Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Riot grrrl

View on Wikipedia

| Riot grrrl | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Early 1990s, Pacific Northwest and Olympia, Washington, US |

| Typical instruments |

|

| Regional scenes | |

| Washington | |

| Local scenes | |

| Olympia, Washington, US | |

| Other topics | |

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

Riot grrrl is an underground feminist punk movement that began during the early 1990s within the United States in Olympia, Washington,[1][2] and the greater Pacific Northwest,[3] and has expanded to at least 26 other countries.[4] A subcultural movement that combines feminism, punk music, and politics,[5] it is often associated with third-wave feminism, which is sometimes seen as having grown out of the riot grrrl movement and has recently been seen in fourth-wave feminist punk music that rose in the 2010s.[6] It has also been described as a genre that came out of indie rock, with the punk scene serving as an inspiration for a movement in which women could express anger, rage, and frustration, emotions considered socially acceptable for male songwriters but less commonly for women.[7]

Riot grrrl songs often address issues such as rape, domestic abuse, sexuality, racism, patriarchy, classism, anarchism, and female empowerment. Primary bands most associated with the movement by media include Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy, Excuse 17, Slant 6, Emily's Sassy Lime, Huggy Bear, Jack Off Jill and Skinned Teen.[1][3][8][9][10][11][12][13] Also included are queercore groups such as Team Dresch and the Third Sex.[1][14]

In addition to a unique music scene and genre, riot grrrl became a subculture involving a DIY ethic, zines, art, political action, and activism.[15] The movement quickly spread well beyond its musical roots to influence the vibrant zine- and Internet-based nature of fourth-wave feminism, complete with local meetings and grassroots organizing to end intersectional forms of prejudice and oppression, especially physical and emotional violence against all genders.[16]

Origins

[edit]The riot grrrl movement originated in 1991, when a group of women from Olympia, Washington, and Washington, D.C., held a meeting about sexism in their local punk scenes in the United States.[17] The word "girl" was intentionally used in order to focus on childhood, a time when children have the strongest self-esteem and belief in themselves.[18] Riot grrrls then took a growling "R", replacing the "I" in the word as a way to take back the derogatory use of the term.[19] Both double and triple "R" spellings are acceptable.[20]

The Seattle and Olympia, Washington, music scenes in the Pacific Northwest had sophisticated do it yourself (DIY) infrastructure.[21] Women involved in local underground music scenes took advantage of this platform to articulate their feminist beliefs and desires by creating zines.[22] While the model of politically themed zines had already been used in punk culture as an alternative (to mainstream) culture, zines also followed a longer legacy of self-published feminist writing that allowed women to circulate ideas that would not otherwise be published.[22] At the time there was discomfort among many women in the music scene who felt that they had no space for organizing due to the exclusionary, male-dominated nature of punk culture at the time. Many women found that while they identified with the larger, music-oriented subculture of punk rock, they often had little to no voice in their local scenes. Women in the Washington punk scenes took it upon themselves to represent their own interests artistically through the new riot grrrl subculture.[23] To quote Liz Naylor, who would become the manager of English riot grrrl band Huggy Bear:[21]

There was a lot of anger and self-mutilation. In a symbolic sense, women were cutting and destroying the established image of femininity, aggressively tearing it down.

Riot grrrl bands were influenced by groundbreaking female punk and mainstream rock performers of the 1970s to the mid-1980s. While many of these musicians were not originally associated with each other during their time and came from a variety of backgrounds and styles, as a group they anticipated many of riot grrrl's musical and thematic attributes. These performers include the Slits, Poly Styrene, Siouxsie Sioux, the Raincoats, Joan Jett, Kim Gordon, and Kim Deal, among others.[21][9][10][17][24][25][26][27][28][29] Of Kim Gordon, in particular, Kathleen Hanna noted, "She was a forerunner, musically [...] Just knowing a woman was in a band trading lead vocals, playing bass, and being a visual artist at the same time made me feel less alone."[29] Riot grrrl musicians and musicians-to-be were also inspired by the 1982 U.S. musical drama movie Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains, which tells the story of a (fictional) seemingly proto-riot grrrl band.[30]

Pacific Northwest and Washington, D.C.

[edit]Olympia, Washington, had a strong feminist artistic and cultural legacy that influenced early riot grrrl. In the early 1980s, Stella Marrs, Dana Squires and Julie Fay co-founded the store Girl City, where they created art and performances.[31] The first K Records release in 1982 was a cassette of Heather Lewis' first band Supreme Cool Beings, while she was a student at The Evergreen State College, a year before she co-founded Beat Happening.[32] In 1985, the Go Team formed with then 15-year-old Tobi Vail. The band would go on to collaborate with Olympia scene musicians who are linked to the riot grrrl movement: Donna Dresch, Lois Maffeo, and Billy "Boredom" Karren.[11][33] Karren was a rotating musician who played in the band, and it was there that he and Vail played together for the first time, later collaborating in several other bands which included Bikini Kill and the Frumpies. Maffeo hosted a women-centered radio show on Olympia's community radio station KAOS.[31][34][35] Candice Pedersen interned at K Records in 1986 while at The Evergreen State College, and became co-owner in 1989.[31][36][37]

In the 1980s, two articles on the topic of women in rock would be published by Puncture, a Portland, Oregon, zine edited by Katherine Spielmann and Patty Stirling.[38] Authored by Rough Trade employee Terri Sutton, these articles became what is considered by some to be groundbreaking and influential writing on riot grrrl ethos.[39] One article, "Women, Sex, & Rock 'n' Roll" (1989) is considered particularly important as the manifesto of the riot grrrl movement.[40] Sutton would also say, in "Women In Rock: An Open Letter", written in 1988, "To me rock and roll is about lust, lust for feeling; the worst I can say about a band is they're boring. That's why it's so crucial that women get up onstage and impart--inspire some emotion."[41]

Meanwhile in the Washington, D.C., area, Beat Happening fan Erin Smith started her zine Teenage Gang Debs in 1987.[42] In 1988, two D.C. women that had been in all-women punk bands there previously – Chalk Circle's Sharon Cheslow and Fire Party's Amy Pickering – joined forces with Cynthia Connolly and Lydia Ely to organize group discussions focusing on gender differences and sexism in the D.C. punk community.[35][43] The results were published in the June 1988 issue of Maximum Rock 'n' Roll.[43] In November 1988, Connolly published the book Banned in DC: Photos and Anecdotes From the DC Punk Underground (79–85) through her small press Sun Dog Propaganda, and it was co-edited with Cheslow and Ely along with Leslie Clague.[35][42][44] These conversations and the book laid the groundwork for riot grrrl when members of Bikini Kill and Bratmobile later came to D.C. in 1991.[43] In fall 1989, Erin Smith visited Olympia and met Maffeo through Beat Happening's Calvin Johnson.[42] Johnson had been in the Go Team with Vail, and co-owned K Records with Candice Pedersen. At the end of 1989, Cheslow began publishing her zine Interrobang?! focusing on punk and sexism, and the first issue included an interview with Nation of Ulysses (NOU).[42] Vail saw a copy of this issue and was instantly captivated by NOU's aesthetic.[43]

Vail began publishing her zine Jigsaw in 1988, around the same time that Dresch started her zine Chainsaw.[42] Zines became a means of urgent expression; Laura Sister Nobody wrote in her zine Sister Nobody, "Us, we are women who know that something is happening – something that seems like a secret right now, but won't stay like a secret for much longer."[35] At the time, Vail was working at a sandwich shop with Kathi Wilcox who was impressed by Vail's interest in "girls in bands, specifically," including an aggressive emphasis on feminist issues.[45] Meanwhile, in 1989 Kathleen Hanna had co-founded the Olympia art collective/band Amy Carter and feminist gallery/music venue Reko Muse, both with Tammy Rae Carland and Heidi Arbogast.[34] By summer 1989, the space had hosted the Go Team, Babes in Toyland, and Nirvana.[34] Hanna also interned at SafePlace, an Olympia domestic violence shelter and provider of sexual assault/abuse services, for which she did counseling, gave presentations at local high schools, and started a discussion group for teenage girls.[34] Hanna came upon a copy of Jigsaw in 1989 and found resonance with Vail's writing.[42][46] Hanna began to contribute to the zine, submitting interviews to Jigsaw while on tour with Viva Knieval in 1990.[42][47] In Jigsaw, Vail wrote about "angry grrls", combining the word girls with a powerful growl.[22] Some issues of Jigsaw have been archived at Harvard University as a research resource along with other counterculture zines.[48] After touring for two months in summer 1990, Hanna's band Viva Knievel called it quits.[47] Hanna then began collaborating with Vail after attending a performance of the Go Team and recognizing Vail as the mastermind behind Jigsaw zine.[49] Dresch later started a record label under the name Chainsaw and formed the queercore band Team Dresch. In Chainsaw #2 she wrote, "Right now, maybe, Chainsaw is about Frustration. Frustration in music. Frustration in living, in being a girl, in being a homo, in being a misfit of any sort...Which is where this whole punk rock thing came from in the first place."[35]

Molly Neuman (from D.C.) and Allison Wolfe (from Olympia) met in fall 1989 while living next door to each other in dorms at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon, and they traveled to Olympia on weekends.[42][50] They first read Vail's zine Jigsaw in January 1990, and around the same time met Hanna.[50] While on winter break 1990–91, Neuman returned to Washington, D.C., where her family lived and created the first issue of the zine Girl Germs.[37][42][50] Corin Tucker came up with the band name Heavens to Betsy in Eugene during the summer of 1990, and moved to Olympia that fall to attend The Evergreen State College.[42][51] Kathleen Hanna and her friends Tobi Vail and Kathi Wilcox, who were also studying at Evergreen, recruited Billy Karren to form Bikini Kill in fall 1990.[42] Neuman and Wolfe played their first show on Valentine's Day 1991 at the North Shore Surf Club in Olympia, after Johnson invited them to perform on a bill with Bikini Kill and Some Velvet Sidewalk.[42][50] While working on a documentary film about the Olympia music scene, Tucker went to this show and interviewed Neuman and Wolfe.[50] Hanna, Vail and Wilcox collaborated on a feminist zine titled Bikini Kill for their first tours in 1991.[49][52] The Riot Grrrl movement believed in girls actively engaging in cultural production, creating their own music and fanzines rather than following existing materials. The bands associated with Riot Grrrl used their music to express feminist and anti-racist viewpoints. Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Heavens to Betsy created songs with extremely personal lyrics that dealt with topics such as rape, incest and eating disorders.[53][54]

Jenny Toomey and Hanna had known each other as young teens while attending the same D.C. area junior high school.[55] Toomey co-founded the indie rock label Simple Machines with Kristin Thomson in early 1990, and they ran the label out of a punk group house in Arlington, Virginia. They shared the house with Positive Force activists before moving into their own group house in Arlington.[56] Toomey visited Olympia during fall 1990, where she formed My New Boyfriend with Tobi Vail, Aaron Stauffer from Seaweed, and Christina Calle.[57] Upon returning to Arlington, Toomey and Thomson formed the indie rock band Tsunami.

The third issue of Vail's zine Jigsaw, published in 1991 after she spent time in Washington, D.C., was subtitled "angry grrrl zine".[42] In spring 1991 Cheslow was living in San Francisco, and she received letters from Ian MacKaye and Nation of Ulysses' Tim Green informing her about Bikini Kill and "angry grrrl" zines.[42] That spring 1991, Neuman and Wolfe spent spring break in D.C. and formed Bratmobile there with Erin Smith, Christina Billotte (of Autoclave), and Jen Smith.[42] Bikini Kill toured with Nation of Ulysses in May/June 1991, converging in D.C. with Bratmobile that summer.[35][42] It was here that Neuman and Wolfe created the first issue of riot grrrl zine.[35]

While Bikini Kill and Bratmobile band members were in D.C. during summer 1991, a meeting was held with women from the D.C. area to discuss how to address sexism in the punk scene. These women were inspired by recent anti-racist riots in D.C., and they wanted to start a "girl riot" against a society they felt offered no validation of women's experiences.[17] The first riot grrrl meeting was organized by Kathleen Hanna and Jenny Toomey, and it was held at the Positive Force group house in Arlington, Virginia.[56][58] Hanna later said, "We had to go to a Positive Force meeting first. I'd never had a pitch meeting before. But I was doing a pitch meeting for why they should let us use their house for this all-women's radical feminist community organizing meeting."[56]

In August 1991 many of these individuals gathered at the International Pop Underground Convention in Olympia. The first night of the event became known as "Girl Night".[59] Tucker played her first show that night, on guitar and vocals with Heavens to Betsy and Tracy Sawyer on drums.[51][59] Writing later about that summer, Melissa Klein (Wolfe's housemate at the time) said, "Young women's anger and questioning fomented and smoldered until it became an all-out gathering of momentum toward action...Bikini Kill promoted 'Revolution Girl Style Now' and 'Stop the J-Word Jealousy From Killing Girl Love'."[35] As this ideal spread via band tours, zines, and word of mouth, riot grrrl chapters sprang up around the country.[35]

Bikini Kill

[edit]Kathleen Hanna, Tobi Vail, and Kathi Wilcox were all studying at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington during the late 1980s. Hanna worked at Reko Muse, a small collective art gallery that would frequently host local bands to play shows between art exhibitions. There she met Vail after booking her band, the Go Team.[60] At the same time, Vail was writing Jigsaw zine and working with friend Wilcox. Vail wrote at the time in Jigsaw:

I feel completely left out of the realm of everything that is so important to me. And I know that this is partly because punk rock is for and by boys mostly and partly because punk rock of this generation is coming of age in a time of mindless career-goal bands.[61]

With Billy Karren, Bikini Kill self-released a cassette of demos during summer 1991 titled Revolution Girl Style Now. Hanna, Vail and Wilcox also began collaboration on Bikini Kill zine during their first tours in 1991.[49][52] The band wrote songs collaboratively and encouraged a female-centric environment at their shows, urging women to come to the front of the stage and handing out lyric sheets. Bikini Kill made it their goal to inspire more women to join the male-dominated punk scene.[62] Hanna would also stage dive into the crowds to personally remove male hecklers who would often verbally and physically assault her during shows.[63] However, the band's reach did include a large male audience in addition to the female target audience.[63]

After releasing the Bikini Kill EP on the indie label Kill Rock Stars in 1992, Bikini Kill began to establish their audience. Members of Bikini Kill also began to collaborate with other high-profile musicians, including Joan Jett, whose music Hanna has described as an early example of the riot grrrl aesthetic.[64] Jett produced the single "New Radio"/"Rebel Girl" for the band after members of Bikini Kill heard "Activity Grrrl", a song Jett wrote about the band.[65] Bikini Kill's debut album Pussy Whipped, released in 1993, included the song "Rebel Girl". "Rebel Girl" has become one of Bikini Kill's signature songs as well as a widely recognized anthem for the riot grrrl movement[66][67] While "the unforgettable anthem", as Robert Christgau calls it,[68] never charted due to its independent release, it has received widespread critical acclaim. It has been called a "classic",[69] and praised as part "of the most vital rock-n-roll of the era".[70] Bikini Kill's second album Reject All American was released in 1996, and the band broke up the next year.[71]

Despite retrospective acclaim, at the time the band was criticized for excluding men, and even Rolling Stone described Bikini Kill's first album as "yowling and moronic nag-unto-vomit tantrums."[27][72] "My joke is always like, I didn't just hit the glass ceiling, I pressed my naked [breasts] up against it," Hanna said of that time.[27] Bikini Kill eventually called for a "media blackout" due to their perceived misrepresentation of the movement by the media.[73] Their pioneer reputation endures but, as Hanna recalls:

[Bikini Kill was] very vilified during the '90s by so many people, and hated by so many people, and I think that that's been kind of written out of the history. People were throwing chains at our heads – people hated us – and it was really, really hard to be in that band.[74]

Bratmobile

[edit]

Hailing from Eugene, Oregon, Bratmobile was a first-generation riot grrrl band that became the second-most prominent founding voice of the riot grrrl movement. In 1990, University of Oregon students Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman collaborated on feminist zine Girl Germs with Washington, D.C.'s Jen Smith, touching on sexism in their local music scenes.[61]

We were very encouraged by people like Tobi and Kathleen in Olympia, and we were like, "Oh let's do a band, let's do radio—we wanna [sic] have an all-girl radio show!"[11]

During spring 1991, Erin Smith, Christina Billotte (of Autoclave), and Jen Smith (no relation to Erin) joined Wolfe and Neuman in Bratmobile when the latter two temporarily relocated to Washington, D.C. Neuman and Erin Smith were previously introduced at a Nation of Ulysses show in Washington, D.C., in December 1990 by mutual friend Calvin Johnson.[50] Jen Smith had written in a letter to Wolfe, "We need to start a girl RIOT!"[61][75] Jen Smith proposed they collaborate with members of Bikini Kill on a zine called Girl Riot. When Neuman began the zine, she changed its title to riot grrrl, providing a networking forum for young women in the wider music scene and giving the movement its name.[61]

Erin Smith, Jen Smith, Billotte, Wolfe, and Neuman released only one tape together, titled Bratmobile DC.[76][77] Thereafter, Bratmobile became a trio with Wolfe, Neuman, and Erin Smith. They played their first show together as Bratmobile in July 1991, with Neuman on drums, Erin Smith on guitar, and Wolfe on vocals.[50]

Between 1991 and 1994 Bratmobile released the album Pottymouth and EP The Real Janelle on Kill Rock Stars, as well as The Peel Session.[78] Bratmobile toured with Heavens to Betsy in 1992 and broke up in 1994.[78]

International Pop Underground Convention

[edit]From August 20 – 25, 1991, K Records held an indie music festival in Olympia called the International Pop Underground Convention (or IPU).[79][80][81][82][83] A promotional poster reads:

As the corporate ogre expands its creeping influence on the minds of industrialized youth, the time has come for the International Rockers of the World to convene in celebration of our grand independence. Hangman hipsters, new mod rockers, sidestreet walkers, scooter-mounted dream girls, punks, teds, the instigators of the Love Rock Explosion, the editors of every angry grrrl zine, the plotters of youth rebellion in every form, the midwestern librarians and Scottish ski instructors who live by night, all are setting aside August 20–25, 1991 as the time.[36]

A mostly all-female bill on the first night, called "Love Rock Revolution Girl Style Now!" and later simply "Girl Night", signaled a major step in the movement.[79][80][81][82][59] The night was organized by Lois Maffeo, KAOS DJ Michelle Noel (who later organized the first Yoyo A Go Go in 1994), and Margaret Doherty.[79] The lineup featured Maffeo, Tobi Vail solo, Christina Billotte solo, Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy, Nikki McClure, Jean Smith of Mecca Normal, 7 Year Bitch, Kicking Giant, Rose Melberg, Kreviss, I Scream Truck, the Spinanes, and two side projects of Kathleen Hanna: Suture, with Sharon Cheslow of Chalk Circle (DC's first all-women punk band) and Dug E. Bird of Beefeater, and the Wondertwins with Tim Green of Nation of Ulysses.[79][81][82] It was here that so many zinester people who'd only known each other from networking, mail, or talking on the phone, finally met and were brought together by an entire night of music dedicated to, for, and by women.[51]

An exceptionally large number of independent bands played and collaborated within the Olympia music scene. The convention also featured bands such as Bikini Kill, Nation of Ulysses, Unwound, L7, the Fastbacks, Shadowy Men on a Shadowy Planet, Girl Trouble, The Pastels, Seaweed, Scrawl, Jad Fair, Thee Headcoats, Steve Fisk, Tsunami, Fugazi, Sleepyhead, The Mummies, and spoken-word artist Juliana Luecking.[79][83] This convention demonstrated a new relationship between audience and performers, dismantling the power dynamic of the past, for instance voicing anger at people harassing the female performers.[84]

Spread across North America

[edit]Exposure to Bikini Kill and then Bratmobile inspired other riot grrrl factions to spring up around the United States and Canada. Women in other regional punk music scenes across North America were encouraged to form their own bands and start their own zines.[11] While Bikini Kill, amongst other bands, frequently avoided attention from mainstream media outlets due to the fear that riot grrrl would be co-opted by corporate enterprises, in the few interviews they did take, they often made the movement out to be bigger than it was, claiming the music scene existed in cities far beyond its actual scope. This encouraged feminists to seek out said scenes, and when they couldn't find them, they created them on their own, further broadening riot grrrl's scope.[59]

From July 31 to August 2, 1992, the first Riot Grrrl Convention brought people together in Washington, D.C. for a weekend of performances and workshops on topics such as rape, sexuality, racism, domestic violence, and self-defense.[35][37] A promotional flier reads:

Calling all grrrls and women! The riot grrrls in and around Washington DC are organizing a three-day riot grrrl convention this summer. We invite all grrrl and feminist bands and performers, grrrl fanzine writers, and energetic grrrls and boys from across the country to contribute their skills, energy, anger, creativity and curiosity. We will be having at least three shows, as well as workshops on everything from self-defense, to how to run a soundboard and how to lay out a zine. Plus, there will be a lot of time to talk with other women about how we fit (or don't fit!) in the punk community.[85]

By 1994, riot grrrl had been discovered by the mainstream, and Bikini Kill were increasingly referred to as pioneers of the movement.[37] These bands credited with establishing the subculture of riot grrrl resisted being co-opted as heads of the movement broadly.[86] Dedicated to a DIY ethos, bands and artists encouraged grrrls to challenge hierarchies and self-produce work relating to their own experiences and identities.[87]

England

[edit]As Bikini Kill's music and zines spread throughout England in 1991–92, bands formed and were quick to embrace riot grrrl.[3] England had previously spawned such influential all-female or female-fronted punk bands as X-Ray Spex, The Slits, and The Raincoats that provided inspiration.[3][13]

Huggy Bear formed in 1991, calling themselves "girl-boy revolutionaries" in reference to both their political philosophy and the gender makeup of their band, and were based in Brighton and London.[3][13][88][89][90] Their debut EP was released in 1992, and in the same year they began working closely with Bikini Kill as riot grrrl's popularity peaked on both sides of the Atlantic.[3] This culminated in a 1993 split album on Catcall Records (Huggy Bear) and Kill Rock Stars (Bikini Kill) called Our Troubled Youth/Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah, the names of the Huggy Bear and Bikini Kill sides respectively.[89][91] Huggy Bear received widespread national attention after performing their third single "Her Jazz", a split release between Catcall and Wiiija Records, on The Word in 1993.[3][90][91] Kill Rock Stars had been co-founded in Olympia by Slim Moon and Tinuviel Sampson, while Catcall was founded by former Manchester punk zine City Fun writer Liz Naylor.[92][93] Naylor had met Bikini Kill's Kathy Wilcox by chance while they were each traveling in Europe in 1991, and Wilcox sent Naylor music and the first issues of Riot Grrrl and Jigsaw zines during their subsequent correspondence.[93]

Skinned Teen formed in London in 1992, when they were around 14 years old. They were included in British filmmaker Lucy Thane's documentary of the 1993 Bikini Kill/Huggy Bear UK tour titled It Changed My Life: Bikini Kill In The U.K.; the film also included The Raincoats and queercore band Sister George.[3][91][92][93][94][95][96] Thane, from Sheffield, had previously met the Raincoats' Ana da Silva at a Hole show after Hole covered a Raincoats song.[93] Thane filmed Bikini Kill and Huggy Bear for the entirety of their 1993 tour using borrowed film and video equipment.[93] Naylor was tour manager.[93] It Changed My Life premiered in 1993 at The Kitchen in New York City, during a film program curated by filmmaker Jill Reiter.[93]

UK zines that wrote about riot grrrl at the time included Girlfrenzy and Ablaze!.[91]

Decline and later developments

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

By the mid-nineties, riot grrrl had severely splintered. Many within the movement felt that the mainstream media had completely misrepresented their message, and that the politically radical aspects of riot grrrl had been subverted by the likes of the Spice Girls and their "girl power" message, or co-opted by ostensibly women-centered bands (though sometimes with only one female performer per band) and festivals like Lilith Fair.[97]

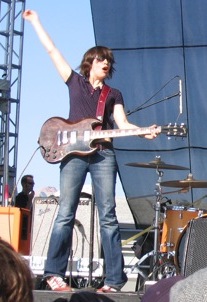

Of the original riot grrrl bands, Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy and Huggy Bear had split in 1994, Excuse 17 and most of the UK bands had split by 1995, and Bikini Kill and Emily's Sassy Lime (formed in Southern California in 1993) released their last records in 1996. However, Team Dresch were active as late as 1998, the Gossip were active from 1999, and Bratmobile reformed in 2000. Perhaps most prolific of all, Sleater-Kinney were active from 1994 to 2006, releasing seven albums.[98][99] Corin Tucker (Heavens to Betsy) and Carrie Brownstein (Excuse 17) had formed Sleater-Kinney in Olympia.[100]

Many of the women involved in riot grrrl are still active in creating politically charged music. Kathleen Hanna went on to found the electro-feminist post-punk "protest pop" group Le Tigre and later the Julie Ruin, Kathi Wilcox joined the Casual Dots with Christina Billotte of Slant 6, and Tobi Vail formed Spider and the Webs. Sleater-Kinney reformed the band in 2014 after an 8-year hiatus and have released four albums since, while Bratmobile reunited to release two albums, before Allison Wolfe began singing with other all-women bands, Cold Cold Hearts, and Partyline. Molly Neuman went on to play with New York punk band Love Or Perish and run her own indie label called Simple Social Graces Discos, as well as co-owning Lookout! Records and managing the Donnas, Ted Leo, Some Girls, and the Locust. Kaia Wilson of Team Dresch and multimedia artist Tammy Rae Carland went on to form the now-defunct Mr. Lady Records which released albums by the Butchies, Electrelane, Kaia Wilson, Le Tigre, Sarah Dougher, Sextional, Tami Hart, The Haggard, TJO TKO, The Movies, V for Vendetta, The Quails.[101][102] Bikini Kill played a string of shows in 2019[103] to present.[104]

Feminism and riot grrrl culture

[edit]Riot grrrl culture is often associated with third wave feminism, which also grew rapidly during the same early nineties timeframe. The movement of third-wave feminism focused less on laws and the political process and more on individual identity. The movement of third-wave feminism is said to have arisen out of the realization that women are of many colors, ethnicities, nationalities, religions and cultural backgrounds.[105] While multiracial feminist movements have existed prior to the third wave, the proliferation of technology during the early nineties allowed for easier networking amongst feminist groups. Riot grrrls used media spectacle to their advantage, crafting works from oppositional technologies such as zines, videography, and music.[106] The riot grrrl movement allowed women their own space to create music and make political statements about the issues they were facing in the punk rock community and in society. They used their music and publications to express their views on issues such as patriarchy, double standards against women, rape, domestic abuse, sexuality, and female empowerment.[107]

An undated, typewritten Bikini Kill tour flier answers the question "What is Riot grrrl?" with:

"[Riot Grrrl is ...] Because we girls want to create mediums that speak to US. We are tired of boy band after boy band, boy zine after boy zine, boy punk after boy punk after boy... Because we need to talk to each other. Communication and inclusion are key. We will never know if we don't break the code of silence... Because in every form of media we see ourselves slapped, decapitated, laughed at, objectified, raped, trivialized, pushed, ignored, stereotyped, kicked, scorned, molested, silenced, invalidated, knifed, shot, choked and killed. Because a safe space needs to be created for girls where we can open our eyes and reach out to each other without being threatened by this sexist society and our day to day bullshit."[108]

The riot grrrl movement encouraged women to develop their own place in a male-dominated punk scene. Punk shows had come to be understood as places where "women could make their way to the front of the crowd into the mosh pit, but had to 'fight ten times harder' because they were female, and sexually charged violence such as groping and rape had been reported."[109]

In contrast, riot grrrl bands would often actively invite members of the audience to talk about their personal experiences with sensitive issues such as sexual abuse, pass out lyric sheets to everyone in the audience, and often demand that the mosh boys move to the back or side to allow space in front for the girls in the audience.[64] The bands weren't always enthusiastically received at shows by male audience members. Punk Planet editor Daniel Sinker wrote in We Owe You Nothing:

The vehemence fanzines large and small reserved for riot grrrl – and Bikini Kill in particular – was shocking. The punk zine editors' use of 'bitches', 'cunts', 'man-haters', and 'dykes' was proof-positive that sexism was still strong in the punk scene.[110]

Kathi Wilcox said in a fanzine interview:

I've been in a state of surprise for several years about this very thing. I don't know why so-called punk rockers are so threatened by a little shake-up of the truly boring dynamic of the standard show atmosphere. How fresh is the idea of fifty sweaty hardcore boys slamming into each other or jumping on each others' heads? Granted, it's kind of cool to be on stage and have action in the front, much more inspiring than to look out at a crowd of zombies, but so often the survival-of-the-fittest principle is in operation in the pit, and what girl wants to go up against a pack of Rollins boys who usually only want to be extra mean to her anyway just to make her "prove" her place in the pit. This was the case when I was first going to shows, and it's sad that things haven't changed at all since. ... But it would have been so cool if at one of these shows someone onstage would have said, hey let's have more girls up in the front, just so I could have had more company and girls over to side could have seen better/been in the action. So yeah, we do encourage girls to the front, and sometimes when shows have gotten really violent (like when we were in England) we had to ask the boys to move to the side or the back because it was just too fucking scary for us, after several attacks and threats, to face another sea of hostile boy-faces right in the front.[111]

Kathleen Hanna later wrote: "It was also super schizo to play shows where guys threw stuff at us, called us cunts and yelled "take it off" during our set, and then the next night perform for throngs of amazing girls singing along to every lyric and cheering after every song."[60]

Many men were supporters of riot grrrl culture and acts. Calvin Johnson and Slim Moon have been instrumental in publishing riot grrrl bands on the labels they founded, K Records and Kill Rock Stars respectively. Alec Empire of Atari Teenage Riot said, "I was totally into the riot grrrl music, I see it as a very important form of expression. I learned a lot from that, way more maybe than from 'male' punk rock."[112] Dave Grohl and Kurt Cobain dated Kathleen Hanna and Tobi Vail (also respectively), and often played with Bikini Kill even after splitting with them; Kurt was a big fan of the Slits and even convinced the Raincoats to reform. He once said, "The future of rock belongs to women."[113] Many riot grrrl bands included male band members, such as Billy Karren of Bikini Kill or Jon Slade and Chris Rawley of Huggy Bear.

The New-York Historical Society's documentation on "Women & the American Story" said that "the riot grrrl movement struggled to recognize intersectionality" and therefore many women of color left when they felt their voices weren't being heard.[114] In 1997, punk musician Tamar-kali Brown created Sista Grrrl by and for Black women and girls, in response to the marginalization of women of color in riot grrrl.[115] Sista Grrrls was the name for Tamar-kali's New York punk group with three other Black women: Simi Stone, Honeychild Coleman, and Maya Sokora.[114] These four organized a series of punk shows, known as Sista Grrrl Riots, with Black women and girls who were in bands or performed solo.[116] The Slits' Ari Up opened one of the riots as a Sista Grrrl ally,[116] and Honeychild Coleman later toured as guitarist with the reformed Slits in 2010.[117]

Scholars have argued that riot grrrl remains relevant on a global scale because it engages with "everyday politics" or the ways that people in their day-to-day activities participate in or experience power dynamics.[118] It allows grrrls to connect their interests and contemporary lives to urgent political issues in personal and subversive ways.[119] One way riot grrrl achieved this was through language that centered young women and girls as political subjects with agency and power, in a way that broke away from historical models of feminism and radical speech.[120] This "history-in-the-making" approach aligned well with riot grrrl's devotion to DIY.[120]

Zines and publications

[edit]Even as the Seattle-area rock scene came to international mainstream media attention, riot grrrl remained a willfully underground phenomenon.[108] Most musicians shunned the major record labels, devotedly working instead with indie labels such as Kill Rock Stars, K Records, Slampt, Piao! Records, Simple Machines, Catcall, WIIIJA and Chainsaw Records.

Riot grrrl's momentum was also hugely supported by an explosion of creativity in homemade cut and paste, xeroxed, collage zines that covered a variety of feminist topics, frequently attempting to draw out the political implications of intensely personal experiences in a "privately public" space.[108] Zines often described experiences with sexism, mental illness, body image and eating disorders, sexual abuse, racism, rape, discrimination, stalking, domestic violence, incest, homophobia, and sometimes vegetarianism. Grrrl zine editors are collectively engaged in forms of writing and writing instruction that challenge both dominant notions of the author as an individualized, bodiless space and notions of feminism as primarily an adult political project.[121]

These zines were archived by zinewiki.com, and Riot Grrrl Press, started in Washington DC in 1992 by Erika Reinstein & May Summer.[122]

Bands often attempted to reappropriate derogatory phrases like "cunt", "bitch", "dyke", and "slut", writing them proudly on their skin with lipstick or fat markers. Kathleen Hanna was writing "slut" on her stomach at shows as early as 1992, intentionally fusing feminist art and activist practices.[20] Many of the women involved with queercore were also interested in riot grrrl, and zines such as Chainsaw by Donna Dresch, Sister Nobody, Jane Gets A Divorce and I (heart) Amy Carter by Tammy Rae Carland embody both movements. There were also national conventions like in Washington, D.C.,[35][37] or the Pussystock festival in New York City, as well as various subsequent indie-documentaries like Don't Need You: the Herstory of Riot Grrrl.

Other riot grrrl zines such as Ramdasha Bikceem's GUNK, started in 1990 when she was 15, focused on the intersections of punk, gender, and racism.[116] Bikceem, from New Jersey, had found out about riot grrrl zines after a friend became Tobi Vail's roommate in Olympia. Bikceem's band Gunk performed at the first Riot Grrrl Convention in D.C. in 1992.[123][124] In GUNK #4 Bikceem wrote about the politics of being a Black grrrl, "I'll go out somewhere with my friends who all look equally as weird as me, but say we get hassled by the cops for skating or something. That cop is going to remember my face a lot clearer than say one of my white girlfriends."[116] Mimi Thi Nguyen's Slant and Sabrina Margarita Alcantara-Tan's Bamboo Girl critiqued riot grrrl from the perspective of Asian American girls.[116][125][126] In 1997, Nguyen published the compilation zine Evolution of a Race Riot.[125]

In the mid-1990s, zines were also published on the Internet as e-zines.[127] Websites such as Gurl.com and ChickClick were created out of dissatisfaction of media available to women and parodied content found in mainstream teen and women's magazines.[128][129] Both Gurl.com and ChickClick had a message board and free web hosting services, where users could also create and contribute their own content, which in turn created a reciprocal relationship where women could also be seen as creators rather than consumers.[127][130]: 154

Starting during the fall of 2010, the "Riot Grrrl Collection" has been housed at New York University's Fales Library and Special Collections, as "The Fales Riot Grrrl Collection". The collection's primary mandate is "to collect unique materials that provide documentation of the creative process of individuals and the chronology of the [Riot Grrrl] movement overall".[131] Kathleen Hanna, Molly Neuman, Allison Wolfe, Ramdasha Bikceem, Johanna Fateman, Becca Albee (co-founder of Excuse 17), Lucy Thane, Tammy Rae Carland, and Mimi Thi Nguyen have donated primary source material.[131] The collection is the brainchild of Lisa Darms, Senior Archivist at the Fales Library. According to Jenna Freedman, a librarian who maintains a zine collection at Barnard College, "It's just essential to preserve the activist voices in their own unmediated work, especially because of the media blackout that they called for". Kathleen Hanna, while understanding no collection can replicate the concert experience, feels the collection is a safe place that will be "free from feminist erasure".[131][132]

Media misconceptions

[edit]At first most Riot Grrrls were open to using the media as a way to spread the word to other girls. Shortly thereafter, however, feeling that they had been misrepresented, trivialized, commercialized, and made into a new fad and trend, the Riot Grrrls changed their minds.[133]

As media attention increasingly focused on the emerging grunge and alternative rock scene in the mid-nineties, the term "Riot Grrrl" was often used as a catchall for female-fronted bands and applied to less political alternative rock acts. While many female-centric or all-women rock bands, such as Frightwig, Hole, 7 Year Bitch, Babes in Toyland, the Breeders, the Gits, Lunachicks, Liz Phair, Veruca Salt, and L7, shared similar DIY tactics and feminist ideologies with the riot grrrl movement, not all of these acts self-identified with the riot grrrl label.[3][13] "It used to frustrate me when posters would say 'all-girl band' or 'riot grrrl'," recalled L7's Donita Sparks. "We cheered loudly when we went to Italy: it said, 'Rock from the USA.'"[134] Courtney Love, in particular, felt the need to disassociate with Riot Grrrl as a whole:

As supportive as I am of them, there's a faction that says, "We don't know how to play, but we're not going to follow your male-measured idea of what good is." Look, good is Led Zeppelin II. That's fucking good. And I'm not going to sit here and say you're a good band when you suck. They're like, "But we're entitled to suck." Really? We work so hard to get good at what we do without covering up who we are as women.[40]

To their chagrin, in 1992 riot grrrls found themselves in the media spotlight of magazines from Seventeen to Newsweek.[135][136] Newsweek's headline was "Riot Girl is feminism with a loud happy face dotting the 'i'," and USA Today ran a headline saying "From hundreds of once pink, frilly bedrooms comes the young feminist revolution."[37] Fallout from the media coverage led to resignations from the movement, including Jessica Hopper, a teenage music critic who was at the center of the Newsweek article.[137] Hopper, later the author of The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic, said, "Some people were really upset because I talked to mainstream media about what I felt riot grrrl was...At the time there was much more of a chasm between the underground and the mainstream and people didn't want mainstream girls showing up to this, and I just thought, I didn't want to be part of something that wasn't for all women."[137] To ease tension, Kathleen Hanna called a "media blackout" for that year.

In an essay from January 1994 that had been included in the double compact disc release of Bikini Kill's first two albums, Tobi Vail responded to media misrepresentation of Bikini Kill and riot grrrl in general:

One huge misconception for instance that has been repeated over and over again in magazines we have never spoken to and also by those who believe these sources without checking things out themselves is that Bikini Kill is the definitive 'riot girl band' ... We are not in anyway 'leaders of' or authorities on the 'Riot Girl' movement. In fact, as individuals we have each had different experiences with, feelings on, opinions of and varying degrees of involvement with 'Riot Girl' and though we totally respect those who still feel that label is important and meaningful to them, we have never used that term to describe ourselves AS A BAND. As individuals we respect and utilize and subscribe to a variety of different aesthetics, strategies, and beliefs, both political and punk-wise, some of which are probably considered 'riot girl.'[138]

Sharon Cheslow stated in EMP's Riot Grrrl Retrospective documentary:

There were a lot of very important ideas that I think the mainstream media couldn't handle, so it was easier to focus on the fact that these were girls who were wearing barrettes in their hair or writing 'slut' on their stomach.

Corin Tucker stated:

I think it was deliberate that we were made to look like we were just ridiculous girls parading around in our underwear. They refused to do serious interviews with us, they misprinted what we had to say, they would take our articles, and our fanzines, and our essays and take them out of context. We wrote a lot about sexual abuse and sexual assault for teenagers and young women. I think those are really important concepts that the media never addressed.[139]

Other female-fronted punk bands, such as Spitboy, were less comfortable with the childhood-centered issues of much of the riot grrrl aesthetic, but nonetheless dealt explicitly with feminist and related issues as well.[140] Lesbian-centric Queercore[141] bands, such as Fifth Column, Tribe 8, Adickdid, the Third Sex, Excuse 17, and Team Dresch, wrote songs dealing with matters specific to women and their position in society, exploring issues such as both sexual[142] and gender identity.[143] A documentary film put together by a San Diego psychiatrist, Dr. Lisa Rose Apramian, Not Bad for a Girl, explored some of these issues in interviews with many of the musicians in the riot grrrl scene at the time.[144]

Criticism

[edit]The "Riot Grrrl" movement received criticism for not being inclusive enough. Emily White wrote for the Chicago Reader in 1992, "Riot Girls are often accused of being separatist: they want to form a life away from men and invent 'girl culture.'"[145] One major argument was that the movement focused on middle-class white women, alienating other kinds of women.[146][147][148] This criticism emerged early in the movement. In 1993, Ramdasha Bikceem wrote in her zine, Gunk,

Riot grrrl calls for change, but I question who it's including ... I see Riot Grrrl growing very closed to a very few i.e. white middle class punk girls.[108]

Riot grrrl, especially in the 1990s, focused heavily on the use of the body as "message boards" for public demonstration.[149] Riot grrrl faced similar issues as the original punk scene it was protesting against, in terms of its lack of intersectionality.[150] Black women, specifically, did not feel the counterculture was a safe-space to express their lived experiences, anger, and art.[150] Feeling excluded from the riot grrrl scene, Sista Grrrl Riots were created in the late 1990s by Tamar-kali Brown, Simi Stone, Honeychild Coleman, and Maya Sokora.[150] Sista Grrrls created a space by and for Black women to freely express themselves through punk. The Sista Grrrl movement was foundational to contemporary Afro-punk.[150] Tamar-kali later said, "I was a different type of girl. I was hearing what they were saying, but I was living in an environment where people were getting stabbed. Riot Grrrl felt like a bubblegum expression."[116]

Musician Courtney Love criticized the movement for being too doctrinaire and censorious:

Look, you've got these highly intelligent imperious girls, but who told them it was their undeniable American right not to be offended? Being offended is part of being in the real world. I'm offended every time I see George Bush on TV![151]

Some have suggested that, while riot grrrl bands worked to ensure their shows were safe spaces in which women could find solidarity and create their own subculture, some higher-profile riot grrrl bands participated in the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival, a trans-exclusionary event that had a "womyn-born womyn" policy. Former members of Le Tigre saw protests at their shows for having participated in the festival in 2001 and 2005.[152] However, Kathleen Hanna stated directly that she supported trans rights on her own Twitter account.[153] Additionally, JD Samson, another former member of Le Tigre, is genderfluid.[154]

Kathleen Hanna acknowledged some of these critiques in her zine April Fools' Day. When describing her traumas related to addiction, she said: "It seems to me that each addict functions within his/her one context in terms of race, gender, location, class, personality, access, etc. … so it would be ridiculous for me to try and write a 'manifesto' or a 'universal account' of how addiction works."[155] Hanna followed a legacy of privilege-checking in riot grrrl culture and the community commitment to differentiate between personal experiences and trauma from systemic oppression when necessary.[86] Riot grrrl activists have often tended to create themselves into marginalized subjects to strengthen their credibility within the subculture without recognizing their positionality.[86]

Legacy and resurgence

[edit]

In the foreword to the 2007 book, Riot Grrrl: Revolution Girl Style Now!, Beth Ditto writes of riot grrrl,

A movement formed by a handful of girls who felt empowered, who were angry, hilarious, and extreme through and for each other. Built on the floors of strangers' living rooms, tops of Xerox machines, snail mail, word of mouth and mixtapes, riot grrrl reinvented punk.[156]

Additionally, Ditto writes about riot grrrl's influence on her personally and on her music. She muses on the meaning of the movement for her generation,

Until I found riot grrrl, or riot grrrl found me I was just another Gloria Steinem NOW feminist trying to take a stand in shop class. Now I am a musician, a writer, a whole person.[156]

Many women write to Hanna in hopes of reviving the Riot Grrrl Movement. Hanna says, "Don't revive it, make something better".[157] In 2010 Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution became the first published history of the riot grrrl movement.[158][159] The author had also attended Riot Grrrl meetings herself.[160] As of 2019 there were approximately ten weekly riot grrrl meetings held nationwide and bands multiplying faster than can be counted.[4][18]

In 2013 Astria Suparak and Ceci Moss curated Alien She, an exhibition examining the impact of Riot Grrrl on artists and cultural producers. Alien She focuses on seven people whose visual art practices were informed by their contact with Riot Grrrl. Many of them work in multiple disciplines, such as sculpture, installation, video, documentary film, photography, drawing, printmaking, new media, social practice, curation, music, writing and performance—a reflection of the movement's artistic diversity and mutability.[162][163][164] It opened September 2013 at the Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, and ran through February the following year. It visited four subsequent art spaces (Vox Populi in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March – April 2014; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, October 2014 – January 2015; Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, California, February – May 2015; and Pacific Northwest College of Art: 511 Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary Craft in Portland, Oregon, September 3, 2015 – January 9, 2016[165]).

The term "grrrl" (or "grrl") itself has since been co-opted or used by agencies as diverse as advocacy on behalf of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (GRRL POWER 1.0 5-PACK / Memetics for the Ladies)[166] and a roller derby league in Singapore.[167]

The resurgence of riot grrrl is clearly visible in fourth-wave feminists worldwide who cite the original movement as an interest or influence on their lives and/or their work.[168][169] Some of them are self-proclaimed riot grrrls while others consider themselves simply admirers or fans. In an age where Internet is the most accessible platform for individuals to express themselves, the fourth-wave riot grrrl community has risen in popularity in recent years. Not only do these online platforms capture discussion regarding larger topics of intersectional oppression, but they also provide space for budding feminists to express smaller issues, such as the successes and challenges of their everyday lives. Young feminists have harnessed the internet as a forum for self-determinism and genuine, open expression: a core part of the riot grrrl message that allows young adults room to decide for themselves who they are.[23]

In January 2019, Bikini Kill announced their reunion tour for the first time since their last show in Tokyo 22 years ago. The Guardian stated in an article about reunion that the once-underground riot grrrl movement has gone mainstream due to word of mouth from celebrities and the increased attention to other modern feminist developments such as the Me Too movement. In the same article, drummer Tobi Vail stated her frustration with lack of social progress related to feminism.[103]

These same issues still exist, being a woman in public is very intense, whether it's in the public eye or just walking down the street at night by yourself.[103]

Vail also explained the aims of their reunion, that women discover the band and understand their history, especially those who did not have the opportunity to hear them during the original riot grrrl movement.

We're doing it because we want to be a part of this conversation about what feminism is in this moment.[103]

Global proliferation

[edit]

Since its beginnings, the riot grrrl movement was attractive to many women in varied cultures. Its spread across the world established bands in Brazil, Paraguay, Israel, Australia, Malaysia, and Europe,[170] and its globalization was also aided by the distribution of zines across Asia, Europe, and South America.[171] The discovery of riot grrrl provided women across the globe with access to an outlet that challenged the dominant culture's attitudes toward the female body through a form of self-expression[170] that previously was often inaccessible to women in non-western nations.[171] In addition to becoming a vehicle of expression for equality, bands in the genre affected the status quo of the music industry by challenging the gender norms that favoured male musicians.[172]

One of the most well-known bands to come out of the globalization of the riot grrrl movement is Pussy Riot, a Russian group formed in 2011 who self-identify as twenty-first century Russian riot grrrls.[171][173] Pussy Riot first came to popular media attention in 2012 when they staged a protest performance of "Punk Prayer" at the altar of Moscow's largest cathedral. The song includes an appeal to the Virgin Mary to banish Putin.[173][174][175] All three members of Pussy Riot were convicted of hooliganism and sentenced two years' imprisonment for desecration of the church.[176][177] Pussy Riot performs music with themes of feminism, LGBT rights, and opposition to the policies of Russian president Vladimir Putin, whom the group considers to be a dictator.[171][173][178]

See also

[edit]- All-female band

- Bikini Kill

- But I'm a Cheerleader

- C86

- Foxcore

- Girl Germs

- Guerrilla Girls

- Girl power

- It Changed My Life: Bikini Kill In The UK

- Kinderwhore

- Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains

- List of all-women bands

- List of riot grrrl bands

- The Punk Singer

- Punk ideology

- Queercore

- Radical Act

- Rock Against Sexism

- Tank Girl

- Women in music

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Feliciano, Steve. "the Riot Grrrl Movement". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ "It's Riot Grrrl Day in Boston: 13 Songs to rock out to at work". Sheknows.com. April 9, 2015. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McDonnell, Evelyn; Vincentelli, Elisabeth (May 6, 2019). "Riot Grrrl United Feminism and Punk. Here's an Essential Listening Guide". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Riot Grrrl Map". Google My Maps. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Garrison, Ednie-Kach (2000). "U.S. Feminism-Grrrl Style! Youth (Sub)Cultures and the Technologics of the Third Wave". Feminist Studies. 26 (1): 142. doi:10.2307/3178596. hdl:2027/spo.0499697.0026.108. JSTOR 3178596.

- ^ "When punk went feminist: the history of riot grrl". Gen Rise Media. May 12, 2020. Archived from the original on December 24, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Marion Leonard. "Riot grrrl." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 20 Jul. 2014.

- ^ Hopper, Jessica (January 20, 2011). "Riot Girl: still relevant 20 years on". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Kathleen (March 1, 2002). "Results of a misspent youth: Joan Jett's performance of female masculinity". Women's History Review. 11 (1): 89–114. doi:10.1080/09612020200200312. ISSN 0961-2025.

- ^ a b Meltzer, Marisa (February 15, 2010). Girl Power: The Nineties Revolution in Music. Macmillan. p. 42. ISBN 9781429933285.

- ^ a b c d Raha, Maria (2004). Cinderella's Big Score: Women of the Punk and Indie Underground. Seal Press. ISBN 978-1580051163. OCLC 226984652.

- ^ Anderson, Sini (2013). The Punk Singer. IFC Films.

- ^ a b c d Sheffield, Rob (March 27, 2020). "Riot Grrrl Album Guide: Essential LPs from Nineties rock's feminist revolution". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ Leyser, Yony (2017). Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution. Torch Films. OCLC 1114281127.

- ^ Jackson, Buzzy (2005). A Bad Woman Feeling Good: Blues and the Women Who Sing Them. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05936-6.

- ^ Forman-Brunell, Miriam (2001). Girlhood in American: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 563. ISBN 9781576072066.

- ^ a b c Schilt, Kristen (2003). "'A Little Too Ironic': The Appropriation and Packaging of Riot Grrrl Politics by Mainstream Female Musicians" (PDF). Popular Music and Society. 26 (1): 5. doi:10.1080/0300776032000076351. S2CID 37919089. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ a b White, Emily (September 24, 1992). "Revolution Girl-Style Now! Notes From the Teenage Feminist Rock 'n' Roll Undergroun". Chicago Reader. Sun-Time Media. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Rowe-Finkbeiner, Kristin (2004). The F-Word: Feminism In Jeopardy—Women, Politics and the Future. Seal Press. ISBN 978-1-58005-114-9.

- ^ a b Marcus, Sara (2010). Girls to the Front. Harper. p. 146. ISBN 9780061806360.

- ^ a b c Sabin, R. Punk Rock: So What?: The Cultural Legacy of Punk, (Routledge, 1999), ISBN 0415170303

- ^ a b c Piepmeier, Alison (2009). Girl Zines: making media, doing feminism. New York, N.Y.: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814767528. OCLC 326484782.

- ^ a b Garofalo, Gitana (1998). "Riot Grrrl: Revolutions From Within". Signs. 23 (3): 809–841. doi:10.1086/495289. JSTOR 3175311. S2CID 144109102.

- ^ Garland, Emma (November 6, 2014). "How Does Riot Grrrl Inform Feminism and Punk in 2014?". Vice. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2011). Bad reputation : the unauthorized biography of Joan Jett. Backbeat. ISBN 978-1-61713-077-9. OCLC 987795305.

- ^ Burke, Kevin (July 20, 2019). "Inciting The Riot Grrrl - Five Women Who Inspired A Movement". The Big Takeover. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Ryzik, Melena (June 3, 2011). "A Feminist Riot That Still Inspires". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Cochrane, Lauren (December 4, 2010). "Poly Styrene, rock's original riot grrrl, plans to bondage up Christmas". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Goodman, Lizzy (April 22, 2013). "Kim Gordon Sounds Off". Elle. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ McCabe, Allyson. "The Story of The Fabulous Stains and Riot Grrrl". NPR. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Monem, Nadine, ed. (2007). Riot Grrrl: Revolution Girl Style Now!. Black Dog Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-1906155018.

- ^ Baumgarten, Mark (May 25, 2012). "Love Rock Revolution". CityArts. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ True, Everett (2009). Nirvana : the biography. New York, New York: Hachette Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-3390-3. OCLC 830122168.

- ^ a b c d Marcus, Sara (2010). Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. Harper. pp. 35–38. ISBN 9780061806360.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Klein, Melissa (1997). "Duality and Redefinition: Young Feminism and the Alternative Music Community". In Heywood, Leslie; Drake, Jennifer (eds.). Third Wave Agenda. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3005-9.

- ^ a b Baumgarten, Mark (2012). Love Rock Revolution : K Records and the rise of independent music. Seattle: Sasquatch Books. ISBN 978-1570618222.

- ^ a b c d e f Keene, Linda (March 21, 1993). "Feminist Fury -- 'Burn Down The Walls That Say You Can't'". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Puncture magazine". puncturemagazine.com. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "How can we strategize DIY undergrounds forever?". www.dostoyevskywannabe.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ a b McDonnell, Evelyn; Powers, Ann. Rock She Wrote (Cooper Square Press, 1999), ISBN 0815410182

- ^ Dolan, Jon (October 9, 2020). "RS Recommends: Nineties Indie Rock as it Happened in the Pages of 'Puncture'". Rolling Stone Magazine. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Monem, Nadine, ed. (2007). Riot Grrrl: Revolution Girl Style Now!. Black Dog Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 978-1906155018.

- ^ a b c d Monem, Nadine, ed. (2007). Riot Grrrl: Revolution Girl Style Now!. Black Dog Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1906155018.

- ^ "Sun Dog Propaganda SDP01b - Banned in DC". Dischord Records. 2020. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Schilt, Kristen (2004). "'Riot Grrrl Is...': The Contestation over Meaning in a Music Scene". In Andy Bennett; Richard A. Peterson (eds.). Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual. Cultural studies: Musicology. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8265-1451-6. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Jovanovic, Rozalia (November 8, 2010). "A Brief Visual History of Riot Grrrl Zines". Flavorwire. Flavorpill Productions. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Marcus, Sara (2010). Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. Harper. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9780061806360.

- ^ Hartnett, Kevin (September 16, 2013). "Braini/ac: Countercultural zines come to Harvard". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Bikini Kill Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Marcus, Sara (2010). Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. Harper. pp. 55–71. ISBN 9780061806360.

- ^ a b c "WATCH: Riot Grrrl Retrospectives - 'Girl Night' at the 1991 International Pop Underground Convention". Museum of Pop Culture. May 28, 2020. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Chick, Steve (2007). Psychic Confusion: The Sonic Youth Story. Omnibus Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-85712-054-0. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ "Riot Grrrl 2 – Subcultures and Sociology". Archived from the original on March 23, 2024. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Collins, Kathleen (April 27, 2017). "We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement. AndiZeisler. New York: Public Affairs, 2016. 304 pp. $26.99 cloth". The Journal of Popular Culture. 50 (2): 417–420. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12539. ISSN 0022-3840. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Richards, Chris (November 19, 2012). "Bikini Kill in D.C.: Memories from Kathleen Hanna, Kathi Wilcox, Ian MacKaye, Jenny Toomey and Ian Svenonius". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c Schweitzer, Ally (October 29, 2014). "Too Punk For TV: Positive Force Documentary To Premiere In D.C." WAMU. Archived from the original on September 22, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ "The Tool Cassette Series". Simple Machines. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ Leitko, Aaron (December 18, 2009). "The Orange Line Revolution: Before the McMansions and the Cheesecake Factory, Arlington was home to some of the region's most storied punk residences". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Koch, Kerri. Don't Need You: The Herstory of Riot Grrrl. Urban Cowgirl Productions, 2005.

- ^ a b Hanna, Kathleen. "My Herstory". Letigreworld.com. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Barton, Laura (March 4, 2009). "Grrrl Power". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ "Kathleen Hanna | Bikini Kill". www.kathleenhanna.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Brockes, Emma (May 9, 2014). "What happens when a riot grrrl grows up?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Ankeny, Jason. "Bikini Kill | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 23, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Daly, Steve (March 24, 1994). "Joan Jett Lives Up to Her Bad Reputation". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Hutchinson, Kate (January 25, 2015). "Riot Grrrl: 10 of the Best". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ^ Appell, Glenn; Hemphill, David (2006). American Popular Music: A Multicultural History. Stamford, CT: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 427. ISBN 9780155062290.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (2000). Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 27. ISBN 9780312245603.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2000). Alternative Rock. San Francisco, CA: Miller Freeman/Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 196. ISBN 9780879306076.

- ^ Richards, Chris (November 18, 2012). "Bikini Kill was a girl punk group ahead of its time". The Washington Post. Washington, DC. Archived from the original on August 14, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ^ Moore, Sam (January 5, 2019). "'This is not a test': Bikini Kill have just announced their reunion". NME. Washington, DC. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Eddy, Chuck (February 4, 1993). "Bikini Kill". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Brooks, Katherine (November 29, 2013). "Punk Icon Kathleen Hanna Brings Riot Grrl Back To The Spotlight". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 16, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ Burbank, Megan (April 22, 2015). "Rebel Girl, Redux". Portland Mercury. Portland, OR. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ Andersen, Mark (2003). Dance of days : two decades of punk in the nation's capital. Mark Jenkins. New York, NY: Akashic Books. ISBN 1-888451-44-0. OCLC 52817401.

- ^ Huff, Chris (July 10, 2018). "Riot Grrrl and the true spirit of rock n' roll". Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Gunnery, Mark (March 8, 2019). "Rebel Girls: D.C. Women In Punk". WAMU. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Kelly, Christina (December 6, 2018). "Before #metoo, there was Riot Grrrl and Bratmobile". Grok Nation. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Nelson, Chris (October 9, 2006). "The day the music didn't die". The Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Moore, Ryan (2009). Sells Like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Culture, and Social Crisis. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814796030.

- ^ a b c Hopper, Jessica (May 13, 2011). "Riot Grrrl get noticed". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c Marcus, Sara (2010). Girls to the Front. Harper. ISBN 9780061806360.

- ^ a b O'Hara, Gail (August 19, 2021). "IPUC at 30! The International Pop Underground Convention Remembered by Those Who Were There on its 30th Anniversary". Chickfactor. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Leonard, Marion (2007). Gender in the Music Industry: Rock, Discourse and Girl Power. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9780754638629. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "DC Punk Archive, Ryan Shepard Collection: Flier for a Riot Grrrl convention July 31 to August 2". Dig DC. DC Public Library. Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c Spiers, Emily (2015). "'Killing Ourselves Is Not Subversive': Riot Grrrl from Zine to Screen and the Commodification of Female Transgression". Women (Oxford, England). 26: 1–21.

- ^ Dunn, Kevin (2012). "'We ARE the Revolution': Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing". Women's Studies. 41 (2): 136–157. doi:10.1080/00497878.2012.636334. S2CID 144211678.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (October 14, 1993). "Pop and Jazz in Review: Huggy Bear". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Du Noyer, Paul (2003). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music (1st ed.). Fulham, London: Flame Tree Publishing. p. 113. ISBN 1-904041-96-5.

- ^ a b Moakes, Gordon (October 20, 2008). "Huggy Bear: a tribute". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Petra (January 28, 2013). "Riot Grrrl: A 20 Year Retrospective". The Quietus. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Steiner, Melissa Rakshana (May 1, 2014). "Reviews: Bikini Kill". The Quietus. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lukenbill, Mark (May 12, 2016). "Someone Said Rebel Boy: Lucy Thane & Bikini Kill in the UK". Impose. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Thane, Lucy (May 14, 2010). "Bikini Kill in the U.K. 1993". Vimeo.com. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ Berman, Judy (May 16, 2016). "Spectacle's 'Grrrl Germs' Film Series Captures the Agony, Ecstasy, and Diversity of Riot Grrrl". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Adding Context: The Lucy Thane Riot Grrrl Videos". New York University. February 18, 2016. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Jul 10, 1997: Lilith Fair at Blockbuster Pavilion Phoenix, Arizona, United States | Concert Archives". www.concertarchives.org. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ^ Rife, Katie (April 4, 2017). "Riot grrrl grew up on Sleater-Kinney's Dig Me Out". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Shepherd, Julianne Escobedo (August 28, 2006). "Get Up". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Brownstein, Carrie (October 25, 2016). Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl: A Memoir. Penguin. ISBN 9780399184765. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Mr. Lady Records and Video ::: Bands". Archived from the original on December 4, 2004. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Mr. Lady Records collection". oac.cdlib.org. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Ewens, Hannah (January 9, 2019). "Riot grrrl pioneers Bikini Kill: 'We're back. It's intense'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ "Bikini Kill". bikinikill.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Fisher, J.A. (May 16, 2013). "Today's Feminism: A Brief Look at Third-Wave Feminism." Being Feminist". Wordpress. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ No Permanent Waves : Recasting Histories of U.S. Feminism. Nancy A. Hewitt. New Brunswick, N.J. 2010. ISBN 978-0-8135-4917-0. OCLC 642204450.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Schilt, Kristen. "The History of Riot Grrls in Music". The Feminist eZine. Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Darms, Lisa (June 11, 2013). The Riot Grrrl Collection. Feminist Press (CUNY). p. 168. ISBN 978-1558618220.

- ^ Belzer, Hillary. "Words + Guitar: The Riot Grrrl Movement and Third-Wave Feminism" (PDF). Communication, Culture & Technology Program. Georgetown University. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ We owe you nothing : Punk Planet : the collected interviews. Daniel Sinker. Chicago: Punk Planet Books. 2008. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-933354-32-3. OCLC 213411142.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "zine scan". Flickr.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ The Punk Years – Typical Girls. YouTube. Archived September 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Raphael, Amy (1996). Grrrls: Viva Rock Divas. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-14109-7.

- ^ a b "Punk Feminists". New-York Historical Society Museum & Library. New-York Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 3, 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ Kim, Hannah Hope Tsai (March 30, 2021). "'Moxie' Review: White Feminism and How Not to Write a Movie". The Harvard Crimson. Harvard University. Archived from the original on May 3, 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Bess, Gabby (August 3, 2015). "Alternatives to Alternatives: the Black Grrrls Riot Ignored". Vice. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Levitt, Karen (December 24, 2020). "Nobody puts Honeychild in a corner". Submission Beauty. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved May 6, 2023.

- ^ Dunn, Kevin (2014). "Pussy Rioting: The Nine Lives of the Riot Grrrl Revolution". International Feminist Journal of Politics. 16: 317–334. doi:10.1080/14616742.2014.919103. S2CID 146989637.

- ^ Şahin, Reyhan (2016). "Riot Grrrls, Bitchsm, and Pussy Power: Interview with Reyhan Şahin/Lady Bitch Ray". Feminist Media Studies. 16: 117–127. doi:10.1080/14680777.2015.1093136. S2CID 146144086. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ a b Lusty, Natalya (2017). "Riot Grrrl Manifestos and Radical Vernacular Feminism". Australian Feminist Studies. 32 (93): 219–239. doi:10.1080/08164649.2017.1407638. S2CID 148696287.

- ^ Comstock, Michelle. Grrl Zine Networks: Re-Composing Spaces of Authority, Gender, and Culture. La Jolla: n.p., September 3, 2013. PDF.

- ^ "Riot Grrrl". ZineWiki. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "Guide to the Ramdasha Bikceem Riot Grrrl Collection". Fales Library & Special Collections. January 24, 2022. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ "Ramdasha Bikceem Gunk Riot Grrrl Conference 1992" (video). YouTube. April 2, 2023. Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Laing, Olivia (June 29, 2013). "The art and politics of riot grrrl - in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Eriksson, Emma (March 1, 2021). "RRRevolution! Girl Style! Now!". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Oren, Tasha; Press, Andrea (May 29, 2019). The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Feminism. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 9781138845114.

- ^ Copage, Eric V. (May 9, 1999). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: NEW YORK ON LINE; Girls Just Want To ..." The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Macantangay, Shar (April 18, 2000). "Chicks click their way through the Internet". Iowa State Daily. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Shade, Leslie Regan (July 19, 2004). "Gender and the Commodification of Community". Community in the Digital Age: Philosophy and Practice. By Feenberg, Andrew. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 151–160. ISBN 9780742529595.

- ^ a b c "The Riot Grrrl Collection". Fales Library & Special Collections. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Soloski, Alexis (April 6, 2010). "Revolution, Girl-Style—Shhh!". Village Voice. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

In one corner of the hushed reading room of the Fales Library & Special Collections, housed on the third floor of New York University's Bobst Library, squats a strange object. Amid the gray carpeting, carved busts, glass-encased cabinets, and dreadful oil paintings crouches a two-drawer file cabinet covered in stickers that read "Mr. Lady," "Slut," "Pansy Division," "Giuliani Is a Jerk," "Suck It Boy," and "Free Mumia."