Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Hominoids Apes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Parvorder: | Catarrhini |

| Superfamily: | Hominoidea Gray, 1825[1] |

| Type species | |

| Homo sapiens | |

| Families | |

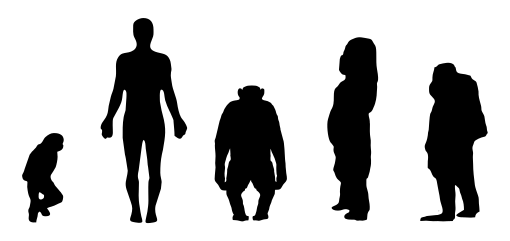

Apes, collectively Hominoidea (/ˌhɒmɪˈnɔɪdi.ə/), are a superfamily of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and Europe in prehistory, and counting humans are found globally). Apes are more closely related to Old World monkeys (family Cercopithecidae) than to the New World monkeys (Platyrrhini) with both Old World monkeys and apes placed in the clade Catarrhini. Apes do not have tails due to a mutation of the TBXT gene.[2][3] In traditional and non-scientific use, the term ape can include tailless primates taxonomically considered Cercopithecidae (such as the Barbary ape and black ape), and is thus not equivalent to the scientific taxon Hominoidea. There are two extant branches of the superfamily Hominoidea: the gibbons, or lesser apes; and the hominids, or great apes.

- The family Hylobatidae, the lesser apes, include four genera and a total of 20 species of gibbon, including the lar gibbon and the siamang, all native to Asia. They are highly arboreal and bipedal on the ground. They have lighter bodies and smaller social groups than great apes.

- The family Hominidae (hominids), the great apes, includes four genera comprising three extant species of orangutans, two extant species of gorillas, two extant species of chimpanzees, and humans.[a][4][5][6]

Except for gorillas and humans, hominoids are agile climbers of trees. Apes eat a variety of plant and animal foods, with the majority of food being plant foods, which can include fruits, leaves, stalks, roots and seeds, including nuts and grass seeds. Human diets are sometimes substantially different from that of other hominoids due in part to the development of technology and a wide range of habitation.

All extant non-human hominoids are rare and threatened with extinction. The main threat is habitat loss, though some populations are further imperiled by hunting. The great apes of Africa are also facing threat from the Ebola virus.[7]

Name and terminology

[edit]−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Ape", from Old English apa, is a word of uncertain origin.[b] The term has a history of rather imprecise usage—and of comedic or punning usage in the vernacular. Its earliest meaning was generally of any non-human anthropoid primate, as is still the case for its cognates in other Germanic languages.[c][8] Later, after the term "monkey" had been introduced into English, "ape" was specialized to refer to a tailless (therefore exceptionally human-like) primate.[9] Thus, the term "ape" obtained two different meanings, as shown in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica entry: it could be used as a synonym for "monkey" and it could denote the tailless human-like primate in particular.[10]

Some, or recently all, hominoids are also called "apes", but the term is used broadly and has several different senses within both popular and scientific settings. "Ape" has been used as a synonym for "monkey" or for naming any primate with a human-like appearance, particularly those without a tail.[10] Biologists have traditionally used the term "ape" to mean a member of the superfamily Hominoidea other than humans,[4] but more recently to mean all members of Hominoidea. So "ape"—not to be confused with "great ape"—now becomes another word for hominoid including humans.[6][d]

The taxonomic term hominoid is derived from, and intended as encompassing, the hominids, the family of great apes. Both terms were introduced by Gray (1825).[11] The term hominins is also due to Gray (1824), intended as including the human lineage (see also Hominidae#Terminology, Human taxonomy).

The distinction between apes and monkeys is complicated by the traditional paraphyly of monkeys: Apes emerged as a sister group of Old World Monkeys in the catarrhines, which are a sister group of New World Monkeys. Therefore, cladistically, apes, catarrhines and related contemporary extinct groups such as Parapithecidae are monkeys as well, for any consistent definition of "monkey". "Old World monkey" may also legitimately be taken to be meant to include all the catarrhines, including apes and extinct species such as Aegyptopithecus,[12][13][14][15] in which case the apes, Cercopithecoidea and Aegyptopithecus emerged within the Old World monkeys.

The primates called "apes" today became known to Europeans after the 18th century. As zoological knowledge developed, it became clear that taillessness occurred in a number of different and otherwise distantly related species. Sir Wilfrid Le Gros Clark was one of those primatologists who developed the idea that there were trends in primate evolution and that the extant members of the order could be arranged in an "ascending series", leading from "monkeys" to "apes" to humans. Within this tradition "ape" came to refer to all members of the superfamily Hominoidea except humans.[4] As such, this use of "apes" represented a paraphyletic grouping, meaning that, even though all species of apes were descended from a common ancestor, this grouping did not include all the descendant species, because humans were excluded from being among the apes.[e]

Traditionally, the English-language vernacular name "apes" does not include humans, but phylogenetically, humans (Homo) form part of the family Hominidae within Hominoidea. Thus, there are at least three common, or traditional, uses of the term "ape": non-specialists may not distinguish between "monkeys" and "apes", that is, they may use the two terms interchangeably; or they may use "ape" for any tailless monkey or non-human hominoid; or they may use the term "ape" to just mean the non-human hominoids.

Modern taxonomy aims for the use of monophyletic groups for taxonomic classification;[16][f] Some literature may now use the common name "ape" to mean all members of the superfamily Hominoidea, including humans. For example, in his 2005 book, Benton wrote "The apes, Hominoidea, today include the gibbons and orang-utan ... the gorilla and chimpanzee ... and humans".[6] Modern biologists and primatologists refer to apes that are not human as "non-human" apes. Scientists broadly, other than paleoanthropologists, may use the term "hominin" to identify the human clade, replacing the term "hominid". See terminology of primate names.

See below, History of hominoid taxonomy, for a discussion of changes in scientific classification and terminology regarding hominoids.

Evolution

[edit]Although the hominoid fossil record is still incomplete and fragmentary, there is now enough evidence to provide an outline of the evolutionary history of humans. Previously, the divergence between humans and other extant hominoids was thought to have occurred 15 to 20 million years ago, and several species of that time period, such as Ramapithecus, were once thought to be hominins and possible ancestors of humans. But, later fossil finds indicated that Ramapithecus was more closely related to the orangutan; and new biochemical evidence indicates that the last common ancestor of humans and non-hominins (that is, the chimpanzees) occurred between 5 and 10 million years ago, and probably nearer the lower end of that range (more recent); see Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor (CHLCA).

Taxonomic classification and phylogeny

[edit]Genetic analysis combined with fossil evidence indicates that hominoids diverged from the Old World monkeys about 25 million years ago (mya), near the Oligocene–Miocene boundary.[17][18][19] The gibbons split from the rest about 18 mya, and the hominid splits happened 14 mya (Pongo),[20] 7 mya (Gorilla), and 3–5 mya (Homo & Pan).[21] In 2015, a new genus and species were described, Pliobates cataloniae, which lived 11.6 mya, and appears to predate the split between Hominidae and Hylobatidae.[22][23][24][6][clarification needed]

| Crown Catharrhini (31) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catarrhini (31.0 Mya) |

| |||||||

The families, and extant genera and species of hominoids are:

- Superfamily Hominoidea[25]

- Family Hominidae: hominids ("great apes")

- Genus Pongo: orangutans

- Bornean orangutan, P. pygmaeus

- Sumatran orangutan, P. abelii

- Tapanuli orangutan, P. tapanuliensis[26]

- Genus Gorilla: gorillas

- Western gorilla, G. gorilla

- Eastern gorilla, G. beringei

- Genus Homo: humans

- Human, H. sapiens

- Genus Pan: chimpanzees

- Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes

- Bonobo, P. paniscus

- Genus Pongo: orangutans

- Family Hylobatidae: gibbons ("lesser apes")

- Genus Hylobates

- Lar gibbon or white-handed gibbon, H. lar

- Bornean white-bearded gibbon, H. albibarbis

- Agile gibbon or black-handed gibbon, H. agilis

- Western grey gibbon or Abbott's grey gibbon, H. abbotti[27]

- Eastern grey gibbon or northern grey gibbon, H. funereus[27]

- Müller's gibbon or southern grey gibbon, H. muelleri

- Silvery gibbon, H. moloch

- Pileated gibbon or capped gibbon, H. pileatus

- Kloss's gibbon or Mentawai gibbon or bilou, H. klossii

- Genus Hoolock

- Western hoolock gibbon, H. hoolock

- Eastern hoolock gibbon, H. leuconedys

- Skywalker hoolock gibbon, H. tianxing

- Genus Symphalangus

- Siamang, S. syndactylus

- Genus Nomascus

- Northern buffed-cheeked gibbon, N. annamensis

- Black crested gibbon, N. concolor

- Eastern black crested gibbon, N. nasutus

- Hainan black crested gibbon, N. hainanus

- Southern white-cheeked gibbon N. siki

- White-cheeked crested gibbon, N. leucogenys

- Yellow-cheeked gibbon, N. gabriellae

- Genus Hylobates

- Family Hominidae: hominids ("great apes")

History of hominoid taxonomy

[edit]The history of hominoid taxonomy is complex and somewhat confusing. Recent evidence has changed our understanding of the relationships between the hominoids, especially regarding the human lineage; and the traditionally used terms have become somewhat confused. Competing approaches to methodology and terminology are found among current scientific sources. Over time, authorities have changed the names and the meanings of names of groups and subgroups as new evidence — that is, new discoveries of fossils and tools and of observations in the field, plus continual comparisons of anatomy and DNA sequences — has changed the understanding of relationships between hominoids. There has been a gradual demotion of humans from being 'special' in the taxonomy to being one branch among many. This recent turmoil (of history) illustrates the growing influence on all taxonomy of cladistics, the science of classifying living things strictly according to their lines of descent.[citation needed]

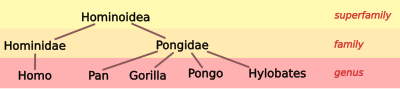

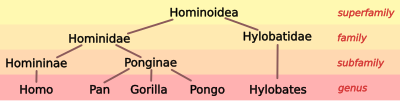

Today, there are eight extant genera of hominoids. They are the four genera in the family Hominidae, namely Homo, Pan, Gorilla, and Pongo; plus four genera in the family Hylobatidae (gibbons): Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus and Symphalangus.[25] (The two subspecies of hoolock gibbons were recently moved from the genus Bunopithecus to the new genus Hoolock and re-ranked as species; a third species was described in January 2017).[28]

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus, relying on second- or third-hand accounts, placed a second species in Homo along with H. sapiens: Homo troglodytes ("cave-dwelling man"). Although the term "Orang Outang" is listed as a variety – Homo sylvestris – under this species, it is nevertheless not clear to which animal this name refers, as Linnaeus had no specimen to refer to, hence no precise description. Linnaeus may have based Homo troglodytes on reports of mythical creatures, then-unidentified simians, or Asian natives dressed in animal skins.[29] Linnaeus named the orangutan Simia satyrus ("satyr monkey"). He placed the three genera Homo, Simia and Lemur in the order of Primates.

The troglodytes name was used for the chimpanzee by Blumenbach in 1775, but moved to the genus Simia. The orangutan was moved to the genus Pongo in 1799 by Lacépède.

Linnaeus's inclusion of humans in the primates with monkeys and apes was troubling for people who denied a close relationship between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom. Linnaeus's Lutheran archbishop had accused him of "impiety". In a letter to Johann Georg Gmelin dated 25 February 1747, Linnaeus wrote:

It is not pleasing to me that I must place humans among the primates, but man is intimately familiar with himself. Let's not quibble over words. It will be the same to me whatever name is applied. But I desperately seek from you and from the whole world a general difference between men and simians from the principles of Natural History. I certainly know of none. If only someone might tell me one! If I called man a simian or vice versa I would bring together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to, in accordance with the law of Natural History.[30]

Accordingly, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the first edition of his Manual of Natural History (1779), proposed that the primates be divided into the Quadrumana (four-handed, i.e. apes and monkeys) and Bimana (two-handed, i.e. humans). This distinction was taken up by other naturalists, most notably Georges Cuvier. Some elevated the distinction to the level of order.

However, the many affinities between humans and other primates – and especially the "great apes" – made it clear that the distinction made no scientific sense. In his 1871 book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Charles Darwin wrote:

The greater number of naturalists who have taken into consideration the whole structure of man, including his mental faculties, have followed Blumenbach and Cuvier, and have placed man in a separate Order, under the title of the Bimana, and therefore on an equality with the orders of the Quadrumana, Carnivora, etc. Recently many of our best naturalists have recurred to the view first propounded by Linnaeus, so remarkable for his sagacity, and have placed man in the same Order with the Quadrumana, under the title of the Primates. The justice of this conclusion will be admitted: for in the first place, we must bear in mind the comparative insignificance for classification of the great development of the brain in man, and that the strongly marked differences between the skulls of man and the Quadrumana (lately insisted upon by Bischoff, Aeby, and others) apparently follow from their differently developed brains. In the second place, we must remember that nearly all the other and more important differences between man and the Quadrumana are manifestly adaptive in their nature, and relate chiefly to the erect position of man; such as the structure of his hand, foot, and pelvis, the curvature of his spine, and the position of his head.[31]

Changes in taxonomy and terminology

[edit]| Humans the non-apes: Until about 1960, taxonomists typically divided the superfamily Hominoidea into two families. The science community treated humans and their extinct relatives as the outgroup within the superfamily; that is, humans were considered as quite distant from kinship with the "apes". Humans were classified as the family Hominidae and were known as the "hominids". All other hominoids were known as "apes" and were referred to the family Pongidae.[32] |

|

| The "great apes" in Pongidae: The 1960s saw the methodologies of molecular biology applied to primate taxonomy. Goodman's 1964 immunological study of serum proteins led to re-classifying the hominoids into three families: the humans in Hominidae; the great apes in Pongidae; and the "lesser apes" (gibbons) in Hylobatidae.[33] However, this arrangement had two trichotomies: Pan, Gorilla, and Pongo of the "great apes" in Pongidae, and Hominidae, Pongidae, and Hylobatidae in Hominoidea. These presented a puzzle; scientists wanted to know which genus speciated first from the common hominoid ancestor. |

|

| Gibbons the outgroup: New studies indicated that gibbons, not humans, are the outgroup within the superfamily Hominoidea, meaning: the rest of the hominoids are more closely related to each other than (any of them) are to the gibbons. With this splitting, the gibbons (Hylobates, et al.) were isolated after moving the great apes into the same family as humans. Now the term "hominid" encompassed a larger collective taxa within the family Hominidae. With the family trichotomy settled, scientists could now work to learn which genus is 'least' related to the others in the subfamily Ponginae. |

|

| Orangutans the outgroup: Investigations comparing humans and the three other hominid genera disclosed that the African apes (chimpanzees and gorillas) and humans are more closely related to each other than any of them are to the Asian orangutans (Pongo); that is, the orangutans, not humans, are the outgroup within the family Hominidae. This led to reassigning the African apes to the subfamily Homininae with humans—which presented a new three-way split: Homo, Pan, and Gorilla.[34] |

|

| Hominins: In an effort to resolve the trichotomy, while preserving the nostalgic "outgroup" status of humans, the subfamily Homininae was divided into two tribes: Gorillini, comprising genus Pan and genus Gorilla; and Hominini, comprising genus Homo (the humans). Humans and close relatives now began to be known as "hominins", that is, of the tribe Hominini. Thus, the term "hominin" succeeded to the previous use of "hominid", which meaning had changed with changes in Hominidae (see above: 3rd graphic, "Gibbons the outgroup"). |

|

| Gorillas the outgroup: New DNA comparisons now provided evidence that gorillas, not humans, are the outgroup in the subfamily Homininae; this suggested that chimpanzees should be grouped with humans in the tribe Hominini, but in separate subtribes.[35] Now the name "hominin" delineated Homo plus those earliest Homo relatives and ancestors that arose after the divergence from the chimpanzees. (Humans are no longer recognized as an outgroup, but are a branch, deep in the tree of the pre-1960s ape group). |

|

| Speciation of gibbons: Later DNA comparisons disclosed previously unknown speciation of genus Hylobates (gibbons) into four genera: Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus, and Symphalangus.[25][28] The ordering of speciation of these four genera are being investigated as of 2022[update]. |

|

Characteristics

[edit]

The lesser apes are the gibbon family, Hylobatidae, of sixteen species; all are native to Asia. Their major differentiating characteristic is their long arms, which they use to brachiate through trees. Their wrists are ball and socket joints as an evolutionary adaptation to their arboreal lifestyle. Generally smaller than the African apes, the largest gibbon, the siamang, weighs up to 14 kg (31 lb); in comparison, the smallest "great ape", the bonobo, is 34 to 60 kg (75 to 132 lb).

The superfamily Hominoidea falls within the parvorder Catarrhini, which also includes the Old World monkeys of Africa and Eurasia. Within this grouping, the two families Hylobatidae and Hominidae can be distinguished from Old World monkeys by the number of cusps on their molars; hominoids have five in the "Y-5" molar pattern, whereas Old World monkeys have only four in a bilophodont pattern.

Further, in comparison with Old World monkeys, hominoids are noted for: more mobile shoulder joints and arms due to the dorsal position of the scapula; broader ribcages that are flatter front-to-back; and a shorter, less mobile spine, with greatly reduced caudal (tail) vertebrae—resulting in complete loss of the tail in extant hominoid species. These are anatomical adaptations, first, to vertical hanging and swinging locomotion (brachiation) and, later, to developing balance in a bipedal pose. Note there are primates in other families that also lack tails, and at least one, the pig-tailed langur, is known to walk significant distances bipedally. The front of the ape skull is characterised by its sinuses, fusion of the frontal bone, and by post-orbital constriction.

Distinction from monkeys

[edit]Cladistically, apes, catarrhines, and extinct species such as Aegyptopithecus and Parapithecidaea, are monkeys,[citation needed] so one can only specify ape features not present in other monkeys.

Unlike most monkeys, apes do not possess a tail. Monkeys are more likely to be in trees and use their tails for balance. While the great apes are considerably larger than monkeys, gibbons (lesser apes) are smaller than some monkeys. Apes are considered to be more intelligent than monkeys, which are considered to have more primitive brains.[36]

The enzyme urate oxidase has become inactive in all apes, its function having been lost in two primate lineages during the middle Miocene; first in the common ancestors of Hominidae, and later in the common ancestor of Hylobatidae. It has been hypothesized that in both incidents it was a mutation that occurred in apes living in Europe when the climate was getting colder, leading to starvation during winter. The mutation changed the biochemistry of the apes and made it easier to accumulate fat, which allowed the animals to survive longer periods of starvation. When they migrated to Asia and Africa, this genetic trait remained.[37][38]

Behaviour

[edit]Major studies of behaviour in the field were completed on the three better-known "great apes", for example by Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birutė Galdikas. These studies have shown that in their natural environments, the non-human hominoids show sharply varying social structure: gibbons are monogamous, territorial pair-bonders, orangutans are solitary, gorillas live in small troops with a single adult male leader, while chimpanzees live in larger troops with bonobos exhibiting promiscuous sexual behaviour. Their diets also vary; gorillas are foliovores, while the others are all primarily frugivores, although the common chimpanzee hunts for meat. Foraging behaviour is correspondingly variable.

In November 2023, scientists reported, for the first time, evidence that groups of primates, including apes, and, particularly bonobos, are capable of cooperating with each other.[39][40]

Diet

[edit]Apart from humans and gorillas, apes eat a predominantly frugivorous diet, mostly fruit, but supplemented with a variety of other foods. Gorillas are predominantly folivorous, eating mostly stalks, shoots, roots and leaves with some fruit and other foods. Non-human apes usually eat a small amount of raw animal foods such as insects or eggs. In the case of humans, migration and the invention of hunting tools and cooking has led to an even wider variety of foods and diets, with many human diets including large amounts of cooked tubers (roots) or legumes.[41] Other food production and processing methods including animal husbandry and industrial refining and processing have further changed human diets.[42] Humans and other apes occasionally eat other primates.[43] Some of these primates are now close to extinction with habitat loss being the underlying cause.[44][45]

Cognition

[edit]

All the non-human hominoids are generally thought of as highly intelligent, and scientific study has broadly confirmed that they perform very well on a wide range of cognitive tests—though there is relatively little data on gibbon cognition. The early studies by Wolfgang Köhler demonstrated exceptional problem-solving abilities in chimpanzees, which Köhler attributed to insight. The use of tools has been repeatedly demonstrated; more recently, the manufacture of tools has been documented, both in the wild and in laboratory tests. Imitation is much more easily demonstrated in "great apes" than in other primate species. Almost all the studies in animal language acquisition have been done with "great apes", and though there is continuing dispute as to whether they demonstrate real language abilities, there is no doubt that they involve significant feats of learning. Chimpanzees in different parts of Africa have developed tools that are used in food acquisition, demonstrating a form of animal culture.[46]

Threats and conservation

[edit]All non-human hominoids are rare and threatened with extinction. The eastern hoolock gibbon is the least threatened, only being vulnerable to extinction. Five gibbon species are critically endangered, as are all species of orangutan and gorilla. The remaining species of gibbon, the bonobo, and all four subspecies of chimpanzees are endangered. The chief threat to most of the endangered species is loss of tropical rainforest habitat, though some populations are further imperiled by hunting for bushmeat. The great apes of Africa are also facing threat from the Ebola virus.[47] Currently considered to be the greatest threat to survival of African apes, Ebola infection is responsible for the death of at least one third of all gorillas and chimpanzees since 1990.[48]

All the species of great apes in Africa are considered endangered. Hunting, logging, agricultural expansion and mining are among the main threats.[49]

See also

[edit] Mammals portal

Mammals portal- Great Ape Project

- Great Apes Survival Partnership

- International Primate Day

- Kinshasa Declaration on Great Apes

- List of individual apes (for notable non-fictional non-human apes)

- List of primates by population

Notes

[edit]- ^ Although Dawkins is clear that he uses "apes" for Hominoidea, he also uses "great apes" in ways which exclude humans. Thus in Dawkins 2005: "Long before people thought in terms of evolution ... great apes were often confused with humans" (p. 114); "gibbons are faithfully monogamous, unlike the great apes which are our closer relatives" (p. 126).

- ^ The hypothetical Proto-Germanic form is given as *apōn (F. Kluge, Etymologisches Wörterbuch der Deutschen Sprache (2002), online version, s.v. "Affe"; V. Orel, A handbook of Germanic etymology (2003), s.v. "*apōn" or as *apa(n) (Online Etymology Dictionary (2001–2014), s.v. "ape"; M. Philippa, F. Debrabandere, A. Quak, T. Schoonheim & N. van der Sijs, Etymologisch woordenboek van het Nederlands (2003–2009), s.v. "aap"). Perhaps ultimately derived from a non-Indo-European language, the word might be a direct borrowing from Celtic, or perhaps from Slavic, although in both cases it is also argued that the borrowing, if it took place, went in the opposite direction.

- ^ "Any simian known on the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages; monkey or ape"; cf. ape-ward: "a juggler who keeps a trained monkey for the amusement of the crowd." (Middle English Dictionary, s.v. "ape").

- ^ Dawkins 2005; for example "[a]ll apes except humans are hairy" (p. 99), "[a]mong the apes, gibbons are second only to humans" (p. 126).

- ^ Definitions of paraphyly vary; for the one used here see e.g. Stace 2010, pp. 106

- ^ Definitions of monophyly vary; for the one used here see e.g. Mishler 2009, pp. 114

References

[edit]- ^ Gray, J. E. "An outline of an attempt at the disposition of Mammalia into tribes and families, with a list of the genera apparently appertaining to each tribe". Annals of Philosophy. New Series. 10: 337–344. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Xia, Bo; Zhang, Weimin; Wudzinska, Aleksandra; Huang, Emily; Brosh, Ran; Pour, Maayan; Miller, Alexander; Dasen, Jeremy S.; Maurano, Matthew T.; Kim, Sang Y.; Boeke, Jef D. (16 September 2021). "The genetic basis of tail-loss evolution in humans and apes". bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.09.14.460388.

- ^ Weisberger, Mindy (23 March 2024). "Why don't humans have tails? Scientists find answers in an unlikely place". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Dixson 1981, pp. 13.

- ^ Grehan, J. R. (2006). "Mona Lisa smile: the morphological enigma of human and great ape evolution". Anatomical Record. 289B (4): 139–157. doi:10.1002/ar.b.20107. PMID 16865704.

- ^ a b c d Benton, M. J. (2005). Vertebrate Palaeontology. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2011., p. 371

- ^ Rush, J. (23 January 2015). "Ebola virus 'has killed a third of world's gorillas and chimpanzees' – and could pose greatest threat to their survival, conservationists warn". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Terry 1977, pp. 3.

- ^ Terry 1977, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 160.

- ^ Gray, JE. "An outline of an attempt at the disposition of Mammalia into tribes and families, with a list of the genera apparently appertaining to each tribe". Annals of Philosophy. New Series. 10: 337–344. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Osman Hill, W. C. (1953). Primates Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy I—Strepsirhini. Edinburgh Univ Pubs Science & Maths, No 3. Edinburgh University Press. p. 53. OCLC 500576914.

- ^ Martin, W. C. L. (1841). A General Introduction to the Natural History of Mammiferous Animals, With a Particular View of the Physical History of man, and the More Closely Allied Genera of the Order Quadrumana, or Monkeys. London: Wright and Co. printers. pp. 340, 361.

- ^ Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, M. É. (1812). "Tableau des quadrumanes, ou des animaux composant le premier ordre de la classe des Mammifères". Annales du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle. 19. Paris: 85–122. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Bugge, J. (1974). "Chapter 4". Cells Tissues Organs. 87 (Suppl. 62): 32–43. doi:10.1159/000144209. ISSN 1422-6405.

- ^ Springer; D. H. (1 July 2011). An Introduction to Zoology: Investigating the Animal World. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 536. ISBN 978-0-7637-5286-6.

Through careful study taxonomists today struggle to eliminate polyphyletic and paraphyletic groups and taxons, reclassifying their members into appropriate monophyletic taxa

- ^ "Fossils may pinpoint critical split between apes and monkeys". 15 May 2013. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Rossie, J. B.; Hill, A. (2018). "A new species of Simiolus from the middle Miocene of the Tugen Hills, Kenya". Journal of Human Evolution. 125: 50–58. Bibcode:2018JHumE.125...50R. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.09.002. PMID 30502897. S2CID 54625375.

- ^ Rasmussen, D. T.; Friscia, A. R.; Gutierrez, M.; et al. (2019). "Primitive Old World monkey from the earliest Miocene of Kenya and the evolution of cercopithecoid bilophodonty". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (13): 6051–6056. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.6051R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1815423116. PMC 6442627. PMID 30858323.

- ^ Alba, D. M.; Fortuny, J.; Moyà-Solà, S. (2010). "Enamel thickness in the Middle Miocene great apes Anoiapithecus, Pierolapithecus and Dryopithecus". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1691): 2237–2245. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0218. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2880156. PMID 20335211.

- ^ Grabowski, M.; Jungers, W. L. (2017). "Evidence of a chimpanzee-sized ancestor of humans but a gibbon-sized ancestor of apes". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 880. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..880G. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00997-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5638852. PMID 29026075.

- ^ "A new primate species at the root of the tree of extant hominoids". 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Nengo, I.; Tafforeau, P.; Gilbert, C. C.; et al. (2017). "New infant cranium from the African Miocene sheds light on ape evolution" (PDF). Nature. 548 (7666): 169–174. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..169N. doi:10.1038/nature23456. PMID 28796200. S2CID 4397839. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Dixson 1981, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 178–184. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Cochrane, J. (2 November 2017). "New Orangutan Species Could Be the Most Endangered Great Ape". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ a b Wilson, Don E.; Cavallini, Paolo (2013). Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-96553-89-7. OCLC 1222638259.

- ^ a b Mootnick, A.; Groves, C. P. (2005). "A new generic name for the hoolock gibbon (Hylobatidae)". International Journal of Primatology. 26 (4): 971–976. doi:10.1007/s10764-005-5332-4. S2CID 8394136.

- ^ Frängsmyr, T.; Lindroth, S.; Eriksson, G.; Broberg, G. (1983). Linnaeus, the man and his work. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-7112-1841-3., p. 166

- ^ "Letter, Carl Linnaeus to Johann Georg Gmelin. Uppsala, Sweden, 25 February 1747". Swedish Linnaean Society. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-7607-7814-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ G. G., Simpson (1945). "The principles of classification and a classification of mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 85: 1–350.

- ^ Goodman, M. (1964). "Man's place in the phylogeny of the primates as reflected in serum proteins". In Washburn, S. L. (ed.). Classification and Human Evolution. Chicago: Aldine. pp. 204–234.

- ^ Goodman, M. (1974). "Biochemical evidence on hominid phylogeny". Annual Review of Anthropology. 3 (1): 203–228. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.03.100174.001223.

- ^ Goodman, M.; Tagle, D. A.; Fitch, D. H.; et al. (1990). "Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 30 (3): 260–266. Bibcode:1990JMolE..30..260G. doi:10.1007/BF02099995. PMID 2109087. S2CID 2112935.

- ^ Call, J.; Tomasello, M. (2007). The Gestural Communication of Apes and Monkeys. Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ Johnson, R. J.; Lanaspa, M. A.; Gaucher, E. A. (2011). "Uric acid: A Danger Signal from the RNA World that may have a role in the Epidemic of Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome and CardioRenal Disease: Evolutionary Considerations". Seminars in Nephrology. 31 (5): 394–399. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.08.002. PMC 3203212. PMID 22000645.

- ^ Johnson, Richard J.; Andrews, Peter (2015). "The Fat Gene". Scientific American. 313 (4): 64–69. Bibcode:2015SciAm.313d..64J. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1015-64.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (16 November 2023). "Scientists Find First Evidence That Groups of Apes Cooperate - Some bonobos are challenging the notion that humans are the only primates capable of group-to-group alliances". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Samuni, Liran; et al. (16 November 2023). "Cooperation across social borders in bonobos". Science. 382 (6672): 805–809. Bibcode:2023Sci...382..805S. doi:10.1126/science.adg0844. PMID 37972165. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Lawton, G. (2 November 2016). "Every human culture includes cooking – this is how it began". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Hoag, Hannah (2 December 2013). "Humans are becoming more carnivorous". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.14282. S2CID 183143537. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ Callaway, E. (13 October 2006). "Loving bonobos have a carnivorous dark side". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ M., Michael. "Chimpanzees over-hunt monkey prey almost to extinction". BBC Earth. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Extinction threat to monkeys and other primates due to habitat loss, hunting". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ McGrew, W. (1992). Chimpanzee Material Culture: Implications for Human Evolution.

- ^ Rush, J. (23 January 2015). "Ebola virus 'has killed a third of world's gorillas and chimpanzees' – and could pose greatest threat to their survival, conservationists warn". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Rush, J. (23 January 2015). "Ebola virus 'has killed a third of world's gorillas and chimpanzees' – and could pose greatest threat to their survival, conservationists warn". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Junker, Jessica; Quoss, Luise; Valdez, Jose; Arandjelovic, Mimi; Barrie, Abdulai; Campbell, Geneviève; Heinicke, Stefanie; Humle, Tatyana; Kouakou, Célestin Y.; Kühl, Hjalmar S.; Ordaz-Németh, Isabel; Pereira, Henrique M.; Rainer, Helga; Refisch, Johannes; Sonter, Laura; Sop, Tenekwetche (3 April 2024). "Threat of mining to African great apes". Science Advances. 10 (14). Bibcode:2024SciA...10L.335J. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adl0335. PMC 10990274. PMID 38569032. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

Literature cited

[edit]- Dawkins, R. (2005). The Ancestor's Tale (p/b ed.). London: Phoenix (Orion Books). ISBN 978-0-7538-1996-8.

- Dixson, A. F. (1981). The Natural History of the Gorilla. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-77895-0.

- Mishler, Brent D (2009). "Species are not uniquely real biological entities". In Ayala, F. J. & Arp, R. (eds.). Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Biology. pp. 110–122. doi:10.1002/9781444314922.ch6. ISBN 978-1-4443-1492-2.

- Stace, C. A. (2010). "Classification by molecules: what's in it for field botanists?" (PDF). Watsonia. 28: 103–122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Terry, M. W. (1977). "Use of common and scientific nomenclature to designate laboratory primates". In Schrier, A. M. (ed.). Behavioral Primatology: Advances in Research and Theory. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, N.J., US: Lawrence Erlbaum.

External links

[edit] Data related to Hominoidea at Wikispecies

Data related to Hominoidea at Wikispecies Hominoidea at Wikibooks

Hominoidea at Wikibooks- Pilbeam D. (September 2000). "Hominoid systematics: The soft evidence". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (20): 10684–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710684P. doi:10.1073/pnas.210390497. PMC 34045. PMID 10995486. Agreement between cladograms based on molecular and anatomical data.

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

Terminology and Etymology

Definition and Scope

Apes constitute the superfamily Hominoidea within the suborder Catarrhini of Old World primates, distinguished by the absence of an external tail, broad noses, and adaptations for brachiation and suspensory locomotion.[9] This superfamily encompasses two families: Hylobatidae, comprising the lesser apes such as gibbons and siamangs, which are smaller-bodied and highly arboreal; and Hominidae, which includes the great apes—orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos—and humans.[10] Lesser apes typically weigh 5–12 kg and exhibit lighter builds suited to agile swinging through forest canopies, whereas great apes range from 30–180 kg with more robust frames supporting knuckle-walking or upright postures in some species.[11] Biologically, humans belong to Hominidae and share a most recent common ancestor with other great apes approximately 5–7 million years ago, rendering the vernacular category "apes" paraphyletic when humans are excluded, as it omits a descendant clade without capturing the full monophyletic group.[12] This exclusion persists in common usage to differentiate humans from non-human hominoids, despite phylogenetic evidence confirming humans as apes under a cladistic definition.[13] The term thus scopes non-human members of Hominoidea, focusing on 20–25 extant species across these families, all endangered due to habitat loss and poaching.[14] Geographically, apes are restricted to tropical and subtropical forests: Hylobatidae and orangutans (Pongo spp.) inhabit Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, Malaysia, and parts of Thailand and Vietnam; while gorillas (Gorilla spp.), chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), and bonobos (Pan paniscus) occupy Central and West Africa, from equatorial rainforests to montane habitats up to 4,000 meters elevation.[15] No apes are native to the Americas or Australia, reflecting their Miocene origins in Eurasia and subsequent dispersal.[4]Historical and Linguistic Origins

The English word "ape" derives from Old English apa, which traces back to Proto-Germanic *apô, denoting a tailless primate and appearing in cognates across Germanic languages such as Old Norse api and Old High German affo.[16] Its ultimate origin remains uncertain, potentially linked to an Indo-European root implying mimicry or imitation, reflecting early observations of apes' behavioral similarities to humans, or possibly onomatopoeic associations with their vocalizations; by the 13th century, compounds like "Martin Halfape" appear in English records, suggesting derogatory connotations of ugliness or brutishness.[16] This Germanic term contrasted with later borrowings for tailed primates, as "monkey" entered English around the 16th century from Low German or Dutch via Romance influences like Old French monne or Italian monno, highlighting a linguistic distinction between tailless "apes" and tailed "monkeys" that persisted in European usage.[17] In ancient Greek texts, the term pithēkos referred to apes or monkeys, often evoking notions of mockery or deformity; Aristotle, in his History of Animals (circa 350 BCE), described the ape (pithēkos) as resembling humans in face and posture but quadrupedal otherwise, positioning it as an intermediate form sharing traits with both humans and other animals, while distinguishing the tailed "monkey" (kēbos) as a variant.[18] Roman authors adopted similar views, with Latin simia (from simus, "snub-nosed") applied to apes for their flat faces and imitative habits, as noted by Pliny the Elder in Natural History (77 CE), where apes were portrayed as cunning mimics prone to vanity and theft.[17] During the medieval period, European bestiaries depicted apes as tailless symbols of sin and the devil—lacking a tail like the fallen Satan—and as grotesque imitators of human folly, reinforcing moral allegories in illuminated manuscripts from the 12th century onward.[19] The 18th-century Linnaean system formalized nomenclature in Systema Naturae (1758), classifying humans (Homo sapiens) alongside ape-like genera such as Simia satyrus (orangutan, evoking mythical satyrs) within the order Primates, prompting Linnaeus to challenge contemporaries by questioning bodily distinctions between humans and apes, though the English "ape" term retained its pre-Linnaean focus on non-human forms. This classification influenced English scientific usage, narrowing "ape" to denote non-human hominoids like chimpanzees and gorillas by the 19th century, amid debates on human-ape continuity sparked by Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859).[20] In the 20th century, taxonomic refinements explicitly excluded humans from "ape" in popular and cladistic contexts to underscore distinctions, as pre-1960 divisions separated Hominoidea into families like Pongidae (great apes excluding humans) from Hominidae (humans), a convention persisting in vernacular science despite molecular evidence later integrating humans phylogenetically. This shift avoided anthropocentric blurring, with "ape" standardizing as non-human tailless primates in encyclopedias and texts by mid-century, reflecting a deliberate terminological boundary amid evolutionary insights.[21]Taxonomy and Phylogeny

Current Classification

Apes constitute the superfamily Hominoidea, divided into two extant families: Hylobatidae (lesser apes) and Hominidae (great apes, excluding humans).[22] The family Hylobatidae comprises four genera—Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus, and Symphalangus—encompassing 19 recognized species of gibbons as of taxonomic revisions accounting for genetic and vocalization data.[23] These species are primarily delineated by differences in morphology (e.g., body size, fur coloration), chromosomal variations, and geographic distribution across Southeast Asian forests. Within Hominidae, the subfamily Ponginae includes the genus Pongo with three species: the Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus), Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii), and Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis), distinguished by genetic divergence, cranial morphology, and habitat isolation on Borneo and Sumatra.[22] The subfamily Gorillinae features the genus Gorilla with two species: the western gorilla (G. gorilla, including subspecies G. g. gorilla and G. g. diehli) and eastern gorilla (G. beringei, including G. b. graueri and G. b. beringei); these are separated by over 1 million years of divergence evidenced in mitochondrial DNA, alongside morphological traits like skull shape and body size, and geographic barriers such as the Congo River.[24] [25] The subfamily Homininae contains the genus Pan with two species: the common chimpanzee (P. troglodytes) and bonobo (P. paniscus), differentiated by genetics (e.g., fixed chromosomal inversions), pelage patterns, and the Congo River as a vicariant barrier.[22] Species and subspecies boundaries in apes are determined through integrated criteria including morphological traits (e.g., skeletal robusticity, dentition), genetic markers (e.g., mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences showing divergence thresholds of 1-2% for species), and allopatric geography, though debates continue on thresholds for gorillas, where some analyses suggest eastern-western splits merit full species status due to reproductive isolation implications, while others emphasize gene flow potential.[26]Phylogenetic Relationships

The superfamily Hominoidea diverged from the superfamily Cercopithecoidea (Old World monkeys) approximately 25–30 million years ago during the Oligocene epoch, marking the basal split within Catarrhini primates based on molecular clock analyses and fossil calibrations.[27] This divergence is supported by phylogenetic reconstructions integrating genomic data, which place the common ancestor of apes and Old World monkeys in Afro-Arabia.[28] Within Hominoidea, the family Hylobatidae (gibbons and siamangs) separated from Hominidae (great apes and humans) around 15–20 million years ago in the early Miocene, as estimated from relaxed molecular clock models calibrated with fossil priors.[29] Hominidae then underwent further branching, with the genus Pongo (orangutans) diverging basally from the lineage leading to African apes and humans approximately 12–16 million years ago.[30] The gorilla lineage (Gorilla) split next, around 8–10 million years ago, followed by the divergence between the genus Pan (chimpanzees and bonobos) and the genus Homo approximately 6–7 million years ago.[31] Cladistic analyses consistently recover Hominidae as monophyletic, with orangutans as the outgroup to a clade comprising gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans; the latter three form the Homininae subfamily, underscoring closer genetic affinity among African apes and humans relative to Asian apes.[32] Humans share about 98.5–98.8% DNA sequence identity with chimpanzees, their closest relatives, but these figures primarily reflect nucleotide substitutions while underemphasizing structural variants, insertions/deletions, and regulatory differences that drive profound functional divergences in morphology, cognition, and behavior.[33][34][35]Historical Developments in Taxonomy

In the 10th edition of Systema Naturae published in 1758, Carl Linnaeus classified apes within the order Primates, placing them under the genus Simia alongside monkeys, while grouping humans as the genus Homo in the same order; this arrangement reflected morphological similarities such as taillessness and upright posture but subordinated apes to humans without recognizing a distinct superfamily for tailless primates.[36] Earlier editions had used the term Anthropomorpha for a broader group including humans, apes, sloths, and bats, emphasizing superficial resemblances to humans, though Linnaeus relied on limited, often second-hand descriptions of ape anatomy.[37] This initial framework treated apes as a heterogeneous assemblage lacking precise delineation from monkeys, prioritizing descriptive traits over phylogenetic inference. By the 19th century, taxonomic separations emerged based on enhanced anatomical studies, with British zoologist John Edward Gray establishing the family Pongidae in 1840 to encompass great apes (Pongo, Gorilla, and later Pan), distinct from the human-exclusive Hominidae; this reflected observations of shared arboreal adaptations but maintained humans in a separate family due to bipedalism and brain size differences.[38] Ernst Haeckel further refined classifications in the 1860s, proposing suborders for catarrhines including apes, yet debates persisted over whether morphological convergences, such as knuckle-walking in African apes, warranted closer human-ape linkage or reinforced separation.[39] Twentieth-century taxonomy grappled with human inclusion amid fossil discoveries like Australopithecus (1924 onward), prompting debates on whether great apes should join Hominidae or remain in Pongidae; morphological cladistics favored exclusion until molecular data intervened.[39] In 1967, Vincent Sarich and Allan Wilson's immunological comparisons of blood proteins introduced molecular clocks, estimating human-chimpanzee divergence at approximately 5 million years ago—closer than chimpanzee-gorilla splits—challenging morphology-based distances and supporting ape monophyly excluding gibbons.[40] These findings fueled revisions, culminating in the 1980s-1990s consensus to dissolve Pongidae and subsumed great apes into Hominidae as subfamilies (e.g., Ponginae for orangutans, Gorillinae, Homininae for humans and African apes), driven by DNA hybridization and sequence data over traditional metrics.[41] Post-2000 genomic advancements refined ape taxonomy, with gibbons formally recognized as the distinct family Hylobatidae since Gray's 1870 proposal but bolstered by molecular phylogenies confirming their early divergence around 15-18 million years ago.[42] Haplotype-resolved genome assemblies in the 2020s, including complete telomere-to-telomere sequences for chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans published in 2024, have validated subspecies boundaries—such as Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii versus P. t. troglodytes—through divergence timing (e.g., human-chimp split at 5.5-6.3 million years ago) and haplotype diversity, shifting emphasis from gross morphology to genetic coalescence and selection pressures.[43] These refinements underscore genetics' superiority in resolving cryptic variation, though morphological data retains utility for fossil integration.[44]Evolutionary History

Fossil Record and Origins

The earliest known hominoids, representing the basal radiation of the ape lineage, appeared in the early Miocene epoch, approximately 23 to 17 million years ago, primarily in East Africa. The genus Proconsul, discovered in sites such as those in Kenya and Uganda, exemplifies these primitive forms, with species like P. africanus and P. heslon exhibiting tailless bodies, a broad thoracic cage, and adaptations for arboreal quadrupedalism combined with suspensory locomotion, such as flexible shoulder joints and long forelimbs.[45][46] These traits mark a departure from cercopithecoid monkeys, though Proconsul retained some primitive features like convergent incisors and lacked the specialized brachiation seen in later apes.[47] By the middle Miocene, around 16 to 11 million years ago, hominoid diversity increased, with taxa dispersing into Eurasia and showing more derived ape-like morphologies. In Europe, Dryopithecus, known from sites in France and Spain dated to about 12.5 to 11.1 million years ago, displayed thin tooth enamel, a Y-5 molar pattern, and postcranial evidence of below-branch suspension, suggesting affinities to the great ape clade.[48] Concurrently, in South Asia, Sivapithecus from the Indian subcontinent, approximately 12.5 to 8.6 million years old, featured a short face and thick molars akin to modern orangutans, supporting its role as an early pongine (Pongo lineage) ancestor.[31] Late Miocene forms, such as Nakalipithecus nakayamai from Kenya around 10 million years ago, further illustrate this diversification, with robust jaws and thick-enameled teeth indicating a great ape-like dietary adaptation to tougher vegetation.[49] The fossil record of non-human great apes becomes markedly sparse from the Pliocene (5.3 to 2.6 million years ago) through the Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), contrasting with the abundance of early hominins like Australopithecus in open habitats. This scarcity stems from the apes' persistence in tropical forest environments, where acidic soils, high humidity, and rapid organic decay hinder fossilization, compounded by geological processes like lixiviation and erosion that destroy potential remains before preservation.[50] Transitional fossils bridging Miocene hominoids to extant great ape genera remain limited, underscoring gaps in the record despite evidence of a last common ancestor with humans around 9 to 6.5 million years ago.[31]Molecular and Genetic Evidence

Molecular analyses employing mitochondrial DNA and nuclear gene sequences, calibrated via molecular clocks, estimate the initial radiation of Hominoidea around 25 million years ago (mya), marking the divergence from cercopithecoids.[51] These clocks account for rate variations across lineages, with nuclear DNA providing more precise calibrations than mitochondrial alone due to reduced saturation effects in deeper divergences.[52] Whole-genome sequencing has further refined great ape splits: orangutans diverged from African apes approximately 12-16 mya, gorillas from the chimpanzee-bonobo-human clade around 8-10 mya, and chimpanzees/bonobos from humans at 5.5-6.3 mya.[43] Advancements in 2025 produced haplotype-resolved, telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies for chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, Bornean and Sumatran orangutans, and siamangs, enabling detailed reconstruction of phased haplotypes without human contamination.[53] These assemblies reveal speciation mechanisms, including recurrent structural variations and recent turnover in loci like 17q21.31, which exhibit inverted haplotypes in chimpanzees relative to gorillas and orangutans.[54] Comparative analyses highlight regulatory variations driving lineage-specific adaptations, such as elevated segmental duplications in chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas—exceeding those in humans—potentially linked to immune and neural traits.[55] Genomic scans of natural selection in great apes identify footprints of adaptation in genes influencing locomotion and skeletal morphology, with African apes showing signatures in loci associated with knuckle-walking via eccentric muscle contractions and wrist stabilization.[56] Gibbons exhibit distinct regulatory enhancements for brachiation, reflected in expanded gene families for tendon strength and shoulder mobility, though independent evolution of locomotor traits underscores homoplasy over shared ancestry in some cases.[57] Endangered populations, including mountain gorillas and Tapanuli orangutans, display critically low genetic diversity—comparable to inbred isolates—with inbreeding coefficients exceeding 0.2 in some groups, elevating risks of deleterious mutations and reduced fitness.[58][59] These patterns, quantified via heterozygosity metrics below 0.001 in bottlenecked lineages, inform conservation by prioritizing gene flow to mitigate load accumulation.[60]Physical Characteristics

Morphology and Anatomy

Apes, or members of the superfamily Hominoidea, are characterized by the absence of an external tail, a feature that sets them apart from Old World monkeys and reflects adaptations to suspensory locomotion rather than quadrupedalism.[4] Their skeletons typically feature relatively short trunks, broad chests, elongated arms relative to legs, and long hands suited for grasping and swinging (brachiation in lesser apes) or knuckle-walking (in great apes).[4] These proportions facilitate arboreal suspension and terrestrial quadrupedalism, with arm lengths often exceeding leg lengths by 10-20% in species like chimpanzees and gorillas.[61] Body sizes vary widely across ape taxa, from the smallest hylobatids (gibbons) weighing 5-12 kg to large great apes like male gorillas exceeding 170 kg, enabling diverse ecological niches from forest canopies to ground foraging.[62] Sexual dimorphism is pronounced, particularly in great apes, where males average 1.5-2 times the body mass of females—e.g., adult male chimpanzees weigh 40-60 kg compared to 30-50 kg for females—linked to intrasexual competition.[63] [64] The dentition follows the catarrhine formula of 2.1.2.3 (two incisors, one canine, two premolars, three molars per quadrant, totaling 32 teeth), with broad incisors and reduced canines relative to body size compared to earlier primates.[62] Great apes possess robust jaws and larger molars adapted for processing tough, fibrous vegetation, though dental wear patterns vary by diet.[4] Sensory anatomy emphasizes vision over olfaction: forward-facing eyes provide stereoscopic depth perception essential for navigating complex three-dimensional environments, while the olfactory system is diminished, with fewer functional receptor genes than in strepsirrhine primates.[65] [66] This shift correlates with increased reliance on visual cues for foraging and social interactions.[67]Distinctions from Monkeys and Other Primates

Apes differ from monkeys in lacking an external tail, a feature present in most monkey species that aids in balance during quadrupedal locomotion.[68] This absence in apes facilitates greater flexibility in suspensory behaviors, such as brachiation, where the tail would otherwise hinder arm swing.[69] Prosimians, like lemurs and lorises, retain tails but exhibit more primitive grasping adaptations suited to vertical clinging and leaping rather than the sustained suspension seen in apes.[70] In terms of locomotor anatomy, apes possess highly mobile shoulder joints with a broad, cranially oriented scapula that enables extensive rotation and overhead arm positioning, contrasting with the narrower, more laterally positioned scapulae of monkeys adapted for pronograde quadrupedalism.[71] This scapular configuration in apes supports weight suspension from above, reducing reliance on hindlimb propulsion during arboreal travel, whereas monkeys' shoulder morphology prioritizes stable, ground-oriented gait.[72] Prosimians display even less shoulder mobility, with scapulae geared toward leaping rather than prolonged hanging.[73] Apes exhibit larger brain-to-body size ratios compared to monkeys, with relative encephalization quotients higher in hominoids, reflecting adaptations for complex spatial problem-solving in varied arboreal niches.[74] Monkeys, occupying more cursorial and folivorous roles, maintain smaller relative brain sizes suited to predictable foraging patterns.[75] Prosimians have the lowest ratios among primates, correlating with simpler sensory-motor demands in nocturnal, insectivorous lifestyles.[70] Dentally, apes feature Y-5 molar patterns with five cusps arranged in a Y-shape, optimized for shearing fibrous fruits and leaves in canopy environments, distinct from the bilophodont molars of Old World monkeys that form transverse ridges for grinding tougher vegetation.[3] New World monkeys vary but lack this precise configuration, while prosimians retain more primitive, multi-cusped molars without the derived Y-5 shearing efficiency.[76] Ecologically, apes lack specialized features like cheek pouches for food storage, common in some Old World monkeys for opportunistic caching during terrestrial foraging, and ischial callosities for prolonged ground sitting, which monkeys use in savanna habitats.[77] Instead, apes' niches emphasize suspensory access to high-canopy resources, differing from monkeys' versatile quadrupedalism across arboreal and terrestrial zones, and prosimians' niche in understory insectivory with wet noses for scent detection.[78]Behavior and Ecology

Social Structures and Group Dynamics

Gibbons, the lesser apes, typically live in small, stable family units composed of a monogamous breeding pair and their immature offspring, ranging from 2 to 6 individuals. These units maintain exclusive territories defended through coordinated duet singing, primarily by adults, which serves to advertise pair bonds and deter intruders. Among the great apes, social structures diverge significantly by species. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) form large communities of 20 to 150 individuals exhibiting fission-fusion dynamics, where the group splits into temporary parties of 3 to 10 members for foraging and reconvenes at night. Male chimpanzees remain in their natal community, forming linear dominance hierarchies enforced through aggressive displays, coalitions, and occasional lethal violence, while females typically disperse at adolescence to avoid inbreeding.[79][80][81] Bonobos (Pan paniscus) also organize in multi-male, multi-female communities with fission-fusion patterns, but feature stronger female bonds and matrifocal structures where coalitions of related females hold higher status than males. Group sizes vary similarly to chimpanzees, with interactions emphasizing affiliation over aggression, though males form kin-based alliances for status. Females disperse from natal groups, promoting genetic diversity.[82][83] Gorillas (Gorilla spp.) reside in cohesive, harem-like troops averaging 5 to 30 members, led by a dominant silverback male who mates with multiple females (typically 3 to 6) and their offspring. The silverback maintains cohesion through displays and protects against predators and rivals; females often transfer between groups, while young males may leave to form bachelor groups or challenge for leadership. Infanticide occurs when a new silverback assumes control, killing unrelated infants to eliminate future competitors and resume female reproduction sooner.[84][85][86] Orangutans (Pongo spp.) exhibit semi-solitary organization, with flanged adult males ranging independently over large territories and unflanged males or females associating transiently, mainly mothers with dependent young for 6 to 8 years. Social interactions are infrequent and opportunistic, lacking stable groups, though males may consort with estrous females briefly.[87][88] Dominance in ape groups is generally established via physical displays, vocalizations, and aggression rather than constant conflict, with coalitions enhancing status in chimpanzees and bonobos. Infanticide by unrelated males is documented in chimpanzees and gorillas, accelerating interbirth intervals by ending lactation amenorrhea, though rarer in bonobos and absent in orangutans. Allomothering, where non-mothers assist in infant care, occurs in gorillas and chimpanzees, fostering group cohesion, while cooperation manifests in collective defense against predators or rivals, particularly in chimpanzees. Sex-biased dispersal predominates, with female transfer common across species to mitigate inbreeding, except in gibbons where both sexes may disperse.[89][86][90]Diet, Foraging, and Habitat Adaptation

Apes exhibit primarily plant-based diets dominated by frugivory, with fruit comprising 50-80% of intake in many species, supplemented by foliage, pith, bark, insects, and occasionally other animal matter.[91] [92] This composition reflects adaptations to tropical forest habitats where ripe fruit patches provide high-energy resources, though dietary flexibility allows shifts to lower-quality fallback foods like mature leaves and herbs during seasonal scarcity to maintain energy balance.[93] Such strategies prioritize nutrient-dense patches, minimizing travel costs while exploiting spatiotemporal fruit availability, as evidenced by selective foraging in high-quality arboreal sources.[94] Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) display the most opportunistic diets among great apes, with fruit at 50-75% but including significant animal protein from insects (up to 10%) and hunted vertebrates like colobus monkeys, alongside leaves and pith.[91] Foraging involves tool-assisted extraction, such as modifying sticks for termite fishing from epigeal mounds, where probes are inserted to withdraw adherent termites, enhancing caloric intake during lean periods.[95] In African rainforests, this enables exploitation of understory insects inaccessible without tools, linking habitat structure—dense undergrowth and termite nests—to specialized behaviors.[96] Gorillas (Gorilla spp.) are folivore-frugivores, with western lowland populations consuming up to 230 plant items but favoring herbaceous vegetation (40-60%) over fruit (15-25%), contrasting mountain gorillas' lower frugivory (<5% fruit).[97] [98] They process fibrous foods via hindgut fermentation, adapting to central African rainforests rich in herbs and shoots as fallback staples when fruit phenology declines, thus buffering against seasonal gaps in preferred ripe fruits.[92] Foraging emphasizes ground-level browsing in clearings, with selective intake of protein-rich stems and avoidance of tannins, optimizing digestion in habitats with variable fruit productivity.[99] Orangutans (Pongo spp.), particularly Bornean populations, rely heavily on fruit (60-80%) in peat swamp forests, where low soil nutrients yield unpredictable mast fruiting events, prompting fallback to bark, leaves, and insects during inter-mast periods.[100] These habitats, with acidic peat and sparse canopies, necessitate arboreal travel adjustments—shorter strides and branch compliance—to access dispersed resources, sustaining energy via prolonged suspension feeding.[101] [102] Gibbons (Hylobatidae), as lesser apes, maintain frugivorous diets with fruits at ~55%, leaves ~25%, and flowers/seeds supplementing in Southeast Asian dipterocarp forests. Foraging centers on terminal branch feeding for pulpy fruits, with daily patterns prioritizing fruit-rich breakfast trees to plan brachiation routes, adapting to canopy gaps by favoring energy-maximizing patches over uniform depletion.[103] Seasonal fallback to leaves sustains intake amid fruit shortages, aligning with habitats of emergent trees and lianas that support suspensory locomotion for efficient harvest.[104]Locomotion and Daily Activities

Gibbons, as lesser apes, exhibit highly specialized arboreal locomotion dominated by brachiation, a form of arm-swinging suspensory movement that constitutes more than 50% of their active time, enabling efficient travel through the forest canopy. [105] This mode relies on elongated forelimbs and flexible shoulder joints adapted for continuous swinging between branches, with gibbons spending the vast majority of their time in trees. [106] In contrast, great apes employ knuckle-walking for terrestrial quadrupedal progression, supporting body weight on the dorsal surfaces of flexed fingers, a trait prominent in African species like chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas. [107] Arboreally, great apes engage in clambering and climbing, utilizing powerful upper body strength to navigate larger supports and vertical trunks, though less suspensory than gibbons. [108] Apes are predominantly diurnal, with activity patterns structured around morning travel and foraging followed by midday resting to conserve energy in tropical environments, allocating roughly 30-50% of daylight hours to rest depending on species and resource availability. [109] Daily travel distances vary by habitat and diet but typically range from 3-5 km for most great apes, with chimpanzees occasionally covering up to 10 km in fruit-scarce periods to track dispersed resources. [109] Nocturnal activity is rare among apes, though some crepuscular behaviors occur at dawn or dusk for group movement or predator avoidance in species like orangutans. [110] Great apes routinely construct new nests each evening from branches and leaves for overnight sleeping, a behavior that enhances hygiene by abandoning old sites and provides elevated protection from ground predators. [111] This nightly rebuilding, observed across chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, consumes 1-2 hours of late-afternoon activity and reflects adaptations for arboreal safety without permanent shelters. [112] Low-activity periods, often midday siestas in shade, minimize metabolic costs in high-humidity forests where thermoregulation demands energy efficiency. [113]Cognition and Intelligence

Tool Use and Problem-Solving

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) exhibit the most extensive and varied tool use among apes in the wild, including probe tools modified from twigs or sticks for extracting termites from mounds, a behavior first documented in 1960 at Gombe Stream National Park by Jane Goodall.[114] These tools often involve sequential use of a perforating stick followed by a fishing probe, with individuals selecting and modifying stems based on length, flexibility, and frayed tips for optimal efficacy, as observed in the Ndoki Forest.[115] Nut-cracking with stone hammers and anvils is prevalent in West African populations, such as at Taï National Park, where chimpanzees select heavy stones (averaging 2-7 kg) suited to nut hardness and reuse sites over years, leaving archaeological traces of durable tools and fragments.[116][117] Tool repertoires vary culturally across communities, with over 30 distinct behaviors transmitted socially rather than genetically, as evidenced by absence in some groups despite similar habitats.[118] Orangutans (Pongo spp.) demonstrate tool use primarily in Sumatran populations at sites like Suaq Balimbing, where they fashion sticks to extract insects from tree holes or use leaves as gloves to handle irritant fruits and as impromptu umbrellas during rain.[119][120] Wild individuals have been observed improvising shelters by weaving branches or using tools for seed extraction, with innovations like hanging tools for future reuse documented in 2018.[121] These behaviors occur at higher frequencies in resource-rich swamp forests but are less common in Bornean orangutans, reflecting ecological opportunities rather than cognitive deficits.[122] Tool use in gorillas (Gorilla spp.) is rarer in the wild, with the first verified instance in 2005 involving a western lowland female using a branch as a probe to gauge swamp water depth before crossing, followed by occasional ant-fishing or stick-testing in mountain gorillas.[123] Gibbons (family Hylobatidae), being strictly arboreal and adapted to fruit-abundant forests, show minimal tool use, limited to rare captive observations of branch manipulation for food extraction, attributable to reduced selective pressure in their habitat where manual dexterity suffices.[124][125] In captive settings, apes like chimpanzees innovate tool solutions to novel puzzles, such as modifying objects into metatools or overcoming traps, with early proficiency in simple manipulations but challenges in complex sequences mirroring wild constraints on elaboration.[126][127] Wild tool complexity remains bounded by immediate ecological demands, with no sustained material culture accumulation observed.[128]Learning, Memory, and Communication

Chimpanzees demonstrate superior working memory for numerical sequences compared to adult humans in tasks requiring rapid recall of briefly presented digits. In experiments conducted by Tetsuro Matsuzawa at Kyoto University's Primate Research Institute, young chimpanzees such as Ayumu remembered the positions and order of nine numerals flashed for 200 milliseconds, outperforming human participants who required longer exposure times.[129] This capability persists in trained individuals like Ai, the first chimpanzee to use Arabic numerals symbolically, achieving errorless performance in sequencing up to nine items after extensive training starting in 1979.[130] Spatial memory in chimpanzees also excels, with individuals forming long-term recollections of food cache locations after minimal exposure, as evidenced by field studies in Uganda's Budongo Forest where subjects relocated hidden rewards with high accuracy after delays of up to nine days.[131] Social learning in apes relies heavily on imitation rather than individual trial-and-error, particularly in great apes raised in human-like environments. Enculturated chimpanzees and orangutans exhibit deferred imitation, reproducing observed actions after delays of up to 24 hours, a process distinct from asocial learning as it involves selective copying of demonstrator behaviors.[132] Mirror self-recognition, a marker of self-awareness tested via the mark procedure, occurs reliably in great apes including chimpanzees, orangutans, and some gorillas, who touch marked body parts visible only in reflection, but fails in lesser apes like gibbons, indicating a cognitive threshold tied to encephalization rather than phylogenetic proximity to humans.[133] Ape communication features intentional gestures and vocalizations that convey context-specific meanings without syntactic structure. Great ape gestures, such as arm extensions for play invitations or ground slaps for copulation requests, exhibit first-order intentionality: producers adjust signals based on recipient attention and response, persisting or desisting accordingly across species like chimpanzees and bonobos.[134] Vocal signals, including chimpanzee pant-hoots for group coordination or alarm calls differentiated by predator type, function referentially but lack recursive syntax or combinatorial rules observed in human language, relying instead on innate or learned repertoires limited to about 30-60 gesture types per individual.[135] These systems prioritize immediate social goals over propositional content, with empirical playback studies confirming recipients respond appropriately to gesture intent without evidence of displaced reference.[136]Comparative Assessments with Humans

Apes demonstrate episodic-like memory, as evidenced by chimpanzees recalling the location, content, and timing of past events, such as distinguishing food caches hidden at different intervals and revisiting them accordingly over periods exceeding a year.[137][138] This capacity integrates "what," "where," and "when" elements, mirroring aspects of human episodic memory but lacking the autonoetic awareness of re-experiencing subjective past states.[139] Proxies for theory of mind appear in apes through behaviors like gaze-following and tactical deception, where chimpanzees infer others' attentional states to hide resources or compete effectively.[140] However, empirical tests reveal limitations; apes rarely pass stringent false-belief tasks requiring attribution of unobservable mental states, succeeding primarily on observable cues rather than full representational understanding, unlike consistent human performance from age four.[141][142] Apes exhibit cultural transmission of behaviors, such as nut-cracking techniques in chimpanzees, yet lack cumulative culture, where innovations ratchet into increasingly complex forms across generations; experimental assessments show no progressive efficiency gains in tool use, with successes attributable to individual invention or simple imitation rather than modification of prior techniques.[143][144] Abstract reasoning remains constrained, with no evidence of symbolic manipulation or hypothetical scenario planning beyond immediate contexts. Genetic differences underpin vocalization gaps; the FOXP2 gene in humans features two amino acid substitutions absent in chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas, correlating with enhanced fine motor control for articulate speech and vocal learning, which apes do not exhibit despite shared core sequence conservation.[145][146] Human prefrontal cortex shows disproportionate expansion relative to body size compared to apes, particularly in frontopolar regions supporting executive functions like planning and integration of abstract information, enabling capabilities beyond ape domain-specific adaptations.[147][148] Ape prosocial behaviors, often labeled as empathy, align with kin selection and reciprocal altruism mechanisms, prioritizing genetic relatives or exchange partners without evidence of impartial moral judgment or rule-based ethics independent of immediate fitness benefits.[149] Intelligence in apes is modular, excelling in spatial navigation or tool manipulation tasks but failing generalization across unrelated domains, contrasting human fluid intelligence that transfers principles broadly.[150][151]Reproduction and Life History

Mating Systems and Parental Care