Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pulmonary alveolus

View on Wikipedia

| Pulmonary alveolus | |

|---|---|

The alveoli | |

| Details | |

| System | Respiratory system |

| Location | Lung |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | alveolus pulmonis |

| MeSH | D011650 |

| TH | H3.05.02.0.00026 |

| FMA | 7318 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A pulmonary alveolus (pl. alveoli; from Latin alveolus 'little cavity'), also called an air sac or air space, is one of millions of hollow, distensible cup-shaped cavities in the lungs where pulmonary gas exchange takes place.[1] Oxygen is exchanged for carbon dioxide at the blood–air barrier between the alveolar air and the pulmonary capillary.[2] Alveoli make up the functional tissue of the mammalian lungs known as the lung parenchyma, which takes up 90 percent of the total lung volume.[3][4]

Alveoli are first located in the respiratory bronchioles that mark the beginning of the respiratory zone. They are located sparsely in these bronchioles, line the walls of the alveolar ducts, and are more numerous in the blind-ended alveolar sacs.[5] The acini are the basic units of respiration, with gas exchange taking place in all the alveoli present.[6] The alveolar membrane is the gas exchange surface, surrounded by a network of capillaries. Oxygen is diffused across the membrane into the capillaries and carbon dioxide is released from the capillaries into the alveoli to be breathed out.[7][8]

Alveoli are particular to mammalian lungs. Different structures are involved in gas exchange in other vertebrates.[9]

Structure

[edit]

The alveoli are first located in the respiratory bronchioles as scattered outpockets, extending from their lumens. The respiratory bronchioles run for considerable lengths and become increasingly alveolated with side branches of alveolar ducts that become deeply lined with alveoli. The ducts number between two and eleven from each bronchiole.[10] Each duct opens into five or six alveolar sacs into which clusters of alveoli open.

Each terminal respiratory unit is called an acinus and consists of the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs, and alveoli. New alveoli continue to form until the age of eight years.[5]

A typical pair of human lungs contains about 480 million alveoli,[11] providing a total surface area for gas exchange of between 70 and 80 square metres.[10] Each alveolus is wrapped in a fine mesh of capillaries covering about 70% of its area.[12] The diameter of an alveolus is between 200 and 500 μm.[12]

Microanatomy

[edit]An alveolus consists of an epithelial layer of simple squamous epithelium (very thin, flattened cells),[13] and an extracellular matrix surrounded by capillaries. The epithelial lining is part of the alveolar membrane, also known as the respiratory membrane, that allows the exchange of gases. The membrane has several layers – a layer of alveolar lining fluid that contains surfactant, the epithelial layer and its basement membrane; a thin interstitial space between the epithelial lining and the capillary membrane; a capillary basement membrane that often fuses with the alveolar basement membrane, and the capillary endothelial membrane. The whole membrane however is only between 0.2 μm at its thinnest part and 0.6 μm at its thickest.[14]

In the alveolar walls there are interconnecting air passages between the alveoli known as the pores of Kohn. The alveolar septum that separates the alveoli in the alveolar sac contains some collagen fibers and elastic fibers. The septa also house the enmeshed capillary network that surrounds each alveolus.[3] The elastic fibres allow the alveoli to stretch when they fill with air during inhalation. They then spring back during exhalation in order to expel the carbon dioxide-rich air.

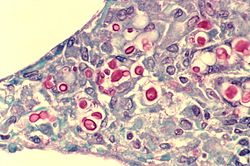

There are three major types of alveolar cell. Two types are pneumocytes or pneumonocytes known as type I and type II cells found in the alveolar wall, and a large phagocytic cell known as an alveolar macrophage that moves about in the lumens of the alveoli, and in the connective tissue between them. Type I cells, also called type I pneumocytes, or type I alveolar cells, are squamous, thin and flat and form the structure of the alveoli. Type II cells, also called type II pneumocytes or type II alveolar cells, release pulmonary surfactant to lower surface tension, and can also differentiate to replace damaged type I cells.[12][15]

Development

[edit]Development of the earliest structures that will contain alveoli begins on day 22 and is divided into five stages: embryonic, pseudoglandular, canalicular, saccular, and alveolar stage.[16] The alveolar stage begins approximately 36 weeks into development. Immature alveoli appear as bulges from the sacculi which invade the primary septa. As the sacculi develop, the protrusions in the primary septa become larger; new septations are longer and thinner and are known as secondary septa.[16] Secondary septa are responsible for the final division of the sacculi into alveoli. Majority of alveolar division occurs within the first 6 months but continue to develop until 3 years of age. To create a thinner diffusion barrier, the double-layer capillary network fuse into one network, each one closely associated with two alveoli as they develop.[16]

In the first three years of life, the enlargement of lungs is a consequence of the increasing number of alveoli; after this point, both the number and size of alveoli increases until the development of lungs finishes at approximately 8 years of age.[16]

Function

[edit]

Type I cells

[edit]

Type I cells are the larger of the two cell types; they are thin, flat epithelial lining cells (membranous pneumocytes), that form the structure of the alveoli.[3] They are squamous (giving more surface area to each cell) and have long cytoplasmic extensions that cover more than 95% of the alveolar surface.[12][17]

Type I cells are involved in the process of gas exchange between the alveoli and blood. These cells are extremely thin – sometimes only 25 nm – the electron microscope was needed to prove that all alveoli are lined with epithelium. This thin lining enables a fast diffusion of gas exchange between the air in the alveoli and the blood in the surrounding capillaries.

The nucleus of a type I cell occupies a large area of free cytoplasm and its organelles are clustered around it reducing the thickness of the cell. This also keeps the thickness of the blood-air barrier reduced to a minimum.

The cytoplasm in the thin portion contains pinocytotic vesicles which may play a role in the removal of small particulate contaminants from the outer surface. In addition to desmosomes, all type I alveolar cells have occluding junctions that prevent the leakage of tissue fluid into the alveolar air space.

The relatively low solubility (and hence rate of diffusion) of oxygen necessitates the large internal surface area (about 80 square m [96 square yards]) and very thin walls of the alveoli. Weaving between the capillaries and helping to support them is an extracellular matrix, a meshlike fabric of elastic and collagenous fibres. The collagen fibres, being more rigid, give the wall firmness, while the elastic fibres permit expansion and contraction of the walls during breathing.

Type I pneumocytes are unable to replicate and are susceptible to toxic insults. In the event of damage, type II cells can proliferate and differentiate into type I cells to compensate.[18]

Type II cells

[edit]Type II cells are cuboidal and much smaller than type I cells.[3] They are the most numerous cells in the alveoli, yet do not cover as much surface area as the squamous type I cells.[18] Type II cells (granulous pneumocytes) in the alveolar wall contain secretory organelles known as lamellar bodies or lamellar granules, that fuse with the cell membranes and secrete pulmonary surfactant. This surfactant is a film of fatty substances, a group of phospholipids that reduce alveolar surface tension. The phospholipids are stored in the lamellar bodies. Without this coating, the alveoli would collapse. The surfactant is continuously released by exocytosis. Reinflation of the alveoli following exhalation is made easier by the surfactant, which reduces surface tension in the thin fluid lining of the alveoli. The fluid coating is produced by the body in order to facilitate the transfer of gases between blood and alveolar air, and the type II cells are typically found at the blood–air barrier.[19][20]

Type II cells start to develop at about 26 weeks of gestation, secreting small amounts of surfactant. However, adequate amounts of surfactant are not secreted until about 35 weeks of gestation – this is the main reason for increased rates of infant respiratory distress syndrome, which drastically reduces at ages above 35 weeks gestation.

Type II cells are also capable of cellular division, giving rise to more type I and II alveolar cells when the lung tissue is damaged.[21]

MUC1, a human gene associated with type II pneumocytes, has been identified as a marker in lung cancer.[22]

The importance of the type 2 lung alveolar cells in the development of severe respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 and potential mechanisms on how these cells are protected by the SSRIs fluvoxamine and fluoxetine was summarized in a review in April 2022.[23]

Alveolar macrophages

[edit]The alveolar macrophages reside on the internal luminal surfaces of the alveoli, the alveolar ducts, and the bronchioles. They are mobile scavengers that serve to engulf foreign particles in the lungs, such as dust, bacteria, carbon particles, and blood cells from injuries.[24] They are also called pulmonary macrophages, and dust cells. Alveolar macrophages also play a crucial role in immune responses against viral pathogens in the lungs.[25] They secrete cytokines and chemokines, which recruit and activate other immune cells, initiate type I interferon signaling, and inhibit the nuclear export of viral genomes.[25]

Clinical significance

[edit]Diseases

[edit]Surfactant

[edit]Insufficient surfactant in the alveoli is one of the causes that can contribute to atelectasis (collapse of part or all of the lung). Without pulmonary surfactant, atelectasis is a certainty.[26] The severe condition of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is caused by a deficiency or dysfunction of surfactant.[27] Insufficient surfactant in the lungs of preterm infants causes infant respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS). The lecithin–sphingomyelin ratio is a measure of fetal amniotic fluid to indicate lung maturity or immaturity.[28] A low ratio indicates a risk factor for IRDS. Lecithin and sphingomyelin are two of the glycolipids of pulmonary surfactant.

Impaired surfactant regulation can cause an accumulation of surfactant proteins to build up in the alveoli in a condition called pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. This results in impaired gas exchange.[29]

Inflammation

[edit]Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung tissue, which can be caused by both viruses and bacteria. Cytokines and fluids are released into the alveolar cavity, interstitium, or both, in response to infection, causing the effective surface area of gas exchange to be reduced. In severe cases where cellular respiration cannot be maintained, supplemental oxygen may be required.[30][31]

- Diffuse alveolar damage can be a cause of acute respiratory distress syndrome(ARDS) a severe inflammatory disease of the lung.[32]: 187

- In asthma, the bronchioles become narrowed, causing the amount of air flow into the lung tissue to be greatly reduced. It can be triggered by irritants in the air, photochemical smog for example, as well as substances to which a person is allergic.

- Chronic bronchitis occurs when an abundance of mucus is produced by the lungs. The production of mucus occurs naturally when the lung tissue is exposed to irritants. In chronic bronchitis, the air passages into the alveoli, the respiratory bronchioles, become clogged with mucus. This causes increased coughing in order to remove the mucus, and is often a result of extended periods of exposure to cigarette smoke.

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Structural

[edit]

Almost any type of lung tumor or lung cancer can compress the alveoli and reduce gas exchange capacity. In some cases the tumor will fill the alveoli.[33]

- Cavitary pneumonia is a process in which the alveoli are destroyed and produce a cavity. As the alveoli are destroyed, the surface area for gas exchange to occur becomes reduced. Further changes in blood flow can lead to decline in lung function.

- Emphysema is another disease of the lungs, whereby the elastin in the walls of the alveoli is broken down by an imbalance between the production of neutrophil elastase (elevated by cigarette smoke) and alpha-1 antitrypsin (the activity varies due to genetics or reaction of a critical methionine residue with toxins including cigarette smoke). The resulting loss of elasticity in the lungs leads to prolonged times for exhalation, which occurs through passive recoil of the expanded lung. This leads to a smaller volume of gas exchanged per breath.

- Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis is a rare lung disorder of small stone formation in the alveoli.

- Several factors, including smoking, viral infections, and aging, contribute to physical damage to type II alveolar cells. Some studies have linked injury to these cells to the proliferation of fibrosis in the lungs and the onset of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.[34]

Fluid

[edit]A pulmonary contusion is a bruise of the lung tissue caused by trauma.[35] Damaged capillaries from a contusion can cause blood and other fluids to accumulate in the tissue of the lung, impairing gas exchange.

Pulmonary edema is the buildup of fluid in the parenchyma and alveoli. An edema is usually caused by left ventricular heart failure, or by damage to the lung or its vasculature.

Coronavirus

[edit]Because of the high expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in type II alveolar cells, the lungs are susceptible to infections by some coronaviruses including the viruses that cause severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)[36] and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).[37]

Additional images

[edit]-

Blood circulation around alveoli

-

Diagrammatic view of lung showing magnified inner structures including alveolar sacs at 10) and lobules at 9)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Pulmonary Gas Exchange - MeSH". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. NCBI. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Alveoli". cancer.gov. National Cancer Institute. 2 February 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Knudsen, L; Ochs, M (December 2018). "The micromechanics of lung alveoli: structure and function of surfactant and tissue components". Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 150 (6): 661–676. doi:10.1007/s00418-018-1747-9. PMC 6267411. PMID 30390118.

- ^ Jones, Jeremy. "Lung parenchyma | Radiology Reference Article". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ a b Moore K (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy. Wolters Kluwer. p. 336. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ Hansen JE, Ampaya EP, Bryant GH, Navin JJ (June 1975). "Branching pattern of airways and air spaces of a single human terminal bronchiole". Journal of Applied Physiology. 38 (6): 983–9. doi:10.1152/jappl.1975.38.6.983. PMID 1141138.

- ^ Hogan CM (2011). "Respiration". In McGinley M, Cleveland CJ (eds.). Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, D.C.: National council for Science and the Environment.

- ^ Paxton S, Peckham M, Knibbs A (2003). "Functions of the Respiratory Portion". The Leeds Histology Guide. Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Leeds.

- ^ Daniels CB, Orgeig S (August 2003). "Pulmonary surfactant: the key to the evolution of air breathing". News in Physiological Sciences. 18 (4): 151–7. doi:10.1152/nips.01438.2003. PMID 12869615.

- ^ a b Spencer's pathology of the lung (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 1996. pp. 22–25. ISBN 0-07-105448-0.

- ^ Ochs M (2004). "The number of alveoli in the human lung". Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1 (169): 120–4. doi:10.1164/rccm.200308-1107OC. PMID 14512270.

- ^ a b c d Stanton, Bruce M.; Koeppen, Bruce A., eds. (2008). Berne & Levy physiology (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier. pp. 418–422. ISBN 978-0-323-04582-7.

- ^ "Bronchi, Bronchial Tree & Lungs". SEER Training Modules. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute.

- ^ Hall J (2011). Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. Saunders Elsevier. pp. 489–491. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ^ Naeem, Ahmed; Rai, Sachchida N.; Pierre, Louisdon (2021). "Histology, Alveolar Macrophages". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30020685. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Rehman S, Bacha D (8 August 2022). Embryology, Pulmonary. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31335092.

- ^ Weinberger S, Cockrill B, Mandell J (2019). Principles of pulmonary medicine (Seventh ed.). Elsevier. pp. 126–129. ISBN 978-0-323-52371-4.

- ^ a b Gray, Henry; Standring, Susan; Anhand, Neel, eds. (2021). Gray's Anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (42nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 1035. ISBN 978-0-7020-7705-0.

- ^ Ross MH, Pawlina W (2011). Histology, A Text and Atlas (Sixth ed.).

- ^ Fehrenbach H (2001). "Alveolar epithelial type II cell: defender of the alveolus revisited". Respiratory Research. 2 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1186/rr36. PMC 59567. PMID 11686863.

- ^ "Lung – Regeneration – Nonneoplastic Lesion Atlas". National Toxicology Program. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ Jarrard JA, Linnoila RI, Lee H, Steinberg SM, Witschi H, Szabo E (December 1998). "MUC1 is a novel marker for the type II pneumocyte lineage during lung carcinogenesis". Cancer Research. 58 (23): 5582–9. PMID 9850098.

- ^ Mahdi, Mohamed; Hermán, Levente; Réthelyi, János M.; Bálint, Bálint László (January 2022). "Potential Role of the Antidepressants Fluoxetine and Fluvoxamine in the Treatment of COVID-19". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (7): 3812. doi:10.3390/ijms23073812. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8998734. PMID 35409171.

- ^ "The trachea and the stem bronchi". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ^ a b Malainou, Christina; Abdin, Shifaa M.; Lachmann, Nico; Matt, Ulrich; Herold, Susanne (2 October 2023). "Alveolar macrophages in tissue homeostasis, inflammation, and infection: evolving concepts of therapeutic targeting". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 133 (19). doi:10.1172/JCI170501. ISSN 1558-8238. PMC 10541196. PMID 37781922.

- ^ Saladin KS (2007). Anatomy and Physiology: the unity of form and function. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-322804-4.

- ^ Sever N, Miličić G, Bodnar NO, Wu X, Rapoport TA (January 2021). "Mechanism of Lamellar Body Formation by Lung Surfactant Protein B". Mol Cell. 81 (1): 49–66.e8. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2020.10.042. PMC 7797001. PMID 33242393.

- ^ St Clair C, Norwitz ER, Woensdregt K, Cackovic M, Shaw JA, Malkus H, Ehrenkranz RA, Illuzzi JL (September 2008). "The probability of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome as a function of gestational age and lecithin/sphingomyelin ratio". Am J Perinatol. 25 (8): 473–80. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1085066. PMC 3095020. PMID 18773379.

- ^ Kumar, A; Abdelmalak, B; Inoue, Y; Culver, DA (July 2018). "Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in adults: pathophysiology and clinical approach". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 6 (7): 554–565. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30043-2. PMID 29397349. S2CID 27932336.

- ^ "Pneumonia – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "Pneumonia Symptoms and Diagnosis". American Lung Association. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston S, Davidson S (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ^ Mooi W (1996). "Common Lung Cancers". In Hasleton P (ed.). Spencer's Pathology of the Lung. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 1076. ISBN 0-07-105448-0.

- ^ Parimon, Tanyalak; Yao, Changfu; Stripp, Barry R; Noble, Paul W; Chen, Peter (25 March 2020). "Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cells as Drivers of Lung Fibrosis in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (7): 2269. doi:10.3390/ijms21072269. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 7177323. PMID 32218238.

- ^ "Pulmonary Contusion – Injuries and Poisoning". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Kuba K, Imai Y, Ohto-Nakanishi T, Penninger JM (October 2010). "Trilogy of ACE2: a peptidase in the renin-angiotensin system, a SARS receptor, and a partner for amino acid transporters". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 128 (1): 119–28. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.06.003. PMC 7112678. PMID 20599443.

- ^ Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, Peng J, Dan H, Zeng X, et al. (February 2020). "High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa". International Journal of Oral Science. 12 (1): 8. doi:10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x. PMC 7039956. PMID 32094336.

External links

[edit]- Pulmonary+Alveoli at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Pulmonary alveolus

View on GrokipediaStructure

Location and organization

The pulmonary alveoli represent the terminal expansions of the respiratory tree, forming the primary site of gas exchange within the lung's respiratory zone. This zone begins at the respiratory bronchioles, where alveoli first appear sparsely along the walls, and extends through alveolar ducts—tubular structures lined almost entirely by alveoli—to alveolar sacs, which are polyhedral clusters of 20 to 30 alveoli sharing a common opening. In adult human lungs, these structures number approximately 480 million, distributed bilaterally across the two lungs.[2] The collective surface area provided by these alveoli totals 70 to 80 square meters in adults, a vast expanse that facilitates efficient gas exchange by maximizing contact between air and blood. Alveolar septa, the thin walls separating adjacent alveoli, house an extensive network of pulmonary capillaries in close apposition to the epithelial lining, optimizing diffusion pathways. Embedded within these septa are elastic fibers, primarily composed of elastin, which confer the lung's elastic recoil, enabling passive expiration and structural integrity during breathing cycles.[3][4] Alveolar density exhibits regional variations within the human lung, decreasing from the apex to the base in the upright position due to gravitational influences on thoracic stress and airspace expansion.[5] Across species, alveolar density and surface area scale with metabolic demands; for instance, smaller mammals or those adapted for high oxygen needs, such as bats, possess relatively higher densities to support elevated aerobic capacities compared to larger, less active species.[6]Microanatomy

The pulmonary alveolus features a delicate epithelial lining that forms the primary interface for gas exchange, consisting of flat squamous type I pneumocytes covering approximately 95% of the surface and cuboidal type II pneumocytes occupying the remaining 5%. This lining, with a total blood-gas barrier thickness ranging from 0.2 to 1.0 μm in regions of direct contact, overlies a fused basement membrane shared with the underlying capillary endothelium, minimizing the diffusion path while maintaining structural integrity.[3][7] Alveolar walls incorporate a network of elastic and collagen fibers that provide essential structural support and elasticity, allowing the alveoli to expand during inspiration and recoil during expiration. Elastic fibers, primarily composed of elastin, enable compliance and prevent collapse, while collagen fibers, including type III variants, offer tensile strength to resist overdistension and maintain wall stability.[3][8] Interconnecting adjacent alveoli are the pores of Kohn, small fenestrations measuring 10-15 μm in diameter that permit collateral airflow and pressure equalization between neighboring units. These pores, bordered by elastic and reticular fibers, enhance ventilation uniformity without compromising the primary barrier.[3] The interalveolar septa, which separate adjacent alveoli, contain sparse connective tissue elements including fibroblasts and pericytes to preserve a minimal diffusion distance. Fibroblasts contribute to matrix production and remodeling, while pericytes support capillary integrity within the septa, ensuring the overall thinness of the structure (typically under 1 μm in gas-exchange zones).[9]Development

Prenatal development

The prenatal development of the pulmonary alveoli begins with the formation of the lung bud from the ventral wall of the foregut endoderm at approximately day 22 post-fertilization, marking the onset of respiratory system organogenesis.[10] This initial outgrowth, known as the respiratory diverticulum, elongates and bifurcates into primary bronchial buds by the end of the fourth week, initiating the embryonic stage (weeks 3-6) where the basic tracheobronchial tree architecture is established.[10] Lung development progresses through five canonical stages: the pseudoglandular stage (weeks 5-17), characterized by extensive branching morphogenesis to form the conducting airways up to the terminal bronchioles; the canalicular stage (weeks 16-25), during which respiratory bronchioles and primitive alveolar ducts emerge with initial vascularization; the saccular stage (weeks 24-38), featuring expansion of terminal air sacs and thinning of the interstitium to prepare for gas exchange; and the alveolar stage, which begins around week 36 with the formation of mature alveoli through secondary septation.[10] Branching morphogenesis during these early stages is primarily driven by signaling pathways involving fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10), sonic hedgehog (SHH), and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), which regulate epithelial-mesenchymal interactions to generate the intricate airway tree.[10] Vascular development is tightly coupled with epithelial budding, particularly in the canalicular stage, where capillary networks proliferate and closely appose the epithelial lining to form the foundational blood-air barrier.[10] By approximately week 20, cuboidal epithelial cells differentiate into type I pneumocytes (thin, squamous cells for gas diffusion) and type II pneumocytes (which produce surfactant), with type II cells appearing first in the canalicular phase and giving rise to type I cells during the saccular stage.[10] Surfactant production by type II pneumocytes begins in the late saccular phase around week 32, stabilizing alveolar structures for postnatal respiration.[10] Genetic factors play a critical role in alveolar formation; for instance, mutations in the FOXF1 gene, a key regulator of mesenchymal development, are associated with alveolar hypoplasia and conditions like alveolar capillary dysplasia, leading to reduced capillary density and impaired septation.[11] Environmental influences, such as maternal smoking, can disrupt branching morphogenesis by altering nicotine exposure effects on fetal lung epithelial growth and vascular patterning, potentially resulting in fewer airway branches and smaller alveolar units.[12]Postnatal development

Postnatal development of the pulmonary alveoli involves a phase of rapid proliferation and maturation that continues well after birth, primarily through the process of alveolar septation, where secondary septa form within the saccules to create mature alveoli. At birth, the human lung contains approximately 50 million alveoli, which multiply exponentially during the first two years of life and continue to increase at a slower rate until around age 8, reaching about 480 million in adulthood.[13][14][15] This septation and multiplication expand the alveolar gas exchange surface, tripling in area during the first two years from roughly 3–5 m² at birth to about 10–15 m² by age 2, driven by the addition of new alveoli rather than enlargement of existing ones.[16][17] Environmental factors significantly influence this early growth; adequate nutrition supports optimal alveolar multiplication, while malnutrition can impair it, and postnatal infections or exposure to mechanical ventilation—particularly in preterm infants—pose risks of disrupted septation and reduced final alveolar number.[18][19] Hormonal signals, notably glucocorticoids, play a key role in regulating postnatal alveolar maturation by promoting septal formation and epithelial differentiation, though excessive postnatal exposure can alter fibroblast progenitors and potentially hinder long-term growth.[20] Additionally, epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation changes in response to hypoxia, influence gene expression in alveolar cells, adapting development to environmental oxygen levels but potentially leading to persistent alterations if hypoxia is prolonged.[21] At birth, type II pneumocytes rapidly adapt surfactant production to support the transition to air breathing.[22] With advancing age, the number of alveoli begins to decline after early adulthood, contributing to reduced lung elasticity and diminished gas exchange efficiency by age 50 and beyond, as alveolar walls thicken and the overall surface area decreases.[23][24] This age-related loss, estimated at 10–20% by late adulthood in some studies, exacerbates ventilatory limitations and increases susceptibility to respiratory challenges.[25]Function

Gas exchange mechanism

The gas exchange mechanism in pulmonary alveoli relies on passive diffusion of oxygen (O₂) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) across the thin alveolar-capillary membrane, driven by partial pressure gradients between alveolar air and pulmonary capillary blood. This process is quantitatively described by Fick's law of diffusion, which posits that the flux of gas (V) across the membrane is directly proportional to the available surface area (A), the diffusion coefficient of the gas (D), and the partial pressure difference (ΔP), while inversely proportional to the membrane thickness (T): /07:_Fundamentals_of_Gas_Exchange/7.02:_Fick's_law_of_diffusion)The extremely thin barrier provided by type I pneumocytes minimizes T, while the expansive alveolar surface area maximizes A, optimizing diffusion efficiency.[26] Notably, although the molecular size of O₂ is smaller than CO₂, the higher solubility of CO₂ results in a diffusion coefficient approximately 20 times greater, enabling comparable exchange rates despite a smaller ΔP for CO₂.[27] Under normal physiological conditions, alveolar partial pressure of O₂ (PAO₂) is approximately 100 mmHg, contrasting with 40 mmHg in mixed venous blood, which establishes a steep gradient for O₂ uptake. Alveolar PCO₂ remains around 40 mmHg, slightly below the 45-46 mmHg in venous blood, facilitating CO₂ elimination. These gradients are optimized by the ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) ratio, typically averaging 0.8 in healthy lungs, which balances alveolar ventilation (V) with capillary perfusion (Q) to prevent mismatches that could impair gas transfer.[28][29] In the bloodstream, O₂ primarily binds to hemoglobin within erythrocytes, vastly increasing transport capacity compared to plasma solubility alone. For CO₂, about 5-10% binds directly to hemoglobin's amino groups, forming carbaminohemoglobin, which aids its venous return to the lungs. The Bohr effect enhances overall efficiency by reducing hemoglobin's O₂ affinity in the presence of elevated CO₂ and H⁺ (low pH), promoting O₂ unloading in tissues and indirectly supporting CO₂ loading via reciprocal interactions. Henry's law governs gas solubility in plasma, stating that the concentration of dissolved gas is directly proportional to its partial pressure, which is essential for the initial dissolution of O₂ and CO₂ prior to hemoglobin binding or bicarbonate formation.[30][31][32] Several factors influence gas exchange efficiency through alterations in Fick's law parameters. At high altitudes, reduced barometric pressure lowers inspired PO₂ and thus alveolar PAO₂, diminishing the ΔP for O₂ and inducing hypoxia despite hyperventilation attempts to compensate. Conversely, during exercise, cardiac output rises proportionally with metabolic demand, increasing pulmonary perfusion (Q) and recruiting additional capillaries, which sustains V/Q matching and enhances overall gas transfer when ventilation rises accordingly.[28][33]