Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

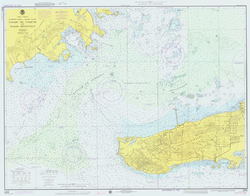

Nautical chart

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

A nautical chart or hydrographic chart is a graphic representation of a sea region or water body and adjacent coasts or banks. Depending on the scale of the chart, it may show depths of water (bathymetry) and heights of land (topography), natural features of the seabed, details of the coastline, navigational hazards, locations of natural and human-made aids to navigation, information on tides and currents, local details of the Earth's magnetic field, and human-made structures such as harbours, buildings, and bridges. Nautical charts are essential tools for marine navigation; many countries require vessels, especially commercial ships, to carry them. Nautical charting may take the form of charts printed on paper (raster navigational charts) or computerized electronic navigational charts. Recent technologies have made available paper charts which are printed "on demand" with cartographic data that has been downloaded to the commercial printing company as recently as the night before printing. With each daily download, critical data such as Local Notices to Mariners are added to the on-demand chart files so that these charts are up to date at the time of printing.

Data sources

[edit]Nautical charts are based on hydrographic surveys and bathymetric surveys. As surveying is laborious and time-consuming, hydrographic data for many areas of sea may be dated and are sometimes unreliable. Depths are measured in a variety of ways. Historically the sounding line was used. In modern times, echo sounding is used for measuring the seabed in the open sea. When measuring the safe depth of water over an entire obstruction, such as a shipwreck, the minimum depth is checked by sweeping the area with a length of horizontal wire. All depths on charts is measured with respect to a datum/reference level. This ensures that difficult to find projections, such as masts, do not present a danger to vessels navigating over the obstruction.

Publication

[edit]Nautical charts are issued by power of the national hydrographic offices in many countries. These charts are considered "official" in contrast to those made by commercial publishers. Many hydrographic offices provide regular, sometimes weekly, manual updates of their charts through their sales agents. Individual hydrographic offices produce national chart series and international chart series. Coordinated by the International Hydrographic Organization, the international chart series is a worldwide system of charts ("INT" chart series), which is being developed with the goal of unifying as many chart systems as possible.

There are also commercially published charts, some of which may carry additional information of particular interest, e.g. for yacht skippers.

Chart correction

[edit]The nature of a waterway depicted by a chart may change, and artificial aids to navigation may be altered at short notice. Therefore, old or uncorrected charts should never be used for navigation. Every producer of nautical charts also provides a system to inform mariners of changes that affect the chart. In the United States, chart corrections and notifications of new editions are provided by various governmental agencies by way of Notice to Mariners, Local Notice to Mariners, Summary of Corrections, and Broadcast Notice to Mariners. In the U.S., NOAA also has a printing partner who prints the "POD" (print on demand) NOAA charts, and they contain the very latest corrections and notifications at the time of printing. To give notice to mariners, radio broadcasts provide advance notice of urgent corrections.

A good way to keep track of corrections is with a Chart and Publication Correction Record Card system. Using this system, the navigator does not immediately update every chart in the portfolio when a new Notice to Mariners arrives, instead creating a card for every chart and noting the correction on this card. When the time comes to use the chart, he pulls the chart and chart's card, and makes the indicated corrections on the chart. This system ensures that every chart is properly corrected prior to use. A prudent mariner should obtain a new chart if he has not kept track of corrections and his chart is more than several months old.

Various Digital Notices to Mariners systems are available on the market such as Digitrace, Voyager, or ChartCo, to correct British Admiralty charts as well as NOAA charts. These systems provide only vessel relevant corrections via e-mail or web downloads, reducing the time needed to sort out corrections for each chart. Tracings to assist corrections are provided at the same time.

The Canadian Coast Guard produces the Notice to Mariners publication which informs mariners of important navigational safety matters affecting Canadian Waters. This electronic publication is published on a monthly basis and can be downloaded from the Notices to Mariners (NOTMAR) Web site. The information in the Notice to Mariners is formatted to simplify the correction of paper charts and navigational publications.

Various and diverse methods exist for the correction of electronic navigational charts.

Limitations

[edit]In 1973 the cargo ship MV Muirfield (a merchant vessel named after Muirfield, Scotland) struck an unknown object in the Indian Ocean in waters charted at a depth of greater than 5,000 metres (16,404 ft), resulting in extensive damage to her keel.[1] In 1983, HMAS Moresby, a Royal Australian Navy survey ship, surveyed the area where Muirfield was damaged, and charted in detail a previously unsuspected hazard to navigation, the Muirfield Seamount. The dramatic accidental discovery of the Muirfield Seamount is often cited as an example of limitations in the vertical geodetic datum accuracy of some offshore areas as represented on nautical charts, especially on small-scale charts.

A similar incident involving a passenger ship occurred in 1992 when the Cunard liner Queen Elizabeth 2 struck a submerged rock off Block Island in the Atlantic Ocean.[2] In November 1999, the semi-submersible, heavy-lift ship Mighty Servant 2 capsized and sank after hitting an uncharted single underwater isolated pinnacle of granite off Indonesia. Five crew members died and Mighty Servant 2 was declared a total loss.[3] More recently, in 2005 the submarine USS San Francisco ran into an uncharted seamount (sea mountain) about 560 kilometres (350 statute miles) south of Guam at a speed of 35 knots (40.3 mph; 64.8 km/h), sustaining serious damage and killing one seaman. In September 2006 the jack-up barge Octopus ran aground on an uncharted sea mount within the Orkney Islands (United Kingdom) while being towed by the tug Harold. £1M worth of damage was caused to the barge and delayed work on the installation of a tidal energy generator prototype. As stated in the Mariners Handbook and subsequent accident report: "No chart is infallible. Every chart is liable to be incomplete".[4]

Map projection, positions, and bearings

[edit]

Historically the first projection, invented by Marinus of Tyre ca. AD 100 according to Ptolemy, was what is now called equirectangular projection (historically called plane chart, plate carrée, Portuguese: carta plana quadrada). While it is very convenient for small seas like the Aegean, it is unsuitable for seas larger than Mediterranean or an open ocean, even though early explorers had to use it for want of a better.

The Mercator projection is now used on the vast majority of nautical charts. Since the Mercator projection is conformal, that is, bearings in the chart are identical to the corresponding angles in nature, courses plotted on the chart may be used directly as the course-to-steer at the helm.

The gnomonic projection is used for charts intended for plotting of great circle routes. NOAA uses the polyconic projection for some of its charts of the Great Lakes, at both large and small scales.[5]

Positions of places shown on the chart can be measured from the longitude and latitude scales on the borders of the chart, relative to a geodetic datum such as WGS 84.

A bearing is the angle between the line joining the two points of interest and the line from one of the points to the north, such as a ship's course or a compass reading to a landmark. On nautical charts, the top of the chart is always true north, rather than magnetic north, towards which a compass points. Most charts include a compass rose depicting the variation between magnetic and true north.

However, the use of the Mercator projection has drawbacks. This projection shows the lines of longitude as parallel. On the real globe, the lines of longitude converge as they approach the north or south pole. This means that east–west distances are exaggerated at high latitudes. To keep the projection conformal, the projection increases the displayed distance between lines of latitude (north–south distances) in proportion; thus a square is shown as a square everywhere on the chart, but a square on the Arctic Circle appears much bigger than a square of the same size at the equator. In practical use, this is less of a problem than it sounds. One minute of latitude is, for practical purposes, a nautical mile. Distances in nautical miles can therefore be measured on the latitude gradations printed on the side of the chart.[6]

Electronic and paper charts

[edit]

Conventional nautical charts are printed on large sheets of paper at a variety of scales. Mariners will generally carry many charts to provide sufficient detail for the areas they might need to visit. Electronic navigational charts, which use computer software and electronic databases to provide navigation information, can augment or in some cases replace paper charts, though many mariners carry paper charts as a backup in case the electronic charting system fails.

Details on a nautical chart

[edit]Many countries' hydrographic agencies publish a "Chart 1", which explains all of the symbols, terms and abbreviations used on charts that they produce for both domestic and international use. Each country starts with the base symbology specified in IHO standard INT 1, and is then permitted to add its own supplemental symbologies to its domestic charts, which are also explained in its version of Chart 1. Ships are typically required to carry copies of Chart 1 with their paper charts.

Labels

[edit]

Nautical charts must be labeled with navigational and depth information. There are a few commercial software packages that do automatic label placement for any kind of map or chart. Modern systems render electronic charts consistent with the IHO S-52 specification, issued by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO).[7]

Pilotage information

[edit]

The chart uses symbols to provide pilotage information about the nature and position of features useful to navigators, such as sea bed information, sea mark, and landmarks. Some symbols describe the sea bed with information such as its depth, materials as well as possible navigational hazards such as shipwrecks. Other symbols show the position and characteristics of navigational aids such as buoys, lights, lighthouses, coastal and land features and structures that are useful for position fixing. The abbreviation "ED" is commonly used to label geographic locations whose existence is doubtful.

Colours distinguish between human-made features, dry land, sea bed that dries with the tide, and seabed that is permanently underwater and indicate water depth.

Depths and heights

[edit]

Depths which have been measured are indicated by the numbers shown on the chart. Depths on charts published in most parts of the world use metres. Older charts, as well as those published by the United States government, may use feet or fathoms. Depth contour lines show the shape of underwater relief. Coloured areas of the sea emphasise shallow water and dangerous underwater obstructions. Depths are measured from the chart datum, which is related to the local sea level. The chart datum varies according to the standard used by each national hydrographic office. In general, the trend is towards using lowest astronomical tide (LAT), the lowest tide predicted in the full tidal cycle, but in non-tidal areas and some tidal areas Mean Sea Level (MSL) is used.

Heights, e.g. a lighthouse, are generally given relative to mean high water spring (MHWS). Vertical clearances, e.g. below a bridge or cable, are given relative to highest astronomical tide (HAT). The chart will indicate what datum is in use.

The use of HAT for heights and LAT for depths, means that the mariner can quickly look at the chart to ensure that they have sufficient clearance to pass any obstruction, though they may have to calculate height of tide to ensure their safety.

Tidal information

[edit]Tidal races and strong currents have special chart symbols. Tidal flow information may be shown on charts using tidal diamonds, indicating the speed and bearing of the tidal flow during each hour of the tidal cycle.

See also

[edit]- Aeronautical chart

- Automatic label placement

- Admiralty chart

- Bathymetric chart

- European Atlas of the Seas

- Nautical star

- Navigation room

- Portolan chart

- Dutch maritime cartography in the Age of Discovery (First printed atlas of nautical charts, 1584)

Further reading

[edit]- Calder, Nigel (2008). How to Read a Nautical Chart. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-159287-1.

References

[edit]- ^ Calder, Nigel. How to Read a Navigational Chart: A Complete Guide to the Symbols, Abbreviations, and Data Displayed on Nautical Charts. International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press, 2002.

- ^ British Admiralty. The Mariner's Handbook. 1999 edition, page 23.

- ^ "Maritime Casualties 1999 And Before". The Cargo Letter. 2007. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ Marine Investigation Accident Branch (2007) Report Number 18/2007.

- ^ See, for example, NOAA 14860 - Lake Huron 1:500,000 and NOAA 14853 Detroit River 1:15,000.

- ^ "Nautical charts". sailingissues.com.

- ^ "Specifications for chart content and display aspects of ECDIS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-30.

External links

[edit]- The Medieval and Early Modern Nautical Chart: Birth, Evolution and Use, Lisbon-based ERC-funded academic project. They develop and maintain the MEDEA-CHART Database, a sophisticated search engine and aggregator of early nautical charts data.

- Online version of Chart No.1 with "Symbols, Abbreviations and Terms" used in nautical charts

- Portolan Chart of Gabriel de Vallseca, 1439

- The short film "Reading Charts (April 6, 1999)" is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Nautical charts available online (Nautical Free)

- Online Nautical Charts Viewer

Nautical chart

View on GrokipediaHistory and Evolution

Early Charts and Precursors

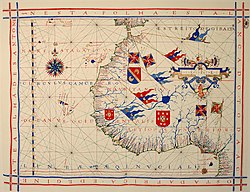

The earliest precursors to nautical charts emerged in ancient civilizations, laying foundational concepts for representing geographic and maritime spaces. The Babylonian World Map, inscribed on a clay tablet around 600 BCE, represents one of the oldest known cartographic efforts, depicting a schematic worldview centered on Babylon with surrounding regions and the Euphrates River, though it focused on terrestrial features rather than navigation.[10] In the 2nd century CE, Claudius Ptolemy's Geographia advanced this tradition by compiling coordinates for over 8,000 localities, including coastal outlines derived from maritime itineraries like the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, which converted sailing distances into latitudinal and longitudinal positions to aid trade routes in the Indian Ocean and Atlantic.[11] These works influenced subsequent marine cartography by introducing systematic projection methods and emphasizing coastal accuracy, despite their limitations in observational data. By the medieval period, portolan charts marked a significant evolution in practical nautical mapping, originating in Italy during the late 13th century. Likely developed in ports like Pisa or Genoa, the earliest surviving example, the Carte Pisane (c. 1290–1300), features detailed Mediterranean coastlines with exaggerated capes and islands, prioritizing inshore navigation over inland topography.[12] These manuscript charts, produced through the 16th century, incorporated networks of rhumb lines—32 radiating directions color-coded for winds and fractions—to facilitate compass-based sailing, while omitting latitude and longitude grids in favor of estimated distances and place-names aligned perpendicular to shores.[13] Over 140 examples from the 15th century alone demonstrate their precision, unmatched until the 18th century, and reflect Italian and Catalan styles that expanded to include Atlantic islands and parts of Africa by the 1400s.[12] The Age of Discovery, spanning the 15th and 16th centuries, transformed rudimentary charts into tools for global exploration, driven by maritime powers like Portugal and Spain. Portuguese navigators, building on astronomical methods such as the Regimento do Sol for latitude determination, produced detailed coastal surveys during voyages like Vasco da Gama's to India (1497–1499), integrating periplus data into manuscript maps that supported trade routes to Africa and Asia.[14] Similarly, Spanish expeditions, including Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation (1519–1522), employed cosmographers like Andrés de San Martín to chart Pacific and Atlantic coasts using lunar observations for longitude estimates, though inaccuracies persisted.[14] A pivotal advancement came from Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator, whose 1569 world map introduced a conformal cylindrical projection that preserved angles for rhumb lines, enabling sailors to plot constant compass bearings on flat charts despite distortions in high latitudes.[7] This innovation, tailored for oceanic navigation, significantly influenced chart design by prioritizing directional accuracy over proportional land areas, though its full navigational potential was limited by 16th-century data constraints.[15] The 16th century witnessed a shift from exclusive manuscript production to printed nautical charts, broadening access and standardizing formats. In Italy and the Low Countries, woodblock printing enabled the reproduction of portolan-style maps, while English efforts lagged until figures like William Bourne advanced the field. Bourne's 1578 publication, A Treasure for Travellers, advocated for charts in long-distance voyages alongside soundings and compass corrections to enhance safety.[16] This transition, exemplified by the 1588 publication of The Mariners Mirrour—the first English printed sea atlas, translated from the Dutch Spieghel der Zeevaerdt by Anthony Ashley and engraved by Augustine Ryther—marked England's entry into systematic chartmaking, reducing reliance on imported Mediterranean and Dutch works.[16]Modern Hydrographic Charting

The institutionalization of modern hydrographic charting began in the late 18th and early 19th centuries with the establishment of dedicated national offices to produce standardized nautical charts for safe navigation and national defense. The United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO), founded in 1795 as the Hydrographic Department of the Admiralty, was tasked with surveying and charting global waters, issuing its first official chart in 1800 and playing a pivotal role in uniform cartographic standards through Admiralty charts that became a global benchmark.[17][18] Similarly, the United States Coast Survey, established in 1807 by President Thomas Jefferson under the Treasury Department, focused on systematic coastal mapping to support maritime commerce, evolving into a key producer of reliable charts that adhered to scientific precision.[19][20] These offices marked a shift from ad-hoc private charting to government-led efforts, ensuring consistency in scale, projection, and symbology across national and international waters. In the 19th century, technological innovations enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of hydrographic surveys underpinning chart production. Lead-line sounding, a traditional method refined during this period with marked lines and weighted leads to measure depths up to several hundred meters, remained the primary technique for seabed profiling until mechanical aids emerged.[5] Early steam-powered surveys, introduced in the mid-1800s, utilized steam winches to deploy and retrieve sounding lines more rapidly, allowing for broader coverage during expeditions and reducing human error in depth recordings.[21] These advancements, combined with improved sextant-based positioning, enabled the compilation of more detailed charts. The 20th century brought transformative shifts through acoustic and satellite technologies, revolutionizing seabed mapping for nautical charts. Echo sounding, invented around 1915–1919 using sonar principles to emit acoustic pulses and measure return echoes for depth, was first practically applied in hydrographic surveys in 1919 by French scientists, providing continuous profiles far superior to discrete lead-line measurements.[20][22] This was further advanced by multibeam echosounders, developed in the 1960s with the first operational system installed in 1963, which fan out multiple acoustic beams to map wide swaths of the seafloor simultaneously, achieving near-100% bottom coverage essential for high-resolution charts.[23][5] Post-World War II, satellite positioning systems integrated into surveys during the 1980s, particularly GPS from 1986 onward, delivered sub-meter horizontal accuracy, dramatically improving positional reliability in chart data and enabling real-time corrections during fieldwork.[24] Global coordination was formalized with the creation of the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) in 1921 as the International Hydrographic Bureau, which united national offices to standardize charting practices, symbols, and data exchange, fostering uniformity in over 3,000 international nautical charts.[25][26] This international framework gained legal impetus from the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which mandates coastal states to depict baselines, territorial seas up to 12 nautical miles, and exclusive economic zones up to 200 nautical miles on publicly available charts or lists of coordinates, deposited with the UN Secretary-General to ensure transparency and dispute resolution.[27] In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, hydrographic surveying advanced with the full operational capability of the Global Positioning System (GPS) in 1995, enabling decimeter-level precision in positioning. The 1990s saw the introduction of electronic navigational charts (ENCs) under IHO standards like S-57, facilitating digital integration. As of 2025, technologies such as satellite-derived bathymetry for remote areas, airborne LIDAR for shallow coastal waters, and autonomous vehicles—including uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs)—have transformed surveys, providing high-resolution data with enhanced efficiency and safety, as demonstrated in NOAA's ongoing hydrographic programs.[28][29]Data Sources and Acquisition

Hydrographic Surveys

Hydrographic surveys form the foundational process for acquiring precise underwater and coastal data essential for nautical chart production, focusing on measuring depths, mapping seabed features, and establishing vertical datums to ensure safe navigation. These surveys employ acoustic and optical technologies deployed from vessels, buoys, or aircraft to collect bathymetric and topographic information, which is then corrected for environmental variables such as tides and sound propagation conditions.[30] The primary goal is to detect hazards like wrecks or shoals and delineate fairways with sufficient accuracy to support chart compilation.[31] Core techniques for depth measurement rely on echosounders, which emit acoustic pulses and record the time for echoes to return from the seabed. Single-beam echosounders (SBES) provide targeted depth soundings along survey tracks, suitable for shallow or hazardous areas, while multibeam echosounders (MBES) generate fan-shaped swaths for comprehensive seafloor coverage, enabling 100% ensonification in critical zones.[32] The fundamental depth calculation uses the equation , where is depth, is the sound velocity in water, and is the round-trip travel time of the acoustic signal.[32] Sound velocity , typically around 1500 m/s in seawater, must be corrected for variations due to temperature (affecting velocity by about 4.5 m/s per °C), salinity (1.3 m/s per ‰), and pressure (1.6 m/s per 10 atm), often using empirical formulas like Coppens' equation or real-time profiles from conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) sensors to achieve sub-meter accuracy.[32] MBES systems integrate these corrections with vessel motion data for high-resolution bathymetry, detecting features as small as 1 m in shallow waters.[30] To image seabed features and analyze subsurface structures, surveys incorporate side-scan sonar and sub-bottom profilers. Side-scan sonar transmits acoustic pulses sideways from the survey vessel, creating shadow-derived images of the seafloor to identify wrecks, boulders, or texture variations that could pose navigation risks, with resolutions down to 1 m for object detection up to 20 m depth.[30] Sub-bottom profilers use lower-frequency waves (e.g., 3-16 kHz) to penetrate sediments, mapping layers and geological interfaces up to tens of meters below the seabed, which aids in understanding stability for port development or cable routing.[30] These tools complement echosounders by providing qualitative data on seabed composition, ensuring charts depict not just depths but also potential hazards.[30] Coastal surveys address nearshore and intertidal zones using specialized instruments for vertical control and shoreline delineation. Tide gauges, such as acoustic or pressure sensors, record water levels at 6-minute intervals to establish tidal datums like Mean Lower Low Water (MLLW), enabling depth reductions with uncertainties as low as 0.02 m.[30] GPS-equipped buoys provide real-time ellipsoidal-referenced tidal observations in offshore or dynamic areas, using differential GNSS for positioning accuracy within centimeters.[30] For shoreline mapping, airborne LIDAR systems emit green-wavelength lasers to penetrate shallow waters (up to 3-5 m), generating 3D models of topography and bathymetry with 0.5 m vertical accuracy and 4 m spot spacing, ideal for updating charted coastlines and detecting erosion.[30] International standards govern survey quality, with the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) S-44 specifying accuracy classes based on navigation risk. For Special Order surveys in harbors and critical channels, total vertical uncertainty (TVU) is limited by , where is depth in meters, m, and , yielding approximately 0.75% of depth for deeper waters (e.g., 0.5 m at 50 m depth) alongside 100% bathymetric coverage and 1 m feature detection.[31] These criteria ensure data supports safe under-keel clearance, with national bodies like NOAA adapting them for U.S. waters.[31] Conducting surveys in remote areas, such as polar regions, presents unique challenges including ice cover that blocks GPS signals and acoustic propagation, extreme cold reducing equipment efficiency, and logistical difficulties in deployment under dynamic ice shelves.[33] In the 2020s, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) have addressed these by enabling under-ice missions; for instance, the nupiri muka AUV mapped 60 km beneath the Thwaites Glacier in 2020, collecting bathymetric data with multibeam sonar despite communication constraints.[33] Similarly, Ran AUV deployments at Thwaites Glacier (2019-2022) covered tens of kilometers for seafloor topography, integrating acoustic navigation to overcome magnetic interference at high latitudes; the Ran was lost during a 2024 mission and replaced by Ran II in 2025.[33][34] An exemplary program is NOAA's Integrated Ocean and Coastal Mapping (IOCM), which coordinates hydrographic surveys across U.S. waters to acquire, integrate, and share bathymetric data from echosounders, LIDAR, and other sources, promoting efficient "map once, use many times" for navigation, habitat assessment, and infrastructure planning.[35] Established under the 2009 Ocean and Coastal Mapping Integration Act, IOCM ensures standardized data collection in coastal and offshore zones, enhancing nautical chart reliability through interagency collaboration.[35]Supplementary Data Sources

Supplementary data sources augment the primary hydrographic surveys that form the foundation of nautical charts by providing indirect, broad-scale information on underwater and coastal features. These inputs, derived from remote sensing and collaborative efforts, help fill gaps in coverage, particularly in remote or inaccessible areas, enabling more comprehensive nautical charting. Satellite altimetry missions, such as the Jason-3 launched in 2016, measure sea surface heights to derive gravity anomalies, which are used in bathymetric models to predict uncharted ocean depths. These models correlate gravitational variations caused by seafloor topography with satellite-observed deflections in sea level, offering global estimates where direct surveys are limited. For instance, multi-satellite altimetry data have produced gravity anomaly maps that support bathymetry predictions with resolutions approaching 1 km in deep waters.[36][37] Aerial photography and LiDAR surveys contribute detailed data on above-water features, such as cliffs, ports, and shorelines, which are essential for depicting coastal topography on nautical charts. Aerial imagery from sources like NOAA's programs captures high-resolution visuals to update shoreline positions and monitor changes, while LiDAR provides precise elevation data for topographic mapping. These technologies enable the identification of landmarks and infrastructure that aid navigation, with LiDAR achieving vertical accuracies of 15 cm or better in coastal zones.[38][39][40] Crowdsourced data from vessels enhances chart updates through real-time contributions, including Automatic Identification System (AIS) reports on positions and routes, and platforms like OpenSeaMap, which compile user-submitted nautical information into free, collaborative charts. AIS data tracks ship movements to identify navigable paths and potential hazards, while OpenSeaMap integrates volunteer inputs on seamarks, harbors, and depths for dynamic overlays. This approach allows rapid incorporation of observations from global maritime traffic, supplementing official surveys with timely, widespread coverage.[41][42] Environmental data sources, such as observations from weather buoys and records of oil spills, are integrated to depict currents, tides, and hazards on nautical charts. NOAA's National Data Buoy Center provides real-time measurements of ocean currents and meteorological conditions from moored buoys, informing dynamic navigational warnings. Oil spill records from NOAA's response programs track contamination risks, helping chart restricted areas and environmental threats. These inputs ensure charts reflect variable marine conditions beyond static bathymetry.[43][44][45] Despite their value, supplementary sources have limitations, including lower resolution and accuracy compared to direct hydrographic methods; for example, satellite-derived depths in the deep ocean typically achieve vertical accuracies of ±50-200 m due to signal noise and model assumptions. Crowdsourced data may also vary in quality, requiring validation to avoid errors in critical navigation areas. Recent developments in crowdsourced bathymetry processing support data validation and integration for mapping remote seafloors. The IHO's Data Centre for Digital Bathymetry reached over 1 billion total data points in 2024, including crowdsourced bathymetry, supporting faster updates to global nautical charts.[46][47]Production and Publication

Chart Compilation and Design

The compilation of nautical charts begins with the integration of raw hydrographic survey data, which serves as the foundational input for creating accurate navigational representations. This process involves transforming disparate datasets into a unified, reliable product suitable for maritime use. Hydrographic offices, such as those under the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), oversee this assembly to ensure safety and precision in depicting seafloors, coastlines, and hazards.[3] Data processing workflows start with cleaning survey data to remove outliers, correct instrumental errors, and standardize formats from sources like multibeam echosounders or lidar. Conflicts arising from overlapping surveys or positional discrepancies are resolved through methods such as least-squares adjustment, which minimizes errors in position fixes by optimizing redundant observations into a best-fit solution. This adjustment technique is particularly vital in hydrographic positioning, where multiple fixes enhance accuracy beyond individual measurements.[48][49] Design elements are selected based on the chart's intended purpose, with scale chosen to balance detail and coverage—for instance, 1:10,000 scales for intricate harbor areas requiring precise maneuvering information, contrasting with 1:1,500,000 scales for broad ocean passages emphasizing regional overviews. Sheet layouts are organized into folio series, where adjacent charts overlap at edges to facilitate seamless navigation across regions, ensuring consistent projection and datum usage.[7][50] Digital compilation relies on specialized software tools, including CARIS for bathymetric processing, symbol placement, and automated chart generation, and Hypack for survey data editing and export to chart-ready formats. These tools enable efficient handling of large datasets, supporting vector-based editing and real-time previews.[51][52] A significant historical shift occurred in the 1990s, transitioning from manual drafting on scribing tables—which involved hand-drawn lines and photographic reproduction—to computer-aided design (CAD) systems that digitized linework and automated layering. This evolution improved efficiency and reduced errors, aligning with the rise of electronic data management in hydrographic offices.[53] Verification stages encompass internal quality checks, such as cross-validation of depths and positions against source data, followed by peer reviews within hydrographic offices to confirm positional accuracy and feature completeness. These steps adhere to IHO guidelines, ensuring the final product meets navigational reliability standards before further production. Throughout design, compliance with IHO INT 1 standards is mandatory, dictating the use of standardized symbols, abbreviations, and colors for elements like buoys, wrecks, and contours to promote international uniformity and mariner familiarity.[54][55]Standards and International Publication

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) establishes global standards for nautical charts to ensure safety, consistency, and interoperability. The IHO's S-4 publication, "Regulations for International (INT) Charts and Chart Specifications of the IHO," provides detailed guidelines on chart design, content, scale, projections, and symbology for paper and raster charts, with the latest edition (4.9.0) issued in March 2021.[56] Complementing this, the IHO S-57 standard, "Transfer Standard for Digital Hydrographic Data" (Edition 3.1.0), defines the data structure and exchange format for Electronic Navigational Charts (ENCs), enabling compatibility with Electronic Chart Display and Information Systems (ECDIS) as required by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). While S-57 remains in force, the IHO is transitioning to the S-100 framework, with S-101 as the new ENC product specification; initial operational editions were adopted in 2025, supporting enhanced data for ECDIS from 2026 onward.[57] These standards are adopted by member states to facilitate international navigation, with S-4 addressing ambiguities in presentation to harmonize charts across borders.[3] National hydrographic offices publish nautical charts in accordance with IHO standards, tailoring them to regional needs while contributing to global coverage. In the United States, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) produces official charts for U.S. waters, including thousands of ENCs (with ongoing expansion toward approximately 9,000 cells) available for free download via its online portal since the late 1990s, with distribution also handled through certified print-on-demand agents for paper versions until the full discontinuation of traditional paper charts in early 2025.[8][58] The United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) publishes ADMIRALTY Standard Nautical Charts with worldwide coverage, emphasizing commercial shipping routes and ports, distributed digitally through e-services and via global agents.[59] Chart numbering systems vary by nation but follow logical schemes; for example, NOAA organizes U.S. charts into folios by region, with Folio 140 covering the Chesapeake Bay and Intracoastal Waterway, using sequential numbers like 12261 for specific approaches. Updates to charts are disseminated through Notices to Mariners (NtM), which correct discrepancies and incorporate new surveys. In the U.S., weekly NtM editions have been published by NOAA since 1887, compiling hydrographic changes, navigational warnings, and regulatory updates essential for maintaining chart accuracy.[60] Digitally, the IHO encourages free public access to ENCs to promote safety and data sharing, a trend accelerated by member states like NOAA providing unrestricted downloads, aligning with IMO carriage requirements for ECDIS.[61] Challenges in international publication include harmonizing symbols and data formats across diverse national systems, addressed through ongoing IHO revisions to S-4 and S-57. In 2025, the IHO is updating standards to account for climate-impacted coastlines, such as shifting shorelines and new polar routes, enhancing chart resilience to environmental changes while ensuring global interoperability.[62][63]Types of Nautical Charts

Paper Charts

Paper nautical charts represent the longstanding physical medium for maritime navigation, offering a tangible depiction of hydrographic data, coastlines, depths, and hazards essential for safe passage. Produced by national hydrographic offices such as NOAA and distributed through print-on-demand (POD) services, these charts are compiled from surveyed data and printed to international standards set by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). They serve as the primary or backup tool for plotting routes, identifying dangers, and conducting traditional celestial or dead reckoning navigation, particularly on vessels without advanced electronic systems.[64][3] These charts are printed on water-resistant paper or durable synthetic sheets to endure exposure to moisture and wear in marine environments, with modern POD processes employing inkjet plotters for precise color reproduction and clarity. Nautical paper charts vary by scale to suit different navigational needs: large-scale harbor charts (typically 1:2,000 to 1:20,000) provide intricate details for maneuvering in ports and confined waters; medium-scale coastal charts (1:20,000 to 1:150,000) cover nearshore areas with sufficient resolution for approach and inshore transit; and small-scale general charts (1:150,000 or smaller) offer broad overviews for open-sea planning and route selection. To accommodate their size, larger charts often incorporate folding mechanisms, allowing compact storage in chart tables or folios aboard ships.[65][66] In use, navigators manually plot positions, courses, and fixes on paper charts using specialized tools, such as dividers to measure distances between points and parallel rulers to align bearings with the chart's compass rose for accurate course setting. Updates to maintain currency are applied via Notices to Mariners, where minor alterations are penciled in by hand and significant changes—such as new wrecks or buoy relocations—are implemented through printed block corrections pasted over affected areas or by acquiring entirely new editions from the hydrographic authority. This manual correction process ensures compliance with safety regulations but requires diligent record-keeping of applied notices.[67][68][69] Paper charts offer key advantages, including independence from electrical power—critical during blackouts or equipment failures—and a tactile format that facilitates intuitive training and rapid visual scanning for situational awareness. However, they present disadvantages such as physical bulk, which complicates storage on smaller vessels, and inherent delays in correction dissemination compared to instantaneous digital updates. Despite a global shift toward electronic formats, paper charts retain mandatory status as a backup under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS, 1974, as amended), particularly for ships relying on Electronic Chart Display and Information Systems (ECDIS) to meet carriage requirements. An illustrative hybrid example is the Raster Nautical Chart (RNC), a geo-referenced digital scan of traditional paper charts that preserves their symbology and detail for overlay in electronic navigation software while bridging to fully digital workflows.[70][71][72][73]Electronic Navigational Charts

Electronic Navigational Charts (ENCs) represent the digital evolution of nautical charts, providing vector-based datasets that enable interactive and layered visualization of maritime information. Developed under International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) standards, ENCs adhere to the S-57 format, the primary transfer standard for digital hydrographic data since 2000 and still in widespread use as of 2025, with its planned successor S-101—part of the S-100 Universal Hydrographic Data Model—having operational editions approved in 2024 and initial ECDIS support starting in 2026. The transition to S-101 includes a phase-in period, with S-100-compatible ECDIS becoming legally permissible from 1 January 2026 and mandatory for new installations by 1 January 2029, allowing backward compatibility with S-57 during the interim. These formats structure data into discrete layers, allowing separate rendering of elements such as bathymetry for depths, aids to navigation, and obstructions or hazards, which facilitates scalable zooming and selective display without loss of detail.[3][74][75][76][77] ENCs are primarily utilized through Electronic Chart Display and Information Systems (ECDIS), which are approved by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) for paperless navigation under the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention, specifically regulation V/19 as amended in 2009. This mandate requires ECDIS on new passenger ships of 500 gross tonnage and above, and cargo ships of 3,000 gross tonnage and above engaged on international voyages, with phased implementation for existing vessels starting in 2012. ECDIS hardware must be type-approved to meet IMO performance standards, ensuring compatibility with official ENCs and integration of real-time positioning from GPS or other sources to provide automated route monitoring and safety alerts.[78] Updates to ENCs are distributed weekly by hydrographic offices (HOs) or Regional ENC Coordinating Centres (RENCs) via encrypted files, enabling remote delivery through internet downloads, DVDs, or satellite links to maintain currency with navigational changes. These updates integrate with Automatic Radar Plotting Aids (ARPA) systems, allowing radar video overlays on ECDIS displays for enhanced situational awareness, such as superimposing real-time radar echoes on charted features to verify positions or detect uncharted hazards. For example, integration with the Automatic Identification System (AIS) enables dynamic display of nearby vessel positions as overlaid targets, supporting collision avoidance by highlighting potential hazards in real time.[79][80][81] The advantages of ENCs include scalability for varying display resolutions, support for dynamic overlays such as weather data or tidal predictions, and automation features like machine-readable catalogues that streamline route planning without manual hardware upgrades. However, challenges such as cybersecurity risks— including vulnerabilities in data transfer via removable media or networks—are addressed through IHO guidelines and enhancements in the S-100 framework, which incorporate improved encryption and risk management protocols for ECDIS and ENC handling. By 2025, ENCs achieve extensive global coverage for international shipping routes through coordinated IHO efforts, with free distribution provided by many HOs in regions like the United States via NOAA and Europe through PRIMAR RENC. Paper charts serve as essential backups for ECDIS in case of system failure, as required by SOLAS.[82][83][61]Chart Content and Symbology

Symbols, Labels, and Abbreviations

Nautical charts employ a standardized visual language defined by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) in Chart INT 1, which specifies symbols, abbreviations, and terms for paper charts to ensure uniformity across international publications.[3] This system, detailed in Edition 8 (2020), categorizes symbols into sections such as topography, hydrography, aids to navigation, and hazards, allowing mariners to interpret chart features rapidly without textual explanation.[3] The U.S. Chart No. 1, which incorporates IHO INT 1 standards, provides a reference for these elements on nautical charts produced by NOAA and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. In topography, symbols depict land features using hachures—short lines radiating from hill summits, with thickness indicating slope steepness—to represent elevation and relief. Hydrographic symbols illustrate underwater vegetation, such as kelp or seaweed, with wavy lines or irregular curves extending from the shore or seabed to denote areas that may foul anchors or propellers. Common aids to navigation include buoys, where a green conical shape signifies a starboard-hand mark in IALA Region A (red left returning from seaward), guiding vessels to keep it on the left when proceeding from seaward.[84] Wrecks are marked by a dotted cross or plus sign enclosed in a circle, with dots indicating dangerous or foul ground around the site. Lights are portrayed using magenta arcs to show sector coverage, emanating from a black dot representing the light's position, with the arc's color and length denoting visibility and direction.[85] Labels on nautical charts use upright roman typeface for place names, ensuring clarity and distinction from italicized features like rocks or obstructions.[86] Depth labels appear as numerals adjacent to sounding positions, typically in meters or feet as specified in the chart title, with units omitted if consistent throughout but underlined for emphasis on critical shallows. Abbreviations streamline notation; for instance, "Obstr" denotes an obstruction of unknown depth, while "CD" refers to chart datum, the reference level for all soundings, often mean lower low water in tidal areas.[87] Color conventions enhance readability: water areas are white for deep soundings, with a blue tint overlaying shallow zones to highlight potential grounding risks; land is depicted in yellowish buff; and magenta outlines or fills mark man-made hazards, lights, and structures for high visibility.[50] Recent updates address emerging features, with 2024 IHO proposals for S-101 electronic charts introducing specific symbols for renewable energy installations, such as a dedicated icon for offshore production areas categorized as wind farms (turbines shown as vertical lines with blades) or wave farms; these proposals were incorporated into the S-101 standard approved in December 2024, with first S-101 ENCs entering production in 2025, building on S-4 regulations to depict safe passage around these obstructions.[88][57]| Category | Example Symbol Description | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Topography | Hachures (lines from summit) | Hill or elevation contour |

| Hydrography | Wavy lines with fronds | Kelp or seaweed bed |

| Aids to Navigation | Green triangle (cone) | Starboard-hand buoy |

| Hazards | Dotted + in circle | Dangerous wreck |

| Lights | Magenta sector arc | Light visibility sector |

| Abbreviations | Obstr, CD | Obstruction; Chart Datum |