Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mast cell

View on Wikipedia

| Mastocyte | |

|---|---|

Mast cell (large dark cell in the center of the field of view) surrounded by bone marrow cells, Giemsa stain, 1000x. | |

| Details | |

| System | Immune system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | mastocytus |

| MeSH | D008407 |

| TH | H2.00.03.0.01010 |

| FMA | 66784 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

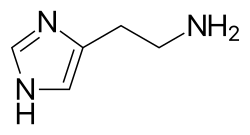

A mast cell (also known as a mastocyte or a labrocyte[1]) is a resident cell of connective tissue that contains many granules rich in histamine and heparin. Specifically, it is a type of granulocyte derived from the myeloid stem cell that is a part of the immune and neuroimmune systems. Mast cells were discovered by Friedrich von Recklinghausen and later rediscovered by Paul Ehrlich in 1877.[2] Although best known for their role in allergy and anaphylaxis, mast cells play an important protective role as well, being intimately involved in wound healing, angiogenesis, immune tolerance, defense against pathogens, and vascular permeability in brain tumors.[3][4]

The mast cell is very similar in both appearance and function to the basophil, another type of white blood cell. Although mast cells were once thought to be tissue-resident basophils, it has been shown that the two cells develop from different hematopoietic lineages and thus cannot be the same cells.[5]

Structure

[edit]

Mast cells are very similar to basophil granulocytes (a class of white blood cells) in blood, in the sense that both are granulated cells that contain histamine and heparin, an anticoagulant. Their nuclei differ in that the basophil nucleus is lobated while the mast cell nucleus is round. The Fc region of immunoglobulin E (IgE) becomes bound to mast cells and basophils, and when IgE's paratopes bind to an antigen, it causes the cells to release histamine and other inflammatory mediators.[6] These similarities have led many to speculate that mast cells are basophils that have "homed in" on tissues. Furthermore, they share a common precursor in bone marrow expressing the CD34 molecule. Basophils leave the bone marrow already mature, whereas the mast cell circulates in an immature form, only maturing once in a tissue site. The site an immature mast cell settles in probably determines its precise characteristics.[7] The first in vitro differentiation and growth of a pure population of mouse mast cells was carried out using conditioned medium derived from concanavalin A-stimulated splenocytes.[8] Later, it was discovered that T cell-derived interleukin 3 was the component present in the conditioned media that was required for mast cell differentiation and growth.[9]

Mast cells in rodents are classically divided into two subtypes: connective tissue-type mast cells and mucosal mast cells. The activities of the latter are dependent on T-cells.[10]

Mast cells are present in most tissues characteristically surrounding blood vessels, nerves and lymphatic vessels,[11] and are especially prominent near the boundaries between the outside world and the internal milieu, such as the skin, mucosa of the lungs, and digestive tract, as well as the mouth, conjunctiva, and nose.[7]

Function

[edit]

Mast cells play a key role in the inflammatory process. When activated, a mast cell can either selectively release (piecemeal degranulation) or rapidly release (anaphylactic degranulation) "mediators", or compounds that induce inflammation, from storage granules into the local microenvironment.[3][12] Mast cells can be stimulated to degranulate by allergens through cross-linking with immunoglobulin E receptors (e.g., FcεRI), physical injury through pattern recognition receptors for damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), microbial pathogens through pattern recognition receptors for pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and various compounds through their associated G-protein coupled receptors (e.g., morphine through opioid receptors) or ligand-gated ion channels.[3][12] Complement proteins can activate membrane receptors on mast cells to exert various functions as well.[7]

Mast cells express a high-affinity receptor (FcεRI) for the Fc region of IgE, the least-abundant member of the antibodies. This receptor is of such high affinity that binding of IgE molecules is in essence irreversible. As a result, mast cells are coated with IgE, which is produced by plasma cells (the antibody-producing cells of the immune system). IgE antibodies are typically specific to one particular antigen.

In allergic reactions, mast cells remain inactive until an allergen binds to IgE already coated upon the cell. Other membrane activation events can either prime mast cells for subsequent degranulation or act in synergy with FcεRI signal transduction.[13] In general, allergens are proteins or polysaccharides. The allergen binds to the antigen-binding sites, which are situated on the variable regions of the IgE molecules bound to the mast cell surface. It appears that binding of two or more IgE molecules (cross-linking) is required to activate the mast cell. The clustering of the intracellular domains of the cell-bound Fc receptors, which are associated with the cross-linked IgE molecules, causes a complex sequence of reactions inside the mast cell that lead to its activation. Although this reaction is most well understood in terms of allergy, it appears to have evolved as a defense system against parasites and bacteria.[14]

Mast cells (MCs) have been shown to release their nuclear DNA and subsequently form mast cell extracellular traps (MCETs) comparable to neutrophil extracellular traps, which are able to entrap and kill various microbes.[15]

Mast cell mediators

[edit]A unique, stimulus-specific set of mast cell mediators is released through degranulation following the activation of cell surface receptors on mast cells.[12] Examples of mediators that are released into the extracellular environment during mast cell degranulation include:[7][12][16]

- serine proteases, such as tryptase and chymase

- histamine (2–5 picograms per mast cell)

- serotonin

- proteoglycans, mainly heparin (active as anticoagulant) and some chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans

- adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

- lysosomal enzymes

- newly formed lipid mediators (eicosanoids):

- cytokines

- reactive oxygen species

Histamine dilates post-capillary venules, activates the endothelium, and increases blood vessel permeability. This leads to local edema (swelling), warmth, redness, and the attraction of other inflammatory cells to the site of release. It also depolarizes nerve endings (leading to itching or pain). Cutaneous signs of histamine release are the "flare and wheal"-reaction. The bump and redness immediately following a mosquito bite are a good example of this reaction, which occurs seconds after challenge of the mast cell by an allergen.[7]

The other physiologic activities of mast cells are much less-understood. Several lines of evidence suggest that mast cells may have a fairly fundamental role in innate immunity: They are capable of elaborating a vast array of important cytokines and other inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α; they express multiple "pattern recognition receptors" thought to be involved in recognizing broad classes of pathogens; and mice without mast cells seem to be much more susceptible to a variety of infections.[citation needed]

Mast cell granules carry a variety of bioactive chemicals. These granules have been found to be transferred to adjacent cells of the immune system and neurons in a process of transgranulation via mast cell pseudopodia.[17]

In the nervous system

[edit]Unlike other hematopoietic cells of the immune system, mast cells naturally occur in the human brain where they interact with the neuroimmune system.[4] In the brain, mast cells are located in a number of structures that mediate visceral sensory (e.g. pain) or neuroendocrine functions or that are located along the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier, including the pituitary stalk, pineal gland, thalamus, and hypothalamus, area postrema, choroid plexus, and in the dural layer of the meninges near meningeal nociceptors.[4] Mast cells serve the same general functions in the body and central nervous system, such as effecting or regulating allergic responses, innate and adaptive immunity, autoimmunity, and inflammation.[4][18] Across systems, mast cells serve as the main effector cell through which pathogens can affect the gut–brain axis.[19][20]

In the gut

[edit]In the gastrointestinal tract, mucosal mast cells are located in close proximity to sensory nerve fibres, which communicate bidirectionally.[21][19][20] When these mast cells initially degranulate, they release mediators (e.g., histamine, tryptase, and serotonin) which activate, sensitize, and upregulate membrane expression of nociceptors (i.e., TRPV1) on visceral afferent neurons via their receptors (respectively, HRH1, HRH2, HRH3, PAR2, 5-HT3);[21] in turn, neurogenic inflammation, visceral hypersensitivity, and intestinal dysmotility (i.e., impaired peristalsis) result.[21] Neuronal activation induces neuropeptide (substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide) signaling to mast cells where they bind to their associated receptors and trigger degranulation of a distinct set of mediators (β-Hexosaminidase, cytokines, chemokines, PGD2, leukotrienes, and eoxins).[21][12]

Physiology

[edit]

Structure of the high-affinity IgE receptor, FcεR1

[edit]FcεR1 is a high affinity IgE-receptor that is expressed on the surface of the mast cell. FcεR1 is a tetramer made of one alpha (α) chain, one beta (β) chain, and two identical, disulfide-linked gamma (γ) chains. The binding site for IgE is formed by the extracellular portion of the α chain that contains two domains that are similar to Ig. One transmembrane domain contains an aspartic acid residue, and one contains a short cytoplasmic tail.[22] The β chain contains, a single immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif ITAM, in the cytoplasmic region. Each γ chain has one ITAM on the cytoplasmic region. The signaling cascade from the receptor is initiated when the ITAMs of the β and γ chains are phosphorylated by a tyrosine kinase. This signal is required for the activation of mast cells.[23] Type 2 helper T cells,(Th2) and many other cell types lack the β chain, so signaling is mediated only by the γ chain. This is due to the α chain containing endoplasmic reticulum retention signals that causes the α-chains to remain degraded in the ER. The assembly of the α chain with the co-transfected β and γ chains mask the ER retention and allows the α β γ complex to be exported to the golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane in rats. In humans, only the γ complex is needed to counterbalance the α chain ER retention.[22]

Allergen process

[edit]Allergen-mediated FcεR1 cross-linking signals are very similar to the signaling event resulting in antigen binding to lymphocytes. The Lyn tyrosine kinase is associated with the cytoplasmic end of the FcεR1 β chain. The antigen cross-links the FcεR1 molecules, and Lyn tyrosine kinase phosphorylates the ITAMs in the FcεR1 β and γ chain in the cytoplasm. Upon the phosphorylation, the Syk tyrosine kinase gets recruited to the ITAMs located on the γ chains. This causes activation of the Syk tyrosine kinase, causing it to phosphorylate.[23] Syk functions as a signal amplifying kinase activity due to the fact that it targets multiple proteins and causes their activation.[24] This antigen stimulated phosphorylation causes the activation of other proteins in the FcεR1-mediated signaling cascade.[25]

Degranulation and fusion

[edit]An important adaptor protein activated by the Syk phosphorylation step is the linker for activation of T cells (LAT). LAT can be modified by phosphorylation to create novel binding sites.[24] Phospholipase C gamma (PLCγ) becomes phosphorylated once bound to LAT, and is then used to catalyze phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate breakdown to yield inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacyglycerol (DAG). IP3 elevates calcium levels, and DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC). This is not the only way that PKC is made. The tyrosine kinase FYN phosphorylates Grb2-associated-binding protein 2 (Gab2), which binds to phosphoinositide 3-kinase, which activates PKC. PKC leads to the activation of myosin light-chain phosphorylation granule movements, which disassembles the actin–myosin complexes to allow granules to come into contact with the plasma membrane.[23] The mast cell granule can now fuse with the plasma membrane. Soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion attachment protein receptor SNARE complex mediates this process. Different SNARE proteins interact to form different complexes that catalyze fusion. Rab3 guanosine triphosphatases and Rab-associated kinases and phosphatases regulate granule membrane fusion in resting mast cells.

MRGPRX2 mast cell receptor

[edit]Human mast-cell-specific G-protein-coupled receptor MRGPRX2 plays a key role in the recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and initiating an antibacterial response. MRGPRX2 is able to bind to competence stimulating peptide (CSP) 1 - a quorum sensing molecule (QSM) produced by Gram-positive bacteria.[26] This leads to signal transduction to a G protein and activation of the mast cell. Mast cell activation induces the release of antibacterial mediators including ROS, TNF-α and PRGD2 which institute the recruitment of other immune cells to inhibit bacterial growth and biofilm formation.

The MRGPRX2 receptor is a possible therapeutic target and can be pharmacologically activated using the agonist compound 48/80 to control bacterial infection.[27] It is also hypothesised that other QSMs and even Gram-negative bacterial signals can activate this receptor. This might particularly be the case during Bartonella chronic infections where it appears clearly in human symptomatology that these patients all have a mast cell activation syndrome due to the presence of a not yet defined quorum sensing molecule (basal histamine itself?). Those patients are prone to food intolerance driven by another less specific path than the IgE receptor path: certainly the MRGPRX2 route. These patients also show cyclical skin pathergy and dermographism, every time the bacteria exits its hidden intracellular location.

Enzymes

[edit]| Enzyme | Function |

|---|---|

| Lyn tyrosine kinase | Phosphorylates the ITAMs in the FcεR1 β and γ chain in the cytoplasm. It causes Syk tyrosine kinase to get recruited to the ITAMS located on the γ chains. This causes activation of the Syk tyrosine kinase, causing it to phosphorylate |

| Syk tyrosine kinase | Targets multiple proteins and causes their activation |

| Phospholipase C | Catalyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate |

| Inositol trisphosphate | Elevates calcium levels |

| Diacylglycerol | Activates protein kinase C |

| FYN | Phosphorylates GAB2 |

| GAB2 | Binds to phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| Phosphoinositide 3-kinase | Activates protein kinase C |

| Protein kinase C | Activates myosin light-chain phosphorylation granule movements that disassemble the actin-myosin complexes |

| Rab-associated kinases and phosphatases | Regulate cell granule membrane fusion in resting mast cells |

Clinical significance

[edit]Parasitic infections

[edit]Mast cells are activated in response to infection by pathogenic parasites, such as certain helminths and protozoa, through IgE signaling.[28] Various species known to be affected include T.spiralis, S.ratti, and S.venezuelensis.[28] This is accomplished via Type 2 cell-mediated effector immunity, which is characterized by signaling from IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13.[28][29] It is the same immune response that is responsible for allergic inflammation more generally, and includes effectors beyond mast cells.[28][29] In this response, mast cells are known to release significant quantities of IL-4 and IL-13 along with mast cell chymase 1 (CMA1), which is considered to help expel some worms by increasing vascular permeability.[28]

Mast cell activation disorders

[edit]Mast cell activation disorders (MCAD) are a spectrum of immune disorders that are unrelated to pathogenic infection and involve similar symptoms that arise from secreted mast cell intermediates, but differ slightly in their pathophysiology, treatment approach, and distinguishing symptoms.[30][31] The classification of mast cell activation disorders was laid out in 2010.[30][31]

Allergic disease

[edit]Allergies are mediated through IgE signaling which triggers mast cell degranulation.[30] Recently, IgE-independent "pseudo-allergic" reactions are thought to also be mediated via the MRGPRX2 receptor activation of mast cells (e.g. drugs such as muscle relaxants, opioids, Icatibant and fluoroquinolones).[32]

Many forms of cutaneous and mucosal allergy are mediated in large part by mast cells; they play a central role in asthma, eczema, itch (from various causes), allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis. Antihistamine drugs act by blocking histamine action on nerve endings. Cromoglicate-based drugs (sodium cromoglicate, nedocromil) block a calcium channel essential for mast cell degranulation, stabilizing the cell and preventing release of histamine and related mediators. Leukotriene antagonists (such as montelukast and zafirlukast) block the action of leukotriene mediators and are being used increasingly in allergic diseases.[7]

Calcium triggers the secretion of histamine from mast cells after previous exposure to sodium fluoride. The secretory process can be divided into a fluoride-activation step and a calcium-induced secretory step. It was observed that the fluoride-activation step is accompanied by an elevation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels within the cells. The attained high levels of cAMP persist during histamine release. It was further found that catecholamines do not markedly alter the fluoride-induced histamine release. It was also confirmed that the second, but not the first, step in sodium fluoride-induced histamine secretion is inhibited by theophylline.[33] Vasodilation and increased permeability of capillaries are a result of both H1 and H2 receptor types.[34]

Stimulation of histamine activates a histamine (H2)-sensitive adenylate cyclase of oxyntic cells, and there is a rapid increase in cellular [cAMP] that is involved in activation of H+ transport and other associated changes of oxyntic cells.[35]

Anaphylaxis

[edit]In anaphylaxis (a severe systemic reaction to allergens, such as nuts, bee stings, or drugs), the body-wide degranulation of mast cells leads to vasodilation and, if severe, symptoms of life-threatening shock.[36][37] Products released from these granules include histamine, serotonin, heparin, chondroitin sulphate, tryptase, chymase, carboxypeptidase, and TNF-α.[36] These can vary in their quantities and proportions between individuals, which may explain some of the differences in symptoms seen across patients.[36]

Histamine is a vasodilatory substance released during anaphylaxis.[34]

Autoimmunity

[edit]Mast cells may be implicated in the pathology associated with autoimmune, inflammatory disorders of the joints. They have been shown to be involved in the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the joints (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) and skin (e.g., bullous pemphigoid), and this activity is dependent on antibodies and complement components.[38]

Mastocytosis and clonal disorders

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2015) |

Mastocytosis is a rare clonal mast cell disorder involving the presence of too many mast cells (mastocytes) and CD34+ mast cell precursors.[39] Mutations in c-Kit are associated with mastocytosis.[30] More specifically, the majority (>80%) of patients with mastocytosis have a mutation at codon 816 in the kinase domain of KIT, known as the KIT D816V mutation.[40][41] This mutation, as well as expression of either CD2 or CD25 (confirmed by immunostaining or flow cytometry), are characteristic of primary clonal/monoclonal mast cell activation syndrome (CMCAS/MMAS).[41] The most commonly affected organs in mastocytosis are the skin and bone marrow.[42]

Monoclonal disorders

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2015) |

Neoplastic disorders

[edit]Mastocytomas, or mast cell tumors, can secrete excessive quantities of degranulation products.[30][31] They are often seen in dogs and cats.[43] Other neoplastic disorders associated with mast cells include mast cell sarcoma and mast cell leukemia.

Mast cell activation syndrome

[edit]Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) is an idiopathic immune disorder that involves recurrent and excessive mast cell degranulation and which produces symptoms that are similar to other mast cell activation disorders.[30][31] The syndrome is diagnosed based upon four sets of criteria involving treatment response, symptoms, a differential diagnosis, and biomarkers of mast cell degranulation.[30][31]

History

[edit]Mast cells were first described by Paul Ehrlich in his 1878 doctoral thesis on the basis of their unique staining characteristics and large granules. These granules also led him to the incorrect belief that they existed to nourish the surrounding tissue, so he named them Mastzellen (from German Mast 'fattening', as of animals).[44][45] They are now considered to be part of the immune system.

Research

[edit]Autism

[edit]Research into an immunological contribution to autism suggests that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) children may present with "allergic-like" problems in the absence of elevated serum IgE and chronic urticaria, suggesting non-allergic mast cell activation in response to environmental and stress triggers. This mast cell activation could contribute to brain inflammation and neurodevelopmental problems.[46]

Histological staining

[edit]Toluidine blue: one of the most common stains for acid mucopolysaccharides and glycoaminoglycans, components of mast cells granules.[47]

Bismarck brown: stains mast cell granules brown.[48]

Surface markers: cell surface markers of mast cells were discussed in detail by Heneberg,[49] claiming that mast cells may be inadvertently included in the stem or progenitor cell isolates, since part of them is positive for the CD34 antigen. The classical mast cell markers include the high-affinity IgE receptor, CD117 (c-Kit), and CD203c (for most of the mast cell populations). Expression of some molecules may change in course of the mast cell activation.[50]

Heterogeneity

[edit]Mast cell heterogeneity significantly impacts the efficacy of mast cell stabilizing drugs disodium cromoglycate and ketotifen in preventing mediator release. In experiments, ketotifen inhibits mast cells from lung and tonsillar tissues when stimulated via an IgE-dependent histamine release mechanism, while disodium cromoglycate is less effective but still inhibited these mast cells. However, both agents fail to inhibit mediator release from skin mast cells, indicating that these cells are unresponsive to these stabilizers. Such differences in mast cell activation suggests the existence of different mast cell types across various tissues—a topic of ongoing research.[51][52]

Other organisms

[edit]Mast cells and enterochromaffin cells are the source of most serotonin in the stomach in rodents.[53]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "labrocytes". Memidex. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul (1878). "Beiträge zur Theorie und Praxis der Histologischen Färbung". Leipzig University.

- ^ a b c da Silva EZ, Jamur MC, Oliver C (2014). "Mast cell function: a new vision of an old cell". J. Histochem. Cytochem. 62 (10): 698–738. doi:10.1369/0022155414545334. PMC 4230976. PMID 25062998.

Mast cells can recognize pathogens through different mechanisms including direct binding of pathogens or their components to PAMP receptors on the mast cell surface, binding of antibody or complement-coated bacteria to complement or immunoglobulin receptors, or recognition of endogenous peptides produced by infected or injured cells (Hofmann and Abraham 2009). The pattern of expression of these receptors varies considerably among different mast cell subtypes. TLRs (1–7 and 9), NLRs, RLRs, and receptors for complement are accountable for most mast cell innate responses

- ^ a b c d Polyzoidis S, Koletsa T, Panagiotidou S, Ashkan K, Theoharides TC (2015). "Mast cells in meningiomas and brain inflammation". J Neuroinflammation. 12 (1) 170. doi:10.1186/s12974-015-0388-3. PMC 4573939. PMID 26377554.

MCs originate from a bone marrow progenitor and subsequently develop different phenotype characteristics locally in tissues. Their range of functions is wide and includes participation in allergic reactions, innate and adaptive immunity, inflammation, and autoimmunity [34]. In the human brain, MCs can be located in various areas, such as the pituitary stalk, the pineal gland, the area postrema, the choroid plexus, thalamus, hypothalamus, and the median eminence [35]. In the meninges, they are found within the dural layer in association with vessels and terminals of meningeal nociceptors [36]. MCs have a distinct feature compared to other hematopoietic cells in that they reside in the brain [37]. MCs contain numerous granules and secrete an abundance of prestored mediators such as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), neurotensin (NT), substance P (SP), tryptase, chymase, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TNF, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and varieties of chemokines and cytokines some of which are known to disrupt the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [38–40].

[The] key role of MCs in inflammation [34] and in the disruption of the BBB [41–43] suggests areas of importance for novel therapy research. Increasing evidence also indicates that MCs participate in neuroinflammation directly [44–46] and through microglia stimulation [47], contributing to the pathogenesis of such conditions such as headaches, [48] autism [49], and chronic fatigue syndrome [50]. In fact, a recent review indicated that peripheral inflammatory stimuli can cause microglia activation [51], thus possibly involving MCs outside the brain. - ^ Franco CB, Chen CC, Drukker M, Weissman IL, Galli SJ (2010). "Distinguishing mast cell and granulocyte differentiation at the single-cell level". Cell Stem Cell. 6 (4): 361–8. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.013. PMC 2852254. PMID 20362540.

- ^ Marieb EN, Hoehn K (2004). Human Anatomy and Physiology (6th ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 805. ISBN 978-0-321-20413-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Prussin C, Metcalfe DD (February 2003). "4. IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 111 (2 Suppl): S486–94. doi:10.1067/mai.2003.120. PMC 2847274. PMID 12592295.

- ^ Razin E; Cordon-Cardo C; Good RA (April 1981). "Growth of a pure population of mouse mast cells in vitro with conditioned medium derived from concanavalin A-stimulated splenocytes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 78 (4): 2559–61. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.2559R. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.4.2559. PMC 319388. PMID 6166010.

- ^ Razin E, Ihle JN, Seldin D, et al. (March 1984). "Interleukin 3: A differentiation and growth factor for the mouse mast cell that contains chondroitin sulfate E proteoglycan". Journal of Immunology. 132 (3): 1479–86. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.132.3.1479. PMID 6198393. S2CID 22811807.

- ^ Denburg JA (1998). Allergy and allergic diseases: the new mechanisms and therapeutics. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. ISBN 978-0-89603-404-4.[page needed]

- ^ Pal, Sarit; Gasheva, Olga Y.; Zawieja, David C.; Meininger, Cynthia J.; Gashev, Anatoliy A. (March 2020). "Histamine-mediated autocrine signaling in mesenteric perilymphatic mast cells". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 318 (3): R590-604. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00255.2019. PMC 7099465. PMID 31913658.

- ^ a b c d e Moon TC, Befus AD, Kulka M (2014). "Mast cell mediators: their differential release and the secretory pathways involved". Front Immunol. 5: 569. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00569. PMC 4231949. PMID 25452755.

Two types of degranulation have been described for MC: piecemeal degranulation (PMD) and anaphylactic degranulation (AND) (Figures 1 and 2). Both PMD and AND occur in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro in MC in human (78–82), mouse (83), and rat (84). PMD is selective release of portions of the granule contents, without granule-to-granule and/or granule-to-plasma membrane fusions. ... In contrast to PMD, AND is the explosive release of granule contents or entire granules to the outside of cells after granule-to-granule and/or granule-to-plasma membrane fusions (Figures 1 and 2). Ultrastructural studies show that AND starts with granule swelling and matrix alteration after appropriate stimulation (e.g., FcεRI-crosslinking).

Figure 1: Mediator release from mast cells Archived 29 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

Figure 2: Model of genesis of mast cell secretory granules Archived 29 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

Figure 3: Lipid body biogenesis Archived 29 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

Table 2: Stimuli-selective mediator release from mast cells Archived 29 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Pulendran B, Ono SJ (May 2008). "A shot in the arm for mast cells". Nat. Med. 14 (5): 489–90. doi:10.1038/nm0508-489. PMID 18463655. S2CID 205378470.

- ^ Lee J, Veatch SL, Baird B, Holowka D (2012). "Molecular mechanisms of spontaneous and directed mast cell motility". J. Leukoc. Biol. 92 (5): 1029–41. doi:10.1189/jlb.0212091. PMC 3476239. PMID 22859829.

- ^ Möllerherm, Helene; von Köckritz-Blickwede, Maren; Branitzki-Heinemann, Katja (18 July 2016). "Antimicrobial Activity of Mast Cells: Role and Relevance of Extracellular DNA Traps". Frontiers in Immunology. 7: 265. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00265. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 4947581. PMID 27486458.

- ^ Ashmole I, Bradding P (May 2013). "Ion channels regulating mast cell biology". Clin. Exp. Allergy. 43 (5): 491–502. doi:10.1111/cea.12043. PMID 23600539. S2CID 1127584.

P2X receptors are ligand-gated non-selective cation channels that are activated by extracellular ATP. ... Increased local ATP concentrations are likely to be present around mast cells in inflamed tissues due to its release through cell injury or death and platelet activation [40]. Furthermore, mast cells themselves store ATP within secretory granules, which is released upon activation [41]. There is therefore the potential for significant Ca2+ influx into mast cells through P2X receptors. Members of the P2X family differ in both the ATP concentration they require for activation and the degree to which they desensitise following agonist activation [37, 38]. This opens up the possibility that by expressing a number of different P2X receptors mast cells may be able to tailor their response to ATP in a concentration dependent manner [37].

- ^ Wilhelm M, Silver R, Silverman AJ (November 2005). "Central nervous system neurons acquire mast cell products via transgranulation". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (9): 2238–48. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04429.x. PMC 3281766. PMID 16262662.

- ^ Ren H, Han R, Chen X, Liu X, Wan J, Wang L, Yang X, Wang J (May 2020). "Potential therapeutic targets for intracerebral hemorrhage-associated inflammation: An update". J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 40 (9): 1752–1768. doi:10.1177/0271678X20923551. PMC 7446569. PMID 32423330.

- ^ a b Budzyński J, Kłopocka M (2014). "Brain-gut axis in the pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection". World J. Gastroenterol. 20 (18): 5212–25. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5212. PMC 4017036. PMID 24833851.

In digestive tissue, H. pylori can alter signaling in the brain-gut axis by mast cells, the main brain-gut axis effector

- ^ a b Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C (2015). "The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems". Ann Gastroenterol. 28 (2): 203–209. PMC 4367209. PMID 25830558.

- ^ a b c d Wouters MM, Vicario M, Santos J (2015). "The role of mast cells in functional GI disorders". Gut. 65 (1): 155–168. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309151. PMID 26194403.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are characterized by chronic complaints arising from disorganized brain-gut interactions leading to dysmotility and hypersensitivity. The two most prevalent FGIDs, affecting up to 16–26% of worldwide population, are functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. ... It is well established that mast cell activation can generate epithelial and neuro-muscular dysfunction and promote visceral hypersensitivity and altered motility patterns in FGIDs, postoperative ileus, food allergy and inflammatory bowel disease.

▸ Mast cells play a central pathophysiological role in IBS and possibly in functional dyspepsia, although not well defined.

▸ Increased mast cell activation is a common finding in the mucosa of patients with functional GI disorders. ...

▸ Treatment with mast cell stabilisers offers a reasonably safe and promising option for the management of those patients with IBS non-responding to conventional approaches, though future studies are warranted to evaluate efficacy and indications. - ^ a b Kinet JP (1999). "The high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI): from physiology to pathology". Annual Review of Immunology. 17: 931–72. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.931. PMID 10358778.

- ^ a b c Abbas AK, Lichtman AH, Pillai S (2011). "Role of Mast Cells, Basophils and Eosinophils in Immediate Hypersensitivity". Cellular and Molecular Immunology (7th ed.). New York, NY: Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-1528-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b Rivera J, Cordero JR, Furumoto Y, et al. (September 2002). "Macromolecular protein signaling complexes and mast cell responses: a view of the organization of IgE-dependent mast cell signaling". Molecular Immunology. 38 (16–18): 1253–8. doi:10.1016/S0161-5890(02)00072-X. PMID 12217392.

- ^ Li W, Deanin GG, Margolis B, Schlessinger J, Oliver JM (July 1992). "FcεR1-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins, including phospholipase Cγ1 and the receptor βγ2 complex, in RBL-2H3 rat basophilic leukemia cells". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 12 (7): 3176–82. doi:10.1128/MCB.12.7.3176. PMC 364532. PMID 1535686.

- ^ Pundir, Priyanka; Liu, Rui; Vasavda, Chirag; Serhan, Nadine; Limjunyawong, Nathachit; Yee, Rebecca; Zhan, Yingzhuan; Dong, Xintong; Wu, Xueqing; Zhang, Ying; Snyder, Solomon H; Gaudenzio, Nicolas; Vidal, Jorge E; Dong, Xinzhong (July 2019). "A Connective Tissue Mast-Cell-Specific ReceptorDetects Bacterial Quorum-Sensing Moleculesand Mediates Antibacterial Immunity". Cell Host & Microbe. 26 (1): 114–122. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2019.06.003. PMC 6649664. PMID 31278040. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Tatemoto, Kazuhiko; Nozaki, Yuko; Tsuda, Ryoko; Konno, Shinobu; Tomura, Keiko; Furuno, Masahiro; Ogasawara, Hiroyuki; Edamura, Koji; Takagi, Hideo; Iwamura, Hiroyuki; Noguchi, Masato; Naito, Takayuki (2006). "Immunoglobulin E-independent activation of mast cell is mediated by Mrg receptors". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 349 (4): 1322–1328. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.177. PMID 16979137. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Huang, Hua; Li, Yapeng; Liu, Bing (September 2016). "Transcriptional regulation of mast cell and basophil lineage commitment". Seminars in Immunopathology. 38 (5): 539–548. doi:10.1007/s00281-016-0562-4. ISSN 1863-2297. PMC 5010465. PMID 27126100.

- ^ a b Annunziato, Francesco; Romagnani, Chiara; Romagnani, Sergio (March 2015). "The 3 major types of innate and adaptive cell-mediated effector immunity". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 135 (3): 626–635. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.001. PMID 25528359.

- ^ a b c d e f g Frieri M (2018). "Mast Cell Activation Syndrome". Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 54 (3): 353–365. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8487-6. PMID 25944644. S2CID 5723622.

Table 1

Classification of diseases associated with mast cell activation from Akin et al. [14]

1. Primary

a. Anaphylaxis with an associated clonal mast cell disorder

b. Monoclonal mast cell activation syndrome (MMAS), see text for explanation

2. Secondary

a. Allergic disorders

b. Mast cell activation associated with chronic inflammatory or neoplastic disorders

c. Physical urticarias (requires a primary stimulation)

d. Chronic autoimmune urticaria

3. Idiopathic (When mast cell degranulation has been documented; may be either primary or secondary. Angioedema may be associated with hereditary or acquired angioedema where it may be mast cell independent and result from kinin generation)

a. Anaphylaxis

b. Angioedema

c. Urticaria

d. Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS)...

Recurrent idiopathic anaphylaxis presents with allergic signs and symptoms—hives and angioedema which is a distinguishing feature—eliminates identifiable allergic etiologies, considers mastocytosis and carcinoid syndrome, and is treated with H1 and H2 antihistamines, epinephrine, and steroids [21, 22]. - ^ a b c d e Akin C, Valent P, Metcalfe DD (2010). "Mast cell activation syndrome: Proposed diagnostic criteria". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 126 (6): 1099–104.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.035. PMC 3753019. PMID 21035176.

- ^ Kumar M, Duraisamy K, Chow BK (May 2021). "Unlocking the Non-IgE Mediated Pseudo-Allergic Reaction Puzzle with Mas-Related G-Protein Coupled Receptor Member X2 (MRGPRX2)". Cells. 10 (5): 1033. doi:10.3390/cells10051033. PMC 8146469. PMID 33925682.

- ^ Alm PE (April 1983). "Sodium fluoride evoked histamine release from mast cells. A study of cyclic AMP levels and effects of catecholamines". Agents and Actions. 13 (2–3): 132–7. doi:10.1007/bf01967316. PMID 6191542. S2CID 6977280.

- ^ a b Dachman WD, Bedarida G, Blaschke TF, Hoffman BB (March 1994). "Histamine-induced venodilation in human beings involves both H1 and H2 receptor subtypes". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 93 (3): 606–14. doi:10.1016/S0091-6749(94)70072-9. PMID 8151062.

- ^ Machen TE, Rutten MJ, Ekblad EB (February 1982). "Histamine, cAMP, and activation of piglet gastric mucosa". The American Journal of Physiology. 242 (2): G79–84. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.2.G79. PMID 6175225.

- ^ a b c Gülen, Theo (25 October 2023). "A Puzzling Mast Cell Trilogy: Anaphylaxis, MCAS, and Mastocytosis". Diagnostics. 13 (21): 3307. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13213307. ISSN 2075-4418. PMC 10647312. PMID 37958203.

- ^ Gülen, Theo; Akin, Cem (1 February 2022). "Anaphylaxis and Mast Cell Disorders". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. Allergic and Non-Allergic Systemic Reactions including Anaphylaxis. 42 (1): 45–63. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2021.09.007. ISSN 0889-8561. PMID 34823750.

- ^ Lee DM, Friend DS, Gurish MF, Benoist C, Mathis D, Brenner MB (September 2002). "Mast cells: a cellular link between autoantibodies and inflammatory arthritis". Science. 297 (5587): 1689–92. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.1689L. doi:10.1126/science.1073176. PMID 12215644. S2CID 38504601.

- ^ Horny HP, Sotlar K, Valent P (2007). "Mastocytosis: state of the art". Pathobiology. 74 (2): 121–32. doi:10.1159/000101711. PMID 17587883.

- ^ Arock, M; Sotlar, K; Akin, C; Broesby-Olsen, S; Hoermann, G; Escribano, L; Kristensen, T K; Kluin-Nelemans, H C; Hermine, O; Dubreuil, P; Sperr, W R; Hartmann, K; Gotlib, J; Cross, N C P; Haferlach, T (June 2015). "KIT mutation analysis in mast cell neoplasms: recommendations of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis". Leukemia. 29 (6): 1223–1232. doi:10.1038/leu.2015.24. ISSN 0887-6924. PMC 4522520. PMID 25650093.

- ^ a b Jackson, Clayton Webster; Pratt, Cristina Marie; Rupprecht, Chase Preston; Pattanaik, Debendra; Krishnaswamy, Guha (19 October 2021). "Mastocytosis and Mast Cell Activation Disorders: Clearing the Air". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (20) 11270. doi:10.3390/ijms222011270. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8540348. PMID 34681933.

- ^ Hartmann, Karin; Escribano, Luis; Grattan, Clive; Brockow, Knut; Carter, Melody C.; Alvarez-Twose, Ivan; Matito, Almudena; Broesby-Olsen, Sigurd; Siebenhaar, Frank; Lange, Magdalena; Niedoszytko, Marek; Castells, Mariana; Oude Elberink, Joanna N.G.; Bonadonna, Patrizia; Zanotti, Roberta (January 2016). "Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: Consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 137 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.034. PMID 26476479.

- ^ "Cutaneous Mast Cell Tumors". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Ehrlich P (1878). Beiträge zur Theorie und Praxis der histologischen Färbung [Contribution to the theory and practice of histological dyes] (Dissertation) (in German). Leipzig University. OCLC 63372150.

- ^ "Mastocyte - Definition". Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.[full citation needed]

- ^ Theoharides TC, Angelidou A, Alysandratos KD, et al. (January 2012). "Mast cell activation and autism". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1822 (1): 34–41. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.017. PMID 21193035.

- ^ Blumenkrantz N, Asboe-Hansen G (May 1975). "A selective stain for mast cells". The Histochemical Journal. 7 (3): 277–82. doi:10.1007/BF01003596. PMID 47855. S2CID 32711203.

- ^ Tomov, N.; Dimitrov, N. (2017). "Modified bismarck brown staining for demonstration of soft tissue mast cells" (PDF). Trakia Journal of Sciences. 15 (3): 195–197. doi:10.15547/tjs.2017.03.001.

- ^ Heneberg P (November 2011). "Mast cells and basophils: trojan horses of conventional lin- stem/progenitor cell isolates". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 17 (34): 3753–71. doi:10.2174/138161211798357881. PMID 22103846.

- ^ Lebduska P, Korb J, Tůmová M, Heneberg P, Dráber P (December 2007). "Topography of signaling molecules as detected by electron microscopy on plasma membrane sheets isolated from non-adherent mast cells". Journal of Immunological Methods. 328 (1–2): 139–51. doi:10.1016/j.jim.2007.08.015. PMID 17900607.

- ^ Finn DF, Walsh JJ (September 2013). "Twenty-first century mast cell stabilizers". Br J Pharmacol. 170 (1): 23–37. doi:10.1111/bph.12138. PMC 3764846. PMID 23441583.

- ^ Zhang L; Song J; Hou X (April 2016). "Mast Cells and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: From the Bench to the Bedside". J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 22 (2): 181–192. doi:10.5056/jnm15137. PMC 4819856. PMID 26755686. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2025.

- ^ Fujimiya, Mineko; Inui, Akio (2000). "Peptidergic regulation of gastrointestinal motility in rodents". Peptides. 21 (10). Elsevier BV: 1565–1582. doi:10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00313-2. ISSN 0196-9781. PMID 11068106. S2CID 45185196.

External links

[edit]- Mast+cells at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)