Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stem cell factor

View on WikipediaStem cell factor (also known as SCF, KIT-ligand, KL, or steel factor) is a cytokine that binds to the c-KIT receptor (CD117). SCF can exist both as a transmembrane protein and a soluble protein. This cytokine plays an important role in hematopoiesis (formation of blood cells), spermatogenesis, and melanogenesis.

Production

[edit]The gene encoding stem cell factor (SCF) is found on the Sl locus in mice and on chromosome 12q22-12q24 in humans.[5] The soluble and transmembrane forms of the protein are formed by alternative splicing of the same RNA transcript,[6][7]

The soluble form of SCF contains a proteolytic cleavage site in exon 6. Cleavage at this site allows the extracellular portion of the protein to be released. The transmembrane form of SCF is formed by alternative splicing that excludes exon 6 (Figure 1). Both forms of SCF bind to c-KIT and are biologically active.

Soluble and transmembrane SCF is produced by fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Soluble SCF has a molecular weight of 18,5 kDa and forms a dimer. It is detected in normal human blood serum at 3.3 ng/mL.[8]

Role in development

[edit]SCF plays an important role in the hematopoiesis during embryonic development. Sites where hematopoiesis takes place, such as the fetal liver and bone marrow, all express SCF. Mice that do not express SCF die in utero from severe anemia. Mice that do not express the receptor for SCF (c-KIT) also die from anemia.[9] SCF may serve as guidance cues that direct hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to their stem cell niche (the microenvironment in which a stem cell resides), and it plays an important role in HSC maintenance. Non-lethal point mutants on the c-KIT receptor can cause anemia, decreased fertility, and decreased pigmentation.[10]

During development, the presence of the SCF also plays an important role in the localization of melanocytes, cells that produce melanin and control pigmentation. In melanogenesis, melanoblasts migrate from the neural crest to their appropriate locations in the epidermis. Melanoblasts express the KIT receptor, and it is believed that SCF guides these cells to their terminal locations. SCF also regulates survival and proliferation of fully differentiated melanocytes in adults.[11]

In spermatogenesis, c-KIT is expressed in primordial germ cells, spermatogonia, and in primordial oocytes.[12] It is also expressed in the primordial germ cells of females. SCF is expressed along the pathways that the germ cells use to reach their terminal destination in the body. It is also expressed in the final destinations for these cells. Like for melanoblasts, this helps guide the cells to their appropriate locations in the body.[9]

Role in hematopoiesis

[edit]SCF plays a role in the regulation of HSCs in the stem cell niche in the bone marrow. SCF has been shown to increase the survival of HSCs in vitro and contributes to the self-renewal and maintenance of HSCs in-vivo. HSCs at all stages of development express the same levels of the receptor for SCF (c-KIT).[13] The stromal cells that surround HSCs are a component of the stem cell niche, and they release a number of ligands, including SCF.

In the bone marrow, HSCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells are adjacent to stromal cells, such as fibroblasts and osteoblasts (Figure 2). These HSCs remain in the niche by adhering to ECM proteins and to the stromal cells themselves. SCF has been shown to increase adhesion and thus may play a large role in ensuring that HSCs remain in the niche.[9]

A small percentage of HSCs regularly leave the bone marrow to enter circulation and then return to their niche in the bone marrow.[14] It is believed that concentration gradients of SCF, along with the chemokine SDF-1, allow HSCs to find their way back to the niche.[15]

In adult mice, the injection of the ACK2 anti-KIT antibody, which binds to the c-Kit receptor and inactivates it, leads to severe problems in hematopoiesis. It causes a significant decrease in the number HSC and other hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow.[16] This suggests that SCF and c-Kit plays an important role in hematopoietic function in adulthood. SCF also increases the survival of various hematopoietic progenitor cells, such as megakaryocyte progenitors, in vitro.[17] In addition, it works with other cytokines to support the colony growth of BFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM4. Hematopoietic progenitor cells have also been shown to migrate towards a higher concentration gradient of SCF in vitro, which suggests that SCF is involved in chemotaxis for these cells.

Fetal HSCs are more sensitive to SCF than HSCs from adults. In fact, fetal HSCs in cell culture are 6 times more sensitive to SCF than adult HSCs based on the concentration that allows maximum survival.[18]

Expression in mast cells

[edit]Mast cells are the only terminally differentiated hematopoietic cells that express the c-Kit receptor. Mice with SCF or c-Kit mutations have severe defects in the production of mast cells, having less than 1% of the normal levels of mast cells. Conversely, the injection of SCF increases mast cell numbers near the site of injection by over 100 times. In addition, SCF promotes mast cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and survival.[19] It also promotes the release of histamine and tryptase, which are involved in the allergic response.

Soluble and transmembrane forms

[edit]The presence of both soluble and transmembrane SCF is required for normal hematopoietic function.[6][20] Mice that produce the soluble SCF but not transmembrane SCF suffer from anemia, are sterile, and lack pigmentation. This suggests that transmembrane SCF plays a special role in vivo that is separate from that of soluble SCF.

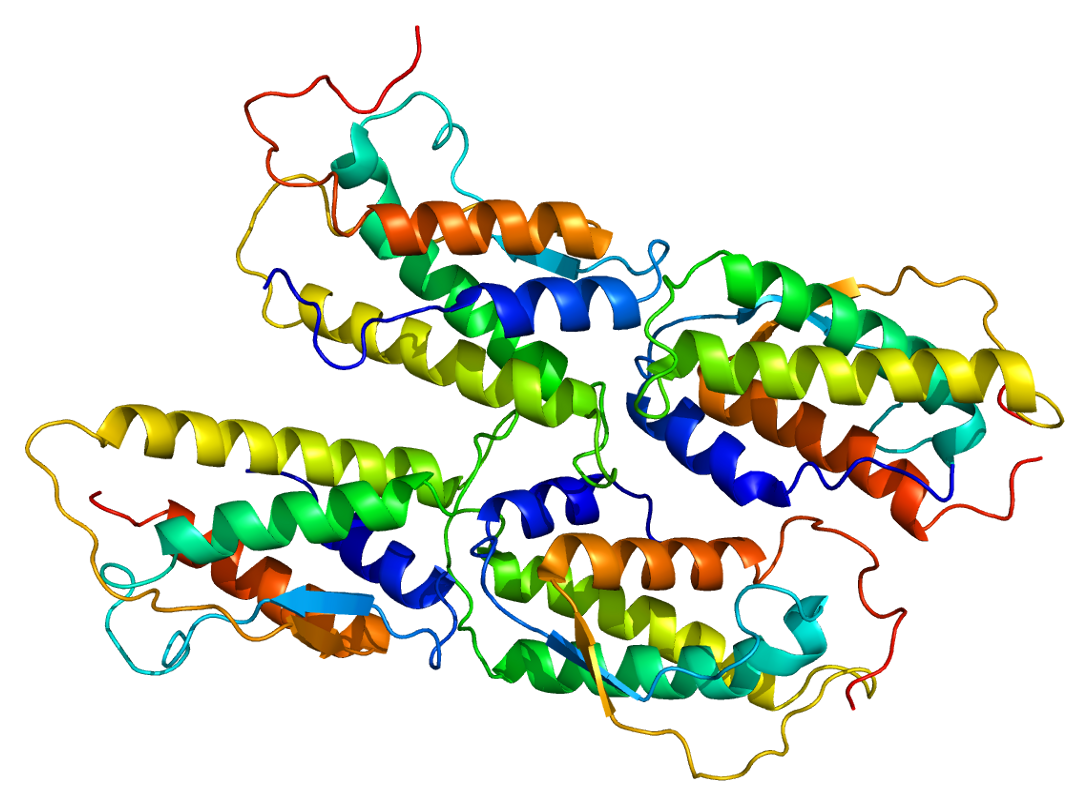

c-KIT receptor

[edit]

SCF binds to the c-KIT receptor (CD 117), a receptor tyrosine kinase.[21] c-Kit is expressed in HSCs, mast cells, melanocytes, and germ cells. It is also expressed in hematopoietic progenitor cells including erythroblasts, myeloblasts, and megakaryocytes. However, with the exception of mast cells, expression decreases as these hematopoietic cells mature and c-KIT is not present when these cells are fully differentiated (Figure 3). SCF binding to c-KIT causes the receptor to homodimerize and auto-phosphorylate at tyrosine residues. The activation of c-Kit leads to the activation of multiple signaling cascades, including the RAS/ERK, PI3-Kinase, Src kinase, and JAK/STAT pathways.[21]

Clinical relevance

[edit]SCF may be used along with other cytokines to culture HSCs and hematopoietic progenitors. The expansion of these cells ex-vivo (outside the body) would allow advances in bone marrow transplantation, in which HSCs are transferred to a patient to re-establish blood formation.[13] One of the problems of injecting SCF for therapeutic purposes is that SCF activates mast cells. The injection of SCF has been shown to cause allergic-like symptoms and the proliferation of mast cells and melanocytes.[9]

Cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of transmembrane SCF promotes stem cell migration and improves cardiac function and animal survival after myocardial infarction.[22]

Interactions

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000049130 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000019966 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Geissler EN, Liao M, Brook JD, Martin FH, Zsebo KM, Housman DE, Galli SJ (March 1991). "Stem cell factor (SCF), a novel hematopoietic growth factor and ligand for c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor, maps on human chromosome 12 between 12q14.3 and 12qter". Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 17 (2): 207–14. doi:10.1007/BF01232978. PMID 1707188. S2CID 37793786.

- ^ a b Flanagan JG, Chan DC, Leder P (March 1991). "Transmembrane form of the kit ligand growth factor is determined by alternative splicing and is missing in the Sld mutant". Cell. 64 (5): 1025–35. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90326-t. PMID 1705866. S2CID 11266238.

- ^ Anderson DM, Williams DE, Tushinski R, Gimpel S, Eisenman J, Cannizzaro LA, Aronson M, Croce CM, Huebner K, Cosman D (August 1991). "Alternate splicing of mRNAs encoding human mast cell growth factor and localization of the gene to chromosome 12q22-q24". Cell Growth Differ. 2 (8): 373–8. PMID 1724381.

- ^ Langley KE, Bennett LG, Wypych J, Yancik SA, Liu XD, Westcott KR, Chang DG, Smith KA, Zsebo KM (February 1993). "Soluble stem cell factor in human serum". Blood. 81 (3): 656–60. doi:10.1182/blood.V81.3.656.656. PMID 7678995.

- ^ a b c d Broudy VC (August 1997). "Stem cell factor and hematopoiesis". Blood. 90 (4): 1345–64. doi:10.1182/blood.V90.4.1345. PMID 9269751.

- ^ Blouin R, Bernstein A (1993). "The White spotting and Steel hereditary anaemias of the mouse". In Freedman MH, Feig SA (eds.). Clinical disorders and experimental models of erythropoietic failure. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-6678-X.

- ^ Wehrle-Haller B (June 2003). "The role of Kit-ligand in melanocyte development and epidermal homeostasis". Pigment Cell Res. 16 (3): 287–96. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00055.x. PMID 12753403.

- ^ Rossi P, Sette C, Dolci S, Geremia R (October 2000). "Role of c-kit in mammalian spermatogenesis" (PDF). J. Endocrinol. Invest. 23 (9): 609–15. doi:10.1007/bf03343784. hdl:2108/65858. PMID 11079457. S2CID 43786244.

- ^ a b Kent D, Copley M, Benz C, Dykstra B, Bowie M, Eaves C (April 2008). "Regulation of hematopoietic stem cells by the steel factor/KIT signaling pathway". Clin. Cancer Res. 14 (7): 1926–30. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5134. PMID 18381929.

- ^ Méndez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS (March 2008). "Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations". Nature. 452 (7186): 442–7. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..442M. doi:10.1038/nature06685. PMID 18256599. S2CID 4403554.

- ^ Nervi B, Link DC, DiPersio JF (October 2006). "Cytokines and hematopoietic stem cell mobilization". J. Cell. Biochem. 99 (3): 690–705. doi:10.1002/jcb.21043. PMID 16888804. S2CID 40354996.

- ^ Ogawa M, Matsuzaki Y, Nishikawa S, Hayashi S, Kunisada T, Sudo T, Kina T, Nakauchi H, Nishikawa S (July 1991). "Expression and function of c-kit in hemopoietic progenitor cells". J. Exp. Med. 174 (1): 63–71. doi:10.1084/jem.174.1.63. PMC 2118893. PMID 1711568.

- ^ Keller JR, Ortiz M, Ruscetti FW (September 1995). "Steel factor (c-kit ligand) promotes the survival of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in the absence of cell division". Blood. 86 (5): 1757–64. doi:10.1182/blood.V86.5.1757.bloodjournal8651757. PMID 7544641.

- ^ Bowie MB, Kent DG, Copley MR, Eaves CJ (June 2007). "Steel factor responsiveness regulates the high self-renewal phenotype of fetal hematopoietic stem cells". Blood. 109 (11): 5043–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-037770. PMID 17327414.

- ^ Okayama Y, Kawakami T (2006). "Development, migration, and survival of mast cells". Immunol. Res. 34 (2): 97–115. doi:10.1385/IR:34:2:97. PMC 1490026. PMID 16760571.

- ^ Brannan CI, Lyman SD, Williams DE, Eisenman J, Anderson DM, Cosman D, Bedell MA, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG (June 1991). "Steel-Dickie mutation encodes a c-kit ligand lacking transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (11): 4671–4. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.4671B. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.11.4671. PMC 51727. PMID 1711207.

- ^ a b Rönnstrand L (October 2004). "Signal transduction via the stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61 (19–20): 2535–48. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4189-6. PMC 11924424. PMID 15526160. S2CID 2602233.

- ^ Xiang FL, Lu X, Hammoud L, Zhu P, Chidiac P, Robbins J, Feng Q (September 2009). "Cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of human stem cell factor improves cardiac function and survival after myocardial infarction in mice". Circulation. 120 (12): 1065–74, 9 p following 1074. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.839068. PMID 19738140.

- ^ Lev S, Yarden Y, Givol D (May 1992). "A recombinant ectodomain of the receptor for the stem cell factor (SCF) retains ligand-induced receptor dimerization and antagonizes SCF-stimulated cellular responses". J. Biol. Chem. 267 (15): 10866–73. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50098-9. PMID 1375232.

- ^ Blechman JM, Lev S, Brizzi MF, Leitner O, Pegoraro L, Givol D, Yarden Y (Feb 1993). "Soluble c-kit proteins and antireceptor monoclonal antibodies confine the binding site of the stem cell factor". J. Biol. Chem. 268 (6): 4399–406. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53623-1. PMID 7680037.

Further reading

[edit]- Lennartsson J, Rönnstrand L (2012). "Stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit: from basic science to clinical implications". Physiol. Rev. 92 (4): 1619–49. doi:10.1152/physrev.00046.2011. PMID 23073628.

- Broudy VC (1997). "Stem cell factor and hematopoiesis". Blood. 90 (4): 1345–64. doi:10.1182/blood.V90.4.1345. PMID 9269751.

- Andrews RG, Briddell RA, Appelbaum FR, McNiece IK (1994). "Stimulation of hematopoiesis in vivo by stem cell factor". Curr. Opin. Hematol. 1 (3): 187–96. PMID 9371281.

- Wehrle-Haller B (2003). "The role of Kit-ligand in melanocyte development and epidermal homeostasis". Pigment Cell Res. 16 (3): 287–96. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00055.x. PMID 12753403.

- Rönnstrand L (2004). "Signal transduction via the stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61 (19–20): 2535–48. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4189-6. PMC 11924424. PMID 15526160. S2CID 2602233.

- Mroczko B, Szmitkowski M (2004). "Hematopoietic cytokines as tumor markers". Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 42 (12): 1347–54. doi:10.1515/CCLM.2004.253. PMID 15576295. S2CID 11414705.

- Lev S, Yarden Y, Givol D (1992). "A recombinant ectodomain of the receptor for the stem cell factor (SCF) retains ligand-induced receptor dimerization and antagonizes SCF-stimulated cellular responses". J. Biol. Chem. 267 (15): 10866–73. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50098-9. PMID 1375232.

- Huang EJ, Nocka KH, Buck J, Besmer P (1992). "Differential expression and processing of two cell associated forms of the kit-ligand: KL-1 and KL-2". Mol. Biol. Cell. 3 (3): 349–62. doi:10.1091/mbc.3.3.349. PMC 275535. PMID 1378327.

- Toyota M, Hinoda Y, Itoh F, Tsujisaki M, Imai K, Yachi A (1992). "Expression of two types of kit ligand mRNAs in human tumor cells". Int. J. Hematol. 55 (3): 301–4. PMID 1379846.

- Lu HS, Clogston CL, Wypych J, Parker VP, Lee TD, Swiderek K, Baltera RF, Patel AC, Chang DC, Brankow DW (1992). "Post-translational processing of membrane-associated recombinant human stem cell factor expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 298 (1): 150–8. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(92)90106-7. PMID 1381905.

- Sharkey A, Jones DS, Brown KD, Smith SK (1992). "Expression of messenger RNA for kit-ligand in human placenta: localization by in situ hybridization and identification of alternatively spliced variants". Mol. Endocrinol. 6 (8): 1235–41. doi:10.1210/mend.6.8.1383693. PMID 1383693.

- Mathew S, Murty VV, Hunziker W, Chaganti RS (1992). "Subregional mapping of 13 single-copy genes on the long arm of chromosome 12 by fluorescence in situ hybridization". Genomics. 14 (3): 775–9. doi:10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80184-3. PMID 1427906.

- Geissler EN, Liao M, Brook JD, Martin FH, Zsebo KM, Housman DE, Galli SJ (1991). "Stem cell factor (SCF), a novel hematopoietic growth factor and ligand for c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor, maps on human chromosome 12 between 12q14.3 and 12qter". Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 17 (2): 207–14. doi:10.1007/BF01232978. PMID 1707188. S2CID 37793786.

- Anderson DM, Williams DE, Tushinski R, Gimpel S, Eisenman J, Cannizzaro LA, Aronson M, Croce CM, Huebner K, Cosman D (1991). "Alternate splicing of mRNAs encoding human mast cell growth factor and localization of the gene to chromosome 12q22-q24". Cell Growth Differ. 2 (8): 373–8. PMID 1724381.

- Martin FH, Suggs SV, Langley KE, Lu HS, Ting J, Okino KH, Morris CF, McNiece IK, Jacobsen FW, Mendiaz EA (1990). "Primary structure and functional expression of rat and human stem cell factor DNAs". Cell. 63 (1): 203–11. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90301-T. PMID 2208279. S2CID 9425857.

- Ramenghi U, Ruggieri L, Dianzani I, Rosso C, Brizzi MF, Camaschella C, Pietsch T, Saglio G (1994). "Human peripheral blood granulocytes and myeloid leukemic cell lines express both transcripts encoding for stem cell factor". Stem Cells. 12 (5): 521–6. doi:10.1002/stem.5530120508. PMID 7528592. S2CID 39550926.

- Saito S, Enomoto M, Sakakura S, Ishii Y, Sudo T, Ichijo M (1994). "Localization of stem cell factor (SCF) and c-kit mRNA in human placental tissue and biological effects of SCF on DNA synthesis in primary cultured cytotrophoblasts". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 205 (3): 1762–9. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1994.2873. PMID 7529021.

- Laitinen M, Rutanen EM, Ritvos O (1995). "Expression of c-kit ligand messenger ribonucleic acids in human ovaries and regulation of their steady state levels by gonadotropins in cultured granulosa-luteal cells". Endocrinology. 136 (10): 4407–14. doi:10.1210/endo.136.10.7545103. PMID 7545103.

- Blechman JM, Lev S, Brizzi MF, Leitner O, Pegoraro L, Givol D, Yarden Y (1993). "Soluble c-kit proteins and antireceptor monoclonal antibodies confine the binding site of the stem cell factor". J. Biol. Chem. 268 (6): 4399–406. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53623-1. PMID 7680037.

- Lu HS, Jones MD, Shieh JH, Mendiaz EA, Feng D, Watler P, Narhi LO, Langley KE (1996). "Isolation and characterization of a disulfide-linked human stem cell factor dimer. Biochemical, biophysical, and biological comparison to the noncovalently held dimer". J. Biol. Chem. 271 (19): 11309–16. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.19.11309. PMID 8626683.

- Vanhaesebroeck B, Welham MJ, Kotani K, Stein R, Warne PH, Zvelebil MJ, Higashi K, Volinia S, Downward J, Waterfield MD (1997). "P110delta, a novel phosphoinositide 3-kinase in leukocytes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (9): 4330–5. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.4330V. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.9.4330. PMC 20722. PMID 9113989.

External links

[edit]- Stem+cell+factor at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- https://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/show_pathway?hsa04640+4254 - KEGG pathway: Hematopoietic cell lineage