Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

American School (economics)

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

Major types

|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

The American School, also known as the National System, represents three different yet related constructs in politics, policy and philosophy. The policy existed from the 1790s to the 1970s, waxing and waning in actual degrees and details of implementation. Historian Michael Lind describes it as a coherent applied economic philosophy with logical and conceptual relationships with other economic ideas.[1]

It is the macroeconomic philosophy that dominated United States national policies from the time of the American Civil War until the mid-20th century.[2][3][4][5][6][7] Closely related to mercantilism, it can be seen as contrary to classical economics. It consisted of these three core policies:

- Protecting industry through selective high tariffs (especially 1861–1932).

- Government investments in infrastructure creating targeted internal improvements (especially in transportation).

- A national bank with policies that promote the growth of productive enterprises rather than speculation.[8][9][10][11]

The American School's key elements were promoted by John Quincy Adams and his National Republican Party, Henry Clay and the Whig Party and Abraham Lincoln through the early Republican Party which embraced, implemented and maintained this economic system.[12]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

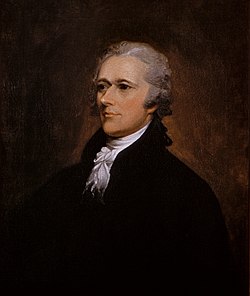

The American School of economics represented the legacy of Alexander Hamilton, who in his Report on Manufactures, argued that the U.S. could not become fully independent until it was self-sufficient in all necessary economic products. Hamilton rooted this economic system, in part, in the successive regimes of Colbert's France and Elizabeth I's England, while rejecting the harsher aspects of mercantilism, such as seeking colonies for markets. As later defined by Senator Henry Clay who became known as the Father of the American System because of his impassioned support thereof, the American System was to unify the nation north to south, east to west, and city to farmer.[13]

Frank Bourgin's 1989 study of the Constitutional Convention shows that direct government involvement in the economy was intended by the Founders.[14] The goal, most forcefully articulated by Hamilton, was to ensure that dearly won political independence was not lost by being economically and financially dependent on the powers and princes of Europe. The creation of a strong central government able to promote science, invention, industry and commerce, was seen as an essential means of promoting the general welfare and making the economy of the United States strong enough for them to determine their own destiny.

Jefferson and Madison strongly opposed Hamilton's program, but were forced to implement it by the exigencies of the embargo, begun in December 1807 under the Non-Intercourse Act, and the War of 1812 against Britain.[15]

A number of programs by the federal government undertaken in the period prior to the Civil War gave shape and substance to the American School. These programs included the establishment of the Patent Office in 1802, the creation of the Survey of the Coast (later renamed the United States Coast Survey and then the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey) in 1807 and other measures to improve river and harbor navigation created by the 1824 Rivers and Harbors Act.

Other developments included the various Army expeditions to the west, beginning with Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery in 1804 and continuing into the 1870s (see for example, the careers of Major Stephen Harriman Long and Major General John C. Frémont), almost always under the direction of an officer from the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, and which provided crucial information for the overland pioneers that followed (see, for example, the career of Brigadier General Randolph B. Marcy), the assignment of Army Engineer officers to assist or direct the surveying and construction of the early railroads and canals, and the establishment of the First Bank of the United States and Second Bank of the United States as well as various protectionist measures such as the Tariff of 1828.

Leading proponents were economists Friedrich List (1789–1846) and Henry Carey (1793–1879). List was a leading 19th Century German and American economist who called it the "National System" and developed it further in his book The National System of Political Economy Carey called this a Harmony of Interests[16] in his book by the same name, a harmony between labor and management, and as well a harmony between agriculture, manufacturing, and merchants.

The name "American System" was coined by Clay to distinguish it, as a school of thought, from the competing theory of economics at the time, the "British System" represented by Adam Smith in his work Wealth of Nations.[17]

Central policies

[edit]The American School included three cardinal policy points:

- Support industry: the advocacy of protectionism, and opposition to free trade – particularly for the protection of "infant industries" and those facing import competition from abroad. Examples: Tariff Act of 1789, Tariff Act of 1816 and Morrill Tariff.

- Create physical infrastructure: government finance of internal improvements to speed commerce and develop industry. This involved the regulation of privately held infrastructure, to ensure that it meets the nation's needs. Examples: Cumberland Road and Union Pacific Railroad.

- Create financial infrastructure: a government sponsored National Bank to issue currency and encourage commerce. This involved the use of sovereign powers for the regulation of credit to encourage the development of the economy, and to deter speculation. Examples: First Bank of the United States, Second Bank of the United States, and National Banking Act.[18]

Henry C. Carey, a leading American economist and adviser to Abraham Lincoln, in his book Harmony of Interests, displays two additional points of this American School economic philosophy that distinguishes it from the systems of Adam Smith or Karl Marx:

- Government support for the development of science and public education through a public 'common' school system and investments in creative research through grants and subsidies.

- Rejection of class struggle, in favor of the "Harmony of Interests" between: owners and workers, farmers and manufacturers, the wealthy class and the working class.[19]

In a passage from his book, The Harmony of Interests, Carey wrote concerning the difference between the American System and British System of economics:

Two systems are before the world; ... One looks to increasing the necessity for commerce; the other to increasing the power to maintain it. One looks to underworking the Hindoo [sic], and sinking the rest of the world to his level; the other to raising the standard of man throughout the world to our level. One looks to pauperism, ignorance, depopulation, and barbarism; the other to increasing wealth, comfort, intelligence, combination of action, and civilization. One looks towards universal war; the other towards universal peace. One is the English system; the other we may be proud to call the American system, for it is the only one ever devised the tendency of which was that of elevating while equalizing the condition of man throughout the world.[19]

In the Civil War, a shortage of specie led to the issue of such a fiat currency, called United States Notes, or "greenbacks". Towards the end of the Civil War in March 1865, Henry C. Carey, Lincoln's economic advisor, published a series of letters to the Speaker of the House entitled "The Way to Outdo England Without Fighting Her." Carey called for the continuance of the greenback policy even after the War, while also raising the reserve requirements of the banks to 50%.[20] This would have allowed the US to develop its economy independent of foreign capital (primarily British gold). Carey wrote:

The most serious move in the retrograde direction is that one we find in the determination to prohibit the further issue of [United States Notes] ... To what have we been indebted for [the increased economic activity]? To protection and the " greenbacks"! What is it that we are now laboring to destroy? Protection and the Greenback! Let us continue on in the direction in which we now are moving, and we shall see ... not a re-establishment of the Union, but a complete and final disruption of it.

Carey's plans did not come to fruition as Lincoln was assassinated the next month and new President Andrew Johnson supported the gold standard, and by 1879 the U.S. was fully back on the gold standard.

Advocacy

[edit]

The "American System" was the name given by Henry Clay in a speech before Congress advocating an economic program[21] based on the economic philosophy derived from Alexander Hamilton's economic theories. Clay's policies called for a high tariff to support internal improvements such as road-building, and a national bank to encourage productive enterprise and to form a national currency as Hamilton had advocated as Secretary of the Treasury.

Clay first used the term "American System" in 1824, although he had been working for its specifics for many years previously. Portions of the American System were enacted by Congress. The Second Bank of the United States was rechartered in 1816 for 20 years. High tariffs were maintained from the days of Hamilton until 1832. However, the national system of internal improvements was never adequately funded; the failure to do so was due in part to sectional jealousies and constitutional scruples about such expenditures.[22]

Clay's plan became the leading tenet of the National Republican Party of John Quincy Adams and the Whig Party of himself and Daniel Webster.

The "American System" was supported by New England and the Mid-Atlantic, which had a large manufacturing base. It protected their new factories from foreign competition.

The South opposed the "American System" because its plantation owners were heavily reliant on production of cotton for export, and the American System produced lower demand for their cotton and created higher costs for manufactured goods. After 1828 the United States kept tariffs low until the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1861.

Executive opposition to the American System by the Jacksonians

[edit]Opposition to the economic nationalism embodied by Henry Clay's American System came primarily from the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson, Martin van Buren, and James K. Polk. These three presidents styled themselves as the peoples' politicians, seeking to protect both the agrarian frontier culture and the strength of the Union. Jackson in particular, the founder of the movement, held an unflinching commitment to what he viewed as the sanctity of the majority opinion. In his first annual message to Congress, Jackson proclaimed that "the first principle of our system [is] that the majority govern".[23] This ideology governed Jackson's actions throughout his presidency, and heavily influenced his protégé Martin van Buren as well as the final Jacksonian president, James K. Polk.

This commitment to the majority and to the voiceless came in direct conflict with many elements of the American System. The Jacksonian presidents saw key tenets of the American System, including the support for the Second Bank of the United States and advocacy of protectionist tariffs, as serving moneyed or special interests rather than the majority of Americans. The Jacksonians opposed other elements of Clay's ideology, including support for internal infrastructural improvements, on the grounds that they represented governmental overstretch as well. Several key events, legislative conflicts, and presidential vetoes shaped the substantive opposition to the American System.

Second Bank of the United States and the Bank War

[edit]The first and most well-known battle between Jacksonians and Clay focused on the struggle over renewing the charter of the Second Bank of the United States. In Andrew Jackson's first annual message to Congress in 1829, he declared that "[b]oth the constitutionality and the expediency of the law creating this bank are well questioned by a large portion of our fellow-citizens, and it must be admitted by all that it has failed in the great end of establishing a uniform and sound currency".[24] He further attacked the proponents of renewing the bank's charter, scathingly referring to the "stockholders" seeking a renewal of their "privileges".[24]

This rhetoric, portraying the supporters of the bank as privileged individuals, and claiming the opposition of "a large portion of our fellow-citizens" crystallizes Jackson's majoritarian distaste for the special interest serving economic nationalism embodied in the American System. Jackson's Secretary of the Treasury Roger B. Taney effectively summed up Jackson's opposition to the Second Bank of the United States: ""It is a fixed principle of our political institutions to guard against the unnecessary accumulation of power over persons and property in any hands. And no hands are less worthy to be trusted with it than those of a moneyed corporation".[25]

The two sides of the debate became even more starkly defined as a result of the actions of Second Bank President Nicholas Biddle and Henry Clay himself. Upon hearing of Jackson's distaste for his bank, Biddle immediately set about opening new branches of the bank in key political districts in hopes of manipulating Congressional opinion.[26] Although this action indeed helped acquire the votes necessary to pass the bill in Congress, it enraged Jackson. Jackson saw this manipulation as clear evidence of the penchant of a national bank to serve private, non-majoritarian interests.[26]

Henry Clay's American System supported the necessity for central institutions to "take an activist role in shaping and advancing the nation's economic development".[26] The bank thus fit well into Clay's worldview, and he took advantage of Biddle's manipulation in order to pass the renewal bill through Congress, despite expecting Jackson's inevitable veto. Clay hoped that when Jackson vetoed the bill, it would more clearly differentiate the two sides of the debate which Clay then sought to use to his advantage in running for president.[26] With battle lines set, Jackson's majoritarian opposition to the Second Bank of the United States helped him be elected to a second term.

Tariff question

[edit]The question of protective tariffs championed by the American System proved one of the trickiest for Jacksonian presidents. Tariffs disproportionately benefited the industrial interests of the North while causing injury to the import-dependent agrarian South and West. As a result, the issue proved extremely divisive to the nation's unity, something Jacksonian presidents sought to protect at all costs. The Jacksonian presidents, particularly the southern-born Jackson, had to be extremely cautious when lowering tariffs in order to maintain their support in the North.[27]

However, the tariffs indeed represented an economic nationalism that primarily benefited the Northern States, while increasing the cost of European imports in the South. This ran strongly contrary to Jacksonian ideals. In the end, despite Northern objections, both President Jackson and President Polk lowered tariffs. Jackson reformed the Tariff of 1828 (also known as the Tariff of Abominations) by radically reducing rates in the Tariff of 1832. This helped stave off the Southern nullification crisis, in which Southern states refused to enact the tariff, and threatened secession if faced with governmental coercion.[27]

The bill that reduced the Tariff of 1828 was co-authored by Henry Clay in a desperate attempt to maintain national unity.[27] Polk, on the other hand, in his characteristically efficient way, managed to push through significant tariff reductions in the first 18 months of his term.[28]

Opposition to government-financed internal improvements

[edit]The final bastion of Jacksonian opposition to Clay's American System existed in relation to the use of government funds to conduct internal improvements. The Jacksonian presidents feared that government funding of such projects as roads and canals exceeded the mandate of the federal government and should not be undertaken.[29] Van Buren believed very strongly that "[t]he central government, unlike the states", had no obligation to provide relief or promote the general welfare.[29]

This stance kept faith with the tenets of Jeffersonian republicanism, notably its agrarianism and strict constructionism, to which van Buren was heir".[29] As heir to the legacy of Van Buren and Jackson, Polk was similarly hostile to internal improvement programs, and used his presidential veto to prevent such projects from reaching fruition.[30]

Implementation

[edit]An extra session of congress was called in the summer of 1841 for a restoration of the American system. When the tariff question came up again in 1842, the compromise of 1833 was overthrown, and the protective system placed in the ascendant.

Due to the dominance of the then Democratic Party of Van Buren, Polk, and Buchanan the American School was not embraced as the economic philosophy of the United States until the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, who, with a series of laws during the American Civil War, was able to fully implement what Hamilton, Clay, List, and Carey theorized, wrote about, and advocated.

As soon as Lincoln took office, the old Whig coalition finally controlled the entire government. It immediately tripled the average tariff, began to subsidize the construction of a transcontinental railroad in California even though a desperate war was being waged, and on February 25, 1862, the Legal Tender Act empowered the secretary of the treasury to issue paper money ('greenbacks') that were not immediately redeemable in gold or silver.[2][10][11]

The United States continued these policies throughout the later half of the 19th century.

President Ulysses S Grant acknowledged the perceived efficacy of tariff protection in reference to Britain's success during the Industrial Revolution, when tariff rates on manufactures peaked at 57%:

For centuries England has relied on protection, has carried it to extremes and has obtained satisfactory results from it. There is no doubt that it is to this system that it owes its present strength.

President William McKinley (1897–1901) stated at the time:

[They say] if you had not had the Protective Tariff things would be a little cheaper. Well, whether a thing is cheap or dear depends upon what we can earn by our daily labor. Free trade cheapens the product by cheapening the producer. Protection cheapens the product by elevating the producer. Under free trade the trader is the master and the producer the slave. Protection is but the law of nature, the law of self-preservation, of self-development, of securing the highest and best destiny of the race of man. [It is said] that protection is immoral ... Why, if protection builds up and elevates 63,000,000 [the U.S. population] of people, the influence of those 63,000,000 of people elevates the rest of the world. We cannot take a step in the pathway of progress without benefitting mankind everywhere. Well, they say, 'Buy where you can buy the cheapest'...Of course, that applies to labor as to everything else. Let me give you a maxim that is a thousand times better than that, and it is the protection maxim: 'Buy where you can pay the easiest.' And that spot of earth is where labor wins its highest rewards.[31]

The American System was important in the election politics for and against Grover Cleveland,[7] the first Democrat elected after the Civil War, who, by reducing tariffs protecting American industries in 1893, began rolling back federal involvement in economic affairs, a process that became dominant by the 1920s and continued until Herbert Hoover's attempts to deal with the worsening Great Depression.

Evolution

[edit]As the United States entered the 20th century, the American School was the policy of the United States under such names as American Policy, economic nationalism, National System,[32] Protective System, Protection Policy,[33] and protectionism, which alludes only to the tariff policy of this system of economics.[34][35][36][13][37]

This continued until 1913 when the administration of Woodrow Wilson initiated his The New Freedom policy that replaced the National Bank System with the Federal Reserve System, and lowered tariffs to revenue-only levels with the Underwood Tariff.

The election of Warren G. Harding and the Republican Party in 1920 represented a partial return to the American School through restoration of high tariffs. A subsequent further return was enacted as President Herbert Hoover responded to the 1929 crash and the subsequent bank failures and unemployment by signing the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which some economists considered to have deepened the Great Depression, while others disagree.[38]

The New Deal continued infrastructure improvements through the numerous public works projects of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) as well as the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA); brought massive reform to the banking system of the Federal Reserve while investing in various ways in industry to stimulate production and control speculation; but abandoned protective tariffs while embracing moderate tariff protection (revenue based 20–30% the normal tariff under this) through reciprocity, choosing to subsidize industry as a replacement. At the close of World War II, the United States now dominant in manufacturing with little competition, the era of free trade had begun.[39]

In 1973, when the "Kennedy" Round concluded under President Richard Nixon, who cut U.S. tariffs to all time lows, the New Deal orientation towards reciprocity and subsidy ended, which moved the United States further in the free market direction, and away from its American School economic system.[40][41]

Other nations

[edit]Friedrich List's influence among developing nations has been considerable. Japan has followed his model.[42] It has also been argued that Deng Xiaoping's post-Mao policies were inspired by List[43] as well as recent policies in India.[44][45]

See also

[edit]- American System (economic plan)

- Protectionism in the United States

- Henry Charles Carey

- Anders Chydenius

- Daniel Raymond

- Friedrich List

- Economic history of the United States

- Import substitution industrialization, a key feature of the American System adopted in much of the Third World during the 20th century

- Johann Heinrich von Thünen

- Lincoln's expansion of the federal government's economic role

- National Policy, a similar economic plan used by Canada circa 1867–1920s

- William Petty

- Report on Manufactures

- First Report on the Public Credit

- Second Report on Public Credit

- Report on a Plan for the Further Support of Public Credit

General:

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Free Trade Fallacy" New America.

- ^ a b "Second Bank of the United States" U-S-History.com.

- ^ "Republican Party Platform of 1860" presidency.ucsb.edu

- ^ "Republican Party Platform of 1856" presidency.ucsb.edu.

- ^ Pacific Railway Act (1862) ourdocuments.gov.

- ^ "History of U.S. Banking" SCU.edu Archived 2007-12-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b ANDREWS, E. Benjamin, p. 180 of Scribner's Magazine Volume 18 #1 (January–June 1896); "A History of the Last Quarter-Century".

- ^ Lind, Michael: "Lincoln and his successors in the Republican party of 1865–1932, by presiding over the industrialization of the United States, foreclosed the option that the United States would remain a rural society with an agrarian economy, as so many Jeffersonians had hoped." and "... Hamiltonian side ... the Federalists; the National Republicans; the Whigs, the Republicans; the Progressives." — "Hamilton's Republic" Introduction pp. xiv–xv. Free Press, Simon & Schuster: 1997. ISBN 0-684-83160-0.

- ^ Lind, Michael: "During the nineteenth century the dominant school of American political economy was the "American School" of developmental economic nationalism ... The patron saint of the American School was Alexander Hamilton, whose Report on Manufactures (1791) had called for federal government activism in sponsoring infrastructure development and industrialization behind tariff walls that would keep out British manufactured goods ... The American School, elaborated in the nineteenth century by economists like Henry Carey (who advised President Lincoln), inspired the "American System" of Henry Clay and the protectionist import-substitution policies of Lincoln and his successors in the Republican party well into the twentieth century." — "Hamilton's Republic" Part III "The American School of National Economy" pp. 229–30. Free Press, Simon & Schuster: 1997. ISBN 0-684-83160-0.

- ^ a b Richardson, Heather Cox: "By 1865, the Republicans had developed a series of high tariffs and taxes that reflected the economic theories of Carey and Wayland and were designed to strengthen and benefit all parts of the American economy, raising the standard of living for everyone. As a Republican concluded ... "Congress must shape its legislation as to incidentally aid all branches of industry, render the people prosperous, and enable them to pay taxes ... for ordinary expenses of Government." — "The Greatest Nation of the Earth" Chapter 4, "Directing the Legislation of the Country to the Improvement of the Country: Tariff and Tax Legislation" pp. 136–37. President and Fellows of Harvard College: 1997. ISBN 0-674-36213-6.

- ^ a b Boritt, Gabor S: "Lincoln thus had the pleasure of signing into law much of the program he had worked for through the better part of his political life. And this, as Leonard P. Curry, the historian of the legislation has aptly written, amounted to a "blueprint for modern America." and "The man Lincoln selected for the sensitive position of Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase, was an ex-Democrat, but of the moderate variety on economics, one whom Joseph Dorfman could even describe as 'a good Hamiltonian, and a western progressive of the Lincoln stamp in everything from a tariff to a national bank.'" — "Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream" Chapter 14, "The Whig in the White House" pp. 196–97. Memphis State University Press: 1994. ISBN 0-87870-043-9.

- ^ Howe, Daniel Walker "The policies of tariff protection, federally sponsored internal improvements, and national banking that were later to be known as the “American System” took coherent shape in the years between 1816 and 1828 and were coherent with the “national” wing of the Republican party." - "The Political Culture of the American Whigs, pp. 48-49. University of Chicago Press, 1979. "J.L.M. Curry, "Confederate States and Their Constitution", The Galaxy, New York, 1874 cornell.edu".

- ^ a b "George D. Prentice, "Life of Henry Clay", The North American Review, Boston Massachusetts, 1831".

- ^ Bourgin, Frank (1989). The Great Challenge: The Myth of Laissez-Faire in the Early Republic. New York, NY: George Braziller Inc. ISBN 0-06-097296-3.

- ^ Earle, Edward Mead: "It is one of the ironies of history that Hamilton's political opponents Jefferson and Madison did more than Hamilton himself to give effect to his protectionist and nationalist views of economic policy. The Embargo, which Jefferson initiated in December 1807, the Non-Intercourse Act, and the succeeding war with Great Britain, upon which Madison reluctantly embarked, had the practical result of closing virtually all avenues of foreign trade and making the United States dependent upon its own resources for manufactures and munitions of war. The industries which were born under the stress and necessity of the years 1808 to 1815 were the infants to which the nation gave protection in 1816 and in a succession of tariff acts thereafter.... Jefferson in January 1816 wrote an exceedingly bitter denunciation of those who cited his former free trade views as 'a stalking horse, to cover their disloyal propensities to keep us in eternal vassalage to a foreign and unfriendly people [the British].'" — Makers of Modern Strategy: Military Thought from Machiavelli to Hitler, Chapter 6, "Adam Smith, Alexander Hamilton, Friedrich List: The Economic Foundations of Military Power", pp. 138–139. Princeton University Press: 1943, 1971. ISBN 0-691-01853-7.

- ^ Carey, Henry Charles (c. 1872). Miscellaneous works of Henry C. Carey ...

- ^ "cornell.edu".[full citation needed]

- ^ "American System". The Reader's Companion to American History. hmco.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2004. Retrieved 14 February 2006.

- ^ a b Henry C. Carey, Harmony of Interests

- ^ Carey, Henry Charles (1865). The way to outdo England without fighting her. Making of America.

- ^ The Senate 1789–1989 Classic Speeches 1830–1993 Volume three, Bicentennial edition, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington

- ^ "Ideas and Movements: American System" U-S-History.com".

- ^ Russell L. Riley (2000). Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.). The American Presidents. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 83. ISBN 9780815321842.

- ^ a b Russell L. Riley (2000). Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.). The American Presidents. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 87. ISBN 9780815321842.

- ^ Russell L. Riley (2000). Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.). The American Presidents. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 89. ISBN 9780815321842.

- ^ a b c d Russell L. Riley (2000). Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.). The American Presidents. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 88. ISBN 9780815321842.

- ^ a b c Russell L. Riley (2000). Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.). The American Presidents. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 92. ISBN 9780815321842.

- ^ Wayne Cutler (2000). Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.). The American Presidents. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 125. ISBN 9780815321842.

- ^ a b c David J. Bodenhamer (2000). Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.). The American Presidents. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 106. ISBN 9780815321842.

- ^ Wayne Cutler (2000). Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.). The American Presidents. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 128. ISBN 9780815321842.

- ^ William McKinley speech, October 4, 1892, in Boston. William McKinley Papers (Library of Congress)

- ^ List, Friedrich (1841). The National System of Political Economy.

- ^ "cornell.edu".

- ^ "cornell.edu".

- ^ "cornell.edu".

- ^ cornell.edu.

- ^ cornell.edu.

- ^ Gill, William J. Trade Wars Against America: A History of United States Trade and Monetary Policy (1990)

- ^ Lind, Michael: "Free Trade Fallacy" by Michael Lind, New America Foundation. "Like Britain, the U.S. protected and subsidised its industries while it was a developing country, switching to free trade only in 1945, when most of its industrial competitors had been wiped out by the Second World War and the U.S. enjoyed a virtual monopoly in many manufacturing sectors." New America Foundation, – "Free Trade Fallacy" January 2003

- ^ Dr. Ravi Batra, "The Myth of Free Trade": "Unlike most of its trading partners, real wages in the United States have been tumbling since 1973, the first year of the country's switch to laissez-faire." (pp. 126–27) "Before 1973, the U.S. economy was more or less closed and self-reliant, so that efficiency gains in industry generated only a modest price fall, and real earnings soared for all Americans." (pp. 66–67) "Moreover, it turns out that 1973 was the first year in its entire history when the United States became an open economy with free trade." (p. 39)

- ^ Lind, Michael:"The revival of Europe and Japan by the 1970s eliminated these monopoly profits, and the support for free trade of industrial-state voters in the American midwest and northeast declined. Today, support for free-trade globalism in the U.S. comes chiefly from the commodity-exporting south and west and from U.S. multinationals which have moved their factories to low-wage countries like Mexico and China." New America Foundation, "Free Trade Fallacy" January 2003

- ^ List's influences Japan: see "(3) A contrary view: How the World Works Archived 2006-01-17 at the Wayback Machine, by James Fallows"

- ^ "berkeley.edu on List influences of Deng" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-01.

- ^ Frederick Clairmonte, "FRIEDRICH LIST AND THE HISTORICAL CONCEPT OF BALANCED GROWTH", Indian Economic Review, Vol. 4, No. 3 (February 1959), pp. 24–44.

- ^ Mauro Boianovsky, "Friedrich List and the economic fate of tropical countries", Universidade de Brasilia, June 2011, p. 2.

References

[edit]Modern books

[edit]- Batra, Ravi, Dr., The Myth of Free Trade: The pooring of America (1993)

- Boritt, Gabor S., Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream (1994)

- Bourgin, Frank, The Great Challenge: The Myth of Laissez-Faire in the Early Republic (George Braziller Inc., 1989; Harper & Row, 1990)

- Buchanan, Patrick J., The Great Betrayal (1998)

- Chang, Ha-Joon, Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism (Bloomsbury; 2008)

- Croly, Herbert, The Promise of American Life (2005 reprint)

- Curry, Leonard P., Blueprint for Modern America: Nonmilitary Legislation of the First Civil War Congress (1968)

- Dobbs, Lou, Exporting America: Why Corporate Greed is Shipping American Jobs Overseas (2004)

- Dorfman, Joseph, The Economic Mind in American Civilization, 1606–1865 (1947) vol 2

- Dorfman, Joseph, The Economic Mind in American Civilization, 1865–1918 (1949) vol 3

- Dupree, A. Hunter, Science in the Federal Government: A History of Policies and Activities to 1940 (Harvard University Press, 1957; Harper & Row, 1964)

- Foner, Eric, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (1970)

- Faux, Jeff, The Global Class War (2006)

- Frith, Mathew A., "American Protectionist Thought: The Economic Philosophy and Theory of the 19th Century American Protectionists" (2024)

- Frith, Mathew A., "An Outline of 'American Protectionist Thought: The Economic Philosophy and Theory of the 19th Century American Protectionists'" History of Economics Review (2024)

- Gardner, Stephen H., Comparative Economic Systems (1988)

- Gill, William J., Trade Wars Against America: A History of United States Trade and Monetary Policy (1990)

- Goetzmann, William H., Army Exploration in the American West 1803–1863 (Yale University Press, 1959; University of Nebraska Press, 1979)

- Goodrich, Carter, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800–1890 (Greenwood Press, 1960)

- Goodrich, Carter, "American Development Policy: the Case of Internal Improvements," Journal of Economic History, 16 (1956), 449–60. in JSTOR

- Goodrich, Carter, "National Planning of Internal Improvements," Political Science Quarterly, 63 (1948), 16–44. in JSTOR

- Hofstadter, Richard, "The Tariff Issue on the Eve of the Civil War," American Historical Review, 64 (October 1938): 50–55, shows Northern business had little interest in tariff in 1860, except for Pennsylvania which demanded high tariff on iron products

- Howe, Daniel Walker, The Political Culture of the American Whigs (University of Chicago Press, 1979)

- Hudson, Michael, America's Protectionist Takeoff 1815–1914 (2010).

- Jenks, Leland Hamilton, "Railroads as a Force in American Development," Journal of Economic History, 4 (1944), 1–20. in JSTOR

- John Lauritz Larson, Internal Improvement: National Public Works and the Promise of Popular Government in the Early United States (2001)

- Johnson, E.A.J., The Foundations of American Economic Freedom: Government and Enterprise in the Age of Washington (University of Minnesota Press, 1973)

- Lively, Robert A., "The American System, a Review Article," Business History Review, XXIX (March, 1955), 81–96. Recommended starting point.

- Lauchtenburg, William E., Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal 1932–40 (1963)

- Lind, Michael, Hamilton's Republic: Readings in the American Democratic Nationalist Tradition (1997)

- Lind, Michael, What Lincoln Believed: The Values and Convictions of America's Greatest President (2004)

- Mazzucato, Mariana, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths (Anthem Press, 2013)

- Paludan, Philip S, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1994)

- Richardson, Heather Cox, The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War (1997)

- Remini, Robert V., Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union. New York: W. W. Norton Co., 1991

- Roosevelt, Theodore, The New Nationalism (1961 reprint)

- Richardson, Heather Cox. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War (1997)

- Stanwood, Edward, American Tariff Controversies in the Nineteenth Century (1903; reprint 1974), 2 vols., favors protectionism

Older books

[edit]- W. Cunningham, The Rise and Decline of the Free Trade Movement (London, 1904)

- G. B. Curtiss, Protection and Prosperity; and W. H. Dawson, Protection in Germany (London, 1904)

- Alexander Hamilton, Report on the Subject of Manufactures, communicated to the House of Representatives, 5 December 1791

- F. Bowen, American Political Economy (New York, 1875)

- J. B. Byles, Sophisms of Free Trade (London, 1903); G. Byng, Protection (London, 1901)

- H. C. Carey, Principles of Social Science (3 vols., Philadelphia, 1858–59), Harmony of Interests Agricultural, Manufacturing and Commercial (Philadelphia, 1873)

- H. M. Hoyt, Protection v. Free Trade, the scientific validity and economic operation of defensive duties in the United States (New York, 1886)

- Friedrich List, Outlines of American Political Economy (1980 reprint)

- Friedrich List, National System of Political Economy (1994 reprint)

- A. M. Low, Protection in the United States (London, 1904); H. 0. Meredith, Protection in France (London, 1904)

- S. N. Patten, Economic Basis of Protection (Philadelphia, 1890)

- Ugo Rabbeno, American Commercial Policy (London, 1895)

- Ellis H. Roberts, Government Revenue, especially the American System, an argument for industrial freedom against the fallacies of free trade (Boston, 1884)

- R. E. Thompson, Protection to Home Industries (New York, 1886)

- E. E. Williams, The Case for Protection (London, 1899)

- J. P. Young, Protection and Progress: a Study of the Economic Bases of the American Protective System (Chicago, 1900)

- Clay, Henry. The Papers of Henry Clay, 1797–1852. Edited by James Hopkins

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (October 2023) |

- Excerpts of the Report on Manufactures by Alexander Hamilton

- Report on Public Credit I by Alexander Hamilton

- Argument in Favor of the National Bank by Alexander Hamilton

- The Harmony of Interests by Henry C. Carey

- The National System of Political Economy Archived 2009-08-31 at the Wayback Machine by Friedrich List

- Federalist #7, The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton as Publius

- The American System: Speeches on the Tariff Question and Internal Improvements by Congressman Andrew Stewart

- John Bull the Compassionate

- Party Platforms of Republican and Democratic Party's, including links to Third Party's in history.

- "Punchinello", Vol. 1, Issue 8 pg 125 Article from 1870 against the American System

- "Henry Clay: National Socialist" Thomas J. DiLorenzo, Ludwig von Mises Institute

- Vanguard of Expansion: Army Engineers in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1819–1879, by Frank N. Schubert, History Division, Office of the Chief of Engineers, August 1980.

- Swimming Against the Current: The Rise of a Hidden Developmental State in the United States, by Fred Block, Politics & Society, Vol. 35 No. 1, June 2008.

American School (economics)

View on GrokipediaCore Principles and Policies

Protective Tariffs for Infant Industries

Protective tariffs for infant industries formed a cornerstone of the American School's economic strategy, aiming to shield emerging domestic manufacturers from superior foreign competitors until they achieved maturity and competitiveness. Proponents argued that without such barriers, advanced economies like Britain's, bolstered by established capital, skilled labor, and scale advantages, would stifle American industrialization by flooding markets with cheaper imports. This temporary protection was intended to enable learning-by-doing, technological adoption, and infrastructure development, fostering self-sufficiency in manufacturing.[9][10] Alexander Hamilton laid the intellectual groundwork in his Report on the Subject of Manufactures submitted to Congress on December 5, 1791. Hamilton contended that the United States, as a young nation with abundant agriculture but nascent industry, required incentives to diversify beyond raw exports vulnerable to foreign manipulation. While favoring direct bounties over tariffs to avoid distorting consumer prices, he endorsed moderate import duties as a pragmatic tool for revenue and incidental protection, particularly against subsidized foreign goods. Hamilton emphasized that such measures countered Britain's export bounties and navigation acts, which disadvantaged American producers, and cited historical precedents like colonial premiums on indigo and naval stores.[9][11][12] Henry Clay expanded this into the explicit "American System" during the 1810s and 1820s, integrating protective tariffs with internal improvements and a national bank to accelerate industrial growth. Clay advocated tariffs averaging 20-33% on manufactured imports to nurture "infant" sectors like textiles, iron, and machinery, arguing they would generate revenue for infrastructure while building a home market insulated from European volatility. The Tariff Act of 1816, the first explicitly protective measure at rates up to 25% on cotton and woolens, reflected this vision amid post-War of 1812 disruptions to British imports. Subsequent acts in 1824 and 1828 raised duties further, targeting iron, wool, and hemp to support mechanization and defense needs.[13][1][14] Empirical assessments of these tariffs' role in industrial development yield mixed results, with causation often confounded by concurrent factors like immigration, resource endowments, and railroad expansion. In the tinplate sector, the 1890 McKinley Tariff's 70% duties spurred output from near zero to over 100 million pounds annually by 1900, demonstrating accelerated entry and scale-up. However, cost-benefit analyses indicate net welfare losses, as consumer costs and deadweight inefficiencies outweighed producer gains, with protection persisting beyond infancy. Broader 19th-century manufacturing growth—from 8% of GDP in 1820 to 23% by 1890—occurred alongside tariffs averaging 40-50%, but econometric studies attribute expansion primarily to domestic markets and innovation rather than import barriers, which may have retarded efficiency in shielded sectors.[15][16][17] Critics, including Southern agricultural exporters, highlighted tariffs' regressive incidence, raising input costs for cotton and tobacco while benefiting Northern factories, fueling sectional tensions culminating in nullification crises. Economic historians note that prolonged protection entrenched lobbies resistant to liberalization, deviating from the temporary rationale, and question the infant industry justification given the U.S.'s natural advantages in land and labor. While tariffs funded early federal operations—yielding over 90% of revenue pre-income tax—they did not demonstrably cause the era's rapid per capita income growth from $1,257 in 1820 to $4,096 in 1900 (in 1860 dollars), which aligned more closely with institutional stability and capital accumulation.[14][18][19]

Government-Funded Internal Improvements

Government-funded internal improvements formed a core pillar of the American System, advocating federal investment in transportation infrastructure such as roads, canals, and later railroads to integrate national markets, lower shipping costs, and foster economic expansion. Henry Clay, a principal architect of the system, proposed in 1816 and subsequent addresses that revenues from tariffs and public land sales finance these projects, arguing they would bind the republic commercially and militarily while countering European dependencies.[20][21] This approach rested on the view that private capital alone insufficiently addressed vast continental-scale needs, necessitating public outlays to catalyze private follow-on investments. Early federal efforts included the Cumberland Road, authorized in 1806 with initial appropriations of $30,000 for surveying and construction from Cumberland, Maryland, westward, embodying nationalist infrastructure ambitions amid partisan divides.[22] The Bonus Bill of 1817 sought to allocate Second Bank of the United States dividends—estimated at $1.5 million annually—toward broader road and canal works, reflecting post-War of 1812 momentum for national cohesion.[23] However, President James Madison vetoed it on March 3, 1817, his final act in office, citing the absence of explicit constitutional authority under Article I, Section 8, despite his prior calls for such powers at the 1787 Constitutional Convention; he urged a constitutional amendment instead.[24][25] Under Presidents James Monroe and John Quincy Adams, modest advancements persisted, including 1822 congressional approval for presidential surveys of promising routes and extensions of the National Road into Ohio by 1825, funded via general treasury allocations averaging $150,000 yearly in the 1820s.[26] Adams's 1825 address emphasized lighthouses, roads, and canals as essential to "the physical power of the nation," though veto threats from strict constructionists like Martin Van Buren limited scope, with total federal outlays reaching only about $10 million by 1830 amid Southern resistance fearing sectional imbalances.[27] Clay's persistent advocacy in Congress secured incremental victories, such as the 1828 Maysville Road veto by Andrew Jackson—another constitutional rebuff—yet sustained pressure from Whig platforms elevated internal improvements as a partisan hallmark. The policy achieved substantial scale during the Civil War era under Abraham Lincoln, who signed the Pacific Railway Act on July 1, 1862, granting over 130 million acres of public land and $16,000 to $48,000 per mile in loans to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads for a transcontinental line completed in 1869.[28][29] This act, debated since the 1850s, exemplified American School priorities by prioritizing national unity and westward development over fiscal restraint, with federal bonds totaling $64 million by completion; Lincoln justified it as advancing "the public interests" via general welfare provisions, overriding earlier veto precedents.[30] Subsequent Republican administrations extended this through land-grant colleges and river improvements, embedding infrastructure subsidies into postwar growth, though debates on constitutionality lingered without amendment.[31]National Banking and Fiscal Stability

The foundation of national banking in the American School originated with Alexander Hamilton's Report on a National Bank in 1790, which advocated for a central institution to manage federal finances and promote economic stability. The First Bank of the United States, chartered in 1791 with a 20-year term and $10 million capitalization, functioned as the government's fiscal agent by collecting tax revenues, securing deposits, issuing loans to the Treasury, and facilitating inter-state fund transfers.[32] Its notes served as the primary medium for federal tax payments, helping to establish a uniform and credible currency amid post-Revolutionary War economic disarray.[33] Although its charter expired in 1811 due to political opposition, the Bank's operations demonstrated how centralized banking could curb inflationary pressures from state-chartered banks issuing depreciated notes.[34] Henry Clay incorporated national banking into his American System during the 1810s and 1820s, arguing for a renewed national bank to furnish stable credit for manufacturing and infrastructure while preventing the financial instability wrought by unchecked state banking. The Second Bank of the United States, chartered in 1816 with $35 million in capital, resumed the fiscal agent role by redeeming state banknotes in specie, stabilizing the currency supply after the War of 1812's disruptions.[35] Clay and fellow Whigs viewed the institution as essential for fiscal discipline, enabling the government to fund internal improvements without resorting to excessive taxation or borrowing from foreign sources.[36] President Andrew Jackson's veto of the Bank's recharter in 1832 and subsequent dissolution precipitated the Panic of 1837, underscoring the risks of decentralized banking and reinforcing American School proponents' case for federal oversight.[37] In the 1860s, Republican advocates of the American System, including Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, enacted the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 to create a network of federally chartered banks issuing notes backed by U.S. government bonds, thereby unifying the currency and financing Civil War expenditures exceeding $3 billion.[38] These acts required national banks to hold reserves against deposits and purchase federal bonds as security for note issuance, which totaled over $300 million by 1865 and reduced circulation of unreliable state banknotes through a 10% excise tax imposed in 1865.[39] The system enhanced fiscal stability by linking banknote supply to government debt, facilitating Treasury borrowing at lower rates and mitigating wartime inflation, though inelastic currency reserves contributed to later panics until the Federal Reserve's creation in 1913.[40] Proponents maintained that such mechanisms embodied causal principles of monetary order, prioritizing national cohesion over laissez-faire fragmentation.Historical Origins and Advocacy

Hamiltonian Foundations (1790s)

Alexander Hamilton, appointed the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury in September 1789, laid the foundational economic policies of the American School through a series of reports to Congress in the early 1790s. These initiatives emphasized establishing national credit, fostering financial institutions, and promoting manufacturing to achieve economic independence from foreign powers, particularly Britain. Hamilton's vision prioritized a strong federal government capable of funding public debts, stabilizing currency, and protecting nascent industries via targeted interventions, diverging from agrarian ideals favoring laissez-faire agriculture.[41][10] In his First Report on Public Credit, submitted January 9, 1790, Hamilton proposed redeeming the federal and state debts at full face value, totaling approximately $54 million for continental securities and $25 million in state debts, to restore public confidence and integrate the states under federal authority. He advocated assuming state Revolutionary War debts to bind creditors to the national government and prevent discrimination between original holders and speculators, funding this through import tariffs averaging 8-10% and an excise on distilled spirits yielding about $1 million annually. Congress passed the Funding Act in August 1790 and Assumption Act in the same month as part of the Compromise of 1790, establishing a sinking fund managed by the Treasury to gradually redeem the debt.[41][42][43] Hamilton's Report on a National Bank, delivered December 13, 1790, recommended chartering a Bank of the United States with $10 million in capital, 20% subscribed by the government and the rest by private investors, to handle government deposits, issue notes, and facilitate commerce by providing stable credit and discounting commercial paper. Modeled partly on the Bank of England but with limited federal ownership to avoid direct control, the bank aimed to monetize debt and support fiscal operations without relying on state banks prone to instability. Despite constitutional debates, President Washington signed the bill into law February 25, 1791, operationalizing the institution by late 1791.[44][32][45] The Report on the Subject of Manufactures, presented December 5, 1791, argued that reliance on agriculture alone exposed the U.S. to foreign supply manipulations and limited wealth creation, advocating diversification into manufacturing through protective tariffs on imports, bounties for key industries like textiles and iron, and exemptions from duties on raw materials. Hamilton cited Europe's success in shielding infant industries, estimating that premiums could spur innovations yielding higher productivity and employment, with tariffs generating revenue while gradually reducing dependence on subsidies. Though Congress did not immediately enact protective measures beyond revenue tariffs under the Tariff Act of 1789 and subsequent duties averaging 12-15% by 1792, Hamilton's framework influenced later policy by demonstrating that government action could catalyze industrial growth against free-trade orthodoxy.[9][10][46]Henry Clay's American System (1810s–1830s)

Henry Clay, a prominent statesman and Speaker of the House, formulated the American System as an economic policy framework in the aftermath of the War of 1812, emphasizing national self-sufficiency amid the demonstrated vulnerabilities of reliance on foreign trade.[1] First articulated in detail during his March 30–31, 1824, speech in the House of Representatives, the system integrated protective tariffs to shield emerging domestic industries from British competition, a national bank to stabilize currency and credit, and federal funding for internal improvements such as roads and canals to enhance interstate commerce and market integration.[47] Clay argued that these measures would foster industrial growth, generate revenue for infrastructure, and bind the diverse regions of the United States into a cohesive economic union, countering the agrarian interests dominant in the South and the free-trade doctrines of figures like John C. Calhoun.[48] In the 1810s, Clay's advocacy gained traction during the "Era of Good Feelings," with the Tariff of 1816 marking the initial legislative success of protective duties, imposing average rates of about 25% on imports to bolster nascent manufacturing sectors hit hard by wartime disruptions.[1] As Speaker from 1815 to 1820, Clay supported the measure, which passed Congress on April 27, 1816, yielding duties that averaged 20–25% and provided federal revenue while encouraging textile and iron production in the North and West.[49] Efforts to fund internal improvements followed, including the Bonus Bill of 1817, which proposed using Second Bank of the United States dividends for transportation projects but was vetoed by President James Madison on March 3, 1817, on constitutional grounds, limiting federal involvement despite Clay's push for national roads like the Cumberland Road extension.[50] The 1820s saw Clay elevate the American System as a cornerstone of National Republican policy, with the Tariff of 1824 raising rates further to an average of 37% on dutiable imports, aimed at protecting iron, woolens, and hemp industries, though it deepened sectional tensions.[1] By the 1830s, as leader of the Whig Party formed in opposition to Andrew Jackson, Clay defended the system against Democratic assaults, notably during the Bank War where Jackson vetoed the Second Bank's recharter on July 10, 1832, fracturing the financial stability Clay deemed essential.[48] The Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833, triggered by the 1828 Tariff of Abominations with rates up to 50%, prompted Clay to engineer the Compromise Tariff of 1833 on March 2, which gradually reduced duties over a decade to 20% by 1842, preserving the union but diluting protective elements and highlighting the system's precarious balance between Northern industrial interests and Southern export reliance.[50] Despite partial implementations, such as ongoing Cumberland Road construction funded by land sales, the era underscored the American System's role in promoting economic nationalism, though federal funding remained inconsistent due to constitutional debates and vetoes totaling over a dozen internal improvement bills between 1817 and 1830.[51]

Whig and Republican Promotion (1840s–1860s)

The Whig Party, building on Henry Clay's American System, intensified promotion of protective tariffs and internal improvements during the 1840s following their 1840 electoral victory. With control of Congress after the 1840 elections, Whigs enacted the Tariff of 1842 on August 30, which raised average ad valorem duties from 20% under the 1833 Compromise Tariff to approximately 32%, aiming to revive manufacturing and revenue depleted by prior reductions.[52] This protectionist measure reversed Democratic low-tariff policies, shielding nascent industries from British competition despite President John Tyler's initial reluctance, as he ultimately signed the bill amid party pressure.[7] Whigs persistently advocated federal funding for infrastructure, introducing numerous bills for rivers, harbors, and roads, though Tyler vetoed key proposals like the 1842 Distribution Bill and river-and-harbor improvements citing constitutional limits on federal spending.[53] Henry Clay, the party's leading exponent, campaigned on these principles in the 1844 presidential election, emphasizing tariffs to foster domestic industry and internal improvements to enhance commerce, though defeat by James K. Polk halted immediate advances.[54] Abraham Lincoln, serving as a Whig congressman from 1847 to 1849, echoed this agenda, supporting navigation and harbor bills while critiquing Polk's vetoes of similar Democratic-era measures.[55] As the Whig Party fractured over slavery by the early 1850s, its economic doctrines transitioned to the newly formed Republican Party in 1854, comprising former Whigs, Free Soilers, and anti-slavery Democrats who retained commitment to protectionism and development. The 1856 Republican platform explicitly endorsed a protective tariff to promote American labor and industry, alongside federal support for a Pacific railroad, homestead lands, and river improvements.[56] In 1860, the platform reaffirmed these policies, advocating transcontinental rail, mail services, and tariffs to counter foreign pauper labor, aligning with Lincoln's longstanding admiration for Clay, whom he eulogized in 1852 as embodying principled statesmanship in advancing national economy.[57][58] Lincoln, declaring in 1860 that his tariff views remained unchanged from Clay's era, positioned Republicans as heirs to Whig economic nationalism, prioritizing industrial growth over laissez-faire doctrines amid sectional tensions.[7] This continuity ensured the American School's principles endured into the Civil War era, with platforms framing tariffs not merely as revenue but as tools for economic independence and worker prosperity.[59]Implementation and Expansion

Lincoln Administration and Civil War Era (1861–1865)

The Lincoln administration implemented key elements of the American School through wartime legislation that promoted protective tariffs, national banking, and internal improvements, aligning with Republican economic priorities to strengthen industrial capacity and fiscal stability amid the Civil War.[60] These measures, rooted in Hamiltonian and Clayite principles, shifted federal policy toward active government intervention to foster manufacturing, infrastructure, and a unified currency system, providing both war financing and long-term economic development.[61] Protective tariffs were elevated via the Morrill Tariff Act, enacted on March 2, 1861, just before Lincoln's inauguration, which raised average duties from approximately 20% to 47%, primarily to generate revenue—tariffs had supplied over 90% of federal income pre-war—and shield nascent industries from foreign competition.[61] [62] Lincoln, a proponent of high tariffs since his congressional days, endorsed this policy, and subsequent wartime revenue acts in 1862 and 1864 further increased rates to fund military expenditures exceeding $3 billion by war's end, while reinforcing protection for Northern manufacturing against British imports.[60] [63] The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864, signed by Lincoln on February 25, 1863, and June 3, 1864, established a system of federally chartered banks to issue a uniform national currency backed by U.S. government bonds, addressing the pre-war chaos of diverse state banknotes and enabling efficient war bond sales totaling over $2.5 billion.[38] [64] This framework, overseen by the newly created Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, centralized fiscal authority, reduced currency depreciation risks, and laid groundwork for monetary stability, embodying the American School's emphasis on a strong national financial system over decentralized banking.[65] Internal improvements advanced through acts like the Pacific Railway Act of July 1, 1862, which authorized federal land grants—totaling about 130 million acres—and loans up to $16,000 per mile for constructing the first transcontinental railroad by the Union Pacific and Central Pacific companies, aiming to integrate markets and bolster military logistics.[28] [29] Complementing this, the Homestead Act of May 20, 1862, distributed 160-acre parcels of public land to settlers who improved and resided on them for five years, facilitating agricultural expansion and westward migration that supported industrial growth by securing food supplies and raw materials.[66] These initiatives, despite wartime constraints, exemplified government-directed infrastructure investment to enhance connectivity and productivity, core to the American School's vision of national economic cohesion.[67]Postwar Republican Dominance (1865–1890s)

Following the Union victory in the Civil War, the Republican Party maintained dominance in national politics through the late 19th century, controlling the presidency from 1869 to 1885 and again from 1889 to 1893, alongside majorities in Congress that enabled sustained implementation of protective economic policies.[68] With the secession of Southern Democrats removed, Republicans faced minimal opposition to high tariffs and infrastructure investments, viewing them as essential for fostering domestic manufacturing and national cohesion.[69] This era marked the American System's maturation into a framework prioritizing industrial protection over agrarian free-trade interests. Protective tariffs remained a cornerstone, with postwar rates averaging 40-50% on dutiable imports, far exceeding prewar levels and shielding emerging sectors like steel and textiles from European competition.[70] The Morrill Tariff of 1861, which had raised averages to approximately 47%, was upheld and adjusted upward to finance reconstruction while promoting "infant industries," as Republicans argued such measures generated broader economic progress rather than mere special-interest favors.[69] By 1890, under Republican leadership, the McKinley Tariff further elevated rates to nearly 50% on many goods, including wool and tin, aiming to bolster American producers amid global competition; though criticized for inflating consumer prices, proponents cited revenue surpluses exceeding $100 million annually by the mid-1880s as evidence of fiscal viability.[71] Internal improvements received substantial federal backing, exemplified by the completion of the first transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah, which connected eastern and western markets under subsidies from the 1862 Pacific Railway Act.[72] Republican administrations allocated over 180 million acres in land grants to railroad companies by the 1870s, alongside loans totaling $64 million, accelerating freight transport and settlement; annual federal outlays for rivers, harbors, and roads rose from under $4 million prewar to significantly higher levels by the 1880s, with $103 million spent on public works from 1865 to 1873 alone.[73] [74] These investments prioritized Northern and Western connectivity, knitting industrial heartlands while generating returns through increased commerce, though Southern regions received disproportionately less due to Reconstruction priorities.[74] The national banking system expanded robustly, with the number of chartered national banks growing from about 1,700 in 1866 to over 3,400 by 1890, their assets surging to support industrial credit amid rapid urbanization.[75] Enacted during the war but scaled postwar, this framework issued a uniform currency backed by federal bonds, reducing regional banking instability and channeling capital to manufacturing; studies indicate counties gaining national bank access saw per capita manufacturing output rise by roughly $310 (equivalent to $8,620 in 2018 dollars) between 1880 and 1890.[76] Republicans defended the system against Democratic calls for state bank revival, emphasizing its role in curbing inflation and enabling the monetary stability needed for long-term growth.[77] By the 1890s, these intertwined policies had entrenched Republican economic orthodoxy, though emerging agrarian discontent foreshadowed challenges.Evolution into Progressive Era Policies (1900s)

The Republican administrations of the early 1900s upheld the American System's commitment to protective tariffs as a bulwark for domestic industry, with the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 maintaining average ad valorem rates near 40 percent despite campaign promises of downward revision, thereby shielding manufacturers from foreign competition while generating federal revenue.[78] President Theodore Roosevelt, a proponent of economic nationalism rooted in Hamiltonian and Clayite traditions, advocated for tariffs that advanced national interests over pure revenue collection, arguing they benefited the broader populace when aligned with regulatory oversight to curb monopolistic abuses.[79][80] This continuity reflected the system's evolution amid industrial maturation, where protectionism shifted from nurturing infant industries to sustaining mature sectors against global rivals, though it drew criticism from tariff revisionists for fostering inefficiencies.[81] Monetary policy saw a pivotal revival of national banking principles with the Federal Reserve Act of December 23, 1913, establishing a decentralized central bank to mitigate panics like that of 1907 and ensure elastic currency, echoing Alexander Hamilton's First Bank of the United States as a mechanism for fiscal stability and economic coordination.[82] Proponents framed the Fed as fulfilling the American System's emphasis on a unified national financial framework, free from partisan excess yet capable of countering decentralized banking's vulnerabilities, a goal long championed by Whigs and Republicans against Jacksonian decentralization.[32] Enacted under Woodrow Wilson following the Aldrich Plan's Republican groundwork, it marked an institutional adaptation rather than wholesale departure, prioritizing systemic resilience over laissez-faire fragmentation.[36] Internal improvements expanded under progressive auspices, with Theodore Roosevelt's Newlands Reclamation Act of June 17, 1902, authorizing federal funding for western irrigation and dam projects—totaling over 20 major initiatives by 1910—to harness arid lands for agriculture and settlement, directly extending Clay's vision of government-facilitated infrastructure for territorial cohesion and productivity.[83] This built on 19th-century precedents like the Morrill Land-Grant Acts, integrating conservationist elements such as national forests (established via the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, expanded under Roosevelt) to sustain resource-based development, thereby blending American System developmentalism with emerging regulatory imperatives for sustainable growth.[27] Such policies underscored the era's transition toward a more activist federal role, where interventionist tools once confined to protection and banking now encompassed antitrust enforcement and public works, adapting core tenets to address urbanization and corporate concentration without abandoning national economic prioritization.Theoretical Rationale

First-Principles Economic Reasoning

The American School's advocacy for protective tariffs rested on the recognition that emerging domestic industries in a resource-rich but capital-scarce nation face inherent disadvantages against established foreign competitors, necessitating temporary barriers to allow for learning-by-doing and scale economies that reduce unit costs over time.[9] This reasoning derives from the fundamental economic principle that productivity in manufacturing arises from specialization and division of labor, which require sustained production volumes to develop; without protection, imports priced at mature foreign costs would preclude domestic entry, perpetuating dependence on raw exports subject to price volatility and foreign control.[84] Hamilton argued that manufactures diversify economic output, mitigating agriculture's cyclical risks and enhancing overall revenue through value-added processing, as labor and capital yield higher returns when applied to finished goods rather than primary products alone.[9] A national banking system was deemed essential to furnish a uniform currency and credit mechanism, addressing the causal reality that fragmented state banks engender instability, speculation, and inadequate long-term lending for infrastructure and industry.[10] From basic principles of exchange, reliable money facilitates capital accumulation by reducing transaction uncertainties and enabling fractional-reserve lending under centralized oversight, which private markets in nascent economies underprovide due to coordination failures and moral hazard risks.[85] Proponents like Clay extended this to federal chartering, positing that a sound currency underpins commerce's expansion, as evidenced by the Second Bank of the United States' role in stabilizing post-War of 1812 finances.[48] Internal improvements, such as roads and canals, embodied the principle that physical connectivity lowers transport costs and integrates regional markets, generating positive externalities like faster goods movement and knowledge diffusion that private entities undervalue due to non-excludable benefits.[48] Clay's rationale emphasized that government investment in these public goods accelerates national cohesion and productivity, countering the laissez-faire assumption of spontaneous market provision in frontier conditions where high initial costs deter private action.[48] Collectively, these policies aimed at self-reliant growth, prioritizing causal chains of domestic capability-building over abstract comparative advantage, which Hamilton critiqued as insufficient for nations lacking diversified skills and capital to exploit static endowments.[9]Critique of Laissez-Faire and Free Trade Orthodoxy

Proponents of the American School, beginning with Alexander Hamilton, contended that laissez-faire principles, which minimize government intervention in markets, fail to account for the vulnerabilities of emerging economies dependent on foreign trade. In his Report on the Subject of Manufactures (December 5, 1791), Hamilton asserted that a purely agricultural nation risks supply disruptions during wars or embargoes, as evidenced by colonial America's exposure to British restrictions, and argued that manufacturing diversification enhances prosperity through expanded markets and skill development.[9] He dismissed the sufficiency of natural advantages under free trade, noting that "superior skill and arrangements are decisive causes of success" in competition, requiring temporary protective measures like tariffs or bounties to overcome initial disadvantages against established foreign producers.[9] Henry Clay extended this critique in the 1820s and 1830s, portraying free trade orthodoxy—rooted in Adam Smith's advocacy of unrestricted exchange—as a mechanism for perpetuating British dominance over American resources. In his 1832 Senate speech on the American System, Clay warned that unrestricted imports would flood U.S. markets with British goods, stifling domestic manufactures and reducing the nation to exporting raw materials like cotton and tobacco, mirroring pre-independence colonial patterns where Britain exported 80% of its cotton imports as finished textiles by 1830.[1] He rejected the Ricardian comparative advantage doctrine, arguing it assumes static conditions and ignores how protectionism enables technological catch-up; for instance, Clay cited Britain's own pre-1846 Corn Laws and Navigation Acts as hypocritical precedents for its free-trade advocacy, which served to maintain its manufacturing lead while advocating dependency for rivals.[86] Henry C. Carey, a leading 19th-century theorist of the tradition, further assailed laissez-faire for promoting class antagonism and economic stagnation through doctrines like Ricardo's rent theory, which he claimed justified land monopolies and low wages incompatible with republican values. In Principles of Social Science (1858), Carey argued that free trade fragments societies into antagonistic interests—capital versus labor, agriculture versus industry—contrary to harmonious national development, and empirically linked Britain's post-1846 free-trade shift to rising pauperism and emigration, with over 2 million Irish fleeing famine-exacerbated conditions by 1851.[87] He advocated protective tariffs not as eternal but as tools for value-added production, critiquing Smithian laissez-faire for overlooking positive feedbacks like wage growth from diversified industry, which U.S. tariff policies from 1816 onward demonstrably fostered by raising manufacturing output from 8% of GDP in 1810 to 32% by 1860.[88] The American School's broader objection to free trade orthodoxy emphasized its neglect of national sovereignty and long-term causality: unrestricted commerce favors nations with mature industries, trapping others in low-value exports and vulnerability to foreign policy leverage, as seen in Britain's 1807–1812 Orders in Council that halved U.S. exports to 22 million pounds sterling.[89] Proponents like Clay and Carey posited that government-directed investments in infrastructure and banking counteract market failures in capital-scarce frontiers, where private laissez-faire yields underinvestment; for example, Clay's 1824 tariff advocacy highlighted how duties funded canals and roads, interconnecting regions to multiply internal trade beyond export reliance, with U.S. domestic commerce surpassing foreign by the 1830s.[1] This framework prioritized causal realism—industry begetting skills, markets, and defense capacity—over abstract equilibrium models, viewing pure free trade as theoretically elegant but empirically ruinous for non-dominant powers.Empirical Outcomes

Contributions to Industrialization and Growth

The protective tariffs advocated by proponents of the American School shielded emerging U.S. industries from low-cost imports, particularly from Britain, allowing domestic manufacturers to invest in production capacity and innovation without immediate foreign undercutting. Between 1860 and 1900, under sustained high tariff rates averaging 40-45% on dutiable imports, the United States increased its share of global manufacturing output from 7.2% to 23.6%, surpassing Britain as the world's leading industrial producer by the late 1890s.[90] This protection enabled sectors like textiles, iron, and machinery to scale up, with empirical correlations showing output expansion in tariff-supported industries during periods of elevated duties.[16] Internal improvements, including federally subsidized canals, roads, and railroads aligned with American System principles, dramatically lowered transportation costs and expanded market access, spurring industrial demand for raw materials and distribution of finished goods. The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, exemplified this by reducing freight rates from Buffalo to New York City from $100 per ton to under $9, facilitating a surge in agricultural exports from the Midwest and industrial imports to growing factories, which in turn boosted New York's economic dominance and national westward settlement.[91] By integrating regional economies into a cohesive national market, such infrastructure investments reduced logistics barriers that had previously constrained manufacturing scalability, contributing to broader economic integration and productivity gains in transport-dependent industries.[92] The reestablishment of a national banking framework through the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 provided a stable monetary system and credit channels essential for industrial financing, mitigating the fragmented state banking panics of the pre-Civil War era. This system encouraged the chartering of over 700 new national banks by 1866, channeling capital toward manufacturing ventures and wartime production needs, while standardizing currency circulation to support large-scale enterprise.[93] Together, these elements of the American School fostered conditions for sustained capital accumulation and technological adoption, underpinning the U.S. transition from agrarian dominance to industrial leadership by 1900.[94]Quantifiable Economic Achievements