Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Capillary

View on Wikipedia

| Capillary | |

|---|---|

Diagram of a capillary | |

A simplified illustration of a capillary network | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | US: /ˈkæpəlɛri/, UK: /kəˈpɪləri/ |

| System | Circulatory system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vas capillare[1] |

| MeSH | D002196 |

| TA98 | A12.0.00.025 |

| TA2 | 3901 |

| TH | H3.09.02.0.02001 |

| FMA | 63194 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A capillary is a small blood vessel, from 5 to 10 micrometres in diameter, and is part of the microcirculation system. Capillaries are microvessels and the smallest blood vessels in the body. They are composed of only the tunica intima (the innermost layer of an artery or vein), consisting of a thin wall of simple squamous endothelial cells.[2] They are the site of the exchange of many substances from the surrounding interstitial fluid, and they convey blood from the smallest branches of the arteries (arterioles) to those of the veins (venules). Other substances which cross capillaries include water, oxygen, carbon dioxide, urea,[3] glucose, uric acid, lactic acid and creatinine. Lymph capillaries connect with larger lymph vessels to drain lymphatic fluid collected in microcirculation.

Etymology

[edit]Capillary comes from the Latin word capillaris, meaning "of or resembling hair", with use in English beginning in the mid-17th century.[4] The meaning stems from the tiny, hairlike diameter of a capillary.[4] While capillary is usually used as a noun, the word also is used as an adjective, as in "capillary action", in which a liquid flows without influence of external forces, such as gravity.

Structure

[edit]

Blood flows from the heart through arteries, which branch and narrow into arterioles, and then branch further into capillaries where nutrients and wastes are exchanged. The capillaries then join and widen to become venules, which in turn widen and converge to become veins, which then return blood back to the heart through the venae cavae. In the mesentery, metarterioles form an additional stage between arterioles and capillaries.

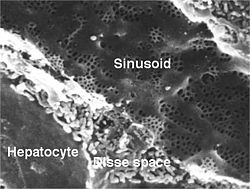

Individual capillaries are part of the capillary bed, an interweaving network of capillaries supplying tissues and organs. The more metabolically active a tissue is, the more capillaries are required to supply nutrients and carry away products of metabolism. There are two types of capillaries: true capillaries, which branch from arterioles and provide exchange between tissue and the capillary blood, and sinusoids, a type of open-pore capillary found in the liver, bone marrow, anterior pituitary gland, and brain circumventricular organs. Capillaries and sinusoids are short vessels that directly connect the arterioles and venules at opposite ends of the beds. Metarterioles are found primarily in the mesenteric microcirculation.[5]

Lymphatic capillaries are slightly larger in diameter than blood capillaries, and have closed ends (unlike the blood capillaries open at one end to the arterioles and open at the other end to the venules). This structure permits interstitial fluid to flow into them but not out. Lymph capillaries have a greater internal oncotic pressure than blood capillaries, due to the greater concentration of plasma proteins in the lymph.[6]

Types

[edit]

Blood capillaries are categorized into three types: continuous, fenestrated, and sinusoidal (also known as discontinuous).

Continuous

[edit]Continuous capillaries are continuous in the sense that the endothelial cells provide an uninterrupted lining, and they only allow smaller molecules, such as water and ions, to pass through their intercellular clefts.[7][8] Lipid-soluble molecules can passively diffuse through the endothelial cell membranes along concentration gradients.[9] Continuous capillaries can be further divided into two subtypes:

- Those with numerous transport vesicles, which are found primarily in skeletal muscles, fingers, gonads, and skin.[10]

- Those with few vesicles, which are primarily found in the central nervous system. These capillaries are a constituent of the blood–brain barrier.[8]

Fenestrated

[edit]Fenestrated capillaries have pores known as fenestrae (Latin for "windows") in the endothelial cells that are 60–80 nanometres (nm) in diameter. They are spanned by a diaphragm of radially oriented fibrils that allows small molecules and limited amounts of protein to diffuse.[11][12] In the renal glomerulus the capillaries are wrapped in podocyte foot processes or pedicels, which have slit pores with a function analogous to the diaphragm of the capillaries. Both of these types of blood vessels have continuous basal laminae and are primarily located in the endocrine glands, intestines, pancreas, and the glomeruli of the kidney.

Sinusoidal

[edit]

Sinusoidal capillaries or discontinuous capillaries are a special type of open-pore capillary, also known as a sinusoid,[13] that have wider fenestrations that are 30–40 micrometres (μm) in diameter, with wider openings in the endothelium.[14] Fenestrated capillaries have diaphragms that cover the pores whereas sinusoids lack a diaphragm and just have an open pore. These types of blood vessels allow red and white blood cells (7.5 μm – 25 μm diameter) and various serum proteins to pass, aided by a discontinuous basal lamina. These capillaries lack pinocytotic vesicles, and therefore use gaps present in cell junctions to permit transfer between endothelial cells, and hence across the membrane. Sinusoids are irregular spaces filled with blood and are mainly found in the liver, bone marrow, spleen, and brain circumventricular organs.[14][15]

Development

[edit]During early embryonic development, new capillaries are formed through vasculogenesis, the process of blood vessel formation that occurs through a novel production of endothelial cells that then form vascular tubes.[16] The term angiogenesis denotes the formation of new capillaries from pre-existing blood vessels and already-present endothelium which divides.[17] The small capillaries lengthen and interconnect to establish a network of vessels, a primitive vascular network that vascularises the entire yolk sac, connecting stalk, and chorionic villi.[18]

Function

[edit]

The capillary wall performs an important function by allowing nutrients and waste substances to pass across it. Molecules larger than 3 nm such as albumin and other large proteins pass through transcellular transport carried inside vesicles, a process which requires them to go through the cells that form the wall. Molecules smaller than 3 nm such as water and gases cross the capillary wall through the space between cells in a process known as paracellular transport.[19] These transport mechanisms allow bidirectional exchange of substances depending on osmotic gradients.[20] Capillaries that form part of the blood–brain barrier only allow for transcellular transport as tight junctions between endothelial cells seal the paracellular space.[21]

Capillary beds may control their blood flow via autoregulation. This allows an organ to maintain constant flow despite a change in central blood pressure. This is achieved by myogenic response, and in the kidney by tubuloglomerular feedback. When blood pressure increases, arterioles are stretched and subsequently constrict (a phenomenon known as the Bayliss effect) to counteract the increased tendency for high pressure to increase blood flow.[22]

In the lungs, special mechanisms have been adapted to meet the needs of increased necessity of blood flow during exercise. When the heart rate increases and more blood must flow through the lungs, capillaries are recruited and are also distended to make room for increased blood flow. This allows blood flow to increase while resistance decreases.[citation needed] Extreme exercise can make capillaries vulnerable, with a breaking point similar to that of collagen.[23]

Capillary permeability can be increased by the release of certain cytokines, anaphylatoxins, or other mediators (such as leukotrienes, prostaglandins, histamine, bradykinin, etc.) highly influenced by the immune system.[24]

Starling equation

[edit]

The transport mechanisms can be further quantified by the Starling equation.[20] The Starling equation defines the forces across a semipermeable membrane and allows calculation of the net flux:

where:

- is the net driving force,

- is the proportionality constant, and

- is the net fluid movement between compartments.

By convention, outward force is defined as positive, and inward force is defined as negative. The solution to the equation is known as the net filtration or net fluid movement (Jv). If positive, fluid will tend to leave the capillary (filtration). If negative, fluid will tend to enter the capillary (absorption). This equation has a number of important physiologic implications, especially when pathologic processes grossly alter one or more of the variables.[citation needed]

According to Starling's equation, the movement of fluid depends on six variables:

- Capillary hydrostatic pressure (Pc)

- Interstitial hydrostatic pressure (Pi)

- Capillary oncotic pressure (πc)

- Interstitial oncotic pressure (πi)

- Filtration coefficient (Kf)

- Reflection coefficient (σ)

Clinical significance

[edit]Disorders of capillary formation as a developmental defect or acquired disorder are a feature in many common and serious disorders. Within a wide range of cellular factors and cytokines, issues with normal genetic expression and bioactivity of the vascular growth and permeability factor vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) appear to play a major role in many of the disorders. Cellular factors include reduced number and function of bone-marrow derived endothelial progenitor cells.[25] and reduced ability of those cells to form blood vessels.[26]

- Formation of additional capillaries and larger blood vessels (angiogenesis) is a major mechanism by which a cancer may help to enhance its own growth. Disorders of retinal capillaries contribute to the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration.

- Reduced capillary density (capillary rarefaction) occurs in association with cardiovascular risk factors[27] and in patients with coronary heart disease.[26]

Therapeutics

[edit]Major diseases where altering capillary formation could be helpful include conditions where there is excessive or abnormal capillary formation such as cancer and disorders harming eyesight; and medical conditions in which there is reduced capillary formation either for familial or genetic reasons, or as an acquired problem.

- In patients with the retinal disorder, neovascular age-related macular degeneration, local anti-VEGF therapy to limit the bio-activity of vascular endothelial growth factor has been shown to protect vision by limiting progression.[28] In a wide range of cancers, treatment approaches have been studied, or are in development, aimed at decreasing tumour growth by reducing angiogenesis.[29]

Blood sampling

[edit]Capillary blood sampling can be used to test for blood glucose (such as in blood glucose monitoring), hemoglobin, pH and lactate.[30][31] It is generally performed by creating a small cut using a blood lancet, followed by sampling by capillary action on the cut with a test strip or small pipette.[32] It is also used to test for sexually transmitted infections that are present in the blood stream, such as HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C, where a finger is lanced and a small amount of blood is sampled into a test tube.[33]

History

[edit]A 13th century manuscript by Ibn Nafis contains the earliest known description of capillaries. The manuscript records Ibn Nafis' prediction of the existence of the capillaries which he described as perceptible passages (manafidh) between pulmonary artery and pulmonary vein. These passages would later be identified by Marcello Malpighi as capillaries. He further states that the heart's two main chambers (right and left ventricles) are separate and that blood cannot pass through the (interventricular) septum.[34][35]

William Harvey did not explicitly predict the existence of capillaries, but he saw the need for some sort of connection between the arterial and venous systems. In 1653, he wrote, "...the blood doth enter into every member through the arteries, and does return by the veins, and that the veins are the vessels and ways by which the blood is returned to the heart itself; and that the blood in the members and extremities does pass from the arteries into the veins (either mediately by an anastomosis, or immediately through the porosities of the flesh, or both ways) as before it did in the heart and thorax out of the veins, into the arteries..."[36]

Marcello Malpighi was the first to observe directly and correctly describe capillaries, discovering them in a frog's lung 8 years later, in 1661.[37]

August Krogh discovered how capillaries provide nutrients to animal tissue. For his work he was awarded the 1920 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[38] His 1922 estimate that total length of capillaries in a human body is as long as 100,000 km, had been widely adopted by textbooks and other secondary sources. This estimate was based on figures he gathered from "an extraordinarily large person".[39] More recent estimates give a number between 9,000 and 19,000 km.[40][39]

See also

[edit]- Blood–air barrier, also known as alveolar–capillary barrier – Membrane separating alveolar air from blood in lung capillaries

- Capillary refill – Medical term

- Hagen–Poiseuille equation – Law describing the pressure drop in an incompressible and Newtonian fluid

- Surface chemistry of microvasculature

References

[edit]- ^ Federative International Committee on Anatomical Terminology (2008). Terminologia Histologica: International Terms for Human Cytology and Histology. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7817-6610-4.

- ^ "Structure and Function of Blood Vessels | Anatomy and Physiology II". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Maton, Anthea (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 87, 114, 120. ISBN 978-0-13-981176-0.

- ^ a b "Capillary". Online Etymology Dictionary. 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Sakai, T; Hosoyamada, Y (2013). "Are the precapillary sphincters and metarterioles universal components of the microcirculation? An historical review". The Journal of Physiological Sciences. 63 (5): 319–31. doi:10.1007/s12576-013-0274-7. PMC 3751330. PMID 23824465.

- ^ Guyton, Arthur C.; Hall, John Edward (2006). "The Microcirculation and the Lymphatic System". Textbook of Medical Physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-8089-2317-6.

- ^ Stamatovic, S. M.; Johnson, A. M.; Keep, R. F.; Andjelkovic, A. V. (2016). "Junctional proteins of the blood-brain barrier: New insights into function and dysfunction". Tissue Barriers. 4 (1) e1154641. doi:10.1080/21688370.2016.1154641. PMC 4836471. PMID 27141427.

- ^ a b Wilhelm, I.; Suciu, M.; Hermenean, A.; Krizbai, I. A. (2016). "Heterogeneity of the blood-brain barrier". Tissue Barriers. 4 (1) e1143544. doi:10.1080/21688370.2016.1143544. PMC 4836475. PMID 27141424.

- ^ Sarin, H. (2010). "Overcoming the challenges in the effective delivery of chemotherapies to CNS solid tumors". Therapeutic Delivery. 1 (2): 289–305. doi:10.4155/tde.10.22. PMC 3234205. PMID 22163071.

- ^ Michel, C. C. (2012). "Electron tomography of vesicles". Microcirculation. 19 (6): 473–6. doi:10.1111/j.1549-8719.2012.00191.x. PMID 22574942. S2CID 205759387.

- ^ Histology image:22401lba from Vaughan, Deborah (2002). A Learning System in Histology: CD-ROM and Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195151732.

- ^ Pavelka, Margit; Roth, Jürgen (2005). "Fenestrated Capillary". Functional Ultrastructure: An Atlas of Tissue Biology and Pathology. Vienna: Springer. p. 232. doi:10.1007/3-211-26392-6_120. ISBN 978-3-211-26392-1.

- ^ "Histology Laboratory Manual". www.columbia.edu.

- ^ a b Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human Anatomy. McGraw-Hill. pp. 568–569. ISBN 978-0-07-122207-5.

- ^ Gross, P. M (1992). "Chapter 31: Circumventricular organ capillaries". Circumventricular Organs and Brain Fluid Environment - Molecular and Functional Aspects. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 91. pp. 219–33. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)62338-9. ISBN 978-0-444-81419-7. PMID 1410407.

- ^ John S. Penn (11 March 2008). Retinal and Choroidal Angiogenesis. Springer. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-1-4020-6779-2. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2000). "Endoderm". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-243-7. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Schoenwolf, Gary C. (2015). Larsen's human embryology (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. p. 306. ISBN 978-1-4557-0684-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sukriti, S; Tauseef, M; Yazbeck, P; Mehta, D (2014). "Mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability". Pulmonary Circulation. 4 (4): 535–551. doi:10.1086/677356. PMC 4278616. PMID 25610592.

- ^ a b Nagy, JA; Benjamin, L; Zeng, H; Dvorak, AM; Dvorak, HF (2008). "Vascular permeability, vascular hyperpermeability and angiogenesis". Angiogenesis. 11 (2): 109–119. doi:10.1007/s10456-008-9099-z. PMC 2480489. PMID 18293091.

- ^ Bauer, HC; Krizbai, IA; Bauer, H; Traweger, A (2014). ""You Shall Not Pass"-tight junctions of the blood brain barrier". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 8: 392. doi:10.3389/fnins.2014.00392. PMC 4253952. PMID 25520612.

- ^ Boulpaep, Emile L. (2017). "The Microcirculation". In Boron, Walter F.; Boulpaep, Emile L. (eds.). Medical Physiology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. p. 481. ISBN 978-1-4557-4377-3.

- ^ West, J. B. (2006). "Vulnerability of pulmonary capillaries during severe exercise". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 40 (10): 821. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.028886. ISSN 1473-0480. PMC 2465077. PMID 17021008.

- ^ Yunfei, Chi; Xiangyu, Liu (9 April 2021), Jiake, Chai (ed.), "A narrative review of changes in microvascular permeability after burn", Annals of Translational Medicine, 9 (8): 719, doi:10.21037/atm-21-1267, PMC 8106041, PMID 33987417

- ^ Gittenberger-De Groot, Adriana C.; Winter, Elizabeth M.; Poelmann, Robert E. (2010). "Epicardium derived cells (EPDCs) in development, cardiac disease and repair of ischemia". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 14 (5): 1056–60. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01077.x. PMC 3822740. PMID 20646126.

- ^ a b Lambiase, P. D.; Edwards, RJ; Anthopoulos, P; Rahman, S; Meng, YG; Bucknall, CA; Redwood, SR; Pearson, JD; Marber, MS (2004). "Circulating Humoral Factors and Endothelial Progenitor Cells in Patients with Differing Coronary Collateral Support" (PDF). Circulation. 109 (24): 2986–92. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000130639.97284.EC. PMID 15184289. S2CID 12041051.

- ^ Noon, J P; Walker, B R; Webb, D J; Shore, A C; Holton, D W; Edwards, H V; Watt, G C (1997). "Impaired microvascular dilatation and capillary rarefaction in young adults with a predisposition to high blood pressure". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 99 (8): 1873–9. doi:10.1172/JCI119354. PMC 508011. PMID 9109431.

- ^ Bird, Alan C. (2010). "Therapeutic targets in age-related macular disease". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 120 (9): 3033–41. doi:10.1172/JCI42437. PMC 2929720. PMID 20811159.

- ^ Cao, Yihai (2009). "Tumor angiogenesis and molecular targets for therapy". Frontiers in Bioscience. 14 (14): 3962–73. doi:10.2741/3504. PMID 19273326.

- ^ Krleza, Jasna Lenicek; Dorotic, Adrijana; Grzunov, Ana; Maradin, Miljenka (15 October 2015). "Capillary blood sampling: national recommendations on behalf of the Croatian Society of Medical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine". Biochemia Medica. 25 (3): 335–358. doi:10.11613/BM.2015.034. ISSN 1330-0962. PMC 4622200. PMID 26524965.

- ^ Moro, Christian; Bass, Jessica; Scott, Anna Mae; Canetti, Elisa F.D. (19 January 2017). "Enhancing capillary blood collection: The influence of nicotinic acid and nonivamide". Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 31 (6) e22142. doi:10.1002/jcla.22142. ISSN 0887-8013. PMC 6817299. PMID 28102549.

- ^ "Managing diabetes:Check your blood glucose levels". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, US National Institutes of Health. 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "Fettle - How to take a blood sample". Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ West, John B. (2008). "Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age". Journal of Applied Physiology. 105 (6): 1877–1880. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91171.2008. ISSN 8750-7587. PMC 2612469. PMID 18845773.

- ^ Aloud, Abdurahim (16 January 2017). "Ibn al-Nafis and the discovery of the pulmonary circulation". The Southwest Respiratory and Critical Care Chronicles. 5 (17): 71–73. doi:10.12746/swrccc2017.0517.229. ISSN 2325-9205.

- ^ Harvey, William (1653). On the motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals. pp. 59–60. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011.

- ^ Cliff, Walter John (1976). Blood Vessels. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8357-7328-7.

- ^ "August Krogh". July 2023.

- ^ a b Poole, David C; Kano, Yutaka; Shunsaku, Koga; Musch, Timothy I. "August Krogh: Muscle capillary function and oxygen delivery". p. 8. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ Kurzgesagt. "Sources - 100K Blood Vessels". sites.google.com. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 00903loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- The Microcirculatory Society, Inc.

- The Histology Guide – Capillaries

Capillary

View on GrokipediaTerminology

Etymology

The word capillary originates from the Latin adjective capillāris, meaning "of or pertaining to hair," which itself derives from capillus, denoting "hair" (particularly of the head), ultimately tracing back to caput, meaning "head."[6][7] This term entered English in the mid-17th century, initially describing structures resembling fine hairs in slenderness and elongation, a usage that aligned with early observations of the minute blood vessels now known as capillaries.[8][9] The anatomical application reflects their hair-like appearance.Definition and Characteristics

Capillaries are the smallest blood vessels in the circulatory system, forming microscopic networks that connect arterioles to venules and serve as the primary site for the exchange of oxygen, nutrients, carbon dioxide, and waste products between blood and surrounding tissues.[1] These vessels are characterized by their extremely thin walls, which consist solely of a single layer of flattened endothelial cells, allowing for efficient diffusion across the vessel barrier.[3] Unlike larger arteries and veins, capillaries lack smooth muscle cells and elastic fibers, relying instead on the surrounding arterioles for blood flow regulation.[3] Structurally, the capillary wall includes the endothelium supported by a thin basement membrane, with occasional pericytes embedded within or around this membrane to provide structural support and regulate permeability.[1] Capillaries typically measure 5 to 10 micrometers in diameter, just wide enough to allow red blood cells to pass through in single file, which minimizes the diffusion distance and enhances exchange efficiency.[10] Their total surface area is vast due to extensive branching, estimated at around 800–1,000 square meters in an adult human, facilitating the high-volume transfer essential for tissue perfusion.[11] Functionally, capillaries enable passive diffusion of small solutes (less than 3 nanometers in size) through endothelial junctions or fenestrations, while larger molecules like proteins require specialized transporters or vesicular transport mechanisms.[1] This selective permeability is crucial for maintaining fluid balance and preventing excessive leakage, with blood flow through capillary beds controlled by precapillary sphincters to match metabolic demands of tissues.[12] In aggregate, these characteristics make capillaries indispensable for homeostasis, as disruptions in their structure or function can lead to impaired nutrient delivery and tissue pathology.[2]Anatomy

Microscopic Structure

Capillaries are the smallest blood vessels in the circulatory system, typically measuring 5 to 10 micrometers in diameter, which is just wide enough for red blood cells to pass through in single file.[2] Their walls consist of a single layer of flattened endothelial cells, forming a simple squamous epithelium that lines the lumen and facilitates the exchange of substances between blood and tissues.[1] This endothelial layer is supported by a thin basement membrane composed of extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen type IV and laminin, which provides structural integrity without impeding diffusion.[13] Under light microscopy, capillaries appear as thin, tube-like structures with minimal visible wall thickness, often requiring special stains like periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) to highlight the basement membrane.[1] Electron microscopy reveals greater detail, showing the endothelial cells connected by tight junctions or adherens junctions, with occasional fenestrations or gaps depending on the capillary type, though the general structure remains a continuous barrier in most tissues.[1] Pericytes, elongated contractile cells embedded in the basement membrane, wrap around the exterior of capillaries at irregular intervals, comprising about 1 per 100 endothelial cells and contributing to vessel stability and regulation.[14] The overall length of capillaries in the human body is estimated at around 40,000 kilometers, forming an extensive network that maximizes surface area for exchange, with a total cross-sectional area vastly exceeding that of larger vessels.[2] In histological preparations, such as thin sections fixed with glutaraldehyde and stained with uranyl acetate, the capillary wall measures approximately 0.5 micrometers thick, underscoring its role as a semi-permeable interface.[1] No smooth muscle layer is present, distinguishing capillaries from arterioles and venules, and their sparse connective tissue support allows for flexibility and proximity to tissue cells.[13]Continuous Capillaries

Continuous capillaries represent the most prevalent type of capillary throughout the body, comprising the majority of the approximately 10 billion capillaries in a typical human adult. These vessels feature a complete, uninterrupted layer of endothelial cells joined by tight junctions, which form a continuous barrier without intercellular gaps, pores, or fenestrations.[10][15] The endothelial lining is supported by a continuous basal lamina, and pericytes intermittently wrap around the exterior, providing structural support and regulatory influence over endothelial function.[16] This architecture results in relatively low permeability compared to other capillary types, restricting the passage of substances primarily to small molecules such as water, ions, and lipid-soluble compounds via diffusion through the endothelial cells or narrow intercellular clefts approximately 1 μm in length and 0.5–1 nm wide.[17][18] In terms of function, continuous capillaries facilitate the essential exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products between blood and surrounding tissues through paracellular diffusion for hydrophilic solutes and transcellular routes for larger entities. Transport mechanisms include transcytosis via vesicles and caveolae—small invaginations of the endothelial plasma membrane—that enable the shuttling of proteins, peptides, and other macromolecules across the endothelium without disrupting the barrier integrity.[16] Pinocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis further contribute to this selective permeability, ensuring controlled nutrient delivery while preventing unrestricted leakage.[19] In specialized contexts, such as the blood-brain barrier in the central nervous system, continuous capillaries exhibit enhanced tight junction complexity, minimal pinocytic activity, and efflux transporters like P-glycoprotein, which actively exclude potentially harmful substances from neural tissue.[20] These capillaries are distributed across a wide array of tissues, including skeletal and cardiac muscle, connective tissue, skin, lungs, and the nervous system, where they support routine metabolic demands.[21] In the lungs, for instance, they enable efficient gas exchange while maintaining barrier selectivity to avoid fluid leakage into alveoli. Their prevalence and regulated permeability underscore their role in maintaining tissue homeostasis, with disruptions implicated in conditions like edema or barrier dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases.[1]Fenestrated Capillaries

Fenestrated capillaries represent a subtype of continuous capillaries distinguished by the presence of fenestrations—small pores or openings in the endothelial cells that permit enhanced transendothelial transport. These structures are essential in tissues where rapid exchange of fluids, solutes, and small molecules between blood and interstitium is required. Unlike non-fenestrated continuous capillaries, the fenestrations increase permeability while maintaining a barrier function through thin diaphragms spanning the pores.[1] The endothelial lining of fenestrated capillaries consists of a single layer of flattened squamous cells, underpinned by a basement membrane and sporadically supported by pericytes. Each fenestration typically measures 60-80 nm in diameter and is sealed by a non-membranous diaphragm approximately 3-5 nm thick, composed of radially oriented protein fibrils such as plasmalemmal vesicles-derived components. This diaphragm selectively restricts the passage of larger macromolecules while allowing water, ions, and small solutes (up to ~40-60 kDa) to diffuse freely, contributing to a hydraulic conductivity approximately 40-50 times greater than that of continuous capillaries.[22][23][1][24] The overall capillary diameter ranges from 5-10 μm, optimizing surface area for exchange without compromising structural integrity.[22][23][1] These capillaries are predominantly located in organs involved in filtration, absorption, and secretion. In the kidneys, they form the glomerular capillary network, enabling ultrafiltration of plasma during urine formation. They are also abundant in the small intestine's villi and gallbladder mucosa, where they support nutrient and fluid absorption, and in endocrine glands such as the pancreas and thyroid, facilitating hormone release into the bloodstream. Additional sites include the choroid plexus of the brain, underscoring their role in specialized barrier functions across vascular beds.[25][23][22] Physiologically, fenestrated capillaries play a critical role in maintaining homeostasis through regulated permeability. In renal glomeruli, the fenestrations, combined with podocyte slit diaphragms, achieve a filtration barrier that excludes albumin (66 kDa) while permitting smaller molecules, with a sieving coefficient near 1 for substances under 10 kDa. This selective filtration prevents edema and supports efficient waste removal. In absorptive tissues like the intestine, the pores enhance the uptake of glucose, amino acids, and lipids post-digestion. Disruptions in fenestration integrity, such as in diabetic nephropathy, can lead to proteinuria, highlighting their clinical significance.[22][1]Sinusoidal Capillaries

Sinusoidal capillaries, also known as sinusoids, represent a specialized subtype of discontinuous capillaries distinguished by their irregular, widened lumens and highly permeable walls. Unlike continuous or fenestrated capillaries, they feature large intercellular gaps between endothelial cells, often exceeding 100 nm in width, and a discontinuous or entirely absent basement membrane, which collectively enable the passage of macromolecules, plasma proteins, and even intact blood cells such as erythrocytes and leukocytes. This structure is composed of a single layer of flattened endothelial cells that lack tight junctions, further enhancing permeability while maintaining a barrier function selective to the needs of specific tissues.[26][10] These capillaries are predominantly located in organs requiring extensive filtration, blood cell production, or metabolic processing, including the liver (hepatic sinusoids), spleen, bone marrow, lymph nodes, adrenal glands, and other endocrine glands such as the pituitary. In the liver, sinusoids form a complex network surrounding hepatocytes, receiving blood from the hepatic portal vein and hepatic artery to facilitate nutrient absorption and toxin detoxification. Similarly, in the bone marrow, they allow the release of newly formed blood cells into circulation, while in the spleen, they support immune surveillance by permitting the passage of antigens and damaged cells for phagocytosis. Their strategic positioning in these sites underscores their role in high-volume exchange environments.[10][26][27] The primary function of sinusoidal capillaries is to support rapid and extensive bidirectional exchange between blood and interstitial fluid, accommodating slower blood flow velocities that prolong contact time for diffusion and filtration. This high permeability is crucial for physiological processes such as the liver's uptake of chylomicron remnants and bilirubin, the spleen's clearance of senescent red blood cells, and the bone marrow's egress of hematopoietic progenitors. In hepatic sinusoids, specialized endothelial cells are often interspersed with resident macrophages known as Kupffer cells, which enhance phagocytic activity against pathogens and debris, thereby integrating vascular exchange with immune defense. Overall, their design optimizes organ-specific homeostasis by prioritizing permeability over selective restriction.[26][10][28]Formation and Development

Embryonic Development

The embryonic development of capillaries begins with vasculogenesis, the de novo formation of blood vessels from endothelial precursor cells known as angioblasts, which differentiate from mesodermal progenitors during early gastrulation. In mammalian embryos, this process initiates in the extraembryonic yolk sac around embryonic day 7.0-7.5 in mice (corresponding to approximately 3 weeks in human gestation), where hemangioblasts—bipotent progenitors giving rise to both endothelial and hematopoietic cells—aggregate into blood islands. These islands consist of an inner core of primitive erythroblasts surrounded by endothelial cells that fuse to form a primitive capillary plexus, establishing the foundational vascular network essential for nutrient exchange and embryonic survival.[29][30] Key molecular regulators drive this initial vasculogenesis, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor VEGFR-2 (Flk-1/KDR), which are critical for angioblast specification and migration. Transcription factors such as TAL1 (SCL), GATA2, and LMO2 orchestrate endothelial differentiation from lateral plate mesoderm, while fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) support proliferation and survival of these precursors. Intraembryonically, vasculogenesis extends to the splanchnic mesoderm by embryonic day 8.0 in mice, forming paired dorsal aortae and cardinal veins from coalescing angioblasts, with the primitive plexus maturing into capillary beds that perfuse emerging embryonic tissues. Disruptions in these pathways, as seen in VEGF or TAL1 knockout models, result in severe vascular defects and embryonic lethality, underscoring their indispensable role.[29][31] As embryogenesis progresses, angiogenesis— the sprouting and branching of new vessels from pre-existing ones—supplements vasculogenesis to expand and refine the capillary network, particularly from embryonic day 8.5 onward in mice. Endothelial tip cells, guided by VEGF gradients and Delta-Notch signaling, lead filopodial extensions to form sprouts that connect and remodel into hierarchical capillary structures, ensuring adequate oxygenation of rapidly growing organs like the brain and heart. This phase involves pericyte recruitment for vessel stabilization and lumen formation, transforming rudimentary capillaries into functional units capable of fluid and solute exchange. In humans, this corresponds to weeks 4-8 of gestation, when the chorioallantoic placenta integrates with embryonic capillaries to support fetal circulation.[32][33]Adult Angiogenesis and Remodeling

In adults, angiogenesis—the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones—primarily occurs in response to physiological demands such as wound healing, tissue repair, and exercise-induced muscle adaptation, or pathological conditions like cancer and ischemia. Unlike the extensive vascularization during embryonic development, adult angiogenesis is tightly regulated and episodic, maintaining vascular quiescence through balanced pro- and anti-angiogenic signals.[34] The process begins with the activation of endothelial cells (ECs) in existing capillaries or venules, triggered by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) that upregulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), the principal stimulator of angiogenesis. Sprouting angiogenesis, the dominant mechanism in adults, involves the degradation of the basement membrane by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) released from ECs and recruited inflammatory cells, allowing tip cells to lead filopodial extensions toward angiogenic cues.[34] Stalk cells proliferate behind the tip cells, forming a lumenized sprout that anastomoses with neighboring vessels to establish perfusion; this is followed by recruitment of pericytes and smooth muscle cells for vessel stabilization via platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) signaling.[34] In parallel, intussusceptive angiogenesis enables rapid vascular remodeling without proliferation, where transcapillary pillars form and split existing vessels, enhancing network complexity in response to hemodynamic changes.[35] Capillary remodeling in adults encompasses pruning of inefficient branches, diameter adjustments, and network reorganization to optimize oxygen delivery and shear stress distribution.[36] Flow-induced shear stress activates mechanosensors like PECAM-1 and VEGFR2 in ECs, promoting nitric oxide (NO) production via endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which supports vessel dilation and stabilization of high-flow segments while inducing regression in low-flow ones through thrombospondin-1 and other inhibitors.[37] This angioadaptation ensures metabolic efficiency; for instance, in skeletal muscle during exercise, capillary density can increase by 10–25% through coordinated sprouting and remodeling, correlating with enhanced VEGF expression.[36][38] Pathological remodeling, as in tumors, often results in leaky, tortuous vessels due to excessive VEGF and imbalanced Ang-2/Ang-1 ratios, impairing function.Physiology

Exchange Mechanisms

Capillary exchange primarily occurs through three key mechanisms: diffusion, transcytosis, and bulk flow, which collectively facilitate the transfer of gases, nutrients, solutes, and fluid between the blood plasma and interstitial spaces. These processes are optimized by the thin structure of the capillary endothelium, typically 0.3–1 μm thick, and vary depending on the capillary type and tissue demands.[39][40] Diffusion is the dominant mechanism for small molecules, allowing passive movement down concentration gradients across the capillary wall. Lipid-soluble substances, such as oxygen and carbon dioxide, readily cross the phospholipid bilayer of endothelial cells via simple diffusion, enabling rapid gas exchange in tissues like muscles and lungs. Water-soluble molecules, including ions, glucose, and amino acids, traverse via paracellular pathways through intercellular clefts (about 0.6–0.7 nm wide in continuous capillaries) or through fenestrations and larger pores in specialized capillaries. This selective permeability ensures efficient nutrient delivery while restricting larger entities, with diffusion rates influenced by molecular size, charge, and solubility.[41][42][43] Transcytosis, or vesicular transport, handles the transcellular movement of larger or impermeable molecules, such as albumin, immunoglobulins, and some hormones. Endothelial cells form vesicles—often caveolae (flask-shaped invaginations 50–70 nm in diameter)—that engulf extracellular material via receptor-mediated endocytosis on the luminal side, traverse the cytoplasm, and release contents via exocytosis on the abluminal side. This process is energy-dependent and regulated by signaling pathways, playing a critical role in maintaining homeostasis; for instance, in the blood-brain barrier, it limits paracellular leakage while permitting selective macromolecular transport. Clathrin-coated vesicles may also contribute in specific contexts, though caveolae predominate in most systemic capillaries.[44][45][46] Bulk flow provides a convective pathway for fluid and accompanying small solutes, driven by pressure differences across the endothelium. In continuous capillaries, this occurs through small intercellular clefts, while fenestrated and sinusoidal capillaries feature diaphragmed or ungapped pores (up to 100 nm) that enhance filtration rates, as seen in renal glomeruli where up to 180 liters of fluid filter daily. Although integral to overall exchange, bulk flow's quantitative aspects, including net filtration, are determined by transendothelial pressures and oncotic forces.[40][39][42]Fluid Dynamics and Starling Equation

The fluid dynamics within capillaries are characterized by laminar flow due to their small diameters (typically 5–10 μm) and low Reynolds numbers, which ensure that inertial forces are negligible compared to viscous forces. This steady, non-turbulent flow is primarily governed by Poiseuille's law, which quantifies the volume flow rate through a cylindrical tube as , where is the radius, is the pressure difference along the length , and is the fluid viscosity.[47] In capillaries, blood behaves as a non-Newtonian fluid owing to the high hematocrit and deformation of red blood cells, but Poiseuille's law provides a useful approximation for understanding how flow velocity decreases dramatically toward the periphery, averaging around 0.3–1 mm/s, facilitating efficient nutrient and gas exchange.[48] The pressure gradient driving this flow originates from the arteriolar resistance, with hydrostatic pressure dropping from approximately 35 mmHg at the arterial end to 15 mmHg at the venous end of a typical systemic capillary.[40] Capillary fluid dynamics extend beyond bulk flow to the transvascular exchange of fluid between plasma and interstitial space, which is critical for maintaining tissue homeostasis. This exchange occurs via filtration and reabsorption across the endothelial wall, influenced by Starling forces that balance hydrostatic and oncotic pressures. The seminal Starling equation, formulated by Ernest Henry Starling in 1896, describes the net fluid flux per unit surface area as: where is the filtration coefficient (reflecting hydraulic conductivity and surface area), and are capillary and interstitial hydrostatic pressures, is the reflection coefficient for proteins (indicating endothelial permeability to solutes), and and are capillary and interstitial oncotic pressures.[49] Hydrostatic pressure favors filtration out of the capillary, while oncotic pressure—primarily from plasma proteins like albumin—promotes reabsorption; typically, net filtration occurs at the arterial end (where ) and net reabsorption at the venous end, with any excess interstitial fluid drained by lymphatics.[40] Refinements to the classical Starling equation, such as the revised model incorporating the endothelial glycocalyx layer, emphasize that subglycocalyx oncotic pressure plays a dominant role in preventing edema by creating a barrier that sustains the oncotic gradient near the endothelial junction.[50] This glycocalyx model, supported by experimental evidence from microvascular studies, highlights how disruptions (e.g., in inflammation) can shift the balance toward excessive filtration, underscoring the equation's application in pathophysiology. Quantitative estimates indicate that under normal conditions, about 20–25 liters of fluid filter daily across capillaries, with roughly 90% reabsorbed and the remainder returned via lymph.[49] These dynamics ensure precise regulation of extracellular fluid volume, with deviations linked to conditions like edema or hypovolemia.Clinical Aspects

Pathophysiology

Capillary pathophysiology encompasses disruptions in the structural integrity, permeability, and regulatory functions of these microvessels, leading to impaired nutrient exchange, tissue edema, and organ dysfunction. In inflammatory conditions such as sepsis, endothelial cells in capillaries release mediators like histamine, nitric oxide, and cytokines, which increase vascular permeability by disrupting tight junctions and actin cytoskeleton, resulting in fluid and protein leakage into the interstitium. This contributes to hypotension, third-spacing of fluids, and multi-organ failure.[1] Systemic capillary leak syndrome represents a severe form of permeability dysfunction, where episodic or idiopathic increases in endothelial gap formation allow massive protein-rich fluid extravasation, causing hypoalbuminemia, hemoconcentration, and life-threatening edema in organs like the lungs and heart. The underlying mechanisms involve endothelial glycocalyx degradation and inflammatory cytokine storms, often triggered by infections, malignancies, or monoclonal gammopathies.[51] In chronic metabolic disorders like diabetes mellitus, diabetic microangiopathy induces capillary basement membrane thickening, pericyte loss, and endothelial dysfunction, primarily driven by hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and advanced glycation end-products, which impair vasodilation and promote leakage in retinal, renal, and peripheral capillaries. This leads to retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy through localized ischemia and hemorrhage. Similarly, in atherosclerosis, prolonged exposure to risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia causes endothelial activation, oxidative stress, and capillary rarefaction—a reduction in capillary density due to pericyte apoptosis and impaired angiogenesis—exacerbating tissue hypoxia even after large-vessel revascularization.[52][53] Hereditary conditions like hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) involve genetic mutations in TGF-β signaling pathways, leading to fragile, dilated capillaries prone to rupture and arteriovenous malformations, resulting in recurrent epistaxis, mucocutaneous telangiectasias, and visceral bleeding. In neoplastic processes, aberrant angiogenesis driven by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) overexpression produces leaky, tortuous capillaries that support tumor growth but cause peritumoral edema and metastasis facilitation.[1]Diagnostics and Therapeutics

Diagnostics of capillary dysfunction often rely on non-invasive techniques to assess microvascular structure and function. Nailfold capillaroscopy, a simple and safe method, allows direct visualization of nailfold capillaries using a microscope or dermatoscope to evaluate morphology, density, and blood flow patterns, aiding in the diagnosis of connective tissue diseases and other microvascular abnormalities.[54] In systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS), diagnosis is based on recurrent episodes of severe hypotension, hemoconcentration (elevated hematocrit), and generalized edema, confirmed by exclusion of other causes and sometimes supported by monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS).[55] For cerebral small vessel disease (SVD), advanced imaging such as arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI detects capillary dysfunction through impaired perfusion and elevated capillary transit time heterogeneity, correlating with cognitive decline.[56] In coronary microvascular disease, diagnostic approaches include coronary flow reserve (CFR) measurement via positron emission tomography (PET) or invasive catheterization to quantify capillary-level flow impairment, often revealing reduced CFR (<2.0) indicative of endothelial dysfunction.[57] Impedance cardiography provides hemodynamic insights in acute capillary leak scenarios, monitoring thoracic fluid content and stroke volume to guide fluid management.[58] Therapeutics targeting capillaries focus on stabilizing endothelial barriers, improving perfusion, and addressing underlying causes in specific disorders. For SCLS, acute attacks are managed supportively with cautious intravenous fluids and albumin infusions to counteract hypovolemia without exacerbating leakage, while prophylactic therapy with oral terbutaline (a β2-agonist) and theophylline (a phosphodiesterase inhibitor) reduces attack frequency by enhancing vascular tone, achieving remission in many patients.[59] Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has shown efficacy in refractory cases by modulating endothelial permeability.[60] In coronary microvascular disease, β-blockers (e.g., nebivolol) and calcium channel blockers alleviate vasospasm and improve capillary dilation, while statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) enhance endothelial function by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress, leading to symptom improvement.[57] Emerging stem cell therapies, such as intracoronary infusion of CD34+ cells, promote angiogenesis and capillary repair in refractory microvascular angina, with trials reporting enhanced CFR and reduced angina episodes.[61] For cerebral SVD involving capillary pathways, blood pressure control with ACEIs or ARBs prevents progression, while antiplatelet agents like aspirin reduce microvascular thrombosis; investigational therapies include nitric oxide donors and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors to boost capillary perfusion, showing promise in preclinical models for mitigating stroke risk.[62] In sepsis-related capillary leak, experimental approaches target permeability regulators like TRPV4 channels with selective antagonists to limit edema formation, though clinical translation remains limited.[63] Emerging therapies as of 2025 include engineered exosomes for treating capillary-related neovascularization in ocular diseases such as diabetic retinopathy and potential interventions targeting capillary dysfunction in neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's disease.[64][65]History

Early Observations

The earliest conceptualizations of capillary-like structures emerged in medieval Islamic medicine, where the physician Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) described the pulmonary circulation in his commentary on Avicenna's Canon of Medicine. He proposed that blood from the right ventricle passes through the lungs via minute, invisible channels—effectively predicting capillaries—before reaching the left ventricle, challenging Galen's erroneous view of direct ventricular interconnection.[66] In the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) made some of the first direct observations of fine vascular networks during anatomical dissections. Through detailed sketches and notes, he depicted small vessels branching from arteries and rejoining veins, inferring their role in connecting the two systems and facilitating blood distribution, though limited by the absence of magnification tools.[67] The definitive gap in understanding circulation was highlighted by William Harvey's 1628 treatise De Motu Cordis, which established systemic blood flow but left unexplained how arteries and veins interconnect, as these links were imperceptible to the naked eye. This puzzle was resolved in 1661 by Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694), who employed an early compound microscope—designed by Galileo—to examine frog lung tissue. Malpighi observed a continuous network of minute vessels, which he termed "capillaries," linking arterioles to venules and confirming blood's unbroken circuit through the lungs and other organs. His findings, published in De Pulmonibus Observationes Anatomicae, marked the first microscopic visualization of capillaries and revolutionized vascular anatomy.[68][67]Key Scientific Advancements

The discovery of capillaries as the microscopic connections between arteries and veins represented a pivotal advancement in understanding blood circulation. In 1661, Italian anatomist Marcello Malpighi first observed these vessels using an early compound microscope while examining frog lung tissue, describing them as a network of fine tubules that completed the circulatory loop proposed by William Harvey three decades earlier.[67] This observation resolved a long-standing anatomical puzzle but initially sparked debates about the capillary wall's composition, with some early microscopists like Antonie van Leeuwenhoek describing them as simple porous tubes without clear cellular detail.[69] Advancements in microscopy during the 19th century clarified the cellular nature of the capillary endothelium. In the 1830s, Theodor Schwann, a founder of cell theory, proposed that capillaries were lined by an inner layer of cells, a view initially contested but later supported by observations using silver nitrate staining.[70] By the mid-1800s, anatomists such as Friedrich von Recklinghausen confirmed this lining as a continuous monolayer of flattened cells, distinguishing capillaries from larger vessels. In 1865, Swiss anatomist Wilhelm His coined the term "endothelium" to describe this specialized lining, marking a consensus on its basic structure after over two centuries of debate.[71] Functional insights emerged in the late 19th century with Ernest Henry Starling's formulation of the principles governing fluid exchange across capillary walls. In 1896, Starling demonstrated through experiments on frog capillaries that net fluid movement—filtration at the arterial end and reabsorption at the venous end—results from the balance of hydrostatic and oncotic pressures, as encapsulated in what became known as the Starling equation.[49] This hypothesis provided a mechanistic explanation for interstitial fluid homeostasis and laid the foundation for modern microvascular physiology. A major leap in understanding capillary regulation came in the early 20th century through the work of Danish physiologist August Krogh. In 1919, Krogh showed that skeletal muscle capillaries actively open and close in response to metabolic demands, particularly oxygen needs, via a "motor mechanism" involving local vasoactive factors rather than passive flow alone.[72] This discovery, for which he received the 1920 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, highlighted the dynamic adaptability of the capillary bed and integrated anatomical findings with quantitative measurements of oxygen diffusion capacity. Subsequent electron microscopy studies in the mid-20th century further refined capillary classification into continuous, fenestrated, and sinusoidal types, revealing specialized endothelial features like pores and diaphragms that enhance selective permeability.[73]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/capillary

![{\displaystyle J_{v}=K_{f}[(P_{c}-P_{i})-\sigma (\pi _{c}-\pi _{i})],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/755d10c800dda74df993f593ebe3a461e19a7154)