Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Acer rubrum

View on Wikipedia

| Red maple | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Sapindaceae |

| Genus: | Acer |

| Section: | Acer sect. Rubra |

| Species: | A. rubrum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Acer rubrum | |

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

List

| |

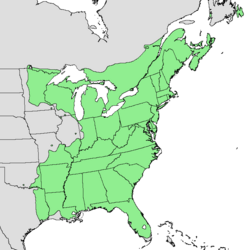

Acer rubrum, the red maple, also known as swamp maple, water maple, or soft maple, is one of the most common and widespread deciduous trees of eastern and central North America. The U.S. Forest Service recognizes it as the most abundant native tree in eastern North America.[4] The red maple ranges from southeastern Manitoba around the Lake of the Woods on the border with Ontario and Minnesota, east to Newfoundland, south to Florida, and southwest to East Texas. Many of its features, especially its leaves, are quite variable in form. At maturity, it often attains a height around 30 m (100 ft). Its flowers, petioles, twigs, and seeds are all red to varying degrees. Among these features, however, it is best known for its brilliant deep scarlet foliage in autumn.

Over most of its range, red maple is adaptable to a very wide range of site conditions, perhaps more so than any other tree in eastern North America. It can be found growing in swamps, on poor, dry soils, and almost anywhere in between. It grows well from sea level to about 900 m (3,000 ft). Due to its attractive fall foliage and pleasing form, it is often used as a shade tree for landscapes. It is used commercially on a small scale for maple syrup production and for its medium to high quality lumber. It is also the state tree of Rhode Island. The red maple can be considered weedy or even invasive in young, highly disturbed forests, especially frequently logged forests. In a mature or old-growth northern hardwood forest, red maple only has a sparse presence, while shade-tolerant trees such as sugar maples, beeches, and hemlocks thrive. By removing red maple from a young forest recovering from disturbance, the natural cycle of forest regeneration is altered, changing the diversity of the forest for centuries to come.[5]

Description

[edit]

Though A. rubrum is sometimes easy to identify, it is highly changeable in morphological characteristics. It is a medium to large sized tree, reaching heights of 27 to 38 m (90 to 120 ft) and exceptionally over 41 m (135 ft) in the southern Appalachians where conditions favor its growth. The leaves are usually 9 to 11 cm (3+1⁄2 to 4+1⁄4 in) long on a full-grown tree. The trunk diameter often ranges from 46 to 88 cm (18 to 35 in); depending on the growing conditions, however, open-grown trees can attain diameters of up to 153 cm (60 in). The trunk remains free of branches until some distance up the tree on forest grown trees, while individuals grown in the open are shorter and thicker with a more rounded crown. Trees on poorer sites often become malformed and scraggly.[6] Generally the crown is irregularly ovoid with ascending whip-like curved shoots. The bark is a pale grey and smooth when the individual is young. As the tree grows the bark becomes darker and cracks into slightly raised long plates.[7] The largest known living red maple is located near Armada, Michigan, at a height of 38.1 m (125 ft) and a bole circumference, at breast height, of 4.95 m (16 ft 3 in).[8]

The leaves of the red maple offer the easiest way to distinguish it from its relatives. As with all North American maple trees, they are deciduous and arranged oppositely on the twig. They are typically 5–10 cm (2–4 in) long and wide with three to five palmate lobes with a serrated margin. The sinuses are typically narrow, but the leaves can exhibit considerable variation.[6] When five lobes are present, the three at the terminal end are larger than the other two near the base. In contrast, the leaves of the related silver maple, A. saccharinum, are much more deeply lobed, more sharply toothed, and characteristically have five lobes. The upper side of A. rubrum's leaf is light green and the underside is whitish and can be either glaucous or hairy. The leaf stalks are usually red and are up to 10 cm (4 in) long. The leaves can turn a characteristic brilliant red in autumn, but can also become yellow or orange on some individuals. Soil acidity can influence the color of the foliage and trees with female flowers are more likely to produce orange coloration while male trees produce red. The fall colors of red maple are most spectacular in the northern part of its range where climates are cooler.

The twigs of the red maple are reddish in color and somewhat shiny with small lenticels. Dwarf shoots are present on many branches. The buds are usually blunt and greenish to reddish in color, generally with several loose scales. The lateral buds are slightly stalked, and in addition, collateral buds may be present, as well. The buds form in fall and winter and are often visible from a distance due to their large size and reddish tint. The leaf scars on the twig are V-shaped and contain three bundle scars.[6]

The flowers are generally unisexual, with male and female flowers appearing in separate sessile clusters, though they are sometimes also bisexual. They appear in late winter to early spring, from December[9] to May depending on elevation and latitude, usually before the leaves. The tree itself is considered polygamodioecious, meaning some individuals are male, some female, and some monoecious.[8] Under the proper conditions, the tree can sometimes switch from male to female, male to hermaphroditic, and hermaphroditic to female.[10] The red maple will begin blooming when it is about 8 years old, but it significantly varies between tree to tree: some trees may begin flowering when they are 4 years old. The flowers are red with 5 small petals and a 5-lobed calyx, usually at the twig tips. The staminate flowers are sessile. The pistillate flowers are borne on pedicels that grow out while the flowers are blooming, so that eventually the flowers are in a hanging cluster with stems 1 to 5 cm (1⁄2 to 2 in) long.[11] The petals are lineal to oblong in shape and are pubescent. The pistillate flowers have one pistil formed from two fused carpels with a glabrous superior ovary and two long styles that protrude beyond the perianth. The staminate flowers contain between 4 and 12 stamens, often with 8.[12]

The fruit is a schizocarp of 2 samaras, each one 15 to 25 mm (5⁄8 to 1 in) long. Prior to dehiscence, the wings of the fruit are somewhat divergent at an angle of 50 to 60°. They are borne on long slender pedicels and are variable in color from light brown to reddish.[6] They ripen from April through early June, before even the leaf development is altogether complete. After they reach maturity, the seeds are dispersed for a 1- to 2-week period from April through July.[8]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

Acer rubrum is one of the most abundant and widespread trees in eastern North America. It can be found from the south of Newfoundland, through Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and southern Quebec to the southwest west of Ontario, extreme southeastern Manitoba and northern Minnesota; southward through Wisconsin, Illinois, Missouri, eastern Oklahoma, and eastern Texas in its western range; and east to Florida. It has the largest continuous range along the North American Atlantic Coast of any tree that occurs in Florida. In total it ranges 2,600 km (1,600 mi) from north to south.[8] The species is native to all regions of the United States east of the 95th meridian. The tree's range ends where the −40 °C (−40 °F) mean minimum isotherm begins, namely in southeastern Canada. A. rubrum is not present in most of the Prairie Peninsula of the northern Midwest (although it is found in Ohio), the coastal prairie in southern Louisiana and southeastern Texas and the swamp prairie of the Florida Everglades.[8] Red maple's western range stops with the Great Plains where conditions become too dry for it. The absence of red maple from the Prairie Peninsula is most likely due to the tree's poor tolerance of wildfires. Red maple is most abundant in the Northeastern US, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and northeastern Wisconsin, and is rare in the extreme west of its range and in the Southeastern US.[8]

In several other locations, the tree is absent from large areas but still present in a few specific habitats. An example is the Bluegrass region of Kentucky, where red maple is not found in the dominant open plains, but is present along streams.[13] Here the red maple is not present in the bottom land forests of the Grain Belt, despite the fact it is common in similar habitats and species associations both to the north and south of this area. In the Northeastern US, red maple can be a climax forest species in certain locations, but will eventually give way to sugar maple.[8]

A. rubrum does very well in a wide range of soil types, with varying textures, moisture, pH, and elevation, probably more so than any other forest tree in North America. A. rubrum's wide pH tolerance means that it can grow in a variety of places, and it is widespread along the Eastern United States.[14] It grows on glaciated as well as unglaciated soils derived from granite, gneiss, schist, sandstone, shale, slate, conglomerate, quartzite, and limestone. Chlorosis can occur on very alkaline soils, though otherwise its pH tolerance is quite high. Moist mineral soil is best for germination of seeds.[8]

Red maple can grow in a variety of moist and dry biomes, from dry ridges and sunny, southwest-facing slopes to peat bogs and swamps. While many types of tree prefer a south- or north-facing aspect, the red maple does not appear to have a preference.[8] Its ideal conditions are in moderately well-drained, moist sites at low or intermediate elevations. However, it is nonetheless common in mountainous areas on relatively dry ridges, as well as on both the south and west sides of upper slopes. Furthermore, it is common in swampy areas, along the banks of slow moving streams, as well as on poorly drained flats and depressions. In northern Michigan and New England, the tree is found on the tops of ridges, sandy or rocky upland and otherwise dry soils, as well as in nearly pure stands on moist soils and the edges of swamps. In the far south of its range, it is almost exclusively associated with swamps.[8] Additionally, red maple is one of the most drought-tolerant species of maple in the Carolinas.[15]

Red maple is far more abundant today than when Europeans first arrived in North America. It only contributed minimally to old-growth upland forests, and would only form same-species stands in riparian zones.[8] The density of the tree in many of these areas has increased six- to seven-fold, and this trend seems to be continuing. One of the primary factors for this appears to be a loss of forest management that comes in several forms. First, a loss regular prescribed burns, such as those performed by Native Americans who would use the burns to enhance acorn and other seed harvesting.[16] Second, continued heavy logging and a recent trend of young, shrubby forests recovering from past human disturbances.[17] Third, the decline of American elm and American chestnut due to introduced diseases has contributed to its spread. Red maple dominates such sites, but largely disappears until it only has a sparse presence by the time a forest is mature. This species is in fact a vital part of forest regeneration in the same way that paper birch is.

Because it can grow on a variety of substrates, has a wide pH tolerance, and grows in both shade and sun, A. rubrum is a prolific seed producer and highly adaptable, often dominating disturbed sites. While many believe that it is replacing historically dominant tree species in the Eastern United States, such as sugar maples, beeches, oaks, hemlocks and pines, red maple will only dominate young forests prone to natural or human disturbance. In areas disturbed by humans where the species thrives, it can reduce diversity, but in a mature forest, it is not a dominant species; it only has a sparse presence and adds to the diversity and ecological structure of a forest. Extensive use of red maple in landscaping has also contributed to the surge in the species' numbers as volunteer seedlings proliferate. Finally, disease epidemics have greatly reduced the population of elms and chestnuts in the forests of the US. While mainline forest trees continue to dominate mesic sites with rich soil, more marginal areas are increasingly being dominated by red maple.[17]

Ecology

[edit]Red maple's maximum lifespan is 150 years, but most live less than 100 years. The tree's thin bark is easily damaged from ice and storms, animals, and when used in landscaping, being struck by flying debris from lawn mowers, allowing fungi to penetrate and cause heart rot.[8] Its ability to thrive in a large number of habitats is largely due to its ability to produce roots to suit its site from a young age. In wet locations, red maple seedlings produce short taproots with long, well-developed lateral roots; while on dry sites, they develop long taproots with significantly shorter laterals. The roots are primarily horizontal, however, forming in the upper 25 cm (9.8 in) of the ground. Mature trees have woody roots up to 25 m (82 ft) long. They are very tolerant of flooding, with one study showing that 60 days of flooding caused no leaf damage. At the same time, they are tolerant of drought due to their ability to stop growing under dry conditions by then producing a second-growth flush when conditions later improve, even if growth has stopped for 2 weeks.[8]

A. rubrum is one of the first plants to flower in spring. A crop of seeds is generally produced every year with a bumper crop often occurring every second year. A single tree between 5 and 20 cm (2.0 and 7.9 in) in diameter can produce between 12,000 and 91,000 seeds in a season. A tree 30 cm (0.98 ft) in diameter was shown to produce nearly a million seeds.[8] Red maple produces one of the smallest seeds of any of the maples.[15] Fertilization has also been shown to significantly increase the seed yield for up to two years after application.

The seeds are epigeal and tend to germinate in early summer soon after they are released, assuming a small amount of light, moisture, and sufficient temperatures are present. If the seeds are densely shaded, then germination commonly does not occur until the next spring. Most seedlings do not survive in closed forest canopy situations. However, one- to four-year-old seedlings are common under dense canopy. Though they eventually die if no light reaches them, they serve as a reservoir, waiting to fill any open area of the canopy above.

Trees growing in a Zone 9 or 10 area such as Florida will usually die from cold damage if transferred up north, for instance to Canada, Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire and New York, even if the southern trees were planted with northern red maples. Due to their wide range, genetically the trees have adapted to the climatic differences.

Red maple is able to increase its numbers significantly when associate trees are damaged by disease, cutting, or fire. One study found that 6 years after clearcutting a 3.4 hectares (8.4 acres) Oak-Hickory forest containing no red maples, the plot contained more than 2,200 red maple seedlings per hectare (900 per acre) taller than 1.4 m (4.6 ft).[8] One of its associates, the black cherry (Prunus serotina), contains benzoic acid, which has been shown to be a potential allelopathic inhibitor of red maple growth. Red maple is one of the first species to start stem elongation. In one study, stem elongation was one-half completed in 1 week, after which growth slowed and was 90% completed within only 54 days. In good light and moisture conditions, the seedlings can grow 30 cm (0.98 ft) in their first year and up to 60 cm (2.0 ft) each year for the next few years, making it a fast grower.[8]

The red maple is used as a food source by several forms of wildlife. Elk and white-tailed deer in particular use the current season's growth of red maple as an important source of winter food. Several Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) utilize the leaves as food, including larvae of the rosy maple moth (Dryocampa rubicunda); see List of Lepidoptera that feed on maples.

Due to A. rubrum's very wide range, there is significant variation in hardiness, size, form, time of flushing, onset of dormancy, and other traits. Generally speaking, individuals from the north flush the earliest, have the most reddish fall color, set their buds the earliest and take the least winter injury. Seedlings are tallest in the north-central and east-central part of the range. In Florida, at the extreme south of the red maple's range, it is limited exclusively to swamplands. The fruits also vary geographically with northern individuals in areas with brief, frost-free periods producing fruits that are shorter and heavier than their southern counterparts. As a result of such variation, there is much genetic potential for breeding programs with a goal of producing red maples for cultivation. This is especially useful for making urban cultivars that require resistance from verticillium wilt, air pollution, and drought.[8]

Red maple frequently hybridizes with silver maple; the hybrid, known as Freeman's maple, Acer × freemanii, is intermediate between the parents.

Allergenic potential

[edit]

The allergenic potential of red maples varies widely based on the cultivar.

The following cultivars are completely male and are highly allergenic, with an OPALS allergy scale rating of 8 or higher:[18]

- 'Autumn Flame' ('Flame')

- 'Autumn Spire'

- 'Columnare' ('Pyramidale')

- 'Firedance' ('Landsburg')

- 'Karpick'

- 'Northwood'

- 'October Brilliance'

- 'Sun Valley'

- 'Tiliford'

The following cultivars have an OPALS allergy scale rating of 3 or lower; they are completely female trees, and have low potential for causing allergies:[18]

- 'Autumn Glory'

- 'Bowhall'

- 'Davey Red'

- 'Doric'

- 'Embers'

- 'Festival'

- 'October Glory'

- 'Red Skin'

- 'Red Sunset' ('Franksred')

Toxicity

[edit]The leaves of red maple, especially when dead or wilted, are extremely toxic to horses. The toxin is unknown, but believed to be an oxidant because it damages red blood cells, causing acute oxidative hemolysis that inhibits the transport of oxygen. This not only decreases oxygen delivery to all tissues, but also leads to the production of methemoglobin, which can further damage the kidneys. The ingestion of 700 grams (1.5 pounds) of leaves is considered toxic and 1.4 kilograms (3 pounds) is lethal. Symptoms occur within one or two days after ingestion and can include depression, lethargy, increased rate and depth of breathing, increased heart rate, jaundice, dark brown urine, colic, laminitis, coma, and death. Treatment is limited and can include the use of methylene blue or mineral oil and activated carbon in order to stop further absorption of the toxin into the stomach, as well as blood transfusions, fluid support, diuretics, and anti-oxidants such as Vitamin C. About 50% to 75% of affected horses die or are euthanized as a result.[19]

Cultivation

[edit]

Red maple's rapid growth, ease of transplanting, attractive form, and value for wildlife (in the eastern US) has made it one of the most extensively planted trees. In parts of the Pacific Northwest, it is one of the most common introduced trees. Its popularity in cultivation stems from its vigorous habit, its attractive and early red flowers, and most importantly, its flaming red fall foliage. The tree was introduced into the United Kingdom in 1656 and shortly thereafter entered cultivation. There it is frequently found in many parks and yards.[7]

Red maple is a good choice of a tree for urban areas when there is ample room for its root system. Forming an association with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can help A. rubrum grow along city streets.[20] It is more tolerant of pollution and road salt than sugar maples, although the tree's fall foliage is not as vibrant in this environment. Like several other maples, its low root system can be invasive and it makes a poor choice for plantings near paving. It attracts squirrels, who eat its buds in the early spring, although squirrels prefer the larger buds of the silver maple.[21]

Red maples make vibrant and colorful bonsai, and have year around attractive features for display.[22]

Cultivars

[edit]Numerous cultivars have been selected, often for intensity of fall color, with 'October Glory' and 'Red Sunset' among the most popular. Toward its southern limit, 'Fireburst', 'Florida Flame', and 'Gulf Ember' are preferred. Many cultivars of the Freeman maple are also grown widely. Below is a partial list of cultivars:[23][24]

- 'Armstrong' – Columnar to fastigate in shape with silvery bark and modest orange to red fall foliage.

- 'Autumn Blaze' – Rounded oval form with leaves that resemble the silver maple. The fall color is orange red and persists longer than usual.

- 'Autumn Flame' – A fast grower with exceptional bright red fall color developing early. The leaves are also smaller than the species.

- 'Autumn Radiance' – Dense oval crown with an orange-red fall color.

- 'Autumn Spire' – Broad columnar crown; red fall color; very hardy.

- 'Bowhall' – Conical to upright in form with a yellow-red fall color.

- 'Burgundy Bell' – Compact rounded uniform shape with long lasting, burgundy fall leaves.

- 'Columnare' – An old cultivar growing to 20 metres (66 feet) with a narrow columnar to pyramidal form with dark green leaves turning orange and deep red in fall.

- 'Gerling' – A compact, slow growing selection, this individual only reaches 10 metres (33 feet) and has orange-red fall foliage.

- 'Northwood' – Branches are at a 45 degree angle to the trunk, forming a rounded oval crown. Though the foliage is deep green in summer, its orange-red fall color is not as impressive as other cultivars.

- 'October Brilliance' – This selection is slow to leaf in spring, but has a tight crown and deep red fall color.

- 'October Glory' – Has a rounded oval crown with late developing intense red fall foliage. Along with 'Red Sunset', it is the most popular selection due to the dependable fall color and vigorous growth. This cultivar has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[25]

- 'Redpointe' – Superior in alkaline soil, strong central leader, red fall color.

- 'Red Sunset' – is also a recipient of the Award of Garden Merit.[26] The other very popular choice, this selection does well in heat due to its drought tolerance and has an upright habit. It has very attractive orange-red fall color and is also a rapid and vigorous grower.

- 'Scarlet Sentinel' – A columnar to oval selection with 5-lobed leaves resembling the silver maple. The fall color is yellow-orange to orange-red and the tree is a fast grower.

- 'Schlesingeri' – A tree with a broad crown and early, long lasting fall color that is a deep red to reddish purple. Growth is also quite rapid. The original tree grew at the home of Barthold Schlesinger in Brookline, Massachusetts.[27]

- 'Shade King' – This fast growing cultivar has an upright-oval form with deep green summer leaves that turn red to orange in fall.

- 'V.J. Drake' – This selection is notable because the edges of the leaves first turn a deep red before the color progresses into the center.

Other uses

[edit]

In the lumber industry Acer rubrum is considered a "soft maple", a designation it shares, commercially, with silver maple (A. saccharinum). In this context, the term "soft" is more comparative, than descriptive; i.e., "soft maple", while softer than its harder cousin, sugar maple (A. saccharum), is still a fairly hard wood, being comparable to black cherry (Prunus serotina) in this regard. Like A. saccharum, the wood of red maple is close-grained, but its texture is softer, less dense, and has not as desirable an appearance, particularly under a clear finish. However, the wood from Acer rubrum while being typically less expensive than hard maple, also has greater dimensional stability than that of A. saccharum, and also machines and stains easier. Thus, high grades of wood from the red maple can be substituted for hard maple, particularly when it comes to making stain/paint-grade furniture. Red maple lumber also contains a greater percentage of "curly" (aka "flame"/"fiddleback") figure, which is prized by musical instrument/custom furniture makers, as well as the veneer industry. As a soft maple, the wood tends to shrink more during the drying process than with the hard maples.[28]

Red maple is also used for the production of maple syrup, though the hard maples Acer saccharum (sugar maple) and Acer nigrum (black maple) are more commonly utilized. One study compared the sap and syrup from the sugar maple with those of the red maple, as well as those of the Acer saccharinum (silver maple), Acer negundo (boxelder), and Acer platanoides (Norway maple), and all were found to be equal in sweetness, flavor, and quality. However, the buds of red maple and other soft maples emerge much earlier in the spring than the sugar maple, and after sprouting chemical makeup of the sap changes, imparting an undesirable flavor to the syrup. This being the case, red maple can only be tapped for syrup before the buds emerge, making the season very short.[8]

Native Americans used red maple bark as a wash for inflamed eyes and cataracts, and as a remedy for hives and muscular aches. They also would brew tea from the inner bark to treat coughs and diarrhea. Pioneers made cinnamon-brown and black dyes from a bark extract, and iron sulphate could be added to the tannin from red maple bark in order to make ink.[29]

Red maple is a medium quality firewood,[30] possessing less heat energy, nominally 5.4 gigajoules per cubic metre (18.7 million British thermal units per cord) , than other hardwoods such as ash: 7.0 GJ/m3 (24 million British thermal units per cord), oak: 7.0 GJ/m3 (24 million British thermal units per cord), or birch: 6.1 GJ/m3 (21 million British thermal units per cord).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Crowley, D.; Barstow, M. (2017). "Acer rubrum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017 e.T193860A2287111. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T193860A2287111.en. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ NatureServe (2 June 2023). "Acer rubrum". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Acer rubrum L.". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – via The Plant List. Note that this website has been superseded by World Flora Online

- ^ Nix, Steve. "Ten Most Common Trees in the United States". About.com Forestry. Archived from the original on 19 June 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Stevens, William K. (27 April 1999). "Eastern Forests Change Color As Red Maples Proliferate". New York Times. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d Seiler, John R.; Jensen, Edward C.; Peterson, John A. "Acer rubrum Fact Sheet". Virginia Tech Dendrology Tree Fact Sheets. Virginia Tech. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ a b Mitchell, A. F. (1974). Trees of Britain & Northern Europe. London: Harper Collins Publishers. p. 347. ISBN 0-00-219213-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Walters, R. S.; Yawney, H. W. (1990). "Acer rubrum". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 9 May 2007 – via Southern Research Station.

- ^ Gilman, Edward F.; Watson, Dennis G.; Klein, Ryan W.; Koeser, Andrew K.; Hilbert, Deborah R.; McLean, Drew C. "Acer rubrum: Red Maple" (PDF). Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Extension, University of Florida. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Primack, R.B.; McCall, C. (1986). "Gender Variation in Red Maple Populations (Acer rubrum; Aceraceae): A Seven-Year Study of a "Polygamodioecious" Species". American Journal of Botany. 73 (9): 1239–1248. doi:10.2307/2444057. JSTOR 2444057.

- ^ Hilty, John (2020). "Red Maple (Acer rubrum)". Illinois Wildflowers. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Goertz, D. "Acer rubrum plant description". Northern Ontario Plant Database. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- ^ Campbell, J. (1985). The Land of Cane and Clover: Pre-settlement Vegetation in the So-called Bluegrass Region of Kentucky (Report). Lexington: The Herbarium, University of Kentucky. p. 25. Unpublished manuscript.

- ^ DeForest, Jared L.; McCarthy, Brian C. (2011). "Diminished Soil Quality in an Old-Growth, Mixed Mesophytic Forest Following Chronic Acid Deposition Diminished Soil Quality in an Old-growth, Mixed Mesophytic Forest Following Chronic Acid Deposition". Northeastern Naturalist. 18 (2): 177–184. doi:10.1656/045.018.0204. S2CID 84557378.

- ^ a b Miller, J.H., & Miller, K.V. (1999). Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Champaign, IL: Kings Time Printing.

- ^ Oaster, Brian (21 October 2020). "Native land management could save us from wildfires, experts say". Street Roots. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ a b Abrams, Marc D. (May 1998). "The Red Maple Paradox". BioScience. 48 (5): 335–364. doi:10.2307/1313374. JSTOR 1313374.

- ^ a b Ogren, Thomas (2015). The Allergy-Fighting Garden. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-60774-491-7.

- ^ Goetz, R. J. "Red Maple Toxicity". Indiana Plants Poisonous to Livestock and Pets. Purdue University. Archived from the original on May 5, 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ Appleton, Bonnie; Koci, Joel (2003). "Mycorrhizal Fungal Inoculation of Established Street Trees". Journal of Arboriculture. 29 (2): 107–110.

- ^ Reichard, Timothy A. (October 1976). "Spring Food Habits and Feeding Behavior of Fox Squirrels and Red Squirrels". American Midland Naturalist. 96 (2): 443–450. doi:10.2307/2424082. JSTOR 2424082.

- ^ D'Cruz, Mark. "Acer Rubrum Bonsai Care Guide". Ma-Ke Bonsai. Archived from the original on 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ^ Evans, E. "Select Acer rubrum Cultivars". North Carolina State University.

- ^ Gilman, E. F.; Watson, Dennis G. "Acer rubrum 'Gerling'". University of Florida.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Acer rubrum 'October Glory' AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "Acer rubrum Red Sunset ('Franksred')". RHS. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Dosmann, Michael S. (2009). "Autumn's Harbinger: Acer rubrum 'Schlesingeri'". Arnoldia. 67 (2): 32–33. doi:10.5962/p.251053. Retrieved 6 June 2023 – via Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University.

- ^ "Red Maple (Acer rubrum)". GardenCenterPoint. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Nesom, Guy (24 May 2006). "Plant Guide: Red Maple, Acer rubrum L." (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Michael Kuhns and Tom Schmidt (n.d.). "Heating With Wood: Species Characteristics and Volumes". UtahState University Cooperative Extension. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2009-09-02.