Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Life-cycle assessment

View on Wikipedia

Life cycle assessment (LCA), also known as life cycle analysis, is a methodology for assessing the impacts associated with all the stages of the life cycle of a commercial product, process, or service. For instance, in the case of a manufactured product, environmental impacts are assessed from raw material extraction and processing (cradle), through the product's manufacture, distribution and use, to the recycling or final disposal of the materials composing it (grave).[1][2]

An LCA study involves a thorough inventory of the energy and materials that are required across the supply chain and value chain of a product, process or service, and calculates the corresponding emissions to the environment.[2] LCA thus assesses cumulative potential environmental impacts. The aim is to document and improve the overall environmental profile of the product[2] by serving as a holistic baseline upon which carbon footprints can be accurately compared.

The LCA method is based on ISO 14040 (2006) and ISO 14044 (2006) standards.[3][4] Widely recognized procedures for conducting LCAs are included in the ISO 14000 series of environmental management standards of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), in particular, in ISO 14040 and ISO 14044. ISO 14040 provides the 'principles and framework' of the Standard, while ISO 14044 provides an outline of the 'requirements and guidelines'. Generally, ISO 14040 was written for a managerial audience and ISO 14044 for practitioners.[5] As part of the introductory section of ISO 14040, LCA has been defined as the following:[6]

LCA studies the environmental aspects and potential impacts throughout a product's life cycle (i.e., cradle-to-grave) from raw materials acquisition through production, use and disposal. The general categories of environmental impacts needing consideration include resource use, human health, and ecological consequences.

Criticisms have been leveled against the LCA approach, both in general and with regard to specific cases (e.g., in the consistency of the methodology, the difficulty in performing, the cost in performing, revealing of intellectual property, and the understanding of system boundaries). When the understood methodology of performing an LCA is not followed, it can be completed based on a practitioner's views or the economic and political incentives of the sponsoring entity (an issue plaguing all known data-gathering practices). In turn, an LCA completed by 10 different parties could yield 10 different results. The ISO LCA Standard aims to normalize this; however, the guidelines are not overly restrictive and 10 different answers may still be generated.[5]

Definition, synonyms, goals, and purpose

[edit]Life cycle assessment (LCA) is sometimes referred to synonymously as life cycle analysis in the scholarly and agency report literatures.[7][1][8] Also, due to the general nature of an LCA study of examining the life cycle impacts from raw material extraction (cradle) through disposal (grave), it is sometimes referred to as "cradle-to-grave analysis".[6]

As stated by the National Risk Management Research Laboratory of the EPA, "LCA is a technique to assess the environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product, process, or service, by:

- Compiling an inventory of relevant energy and material inputs and environmental releases

- Evaluating the potential environmental impacts associated with identified inputs and releases

- Interpreting the results to help you make a more informed decision".[2]

Hence, it is a technique to assess environmental impacts associated with all the stages of a product's life from raw material extraction through materials processing, manufacture, distribution, use, repair and maintenance, and disposal or recycling. The results are used to help decision-makers select products or processes that result in the least impact to the environment by considering an entire product system and avoiding sub-optimization that could occur if only a single process were used.[9]

Therefore, the goal of LCA is to compare the full range of environmental effects assignable to products and services by quantifying all inputs and outputs of material flows and assessing how these material flows affect the environment.[10] This information is used to improve processes, support policy and provide a sound basis for informed decisions.

The term life cycle refers to the notion that a fair, holistic assessment requires the assessment of raw-material production, manufacture, distribution, use and disposal including all intervening transportation steps necessary or caused by the product's existence.[11]

Despite attempts to standardize LCA, results from different LCAs are often contradictory, therefore it is unrealistic to expect these results to be unique and objective. Thus, it should not be considered as such, but rather as a family of methods attempting to quantify results through different points-of-view.[12] Among these methods are two main types: Attributional LCA and Consequential LCA.[13] Attributional LCAs seek to attribute the burdens associated with the production and use of a product, or with a specific service or process, for an identified temporal period.[14] Consequential LCAs seek to identify the environmental consequences of a decision or a proposed change in a system under study, and thus are oriented to the future and require that market and economic implications must be taken into account.[14] In other words, Attributional LCA "attempts to answer 'how are things (i.e. pollutants, resources, and exchanges among processes) flowing within the chosen temporal window?', while Consequential LCA attempts to answer 'how will flows beyond the immediate system change in response to decisions?"[9]

A third type of LCA, termed "social LCA", is also under development and is a distinct approach to that is intended to assess potential social and socio-economic implications and impacts.[15] Social life cycle assessment (SLCA) is a useful tool for companies to identify and assess potential social impacts along the lifecycle of a product or service on various stakeholders (for example: workers, local communities, consumers).[16] SLCA is framed by the UNEP/SETAC's Guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products published in 2009 in Quebec.[17] The tool builds on the ISO 26000:2010 Guidelines for Social Responsibility and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Guidelines.[18]

The limitations of LCA to focus solely on the ecological aspects of sustainability, and not the economical or social aspects, distinguishes it from product line analysis (PLA) and similar methods. This limitation was made deliberately to avoid method overload but recognizes these factors should not be ignored when making product decisions.[6]

Some widely recognized procedures for LCA are included in the ISO 14000 series of environmental management standards, in particular, ISO 14040 and 14044.[19][page needed][20][page needed][21] Greenhouse gas (GHG) product life cycle assessments can also comply with specifications such as Publicly Available Specification (PAS) 2050 and the GHG Protocol Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard.[22][23]

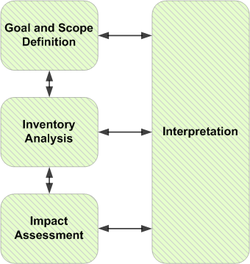

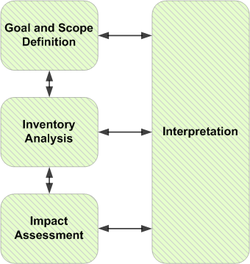

Main ISO phases of LCA

[edit]According to standards in the ISO 14040 and 14044, an LCA is carried out in four distinct phases,[6][19][page needed][20][page needed] as illustrated in the figure shown at the above right (at opening of the article). The phases are often interdependent, in that the results of one phase will inform how other phases are completed. Therefore, none of the stages should be considered finalized until the entire study is complete.[5]

Goal and scope

[edit]An LCA study begins with a goal and scope definition phase, which includes the product function, functional unit, product system and its boundaries, assumptions, data categories, allocation procedures, and review method to be employed in the analysis.[24] The ISO LCA Standard requires a series of parameters to be quantitatively and qualitatively expressed, which are occasionally referred to as study design parameters (SPDs). The two main SPDs for an LCA are the goal and scope, both which must be explicitly stated.[5]

Generally, an LCA study starts with a clear statement of its goal, outlining the study's context and detailing how and to whom the results will be communicated. Per ISO guidelines, the goal must unambiguously state the following items:

- The intended application

- Reasons for carrying out the study

- The audience

- Whether the results will be used in a comparative assertion released publicly[5][25]

The goal should also be defined with the commissioner for the study, and it is recommended a detailed description for why the study is being carried out is acquired from the commissioner.[25]

Following the goal, the scope must be defined by outlining the qualitative and quantitative information included in the study. Unlike the goal, which may only include a few sentences, the scope often requires multiple pages.[5] It is set to describe the detail and depth of the study and demonstrate that the goal can be achieved within the stated limitations.[25] Under the ISO LCA Standard guidelines, the scope of the study should outline the following:[26]

- Product system, which is a collection of processes (activities that transform inputs to outputs) that are needed to perform a specified function and are within the system boundary of the study. It is representative of all the processes in the life cycle of a product or process.[5][25]

- Functional unit, which defines precisely what is being studied, quantifies the service delivered by the system, provides a reference to which the inputs and outputs can be related, and provides a basis for comparing/analyzing alternative goods or services.[27] The functional unit is a very important component of LCA and needs to be clearly defined.[25] It is used as a basis for selecting one or more product systems that can provide the function. Therefore, the functional unit enables different systems to be treated as functionally equivalent. The defined functional unit should be quantifiable, include units, consider temporal coverage, and not contain product system inputs and outputs (e.g., kg CO2 emissions).[5] Another way to look at it is by considering the following questions:

- What?

- How much?

- For how long / how many times?

- Where?

- How well?[13]

- Reference flow, which is the amount of product or energy that is needed to realize the functional unit.[25][13] Typically, the reference flow is different qualitatively and quantitatively for different products or systems across the same reference flow; however, there are instances where they can be the same.[13]

- System boundary, which delimits which processes should be included in the analysis of a product system, including whether the system produces any co-products that must be accounted for by system expansion or allocation.[28] The system boundary should be in accordance with the stated goal of the study.[5]

- Assumptions and limitations,[25] which includes any assumptions or decisions made throughout the study that may influence the final results. It is important these are made transparent as their omission may result in misinterpretation of the results. Additional assumptions and limitations necessary to accomplish the project are often made throughout the project and should recorded as necessary.[9]

- Data quality requirements, which specify the kinds of data that will be included and what restrictions.[29] According to ISO 14044, the following data quality considerations should be documented in the scope:

- Temporal coverage

- Geographical coverage

- Technological coverage

- Precision, completeness, and representativeness of the data

- Consistency and reproducibility of the methods used in the study

- Sources of data

- Uncertainty of information and any recognized data gaps[25]

- Allocation procedure, which is used to partition the inputs and outputs of a product and is necessary for processes that produce multiple products, or co-products.[25] This is also known as multifunctionality of a product system.[13] ISO 14044 presents a hierarchy of solutions to deal with multifunctionality issues, as the choice of allocation method for co-products can significantly impact results of an LCA.[30] The hierarchy methods are as follows:

- Avoid Allocation by Sub-Division - this method attempts to disaggregate the unit process into smaller sub-processes in order to separate the production of the product from the production of the co-product.[13][31]

- Avoid Allocation through System Expansion (or substitution) - this method attempts to expand the process of the co-product with the most likely way of providing the secondary function of the determining product (or reference product). In other words, by expanding the system of the co-product in the most likely alternative way of producing the co-product independently (System 2). The impacts resulting from the alternative way of producing the co-product (System 2) are then subtracted from the determining product to isolate the impacts in System 1.[13]

- Allocation (or partition) based on Physical Relationship - this method attempts to divide inputs and outputs and allocate them based on physical relationships between the products (e.g., mass, energy-use, etc.).[13][31]

- Allocation (or partition) based on Other Relationship (non-physical) - this method attempts to divide inputs and outputs and allocate them based on non-physical relationships (e.g., economic value).[13][31]

- Impact assessment, which includes an outline of the impact categories identified under interest for the study, and the selected methodology used to calculate the respective impacts. Specifically, life cycle inventory data is translated into environmental impact scores,[13][31] which might include such categories as human toxicity, smog, global warming, and eutrophication.[29] As part of the scope, only an overview needs to be provided, as the main analysis on the impact categories is discussed in the Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) phase of the study.

- Documentation of data, which is the explicit documentation of the inputs/outputs (individual flows) used within the study. This is necessary as most analyses do not consider all inputs and outputs of a product system, so this provides the audience with a transparent representation of the selected data. It also provides transparency for why the system boundary, product system, functional unit, etc. was chosen.[31]

Life cycle inventory (LCI)

[edit]

Life cycle inventory (LCI) analysis involves creating an inventory of flows from and to nature (ecosphere) for a product system.[32] It is the process of quantifying raw material and energy requirements, atmospheric emissions, land emissions, water emissions, resource uses, and other releases over the life cycle of a product or process.[33] In other words, it is the aggregation of all elementary flows related to each unit process within a product system.

To develop the inventory, it is often recommended to start with a flow model of the technical system using data on inputs and outputs of the product system.[33][34] The flow model is typically illustrated with a flow diagram that includes the activities that are going to be assessed in the relevant supply chain and gives a clear picture of the technical system boundaries.[34] Generally, the more detailed and complex the flow diagram, the more accurate the study and results.[33] The input and output data needed for the construction of the model is collected for all activities within the system boundary, including from the supply chain (referred to as inputs from the technosphere).[34]

According to ISO 14044, an LCI should be documented using the following steps:

- Preparation of data collection based on goal and scope

- Data collection

- Data validation (even if using another work's data)

- Data allocation (if needed)

- Relating data to the unit process

- Relating data to the functional unit

- Data aggregation[35][36]

As referenced in the ISO 14044 standard, the data must be related to the functional unit, as well as the goal and scope. However, since the LCA stages are iterative in nature, the data collection phase may cause the goal or scope to change.[26] Conversely, a change in the goal or scope during the course of the study may cause additional collection of data or removal of previously collected data in the LCI.[35]

The output of an LCI is a compiled inventory of elementary flows from all of the processes in the studied product system(s). The data is typically detailed in charts and requires a structured approach due to its complex nature.[37]

When collecting the data for each process within the system boundary, the ISO LCA standard requires the study to measure or estimate the data in order to quantitatively represent each process in the product system. Ideally, when collecting data, a practitioner should aim to collect data from primary sources (e.g., measuring inputs and outputs of a process on-site or other physical means).[35] Questionnaire are frequently used to collect data on-site and can even be issued to the respective manufacturer or company to complete. Items on the questionnaire to be recorded may include:

- Product for data collection

- Data collector and date

- Period of data collection

- Detailed explanation of the process

- Inputs (raw materials, ancillary materials, energy, transportation)

- Outputs (emissions to air, water, and land)

- Quantity and quality of each input and output[38]

Oftentimes, the collection of primary data may be difficult and deemed proprietary or confidential by the owner.[39] An alternative to primary data is secondary data, which is data that comes from LCA databases, literature sources, and other past studies. With secondary sources, it is often you find data that is similar to a process but not exact (e.g., data from a different country, slightly different process, similar but different machine, etc.).[40] As such, it is important to explicitly document the differences in such data. However, secondary data is not always inferior to primary data. For example, referencing another work's data in which the author used very accurate primary data.[35] Along with primary data, secondary data should document the source, reliability, and temporal, geographical, and technological representativeness.

When identifying the inputs and outputs to document for each unit process within the product system of an LCI, a practitioner may come across the instance where a process has multiple input streams or generate multiple output streams. In such case, the practitioner should allocate the flows based on the "Allocation procedure"[33][35][38] outlined in the previous "Goal and scope" section of this article.

The technosphere is more simply defined as the human-made world, and considered by geologists as secondary resources, these resources are in theory 100% recyclable; however, in a practical sense, the primary goal is salvage.[41] For an LCI, these technosphere products (supply chain products) are those that have been produced by humans, including products such as forestry, materials, and energy flows.[42] Typically, they will not have access to data concerning inputs and outputs for previous production processes of the product.[43] The entity undertaking the LCA must then turn to secondary sources if it does not already have that data from its own previous studies. National databases or data sets that come with LCA-practitioner tools, or that can be readily accessed, are the usual sources for that information.[44] Care must then be taken to ensure that the secondary data source properly reflects regional or national conditions.[35]

LCI methods include "process-based LCAs", economic input–output LCA (EIOLCA), and hybrid approaches.[37][35] Process-based LCA is a bottom-up LCI approach the constructs an LCI using knowledge about industrial processes within the life cycle of a product, and the physical flows connecting them.[45] EIOLCA is a top-down approach to LCI and uses information on elementary flows associated with one unit of economic activity across different sectors.[46] This information is typically pulled from government agency national statistics tracking trade and services between sectors.[37] Hybrid LCA is a combination of process-based LCA and EIOLCA.[47]

The quality of LCI data is typically evaluated with the use of a pedigree matrix. Different pedigree matrices are available, but all contain a number of data quality indicators and a set of qualitative criteria per indicator.[48][49][50] There is another hybrid approach integrates the widely used, semi-quantitative approach that uses a pedigree matrix, into a qualitative analysis to better illustrate the quality of LCI data for non-technical audiences, in particular policymakers.[51]

Life cycle impact assessment (LCIA)

[edit]Life cycle inventory analysis is followed by a life cycle impact assessment (LCIA). This phase of LCA is aimed at evaluating the potential environmental and human health impacts resulting from the elementary flows determined in the LCI. The ISO 14040 and 14044 standards require the following mandatory steps for completing an LCIA:[52][53][54]

Mandatory

- Selection of impaction categories, category indicators, and characterization models. The ISO Standard requires that a study selects multiple impacts that encompass "a comprehensive set of environmental issues". The impacts should be relevant to the geographical region of the study and justification for each chosen impact should be discussed.[53] Often times in practice, this is completed by choosing an already existing LCIA method (e.g., TRACI, ReCiPe, AWARE, Eco-costs etc.).[52][55]

- Classification of inventory results. In this step, the LCI results are assigned to the chosen impact categories based on their known environmental effects. In practice, this is often completed using LCI databases or LCA software.[52] Common impact categories include Global Warming, Ozone Depletion, Acidification, Human Toxicity, etc.[56]

- Characterization, which quantitatively transforms the LCI results within each impact category via "characterization factors" (also referred to as equivalency factors) to create "impact category indicators."[53] In other words, this step is aimed at answering "how much does each result contribute to the impact category?"[52] A main purpose of this step is to convert all classified flows for an impact into common units for comparison. For example, for Global Warming Potential, the unit is generally defined as CO2-equiv or CO2-e (CO2 equivalents) where CO2 is given a value of 1 and all other units are converted respective to their related impact.[53]

In many LCAs, characterization concludes the LCIA analysis, as it is the last compulsory stage according to ISO 14044.[20][page needed][53] However, the ISO Standard provides the following optional steps to be taken in addition to the aforementioned mandatory steps:

Optional

- Normalization of results. This step aims to answer "Is that a lot?" by expressing the LCIA results in respect to a chosen reference system.[52] A separate reference value is often chosen for each impact category, and the rationale for the step is to provide temporal and spatial perspective and to help validate the LCIA results.[53] Standard references are typical impacts per impact category per: geographical zone, inhabitant of geographical zone (per person), industrial sector, or another product system or baseline reference scenario.[52]

- Grouping of LCIA results. This step is accomplished by sorting or ranking the LCIA results (either characterized or normalized depending on the prior steps chosen) into a single group or several groups as defined within the goal and scope.[52][53] However, grouping is subjective and may be inconsistent across studies.

- Weighting of impact categories. This step aims to determine the significance of each category and how important it is relative to the others. It allows studies to aggregate impact scores into a single indicator for comparison.[52] Weighting is highly subjective and as it is often decided based on the interested parties' ethics.[53] There are three main categories of weighting methods: the panel method, monetization method, and target method.[56] ISO 14044 generally advises against weighting, stating that "weighting, shall not be used in LCA studies intended to be used in comparative assertions intended to be disclosed to the public".[20][page needed] If a study decides to weight results, then the weighted results should always be reported together with the non-weighted results for transparency.[37]

Life cycle impacts can also be categorized under the several phases of the development, production, use, and disposal of a product. Broadly speaking, these impacts can be divided into first impacts, use impacts, and end of life impacts. First impacts include extraction of raw materials, manufacturing (conversion of raw materials into a product), transportation of the product to a market or site, construction/installation, and the beginning of the use or occupancy.[57][58] Use impacts include physical impacts of operating the product or facility (such as energy, water, etc.), and any maintenance, renovation, or repairs that are required to continue to use the product or facility.[59] End of life impacts include demolition and processing of waste or recyclable materials.[60]

Interpretation

[edit]Life cycle interpretation is a systematic technique to identify, quantify, check, and evaluate information from the results of the life cycle inventory and/or the life cycle impact assessment. The results from the inventory analysis and impact assessment are summarized during the interpretation phase. The outcome of the interpretation phase is a set of conclusions and recommendations for the study. According to ISO 14043,[19][61] the interpretation should include the following:

- Identification of significant issues based on the results of the LCI and LCIA phases of an LCA

- Evaluation of the study considering completeness, sensitivity and consistency checks

- Conclusions, limitations and recommendations[61]

A key purpose of performing life cycle interpretation is to determine the level of confidence in the final results and communicate them in a fair, complete, and accurate manner. Interpreting the results of an LCA is not as simple as "3 is better than 2, therefore Alternative A is the best choice".[62] Interpretation begins with understanding the accuracy of the results, and ensuring they meet the goal of the study. This is accomplished by identifying the data elements that contribute significantly to each impact category, evaluating the sensitivity of these significant data elements, assessing the completeness and consistency of the study, and drawing conclusions and recommendations based on a clear understanding of how the LCA was conducted and the results were developed.[63][61]

Specifically, as voiced by M.A. Curran, the goal of the LCA interpretation phase is to identify the alternative that has the least cradle-to-grave environmental negative impact on land, sea, and air resources.[64]

LCA uses

[edit]LCA was primarily used as a comparison tool, providing informative information on the environmental impacts of a product and comparing it to available alternatives.[65] Its potential applications expanded to include marketing, product design, product development, strategic planning, consumer education, ecolabeling and government policy.[66]

ISO specifies three types of classification in regard to standards and environmental labels:

- Type I environmental labelling requires a third-party certification process to verify a products compliance against a set of criteria, according to ISO 14024.

- Type II environmental labels are self-declared environmental claims, according to ISO 14021.

- Type III environmental declaration, also known as environmental product declaration (EPD), uses LCA as a tool to report the environmental performance of a product, while conforming to the ISO standards 14040 and 14044.[67]

EPDs provide a level of transparency that is being increasingly demanded through policies and standards around the world. They are used in the built environment as a tool for experts in the industry to compose whole building life cycle assessments more easily, as the environmental impact of individual products are known.[68]

Data analysis

[edit]A life cycle analysis is only as accurate and valid as is its basis set of data.[69] There are two fundamental types of LCA data–unit process data, and environmental input-output (EIO) data.[70] A unit process data collects data around a single industrial activity and its product(s), including resources used from the environment and other industries, as well as its generated emissions throughout its life cycle.[71] EIO data are based on national economic input-output data.[72]

In 2001, ISO published a technical specification on data documentation, describing the format for life cycle inventory data (ISO 14048).[73] The format includes three areas: process, modeling and validation, and administrative information.[74]

When comparing LCAs, the data used in each LCA should be of equivalent quality, since no just comparison can be done if one product has a much higher availability of accurate and valid data, as compared to another product which has lower availability of such data.[75]

Moreover, time horizon is a sensitive parameter and was shown to introduce inadvertent bias by providing one perspective on the outcome of LCA, when comparing the toxicity potential between petrochemicals and biopolymers for instance.[76] Therefore, conducting sensitivity analysis in LCA are important to determine which parameters considerably impact the results, and can also be used to identify which parameters cause uncertainties.[77]

Data sources used in LCAs are typically large databases.[78] Common data sources include:[79]

As noted above, the inventory in the LCA usually considers a number of stages including materials extraction, processing and manufacturing, product use, and product disposal.[1][2] When an LCA is done on a product across all stages, the stage with the highest environmental impact can be determined and altered.[83] For example, woolen-garment was evaluated on its environmental impacts during its production, use and end-of-life, and identified the contribution of fossil fuel energy to be dominated by wool processing and GHG emissions to be dominated by wool production.[84] However, the most influential factor was the number of garment wear and length of garment lifetime, indicating that the consumer has the largest influence on this products' overall environmental impact.[84]

Variants

[edit]Cradle-to-grave or life cycle assessment

[edit]Cradle-to-grave is the full life cycle assessment from resource extraction ('cradle'), to manufacturing, usage, and maintenance, all the way through to its disposal phase ('grave').[85] For example, trees produce paper, which can be recycled into low-energy production cellulose (fiberised paper) insulation, then used as an energy-saving device in the ceiling of a home for 40 years, saving 2,000 times the fossil-fuel energy used in its production. After 40 years the cellulose fibers are replaced and the old fibers are disposed of, possibly incinerated. All inputs and outputs are considered for all the phases of the life cycle.[86]

Cradle-to-gate

[edit]Cradle-to-gate is an assessment of a partial product life cycle from resource extraction (cradle) to the factory gate (i.e., before it is transported to the consumer). The use phase and disposal phase of the product are omitted in this case. Cradle-to-gate assessments are sometimes the basis for environmental product declarations (EPD) termed business-to-business EPDs.[citation needed] One of the significant uses of the cradle-to-gate approach compiles the life cycle inventory (LCI) using cradle-to-gate. This allows the LCA to collect all of the impacts leading up to resources being purchased by the facility. They can then add the steps involved in their transport to plant and manufacture process to more easily produce their own cradle-to-gate values for their products.[87]

Cradle-to-cradle or closed loop production

[edit]Cradle-to-cradle is a specific kind of cradle-to-grave assessment, where the end-of-life disposal step for the product is a recycling process. It is a method used to minimize the environmental impact of products by employing sustainable production, operation, and disposal practices and aims to incorporate social responsibility into product development.[88][89] From the recycling process originate new, identical products (e.g., asphalt pavement from discarded asphalt pavement, glass bottles from collected glass bottles), or different products (e.g., glass wool insulation from collected glass bottles).[90]

Allocation of burden for products in open loop production systems presents considerable challenges for LCA. Various methods, such as the avoided burden approach have been proposed to deal with the issues involved.[91]

Gate-to-gate

[edit]Gate-to-gate is a partial LCA looking at only one value-added process in the entire production chain. Gate-to-gate modules may also later be linked in their appropriate production chain to form a complete cradle-to-gate evaluation.[92]

Well-to-wheel

[edit]Well-to-wheel (WtW) is the specific LCA used for transport fuels and vehicles. The analysis is often broken down into stages entitled "well-to-station", or "well-to-tank", and "station-to-wheel" or "tank-to-wheel", or "plug-to-wheel". The first stage, which incorporates the feedstock or fuel production and processing and fuel delivery or energy transmission, and is called the "upstream" stage, while the stage that deals with vehicle operation itself is sometimes called the "downstream" stage. The well-to-wheel analysis is commonly used to assess total energy consumption, or the energy conversion efficiency and emissions impact of marine vessels, aircraft and motor vehicles, including their carbon footprint, and the fuels used in each of these transport modes.[93][94][95][96] WtW analysis is useful for reflecting the different efficiencies and emissions of energy technologies and fuels at both the upstream and downstream stages, giving a more complete picture of real emissions.[97]

The well-to-wheel variant has a significant input on a model developed by the Argonne National Laboratory. The Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Transportation (GREET) model was developed to evaluate the impacts of new fuels and vehicle technologies. The model evaluates the impacts of fuel use using a well-to-wheel evaluation while a traditional cradle-to-grave approach is used to determine the impacts from the vehicle itself. The model reports energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and six additional pollutants: volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxide (NOx), particulate matter with size smaller than 10 micrometer (PM10), particulate matter with size smaller than 2.5 micrometer (PM2.5), and sulfur oxides (SOx).[72]

Quantitative values of greenhouse gas emissions calculated with the WTW or with the LCA method can differ, since the LCA is considering more emission sources. For example, while assessing the GHG emissions of a battery electric vehicle in comparison with a conventional internal combustion engine vehicle, the WTW (accounting only the GHG for manufacturing the fuels) concludes that an electric vehicle can save around 50–60% of GHG.[98] On the other hand, using a hybrid LCA-WTW method, concludes that GHG emission savings are 10-13% lower than the WTW results, as the GHG due to the manufacturing and the end of life of the battery are also considered.[99]

Economic input–output life cycle assessment

[edit]Economic input–output LCA (EIOLCA) involves use of aggregate sector-level data on how much environmental impact can be attributed to each sector of the economy and how much each sector purchases from other sectors.[100] Such analysis can account for long chains (for example, building an automobile requires energy, but producing energy requires vehicles, and building those vehicles requires energy, etc.), which somewhat alleviates the scoping problem of process LCA; however, EIOLCA relies on sector-level averages that may or may not be representative of the specific subset of the sector relevant to a particular product and therefore is not suitable for evaluating the environmental impacts of products. Additionally, the translation of economic quantities into environmental impacts is not validated.[101]

Ecologically based LCA

[edit]While a conventional LCA uses many of the same approaches and strategies as an Eco-LCA, the latter considers a much broader range of ecological impacts. It was designed to provide a guide to wise management of human activities by understanding the direct and indirect impacts on ecological resources and surrounding ecosystems. Developed by Ohio State University Center for resilience, Eco-LCA is a methodology that quantitatively takes into account regulating and supporting services during the life cycle of economic goods and products. In this approach services are categorized in four main groups: supporting, regulating, provisioning and cultural services.[102]

Exergy-based LCA

[edit]Exergy of a system is the maximum useful work possible during a process that brings the system into equilibrium with a heat reservoir.[103][104] Wall[105] clearly states the relation between exergy analysis and resource accounting.[106] This intuition confirmed by DeWulf[107] and Sciubba[108] lead to Exergo-economic accounting[109] and to methods specifically dedicated to LCA such as Exergetic material input per unit of service (EMIPS).[110] The concept of material input per unit of service (MIPS) is quantified in terms of the second law of thermodynamics, allowing the calculation of both resource input and service output in exergy terms. This exergetic material input per unit of service (EMIPS) has been elaborated for transport technology. The service not only takes into account the total mass to be transported and the total distance, but also the mass per single transport and the delivery time.[110]

Life cycle energy analysis

[edit]Life cycle energy analysis (LCEA) is an approach in which all energy inputs to a product are accounted for, not only direct energy inputs during manufacture, but also all energy inputs needed to produce components, materials and services needed for the manufacturing process.[111] With LCEA, the total life cycle energy input is established.[112]

Energy production

[edit]It is recognized that much energy is lost in the production of energy commodities themselves, such as nuclear energy, photovoltaic electricity or high-quality petroleum products. Net energy content is the energy content of the product minus energy input used during extraction and conversion, directly or indirectly. A controversial early result of LCEA claimed that manufacturing solar cells requires more energy than can be recovered in using the solar cell.[113] Although these results were true when solar cells were first manufactured, their efficiency increased greatly over the years.[114] Currently, energy payback time of photovoltaic solar panels range from a few months to several years.[115][116] Module recycling could further reduce the energy payback time to around one month.[117] Another new concept that flows from life cycle assessments is energy cannibalism. Energy cannibalism refers to an effect where rapid growth of an entire energy-intensive industry creates a need for energy that uses (or cannibalizes) the energy of existing power plants. Thus, during rapid growth, the industry as a whole produces no energy because new energy is used to fuel the embodied energy of future power plants. Work has been undertaken in the UK to determine the life cycle energy (alongside full LCA) impacts of a number of renewable technologies.[118][119]

Energy recovery

[edit]If materials are incinerated during the disposal process, the energy released during burning can be harnessed and used for electricity production. This provides a low-impact energy source, especially when compared with coal and natural gas.[120] While incineration produces more greenhouse gas emissions than landfills, the waste plants are well-fitted with regulated pollution control equipment to minimize this negative impact. A study comparing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions from landfills (without energy recovery) against incineration (with energy recovery) found incineration to be superior in all cases except for when landfill gas is recovered for electricity production.[121]

Criticism

[edit]Energy efficiency is arguably only one consideration in deciding which alternative process to employ, and should not be elevated as the only criterion for determining environmental acceptability.[122] For example, a simple energy analysis does not take into account the renewability of energy flows or the toxicity of waste products.[123] Incorporating "dynamic LCAs", e.g., with regard to renewable energy technologies—which use sensitivity analyses to project future improvements in renewable systems and their share of the power grid—may help mitigate this criticism.[124][125]

In recent years, the literature on life cycle assessment of energy technology has begun to reflect the interactions between the current electrical grid and future energy technology. Some papers have focused on energy life cycle,[126][127][128] while others have focused on carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases.[129] The essential critique given by these sources is that when considering energy technology, the growing nature of the power grid must be taken into consideration. If this is not done, a given class energy technology may emit more CO2 over its lifetime than it initially thought it would mitigate, with this most well documented {{Citation needed|reason=Please include a study|date=October 2023}} in wind energy's case.

A problem that arises when using the energy analysis method is that different energy forms—heat, electricity, chemical energy etc.—have inconsistent functional units, different quality, and different values.[130] This is due to the fact that the first law of thermodynamics measures the change in internal energy,[131] whereas the second law measures entropy increase.[132] Approaches such as cost analysis or exergy may be used as the metric for LCA, instead of energy.[133]

LCA dataset creation

[edit]There are structured systematic datasets of and for LCAs.

A 2022 dataset provided standardized calculated detailed environmental impacts of >57,000 food products in supermarkets, potentially e.g., informing consumers or policy.[134][135] There also is at least one crowdsourced database for collecting LCA data for food products.[136]

Datasets can also consist of options, activities, or approaches, rather than of products – for example one dataset assesses PET bottle waste management options in Bauru, Brazil.[137] There are also LCA databases about buildings – complex products – which a 2014 study compared.[138]

LCA dataset platforms

[edit]There are some initiatives to develop, integrate, populate, standardize, quality control, combine and maintain such datasets or LCAs[139][140] – for example:

- The goal of the LCA Digital Commons Project of the U.S. National Agricultural Library is "to develop a database and tool set intended to provide data for use in LCAs of food, biofuels, and a variety of other bioproducts".[141]

- The Global LCA Data Access network (GLAD) by the UN's Life Cycle Initiative is a "platform which allows to search, convert and download datasets from different life cycle assessment dataset providers".[142]

- The BONSAI project "aims to build a shared resource where the community can contribute to data generation, validation, and management decisions" for "product footprinting" with its first goal being "to produce an open dataset and an open source toolchain capable of supporting LCA calculations".[143] With product footprints they refer to the goal of "reliable, unbiased sustainability information on products".[144]

Dataset optimization

[edit]Datasets that are suboptimal in accuracy or have gaps can be, temporarily until the complete data is available or permanently, be patched or optimized by various methods such as mechanisms for "selection of a dataset that represents the missing dataset that leads in most cases to a much better approximation of environmental impacts than a dataset selected by default or by geographical proximity"[145] or machine learning.[146][135]

Integration in systems and systems theory

[edit]Life cycle assessments can be integrated as routine processes of systems, as input for modeled future socio-economic pathways, or, more broadly, into a larger context[147] (such as qualitative scenarios).

For example, a study estimated the environmental benefits of microbial protein within a future socio-economic pathway, showing substantial deforestation reduction (56%) and climate change mitigation if only 20% of per-capita beef was replaced by microbial protein by 2050.[148]

Life cycle assessments, including as product/technology analyses, can also be integrated in analyses of potentials, barriers and methods to shift or regulate consumption or production.

The life cycle perspective also allows considering losses and lifetimes of rare goods and services in the economy. For example, the usespans of, often scarce, tech-critical metals were found to be short as of 2022.[149] Such data could be combined with conventional life cycle analyses, e.g., to enable life-cycle material/labor cost analyses and long-term economic viability or sustainable design.[150] One study suggests that in LCAs, resource availability is, as of 2013, "evaluated by means of models based on depletion time, surplus energy, etc."[151]

Broadly, various types of life cycle assessments (or commissioning such) could be used in various ways in various types of societal decision-making,[152][147][153] especially because financial markets of the economy typically do not consider life cycle impacts or induced societal problems in the future and present—the "externalities" to the contemporary economy.[154]

Critiques

[edit]Life cycle assessment is a powerful tool for analyzing commensurable aspects of quantifiable systems.[citation needed] Not every factor, however, can be reduced to a number and inserted into a model. Rigid system boundaries make accounting for changes in the system difficult.[155] This is sometimes referred to as the boundary critique to systems thinking. The accuracy and availability of data can also contribute to inaccuracy. For instance, data from generic processes may be based on averages, unrepresentative sampling, or outdated results.[156] This is especially the case for the use and end of life phases in the LCA.[157] Additionally, social implications of products are generally lacking in LCAs. Comparative life cycle analysis is often used to determine a better process or product to use. However, because of aspects like differing system boundaries, different statistical information, different product uses, etc., these studies can easily be swayed in favor of one product or process over another in one study and the opposite in another study based on varying parameters and different available data.[158] There are guidelines to help reduce such conflicts in results but the method still provides a lot of room for the researcher to decide what is important, how the product is typically manufactured, and how it is typically used.[159][160]

An in-depth review of 13 LCA studies of wood and paper products[161] found a lack of consistency in the methods and assumptions used to track carbon during the product lifecycle. A wide variety of methods and assumptions were used, leading to different and potentially contrary conclusions—particularly with regard to carbon sequestration and methane generation in landfills and with carbon accounting during forest growth and product use.[162]

Recent research has raised substantial concerns regarding the reliability and quality of Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) data for composite materials. Identified issues include incomplete datasets, insufficient transparency, and methodological inconsistencies that have the potential to compromise Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) outcomes [163]. A comparative analysis of 20 databases revealed significant discrepancies in LCI values for identical materials across different sources [164], while further studies have emphasized the magnitude of numerical variation between databases [165]. More recently, investigations applying Benford's law to LCI data have highlighted additional inconsistencies, with deviations observed not only across geographical regions but also within specific environmental compartments [166].

Moreover, the fidelity of LCAs can vary substantially as various data may not be incorporated, especially in early versions: for example, LCAs that do not consider regional emission information can under-estimate the life cycle environmental impact.[167]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ilgin, Mehmet Ali; Gupta, Surendra M. (2010). "Environmentally Conscious Manufacturing and Product Recovery (ECMPRO): A Review of the State of the Art". Journal of Environmental Management. 91 (3): 563–591. Bibcode:2010JEnvM..91..563I. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.09.037. PMID 19853369.

Life cycle analysis (LCA) is a method used to evaluate the environmental impact of a product through its life cycle encompassing extraction and processing of the raw materials, manufacturing, distribution, use, recycling, and final disposal.

. - ^ a b c d e "Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)". EPA.gov. Washington, DC. EPA National Risk Management Research Laboratory (NRMRL). 6 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

LCA is a technique to assess the environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product, process, or service, by: / * Compiling an inventory of relevant energy and material inputs and environmental releases/ * Evaluating the potential environmental impacts associated with identified inputs and releases / * Interpreting the results to help you make a more informed decision

- ^ "ISO 14040:2006". ISO.

- ^ "ISO 14044:2006". ISO.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Matthews, H. Scott, Chris T. Hendrickson, and Deanna H. Matthews (2014). Life Cycle Assessment: Quantitative Approaches for Decisions That Matter. pp. 83–95.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Klopffer, Walter and Birgit Grahl (2014). Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Jonker, Gerald; Harmsen, Jan (2012). "Creating Design Solutions". Engineering for Sustainability. Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier. pp. 61–81, esp. 70. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53846-8.00004-4. ISBN 978-0-444-53846-8.

It is very important to first set the goal of the life cycle analysis or assessment. In the conceptual design stage, the goal in general will be identifying the major environmental impacts of the reference process and showing how the new design reduces these impacts

- ^ Sánchez-Barroso, Gonzalo; Botejara-Antúnez, Manuel; García-Sanz-Calcedo, Justo; Zamora-Polo, Francisco (September 2021). "A life cycle analysis of ionizing radiation shielding construction systems in healthcare buildings". Journal of Building Engineering. 41 102387. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102387. hdl:11441/152353.

- ^ a b c Life Cycle Assessment: Principles and Practice. Cincinnati, Ohio: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2006. pp. 3–9.

- ^ "Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Overview". SFTool. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ "Entry details | FAO Term Portal". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Ekvall, Tomas (2020). "Attributional and Consequential Life Cycle Assessment". Sustainability Assessment at the 21st century. doi:10.5772/intechopen.89202. ISBN 978-1-78984-976-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hauschild, Michael Z., Ralph K. Rosenbaum, & Stig Irving Olsen (2018). Life Cycle Assessment: Theory and Practice. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-3-319-56474-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gong, Jian; You, Fengqi (2017). "Consequential Life Cycle Optimization: General Conceptual Framework and Application to Algal Renewable Diesel Production". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 5 (7): 5887–5911. Bibcode:2017ASCE....5.5887G. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b00631.

- ^ Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Environment Programme, 2009.

- ^ Benoît, Catherine; Mazijn, Bernard. (2013). Guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products. United Nations Environment Programme. OCLC 1059219275.

- ^ Benoît, Catherine; Norris, Gregory A.; Valdivia, Sonia; Ciroth, Andreas; Moberg, Asa; Bos, Ulrike; Prakash, Siddharth; Ugaya, Cassia; Beck, Tabea (February 2010). "The guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products: just in time!". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 15 (2): 156–163. Bibcode:2010IJLCA..15..156B. doi:10.1007/s11367-009-0147-8.

- ^ Garrido, Sara Russo (1 January 2017). "Social Life-Cycle Assessment: An Introduction". In Abraham, Martin A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Sustainable Technologies. Elsevier. pp. 253–265. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-409548-9.10089-2. ISBN 978-0-12-804792-7.

- ^ a b c E.g., see Saling, Peter (2006). ISO 14040: Environmental management—Life cycle assessment, Principles and framework (Report). Geneve, CH: International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Retrieved 11 December 2019.[full citation needed] For the PDF of the 1997 version, see this Stanford University course reading.

- ^ a b c d E.g., see Saling, Peter (2006). ISO 14044: Environmental management—Life cycle assessment, Requirements and guidelines (Report). Geneve, CH: International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Retrieved 11 December 2019.[full citation needed]

- ^ ISO 14044 replaced earlier versions of ISO 14041 to ISO 14043.[citation needed]

- ^ "PAS 2050:2011 Specification for the assessment of the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of goods and services". BSI. Retrieved on: 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Product Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard" Archived 9 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. GHG Protocol. Retrieved on: 25 April 2013.

- ^ Jolliet, Olivier; Saade-Sbeih, Myriam; Shaked, Shanna; Jolliet, Alexandre; Crettaz, Pierre (18 November 2015). Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (PDF). doi:10.1201/b19138. hdl:20.500.12657/43927. ISBN 978-1-4398-8770-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Palsson, Ann-Christin & Ellen Riise (31 August 2011). "Defining the goal and scope of the LCA study" (PDF). Rowan University.

- ^ a b Curran, Mary Ann (2017). "Overview of Goal and Scope Definition in Life Cycle Assessment". Goal and Scope Definition in Life Cycle Assessment. LCA Compendium – the Complete World of Life Cycle Assessment. pp. 1–62. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0855-3_1. ISBN 978-94-024-0854-6.

- ^ Rebitzer, G.; Ekvall, T.; Frischknecht, R.; Hunkeler, D.; Norris, G.; Rydberg, T.; Schmidt, W.-P.; Suh, S.; Weidema, B.P.; Pennington, D.W. (July 2004). "Life cycle assessment". Environment International. 30 (5): 701–720. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2003.11.005. PMID 15051246.

- ^ Finnveden, Göran; Hauschild, Michael Z.; Ekvall, Tomas; Guinée, Jeroen; Heijungs, Reinout; Hellweg, Stefanie; Koehler, Annette; Pennington, David; Suh, Sangwon (October 2009). "Recent developments in Life Cycle Assessment". Journal of Environmental Management. 91 (1): 1–21. Bibcode:2009JEnvM..91....1F. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.06.018. PMID 19716647.

- ^ a b "ISO 14044:2006". ISO. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Flysjö, Anna; Cederberg, Christel; Henriksson, Maria; Ledgard, Stewart (2011). "How does co-product handling affect the carbon footprint of milk? Case study of milk production in New Zealand and Sweden". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 16 (5): 420–430. Bibcode:2011IJLCA..16..420F. doi:10.1007/s11367-011-0283-9.

- ^ a b c d e Matthews, H. Scott; Hendrickson, Chris T.; Matthews, Deanna H. (2014). Life Cycle Assessment: Quantitative Approaches for Decisions that Matter. pp. 174–186.

- ^ Hofstetter, Patrick (1998). Perspectives in Life Cycle Impact Assessment. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-5127-0. ISBN 978-1-4613-7333-9.

- ^ a b c d Life Cycle Assessment: Principles and Practice. Cincinnati, Ohio: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2006. pp. 19–30.

- ^ a b c Cao, C. (2017). "Sustainability and life assessment of high strength natural fibre composites in construction". Advanced High Strength Natural Fibre Composites in Construction. pp. 529–544. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-100411-1.00021-2. ISBN 978-0-08-100411-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Matthew, H. Scott; Hendrickson, Chris T.; Matthews, Deanna H. (2014). Life Cycle Assessment: Quantitative Approaches for Decisions that Matter. pp. 101–112.

- ^ Haque, Nawshad (2020). "The Life Cycle Assessment of Various Energy Technologies". Future Energy. pp. 633–647. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102886-5.00029-3. ISBN 978-0-08-102886-5.

- ^ a b c d Hauschild, Michael Z.; Rosenbaum, Ralph K.; Olsen, Stig Irving (2018). Life Cycle Assessment: Theory and Practice. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 978-3-319-56474-6.

- ^ a b Lee, Kun-Mo; Inaba, Atsushi (2004). Life Cycle Assessment: Best Practices of ISO 14040 Series. Committee on Trade and Investment. pp. 12–19.

- ^ Borgman, Christine L. (2015). Big Data, Little Data, No Data. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9963.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-262-32786-2.[page needed]

- ^ Curran, Mary Ann (2012). "Sourcing Life Cycle Inventory Data". Life Cycle Assessment Handbook. pp. 105–141. doi:10.1002/9781118528372.ch5. ISBN 978-1-118-09972-8.

- ^ Steinbach, V.; Wellmer, F. (May 2010). "Review: Consumption and Use of Non-Renewable Mineral and Energy Raw Materials from an Economic Geology Point of View". Sustainability. 2 (5): 1408–1430. doi:10.3390/su2051408.

- ^ Joyce, P. James; Björklund, Anna (2021). "Futura: A new tool for transparent and shareable scenario analysis in prospective life cycle assessment". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 26 (1): 134–144. doi:10.1111/jiec.13115.

- ^ Moni, Sheikh Moniruzzaman; Mahmud, Roksana; High, Karen; Carbajales-Dale, Michael (2019). "Life cycle assessment of emerging technologies: A review". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 24: 52–63. doi:10.1111/jiec.12965.

- ^ Khasreen, Mohamad Monkiz; Banfill, Phillip F. G.; Menzies, Gillian F. (2009). "Life-Cycle Assessment and the Environmental Impact of Buildings: A Review". Sustainability. 1 (3): 674–701. Bibcode:2009Sust....1..674K. doi:10.3390/su1030674.

- ^ University, Carnegie Mellon. "Approaches to LCA - Economic Input-Output Life Cycle Assessment - Carnegie Mellon University". www.eiolca.net. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Righi, Serena; Dal Pozzo, Alessandro; Tugnoli, Alessandro; Raggi, Andrea; Salieri, Beatrice; Hischier, Roland (2020). "The Availability of Suitable Datasets for the LCA Analysis of Chemical Substances". Life Cycle Assessment in the Chemical Product Chain. pp. 3–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-34424-5_1. ISBN 978-3-030-34423-8.

- ^ Hendrickson, Chris T.; Lave, Lester B.; Matthews, H. Scott (2006). "Hybrid LCA Analysis: Combining the EIO-LCA Approach". Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Goods and Services: An Input-output Approach. Resources for the Future. pp. 21–28. doi:10.4324/9781936331383. ISBN 978-1-933115-23-8.

- ^ Edelen, Ashley; Ingwersen, Wesley W. (April 2018). "The creation, management, and use of data quality information for life cycle assessment". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 23 (4): 759–772. Bibcode:2018IJLCA..23..759E. doi:10.1007/s11367-017-1348-1. PMC 5919259. PMID 29713113.

- ^ Laner, David; Feketitsch, Julia; Rechberger, Helmut; Fellner, Johann (October 2016). "A Novel Approach to Characterize Data Uncertainty in Material Flow Analysis and its Application to Plastics Flows in Austria: Characterization of Uncertainty of MFA Input Data". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 20 (5): 1050–1063. doi:10.1111/jiec.12326.

- ^ Weidema, Bo P. (September 1998). "Multi-user test of the data quality matrix for product life cycle inventory data". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 3 (5): 259–265. Bibcode:1998IJLCA...3..259W. doi:10.1007/BF02979832.

- ^ Salemdeeb, Ramy; Saint, Ruth; Clark, William; Lenaghan, Michael; Pratt, Kimberley; Millar, Fraser (March 2021). "A pragmatic and industry-oriented framework for data quality assessment of environmental footprint tools". Resources, Environment and Sustainability. 3 100019. Bibcode:2021REnvS...300019S. doi:10.1016/j.resenv.2021.100019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hauschild, Michael Z.; Rosenbaum, Ralph K.; Olsen, Stig Irving (2018). Life Cycle Assessment: Theory and Practice. Cham Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. pp. 168–187. ISBN 978-3-319-56474-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Matthews, H. Scott, Chis T. Hendrickson, & Deanna H. Matthews (2014). Life Cycle Assessment: Quantitative Approaches for Decisions that Matter. pp. 373–393.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pizzol, M.; Christensen, P.; Schmidt, J.; Thomsen, M. (April 2011). "Impacts of 'metals' on human health: a comparison between nine different methodologies for Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)". Journal of Cleaner Production. 19 (6–7): 646–656. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.05.007.

- ^ Wu, You; Su, Daizhong (2020). Review of Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) Methods and Inventory Databases. Springer. pp. 39–55. ISBN 978-3-030-39149-2.

- ^ a b Lee, Kun-Mo; Inaba, Atsushi (2004). Life Cycle Assessment: Best Practices of ISO 14040 Series. Committee on Trade and Investment. pp. 41–68.

- ^ Rich, Brian D. (2015). Gines, J.; Carraher, E.; Galarze, J. (eds.). Future-Proof Building Materials: A Life Cycle Analysis. Intersections and Adjacencies. Proceedings of the 2015 Building Educators' Society Conference. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah. pp. 123–130.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Life Cycle Assessment". www.gdrc.org. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Milà i Canals, Llorenç; Bauer, Christian; Depestele, Jochen; Dubreuil, Alain; Knuchel, Ruth Freiermuth; Gaillard, Gérard; Michelsen, Ottar; Müller-Wenk, Ruedi; Rydgren, Bernt (2007). "Key elements in a framework for land use impact assessment within LCA" (PDF). International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 12 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1065/lca2006.05.250. hdl:1854/LU-3219556.

- ^ "Sustainable Management of Construction and Demolition Materials". www.epa.gov. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Lee, Kun-Mo; Inaba, Atsushi (2004). Life Cycle Assessment: Best Practices of ISO 14040 Series. Springer International Publishing. pp. 64–70.

- ^ "TrueValueMetrics ... Impact Accounting for the 21st Century". www.truevaluemetrics.org. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Hauschild, Michael Z.; Rosenbaum; Olsen, Stig Irving (2018). Life Cycle Assessment: Theory and Practice. Cham, Switzerland: Spring International Publishing. pp. 324–334. ISBN 978-3-319-56474-6.

- ^ Curran, Mary Ann. "Life Cycle Analysis: Principles and Practice" (PDF). Scientific Applications International Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Shaked, Shanna; Crettaz, Pierre; Saade-Sbeih, Myriam; Jolliet, Olivier; Jolliet, Alexandre (2015). Environmental Life Cycle Assessment. doab: CRC Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-429-11105-1.

- ^ Golsteijn, Laura (17 July 2020). "Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) explained". pre-sustainability.com. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Ekstrom, Eileen (20 December 2013). "ISO Descriptions of Environmental Labels and Declarations". ecosystem-analytics.com/. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "EPD_System". www.thegreenstandard.org. Archived from the original on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Reap, John; Roman, Felipe; Duncan, Scott; Bra, Bert (14 May 2008). "A survey of unresolved problems in life cycle assessment". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 13 (5): 374–388. Bibcode:2008IJLCA..13..374R. doi:10.1007/s11367-008-0009-9.

- ^ Hendrickson, C.T.; Horvath, A.; Joshi, S.; Klausner, M.; Lave, L.B.; McMichael, F.C. (1997). "Comparing two life cycle assessment approaches: A process model vs. Economic input-output-based assessment". Proceedings of the 1997 IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment. ISEE-1997. pp. 176–181. doi:10.1109/ISEE.1997.605313. ISBN 0-7803-3808-1.

- ^ Joyce Cooper (2015). LCA Digital Commons Unit Process Data: field operations/ work processes and farm implements (Report).

- ^ a b "How Does GREET Work?". Argonne National Laboratory. 3 September 2010. Archived from the original on 8 June 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Environmental management — Life cycle assessment — Data documentation format". ISO. 2002.

- ^ Rebitzer, G.; Ekvall, T.; Frischknecht, R.; Hunkeler, D.; Norris, G.; Rydberg, T.; Schmidt, W.-P.; Suh, S.; Weidema, B.P.; Pennington, D.W. (July 2004). "Life cycle assessment". Environment International. 30 (5): 701–720. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2003.11.005. PMID 15051246.

- ^ Scientific Applications International Corporation (May 2006). "Life cycle assessment: principles and practice" (PDF). p. 88. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2009.

- ^ Guo, M.; Murphy, R.J. (2012). "LCA data quality: Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis". Science of the Total Environment. 435–436: 230–243. Bibcode:2012ScTEn.435..230G. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.07.006. PMID 22854094.

- ^ Groen, E. A.; Heijungs, R.; Bokkers, E. A. M.; de Boer, I. J. M. (October 2014). Sensitivity analysis in life cycle assessment. LCA Food 2014: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment in the Agri-food Sector. San Francisco: American Centre for Life Cycle Assessment. pp. 482–488. ISBN 978-0-9882145-7-6.

- ^ Pagnon, F; Mathern, A; Ek, K (21 November 2020). "A review of online sources of open-access life cycle assessment data for the construction sector". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 588 (4) 042051. Bibcode:2020E&ES..588d2051P. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/588/4/042051.

- ^ "Your source for LCA and sustainability data". openLCA Nexus.

- ^ "HESTIA". HESTIA. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ "CarbonCloud". CarbonCloud. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ "Data License: CEDA 5". VitalMetrics. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Pasqualino, Jorgelina C.; Meneses, Montse; Abella, Montserrat; Castells, Francesc (May 2009). "LCA as a Decision Support Tool for the Environmental Improvement of the Operation of a Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant". Environmental Science & Technology. 43 (9): 3300–3307. Bibcode:2009EnST...43.3300P. doi:10.1021/es802056r. PMID 19534150.

- ^ a b Wiedemann, S.G.; Biggs, L.; Nebel, B.; Bauch, K.; Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G.; Swan, P.G.; Watson, K. (August 2020). "Environmental impacts associated with the production, use, and end-of-life of a woollen garment". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 25 (8): 1486–1499. Bibcode:2020IJLCA..25.1486W. doi:10.1007/s11367-020-01766-0. hdl:10642/10017.

- ^ Gordon, Jason (26 June 2021). "Cradle to Grave - Explained". thebusinessprofessor.com/. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ Zheng, Li-Rong; Tenhunen, Hannu; Zou, Zhuo (2018). Smart electronic systems: heterogeneous integration of silicon and printed electronics. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-33895-5.

- ^ Franklin Associates. "Cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Inventory of Nine Plastic Resins and Four Polyurethane Precursors" (PDF). The Plastics Division of the American Chemistry Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ "Cradle to Cradle Marketplace | Frequently asked Questions". www.cradletocradlemarketplace.com. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "Cradle-to-Cradle". ecomii. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- ^ Huang, Yue; Bird, Roger N.; Heidrich, Oliver (November 2007). "A review of the use of recycled solid waste materials in asphalt pavements". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 52 (1): 58–73. Bibcode:2007RCR....52...58H. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2007.02.002.

- ^ Ijassi, Walid; Rejeb, Helmi Ben; Zwolinski, Peggy (2021). "Environmental Impact Allocation of Agri-food Co-products". Procedia CIRP. 98: 252–257. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2021.01.039.

- ^ Jiménez-González, C.; Kim, S.; Overcash, M. (2000). "Methodology for developing gate-to-gate Life cycle inventory information". Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 5 (3): 153–159. Bibcode:2000IJLCA...5..153J. doi:10.1007/BF02978615.

- ^ Brinkman, Norman; Wang, Michael; Weber, Trudy; Darlington, Thomas (May 2005). "Well-to-Wheels Analysis of Advanced Fuel/Vehicle Systems – A North American Study of Energy Use, Greenhouse Gas Emissions, and Criteria Pollutant Emissions" (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011. See Executive Summary – ES.1 Background, pp1.

- ^ Norm Brinkman; Eberle, Ulrich; Formanski, Volker; Uwe-Dieter Grebe; Matthe, Roland (2012). Vehicle Electrification - Quo Vadis? / Fahrzeugelektrifizierung - Quo Vadis?. 33rd International Vienna Motor Symposium 2012. pp. 186–215. doi:10.13140/2.1.2638.8163. ISBN 978-3-18-374912-6.

- ^ "Full Fuel Cycle Assessment: Well-To-Wheels Energy Inputs, Emissions, and Water Impacts" (PDF). California Energy Commission. 1 August 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Green Car Glossary: Well to wheel". Car Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Liu, Xinyu; Reddi, Krishna; Elgowainy, Amgad; Lohse-Busch, Henning; Wang, Michael; Rustagi, Neha (January 2020). "Comparison of well-to-wheels energy use and emissions of a hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle relative to a conventional gasoline-powered internal combustion engine vehicle". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 45 (1): 972–983. Bibcode:2020IJHE...45..972L. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.10.192. OSTI 1580696.

- ^ Moro A; Lonza L (2018). "Electricity carbon intensity in European Member States: Impacts on GHG emissions of electric vehicles". Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 64: 5–14. Bibcode:2018TRPD...64....5M. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2017.07.012. PMC 6358150. PMID 30740029.

- ^ Moro, A; Helmers, E. (2017). "A new hybrid method for reducing the gap between WTW and LCA in the carbon footprint assessment of electric vehicles". Int J Life Cycle Assess. 22 (1): 4–14. Bibcode:2017IJLCA..22....4M. doi:10.1007/s11367-015-0954-z.

- ^ Hendrickson, C. T., Lave, L. B., and Matthews, H. S. (2005). Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Goods and Services: An Input–Output Approach, Resources for the Future Press ISBN 1-933115-24-6.

- ^ "Limitations of the EIO-LCA Method—Economic Input-Output Life Cycle Assessment". Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2012 – via EIOLCA.net.

- ^ Singh, Shweta; Bakshi, Bhavik R. (2009). "Eco-LCA: A tool for quantifying the role of ecological resources in LCA". 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Sustainable Systems and Technology. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ISSST.2009.5156770. ISBN 978-1-4244-4324-6.

- ^ Rosen, Marc A; Dincer, Ibrahim (January 2001). "Exergy as the confluence of energy, environment and sustainable development". Exergy. 1 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1016/S1164-0235(01)00004-8.

- ^ Wall, Göran; Gong, Mei (2001). "On exergy and sustainable development—Part 1: Conditions and concepts". Exergy. 1 (3): 128–145. doi:10.1016/S1164-0235(01)00020-6.

- ^ Wall, Göran (1977). "Exergy - a useful concept within resource accounting" (PDF).

- ^ Gaudreau, Kyrke (2009). Exergy analysis and resource accounting (MSc). University of Waterloo.

- ^ Dewulf, Jo; Van Langenhove, Herman; Muys, Bart; Bruers, Stijn; Bakshi, Bhavik R.; Grubb, Geoffrey F.; Paulus, D. M.; Sciubba, Enrico (April 2008). "Exergy: Its Potential and Limitations in Environmental Science and Technology". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (7): 2221–2232. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.2221D. doi:10.1021/es071719a. PMID 18504947.

- ^ Sciubba, Enrico (October 2004). "From Engineering Economics to Extended Exergy Accounting: A Possible Path from Monetary to Resource-Based Costing". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 8 (4): 19–40. Bibcode:2004JInEc...8...19S. doi:10.1162/1088198043630397.

- ^ Rocco, M.V.; Colombo, E.; Sciubba, E. (January 2014). "Advances in exergy analysis: a novel assessment of the Extended Exergy Accounting method". Applied Energy. 113: 1405–1420. Bibcode:2014ApEn..113.1405R. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.08.080. hdl:11311/751641.

- ^ a b Dewulf, J.; Van Langenhove, H. (May 2003). "Exergetic material input per unit of service (EMIPS) for the assessment of resource productivity of transport commodities". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 38 (2): 161–174. Bibcode:2003RCR....38..161D. doi:10.1016/S0921-3449(02)00152-0.

- ^ Ramesh, T.; Prakash, Ravi; Shukla, K.K. (2010). "Life cycle energy analysis of buildings: An overview". Energy and Buildings. 42 (10): 1592–1600. Bibcode:2010EneBu..42.1592R. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2010.05.007.

- ^ Cabeza, Luisa F.; Rincón, Lídia; Vilariño, Virginia; Pérez, Gabriel; Castell, Albert (January 2014). "Life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle energy analysis (LCEA) of buildings and the building sector: A review". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 29: 394–416. Bibcode:2014RSERv..29..394C. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.08.037.

- ^ Richards, Bryce S.; Watt, Muriel E. (January 2005). "Permanently dispelling a myth of photovoltaics via the adoption of a new net energy indicator". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 11: 162–172. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2004.09.015.

- ^ Dale, Michael; Benson, Sally M. (2013). "Energy Balance of the Global Photovoltaic (PV) Industry - Is the PV Industry a Net Electricity Producer?". Environmental Science & Technology. 47 (7): 3482–3489. Bibcode:2013EnST...47.3482D. doi:10.1021/es3038824. PMID 23441588.

- ^ Tian, Xueyu; Stranks, Samuel D.; You, Fengqi (31 July 2020). "Life cycle energy use and environmental implications of high-performance perovskite tandem solar cells". Science Advances. 6 (31) eabb0055. Bibcode:2020SciA....6...55T. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb0055. PMC 7399695. PMID 32789177.

- ^ Gerbinet, Saïcha; Belboom, Sandra; Léonard, Angélique (October 2014). "Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) of photovoltaic panels: A review". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 38: 747–753. Bibcode:2014RSERv..38..747G. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.043.

- ^ Tian, Xueyu; Stranks, Samuel D.; You, Fengqi (September 2021). "Life cycle assessment of recycling strategies for perovskite photovoltaic modules". Nature Sustainability. 4 (9): 821–829. Bibcode:2021NatSu...4..821T. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00737-z.

- ^ McManus, M.C. (October 2010). "Life cycle impacts of waste wood biomass heating systems: A case study of three UK based systems". Energy. 35 (10): 4064–4070. Bibcode:2010Ene....35.4064M. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2010.06.014.

- ^ Allen, S. R.; Hammond, G. P.; Harajli, H. A.; Jones, C. I.; McManus, M. C.; Winnett, A. B. (May 2008). "Integrated appraisal of micro-generators: methods and applications". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Energy. 161 (2): 73–86. Bibcode:2008ICEE..161...73A. doi:10.1680/ener.2008.161.2.73.

- ^ Damgaard, Anders; Riber, Christian; Fruergaard, Thilde; Hulgaard, Tore; Christensen, Thomas H. (July 2010). "Life-cycle-assessment of the historical development of air pollution control and energy recovery in waste incineration" (PDF). Waste Management. 30 (7): 1244–1250. Bibcode:2010WaMan..30.1244D. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2010.03.025. PMID 20378326.

- ^ Liamsanguan, Chalita; Gheewala, Shabbir H. (April 2008). "LCA: A decision support tool for environmental assessment of MSW management systems". Journal of Environmental Management. 87 (1): 132–138. Bibcode:2008JEnvM..87..132L. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.01.003. PMID 17350748.

- ^ Kerr, Niall; Gouldson, Andy; Barrett, John (July 2017). "The rationale for energy efficiency policy: Assessing the recognition of the multiple benefits of energy efficiency retrofit policy". Energy Policy. 106: 212–221. Bibcode:2017EnPol.106..212K. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.053. hdl:20.500.11820/b78583fe-7f05-4c05-ad27-af5135a07e3e.

- ^ Hammond, Geoffrey P. (10 May 2004). "Engineering sustainability: thermodynamics, energy systems, and the environment". International Journal of Energy Research. 28 (7): 613–639. Bibcode:2004IJER...28..613H. doi:10.1002/er.988.

- ^ Pehnt, Martin (2006). "Dynamic life cycle assessment (LCA) of renewable energy technologies". Renewable Energy. 31 (1): 55–71. Bibcode:2006REne...31...55P. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2005.03.002.

- ^ Pehnt, Martin (2003). "Assessing future energy and transport systems: the case of fuel cells". The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 8 (5) 283: 283–289. Bibcode:2003IJLCA...8..283P. doi:10.1007/BF02978920.

- ^ J.M. Pearce, "Optimizing Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Strategies to Suppress Energy Cannibalism" Archived 14 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine 2nd Climate Change Technology Conference Proceedings, p. 48, 2009

- ^ Joshua M. Pearce (2008). "Thermodynamic limitations to nuclear energy deployment as a greenhouse gas mitigation technology" (PDF). International Journal of Nuclear Governance, Economy and Ecology. 2 (1) 17358: 113–130. doi:10.1504/IJNGEE.2008.017358.