amid the political fragmentation following the Mongol era.[26] Ottoman expansions in the 15th and 16th centuries spurred innovative cartographic syntheses, most notably in Pīrī Reis's 1513 world map, which combined Portuguese nautical charts, a lost Columbus map, and Islamic geographic sources to depict the Atlantic coasts of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Presented to Sultan Selim I after the 1517 conquest of Egypt, this gazelle-skin portolan chart integrated eyewitness seafaring data from Pīrī Reis's voyages since the 1480s with textual annotations on New World discoveries, surpassing contemporary European charts in coastal detail. As part of the broader Ottoman tradition, seen in Pīrī Reis's Kitāb-ı Baḥriye (Book of Navigation, 1521) with its 214 portolan-style maps, these advancements reflected the empire's strategic adaptation of earlier Balkhi School methods to military and maritime needs.[27]Major Cartographic Traditions

Khordadbeh-Jayhani Tradition

The Khordadbeh-Jayhani tradition represents an early phase in medieval Islamic geography, characterized by a practical, itinerary-based approach that emphasized linear descriptions of overland and maritime routes spanning the known world, from China to al-Andalus.[18] This methodology focused on compiling sequential accounts of travel paths, including distances measured in stages (marhalah) or parasangs, estimated tolls and customs duties at key points, and logistical details for administration and trade, drawing from official records like those of the barid postal system.[18] Such descriptions served immediate utilitarian purposes, such as facilitating military movements, pilgrimage coordination, and commercial exchanges, rather than advancing theoretical models of the earth's form or climate zones, though they occasionally referenced the seven climes (iqlim) derived from Hellenistic influences.[18] Ibn Khordadbeh, a Persian official in the Abbasid administration around 870 CE, laid the foundational influence for this tradition through his Kitab al-Masalik wa-al-Mamalik (Book of Routes and Provinces), the earliest surviving exemplar of the genre.[18] As director of the barid, he integrated postal route data to outline major arteries of the Islamic world, extending beyond Muslim territories to include sea routes to China and lists of merchandise transported along them, such as spices, textiles, and slaves, highlighting economic interconnections.[18] His work, revised multiple times up to circa 885 CE, provided distances in practical units—often one marhalah equating roughly a day's journey—and noted toll collection points, underscoring the tradition's administrative orientation.[18] Building on this, Abu Abdallah al-Jayhani, a Samanid vizier in Khorasan around 910 CE, advanced the tradition by compiling a comprehensive geographical compendium that synthesized reports from numerous travelers, merchants, and officials, reportedly exceeding thirty sources in scope.[18] Though his original text is lost, later geographers like al-Muqaddasi praised it as the most authoritative of its time for its detailed coverage of routes across the seven climes, from equatorial regions to temperate zones up to 50°30' latitude, incorporating ethnographic notes on distant peoples and lands.[18] Al-Jayhani's effort emphasized empirical aggregation over innovation, preserving oral and written accounts to map global connectivity under Samanid patronage. Despite its influence on subsequent works, the Khordadbeh-Jayhani tradition exhibited notable limitations, remaining predominantly text-heavy with minimal or no surviving illustrations, as maps were not integral to the itinerary format.[18] Distances and toll estimates, while useful for practical navigation, often lacked mathematical precision and consistency, reflecting reliance on variable traveler testimonies rather than standardized surveys.[18] This focus on administrative utility over cosmological theory positioned it as a precursor to more visually oriented schools, but it prioritized functional knowledge for governance and commerce in the expanding Islamic oikoumene.[18]Balkhi School

The Balkhi School, a prominent tradition in medieval Islamic cartography, was founded by the Persian scholar Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (d. 934 CE) in the early 10th century. Al-Balkhi's seminal work, Surat al-aqalim (Images of the Regions), composed around 921 CE, established a systematic approach to mapping the Islamic world by integrating physical geography with religious and cultural significance, such as highlighting pilgrimage sites and mosques alongside natural features. Although no original manuscripts of al-Balkhi's atlas survive, his framework profoundly influenced subsequent geographers, who preserved and expanded his visual methodology.[22] The school's foundational principles centered on dividing the known world into over 20 rectangular maps, known as aqalim, which primarily covered the territories of the Islamic empire from al-Andalus to Transoxania. These divisions were adapted from Ptolemy's seven climatic zones—latitude-based bands defined by varying day lengths—but reoriented to emphasize political and regional boundaries rather than strict astronomical coordinates. Later exemplars, such as those by al-Istakhrī and Ibn Ḥawqal, typically included 21 such maps, each depicting a province or cluster of regions with a uniform schematic style: north-up orientation, stylized representations of rivers as parallel blue lines, mountains as yellow triangular chains, and towns as simple dots, deliberately avoiding latitude and longitude grids to prioritize accessibility and symbolic clarity over mathematical precision.[18][22][28] This visual, climate-based system evolved through the 10th to 14th centuries, contrasting with earlier itinerary-focused traditions by emphasizing regional overviews in illustrated atlases. By the 14th century, Hamdallah Mustawfi (d. after 1340 CE) incorporated the Balkhi mapping style into his Nuzhat al-qulūb (The Pleasure of Hearts, c. 1330 CE), adding descriptive texts enriched with Persian poetic and literary elements that blended geographical detail with aesthetic and moral reflections on landscapes. These enhancements sustained the school's influence into later Persian cartographic works, maintaining its focus on the core Islamic domains.[22]Regional and Maritime Cartography

Regional and maritime cartography in the medieval Islamic world extended the mapping traditions beyond the core climatic zones of the Islamic heartlands, focusing on peripheral regions and oceanic expanses to support trade, exploration, and navigation. Building on the regional styles of the Balkhi School, these maps emphasized practical details for distant voyages, incorporating coastal features, ports, and navigational aids derived from sailor reports and empirical observations.[29] Al-Idrisi's Tabula Rogeriana (c. 1154 CE), commissioned by Roger II of Sicily, featured detailed coastal outlines of Africa and the Indian Ocean, highlighting key ports such as those along the Swahili and Malabar coasts. These representations drew from Muslim mariners' experiences, depicting the Indian Ocean as an open sea rather than Ptolemy's enclosed basin, and included notations on prevailing winds essential for monsoon navigation. The maps integrated ports like Zanzibar and Calicut, facilitating trade routes across the "Great Arab Lake" that connected East Africa to South Asia.[30][31][29] In Central Asia, Mahmud al-Kashgari's linguistic map in Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk (c. 1074 CE) provided a unique ethnolinguistic representation of Turkic territories, oriented with east at the top and centered on Turkish-speaking regions from the borders of Kyrgyzstan to Xinjiang. This schematic map illustrated tribal distributions, rivers, mountains, and deserts using color coding—red for mountains, yellow for sand, blue for rivers, and green for seas—while incorporating Turkic place names and dialects to document cultural geography amid expanding caliphal influences. It served both scholarly and propagandistic purposes, portraying Turkic lands as central to the Islamic world.[32][33] Maritime innovations appeared in anonymous 14th-century portolan-style charts, such as the "Maghreb Chart" (ca. 1330 CE), which adapted European models with Arabic toponymy for Mediterranean navigation. This chart, measuring 24 x 17 cm and covering latitudes 33°–55°N and longitudes 10°W–11°E, featured 16 radiating rhumb lines emanating from compass roses, enabling sailors to plot courses using wind directions with an average magnetic declination of about 6°. It listed 202 place names, including 48 of Arab origin, written perpendicular to coastlines, and employed a scale of 100 "miles" (approximately 1.9 statute miles), prioritizing coastal accuracy over interior details for practical seafaring.[16] The Book of Curiosities (Kitāb al-Ḥafāʾ al-Ḥāsib, c. 1200 CE), an anonymous Fatimid cosmographical treatise, showcased fantastical sea maps that blended empirical and mythical elements, including stylized depictions of islands and oceans. Its 17 maps featured unique portrayals of the Mediterranean's coasts and islands like Soqotra, noted for its "black pirates," alongside schematic views of Sicily, Cyprus, Tinnīs, and al-Mahdīya with artistic flourishes such as exaggerated island shapes and wondrous sea creatures. These illustrations, drawn from 10th- and 11th-century sources, highlighted rare cosmographic details, such as river systems and celestial influences on seas, distinguishing them from standard geographic works.[34][35]Key Works and Maps

Book on the Appearance of the Earth

The Book on the Appearance of the Earth (Arabic: Kitāb ṣūrat al-arḍ), completed by Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī around 833 CE, is an early foundational text in Islamic mathematical geography. Drawing on the recently translated Geography of Ptolemy, it provides a systematic revision and expansion of classical knowledge, compiling latitude and longitude coordinates for 2,402 localities across the known world, organized into 18 regional sections covering areas from the Iberian Peninsula to China. Each section includes textual descriptions of provinces, cities, mountains, rivers, seas, and islands, with distances between places and notes on climates and populations, emphasizing practical utility for travelers and administrators.[36][1] The work introduces a new prime meridian based on the Fortunate Islands (Canary Islands), shifting from Ptolemy's Canary-based but differently calculated system, and corrects numerous errors in the Greek original, such as inflated sizes of Asia and Europe. While the original manuscript likely consisted primarily of tables and text without illustrations, surviving 11th- and 12th-century copies include a world map on a rectangular projection and 21 regional maps depicting features like the Nile River with early schematic outlines, using color for water (blue) and land (green/brown). These maps represent one of the earliest attempts in Islamic cartography to visualize coordinate data, influencing subsequent works like those of the Balkhī school.[30][37] Al-Khwārizmī's compilation relied on Ptolemaic data cross-verified with contemporary Islamic sources, including traveler reports and astronomical observations, resulting in more accurate Eurasian dimensions and Mediterranean coastlines. This empirical approach advanced descriptive and mathematical geography (jughrāfiyā), serving as a bridge between Hellenistic traditions and Abbasid scholarship, and was widely copied and adapted in the Islamic world for centuries.[36][1]Tabula Rogeriana

The Tabula Rogeriana, also known as the Book of Roger, is a renowned 12th-century world atlas created by the Moroccan-Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi for the Norman king Roger II of Sicily. Completed in 1154 after approximately 15 years of collaborative work involving scholars, travelers, and data compilation, it represents a pinnacle of medieval Islamic cartography, synthesizing diverse geographical knowledge into a systematic visual representation. Al-Idrisi drew upon Ptolemaic traditions, earlier Islamic works, and contemporary observations, including coordinates derived from astrolabe measurements, to produce this atlas, which was originally crafted as both a large silver planisphere (approximately 80 inches in diameter) and an accompanying manuscript with sectional maps.[38][39][30] The atlas's core composition consists of 70 sectional maps, organized into seven latitudinal "climates" (each subdivided into ten longitudinal sections), which together form a rectangular world map encompassing Eurasia and North Africa, with the southern hemisphere oriented at the top and Mecca positioned near the center. These maps, rendered in a stylized, non-perspective style typical of Islamic cartography, depict physical features such as rivers, mountains, and coastlines alongside urban centers, trade routes, and political boundaries, complemented by extensive textual descriptions in the accompanying volume. Accuracy is particularly notable in well-traveled regions: the Nile Delta is portrayed with precise branching and settlements, while the Iberian Peninsula's southwestern coast reflects detailed Norman reconnaissance, correcting earlier distortions like Ptolemy's overestimation of the Mediterranean's length to about 42 degrees. In contrast, unexplored southern and eastern areas incorporate mythical elements, such as the Mountains of the Moon as the Nile's source, blending empirical data with inherited lore to fill informational gaps.[38][39][30] The production process, commissioned in 1138 at Roger II's Palermo court—a multicultural hub of Islamic, Byzantine, and Latin scholarship—involved al-Idrisi leading a team that interrogated merchants, diplomats, and explorers while cross-verifying information against astrolabe-derived latitudes and longitudes. The silver disk, engraved for durability and display, symbolized the project's prestige, though only textual and derivative map copies survive today, with ten known manuscripts, including one at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Its influence extended through Latin translations in the 15th century, which disseminated al-Idrisi's framework across Europe, serving as a foundational reference for cartographers like Abraham Ortelius and remaining the most authoritative world depiction until Portuguese explorations in the 16th century.[38][39][30]Piri Reis Map and Other Late Works

The Piri Reis map, compiled in 1513 CE by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis, represents a pinnacle of late medieval Islamic cartography through its integration of diverse global sources into a cohesive portolan-style representation. This surviving fragment, approximately one-third of the original, depicts the Atlantic Ocean, western coasts of Europe and Africa, and the Americas, including detailed outlines of South America, the Caribbean islands such as Hispaniola and Cuba, and parts of Central America.[40] The map employs characteristic portolan features like rhumb lines and compass roses for navigation, while incorporating Islamic iconographic elements such as Arabic inscriptions, fantastical creatures, and painterly embellishments drawn from classical traditions. Piri Reis explicitly noted that the map drew from over 20 cartographic sources, blending Islamic, Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish materials to achieve unprecedented accuracy for its time. Among these were eight Ptolemaic-derived Ja‘fariyyah maps from the Islamic tradition, an Arabic map of India, four recent Portuguese charts, and crucially, a map attributed to Christopher Columbus, likely derived from his 1498 voyages and obtained through a captured Spanish pilot.[40] This synthesis allowed the map to portray the newly discovered Americas not as mythical lands but as navigable extensions of the known world, reflecting Ottoman maritime ambitions in the Indian Ocean and beyond.[41] Another significant late work is the atlas attributed to Ibn al-Wardi, circulating in manuscripts around 1440 CE, which features a circular world map emblematic of the Khordadbeh-Jayhani tradition's enduring influence. Centered on Mecca and Medina, the map divides the oikumene into climatic zones, with the northern sectors illustrating China and India, the southern regions denoting Christian territories and sub-Saharan Africa, and the encircling ocean (Bahr al-Muhit) enclosing the inhabited world.[3] Later Ottoman copies, such as one dated 1593 CE, adapted these designs to highlight expanding imperial territories, including European conquests and Indian Ocean routes, while retaining the schematic, symbolic style over precise topography.[42] The Hajji Ahmed map, produced around 1559 CE in Venice by the Tunisian cartographer Hajji Ahmed, exemplifies further evolution through its innovative heart-shaped (cordiform) projection, a form popularized in European cartography but adapted for Ottoman audiences. This large-scale world map, carved on wooden blocks for printing, encompasses the entire known world in a spherical yet stylized form, with the Americas depicted as distinct landmasses emerging from Columbus-era discoveries.[43][44] It incorporates Western influences like Venetian toponyms alongside Arabic and Turkish labels, underscoring cross-cultural exchanges in Mediterranean scholarly circles. These late works highlight key innovations in medieval Islamic cartography, particularly the incorporation of New World discoveries into established frameworks, transforming static Islamic mappaemundi into dynamic tools for imperial expansion. By fusing portolan precision with symbolic Islamic cosmology—evident in Piri Reis's eclectic sourcing and Hajji Ahmed's hybrid projection—these maps bridged pre-modern traditions with emerging global awareness, influencing Ottoman navigation and diplomacy.[40][44]Instruments and Techniques

Astrolabe and Astronomical Instruments

The astrolabe served as a pivotal astronomical instrument in the medieval Islamic world, enabling precise observations that supported geographic and cartographic endeavors. Primarily constructed as a planispheric model, it featured a flat brass disk known as the mater, which housed interchangeable plates tailored to specific latitudes, depicting the local horizon, almucantars, and hour circles. Over these plates rotated the rete, a skeletal disk engraved with pointers representing the positions of major stars and the zodiacal ecliptic, allowing users to simulate the night sky's rotation. On the reverse, an alidade—a straightedge with adjustable sighting vanes—facilitated direct measurements of celestial altitudes or terrestrial elevations by aligning sights along the horizon or a distant object.[45] Islamic artisans refined the astrolabe's design to incorporate religious and practical necessities, notably adding qibla scales on the mater's back for determining the direction to Mecca from any location. These scales, often calibrated in degrees of azimuth relative to the local meridian, used inscribed grids of latitudes (typically from 10° to 50° north) and longitudes (up to 60° east or west of Mecca) to compute the qibla angle via stereographic projection, drawing on geographic coordinates of over 30 cities compiled in gazetteers on the instrument. Such adaptations, evident in instruments from 10th-century Baghdad and later Persian workshops, transformed the astrolabe into a tool for both devotion and spatial orientation, with engravings sometimes including Qur'anic verses on divine knowledge of the heavens. The basic idea for a latitude-independent (universal) astrolabe was conceived in the 9th century by Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi in Baghdad.[46][45][47] A notable example is the work of the 10th-century Syrian artisan Mariam al-Ijliya (also known as Mariam al-Asturlabi), who crafted precise astrolabes in Aleppo under the Hamdanid court, improving engraving precision and observational accuracy as documented in historical accounts. Complementing these was Al-Biruni's ring astrolabe, described circa 1000 CE in his astronomical treatises, which consisted of interconnected rings suspended from a thumb ring, enabling compact altitude measurements without bulky components—ideal for field use in geographic surveys.[48] In geographic applications, the astrolabe excelled at ascertaining latitude by measuring the meridian altitude of Polaris (for northern latitudes) or the sun at noon, providing essential coordinates for plotting locations on maps; for instance, observers could derive a site's latitude to within 0.5° accuracy under clear skies. Longitude differences were approximated by comparing local times of celestial events, such as lunar culminations, with those recorded at a reference meridian like Baghdad, facilitating relative positioning across vast territories. These measurements informed map projections, where angular data from the rete and alidade helped construct coordinate grids, as Al-Biruni utilized in his orthographic cylindrical projection for regional charts. Astrolabes thus bridged astronomy and cartography, underpinning explorations from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean.[45][49]Compass and Navigation Tools

In the medieval Islamic world, the magnetic compass emerged as a pivotal navigation tool, with the earliest documented reference appearing in the Persian anthology Jāmi‘ al-ḥikāyāt wa-l-naẓāʾir by Sadīd al-Dīn Muḥammad ‘Awfī around 1232–1233 CE, describing a floating (wet) compass consisting of an iron fish in a water-filled bowl used to determine direction during a voyage in the Red Sea or Persian Gulf.[50] This wet variant, influenced by Chinese navigational technology transmitted through Indian Ocean trade routes, featured a magnetized needle suspended in liquid to indicate magnetic south, facilitating orientation in maritime contexts.[51] By the late 13th century, the Yemeni Sultan al-Ashraf ‘Umar (r. 1295–1296 CE) detailed a similar wet compass in his astronomical treatise Mu‘īn al-ṭullāb, primarily for determining the qibla (direction to Mecca), though its utility extended to sea travel.[50] The dry compass, employing a pivoting needle without liquid, first appeared in the early 14th century in the work of the Egyptian astronomer Ibn Sim‘ūn (ca. 1300 CE) in Kanz al-yawāqīt, marking an advancement for more stable land and sea use.[50] Navigators in the Islamic world applied the compass alongside dead reckoning techniques, estimating position through speed, time, and course to maintain bearings during open-sea voyages, particularly in the Indian Ocean trade networks connecting the Arabian Peninsula, East Africa, India, and Southeast Asia.[52] Rhumb line sailing, which followed constant compass directions (e.g., 32 wind-based points) rather than great-circle paths, became standard for these routes, enabling efficient monsoon-driven trade in spices, textiles, and porcelain from the 9th to 15th centuries.[53] Such methods relied on the compass to sustain steady headings over long distances, compensating for the lack of longitude determination and integrating with seasonal wind patterns for reliable passage.[52] Complementing the compass were simpler sighting tools like the kamal, a rectangular wooden board with knotted strings used to measure the altitude of the Pole Star above the horizon at night, allowing latitude fixes in the 10° to 30° N range critical for Indian Ocean crossings.[54] The quadrant, or rub‘, a quarter-circle plate with degree markings and a plumb line, served to gauge solar or stellar altitudes during the day for precise elevation readings, aiding in latitude verification amid variable weather.[55] These instruments, often portable and constructed from wood or brass, were essential for pilots navigating without advanced celestial tables. In the Mediterranean and Red Sea, Islamic navigators integrated compass readings with portolan charts—detailed coastal maps featuring rhumb lines radiating from wind roses—to plot routes between ports like Alexandria, Constantinople, and Aden, supporting military campaigns and commerce from the 14th century onward, as exemplified in Ottoman works like Pīrī Reʾīs's Kitāb-i Baḥrīye (1521–1526 CE).[16] This combination enhanced dead reckoning accuracy for galley-based travel, where compass stability was vital for threading narrow straits and avoiding hazards.[16]Mathematical Projections and Methods

In medieval Islamic cartography, mathematical projections and methods advanced the representation of the Earth's spherical surface on flat maps, drawing on Greek, Indian, and indigenous innovations to achieve greater precision in geographic computations. The Balkhi school, prominent from the 10th century, employed the equirectangular projection—a simple cylindrical system where meridians and parallels form a uniform grid of straight lines, preserving angles but introducing distortion in scale away from the equator. This approach, described in works like Suhrab's late 10th-century treatise, facilitated the plotting of regional maps without complex corrections, prioritizing political boundaries over spherical accuracy, as seen in the rectangular outlines of provinces in Istakhri's Kitab al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik.[2] Al-Biruni (973–1048 CE), in his treatise Istīhrāj al-wujūh al-mumkinah fī ṣanʿat al-asṭurlāb (c. 1005 CE, with further developments around 1030 CE), provided early hints at pseudoconic projections for converting spherical coordinates to planar ones, including a globular conic method where meridians are curved arcs converging toward the poles, akin to later European pseudoconic designs like the Werner projection. This technique aimed to minimize distortion in mid-latitudes by treating the sphere as a cone tangent at a standard parallel, allowing for more faithful representations of areas and shapes in world maps, as reconstructed from his descriptions of rolling a globe onto paper.[56][57] Islamic scholars refined Ptolemy's coordinate system, originally limited to about 2–3° accuracy, to within 1° for many locations by integrating sine functions derived from Indian mathematics, such as those in Brahmagupta's Brahmasphutasiddhanta (7th century), which enabled precise calculations of latitudes and longitudes using trigonometric tables. Al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850 CE) initiated this in his revision of Ptolemy's Geography, correcting over 2,400 coordinates through astronomical observations and spherical trigonometry, while al-Biruni further enhanced accuracy by applying sine-based formulas to measure meridian arcs and longitudes, achieving errors as low as 0.5° in key Eurasian sites.[19][56] Distance calculations in Islamic geography approximated great-circle routes—the shortest paths on the sphere—using the farsakh unit, equivalent to approximately 6 km, to convert angular differences into linear measures via spherical excess formulas. Scholars like al-Biruni employed these methods to compute itineraries, such as the Baghdad-to-Ghazni route (about 24° longitude), by dividing the Earth's circumference (refined to approximately 39,840 km) into 360° and applying sine interpolations for oblique paths, enabling practical navigation and map scaling with errors under 5% for long distances.[58][59][60][56] These computations relied on data from astrolabes and quadrants for inputting precise latitudes and longitudes.Notable Geographers

Early and Khordadbeh-Jayhani Figures

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850 CE), a Persian mathematician and geographer active in Baghdad's House of Wisdom, made foundational contributions to Islamic cartography through his Kitab Surat al-Ard (Book of the Image of the Earth), completed around 830 CE under the patronage of Caliph al-Ma'mun.[61] This work provided tabulated longitudes and latitudes for over 2,400 localities, including cities, mountains, rivers, and islands, organized into the classical seven climes and integrating Ptolemaic data with contemporary Muslim observations of regions like the Nile and Indus valleys.[61] Accompanying the text was a world map, known as al-Surat al-Mamuniyya, divided into 38 latitudinal sections, which corrected earlier Greco-Roman inaccuracies and emphasized practical utility for navigation and administration, though the original maps survive only in reconstructions.[61] Ibn Khordadbeh (c. 820–912 CE), a Persian official born in Baghdad, served as director of the caliphal Bureau of Posts and Intelligence, leveraging his role to compile the earliest surviving Arabic administrative geography in Kitab al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik (Book of Roads and Kingdoms), with editions dating to around 846 CE and 885 CE.[21] The text meticulously documents over 930 postal stations, trade routes, and itineraries across the Abbasid Caliphate, extending from the Mediterranean to China and including descriptions of Eurasian paths, climates, peoples, and economic products like spices and silks.[21] His work prioritized logistical details for governance, such as distances between halts and regional taxation potentials, influencing later postal systems and fiscal policies by providing a blueprint for monitoring imperial communications and commerce.[21] Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Jayhani (d. 942 CE), a Samanid vizier and scholar from Transoxiana, extended this itinerary tradition in his lost Kitab al-Masalik wa al-Mamalik (Book of Routes and Kingdoms), a seven-volume compilation drawing on accounts from global travelers, merchants, and diplomats encountered in Bukhara.[62] Active as regent under Emir Nasr II from 914 CE, al-Jayhani synthesized reports on distant lands, focusing on Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Volga region, with details on routes to the Rus, Magyars, and Khazars, including their customs, currencies, and astronomical observations for orientation.[63] Though the original text perished, fragments preserved in later works like those of Ibn Rustah and al-Mas'udi highlight its role in bridging administrative geography with exploratory narratives, enriching knowledge of non-Islamic frontiers.[64] The Khordadbeh-Jayhani figures represent an early phase of Islamic geography centered on administrative and itinerary-based scholarship, emphasizing route networks for postal efficiency, trade oversight, and taxation, which laid groundwork for more descriptive traditions without relying on extensive fieldwork or mathematical projections.[64] Their compilations, rooted in official duties, integrated diverse traveler testimonies to map the caliphal domain's extent, fostering a practical science that supported Abbasid and Samanid expansion while influencing fiscal reforms through precise economic itineraries.[21]Balkhi School Contributors