Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Salah

View on Wikipedia

This article, in the section Sunan ar-Rawatib, may incorporate text from a large language model. (August 2025) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

| Part of a series on Aqidah |

|---|

|

Including: |

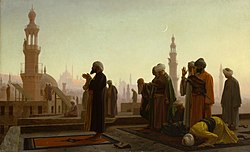

Salah (Arabic: ٱلصَّلَاةُ, romanized: aṣ-Ṣalāh, also spelled Salat), also known as Namaz (Persian: نماز, romanized: namāz), is the practice of formal worship in Islam, consisting of a series of ritual prayers performed at prescribed times daily. These prayers, which consist of units known as rak'ah, include a specific set of physical postures, recitation from the Quran, and prayers from the Sunnah, and are performed while facing the direction towards the Kaaba in Mecca (qibla). The number of rak'ah varies depending on the specific prayer. Variations in practice are observed among adherents of different madhahib (schools of Islamic jurisprudence). The term salah may denote worship in general or specifically refer to the obligatory prayers performed by Muslims five times daily, or, in some traditions, three times daily.[1][2][3]

The obligatory prayers play an integral role in the Islamic faith, and are regarded as the second and most important, after shahadah, of the Five Pillars of Islam for Sunnis, and one of the Ancillaries of the Faith for Shiites. In addition, supererogatory salah, such as Sunnah prayer and Nafl prayer, may be performed at any time, subject to certain restrictions. Wudu, an act of ritual purification, is required prior to performing salah. Prayers may be conducted individually or in congregation, with certain prayers, such as the Friday and Eid prayers, requiring a collective setting and a khutbah (sermon). Some concessions are made for Muslims who are physically unable to perform the salah in its original form, or are travelling.

In early Islam, the direction of prayer (qibla) was toward Bayt al-Maqdis in Jerusalem before being changed to face the Kaaba, believed by Muslims to be a result of a Quranic verse revelation to Muhammad.[4]

Etymology and other names

[edit]The Arabic word salah (Arabic: صلاة, romanized: Ṣalāh, pronounced [sˤa.laːh] or Arabic pronunciation: [sˤə.ɫaːt]) means 'prayer'.[5] The word is used primarily by English speakers to refer to the five daily obligatory prayers. Similar terms are used to refer to the prayer in Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Somalia, Tanzania, and by some Swahili speakers.

The origin of the word is debated. Some have suggested that salah derives from the triliteral root و-ص-ل (w-ṣ-l) which means 'linking things together',[citation needed] relating it to the obligatory prayers in the sense that one connects to Allah through prayer. In some translations, namely that of Quranist Rashad Khalifa, salah is translated as the 'contact prayer',[6] either because of the physical contact the head makes with the ground during the prostration, or again because the prayer connects the one who performs it to Allah. Another theory suggests the word derives from the triliteral root ص-ل-و (ṣ-l-w), the meaning of which is not agreed upon.[7][full citation needed]

In Iran and regions influenced by Persian culture – particularly the Indo-Persian and Turco-Persian traditions – such as South Asia, Central Asia, China, Russia, Turkey, the Caucasus or the Balkans, the Persian word namaz (Persian: نماز, romanized: namāz) is used to refer to salah. This word originates from the Middle Persian word for 'reverence'.[8]

Religious significance

[edit]

The word salah is mentioned 83 times in the Quran as a noun.[9][10]

Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) divides human actions into five categories, known as "the five rulings" (al-aḥkām al-khamsa), and acts of worship will be classified accordingly; mandatory (farḍ or wājib), recommended (mandūb or mustaḥabb), neutral (mubāḥ), reprehensible (makrūh), and forbidden (ḥarām).[11][12] Salah is generally classified into obligatory or mandatory (fard) prayers and supererogatory prayers, the latter being further divided into Sunnah prayers and Nafl prayers.

Hanafi fiqh does not consider both terms as synonymous and makes a distinction between "fard" and "wajib"; In Hanafi fiqh, two conditions are required to impose the fard rule. 1. Nass, (only verses of the Qur'an can be accepted as evidence here, not hadiths) 2.The expression of the text referring to the subject must be clear and precise enough not to allow other interpretations. The term wajib is used for situations that do not meet the second of these conditions.[13] However, this understanding may not be sufficient to explain every situation. For example, Hanafis accept 5 daily prayers as fard. However, some religious groups such as Quranists and Shiites, who do not doubt that the Quran existing today is a religious source, infer from the same verses that it is clearly ordered to pray two or three times,[14][15][16][17][18] not five times. In addition, in religious literature, wajib is widely used for all kinds of religious requirements, without expressing any fiqh definition.

According to riwāya, prayer is held to be extremely important in Islam, and according to all four of the madhabs, those who have a disdain towards prayer are no longer seen as Muslims.[19][20]

While some sects claimed that those killed in this way remained Muslims, others claimed that they had apostatized from the religion. In this case, Islamic duties could not be made for their funerals, they would not be buried in Muslim cemeteries, and their heirs could not claim inheritance rights from the property they left behind, and would be public property.[21] However, even if today's dominant understanding defines the abandonment of worship as sinfulness, does not approve of giving worldly punishment for them. However, in sharia governments, their testimony against a devout Muslim may not be accepted, they may be humiliated and barred from certain positions because of this tag. In practice, since early on in Islamic history, criminal cases were usually handled by ruler-administered courts or local police using procedures which were only loosely related to Sharia.[22][23]

In sermon language, the main purpose of the salah is given as acting as a means of communication with Allah.[24] Other emphases include cleansing the heart, getting closer to God, and strengthening faith. It is believed that the soul requires prayer and closeness to Allah to stay sustained and healthy, and that prayer spiritually sustains the human soul, just as food provides nourishment to the physical body.[25] Tafsir (exegesis) of the Quran can give four reasons for the observation of salah. First, in order to commend God, Allah's servants, together with the angels, do salah ("blessing, salutations").[26][a] Second, salah is done involuntarily by all beings in creation, in the sense that they are always in contact with Allah by virtue of him creating and sustaining them.[27][b] Third, Muslims voluntarily offer salah to reveal that it is the particular form of worship that belongs to the prophets.[c] Fourth, salah is described as the second pillar of Islam.[5]

Performing salah

[edit]

There is consensus on the vast majority of the major details of the salah, but there are different views on some of the more intricate details. A Muslim is required to perform Wudu (ablution) before performing salah,[28][29][30] and making the niyyah (intention) is a prerequisite for all deeds in Islam, including salah. Some schools of Islamic jurisprudence hold that intending to pray suffices in the heart, and some require that the intention be spoken, usually under the breath.[31] The purpose of making the niyyah is to differentiate salah from ordinary routine actions, marking it as an act of worship ('ibāda) rather than a mechanical action ('āda).[32]

The person praying begins in a standing position known as Qiyam, although people who find it difficult to do so may begin while sitting or lying on the ground.[5] This is followed by raising the hands to the head and recitation of the takbir, an action known as the Takbirat al-Ihram (Arabic: تكبيرة الإحرام, romanized: Takbīrat al-Iḥrām). The hands are then lowered, and may be clasped on the abdomen (qabd), or hang by one's sides (sadl). A Muslim may not converse, eat, or do things that are otherwise halal after the Takbirat al-Ihram. A Muslim must keep their vision low during prayer, looking at the place where their face will contact the ground during prostration.[31][33][34]

A prayer may be said before the recitation of the Quran commences. Next, Al-Fatiha, the first chapter of the Quran, is recited. In the first and second rak'a of all prayers, a surah other than Al-Fatiha or part thereof is recited after Al-Fatiha. This is followed by another takbir after which the person praying bows down their waist in a position known as ruku with their hands on their knees (depending on the madhhab, rules may differ for women). While bowing, specific versions of tasbih are uttered once or more. As the worshipper straightens their back, they say the Arabic phrase "سمع الله لمن حمده" (lit. 'Allah hears the one who praises him.'), followed by the phrase "ربنا لك الحمد" (lit. 'Our Lord, all praise is for you.')[31]

Following the recitation of these words of praise, the takbir is recited once again before the worshipper kneels and prostrates with the forehead, nose, knees, palms and toes touching the floor, a position known as sujud. Similar to ruku, specific versions of tasbih are uttered once or more in sujud. The worshipper recites the takbir and rises up to sit briefly, then recites takbir and returns to sujud once again. Lifting the head from the second prostration completes a rak'ah. If this is the second or last rak'a, the worshipper rises up to sit once again and recites the Tashahhud, Salawat, and other prayers.[31] Many Sunni scholars, including Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab[35] and Al-Albani[36] hold that the right index finger should be raised when reciting the prayers in this sitting position,[31] Once the worshipper is done praying in the sitting position in their last rak'a, they perform the taslim, reciting lengthened versions of the Islamic greeting As-salamu alaykum, once while facing the right and another time while facing the left. Taslim represents the end of prayer.[37][38][39]

Mistakes and doubts in salah are compensated for by prostrating twice at the end of the prayer, either before or after the taslim depending on the Madhab. These prostrations are known as sujud sahwi (Arabic: سجود السهو, romanized: Sujud as-Sahw).[40]

Salah in congregation

[edit]In Islamic belief, performing salah in congregation is considered to have more social and spiritual benefits than praying alone.[41] The majority of Sunni scholars recommend performing the obligatory salah in congregation without viewing the congregational prayer as an obligation. A minority view exists viewing performing the obligatory salah in congregation as an obligation.[42]

When praying in congregation, the people stand in straight parallel rows behind one person who leads the prayer service, called the imam. The imam must be above the rest in knowledge of the Quran, action, piety, and justness, and should be known to possess faith and commitment the people trust.[43] The prayer is offered just as it is when one prays alone, with the congregation following the imam as they offer their salah.[44] Two people of the same gender praying in congregation would stand beside each other, with the imam on the left and the other person to his right.[citation needed]

When the worshippers consist of men and women combined, a man leads the prayer. In this situation, women are typically forbidden from assuming this role with unanimous agreement within the major schools of Islam. This is disputed by some, partly based on a hadith with controversial interpretations. When the congregation consists entirely of women and/or pre-pubescent children, a woman may lead the prayer.[45] Some configurations allow for rows of men and women to stand side by side separated by a curtain or other barrier,[46] with the primary intention being for there to be no direct line of sight between male and female worshippers.[47]

Places and times at which salah is prohibited

[edit]Salah is not performed in graveyards and bathrooms. It is prohibited from being performed after Fajr prayer until sunrise, during a small period of time around noon, and after Asr prayer until sunset. The prohibition of salah at these times is to prevent the practice of sun worship.[48]

Obligatory salah

[edit]The daily prayers

[edit]

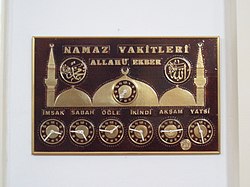

The word salah, when used to refer to the Sunni second pillar of Islam or the Shia ancillary of faith, refers to the five obligatory daily prayers.[49] Each of the five prayers has a prescribed time which depends on the position of the sun in the sky. Given the Islamic day begins at sunset, the first prayer of the day would be Maghrib, performed directly after sunset. It is followed by the Isha salah that is performed during the night, the Fajr salah performed before sunrise, and the Dhuhr and Asr prayers performed in the afternoon.

The five daily prayers must be performed in their prescribed times. However, if extenuating circumstances prevent a Muslim from performing them on time, they must be performed as soon as possible. Several hadith narrations quote the Islamic prophet Muhammad saying that a person who slept past the prescribed time or forgot to perform the obligatory salah must pray it as soon as they remember.[43]

These prayers are considered obligatory upon every adult Muslim,[49] with the exception of those with some physical or mental disabilities,[50] menstruating women, and women experiencing postnatal bleeding.[51] Those who are sick or otherwise physically unable to perform their salah standing may perform them sitting or lying down according to their ability.[52]

Some Muslims pray three times a day, believing the Qur'an mentions three prayers instead of five.[53][54][3]

Friday and Eid prayers

[edit]

In general, Sunnis view the five daily prayers, in addition to the Friday salah, as obligatory. There is a difference of opinion within the Sunni schools of jurisprudence regarding whether the Eid and Witr prayers are obligatory on all Muslims,[55] obligatory only such that a sufficient number of Muslims perform it,[56] or sunnah.[57]

All Sunni schools of jurisprudence view the Friday salah as an obligatory prayer replacing Zuhr on Fridays exclusively. It is obligatory upon men and is to be prayed in congregation, while women have the choice to offer it in congregation or pray Zuhr at home.[58] Preceding the Friday salah, a khutbah (sermon) is delivered by a khatib, after which the 2 rak'a Friday prayer is performed.[59] A minority view within the Sunni schools holds that listening to the khutbah compensates for the spiritual reward of the 2 rak'a that are discounted from the prayer.[60]

The Eid salah is offered on the mornings of Muslim holidays Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. It consists of 2 rak'a, with extra takbirs pronounced before the beginning of the recitation of the Quran in each. The exact number of extra takbirs is differed upon within the Sunni schools, with the majority opining that seven takbirs are pronounced in the first rak'a and five in the second. The Hanafi school holds that 3 takbirs are to be pronounced in each rak'a. After the prayer, a khutbah is delivered. However, unlike the Friday prayer, the khutbah is not an integral part of the Eid prayer.[61] The prescribed time of the Eid prayer is after that of Fajr and before that of Zuhr.[62]

Jam' and Qasr

[edit]Muslims may pray two obligatory prayers together at the prescribed time of one, a practice known as jam'. This is restricted to two pairs of salah: the afternoon prayers of Zuhr and Asr, and the night-time prayers of Maghrib and Isha. Within the schools of jurisprudence in Sunni Islam, there is a difference of opinion regarding the range of reasons that permit one to perform jam'. With the exception of the Hanafi school, the other schools of jurisprudence allow one to perform jam' when travelling or when incapable of performing the prayers separately. Hanbalis and members of the Salafi movement allow jam' for a wider range of reasons.[63][64] Some Salafis ascribing to the Ahl-i Hadith movement also permit jam' without reason while preferring that the prayers be performed separately.[65][66] The Shia Ja'fari school allows one to perform jam' without reason.[67] Exclusively when traveling, a Muslim may shorten the Zuhr, Asr, and Isha prayers, which normally consist of 4 rak'a, to two. This is known as qasr.[62]

Supererogatory salah

[edit]Muslims may perform supererogatory salah as an act of worship at any time except the times of prohibition. Such salah is called nafil .[68] Prayers performed by Muhammad consistently, or those that he recommended be performed but are not considered obligatory, are called sunnah prayers.

Sunan ar-Rawatib

[edit]Sunan ar-Rawatib (Arabic: السنن الرواتب, romanized: as-Sunan ar-Rawātib) refers to the regular voluntary (Sunnah) prayers that are associated with the five daily obligatory (Fard) prayers. These prayers are highly recommended and were regularly practiced by the Islamic Prophet Muhammad. Performing them brings great reward and helps to make up for any deficiencies in the obligatory prayers. They are performed by Sunni Muslims during the prescribed times of the five daily obligatory prayers, either before performing the obligatory prayer or after it. Within the Sunni schools of jurisprudence, these amount to 10 or 12 rak'a, spread between the five prayers except Asr. The Sunan ar-Rawatib performed before the obligatory prayers are performed between the adhan and iqama of their associated salah, while those performed after the obligatory prayer may be performed up to the end of the prescribed time of the associated salah.[citation needed]

The Sunan ar-Rawatib are classified into two categories:[citation needed]

1. Sunnah Mu'akkadah (Emphasized Sunnah): These are the prayers that the Islamic prophet Muhammad regularly performed and strongly encouraged, making them highly recommended.

2. Sunnah Ghair Mu'akkadah (Non-emphasized Sunnah): These prayers were sometimes performed by the Islamic prophet Muhammad but not as consistently, and they are not as strongly emphasized.

Number and Timing of Sunan ar-Rawatib[citation needed]

According to most scholars, there are 12 units (rak'ahs) of Sunnah Mu'akkadah in total, associated with the five daily prayers. These are broken down as follows:

Sunnah Mu'akkadah (Emphasized)[citation needed]

– 2 Rak'ahs before Fajr The Prophet never missed these two rak'ahs, even while traveling.

– 4 Rak'ahs before Dhuhr (prayed in sets of 2) Strongly recommended to pray these 4 rak'ahs before the Dhuhr prayer.

– 2 Rak'ahs after Dhuhr Prayed immediately after the obligatory Dhuhr prayer.

– 2 Rak'ahs after Maghrib Prayed after the Maghrib prayer.

– 2 Rak'ahs after Isha Prayed after the Isha prayer.

Additional Sunnah Ghair Mu'akkadah (Non-emphasized)[citation needed]

Some additional Sunnah prayers, which the Islamic prophet Muhammad occasionally prayed but not consistently, include:

– 2 or 4 Rak'ahs before Asr

– 2 Rak'ahs before Maghrib

– 2 Rak'ahs before Isha

These are not emphasized as strongly as the Sunnah Mu'akkadah but are still meritorious to perform.

Importance and Benefits[citation needed]

Performing the Sunan ar-Rawatib offers several benefits:

– It helps to compensate for any shortcomings or deficiencies in the obligatory prayers.

– It brings great reward and draws a person closer to Allah.

– Muhammad promised that whoever regularly performs these 12 rak'ahs will have a house built in Paradise (Sahih Muslim).

In conclusion, the Sunan ar-Rawatib are a valuable part of a Muslim's daily worship routine, supplementing the obligatory prayers and enhancing one's connection to Allah.

Salah before noon

[edit]Duha salah is a prayer that can be performed after sunrise until noon. (which the time for the Dhuhr Prayer begins) It consists of an even number of rak'a, starting from two and going up to twelve. This prayer is one of 4 sunnah prayers which can be done in congregation.

Salah during the night

[edit]Witr salah (Arabic: صلاة الوتر) is a short prayer generally performed as the last prayer of the night. It consists of an odd number of rak'a, starting from one and going up to eleven, with slight differences between the different schools of jurisprudence.[69] Witr salah often includes the qunut.[70] Within Sunni schools of jurisprudence, the Hanafis view that the Witr salah is obligatory, while the other schools consider it a sunnah salah.

Within Sunni schools of jurisprudence, Tahajjud (Arabic: تَهَجُّد) refers to night-time prayers generally performed after midnight. The prayer includes any number of even rak'a, performed as individual prayers of two rak'a or four. Tahajjud is generally concluded with Witr salah.[69] Shia Muslims offer similar prayers, called Salawat al-Layl (Arabic: صَلَوَات اللَّيل). These are considered highly meritorious, consist of 11 rak'a: 8 nafl (performed as 4 prayers of 2 rak'a each) followed by 3 witr,[71] and can be offered in the same time as Tahajjud.[70]

Tarawih salah (Arabic: صلاة التراويح) is a sunnah prayer performed exclusively during Ramadan by Sunnis. It is performed immediately after the Isha prayer, and consists of 8 to 36 rak'a. Shi'ites hold that Tarawih is a bid'ah initiated by the second Rashidun caliph, Umar. Tarawih is also generally concluded with Witr salah.

Eclipse prayers

[edit]Following the sunnah of Muhammad during the solar eclipse that followed his son Ibrahim's death, Sunni Muslims perform the solar eclipse prayer (Arabic: صلاة الكسوف, romanized: Ṣalāt al-Kusuf), and the lunar eclipse prayer (Arabic: صلاة الخسوف, romanized: Ṣalāt al-Khusuf) during solar and lunar eclipses, respectively. These consist of 2 rak'a with 2 ruku in each rak'a instead of one. It is recommended to lengthen the recitation of the Quran, the bowing, and prostration in these prayers.[citation needed]

Istikhara salah

[edit]The word istikharah is derived from the root ḵ-y-r (خير) "well-being, goodness, choice, selection".[72] Salat al-Istikhaarah is a prayer offered when a Muslim needs guidance on a particular matter. To say this salah one should pray two rakats of non-obligatory salah to completion. After completion one should request Allah that which on is better.[62] The intention for the salah should be in one's heart to pray two rakats of salah followed by Istikhaarah. The salah can be offered at any of the times where salah is not forbidden.[73] Other prayers include the tahiyyat al-masjid, which Muslims are encouraged to offer these two rakat.[74]

Differences in practice

[edit]

While most Muslims pray five times a day, some Muslims pray three times a day, believing the Qur'an only mentions three prayers.[53][54] Qur'anists are among those who pray three times a day.[75]

Most Muslims believe that Muhammad practiced, taught, and disseminated the salah in the whole community of Muslims and made it part of their life. The practice has, therefore, been concurrently and perpetually practiced by the community in each of the generations. The authority for the basic forms of the salah is neither the hadiths nor the Quran, but rather the consensus of Muslims.[76][77]

This is not inconsistent with another fact that Muslims have shown diversity in their practice since the earliest days of practice, so the salah practiced by one Muslim may differ from another's in minor details. In some cases the hadith suggest some of this diversity of practice was known of and approved by Muhammad himself.[78]

Most differences arise because of different interpretations of the Islamic legal sources by the different schools of law (madhhabs) in Sunni Islam, and by different legal traditions within Shia Islam. In the case of ritual worship these differences are generally minor, and should rarely cause dispute.[79]

Common differences, which may vary between schools and gender, include the position of legs, feet, hands and fingers, where the eyes should focus, the minimum amount of recitation, the volume of recitation, and which of the principal elements of the prayer are indispensable, versus recommended or optional.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Na, Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im; Naʻīm, ʻabd Allāh Aḥmad (30 June 2009). Islam and the Secular State. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674033764.

- ^ Edward E. Curtis IV (1 October 2009). Muslims in America: A Short History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974567-8.

- ^ a b Jafarli, Durdana. "The historical conditions for the emergence of the Quranist movement in Egypt in the 19th-20th centuries." МОВА І КУЛЬТУРА (2017): 91.

- ^ Mubarakpuri, Safiur Rahman (1976). Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum [The Sealed Nectar] (PDF) (in Arabic). Translated by Diab, Issam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Chittick, William C.; Murata, Sachiko (1994). The vision of Islam. Paragon House. ISBN 9781557785169.

- ^ "Quran The Final Testament, translated by Rashad Khalifa, Ph.D." www.masjidtucson.org. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Last Name, First Name (2020). "Title". Scientific Route. doi:10.21303/978-617-7319-30-5.

- ^ "British Library".

- ^ Dukes, Kais, ed. (2009–2017). "Quran Dictionary". Quranic Arabic Corpus. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Gerrans, S., "The Quran: A Complete Revelation", 2016

- ^ Vikør 2014.

- ^ Schneider 2014.

- ^ "According to the Bishair the fardh, is like the wajib but the wajib expresses [that something should] occur and the fard, expresses [that something has] a definitive assessment. https://brill.com/display/book/edcoll/9789047400851/B9789047400851_s012.xml?language=en Archived 6 April 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zum Beispiel Sayyid Ahmad Khan. Vgl. Ahmad: Islamic Modernism in India and Pakistan 1857–1964. 1967, S. 49.

- ^ "Ek 15 – Dini Görevler: Tanrı'dan Bir Armağan". Teslimolanlar. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Vgl. Birışık: "Kurʾâniyyûn" in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. 2002, Bd. 26, S. 429.; Yüksel; al-Shaiban; Schulte-Nafeh: Quran: A Reformist Translation. 2007, S. 507.

- ^ "10. How Can we Observe the Sala Prayers by Following the Quran Alone? - Edip-Layth - quranix.org". quranix.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Sahih al-Bukhari 1399, 1400 - Obligatory Charity Tax (Zakat) - كتاب الزكاة - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ "Do all the Imams Agree Neglecting the prayer Continuously Entails Disbelief? (Important Clarification)". Darul Iftaa. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2024.

- ^ Eki̇Nci̇, Ahmet (2021). "İslam Hukukunda Namaz Kılmayanın Hükmü". Kocatepe İslami İlimler Dergisi. 4 (2): 388–409. doi:10.52637/kiid.982657.

- ^ Peters, Rudolph; Vries, Gert J. J. De (1976). "Apostasy in Islam". Die Welt des Islams. 17 (1/4): 7–9. doi:10.2307/1570336. JSTOR 1570336.

- ^ Calder 2009.

- ^ Ziadeh 2009c.

- ^ Sheihul Mufliheen (October 2012). Holy Quran's Judgement. XLIBRIS. p. 57. ISBN 978-1479724550.

- ^ Elias, Abu Amina (25 June 2015). "The purpose of prayer in Islam | Faith in Allah الإيمان بالله". Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ BIN SAAD, ADEL (January 2016). A COMPREHENSIVE DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPHET'S WAY OF PRAYER: صفة صلاة النبي. Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah دار الكتب العلمية. ISBN 978-2745167804.

- ^ "An Enlightening Commentary into the Light of the Holy Qur'an vol. 11". Imam Ali Foundation. 24 January 2014.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. "Salat". oxfordislamicstudies. Archived from the original on 1 September 2009.

- ^ "salat | Definition & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Sahih Muslim 428 - The Book of Prayers - كتاب الصلاة - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck; Smith, Jane I. (1 January 2014). The Oxford Handbook of American Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780199862634.

- ^ Katz, Marion Holmes (6 May 2013). Prayer in Islamic Thought and Practice. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-88788-5.

- ^ Ciaravino, Helene (2001). How to Pray: Tapping into the Power of Divine Communication. Square One Publishers (2001). p. 137. ISBN 9780757000126.

- ^ Al-Tusi, Muhammad Ibn Hasan (2008). Concise Description of Islamic Law and Legal Opinions. Islamic College for Advanced Studie; UK ed. edition (1 October 2008). pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-1904063292.

- ^ Abd al-Wahhab (2019, p. 197)

- ^ al-Albani (2004, p. 108)

- ^ Du'a before Taslim (Sunni View)

- ^ About the Taslim

- ^ "Sahih Muslim 672a - The Book of Mosques and Places of Prayer - كتاب الْمَسَاجِدِ وَمَوَاضِعِ الصَّلاَةِ - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ "The Prostration of Forgetfulness : Shaikh 'Abdullaah bin Saalih Al-'Ubaylaan". muslimlifepro.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ Qara ati, Muhsin (18 February 2018). The Radiance of the Secrets of Prayer. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1496053961.

- ^ "Rules of Salat (Part III of III)". Al-Islam.org. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ a b Qara'ati, Muhsin (5 January 2017). "The Radiance of the Secrets of Prayer". Ahlul Bayt World Assembly.

- ^ Hussain, Musharraf (10 October 2012). The Five Pillars of Islam: Laying the Foundations of Divine Love and Service to Humanity. Kube Publishing Ltd (10 October 2012). pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-1847740540.

- ^ "Iranian women to lead prayers". BBC. 1 August 2000. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J. (2007). Voices of Islam: Voices of life : family, home, and society. Praeger Publishers; 1st edition (1 January 2007). pp. 25–28. ISBN 978-0275987350.

- ^ Maghniyyah, Muhammad Jawad (21 November 2016). "Prayer (Salat), According to the Five Islamic Schools of Law". Islamic Culture and Relations Organisation.

- ^ Ringwald, Christopher D (20 November 2008). A Day Apart: How Jews, Christians, and Muslims Find Faith, Freedom, and Joy on the Sabbath. Oxford University Press (8 January 2007). pp. 117–119. ISBN 978-0195165364.

- ^ a b "Salah (Prayer) – The Second Pillar of Islam". Islamic Relief UK. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Elshabrawy, Elsayed; Hassanein, Ahmad (3 February 2015). Inclusion, Disability and Culture (Studies in Inclusive Education). Sense Publishers (28 November 2014). pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-9462099227.

- ^ GhaneaBassiri, Kambiz (1997). Competing Visions of Islam in the United States: A Study of Los Angeles. Praeger (30 July 1997). ISBN 9780313299513.

- ^ Turner, Colin (19 December 2013). Islam: The Basics. Routledge; 2nd edition (24 May 2011). pp. 106–108. ISBN 978-0415584920.

- ^ a b Na, Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im; Naʻīm, ʻabd Allāh Aḥmad (30 June 2009). Islam and the Secular State. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674033764.

- ^ a b Curtis Iv, Edward E. (October 2009). Muslims in America: A Short History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974567-8.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. "Fard al-Ayn". oxfordislamicstudies. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. "Fard al-Kifayah". oxfordislamicstudies. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010.

- ^ Schade, Johannes (2006). Encyclopedia of World Religions. Mars Media/Foreign Media (9 January 2007). ISBN 978-1601360007.

- ^ Fahd Salem Bahammam. The Muslim's Prayer. Modern Guide. ISBN 9781909322950. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Akhtar Rizvi, Sayyid Saeed (1989). Elements of Islamic Studies. Bilal Muslim Mission of Tanzania.

- ^ Margoliouth, G. (2003). "Sabbath (Muhammadan)". In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 20. Selbie, John A., contrib. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 893–894. ISBN 978-0-7661-3698-4.

- ^ "Islam Today". Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- ^ a b c Buyukcelebi, Ismail (2005). Living in the Shade of Islam. Tughra (1 March 2005). ISBN 978-1932099867.

- ^ "Combining two prayers". Islamweb.net. 16 January 2018. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020.

- ^ Nasir al-Din al-Albani, Muhammad (10 September 2014). "A resident may combine prayers to avoid difficulties – Shaykh al Albaani". Abdurrahman.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017.

- ^ Silmi, Shaykh Yahya. "THE WEAKNESS ABOUT THE NARRATION "COMBINING THE PRAYER WITHOUT REASON IS A MAJOR SIN" AND AN ADVICE TO BROTHER ABU KHADEEJA ABDUL WAHID". Uthman Ibn Affan Library. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021.

- ^ Abu Hibban; Abu Khuzaimah Ansari (15 July 2015). "When To Combine And Shorten Prayers". Salafi Research Institute. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020.

- ^ Sharaf al-Din al-Musawi, Sayyid Abd al-Husayn (18 October 2012). "Combining The Two Prayers". Hydery Canada Ltd.

- ^ "prayers". islamicsupremecouncil.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ a b Islam International Publications (January 2016). Salat: The Muslim prayer book. Islam International Publishers (1997). ISBN 978-1853725463.

- ^ a b Majlisi, Muhammad Baqir (18 November 2021). "Salat al-Layl". Al-Fath Al-Mubin Publications.

- ^ Kassamali, Tahera; Kassamali, Hasnain (9 January 2013). "Salatul Layl". Tayyiba Publishers & Distributors.

- ^ Nieuwkerk, Karin van (October 2013). Performing Piety: Singers and Actors in Egypt's Islamic Revival. University of Texas Press; Reprint edition (1 October 2013). ISBN 9780292745865.

- ^ Iṣlāhī, Muḥammad Yūsuf (1989). "Etiquettes of Life in Islam".

- ^ Firdaus Mediapro, Jannah (17 October 2019). The Path to Islamic Prayer English Edition Standard Version. Blurb (18 October 2019). ISBN 978-1714100736.

- ^ Jafarli, Durdana. "The historical conditions for the emergence of the Quranist movement in Egypt in the 19th–20th centuries." МОВА І КУЛЬТУРА (2017): 91.

- ^ "Al-Mawrid". al-mawrid.org. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- ^ "Mishkat al-Masabih 981 – Prayer – كتاب الصلاة – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Muhammad al-Bukhari. "Sahih al-Bukhari, Book of military expeditions". Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Abdal Hakim Murad. "Understanding the Four Madhhabs". Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abd al-Wahhab, Muhammad ibn (2019). Syarah Adab Berjalan Menuju Shalat [Manners of Walking to the Prayer]. Darul Falah. p. 197. ISBN 9789793036892. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- al-Albani, Muhammad Nasiruddin (2004). Fikih Syekh Albani (in Indonesian). Translated by Mahmud bin Ahmad Rasyid ·. Pustaka Azzam. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Nur Baits, Ammi (2021). Tafsir Shalat. Muamalah Publishing. p. 248 Hadith Riwayat Muslim 1336. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Smith, Jane I.; Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck (1993). The Oxford Handbook of American Islam (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 162–163.

External links

[edit]Salah

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Etymology

The word salāh (صَلَاة), denoting the Islamic ritual prayer, derives from the Arabic triliteral root ṣ-l-w (ص-ل-و), which conveys notions of connection, linking, or adherence, evolving to signify formal prayer as a means of spiritual bonding. The origin of the term is debated among scholars: some consider it a native Arabic development, while others propose it as a loanword from Aramaic ṣlūṯā (ܨܠܘܬܐ), meaning "prayer," borrowed through pre-Islamic Jewish communities in Arabia.[6] This root traces back to pre-Islamic Arabian contexts, where it was employed by monotheistic communities, particularly Jewish groups in the Hijaz, who used analogous terms for liturgical practices borrowed from Aramaic traditions.[7] Within the Semitic language family, salāh shares etymological ties with Aramaic ṣlūṯā (ܨܠܘܬܐ) or slōṭā (צלותא), meaning "prayer" and stemming from the root ś-l-ʾ (to bow, bend, or prostrate), reflecting a common ancestral vocabulary for acts of devotion across Aramaic, Hebrew, and Arabic branches.[8] In Hebrew, while tefillāh (תְּפִלָּה) arises from a distinct root p-l-l (to intercede or judge), it parallels salāh as a structured form of supplication, underscoring broader Semitic conceptual links in ritual worship.[7] The term's evolution is evident in early Islamic texts, where it first appears in the Quran in Surah Al-Baqarah (2:3), describing believers who "establish prayer" (yuqīmūna al-ṣalāh) alongside faith in the unseen, marking its integration as a core religious concept distinct from informal supplication (duʿāʾ). This usage, repeated throughout the Quranic corpus, solidified salāh as a prescribed ritual by the time of the Prophet Muhammad, adapting pre-existing Semitic prayer terminology to the Islamic framework.[9]Related Terms and Names

The Arabic term ṣalāh, denoting the ritual prayer in Islam, is commonly transliterated as salah or salat in English academic and scholarly contexts. In Persian, Turkish, and Urdu linguistic traditions, the equivalent term namaz is widely used, reflecting historical Persian influences on Islamic terminology in non-Arabic regions; namaz derives from Middle Persian namāz, ultimately from Indo-Iranian roots meaning to bow or reverence.[10][11][12] In South Asian Muslim communities, particularly in Pakistan and India, both salat and namaz coexist, with namaz often preferred in everyday vernacular speech due to Urdu and Persian heritage.[11] Salah and salat derive from the Arabic root s-l-w, while namaz has a distinct Persian etymology. Associated vocabulary includes fard, which specifies the obligatory components of prayer; sunnah, referring to the recommended prayers emulating the Prophet Muhammad's practice; and witr, designating the odd-numbered prayer typically performed after the night prayer.[13][14] Regional variations underscore these linguistic adaptations: salah or salat prevails among Arabic-speaking populations in the Middle East, while namaz dominates in non-Arab Muslim societies, including Iran, Turkey, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.[11]Theological Foundations

Quranic Basis

The Quran establishes salah (ritual prayer) as a fundamental obligation for believers, commanding its performance as a means of devotion and connection to God. The term salah and its derivatives appear 99 times in the Quran, underscoring its centrality to Islamic practice.[15] These references often emphasize establishment (iqamah al-salah), portraying it as an act of steadfast worship that integrates physical, spiritual, and communal dimensions. Several verses explicitly mandate the establishment of salah. In Surah Al-Baqarah (2:43), God instructs: "And establish prayer and give zakah and bow with those who bow [in worship and obedience]."[16] This command highlights salah as a collective rite, paired with bowing in submission. Similarly, Surah Al-Baqarah (2:110) states: "Establish prayer and give zakah. Whatever good you put forward for yourselves—you will find it with Allah. Indeed, Allah of what you do, is Seeing," linking salah to righteous deeds rewarded in the hereafter.[17] Another key directive appears in Surah Al-Baqarah (2:238): "Maintain with care the [obligatory] prayers and [in particular] the middle prayer and stand before Allah, devoutly obedient," stressing vigilance in observing all prayers, with special attention to the central one.[18] The Quran also addresses the timing and permanence of salah. Surah An-Nisa (4:103) declares: "When you have finished the prayer, remember Allah standing, sitting, or [lying] on your sides. But when you become secure, re-establish [regular] prayer. Indeed, prayer has been decreed upon the believers a decree of specified times," affirming salah as a timed obligation, even adaptable in times of fear but to be fully reinstated in safety.[19] Regarding its spiritual fruits, Surah Al-Mu'minun (23:1-2) opens: "Certainly will the believers have succeeded: They who are during their prayer humbly submissive," associating success (falah) with humble devotion in salah.[20] Thematically, the Quran portrays salah as intrinsically linked to purification (taharah)—both ritual and moral—and remembrance of God (dhikr). Surah Al-Ankabut (29:45) explains: "Recite what has been revealed to you of the Book and establish prayer. Indeed, prayer prohibits immorality and wrongdoing, and the remembrance of Allah is greater," illustrating salah's role in deterring sin while elevating dhikr as paramount. This purifying effect is echoed in Surah Al-A'la (87:14-15): "Successful indeed are those who purify themselves, remember the Name of their Lord, and pray," where success stems from self-purification sustained through dhikr and salah. Such linkages position salah as a pillar fostering inner and outer cleanliness.[21] Throughout the Quran, salah is frequently coupled with zakat (alms-tax), appearing together in at least 27 verses, which reinforces their complementary roles in spiritual and social purification.[22] This pairing, as in the examples from Surah Al-Baqarah above, underscores salah's obligation alongside acts of charity, forming core expressions of faith.Hadith and Prophetic Tradition

In Islamic tradition, the practice of salah is extensively detailed and authenticated through hadith, which record the sayings, actions, and approvals of the Prophet Muhammad, serving as a practical elaboration on the Quran's commandments to establish prayer. These narrations provide essential guidance on the performance, timing, and spiritual dimensions of salah, ensuring adherence to the Prophetic example (sunnah). For instance, hadith expound upon Quranic injunctions such as "Establish prayer and give zakah" (Quran 2:43) by specifying procedural elements. Major collections of authentic hadith (sahih) form the primary sources for salah-related traditions. Sahih al-Bukhari, compiled by Imam Muhammad al-Bukhari (d. 870 CE), dedicates its eighth book to the times of the prayers, containing narrations that outline the optimal periods for each of the five daily salah based on the Prophet's observations of natural signs like the sun's position. Similarly, Sahih Muslim, assembled by Imam Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj (d. 875 CE), includes extensive sections on prayer postures and etiquettes in its Book of Prayers, such as traditions describing the Prophet's method of standing, reciting, and transitioning between positions to maintain focus and humility. Sunan Abu Dawood, authored by Abu Dawood al-Sijistani (d. 889 CE), further elaborates on ritual purity and prayer obligations in its Kitab al-Salat, offering practical rulings derived from Prophetic conduct, including variations for travelers and the ill.[23] Prophetic sayings underscore salah's paramount importance and key components. One such tradition states: "The key to Paradise is salah, and the key to salah is wudu (ablution)," highlighting prayer as the gateway to divine reward and its prerequisite of purification.[24] Another emphasizes the role of intention (niyyah), as the Prophet declared: "Actions are (judged) by motives (niyyah), so each man will have what he intended," a principle directly applied to salah where the worshipper's inner resolve distinguishes obligatory from supererogatory acts.[25] A hadith qudsi further illustrates the intimate spiritual dialogue in salah: Allah states regarding the recitation of Surah Al-Fatiha, "I have divided the prayer between Myself and My servant into two halves, and My servant shall have what he has asked for," emphasizing how the worshipper's recitations invoke divine response and acceptance.[26] The authentication of these prayer-related hadith relies on the rigorous science of hadith criticism ('ilm al-hadith), particularly the isnad (chain of narration), which traces each report back to the Prophet through a verifiable sequence of trustworthy transmitters. Scholars scrutinized the reliability, memory, and piety of narrators in the isnad to classify hadith as sahih (authentic), hasan (good), or da'if (weak), ensuring only sound traditions guide salah practice.[27] This methodical approach, developed in the first few centuries of Islam, preserved the Prophetic sunnah's integrity against fabrication or error.Religious Significance

Spiritual and Communal Role

In Islamic theology, Salah serves as a direct conduit between the believer and God, often described as the "mi'raj of the believer," symbolizing an ascension akin to the Prophet Muhammad's night journey where the soul elevates through structured communion with the Divine.[28] This ritual fosters a profound spiritual connection, enabling the individual to transcend worldly distractions and attain nearness to Allah, as emphasized in traditional exegeses where prayer is the foundational act of worship prescribed in the Quran.[29] Central to this experience is khushu, a state of humility and mindfulness that requires full presence of heart and mind during the prayer, purifying the soul from heedlessness and aligning the worshipper's intentions solely with divine remembrance.[30] The Quran underscores Salah's role in moral and spiritual elevation, stating that it prevents immorality and wrongdoing while the remembrance of Allah is greater (Quran 29:45), mandates prayer at appointed times (Quran 4:103), describes true believers as those who consistently perform their prayers (Quran 70:22-23), and instructs seeking help through patience and prayer (Quran 2:153).[31][32][33][34] Prophetic traditions in Hadith further emphasize its supreme importance, describing Salah as one of the five pillars on which Islam is built, the first deed for which a servant will be held accountable on the Day of Resurrection—if sound, he prospers and succeeds; if deficient, he fails and loses—and likening the five daily prayers to bathing five times a day in a river that blots out evil deeds.[35][36][37] On a communal level, Salah reinforces the unity of the ummah (Muslim community) by gathering believers in synchronized worship, transcending social, economic, and ethnic divisions to affirm collective equality before God.[38] The timed observance of prayer instills discipline across society, promoting a shared rhythm that strengthens social cohesion and mutual support, as seen in congregational settings where rows of worshippers stand shoulder-to-shoulder, embodying Islamic principles of brotherhood and solidarity.[39] This practice not only cultivates a sense of belonging but also encourages ethical conduct within the community, as the collective act reinforces accountability to divine and communal standards.[40] Empirical studies highlight Salah's psychological benefits, including stress reduction and enhanced mental focus, attributed to its ritualistic repetition and meditative elements that lower cortisol levels and promote parasympathetic nervous system activity.[41] Research indicates that regular performance correlates with decreased anxiety and improved emotional well-being, particularly through the calming effects of prostration and recitation, offering believers a restorative mechanism amid daily pressures.[42] These outcomes align with traditional views of prayer as a holistic discipline that nurtures inner peace and resilience.[43]Conditions of Validity (Shurut)

In Islamic jurisprudence, the conditions of validity (shurut) for Salah refer to the essential prerequisites that must be met prior to commencing the prayer to ensure its acceptance by Allah. These conditions, agreed upon by major schools of thought with minor variations, encompass requirements related to the worshipper's faith, mental state, physical preparation, orientation, and timing. Failure to fulfill any renders the prayer invalid, emphasizing the discipline and purity central to this pillar of Islam.[44][45] The prayer must be performed within its prescribed time, as the entry of the prayer time is a fundamental prerequisite; Salah outside its designated period is not valid.[44][45] The first condition is adherence to Islam, meaning the performer must be a Muslim, as Salah is an act of worship exclusive to believers affirming the testimony of faith. Non-Muslims' prayers are not valid under Islamic law, though they may engage in similar acts of devotion in their own traditions.[44][45] The worshipper must also possess sanity and discernment, requiring a sound mind free from mental incapacity and, for obligation, having reached puberty—typically marked by physical signs like emission of semen for males or menstruation for females around age 15 if no signs appear. Insane individuals or those in a coma are exempt from performing Salah, while pre-pubescent children are encouraged but not held accountable for omissions.[44][45] Intention (niyyah) is crucial, whereby the worshipper must resolve in the heart to perform a specific obligatory or supererogatory prayer, distinguishing it from other acts; verbal utterance is not required but recommended by some scholars. This internal commitment underscores the sincerity demanded in worship.[44][45] Ritual purity (tahara from hadath) demands freedom from minor impurities (e.g., after urination or sleep) through wudu, which involves washing the face, arms to elbows, wiping the head, and washing feet to ankles in sequence, or from major impurities (e.g., after sexual intercourse or postpartum bleeding) via ghusl, a full-body wash. As an exception, tayammum—striking clean earth and wiping the face and hands—substitutes when water is unavailable, such as for travelers or the ill, provided the intention is present.[44][45] Absence of tangible impurities (najasah) requires that the body, clothing, and prayer area be free from filth like urine, blood, or feces; small amounts may be overlooked if removal is impossible without undue hardship, but purity is prioritized to maintain reverence.[44][45] Coverage of the awrah (satr) mandates concealing private parts: for men, from navel to knees; for women, the entire body except face and hands in the presence of non-mahram men, with stricter coverage recommended during prayer. Transparent or tight garments that fail to properly conceal invalidate the Salah.[44][45] Finally, facing the qibla—the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca—is obligatory, achieved by aligning the body toward it using indicators like the sun's position or a compass; exceptions apply if one is traveling on a mount unable to turn or in dire circumstances like battle, where estimation suffices.[44][45] These conditions collectively foster the spiritual focus of Salah, linking legal fulfillment to its role in drawing closer to the Divine.[45]Prayer Times and Prohibitions

Determining Prayer Times

The five daily prayers in Islam—Fajr, Dhuhr, Asr, Maghrib, and Isha—are determined by specific positions of the sun relative to the horizon, providing defined windows for performance based on astronomical observations.[46] These times vary by location and date due to the Earth's rotation and orbit, calculated using factors such as latitude, longitude, the equation of time, and the sun's declination.[47] Fajr begins at true dawn, when the upper rim of the sun is about 18 degrees below the horizon, marking the spread of horizontal light across the sky, and ends at sunrise.[48] Dhuhr starts immediately after the sun passes its zenith (noon) and continues until the start of Asr.[47] Asr commences in the mid-afternoon, defined by the length of an object's shadow: in the Shafi'i, Maliki, and Hanbali schools, it begins when the shadow equals the object's height (plus the noon shadow length), while the Hanafi school uses twice that length for a later start.[48] Maghrib begins at sunset, when the sun's upper disk disappears below the horizon, and lasts until the start of Isha.[47] Isha starts after the disappearance of twilight—typically when the sun is 17–18 degrees below the horizon, depending on the method—and extends until dawn.[48] Calculations rely on solar geometry, accounting for atmospheric refraction (standardized at 0.833 degrees for sunrise/sunset) and twilight angles that differ by jurisprudential convention, such as 18 degrees for Fajr and Isha in the Muslim World League method or 15 degrees in others.[47] Historically, 19th- and 20th-century Muslims used astronomical tables from observatories like Greenwich for twilight determinations, evolving from manual observations to precise formulas.[48] The Islamic lunar (Hijri) calendar influences this by defining the start of each day at sunset (Maghrib), aligning prayer schedules with the civil twilight cycle rather than midnight, though the times themselves remain solar-based.[49] In modern practice, smartphone apps and online calculators implement these algorithms, often allowing users to select madhhab-specific settings like Hanafi Asr timings, using data from sources such as the U.S. Naval Observatory for accuracy across global locations.[47] For polar regions, where continuous daylight or darkness disrupts normal solar markers (e.g., beyond 66 degrees latitude), scholars recommend estimating times from the nearest location at 45 degrees latitude or dividing the 24-hour period analogously to equatorial cycles to maintain the prayer structure.[50]Prohibited Times and Locations

In Islamic jurisprudence, salah is prohibited during specific times of the day to prevent any resemblance to the sun worship practices of pre-Islamic Arabia. These forbidden periods include: from the break of dawn until the sun rises to the height of a spear above the horizon; when the sun reaches its zenith (directly overhead at noon) until it passes the meridian and begins to decline; and from the moment of sunset until the sun fully disappears below the horizon.[51] This ruling is derived from prophetic hadith, such as the narration in Sahih Muslim where the Prophet Muhammad stated that prayer is forbidden after the 'Asr prayer until the sun sets and after the Fajr prayer until the sun rises, emphasizing the avoidance of idolatrous associations.[52] Similarly, Sahih al-Bukhari records the Prophet's prohibition on praying during sunrise, zenith, and sunset, reinforcing these temporal restrictions within the daily prayer cycle.[53] Certain locations are also deemed unsuitable for performing salah to preserve the prayer's sanctity and purity. The Prophet Muhammad explicitly forbade prayer in seven specific places: garbage dumps (rubbish heaps), slaughterhouses, graveyards, the middle of the road, bathrooms (or bathhouses), camel pens (or resting places for camels), and atop the Ka'bah.[54] These prohibitions extend to any area contaminated by impurities, such as rooftops overlooking places of filth or atop moving animals like camels, as such settings distract from reverence or risk ritual impurity.[55] Exceptions are permitted in cases of necessity, such as during travel or emergencies, where one may pray briefly even in restricted areas after removing impurities if possible.[54] Additionally, women are exempt from performing salah during menstruation (hayd) and postpartum bleeding (nifas), as these states render ritual purification (wudu or ghusl) invalid and the prayer itself prohibited.[56] This exemption is based on hadith narrations, including one from Aisha in Sahih al-Bukhari, where the Prophet instructed that menstruating women neither pray nor fast, but must make up missed fasts afterward without compensating for prayers.[56] The duration of this prohibition aligns with the natural end of bleeding, typically three to ten days for menstruation, ensuring women's spiritual obligations resume only after regaining purity through ghusl.[56]Components of Salah

Physical Postures and Movements

The physical postures and movements of Salah form a structured cycle known as a rak'ah, which is repeated varying numbers of times depending on the prayer. Each rak'ah begins with standing upright in qiyam, where the worshipper positions the feet approximately four inches apart and gazes toward the place of prostration. From qiyam, the worshipper transitions to bowing in ruku', bending at the waist until the hands grasp the knees with fingers spread, keeping the back parallel to the ground and the head aligned with the spine. Rising from ruku' occurs in i'tidal, returning to an upright standing position with hands at the sides. The cycle continues with two prostrations in sujud, where the forehead, nose, palms, knees, and toes touch the ground simultaneously, elbows elevated off the body and away from the sides, belly separated from thighs, and knees spaced apart; between the two sujud, the worshipper sits briefly in jalsa with the right foot upright under the body and the left foot extended flat, hands resting on the thighs. The final sitting posture, tashahhud, mirrors jalsa but extends longer.[57][58] Variations exist between Sunni and Shia practices, particularly in hand positioning during qiyam. In Sunni schools, the right hand is placed over the left at chest level or below the navel, forming a folded position to signify humility. In contrast, Shia jurisprudence rejects folding the arms (takattuf), requiring hands to hang naturally at the sides, viewing arm-folding as an innovation without prophetic basis. Head covering is obligatory for women during all postures to ensure the validity of prayer, as the entire body except the face and hands must be covered, with scholarly consensus affirming that uncovering the head invalidates Salah; for men, covering the head with a cap or turban is recommended as a Sunnah but not required.[57][58][59][60] Adaptations to these postures are permitted for those unable to perform them fully due to illness or disability, prioritizing the obligation to pray while accommodating physical limitations. If standing is impossible, the worshipper may pray seated on the ground, a chair, or even lying on the right side facing the Qiblah; bowing and prostration can then be indicated by inclining the head forward more deeply for ruku' and slightly less for sujud, or by gestures if lying down. In extreme cases, such as complete immobility, eye movements or mental focus suffice as substitutes, ensuring the prayer's integrity. Recitations are synchronized with these postures, such as during standing and bowing.[59][61]Recitations and Intentions

The intention (niyyah) in salah is a silent mental declaration made in the heart, specifying the type of prayer (e.g., fard, sunnah) and the number of rak'ahs to be performed, without verbal utterance.[62] This intention must be formed before the opening takbir and serves as a prerequisite for the validity of the prayer.[63] Central to the recitations is the takbir, "Allahu Akbar" (Allah is the Greatest), which marks the commencement of the prayer and transitions between postures.[64] In each rak'ah, following the standing posture, the worshipper recites Surah Al-Fatihah (The Opening), the first chapter of the Quran, which is obligatory; its omission invalidates the prayer.[65] After Al-Fatihah, an additional surah or a selection of verses from the Quran is recited in the first two rak'ahs, though this is sunnah rather than obligatory.[66] In the sitting posture of the second and final rak'ah (depending on the prayer), the tashahhud is recited, comprising testimony of faith, salutations upon the Prophet Muhammad, and supplications for protection from punishment and disbelief.[23] Recitations vary in audibility: they are pronounced aloud (jahri) in the first two rak'ahs of Fajr, Maghrib, and Isha prayers, while silent (sirri) in Dhuhr, Asr, and the remaining rak'ahs of audible prayers.[67] A notable variation occurs in the Witr prayer, where the qunut supplication—a specific du'a for guidance, forgiveness, and protection—is recited after rising from ruku' in the final rak'ah, typically aloud.[68]Congregational Aspects

Leading and Following Prayer

In congregational salah, the role of the imam (prayer leader) requires specific qualifications to ensure the prayer's integrity and the followers' proper guidance. In the Sunni tradition, the imam must be the most knowledgeable individual in the assembly regarding the Quran and the fiqh of salah, enabling accurate recitation and adherence to ritual rulings.[69] Additionally, the imam must maintain ritual purity through wudu (ablution), as the absence of purity invalidates the leadership and necessitates repetition of the prayer by the imam himself, though the followers' prayer remains valid.[70] For mixed congregations including men and women, the imam must be male to uphold established etiquettes of modesty and order.[71] The ma'mum (followers) must align in straight, even rows behind the imam, with shoulders, heels, and ankles level to symbolize unity and equality in worship, beginning alignment from the imam's position.[72] This setup promotes discipline, as the Prophet Muhammad emphasized straightening the rows to avoid gaps or irregularities that could disrupt the congregation's cohesion.[73] In mixed-gender settings, women form rows exclusively behind the men, preserving spatial separation during the prayer.[74] Followers synchronize all movements—such as standing, bowing, prostrating, and sitting—precisely with the imam, avoiding any preceding or excessive delay that could invalidate their prayer, as the imam's actions define the congregational rhythm.[75] Once the imam begins reciting Al-Fatihah, followers refrain from independent recitations in certain Sunni schools like the Hanafi madhhab, instead listening attentively to the imam's audible or silent delivery to fulfill the prayer's communal essence.[76] To address errors due to forgetfulness, such as omitting a required pillar or adding an extra action, the imam performs sujud sahw (prostration of forgetfulness) either before or after the final salam, depending on the mistake's nature, and the ma'mum follow suit to rectify the collective prayer without interrupting the flow.[77] This mechanism, rooted in prophetic practice, ensures corrections are signaled clearly by the imam, maintaining the prayer's validity for all participants.Places of Congregation

The mosque, known as masjid in Arabic, serves as the ideal location for congregational salah due to its dedicated design facilitating collective worship.[78] Central to its architecture is the mihrab, a semicircular niche in the qibla wall that indicates the direction of Mecca and marks the position from which the imam leads the prayer.[79] The minbar, a raised pulpit adjacent to the mihrab, is used by the imam for delivering sermons, particularly during Friday and Eid prayers.[80] The entire prayer hall is oriented toward the qibla to ensure uniformity in worship, promoting communal unity and focus.[81] While the mosque remains the preferred venue, alternative spaces are permissible for group prayers under specific circumstances. For Eid prayers, it is recommended to perform them in open fields or musalla (designated outdoor areas), following the Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad, who consistently held these prayers in such locations to accommodate large gatherings.[82] Small-scale congregational prayers may also occur in homes, particularly for family members or when access to a mosque is limited, though this yields a lesser reward compared to mosque attendance unless justified by an excuse such as distance or hardship.[83] Historically, the concept of dedicated prayer spaces evolved from the Prophet's Mosque in Medina, established around 622 CE as a simple mud-brick structure with a courtyard that functioned not only for worship but also as a center for community, education, and governance.[78] During the Umayyad and Abbasid periods (7th–9th centuries), expansions introduced more elaborate features like covered prayer halls and minarets, reflecting growing urban needs and architectural influences from Byzantine and Persian traditions.[84] Over centuries, mosques adapted to regional contexts, incorporating diverse styles such as the hypostyle halls of North Africa, domed structures in Ottoman Turkey, and minimalist designs in Southeast Asia, while maintaining core elements like the mihrab and qibla orientation amid modern global variations influenced by local materials and urban planning.[85]Obligatory Prayers

The Five Daily Fard Prayers

The five daily fard (obligatory) prayers, known as salah, form the core pillar of Islamic worship and are incumbent upon every sane Muslim who has reached the age of puberty. These prayers—Fajr, Dhuhr, Asr, Maghrib, and Isha—must be performed at prescribed times, with specific numbers of rak'ahs (units of prayer cycles) and recitation styles, as established by the Prophet Muhammad's Sunnah.[67] Failure to perform them without valid excuse constitutes a major sin, requiring sincere repentance and making up the missed prayers (qada).[86] Fajr is the dawn prayer, consisting of 2 rak'ahs recited audibly.[67] It begins at the first light of dawn and ends just before sunrise.[87] Dhuhr is the midday prayer, comprising 4 rak'ahs recited silently.[67] Its time starts when the sun passes its zenith (when an object's shadow equals its height) and ends when the shadow length equals the object's height plus the zenith shadow length—for example, if the zenith shadow is one unit, Dhuhr concludes when the total shadow reaches two units.[87] Asr is the afternoon prayer, with 4 rak'ahs also recited silently.[67] It begins immediately after Dhuhr ends and preferably concludes before the sun turns yellowish, though it may extend to sunset in cases of necessity.[87] Maghrib is the sunset prayer, made up of 3 rak'ahs, with the first two recited audibly and the third silently.[67] It starts at sunset and ends when the twilight (red glow on the horizon) disappears.[87] Isha is the night prayer, consisting of 4 rak'ahs, with the first two recited audibly and the latter two silently.[67] It begins after twilight fades and ends at midnight, the midpoint between sunset and dawn.[87] If a prayer is missed due to forgetfulness, sleep, or unavoidable circumstances, it must be performed as soon as remembered, without sin attached.[86] For deliberate omission, the majority scholarly view requires making it up alongside repentance, though a minority holds that such prayers are invalid and should be replaced with voluntary ones.[86] During travel, these fard prayers may be shortened (qasr) to 2 rak'ahs each for Dhuhr, Asr, and Isha, except for Fajr and Maghrib which remain unchanged.[88]Jumu'ah and Eid Prayers

Jumu'ah prayer, or Salat al-Jumu'ah, is the obligatory congregational prayer performed every Friday at the time of Dhuhr, replacing the four-rak'ah Dhuhr prayer for those who attend. It consists of two rak'ahs led by an imam following two consecutive sermons known as khutbah, during which listeners must remain silent. The Quran commands believers to respond to the call for this prayer by hastening to the remembrance of Allah and ceasing business activities, underscoring its communal significance.[89] Attendance is obligatory for every free, adult Muslim male who is resident and not traveling, as established by prophetic tradition, while women are exempt and may perform the four-rak'ah Dhuhr prayer at home instead. Eid prayers, performed on the occasions of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, are special two-rak'ah congregational prayers that mark the end of Ramadan fasting and the completion of the Hajj pilgrimage with sacrifice, respectively.[90] Each consists of the standard Takbiratul Ihram followed by additional takbirs—typically seven in the first rak'ah and five in the second—recited aloud before the Quranic recitation, distinguishing them from regular prayers.[90] These prayers are led by an imam in a large open space or mosque, emphasizing communal unity, and are immediately followed by a khutbah. Scholars differ on their ruling, with the Hanafi school considering them wajib (obligatory) and others viewing them as sunnah mu'akkadah (emphasized sunnah), but they are universally regarded as highly recommended communal obligations for men, with women encouraged but not required to participate.[90] Participants in both Jumu'ah and Eid prayers are required to perform ghusl (ritual bath) and wear clean, preferably best attire, along with applying perfume for men to enhance the festive and reverent atmosphere. For Eid al-Fitr, it is sunnah to eat an odd number of dates before heading to prayer, while for Eid al-Adha, eating is delayed until after the sacrifice and prayer. Muslims recite takbirs en route to the prayer site, fostering a sense of collective celebration and devotion.Qasr and Jam' Practices

Qasr, or shortening of prayers, is a concession granted to travelers in Islam, allowing the four-rak'ah obligatory prayers of Dhuhr, Asr, and Isha to be performed as two rak'ahs each.[91] This applies to journeys covering a minimum distance that varies by school of jurisprudence: approximately 80 kilometers according to the Shafi'i, Maliki, and Hanbali schools, 77 kilometers according to the Hanafi school, and 44 kilometers according to the Ja'fari school.[92][93][94] Fajr remains two rak'ahs and is not shortened, while Maghrib, already three rak'ahs, is unaffected by qasr.[91] The intention to perform qasr must be formed at the commencement of the prayer, and the ruling ceases upon the traveler's intention to reside at the destination for four or more days in the majority view, or longer periods such as fifteen days in the Hanafi school.[95][91] Jam', or combining prayers, permits the performance of Dhuhr with Asr or Maghrib with Isha in a single session to alleviate hardship.[96] This can occur through taqdim, where both prayers are offered at the time of the earlier one (e.g., Dhuhr and Asr at Dhuhr's time), or ta'khir, at the time of the later one (e.g., at Asr's time).[96] Combining is allowable during travel for all schools except the Hanafi, which restricts it, and for non-travelers in cases of rain or illness according to scholarly consensus.[91][97] For rain, the concession typically applies to Maghrib and Isha if the downpour is sufficient to wet clothing and causes undue difficulty, performed consecutively at Maghrib's time.[98] In illness, a person may combine Dhuhr with Asr or Maghrib with Isha at either time if separate performance would exacerbate hardship, as affirmed by the majority of scholars.[99] These practices modify the five daily fard prayers under specific conditions to facilitate observance.[96] When combining, the prayers are performed in sequence without unnecessary delay between them, and the individual must intend the combination from the outset.[96] Upon returning home or ending the qualifying circumstance, standard prayer timings and lengths resume immediately.[95]Voluntary Prayers

Sunnah Mu'akkadah and Nawafil

Sunnah Mu'akkadah, also referred to as the confirmed or emphasized sunnah prayers (Rawatib), consist of voluntary rak'ahs that the Prophet Muhammad performed consistently and urged his followers to observe as a means of completing the obligatory prayers.[100] These prayers are strongly recommended and carry significant spiritual rewards, with the Prophet rarely omitting them even during travel.[100] The total comprises twelve rak'ahs distributed across the five daily prayers as follows:- Two rak'ahs before Fajr.

- Four rak'ahs before Dhuhr and two rak'ahs after.

- Two rak'ahs after Maghrib.

- Two rak'ahs after Isha.[101]

Night and Witr Prayers

Tahajjud, also known as Qiyam al-Layl, is a voluntary night prayer performed after a period of sleep following the Isha prayer and before the Fajr prayer, with the most virtuous time being the last third of the night.[104] It consists of 2 to 8 rak'ahs, typically offered in even-numbered sets of two, as exemplified by the Prophet Muhammad, who performed eight rak'ahs in this manner before concluding with Witr.[105] The prayer emphasizes seclusion, prolonged standing in recitation of the Quran, and deep reflection, fostering spiritual intimacy and devotion during the quiet hours.[104] Witr serves as the concluding prayer of the night, performed as an odd-numbered unit of one or three rak'ahs immediately after Tahajjud or other night prayers, ensuring the night's worship ends on an odd count as encouraged in the Sunnah.[104] It includes the recitation of Du'a al-Qunut, a supplication offered after the ruku' in the final rak'ah, seeking Allah's guidance, forgiveness, and protection from harm.[68] In the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, Witr holds the status of wajib, rendering it obligatory upon Muslims, based on prophetic narrations emphasizing its performance.[106] The benefits of Tahajjud and Witr are highlighted in prophetic traditions, which describe night prayer as a means of attaining divine forgiveness and closeness to God. For instance, during the last third of the night, Allah descends to the lowest heaven, responding to supplications for forgiveness from those who call upon Him, as reported in a hadith narrated by Abu Hurairah.[107] Additionally, the act of prostration in these prayers represents the pinnacle of nearness to the Divine, where supplications are most readily accepted, underscoring their role in spiritual elevation and mercy.Prayers for Specific Occasions

Prayers for specific occasions in Islam encompass voluntary (sunnah) rituals performed in response to natural phenomena, personal dilemmas, or communal hardships, serving as acts of supplication and remembrance of divine power. These prayers are distinct from daily obligatory or habitual voluntary ones, emphasizing humility and reliance on Allah during extraordinary circumstances. They are rooted in prophetic traditions and are recommended to foster spiritual resilience and community solidarity. Salat al-Kusuf, the prayer during a solar eclipse, and Salat al-Khusuf, for a lunar eclipse, each consist of two rak'ahs performed while the eclipse is underway, from its onset until totality or near completion. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) established this practice as a sunnah mu'akkadah (emphasized sunnah), involving prolonged recitations of the Quran in the standing position (qiyam), extended bowings (ruku'), and prostrations (sujud) to invoke awe and reflection on Allah's signs in the heavens. Unlike regular prayers, there is no adhan or iqamah, and it is ideally offered in congregation at a mosque, though it can be performed individually if necessary. The prayer concludes with a sermon (khutbah) reminding believers of the transient nature of worldly events and the importance of charity and repentance. This ritual underscores the Islamic view that eclipses are natural occurrences, not omens, but opportunities for worship.[108][109] Salat al-Istikhara, the prayer for seeking guidance, is a two-rak'ah voluntary prayer followed by a specific supplication (du'a) when facing a significant decision, such as marriage, business, or travel, where options are permissible but outcomes uncertain. Performed at any time except prohibited prayer times, it begins with the intention to seek Allah's direction toward what is best for one's faith, worldly affairs, and hereafter, as taught by the Prophet: "If you are confused about a matter, then pray two rak'ahs and seek guidance from Allah." The du'a explicitly asks Allah to facilitate ease in beneficial choices and avert harm from detrimental ones, often repeated over seven or more days if clarity is not immediate. Guidance may manifest through inner conviction, external signs, or consultations, emphasizing trust in divine wisdom over personal judgment. This prayer highlights Islam's encouragement of proactive effort combined with spiritual surrender.[110][111] Salat al-Istisqa, the communal prayer for rain, is conducted during prolonged droughts to beseech Allah for relief, typically involving two rak'ahs led by an imam in an open field or mosque, without adhan or iqamah. Performed on a day like 'Arafah or Friday, it features extended takbirs and Quranic recitations, followed by a khutbah where participants turn their outer garments inside out as a symbol of humility and reversal of misfortune. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) led such prayers during times of scarcity in Medina, combining it with repentance, charity, and fasting to purify the community. If rain does not come immediately, the prayer may be repeated up to three times. This ritual reinforces collective dependence on divine mercy for sustenance, often accompanied by brief references to congregational unity in supplication.[112][113] Salat al-Khawf, the prayer of fear, is adapted for situations of imminent danger, such as warfare or severe peril, allowing flexibility in form based on the threat's intensity while preserving the essence of obligatory prayers. In moderate fear, the imam leads one group in the first rak'ah while the other stands guard; they then switch for the second rak'ah, completing individually if needed, as exemplified by the Prophet during the Battle of Uhud. For extreme danger, prayers may be shortened to one rak'ah, performed standing, sitting, or even on mounts, facing the qiblah or the enemy as circumstances dictate, without full congregation. This adaptation, detailed in the Quran (4:102), ensures worship continues amid adversity, prioritizing safety and readiness. It applies specifically to combatants or those under direct threat, distinguishing it from standard prayers.[114]Variations in Practice

Sunni Schools of Jurisprudence