Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Multistable perception

View on Wikipedia

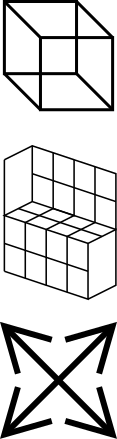

Multistable perception (or bistable perception) is a perceptual phenomenon in which an observer experiences an unpredictable sequence of spontaneous subjective changes. While usually associated with visual perception (a form of optical illusion), multistable perception can also be experienced with auditory and olfactory percepts.

Classification

[edit]Perceptual multistability can be evoked by visual patterns that are too ambiguous for the human visual system to definitively and uniquely interpret. Familiar examples include the Necker cube, Schroeder staircase, structure from motion, monocular rivalry, and binocular rivalry, but many more visually ambiguous patterns are known. Because most of these images lead to an alternation between two mutually exclusive perceptual states, they are sometimes also referred to as bistable perception.[1]

Auditory and olfactory examples can occur when there are conflicting, and so rival, inputs into the two ears[2] or two nostrils.[3]

Characterization

[edit]The transition from one precept (an undefined term) to its alternative (the defined term) is called a perceptual reversal (Paradigm shift). They are spontaneous and stochastic events that cannot be eliminated by intentional efforts, although some control over the alternation process is learnable. Reversal rates vary drastically between stimuli and observers. They are slower for people with bipolar disorder.[4][5]

Cultural history

[edit]Human interest in these phenomena can be traced back to antiquity.[citation needed] The fascination with multistable perception probably comes from the active nature of endogenous perceptual changes or from the dissociation of dynamic perception from constant sensory stimulation.

Multistable perception was a common feature in the artwork of the Dutch lithographer M. C. Escher, who was strongly influenced by mathematical physicists such as Roger Penrose.[citation needed]

Examples

[edit]Real-world phenomena

[edit]Photographs of craters, from either the moon or other planets including our own, can exhibit this phenomenon. Craters in stereo vision, such as our eyes, normally appear concave. However, in monocular presentations, such as photographs, the elimination of our depth perception causes multistable perception, which can cause the craters to look like plateaus rather than pits. For humans, the "default" interpretation comes from an assumption of top-left lighting, so that rotating the image by 180 degrees can cause the perception to suddenly switch.[6][7] This phenomenon is called the concave/convex, or simply up/down, ambiguity, and it confuses computer vision as well.[8]

In popular culture

[edit]In literature, the science fiction novel Dhalgren by Samuel R. Delany, contains circular text, multistable perception, and multiple entry points.[citation needed]

Multistable perception arises with the theater segments of Mystery Science Theater 3000, as due to the construction of the Crow T. Robot puppet, its head can appear to be facing towards the camera rather than towards the film being shown. This was addressed by the creators of the series, even likening Crow to a Necker cube[9] or The Spinning Dancer.[when?]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Alais, D; Blake, R., eds. (2005). Binocular Rivalry. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01212-6.

- Kruse, P.; Stadler, M. (1995). Multistable Cognitive Phenomena. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-57082-2.

Sources

[edit]- ^ Eagleman, D. (2001). "Visual Illusions and Neurobiology" (PDF). Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2 (12): 920–926. doi:10.1038/35104092. PMID 11733799. S2CID 205023280. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- ^ Deutsch, D. (1974). "An Auditory Illusion". Nature. 251 (5473): 307–309. doi:10.1038/251307a0. PMID 4427654. S2CID 4273134.

- ^ Zhou, W.; Chen, D. (2009). "Binaral Rivalry Between the Nostrils and in the Cortex". Current Biology. 19 (18): 1561–1565. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.052. PMC 2901510. PMID 19699095.

- ^ Pettigrew, J. D.; Miller, S. M. (1998). "A 'sticky' interhemispheric switch in bipolar disorder?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1411): 2141–2148. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0551. PMC 1689515. PMID 9872002.

- ^ Miller, S. M.; Gynther, B. D.; Heslop, K. R.; Liu G. B.; Mitchell, P. B.; Ngo, T. T.; Pettigrew, J. D.; Geffen, L. B. (2003). "Slow Binocular Rivalry in Bipolar Disorder" (PDF). Psychological Medicine. 33 (4): 683–692. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.9166. doi:10.1017/S0033291703007475. PMID 12785470. S2CID 30727987. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2006-09-24.

- ^ "A lunar illusion you'll flip over". Discover Magazine.

- ^ Minutephysics (29 June 2017). "The "Mountain Or Valley?" Illusion". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12.

- ^ Breuß, Michael; Mansouri, Ashkan; Cunningham, Douglas (2018). "The Convex-Concave Ambiguity in Perspective Shape from Shading". Proceedings of the OAGM Workshop 2018. doi:10.3217/978-3-85125-603-1-13. ISBN 978-3-85125-603-1.

- ^ Trace Beaulieu ... (1996). The Mystery Science Theater 3000 Amazing Colossal Episode Guide. Bantam. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-553-37783-5.

External links

[edit]- VisualFunHouse Optical Illusions Multistable perception Optical Illusions

- A collection of visually ambiguous patterns

- Miller, S. M.; Liu, G. B.; Ngo, T. T.; Hooper, G.; Riek, S.; Carson, R. G.; Pettigrew, J. D. (2000). "Interhemispheric Switching Mediates Perceptual Rivalry". Current Biology. 10 (7): 383–392. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00416-4. PMID 10753744. S2CID 51808719. Archived from the original on 2021-02-11. Retrieved 2006-01-21.

- Ambiguous figures Ambiguity of spatial perception (fr)