Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

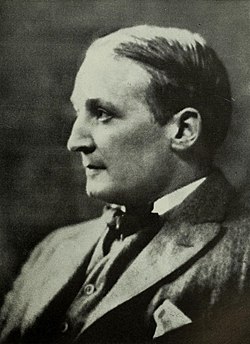

Robert J. Flaherty

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on the |

| Anthropology of art, media, music, dance and film |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Robert Joseph Flaherty, FRGS (/ˈflæ.ərti, ˈflɑː-/;[4] February 16, 1884 – July 23, 1951) was an American filmmaker who directed and produced the first commercially successful feature-length documentary film, Nanook of the North (1922). The film made his reputation and nothing in his later life fully equaled its success, although he continued the development of this new genre of narrative documentary with Moana (1926), set in the South Seas, and Man of Aran (1934), filmed in Ireland's Aran Islands. Flaherty is considered the father of both the documentary and the ethnographic film.

Flaherty was married to writer Frances H. Flaherty from 1914 until his death in 1951. Frances worked on several of her husband's films, and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Story for Louisiana Story (1948).

Early life

[edit]Flaherty was one of seven children born to prospector Robert Henry Flaherty (an Irish Protestant) and Susan Klockner (a German Catholic).

Due to exposure from his father's work as an iron ore explorer, he developed a natural curiosity for people of other cultures. Flaherty was an acclaimed still-photographer in Toronto. His portraits of American Indians and wild life during his travels are what led to the creation of his critically acclaimed Nanook of the North. It was his enthusiasm and interests in these people that sparked his need to create a new genre of film.[5]

In 1914, he married his fiancée Frances Hubbard. Hubbard came from a highly educated family, her father being a distinguished geologist. A graduate from Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, Hubbard studied music and poetry in Paris and was also secretary of the local Suffragette Society. Following their marriage, Frances Flaherty became a crucial part of Robert's success in film. Frances took on the role of director at times, and helped to edit and distribute her husband's films, even landing governmental film contracts for England.[6]

In 1909 he shared stories about information he was told by an Inuk man named George Weetaltuk, grandfather of Mini Aodla Freeman.[7] Flaherty said he met Weetaltuk while visiting the Hudson Bay in search of iron ore. In his Weetaltuk story, Flaherty published a detailed map of the Inuit region and shared information about the bay that Weetaltuk had told him. His writing about George Weetaltuk would go on to be published in his book, My Eskimo Friends: "Nanook of the North".[8]

Nanook of the North

[edit]In 1913, on Flaherty's expedition to prospect the Belcher Islands, his boss, Sir William Mackenzie, suggested that he take a motion picture camera along. He brought a Bell and Howell hand cranked motion picture camera. He was particularly intrigued by the life of the Inuit, and spent so much time filming them that he had begun to neglect his real work. When Flaherty returned to Toronto with 30,000 feet of film, the nitrate film stock was ignited in a fire started from his cigarette in his editing room. His film was destroyed and his hands were burned. Although his editing print was saved and shown several times, Flaherty was not satisfied with the results. "It was utterly inept, simply a scene of this or that, no relation, no thread of story or continuity whatever, and it must have bored the audience to distraction. Certainly it bored me."[9]

Flaherty was determined to make a new film, one following a life of a typical Inuk and his family. In 1920, he secured funds from Revillon Frères, a French fur trade company to shoot what was to become Nanook of the North.[10] On August 15, 1920, Flaherty arrived in Port Harrison, Quebec to shoot his film. He brought two Akeley motion-picture cameras which the Inuit referred to as "the aggie".[11] He also brought full developing, printing, and projection equipment to show the Inuit his film, while he was still in the process of filming. He lived in an attached cabin to the Revillon Frères trading post.

In making Nanook, Flaherty cast various locals in parts in the film, in the way that one would cast actors in a work of fiction. With the aim of showing traditional Inuit life, he also staged some scenes, including the ending, where Allakariallak (who acts the part of Nanook) and his screen family are supposedly at risk of dying if they could not find or build shelter quickly enough. The half-igloo had been built beforehand, with a side cut away for light so that Flaherty's camera could get a good shot. Flaherty insisted that the Inuit not use rifles to hunt[citation needed], though their use had by that time become common. He also pretended at one point that he could not hear the hunters' pleas for help, instead continuing to film their struggle and putting them in greater danger.[citation needed] [11]

Melanie McGrath writes that, while living in Northern Quebec for the year of filming Nanook, Flaherty had an affair with his lead actress, the young Inuk woman who played Nanook's wife. A few months after he left, she gave birth to his son, Josephie (December 25, 1921 – 1984), whom he never acknowledged. Josephie was one of the Inuit who were relocated in the 1950s to very difficult living conditions in Resolute and Grise Fiord, in the extreme north.[12] Corroboration of McGrath's account is not readily available and Flaherty never discussed the matter.

Nanook began a series of films that Flaherty made on the same theme of humanity against the elements. Others included Moana: A Romance of the Golden Age, set in Samoa, and Man of Aran, set in the Aran Islands of Ireland. All these films employ the same rhetorical devices: the dangers of nature and the struggle of the communities to eke out an existence.

Hollywood

[edit]Nanook of the North (1922) was a successful film, and Flaherty was in great demand afterwards. On a contract with Paramount to produce another film on the order of Nanook, he went to Samoa to film Moana (1926). He shot the film in Safune on the island of Savai'i where he lived with his wife and family for more than a year. The studio heads repeatedly asked for daily rushes but Flaherty had nothing to show because he had not filmed anything yet — his approach was to try to live with the community, becoming familiar with their way of life before writing a story about it to film. He was also concerned that there was no inherent conflict in the islanders' way of life, providing further incentive not to shoot anything. Eventually he decided to build the film around the ritual of a boy's entry to manhood. Flaherty was in Samoa from April 1923 until December 1924, with the film completed in December 1925 and released the following month. The film, on its release, was not as successful as Nanook of the North domestically, but it did very well in Europe, inspiring John Grierson to coin the word "documentary".

Before the release of Moana, Flaherty made two short films in New York City with private backing, The Pottery Maker (1925) and The Twenty-Four Dollar Island (1927). Irving Thalberg of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer invited Flaherty to film White Shadows in the South Seas (1928) in collaboration with W. S. Van Dyke, but their talents proved an uncomfortable fit, and Flaherty resigned from the production. Moving to Fox Film Corporation, Flaherty spent eight months working on the Native American documentary Acoma the Sky City (1929), but the production was shut down, and subsequently Flaherty's footage was lost in a studio vault fire. He then agreed to collaborate with F. W. Murnau on another South Seas picture, Tabu (1931). However, this combination proved even more volatile, and while Flaherty did contribute significantly to the story, the finished film, originally released by Paramount Pictures, is essentially Murnau's.

Britain

[edit]After Tabu, Flaherty was considered finished in Hollywood, and Frances Flaherty contacted John Grierson of the Empire Marketing Board Film Unit in London, who assigned Flaherty to the documentary Industrial Britain (1931). By comparison to Grierson and his unit, Flaherty's habitual working methods involved shooting relatively large amounts of film in relation to the planned length of the eventual finished movie, and the ensuing cost overruns obliged Grierson to take Flaherty off the project, which was edited by other hands into three shorter films.

Flaherty wrote a novel about the sea called The Captain's Chair which was published in 1938 by Scribner. This was presented on BBC Television in November that year, under the title The Last Voyage of Captain Grant, adapted and directed by Denis Johnston.[13][14]

Flaherty's career in Britain ended when producer Alexander Korda removed him from the production Elephant Boy (1937), re-editing it into a commercial entertainment picture.

Ireland

[edit]Producer Michael Balcon took Flaherty on to direct Man of Aran (1934), which portrayed the harsh traditional lifestyle of the occupants of the isolated Aran Islands off the west coast of Ireland. The film was a major critical success, and for decades was considered in some circles an even greater achievement than Nanook. As with Nanook, Man of Aran showed human beings' efforts to survive under extreme conditions: in this case, an island whose soils were so thin that the inhabitants carried seaweed up from the sea to construct fields for cultivation. Flaherty again cast locals in the various fictionalized roles, and made use of dramatic recreation of anachronistic behaviors: in this case, a sequence showing the hunting of sharks from small boats with harpoons, which the islanders had by then not practiced for several decades. He also staged the film's climactic sequence, in which three men in a small boat strive to row back to shore through perilously high, rock-infested seas.

Last years

[edit]Back in the United States, Pare Lorentz of the United States Film Service hired Flaherty to film a documentary about US agriculture, a project which became The Land. Flaherty and his wife covered some 100,000 miles, shooting 25,000 feet of film, and captured a series of striking images of rural America. Among the themes raised by Flaherty's footage were the challenge of the erosion of agricultural land and the Dust Bowl (as well as the beginning of effective responses via improved soil conservation practices), mechanization and rural unemployment, and large-scale migration from the Great Plains to California. In the latter context, Flaherty highlighted competition for agricultural jobs between native-born Americans and migrants from Mexico and the Philippines.

The film encountered a series of obstacles. After production had begun, Congress abolished the United States Film Service, and the project was shunted to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). With America's entry to World War II approaching, USDA officials (and the film's editor Helen van Dongen) attempted to reconcile Flaherty's footage with rapidly changing official messages (including a reversal of concern from pre-war rural unemployment to wartime labor shortages). Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, officials grew apprehensive that the film could project an unduly negative image of the US internationally, and although a prestige opening was held at the Museum of Modern Art in 1942, the film was never authorized for general release.[15]

Louisiana Story (1948) was a Flaherty documentary shot by himself and Richard Leacock, about the installation of an oil rig in a Louisiana swamp. The film stresses the rig's peaceful and unproblematic coexistence with the surrounding environment, and it was in fact funded by Standard Oil, a petroleum company. The main character of the film is a Cajun boy. The poetry of childhood and nature, some critics argue, is used to make exploration for oil look beautiful. Virgil Thomson composed the music for the film.

Flaherty was one of the makers of The Titan: Story of Michelangelo (1950), which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. The film was a re-edited version of the German/Swiss film originally titled Michelangelo: Life of a Titan (1938), directed by Curt Oertel. The re-edited version put a new English narration by Fredric March and musical score onto a shorter edit of the existing film. The new credits include Richard Lyford as director and Robert Snyder as producer. The film was edited by Richard Lyford.[16]

Also in the early 1950s, Lowell Thomas, an investor and the most prominent promotor of Cinerama, was eager to secure his "good friend" Flaherty's endorsement of this pioneer film technology. Reportedly, Flaherty was very excited about Cinerama's promise, and for about a month, he tested the camera invented by Fred Waller. But "just as he was to set forth round the world" to shoot Cinerama footage with Waller's camera, he died, which prompted Thomas to find and hire a new film crew and also join forces with Mike Todd.[17]

Legacy

[edit]Flaherty is considered a pioneer of documentary film. He was one of the first to combine documentary subjects with a fiction-film-like narrative and poetic treatment.

A self-proclaimed explorer, Flaherty was inducted into the Royal Geographic Society of England for his (re)discovery of the main island of the Belcher group in Hudson Bay in 1914.[18]

Flaherty Island, one of the Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay, is named in his honor.[18]

The Flaherty Seminar is an annual international forum for independent filmmakers and film-lovers, held in rural upstate New York at Colgate University in mid June. The festival was founded in Flaherty's honor by his widow in 1955.[19]

Flaherty's contribution to the advent of the documentary is scrutinized in the 2010 British Universities Film & Video Council award-winning and FOCAL International award-nominated documentary A Boatload of Wild Irishmen,[20] written by Professor Brian Winston of University of Lincoln, UK, and directed by Mac Dara Ó Curraidhín. The film explores the nature of "controlled actuality" and sheds new light on thinking about Flaherty. The argument is made that the impact of Flaherty's films on the indigenous peoples portrayed changes over time, as the films become valuable records for subsequent generations of now-lost ways of life.[21] The film's title derives from Flaherty's statement that he had been accused, in the staged climactic sequence of Man of Aran, of "trying to drown a boatload of wild Irishmen".

In 1994, Flaherty was portrayed by Charles Dance in the Canadian drama film Kabloonak, a dramatization of the making of Nanook of the North from an Inuit perspective.[22]

The wife of Robert Joseph Flaherty's grandson, Louise Flaherty,[23] is the co-founder of Canada's first independent Inuk publishing house, Inhabit Media. She is also an author, educator and politician.

Awards

[edit]- BAFTA presents the Robert J. Flaherty Award for best one-off documentary.[24]

- Academy Award Oscar - Best Documentary Feature 1950 - The Titan: Story of Michelangelo

- 1913, Fellow, Royal Geographical Society[25]

Filmography

[edit]

Films

[edit]- Nanook of the North (1922)

- "The Pottery Maker" (1925)

- Moana (1926)

- "Twenty-Four-Dollar Island" (1927)

- Man of Aran (1934)

- "Oidhche Sheanchais (A Night of Storytelling)" (1935)

- Elephant Boy (1937; with Zoltan Korda)

- The Land (1942; made for the U.S. Department of Agriculture)[26]

- Louisiana Story (1948)

Other work

[edit]- White Shadows in the South Seas (1928; uncredited footage)

- Acoma the Sky City (1929; unfinished film)

- Tabu (1931; screenplay with F. W. Murnau)

- "Industrial Britain" (1933; co-producer with John Grierson)[27]

- "The Glassmakers of England" (1935; co-producer with John Grierson)[28]

- "The English Potter" (1935; co-producer with John Grierson)

- The Titan: Story of Michelangelo (1950; co-producer with Ralph Alswang and Robert Snyder)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Mrs. Robert Flaherty, Widow Of Documentary Filmmaker". The New York Times. June 24, 1972.

- ^ Royte, Elizabeth (April 8, 2007). "The Long Exile - Melanie McGrath - Books - Review". The New York Times.

- ^ "Martha of the North". National Canadian Film Day.

- ^ "Flaherty". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ McLane, Betsy A. (2012). A new history of documentary film (2nd ed.). New York: Continuum. ISBN 9781441124579. OCLC 758646930.

- ^ Christopher, Robert J. (2005). Robert and Frances Flaherty: a documentary life, 1883-1922. Flaherty, Frances Hubbard; Flaherty, Robert Joseph. Montreal [Que.]: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0773528768. OCLC 191819179.

- ^ "Arctic Profiles - George Weetaltuk (ca. 1862-1956)" (PDF). Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ "Map of Belcher Islands". World Digital Library. 1909. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ The World of Robert Flaherty, Richard Griffith

- ^ The Innocent Eye, Arthur Calder-Marshall

- ^ a b Year of the Hunter CBC documentary

- ^ Throughout Melanie McGrath's The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic. ISBN 0-00-715796-7 (London: Fourth Estate, 2006). ISBN 1-4000-4047-7 (New York: Random House, 2007).

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk. November 9, 1938. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014.

- ^ "The Last Voyage of Captain Grant". November 1, 1938 – via IMDb.

- ^ Starr, Cecile (2000). "The Land". In Pendergast, Tom; Pendergast, Sara (eds.). International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers. Vol. 1 — Films (4 ed.). St. James Press. pp. 667–669. ISBN 1-55862-450-3. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (January 23, 1950). "THE SCREEN IN REVIEW; 'The Titan--Story of Michelangelo,' an Imaginative Cinema Presentation, Opens at Little Carnegie". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ Hirsch, Foster (2023). Hollywood and the Movies of the Fifties (First ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 145–146. ISBN 9780307958921.

- ^ a b McLane, Betsy A. (2012). A New History of Documentary Film (2nd ed.). New York: Continuum. p. 21. ISBN 9781441124579. OCLC 758646930.

Flaherty (re)discovered the main island of the Belcher group in Hudson Bay in 1914, and it was subsequently named for him. Flaherty often defined himself an explorer, and was proud of his induction into the Royal Geographic Society of England for this discovery.

- ^ "The Flaherty". The Flaherty. August 3, 2022.

- ^ 'A Boatload of Wild Irishmen

- ^ A preview/trailer for A Boatload of Wild Irishmen can be viewed online. Accessed on 4/23/11 at: http://www.blip.tv/file/4246118

- ^ "Kabloonak captures the North". Montreal Gazette, September 16, 1994.

- ^ "Flaherty, Louise | Inuit Literatures ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᓪᓚᒍᓯᖏᑦ Littératures inuites". inuit.uqam.ca. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ "BAFTA's Robert J. Flaherty Award". Archived from the original on March 25, 2010.

- ^ Christopher, Robert J.; Frances Hubbard Flaherty; Robert Joseph Flaherty (2005). Robert and Frances Flaherty: a documentary life, 1883-1922. McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 128. ISBN 0-7735-2876-8.

Royal.

- ^ Released as a VHS videotape; see The Land (VHS). Film Preservation Associates. OCLC 10227840.

- ^ Barsam, Richard Meran (1992). Nonfiction Film: A Critical History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20706-7.

- ^ Low, Rachael (March 27, 2020). The History of British Film (Volume 5): The History of the British Film 1929 - 1939: Documentary and Educational Films of the 1930's. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-20661-0.

Further reading

[edit]- — (August 1922). "How I Filmed "Nanook Of The North": Adventures With The Eskimos To Get Pictures Of Their Home Life And Their Battles With Nature To Get Food". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XLIV: 553–560. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- — (September 1922). "Life Among The Eskimos: The Difficulties And Hardships Of The Arctic. how Motion Pictures Were Secured of Nanook Of The North And His Hardy And Generous People". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XLIV: 632–640. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- Frances H. Flaherty, The Odyssey of a Filmmaker: Robert Flaherty's Story (Urbana, IL: Beta Phi Mu, 1960). Beta Phi Mu chapbook no. 4

- Calder-Marshall, Arthur, The Innocent Eye; The Life of Robert J. Flaherty. Based on research material by Paul Rotha and Basil Wright (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1966)

- Karzan Kardozi. 100 Years of Cinema, 100 Directors, Vol 3: Robert Flaherty. (Sulaymaniyah: Xazalnus Publication, 2020)

- Kodó, Krisztina (April 17, 2023). "Local and Universal: The Canadian Inuit and the Irish Aran Islanders in the Films of Robert J. Flaherty". Open Library of Humanities. 36 (1). doi:10.16995/olh.8866. ISSN 2056-6700.

- Murphy, William Thomas, Robert Flaherty: A Guide to References and Resources (Boston: G. K. Hall and Company, 1978)

- Paul Rotha, Flaherty: A Biography Edited b y Jay Ruby.(University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984)

- Barsam, Richard, The Vision of Robert Flaherty: The Artist As Myth and Filmmaker (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1988)

- Christopher, Robert J., Robert & Frances Flaherty: A Documentary Life 1883-1922 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005)

- McGrath, Melanie, The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic. ISBN 0-00-715796-7 (London: Fourth Estate, 2006). ISBN 1-4000-4047-7 (New York: Random House, 2007). The story of forced removal of Inuit in Canada in 1953, including Flaherty's illegitimate Inuit son Josephie.

- Ramsaye, Terry, "Flaherty, Great Adventurer," Photoplay, May 1928, p. 58.

External links

[edit]- Robert J. Flaherty at IMDb

- Robert Flaherty biography and credits at the BFI's Screenonline

- Senses of Cinema: Great Directors Critical Database

- Robert Flaherty Film Seminar

- Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story

- Hand drawn map by an Inuk man named Wetalltok given to Flaherty in 1919

- Literature on Robert J. Flaherty

- Robert Flaherty by Amos Vogel

- Robert J. Flaherty Photogravure Prints at Dartmouth College Library

- Finding aid to Robert J. Flaherty papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.