Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

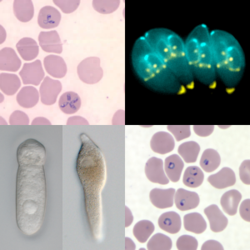

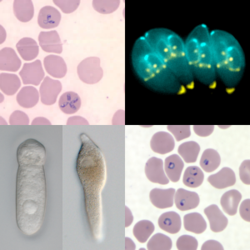

Apicomplexa

View on Wikipedia

| Apicomplexa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Sar |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Clade: | Myzozoa |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa Levine, 1970[1][2] |

| Classes and subclasses Perkins, 2000 | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Apicomplexa (also called Apicomplexia; single: apicomplexan) are organisms of a large phylum of mainly parasitic alveolates. Most possess a unique form of organelle structure that comprises a type of non-photosynthetic plastid called an apicoplast—with an apical complex membrane. The organelle's apical shape is an adaptation that the apicomplexan applies in penetrating a host cell.

The Apicomplexa are unicellular and spore-forming. Most are obligate endoparasites of animals,[3] except Nephromyces, a symbiont in marine animals, originally classified as a chytrid fungus,[4] and the Chromerida, some of which are photosynthetic partners of corals. Motile structures such as flagella or pseudopods are present only in certain gamete stages.

The Apicomplexa are a diverse group that includes organisms such as the coccidia, gregarines, piroplasms, haemogregarines, and plasmodia. Diseases caused by Apicomplexa include:

- Babesiosis (Babesia)

- Malaria (Plasmodium)

- Cryptosporidiosis (Cryptosporidium parvum)

- Cyclosporiasis (Cyclospora cayetanensis)

- Cystoisosporiasis (Cystoisospora belli)

- Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii)

The name Apicomplexa derives from two Latin words—apex (top) and complexus (infolds)—for the set of organelles in the sporozoite. The Apicomplexa comprise the bulk of what used to be called the Sporozoa, a group of parasitic protozoans, in general without flagella, cilia, or pseudopods. Most of the Apicomplexa can use gliding motility,[5] that uses adhesions and small static myosin motors.[6] The other main lines of this obsolete grouping were the Ascetosporea (a group of Rhizaria), the Myxozoa (highly derived cnidarian animals), and the Microsporidia (derived from fungi). Sometimes, the name Sporozoa is taken as a synonym for the Apicomplexa, or occasionally as a subset.

Description

[edit]

The phylum Apicomplexa contains all eukaryotes with a group of structures and organelles collectively termed the apical complex.[7] This complex consists of structural components and secretory organelles required for invasion of host cells during the parasitic stages of the Apicomplexan life cycle.[7] Apicomplexa have complex life cycles, involving several stages and typically undergoing both asexual and sexual replication.[7] All Apicomplexa are obligate parasites for some portion of their life cycle, with some parasitizing two separate hosts for their asexual and sexual stages.[7]

Besides the conserved apical complex, Apicomplexa are morphologically diverse. Different organisms within Apicomplexa, as well as different life stages for a given apicomplexan, can vary substantially in size, shape, and subcellular structure.[7] Like other eukaryotes, Apicomplexa have a nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex.[7] Apicomplexa generally have a single mitochondrion, as well as another endosymbiont-derived organelle called the apicoplast which maintains a separate 35 kilobase circular genome (with the exception of Cryptosporidium species and Gregarina niphandrodes which lack an apicoplast).[7]

All members of this phylum have an infectious stage—the sporozoite—which possesses three distinct structures in an apical complex. The apical complex consists of a set of spirally arranged microtubules (the conoid), a secretory body (the rhoptry) and one or more polar rings. Additional slender electron-dense secretory bodies (micronemes) surrounded by one or two polar rings may also be present. This structure gives the phylum its name. A further group of spherical organelles is distributed throughout the cell rather than being localized at the apical complex and are known as the dense granules. These typically have a mean diameter around 0.7 μm. Secretion of the dense-granule content takes place after parasite invasion and localization within the parasitophorous vacuole and persists for several minutes.[citation needed]

- Flagella are found only in the motile gamete. These are posteriorly directed and vary in number (usually one to three).

- Basal bodies are present. Although hemosporidians and piroplasmids have normal triplets of microtubules in their basal bodies, coccidians and gregarines have nine singlets.

- The mitochondria have tubular cristae.

- Centrioles, chloroplasts, ejectile organelles, and inclusions are absent.

- The cell is surrounded by a pellicle of three membrane layers (the alveolar structure) penetrated by micropores.

- Anterior polar ring

- Intra-conoid microtubules

- Conoid

- Posterior polar ring

- Inner membrane complex

- Subpellicular microtubules

- Rhoptries, hold enzymes released during host penetration

- Micronemes, important for host-cell invasion and gliding motility

- Mitochondrion, creates ATP (energy) for the cell (tubular cristae)

- Micropore

- Dense granules

- Apicoplast membranes (4, secondary red, non-photosynthetic)

- Golgi apparatus; modifies proteins and sends them out of the cell

- Nucleus

- Endoplasmic reticulum, the transport network for molecules going to specific parts of the cell

Replication:

- Mitosis is usually closed, with an intranuclear spindle; in some species, it is open at the poles.

- Cell division is usually by schizogony.

- Meiosis occurs in the zygote.

Mobility:

Apicomplexans have a unique gliding capability which enables them to cross through tissues and enter and leave their host cells. This gliding ability is made possible by the use of adhesions and small static myosin motors.[9]

Other features common to this phylum are a lack of cilia, sexual reproduction, use of micropores for feeding, and the production of oocysts containing sporozoites as the infective form.

Transposons appear to be rare in this phylum, but have been identified in the genera Ascogregarina and Eimeria.[10]

Life cycle

[edit]Most members have a complex lifecycle, involving both asexual and sexual reproduction. Typically, a host is infected via an active invasion by the parasites (similar to entosis), which divide to produce sporozoites that enter its cells. Eventually, the cells burst, releasing merozoites, which infect new cells. This may occur several times, until gamonts are produced, forming gametes that fuse to create new cysts. Many variations occur on this basic pattern, however, and many Apicomplexa have more than one host.[11]

The apical complex includes vesicles called rhoptries and micronemes, which open at the anterior of the cell. These secrete enzymes that allow the parasite to enter other cells. The tip is surrounded by a band of microtubules, called the polar ring, and among the Conoidasida is also a funnel of tubulin proteins called the conoid.[12] Over the rest of the cell, except for a diminished mouth called the micropore, the membrane is supported by vesicles called alveoli, forming a semirigid pellicle.[13]

The presence of alveoli and other traits place the Apicomplexa among a group called the alveolates. Several related flagellates, such as Perkinsus and Colpodella, have structures similar to the polar ring and were formerly included here, but most appear to be closer relatives of the dinoflagellates. They are probably similar to the common ancestor of the two groups.[13]

Another similarity is that many apicomplexan cells contain a single plastid, called the apicoplast, surrounded by either three or four membranes. Its functions are thought to include tasks such as lipid and heme biosynthesis, and it appears to be necessary for survival. In general, plastids are considered to have a common origin with the chloroplasts of dinoflagellates, and evidence points to an origin from red algae rather than green.[14][15]

Subgroups

[edit]Within this phylum are four groups — coccidians, gregarines, haemosporidians (or haematozoans, including in addition piroplasms), and marosporidians. The coccidians and haematozoans appear to be relatively closely related.[16]

Perkinsus , while once considered a member of the Apicomplexa, has been moved to a new phylum — Perkinsozoa.[17]

Gregarines

[edit]

The gregarines are generally parasites of annelids, arthropods, and molluscs. They are often found in the guts of their hosts, but may invade the other tissues. In the typical gregarine lifecycle, a trophozoite develops within a host cell into a schizont. This then divides into a number of merozoites by schizogony. The merozoites are released by lysing the host cell, which in turn invade other cells. At some point in the apicomplexan lifecycle, gametocytes are formed. These are released by lysis of the host cells, which group together. Each gametocyte forms multiple gametes. The gametes fuse with another to form oocysts. The oocysts leave the host to be taken up by a new host.[18]

Coccidians

[edit]

In general, coccidians are parasites of vertebrates. Like gregarines, they are commonly parasites of the epithelial cells of the gut, but may infect other tissues.

The coccidian lifecycle involves merogony, gametogony, and sporogony. While similar to that of the gregarines it differs in zygote formation. Some trophozoites enlarge and become macrogamete, whereas others divide repeatedly to form microgametes (anisogamy). The microgametes are motile and must reach the macrogamete to fertilize it. The fertilized macrogamete forms a zygote that in its turn forms an oocyst that is normally released from the body. Syzygy, when it occurs, involves markedly anisogamous gametes. The lifecycle is typically haploid, with the only diploid stage occurring in the zygote, which is normally short-lived.[19]

The main difference between the coccidians and the gregarines is in the gamonts. In the coccidia, these are small, intracellular, and without epimerites or mucrons. In the gregarines, these are large, extracellular, and possess epimerites or mucrons. A second difference between the coccidia and the gregarines also lies in the gamonts. In the coccidians, a single gamont becomes a macrogametocyte, whereas in the gregarines, the gamonts give rise to multiple gametocytes.[20]

Haemosporidia

[edit]

The Haemosporidia have more complex lifecycles that alternate between an arthropod and a vertebrate host. The trophozoite parasitises erythrocytes or other tissues in the vertebrate host. Microgametes and macrogametes are always found in the blood. The gametes are taken up by the insect vector during a blood meal. The microgametes migrate within the gut of the insect vector and fuse with the macrogametes. The fertilized macrogamete now becomes an ookinete, which penetrates the body of the vector. The ookinete then transforms into an oocyst and divides initially by meiosis and then by mitosis (haplontic lifecycle) to give rise to the sporozoites. The sporozoites escape from the oocyst and migrate within the body of the vector to the salivary glands where they are injected into the new vertebrate host when the insect vector feeds again.[21]

Marosporida

[edit]The class Marosporida Mathur, Kristmundsson, Gestal, Freeman, and Keeling 2020 is a newly recognized lineage of apicomplexans that is sister to the Coccidia and Hematozoa. It is defined as a phylogenetic clade containing Aggregata octopiana Frenzel 1885, Merocystis kathae Dakin, 1911 (both Aggregatidae, originally coccidians), Rhytidocystis sp. 1 and Rhytidocystis sp. 2 Janouškovec et al. 2019 (Rhytidocystidae Levine, 1979, originally coccidians, Agamococcidiorida), and Margolisiella islandica Kristmundsson et al. 2011 (closely related to Rhytidocystidae). Marosporida infect marine invertebrates. Members of this clade retain plastid genomes and the canonical apicomplexan plastid metabolism. However, marosporidians have the most reduced apicoplast genomes sequenced to date, lack canonical plastidial RNA polymerase and so provide new insights into reductive organelle evolution.[16]

Ecology and distribution

[edit]

Many of the apicomplexan parasites are important pathogens of humans and domestic animals. In contrast to bacterial pathogens, these apicomplexan parasites are eukaryotic and share many metabolic pathways with their animal hosts. This makes therapeutic target development extremely difficult – a drug that harms an apicomplexan parasite is also likely to harm its human host. At present, no effective vaccines are available for most diseases caused by these parasites. Biomedical research on these parasites is challenging because it is often difficult, if not impossible, to maintain live parasite cultures in the laboratory and to genetically manipulate these organisms. In recent years, several of the apicomplexan species have been selected for genome sequencing. The availability of genome sequences provides a new opportunity for scientists to learn more about the evolution and biochemical capacity of these parasites. The predominant source of this genomic information is the EuPathDB[22] family of websites, which currently provides specialised services for Plasmodium species (PlasmoDB),[23][24] coccidians (ToxoDB),[25][26] piroplasms (PiroplasmaDB),[27] and Cryptosporidium species (CryptoDB).[28][29] One possible target for drugs is the plastid, and in fact existing drugs such as tetracyclines, which are effective against apicomplexans, seem to operate against the plastid.[30]

Many Coccidiomorpha have an intermediate host, as well as a primary host, and the evolution of hosts proceeded in different ways and at different times in these groups. For some coccidiomorphs, the original host has become the intermediate host, whereas in others it has become the definitive host. In the genera Aggregata, Atoxoplasma, Cystoisospora, Schellackia, and Toxoplasma, the original is now definitive, whereas in Akiba, Babesiosoma, Babesia, Haemogregarina, Haemoproteus, Hepatozoon, Karyolysus, Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, Sarcocystis, and Theileria, the original hosts are now intermediate.

Similar strategies to increase the likelihood of transmission have evolved in multiple genera. Polyenergid oocysts and tissue cysts are found in representatives of the orders Protococcidiorida and Eimeriida. Hypnozoites are found in Karyolysus lacerate and most species of Plasmodium; transovarial transmission of parasites occurs in lifecycles of Karyolysus and Babesia.

Horizontal gene transfer appears to have occurred early on in this phylum's evolution with the transfer of a histone H4 lysine 20 (H4K20) modifier, KMT5A (Set8), from an animal host to the ancestor of apicomplexans.[31] A second gene—H3K36 methyltransferase (Ashr3 in plants)—may have also been horizontally transferred.[13]

Blood-borne genera

[edit]Within the Apicomplexa are three suborders of parasites:[13]

- suborder Adeleorina—eight genera

- suborder Laveraniina (formerly Haemosporina)—all genera in this suborder

- suborder Eimeriorina—two genera (Lankesterella and Schellackia)

Within the Adelorina are species that infect invertebrates and others that infect vertebrates. The Eimeriorina—the largest suborder in this phylum—the lifecycle involves both sexual and asexual stages. The asexual stages reproduce by schizogony. The male gametocyte produces a large number of gametes and the zygote gives rise to an oocyst, which is the infective stage. The majority are monoxenous (infect one host only), but a few are heteroxenous (lifecycle involves two or more hosts).

The number of families in this later suborder is debated, with the number of families being between one and 20 depending on the authority and the number of genera being between 19 and 25.

Taxonomy

[edit]History

[edit]The first Apicomplexa protozoan was seen by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who in 1674 saw probably oocysts of Eimeria stiedae in the gall bladder of a rabbit. The first species of the phylum to be described, Gregarina ovata, in earwigs' intestines, was named by Dufour in 1828. He thought that they were a peculiar group related to the trematodes, at that time included in Vermes.[32] Since then, many more have been identified and named. During 1826–1850, 41 species and six genera of Apicomplexa were named. In 1951–1975, 1873 new species and 83 new genera were added.[32]

The older taxon Sporozoa, included in Protozoa, was created by Leuckart in 1879[33] and adopted by Bütschli in 1880.[34] Through history, it grouped with the current Apicomplexa many unrelated groups. For example, Kudo (1954) included in the Sporozoa species of the Ascetosporea (Rhizaria), Microsporidia (Fungi), Myxozoa (Animalia), and Helicosporidium (Chlorophyta), while Zierdt (1978) included the genus Blastocystis (Stramenopiles).[35] Dermocystidium was also thought to be sporozoan. Not all of these groups had spores, but all were parasitic.[32] However, other parasitic or symbiotic unicellular organisms were included too in protozoan groups outside Sporozoa (Flagellata, Ciliophora and Sarcodina), if they had flagella (e.g., many Kinetoplastida, Retortamonadida, Diplomonadida, Trichomonadida, Hypermastigida), cilia (e.g., Balantidium) or pseudopods (e.g., Entamoeba, Acanthamoeba, Naegleria). If they had cell walls, they also could be included in plant kingdom between bacteria or yeasts.

Sporozoa is no longer regarded as biologically valid and its use is discouraged,[36] although some authors still use it as a synonym for the Apicomplexa. More recently, other groups were excluded from Apicomplexa, e.g., Perkinsus and Colpodella (now in Protalveolata).

The field of classifying Apicomplexa is in flux and classification has changed throughout the years since it was formally named in 1970.[1]

By 1987, a comprehensive survey of the phylum was completed: in all, 4516 species and 339 genera had been named. They consisted of:[37][32]

- Class Conoidasida

- Subclass Gregarinasina p.p.

- Order Eugregarinorida, with 1624 named species and 231 named genera

- Subclass Coccidiasina p.p

- Order Eucoccidiorida p.p

- Suborder Adeleorina p.p

- Group Hemogregarines, with 399 species and four genera

- Suborder Eimeriorina, with 1771 species and 43 genera

- Suborder Adeleorina p.p

- Order Eucoccidiorida p.p

- Subclass Gregarinasina p.p.

- Class Aconoidasida

- Order Haemospororida, with 444 species and nine genera

- Order Piroplasmorida, with 173 species and 20 genera

- Other minor groups omitted above, with 105 species and 32 genera

Although considerable revision of this phylum has been done (the order Haemosporidia now has 17 genera rather than 9), these numbers are probably still approximately correct.[38]

Jacques Euzéby (1988)

[edit]Jacques Euzéby in 1988[39] created a new class Haemosporidiasina by merging subclass Piroplasmasina and suborder Haemospororina.

- Subclass Gregarinasina (the gregarines)

- Subclass Coccidiasina

- Suborder Adeleorina (the adeleorins)

- Suborder Eimeriorina (the eimeriorins)

- Subclass Haemosporidiasina

- Order Achromatorida

- Order Chromatorida

The division into Achromatorida and Chromatorida, although proposed on morphological grounds, may have a biological basis, as the ability to store haemozoin appears to have evolved only once.[40]

Roberts and Janovy (1996)

[edit]Roberts and Janovy in 1996 divided the phylum into the following subclasses and suborders (omitting classes and orders):[41]

- Subclass Gregarinasina (the gregarines)

- Subclass Coccidiasina

- Suborder Adeleorina (the adeleorins)

- Suborder Eimeriorina (the eimeriorins)

- Suborder Haemospororina (the haemospororins)

- Subclass Piroplasmasina (the piroplasms)

These form the following five taxonomic groups:

- The gregarines are, in general, one-host parasites of invertebrates.

- The adeleorins are one-host parasites of invertebrates or vertebrates, or two-host parasites that alternately infect haematophagous (blood-feeding) invertebrates and the blood of vertebrates.

- The eimeriorins are a diverse group that includes one host species of invertebrates, two-host species of invertebrates, one-host species of vertebrates and two-host species of vertebrates. The eimeriorins are frequently called the coccidia. This term is often used to include the adeleorins.

- Haemospororins, often known as the malaria parasites, are two-host Apicomplexa that parasitize blood-feeding dipteran flies and the blood of various tetrapod vertebrates.

- Piroplasms where all the species included are two-host parasites infecting ticks and vertebrates.

Perkins (2000)

[edit]

Perkins et al. proposed the following scheme.[42] It is outdated as the Perkinsidae have since been recognised as a sister group to the dinoflagellates rather that the Apicomplexia:

- Class Aconoidasida

- Conoid present only in the ookinete of some species

- Order Haemospororida

- Macrogamete and microgamete develop separately. Syzygy does not occur. Ookinete has a conoid. Sporozoites have three walls. Heteroxenous: alternates between vertebrate host (in which merogony occurs) and invertebrate host (in which sporogony occurs). Usually blood parasites, transmitted by blood-sucking insects.

- Order Piroplasmorida

- Class Conoidasida

- Subclass Gregarinasina

- Order Archigregarinorida

- Order Eugregarinorida

- Suborder Adeleorina

- Suborder Eimeriorina

- Order Neogregarinorida

- Subclass Coccidiasina

- Order Agamococcidiorida

- Order Eucoccidiorida

- Order Ixorheorida

- Order Protococcidiorida

- Subclass Gregarinasina

- Class Perkinsasida

- Order Perkinsorida

- Family Perkinsidae

The name Protospiromonadida has been proposed for the common ancestor of the Gregarinomorpha and Coccidiomorpha.[43]

Another group of organisms that belong in this taxon are the corallicolids.[44] These are found in coral reef gastric cavities. Their relationship to the others in this phylum has yet to be established.

Another genus has been identified - Nephromyces - which appears to be a sister taxon to the Hematozoa.[45] This genus is found in the renal sac of molgulid ascidian tunicates.

Evolution

[edit]Members of this phylum, except for the photosynthetic chromerids,[46] are parasitic and evolved from a free-living ancestor. This lifestyle is presumed to have evolved at the time of the divergence of dinoflagellates and apicomplexans.[47][48] Further evolution of this phylum has been estimated to have occurred about 800 million years ago.[49] The oldest extant clade is thought to be the archigregarines.[47]

These phylogenetic relations have rarely been studied at the subclass level. The Haemosporidia are related to the gregarines, and the piroplasms and coccidians are sister groups.[50] The Haemosporidia and the Piroplasma appear to be sister clades, and are more closely related to the coccidians than to the gregarines.[10] Marosporida is a sister group to Coccidiomorphea.[16]

| Myzozoa |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Janouškovec et al. 2015 presents a somewhat different phylogeny, supporting the work of others showing multiple events of plastids losing photosynthesis. More importantly this work provides the first phylogenetic evidence that there have also been multiple events of plastids becoming genome-free.[51]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Levine ND (1970). "Taxonomy of the Sporozoa". J Parasitol. 56 (4, Sect. 2, Part 1: Supplement: Proceedings Of the Second International Congress of Parasitology): 208–9. JSTOR 3277701.

- ^ Levine ND (May 1971). "Uniform Terminology for the Protozoan Subphylum Apicomplexa". J Eukaryot Microbiol. 18 (2): 352–5. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1971.tb03330.x.

- ^ Jadwiga Grabda (1991). Marine fish parasitology: an outline. VCH. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-89573-823-3.

- ^ Saffo M. B.; McCoy A. M.; Rieken C.; Slamovits C. H. (2010). "Nephromyces, a beneficial apicomplexan symbiont in marine animals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (37): 16190–5. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716190S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1002335107. PMC 2941302. PMID 20736348.

- ^ Kappe, Stefan H.I.; et al. (January 2004). "Apicomplexan gliding motility and host cell invasion: overhauling the motor model". Trends in Parasitology. 20 (1): 13–16. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.458.5746. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2003.10.011. PMID 14700584.

- ^ Sibley, L.D.I. (Oct 2010). "How apicomplexan parasites move in and out of cells". Curr Opin Biotechnol. 21 (5): 592–598. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2010.05.009. PMC 2947570. PMID 20580218.

- ^ a b c d e f g Slapeta J, Morin-Adeline V (2011). "Apicomplexa, Levine 1970". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Patrick J. Keeling; Yana Eglit (21 November 2023). "Openly available illustrations as tools to describe eukaryotic microbial diversity". PLOS Biology. 21 (11) e3002395. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PBIO.3002395. ISSN 1544-9173. PMC 10662721. PMID 37988341.

- ^ Sibley, L. D. (2004-04-09). "Intracellular Parasite Invasion Strategies". Science. 304 (5668): 248–253. Bibcode:2004Sci...304..248S. doi:10.1126/science.1094717. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15073368. S2CID 23218754.

- ^ a b Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, Chen WJ, et al. (February 2010). "A genome-sequence survey for Ascogregarina taiwanensis supports evolutionary affiliation but metabolic diversity between a Gregarine and Cryptosporidium". Mol. Biol. Evol. 27 (2): 235–48. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp226. PMC 2877549. PMID 19778951.

- ^ Templeton, Thomas J.; Iyer, Lakshminarayan M.; Anantharaman, Vivek; Enomoto, Shinichiro; Abrahante, Juan E.; Subramanian, G.M.; Hoffman, Stephen L.; Abrahamsen, Mitchell S.; Aravind, L. (September 2004). "Comparative Analysis of Apicomplexa and Genomic Diversity in Eukaryotes". Genome Research. 14 (9): 1686–1695. doi:10.1101/gr.2615304. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 515313. PMID 15342554.

- ^ Duszynski, Donald W.; Upton, Steve J.; Couch, Lee (2004-02-21). "The Coccidia of the World". Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, and Division of Biology, Kansas State University. Archived from the original (Online database) on 2010-12-30. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ^ a b c d Angel., Sherman (2018). Medical Parasitology. EDTECH. ISBN 978-1-83947-353-1. OCLC 1132400230.

- ^ Patrick J. Keeling (2004). "Diversity and evolutionary history of plastids and their hosts". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1481–1493. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1481. PMID 21652304.

- ^ Ram, Ev; Naik, R; Ganguli, M; Habib, S (July 2008). "DNA organization by the apicoplast-targeted bacterial histone-like protein of Plasmodium falciparum". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (15): 5061–73. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn483. PMC 2528193. PMID 18663012.

- ^ a b c Mathur, Varsha; Kwong, Waldan K.; Husnik, Filip; Irwin, Nicholas A. T.; Kristmundsson, Árni; Gestal, Camino; Freeman, Mark; Keeling, Patrick J (18 November 2020). "Phylogenomics Identifies a New Major Subgroup of Apicomplexans, Marosporida class nov., with Extreme Apicoplast Genome Reduction". Genome Biology and Evolution. 13 (2: evaa244) evaa244. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gbe/evaa244. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 7875001. PMID 33566096.

- ^ Norén, Fredrik; Moestrup, Øjvind; Rehnstam-Holm, Ann-Sofi (October 1999). "Parvilucifera infectans norén et moestrup gen. et sp. nov. (perkinsozoa phylum nov.): a parasitic flagellate capable of killing toxic microalgae". European Journal of Protistology. 35 (3): 233–254. doi:10.1016/S0932-4739(99)80001-7.

- ^ Wong, Wesley; Wenger, Edward A.; Hartl, Daniel L.; Wirth, Dyann F. (2018-01-09). "Modeling the genetic relatedness of Plasmodium falciparum parasites following meiotic recombination and cotransmission". PLOS Computational Biology. 14 (1) e1005923. Bibcode:2018PLSCB..14E5923W. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005923. ISSN 1553-7358. PMC 5777656. PMID 29315306.

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W.; Burki, Fabien; Cárdenas, Paco; Čepička, Ivan; Chistyakova, Lyudmila; Campo, Javier; Dunthorn, Micah (2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. ISSN 1066-5234. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Cruz-Bustos, Teresa; Feix, Anna Sophia; Ruttkowski, Bärbel; Joachim, Anja (2021-10-04). "Sexual Development in Non-Human Parasitic Apicomplexa: Just Biology or Targets for Control?". Animals. 11 (10): 2891. doi:10.3390/ani11102891. ISSN 2076-2615. PMC 8532714. PMID 34679913.

- ^ Frischknecht, Friedrich; Matuschewski, Kai (2017-01-20). "Plasmodium Sporozoite Biology". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 7 (5) a025478. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a025478. ISSN 2157-1422. PMC 5411682. PMID 28108531.

- ^ "EuPathDB". Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ Bahl, A.; Brunk, B.; Crabtree, J.; Fraunholz, M. J.; Gajria, B.; Grant, G. R.; Ginsburg, H.; Gupta, D.; Kissinger, J. C.; Labo, P.; Li, L.; Mailman, M. D.; Milgram, A. J.; Pearson, D. S.; Roos, D. S.; Schug, J.; Stoeckert Jr, C. J.; Whetzel, P. (2003). "PlasmoDB: The Plasmodium genome resource. A database integrating experimental and computational data". Nucleic Acids Research. 31 (1): 212–215. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg081. PMC 165528. PMID 12519984.

- ^ "PlasmoDB". Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ Kissinger, J. C.; Gajria, B.; Li, L.; Paulsen, I. T.; Roos, D. S. (2003). "ToxoDB: Accessing the Toxoplasma gondii genome". Nucleic Acids Research. 31 (1): 234–236. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg072. PMC 165519. PMID 12519989.

- ^ "ToxoDB". Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ "PiroplasmaDB". Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ Heiges, M.; Wang, H.; Robinson, E.; Aurrecoechea, C.; Gao, X.; Kaluskar, N.; Rhodes, P.; Wang, S.; He, C. Z.; Su, Y.; Miller, J.; Kraemer, E.; Kissinger, J. C. (2006). "CryptoDB: A Cryptosporidium bioinformatics resource update". Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (90001): D419 – D422. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj078. PMC 1347441. PMID 16381902.

- ^ "CryptoDB". Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ Dahl, El; Shock, Jl; Shenai, Br; Gut, J; Derisi, Jl; Rosenthal, Pj (September 2006). "Tetracyclines specifically target the apicoplast of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 50 (9): 3124–31. doi:10.1128/AAC.00394-06. PMC 1563505. PMID 16940111.

- ^ Kishore SP, Stiller JW, Deitsch KW (2013). "Horizontal gene transfer of epigenetic machinery and evolution of parasitism in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum and other apicomplexans". BMC Evol. Biol. 13 (1) 37. Bibcode:2013BMCEE..13...37K. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-37. PMC 3598677. PMID 23398820.

- ^ a b c d Levine N. D. (1988). "Progress in taxonomy of the Apicomplexan protozoa". The Journal of Protozoology. 35 (4): 518–520. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1988.tb04141.x. PMID 3143826.

- ^ Leuckart, R. (1879). Die menschlichen Parasiten. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Leipzig: Winter.

- ^ Bütschli, O. (1880-82). Dr. H.G. Bronn's Klassen und Ordnungen des Thier-Reichs. Erster Band: Protozoa. Abt. I, Sarkodina und Sporozoa, [1].

- ^ Perez-Cordon, G.; et al. (2007). "Finding of Blastocystis sp. in bivalves of the genus Donax". Rev. Peru. Biol. 14 (2): 301–2. doi:10.15381/rpb.v14i2.1824.

- ^ "Introduction to the Apicomplexa". Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ Levine, N.D. (1988). The protozoan phylum Apicomplexa. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4653-8.

- ^ Karadjian, Gregory; Hassanin, Alexandre; Saintpierre, Benjamin; Gembu Tungaluna, Guy-Crispin; Ariey, Frederic; Ayala, Francisco J.; Landau, Irene; Duval, Linda (2016-08-15). "Highly rearranged mitochondrial genome in Nycteria parasites (Haemosporidia) from bats". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (35): 9834–9839. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.9834K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1610643113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5024609. PMID 27528689.

- ^ Euzéby, J. (1988). Apicomplexa, 2: Hémosporidioses, Fascicule 1: Plasmodiidés, Haemoproteidés "Piroplasmes" (caractères généraux). Protozoologie Médicale Comparée. Vol. 3. Fondation Marcel Merieux. ISBN 978-2-901773-73-3. OCLC 463445910.

- ^ Martinsen ES, Perkins SL, Schall JJ (April 2008). "A three-genome phylogeny of malaria parasites (Plasmodium and closely related genera): evolution of life-history traits and host switches". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 47 (1): 261–73. Bibcode:2008MolPE..47..261M. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.11.012. PMID 18248741.

- ^ Roberts, L.; Janovy, J. (1996). Foundations of Parasitology (5th ed.). Dubuque IA: Wm. C. Brown. ISBN 978-0-697-26071-0. OCLC 33439613.

- ^ Perkins FO, Barta JR, Clopton RE, Peirce MA, Upton SJ (2000). "Phylum Apicomplexa". In Lee JJ, Leedale GF, Bradbury P (eds.). An Illustrated guide to the Protozoa: organisms traditionally referred to as protozoa, or newly discovered groups. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Society of Protozoologists. pp. 190–369. ISBN 978-1-891276-22-4. OCLC 704052757.

- ^ Krylov MV (1992). "[The origin of heteroxeny in Sporozoa]". Parazitologiia (in Russian). 26 (5): 361–368. PMID 1297964.

- ^ Kwong, WK; Del Campo, J; Mathur, V; Vermeij, MJA; Keeling, PJ (2019). "A widespread coral-infecting apicomplexan with chlorophyll biosynthesis genes". Nature. 568 (7750): 103–107. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..103K. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1072-z. PMID 30944491. S2CID 92996418.

- ^ Muñoz-Gómez SA, Durnin K, Eme L, Paight C, Lane CE, Saffo MB, Slamovits CH (2019) Nephromyces represents a diverse and novel lineage of the Apicomplexa that has retained apicoplasts. Genome Biol Evol

- ^ Moore RB; Oborník M; Janouskovec J; Chrudimský T; Vancová M; Green DH; Wright SW; Davies NW; et al. (February 2008). "A photosynthetic alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites". Nature. 451 (7181): 959–963. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..959M. doi:10.1038/nature06635. PMID 18288187. S2CID 28005870.

- ^ a b Kuvardina ON, Leander BS, Aleshin VV, Myl'nikov AP, Keeling PJ, Simdyanov TG (November 2002). "The phylogeny of colpodellids (Alveolata) using small subunit rRNA gene sequences suggests they are the free-living sister group to apicomplexans". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 49 (6): 498–504. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2002.tb00235.x. PMID 12503687. S2CID 4283969.

- ^ Leander BS, Keeling PJ (August 2003). "Morphostasis in alveolate evolution". Trends Ecol Evol. 18 (8): 395–402. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.410.9134. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00152-6.

- ^ Escalante AA, Ayala FJ (June 1995). "Evolutionary origin of Plasmodium and other Apicomplexa based on rRNA genes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (13): 5793–7. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.5793E. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.13.5793. PMC 41587. PMID 7597031.

- ^ Morrison DA (August 2009). "Evolution of the Apicomplexa: where are we now?". Trends Parasitol. 25 (8): 375–82. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2009.05.010. PMID 19635681.

- ^ Smith, David Roy; Keeling, Patrick J. (2016-09-08). "Protists and the Wild, Wild West of Gene Expression: New Frontiers, Lawlessness, and Misfits". Annual Review of Microbiology. 70 (1). Annual Reviews: 161–178. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095448. ISSN 0066-4227. PMID 27359218.

External links

[edit]- Brands, S.J. (2000). "The Taxonomicon & Systema Naturae". Taxon: Genus Cryptosporidium. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Universal Taxonomic Services. Archived from the original (Website database) on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2006-10-13.

- "David Roos's Seminar: Biology of Apicomplexan Parasites".