Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Osteoblast

View on Wikipedia| Osteoblast | |

|---|---|

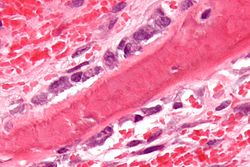

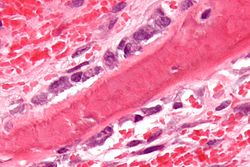

Osteoblasts (purple) rimming a bony spicule (pink - on diagonal of image). In this routinely fixed and decalcified (bone mineral removed) tissue, the osteoblasts have retracted and are separated from each other and from their underlying matrix. In living bone, the cells are linked by tight junctions and gap junctions, and integrated with underlying osteocytes and matrix H&E stain. | |

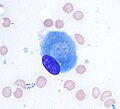

Illustration showing a single osteoblast | |

| Details | |

| Location | Bone |

| Function | Formation of bone tissue |

| Identifiers | |

| Greek | osteoblastus |

| MeSH | D010006 |

| TH | H2.00.03.7.00002 |

| FMA | 66780 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Osteoblasts (from the Greek combining forms for "bone", ὀστέο-, osteo- and βλαστάνω, blastanō "germinate") are cells with a single nucleus that synthesize bone. However, in the process of bone formation, osteoblasts function in groups of connected cells. Individual cells cannot make bone. A group of organized osteoblasts together with the bone made by a unit of cells is usually called the osteon.

Osteoblasts are specialized, terminally differentiated products of mesenchymal stem cells.[1] They synthesize dense, crosslinked collagen and specialized proteins in much smaller quantities, including osteocalcin and osteopontin, which compose the organic matrix of bone.

In organized groups of disconnected cells, osteoblasts produce hydroxyapatite, the bone mineral, that is deposited in a highly regulated manner, into the inorganic matrix forming a strong and dense mineralized tissue, the mineralized matrix. Hydroxyapatite-coated bone implants often perform better as those not coated with this material. For instance, in patients with fatty liver disease hydroxyapatite-coated titanium implants perform better as those not-coated with this material.[2] The mineralized skeleton is the main support for the bodies of air breathing vertebrates. It is also an important store of minerals for physiological homeostasis including both acid–base balance and calcium or phosphate maintenance.[3][4]

Bone structure

[edit]The skeleton is a large organ that is formed and degraded throughout life in the air-breathing vertebrates. The skeleton, often referred to as the skeletal system, is important both as a supporting structure and for maintenance of calcium, phosphate, and acid–base status in the whole organism.[5] The functional part of bone, the bone matrix, is entirely extracellular. The bone matrix consists of protein and mineral. The protein forms the organic matrix. It is synthesized and then the mineral is added. The vast majority of the organic matrix is collagen, which provides tensile strength. The matrix is mineralized by deposition of hydroxyapatite (alternative name, hydroxylapatite). This mineral is hard, and provides compressive strength. Thus, the collagen and mineral together are a composite material with excellent tensile and compressive strength, which can bend under a strain and recover its shape without damage. This is called elastic deformation. Forces that exceed the capacity of bone to behave elastically may cause failure, typically bone fractures.[citation needed]

Bone remodeling

[edit]Bone is a dynamic tissue that is constantly being reshaped by osteoblasts, which produce and secrete matrix proteins and transport mineral into the matrix, and osteoclasts, which break down the tissues.

Osteoblasts

[edit]Osteoblasts are the major cellular component of bone. Osteoblasts arise from mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). MSC give rise to osteoblasts, adipocytes, and myocytes among other cell types. Osteoblast quantity is understood to be inversely proportional to that of marrow adipocytes which comprise marrow adipose tissue (MAT). Osteoblasts are found in large numbers in the periosteum, the thin connective tissue layer on the outside surface of bones, and in the endosteum.

Normally, almost all of the bone matrix, in the air breathing vertebrates, is mineralized by the osteoblasts. Before the organic matrix is mineralized, it is called the osteoid. Osteoblasts buried in the matrix are called osteocytes. During bone formation, the surface layer of osteoblasts consists of cuboidal cells, called active osteoblasts. When the bone-forming unit is not actively synthesizing bone, the surface osteoblasts are flattened and are called inactive osteoblasts. Osteocytes remain alive and are connected by cell processes to a surface layer of osteoblasts. Osteocytes have important functions in skeletal maintenance.

Osteoclasts

[edit]Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells that derive from hematopoietic progenitors in the bone marrow which also give rise to monocytes in peripheral blood.[6] Osteoclasts break down bone tissue, and along with osteoblasts and osteocytes form the structural components of bone. In the hollow within bones are many other cell types of the bone marrow. Components that are essential for osteoblast bone formation include mesenchymal stem cells (osteoblast precursor) and blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients for bone formation. Bone is a highly vascular tissue, and active formation of blood vessel cells, also from mesenchymal stem cells, is essential to support the metabolic activity of bone. The balance of bone formation and bone resorption tends to be negative with age, particularly in post-menopausal women,[7] often leading to a loss of bone serious enough to cause fractures, which is called osteoporosis.

Osteogenesis

[edit]Bone is formed by one of two processes: endochondral ossification or intramembranous ossification. Endochondral ossification is the process of forming bone from cartilage and this is the usual method. This form of bone development is the more complex form: it follows the formation of a first skeleton of cartilage made by chondrocytes, which is then removed and replaced by bone, made by osteoblasts. Intramembranous ossification is the direct ossification of mesenchyme as happens during the formation of the membrane bones of the skull and others.[8]

During osteoblast differentiation, the developing progenitor cells express the regulatory transcription factor Cbfa1/Runx2. A second required transcription factor is Sp7 transcription factor.[9] Osteochondroprogenitor cells differentiate under the influence of growth factors, although isolated mesenchymal stem cells in tissue culture may also form osteoblasts under permissive conditions that include vitamin C and substrates for alkaline phosphatase, a key enzyme that provides high concentrations of phosphate at the mineral deposition site.[1] In turn osteoblasts may give rise to osteocytes in a process dependent on the vascular musculature of blood vessels in the bone.[10]

Bone morphogenetic proteins

[edit]Key growth factors in endochondral skeletal differentiation include bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) that determine to a major extent where chondrocyte differentiation occurs and where spaces are left between bones. The system of cartilage replacement by bone has a complex regulatory system. BMP2 also regulates early skeletal patterning. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), is part of a superfamily of proteins that include BMPs, which possess common signaling elements in the TGF beta signaling pathway. TGF-β is particularly important in cartilage differentiation, which generally precedes bone formation for endochondral ossification. An additional family of essential regulatory factors is the fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) that determine where skeletal elements occur in relation to the skin

Steroid and protein hormones

[edit]Many other regulatory systems are involved in the transition of cartilage to bone and in bone maintenance. A particularly important bone-targeted hormonal regulator is parathyroid hormone (PTH). Parathyroid hormone is a protein made by the parathyroid gland under the control of serum calcium activity.[4] PTH also has important systemic functions, including to keep serum calcium concentrations nearly constant regardless of calcium intake. Increasing dietary calcium results in minor increases in blood calcium. However, this is not a significant mechanism supporting osteoblast bone formation, except in the condition of low dietary calcium; further, abnormally high dietary calcium raises the risk of serious health consequences not directly related to bone mass including heart attack and stroke.[11] Intermittent PTH stimulation increases osteoblast activity, although PTH is bifunctional and mediates bone matrix degradation at higher concentrations.

The skeleton is also modified for reproduction and in response to nutritional and other hormone stresses; it responds to steroids, including estrogen and glucocorticoids, which are important in reproduction and energy metabolism regulation. Bone turnover involves major expenditures of energy for synthesis and degradation, involving many additional signals including pituitary hormones. Two of these are adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)[12] and follicle stimulating hormone.[13] The physiological role for responses to these, and several other glycoprotein hormones, is not fully understood, although it is likely that ACTH is bifunctional, like PTH, supporting bone formation with periodic spikes of ACTH, but causing bone destruction in large concentrations. In mice, mutations that reduce the efficiency of ACTH-induced glucocorticoid production in the adrenals cause the skeleton to become dense (osteosclerotic bone).[14][15]

Organization and ultrastructure

[edit]In well-preserved bone studied at high magnification via electron microscopy, individual osteoblasts are shown to be connected by tight junctions, which prevent extracellular fluid passage and thus create a bone compartment separate from the general extracellular fluid.[16] The osteoblasts are also connected by gap junctions, small pores that connect osteoblasts, allowing the cells in one cohort to function as a unit.[17] The gap junctions also connect deeper layers of cells to the surface layer (osteocytes when surrounded by bone). This was demonstrated directly by injecting low molecular weight fluorescent dyes into osteoblasts and showing that the dye diffused to surrounding and deeper cells in the bone-forming unit.[18] Bone is composed of many of these units, which are separated by impermeable zones with no cellular connections, called cement lines.

Collagen and accessory proteins

[edit]Almost all of the organic (non-mineral) component of bone is dense collagen type I,[19] which forms dense crosslinked ropes that give bone its tensile strength. By mechanisms still unclear, osteoblasts secrete layers of oriented collagen, with the layers parallel to the long axis of the bone alternating with layers at right angles to the long axis of the bone every few micrometers. Defects in collagen type I cause the commonest inherited disorder of bone, called osteogenesis imperfecta.[20]

Minor, but important, amounts of small proteins, including osteocalcin and osteopontin, are secreted in bone's organic matrix.[21] Osteocalcin is not expressed at significant concentrations except in bone, and thus osteocalcin is a specific marker for bone matrix synthesis.[22] These proteins link organic and mineral component of bone matrix.[23] The proteins are necessary for maximal matrix strength due to their intermediate localization between mineral and collagen.

However, in mice where expression of osteocalcin or osteopontin was eliminated by targeted disruption of the respective genes (knockout mice), accumulation of mineral was not notably affected, indicating that organization of matrix is not significantly related to mineral transport.[24][25]

Bone versus cartilage

[edit]The primitive skeleton is cartilage, a solid avascular (without blood vessels) tissue in which individual cartilage-matrix secreting cells, or chondrocytes, occur. Chondrocytes do not have intercellular connections and are not coordinated in units. Cartilage is composed of a network of collagen type II held in tension by water-absorbing proteins, hydrophilic proteoglycans.[26] This is the adult skeleton in cartilaginous fishes such as sharks. It develops as the initial skeleton in more advanced classes of animals.

In air-breathing vertebrates, cartilage is replaced by cellular bone. A transitional tissue is mineralized cartilage. Cartilage mineralizes by massive expression of phosphate-producing enzymes, which cause high local concentrations of calcium and phosphate that precipitate.[26] This mineralized cartilage is not dense or strong. In the air breathing vertebrates it is used as a scaffold for formation of cellular bone made by osteoblasts, and then it is removed by osteoclasts, which specialize in degrading mineralized tissue.

Osteoblasts produce an advanced type of bone matrix consisting of dense, irregular crystals of hydroxyapatite, packed around the collagen ropes.[27] This is a strong composite material that allows the skeleton to be shaped mainly as hollow tubes. Reducing the long bones to tubes reduces weight while maintaining strength.

Mineralization of bone

[edit]The mechanisms of mineralization are not fully understood. Fluorescent, low-molecular weight compounds such as tetracycline or calcein bind strongly to bone mineral, when administered for short periods. They then accumulate in narrow bands in the new bone.[28] These bands run across the contiguous group of bone-forming osteoblasts. They occur at a narrow (sub-micrometer) mineralization front. Most bone surfaces express no new bone formation, no tetracycline uptake and no mineral formation. This strongly suggests that facilitated or active transport, coordinated across the bone-forming group, is involved in bone formation, and that only cell-mediated mineral formation occurs. That is, dietary calcium does not create mineral by mass action.

The mechanism of mineral formation in bone is clearly distinct from the phylogenetically older process by which cartilage is mineralized: tetracycline does not label mineralized cartilage at narrow bands or in specific sites, but diffusely, in keeping with a passive mineralization mechanism.[27]

Osteoblasts separate bone from the extracellular fluid by tight junctions [16] by regulated transport. Unlike in cartilage, phosphate and calcium cannot move in or out by passive diffusion, because the tight osteoblast junctions isolate the bone formation space. Calcium is transported across osteoblasts by facilitated transport (that is, by passive transporters, which do not pump calcium against a gradient).[27] In contrast, phosphate is actively produced by a combination of secretion of phosphate-containing compounds, including ATP, and by phosphatases that cleave phosphate to create a high phosphate concentration at the mineralization front. Alkaline phosphatase is a membrane-anchored protein that is a characteristic marker expressed in large amounts at the apical (secretory) face of active osteoblasts.

At least one more regulated transport process is involved. The stoichiometry of bone mineral basically is that of hydroxyapatite precipitating from phosphate, calcium, and water at a slightly alkaline pH:[29]

- 6 HPO2−4 + 2 H2O + 10 Ca2+ ⇌ Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 + 8 H+

In a closed system as mineral precipitates, acid accumulates, rapidly lowering the pH and stopping further precipitation. Cartilage presents no barrier to diffusion and acid therefore diffuses away, allowing precipitation to continue. In the osteon, where matrix is separated from extracellular fluid by tight junctions, this cannot occur. In the controlled, sealed compartment, removing H+ drives precipitation under a wide variety of extracellular conditions, as long as calcium and phosphate are available in the matrix compartment.[30] The mechanism by which acid transits the barrier layer remains uncertain. Osteoblasts have capacity for Na+/H+ exchange via the redundant Na/H exchangers, NHE1 and NHE6.[31] This H+ exchange is a major element in acid removal, although the mechanism by which H+ is transported from the matrix space into the barrier osteoblast is not known.

In bone removal, a reverse transport mechanism uses acid delivered to the mineralized matrix to drive hydroxyapatite into solution.[32]

Osteocyte feedback

[edit]Feedback from physical activity maintains bone mass, while feedback from osteocytes limits the size of the bone-forming unit.[33][34][35] An important additional mechanism is secretion by osteocytes, buried in the matrix, of sclerostin, a protein that inhibits a pathway that maintains osteoblast activity. Thus, when the osteon reaches a limiting size, it deactivates bone synthesis.[36]

Morphology and histological staining

[edit]Hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) shows that the cytoplasm of active osteoblasts is slightly basophilic due to the substantial presence of rough endoplasmic reticulum. The active osteoblast produces substantial collagen type I. About 10% of the bone matrix is collagen with the balance mineral.[29] The osteoblast's nucleus is spherical and large. An active osteoblast is characterized morphologically by a prominent Golgi apparatus that appears histologically as a clear zone adjacent to the nucleus. The products of the cell are mostly for transport into the osteoid, the non-mineralized matrix. Active osteoblasts can be labeled by antibodies to Type-I collagen, or using naphthol phosphate and the diazonium dye fast blue to demonstrate alkaline phosphatase enzyme activity directly.

-

Osteoblast (Wright Giemsa stain, 100x)

-

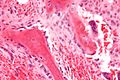

Light micrograph of decalcified cancellous bone displaying osteoblasts actively synthesizing osteoid, containing two osteocytes

-

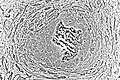

Light micrograph of undecalcified tissue displaying osteoblasts actively synthesizing osteoid (center)

-

Light micrograph of undecalcified tissue displaying osteoblasts actively synthesizing rudimentary bone tissue (center)

-

Osteoblasts lining bone (H&E stain)

Isolation of Osteoblasts

[edit]- The first isolation technique by microdissection method was originally described by Fell et al.[37] using chick limb bones which were separated into periosteum and remaining parts. She obtained cells which possessed osteogenic characteristics from cultured tissue using chick limb bones which were separated into periosteum and remaining parts. She obtained cells which possessed osteogenic characteristics from cultured tissue.

- Enzymatic digestion is one of the most advanced techniques for isolating bone cell populations and obtaining osteoblasts. Peck et al. (1964)[38] described the original method that is now often used by many researchers.

- In 1974 Jones et al.[39] found that osteoblasts moved laterally in vivo and in vitro under different experimental conditions and described the migration method in detail. The osteoblasts were, however, contaminated by cells migrating from the vascular openings, which might include endothelial cells and fibroblasts.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR (April 1999). "Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells". Science. 284 (5411): 143–7. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..143P. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.143. PMID 10102814.

- ^ Pinto TS, van der Eerden BC, Schreuders-Koedam M, van de Peppel J, Ayada I, Pan Q, Verstegen MM, van der Laan LJ, Fuhler GM, Zambuzzi WF, Peppelenbosch MP (November 2024). "Interaction of high lipogenic states with titanium on osteogenesis". Bone. 189: 117256. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2024.117242. PMID 39209139.

- ^ Arnett T (2003). "Regulation of bone cell function by acid–base balance". Proc Nutr Soc. 62 (2): 511–20. doi:10.1079/pns2003268. PMID 14506899.

- ^ a b Blair HC, Zaidi M, Huang CL, Sun L (November 2008). "The developmental basis of skeletal cell differentiation and the molecular basis of major skeletal defects". Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 83 (4): 401–15. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00048.x. PMID 18710437. S2CID 20459725.

- ^ Blair HC, Sun L, Kohanski RA (November 2007). "Balanced regulation of proliferation, growth, differentiation, and degradation in skeletal cells". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1116 (1): 165–73. Bibcode:2007NYASA1116..165B. doi:10.1196/annals.1402.029. PMID 17646258. S2CID 22605157.

- ^ Loutit, J.F.; Nisbet, N.W. (January 1982). "The Origin of Osteoclasts". Immunobiology. 161 (3–4): 193–203. doi:10.1016/S0171-2985(82)80074-0. PMID 7047369.

- ^ Nicks KM, Fowler TW, Gaddy D (June 2010). "Reproductive hormones and bone". Curr Osteoporos Rep. 8 (2): 60–7. doi:10.1007/s11914-010-0014-3. PMID 20425612. S2CID 43825140.

- ^ Larsen, William J. (2001). Human embryology (3. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 355–357. ISBN 0-443-06583-7.

- ^ Karsenty G (2008). "Transcriptional control of skeletogenesis". Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 9: 183–96. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164437. PMID 18767962.

- ^ Fernandes CJ, Silva RA, Ferreira MR, Fuhler GM, Peppelenbosch MP, van der Eerden BC, Zambuzzi WF (August 2024). "Vascular smooth muscle cell-derived exosomes promote osteoblast-to-osteocyte transition via β-catenin signaling". Experimental Cell Research. 442 (1) 114211. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2024.114211. PMID 39147261.

- ^ Reid IR, Bristow SM, Bolland MJ (April 2015). "Cardiovascular complications of calcium supplements". J. Cell. Biochem. 116 (4): 494–501. doi:10.1002/jcb.25028. PMID 25491763. S2CID 40654125.

- ^ Zaidi M, Sun L, Robinson LJ, Tourkova IL, Liu L, Wang Y, Zhu LL, Liu X, Li J, Peng Y, Yang G, Shi X, Levine A, Iqbal J, Yaroslavskiy BB, Isales C, Blair HC (May 2010). "ACTH protects against glucocorticoid-induced osteonecrosis of bone". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (19): 8782–7. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8782Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912176107. PMC 2889316. PMID 20421485.

- ^ Sun L, Peng Y, Sharrow AC, Iqbal J, Zhang Z, Papachristou DJ, Zaidi S, Zhu LL, Yaroslavskiy BB, Zhou H, Zallone A, Sairam MR, Kumar TR, Bo W, Braun J, Cardoso-Landa L, Schaffler MB, Moonga BS, Blair HC, Zaidi M (April 2006). "FSH directly regulates bone mass". Cell. 125 (2): 247–60. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.051. PMID 16630814. S2CID 7544706.

- ^ Hoekstra M, Meurs I, Koenders M, Out R, Hildebrand RB, Kruijt JK, Van Eck M, Van Berkel TJ (April 2008). "Absence of HDL cholesteryl ester uptake in mice via SR-BI impairs an adequate adrenal glucocorticoid-mediated stress response to fasting". J. Lipid Res. 49 (4): 738–45. doi:10.1194/jlr.M700475-JLR200. hdl:2066/69489. PMID 18204096.

- ^ Martineau C, Martin-Falstrault L, Brissette L, Moreau R (January 2014). "The atherogenic Scarb1 null mouse model shows a high bone mass phenotype". Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 306 (1): E48–57. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00421.2013. PMC 3920004. PMID 24253048.

- ^ a b Arana-Chavez VE, Soares AM, Katchburian E (August 1995). "Junctions between early developing osteoblasts of rat calvaria as revealed by freeze-fracture and ultrathin section electron microscopy". Arch. Histol. Cytol. 58 (3): 285–92. doi:10.1679/aohc.58.285. PMID 8527235.

- ^ Doty SB (1981). "Morphological evidence of gap junctions between bone cells". Calcif. Tissue Int. 33 (5): 509–12. doi:10.1007/BF02409482. PMID 6797704. S2CID 29501339.

- ^ Yellowley CE, Li Z, Zhou Z, Jacobs CR, Donahue HJ (February 2000). "Functional gap junctions between osteocytic and osteoblastic cells". J. Bone Miner. Res. 15 (2): 209–17. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.2.209. PMID 10703922. S2CID 7632980.

- ^ Reddi AH, Gay R, Gay S, Miller EJ (December 1977). "Transitions in collagen types during matrix-induced cartilage, bone, and bone marrow formation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (12): 5589–92. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5589R. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5589. PMC 431820. PMID 271986.

- ^ Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G, Prockop DJ (April 1991). "Mutations in collagen genes: causes of rare and some common diseases in humans". FASEB J. 5 (7): 2052–60. doi:10.1096/fasebj.5.7.2010058. PMID 2010058. S2CID 24461341.

- ^ Aubin JE, Liu F, Malaval L, Gupta AK (August 1995). "Osteoblast and chondroblast differentiation". Bone. 17 (2 Suppl): 77S – 83S. doi:10.1016/8756-3282(95)00183-E. PMID 8579903.

- ^ Delmas PD, Demiaux B, Malaval L, Chapuy MC, Meunier PJ (April 1986). "[Osteocalcin (or bone gla-protein), a new biological marker for studying bone pathology]". Presse Med (in French). 15 (14): 643–6. PMID 2939433.

- ^ Roach HI (June 1994). "Why does bone matrix contain non-collagenous proteins? The possible roles of osteocalcin, osteonectin, osteopontin and bone sialoprotein in bone mineralisation and resorption". Cell Biol. Int. 18 (6): 617–28. doi:10.1006/cbir.1994.1088. PMID 8075622. S2CID 20913443.

- ^ Boskey AL, Gadaleta S, Gundberg C, Doty SB, Ducy P, Karsenty G (September 1998). "Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopic analysis of bones of osteocalcin-deficient mice provides insight into the function of osteocalcin". Bone. 23 (3): 187–96. doi:10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00092-1. PMID 9737340.

- ^ Thurner PJ, Chen CG, Ionova-Martin S, Sun L, Harman A, Porter A, Ager JW, Ritchie RO, Alliston T (June 2010). "Osteopontin deficiency increases bone fragility but preserves bone mass". Bone. 46 (6): 1564–73. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.02.014. PMC 2875278. PMID 20171304.

- ^ a b Blair HC, Zaidi M, Schlesinger PH (June 2002). "Mechanisms balancing skeletal matrix synthesis and degradation". Biochem. J. 364 (Pt 2): 329–41. doi:10.1042/BJ20020165. PMC 1222578. PMID 12023876.

- ^ a b c Blair HC, Robinson LJ, Huang CL, Sun L, Friedman PA, Schlesinger PH, Zaidi M (2011). "Calcium and bone disease". BioFactors. 37 (3): 159–67. doi:10.1002/biof.143. PMC 3608212. PMID 21674636.

- ^ Frost HM (1969). "Tetracycline-based histological analysis of bone remodeling". Calcif Tissue Res. 3 (1): 211–37. doi:10.1007/BF02058664. PMID 4894738. S2CID 9373656.

- ^ a b Neuman WF, Neuman MW (1958-01-01). The Chemical Dynamics of Bone Mineral. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-57512-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)[page needed] - ^ Schartum S, Nichols G (May 1962). "Concerning pH gradients between the extracellular compartment and fluids bathing the bone mineral surface and their relation to calcium ion distribution". J. Clin. Invest. 41 (5): 1163–8. doi:10.1172/JCI104569. PMC 291024. PMID 14498063.

- ^ Liu L, Schlesinger PH, Slack NM, Friedman PA, Blair HC (June 2011). "High capacity Na+/H+ exchange activity in mineralizing osteoblasts". J. Cell. Physiol. 226 (6): 1702–12. doi:10.1002/jcp.22501. PMC 4458346. PMID 21413028.

- ^ Blair HC, Teitelbaum SL, Ghiselli R, Gluck S (August 1989). "Osteoclastic bone resorption by a polarized vacuolar proton pump". Science. 245 (4920): 855–7. Bibcode:1989Sci...245..855B. doi:10.1126/science.2528207. PMID 2528207.

- ^ Klein-Nulend J, Nijweide PJ, Burger EH (June 2003). "Osteocyte and bone structure". Curr Osteoporos Rep. 1 (1): 5–10. doi:10.1007/s11914-003-0002-y. PMID 16036059. S2CID 9456704.

- ^ Dance, Amber (23 February 2022). "Fun facts about bones: More than just scaffolding". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-022222-1. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Robling, Alexander G.; Bonewald, Lynda F. (10 February 2020). "The Osteocyte: New Insights". Annual Review of Physiology. 82 (1): 485–506. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-021119-034332. hdl:1805/30982. ISSN 0066-4278. PMC 8274561. PMID 32040934.

- ^ Baron, Roland; Rawadi, Georges; Roman-Roman, Sergio (2006). "WNT Signaling: A Key Regulator of Bone Mass". Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Vol. 76. pp. 103–127. doi:10.1016/S0070-2153(06)76004-5. ISBN 978-0-12-153176-8. PMID 17118265.

- ^ Fell, HB (January 1932). "The Osteogenic Capacity in vitro of Periosteum and Endosteum Isolated from the Limb Skeleton of Fowl Embryos and Young Chicks". Journal of Anatomy. 66 (Pt 2): 157–180.11. PMC 1248877. PMID 17104365.

- ^ Peck, W. A.; Birge, S. J.; Fedak, S. A. (11 December 1964). "Bone Cells: Biochemical and Biological Studies after Enzymatic Isolation". Science. 146 (3650): 1476–1477. Bibcode:1964Sci...146.1476P. doi:10.1126/science.146.3650.1476. PMID 14208576. S2CID 26903706.

- ^ Jones, S.J.; Boyde, A. (December 1977). "Some morphological observations on osteoclasts". Cell and Tissue Research. 185 (3): 387–97. doi:10.1007/bf00220298. PMID 597853. S2CID 26078285.

Further reading

[edit]- William F. Neuman and Margaret W. Neuman. (1958). The Chemical Dynamics of Bone Mineral. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-57512-8.

- Netter, Frank H. (1987). Musculoskeletal system: anatomy, physiology, and metabolic disorders. Summit, New Jersey: Ciba-Geigy Corporation ISBN 0-914168-88-6.