Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

STS-115

View on Wikipedia

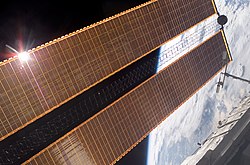

The ISS above Earth, following the installation of a new truss segment and solar arrays during STS-115 | |

| Names | Space Transportation System-115 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | ISS assembly |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2006-036A |

| SATCAT no. | 29391 |

| Mission duration | 11 days, 19 hours, 6 minutes, 35 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 7,840,000 kilometres (4,870,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 188 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Atlantis |

| Launch mass | 122,397 kg (orbiter)[1] |

| Landing mass | 90,573 kilograms (199,679 lb)[2] |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 6 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | September 9, 2006, 15:14:55 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy, LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | September 21, 2006, 10:21:30 UTC |

| Landing site | Kennedy, SLF Runway 33 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 157.4 kilometres (97.8 mi)[3] |

| Apogee altitude | 226.6 kilometres (140.8 mi) |

| Inclination | 51.6 degrees |

| Period | 91.6 minutes |

| Docking with ISS | |

| Docking port | PMA-2 (Destiny forward) |

| Docking date | September 11, 2006, 10:46 UTC |

| Undocking date | September 17, 2006, 12:50 UTC |

| Time docked | 6 days, 2 hours, 4 minutes |

(L-R) Heidemarie M. Stefanyshyn-Piper, Christopher J. Ferguson, Joseph R. Tanner, Daniel C. Burbank, Brent W. Jett Jr., Steven MacLean | |

STS-115 was a Space Shuttle mission to the International Space Station (ISS) flown by Space Shuttle Atlantis. It was the first assembly mission to the ISS after the Columbia disaster, following the two successful Return to Flight missions, STS-114 and STS-121. STS-115 launched from LC-39B at the Kennedy Space Center on September 9, 2006, at 11:14:55 EDT (15:14:55 UTC).

The mission is also referred to as ISS-12A by the ISS program. The mission delivered the second port-side truss segment (ITS P3/P4), a pair of solar arrays (2A and 4A), and batteries. A total of three spacewalks were performed, during which the crew connected the systems on the installed trusses, prepared them for deployment, and did other maintenance work on the station.

STS-115 was originally scheduled to launch in April 2003. The Columbia accident in February 2003 pushed the date back to August 27, 2006, which was again moved back for various reasons, including a threat from Tropical Storm Ernesto and the strongest lightning strike to ever hit an occupied shuttle launchpad.

Crew

[edit]| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Fourth and last spaceflight | |

| Pilot | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Second and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 Flight Engineer |

Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Fourth and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 4 | First spaceflight | |

| Note: The P3/P4 Truss segment and batteries were so heavy (more than 17.5 short tons, or roughly 16 metric tons) that the crew count was reduced from seven to six.[4] | ||

Crew notes

[edit]Canadian Space Agency astronaut MacLean became the first Canadian to operate Canadarm2 and its Mobile Base in space as he was handed a new set of solar arrays from Ferguson and Burbank controlling the original Canadian robotic arm, the Canadarm. MacLean performed a spacewalk, becoming only the second Canadian, after Chris Hadfield to do so.

The mission patch worn on the clothing used by the astronauts of STS-115 was designed by Graham Huber, Peter Hui, and Gigi Lui, three students at York University in Toronto, Ontario, the same university that Steve MacLean attended. The students also designed Steve MacLean's personal patch for this mission.[5]

Mission payloads

[edit]The primary payload was the second left-side ITS P3/P4 Truss segment, a pair of solar arrays, and associated batteries.

Mission objectives

[edit]- Delivery and installation of two truss segments (P3 and P4)

- Delivery and deployment of two new solar arrays (4A and 2A)

- Perform three spacewalks to connect truss segments, remove restraints on solar arrays, and prepare the station for the next assembly mission by STS-116

Crew seat assignments

[edit]| Seat[6] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the flight deck. Seats 5–7 are on the mid-deck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jett | ||

| 2 | Ferguson | ||

| 3 | MacLean | Stefanyshyn-Piper | |

| 4 | Burbank | ||

| 5 | Tanner | ||

| 6 | Stefanyshyn-Piper | MacLean | |

| 7 | Unused | ||

Mission background

[edit]NASA managers decided to move the STS-115 launch date forward to August 27 to obtain better lighting conditions to photograph the external tank. This occurred before with STS-31 and STS-82.[7] The launch window was co-ordinated with the Soyuz TMA-9 launch in mid-September, which delivered a new ISS crew and fresh supplies to the station. The Soyuz spacecraft operationally did not dock to the station while the Space Shuttle was there.[8]

The mission marks:[3]

- 147th NASA crewed space flight.

- 116th space shuttle flight since STS-1.

- 27th flight of Atlantis.

- 91st post-Challenger mission.

- 3rd post-Columbia mission.

- 1st post-Columbia mission of Atlantis.

Mission timeline

[edit]Launch preparations

[edit]

Atlantis was rolled out from the Orbiter Processing Facility to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on July 24, 2006. It was lowered onto the mobile launcher platform on July 26 and rolled out to Pad 39B in the early morning hours of August 2. The rollout was scheduled for July 31, but a storm in the vicinity of the Kennedy Space Center resulted in a delay of two days from fears of the orbiter being hit by lightning, which could cause immeasurable damage.

On the weekend of August 5 to 6, 2006, engineers completed a "flight readiness" check of the shuttle's main engines, which were deemed ready for launch. The crew arrived at the Kennedy Space Center August 7, 2006, for four days of launch rehearsals, including a practice countdown August 10.[9]

Top NASA managers held a Flight Readiness Review (FRR) meeting August 15–16, 2006 to finalize the launch date.[10] Foam loss from the external tank was a key issue at this meeting because on August 13, 2006, NASA announced there was an average amount of loss from the external tank of STS-121, the previous mission.[11] Columbia's demise was due to a piece of foam, shed from its external tank, striking the shuttle's left wing during launch and causing a hole that was breached during re-entry.

The meeting also discussed problems with the bolts securing the shuttle's Ku-band antenna, which might not have been threaded correctly. The installation had been in place for several flights and hadn't experienced any problems.[12] At the end of the two-day meeting, NASA managers had decided to proceed with the launch on August 27, 2006. However, on August 18, 2006, NASA decided to replace the antenna bolts with Atlantis still on the launch pad. NASA had no procedure to replace these on the pad, but the work was nonetheless completed by August 20, without affecting the planned launch date.[13]

On August 25, 2006, a direct lightning strike, the most powerful recorded at Kennedy Space Center, hit the lightning rod atop the launch pad.[14] As a result, on August 26 the Mission Management Team ordered the mission postponed for at least 24 hours to assess damage.[15] On August 27, the decision was made to postpone the launch for another 24 hours, making the earliest possible launch date August 29, 2006, still unassured that there was no damage from the lightning strike and taking into account the possible threat from Hurricane Ernesto.

On August 28, 2006, it was decided to postpone the launch and rollback Atlantis to the VAB after updated forecasts projected Hurricane Ernesto would regain its strength and pass closer to Kennedy Space Center than previously anticipated.[16] NASA began rolling back the shuttle on August 29, 2006, in the late morning, but by early afternoon the decision was made to move Atlantis back to the launch pad (something that has never been done before) to weather out Tropical Storm Ernesto instead. The change came after weather forecasters determined that the storm wouldn't hit Kennedy Space Center as forcefully as they once thought. Its peak winds were expected to be less than 79 mph (126 kilometers per hour), NASA's limit for keeping the shuttle outdoors.[17][18][19]

By the early morning of August 31, 2006, the storm had passed and inspection teams began a survey for damage to the launch facilities. Only three problems were discovered, all of which were simple repairs. A target date for launch was set for September 6 with the option to launch for another two days after NASA and Russian space managers agreed to extend the launch window by one day.[20][21] On the morning of September 3, 2006, the official countdown began at the T minus 43-hour mark, with about 30 hours of scheduled holds. In the early morning of September 6, 2006, engineers observed an apparent internal short when one of the three electricity producing fuel cells was powered up. When engineers couldn't figure out the problem in time, the launch was scrubbed for the day to further analyze the fuel cell problem.[22] Late Wednesday evening NASA managers decided that they would not attempt a launch on Thursday, and scheduled the next launch attempt for September 8, 2006. Originally they had ruled out September 9 as a potential launch date due to a conflict with the planned Russian Soyuz mission Soyuz TMA-9, which was scheduled to, and did, launch on September 18, 2006. This caused some news agencies to report that Friday as the last chance for a launch until October.[23]

September 8 (Launch attempt 1)

[edit]On the morning of September 8, 2006, it was reported that one of the engine cut-off (ECO) sensors in the external tank had failed.[24] About half an hour before the scheduled launch time, NASA announced it had decided to delay the launch for another 24 hours while the fuel was drained out of the external tank and the problem assessed.[25] The sensor in question, ECO sensor No. 3, was proved to be faulty when it indicated that there was still liquid hydrogen in the external tank despite all of it being drained out. The other three ECO sensors correctly indicated a dry tank; and as long as they didn't start to malfunction, NASA could allow a launch with three out of the four ECO sensors operational.[26]

| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 Sep 2006, 11:40:37 am | Scrubbed | — | Technical | 8 Sep 2006, 10:52 am (T−9:00 hold) | 70 | Engine cut-off (ECO) sensor failure.[27] |

| 2 | 9 Sep 2006, 11:14:55 am | Success | 0 days 23 hours 34 minutes | 80 |

September 9 (Flight day 1, Launch)

[edit]

On September 9, 2006, all the engine cut-off sensors were working properly, and following a flawless countdown, at 15:15 UTC (11:15 EDT), Atlantis lifted off the launch pad to the International Space Station.[28][29] As Atlantis launched, the International Space Station was 350 kilometres (220 mi; 190 nmi) above the northern Atlantic Ocean, between Greenland and Iceland.[29]

During the climb to orbit, Mission Control asked the crew to reconfigure a cooling system that apparently had ice build up. The reconfiguration cleared the system, called the Flash Evaporator System, and it operated normally. Temporary ice in that cooling unit is not uncommon and has occurred on previous missions.[29]

Moments after main engine cutoff, 8.5 minutes after liftoff, Tanner and MacLean used hand-held video and digital still cameras to document the external tank after it separated from the shuttle. That imagery, as well as imagery gathered by cameras in the shuttle's umbilical well where the tank was connected, was transmitted to the ground for review.[29]

September 10 (Flight day 2)

[edit]

During their first full day in space, the crew thoroughly examined Atlantis with the Orbiter Boom Sensor System, the 15 meter (50-foot) long extension for the shuttle's robotic arm. Pilot Chris Ferguson and mission specialists Dan Burbank and Steve MacLean performed a slow, steady inspection of the reinforced carbon-carbon panels along the leading edge of Atlantis' starboard and port wings and the nose cap.[30]

The crew worked ahead of schedule for most of the day readying the ship for docking and preparing for the mission's three planned extra-vehicular activities (EVA). Mission specialists Joe Tanner and Heide Stefanyshyn-Piper checked out the spacesuits and tools that they, Burbank and MacLean used during spacewalks set for Days 4, 5, and 7. The spacewalks installed the girder-like P3/P4 truss, deploy new solar arrays, and prepare them for operation.[30]

On the space station, Expedition 13 Flight Engineer Jeffrey Williams prepared the orbiting laboratory for Atlantis' arrival on Day 3. He readied the digital cameras that was used to take high-resolution photos of the shuttle's heat shield. With help from Commander Pavel Vinogradov, Williams pressurized the Pressurized Mating Adapter 2 at the end of the Destiny Laboratory Module, where Atlantis later docked. Vinogradov also prepacked equipment to be returned.[30]

September 11 (Flight day 3)

[edit]

Prior to docking, Jett flew Atlantis through an orbital back flip while stationed about 180 meters (600 feet) below the space station. The maneuver allowed the Expedition 13 crew to take a series of high-resolution photographs of the orbiter's heat shield.[31]

At about 10:46 UTC Atlantis docked with the International Space Station, and almost two hours later the hatch between them was opened, and the crew was welcomed aboard the station at 12:35 UTC.[31]

Following docking, Ferguson and Burbank attached the shuttle's robotic Canadarm to the 17.5-ton P3/P4 truss, lifted it from its berth in the payload bay, and maneuvered it for handover to the station's Canadarm2.[31]

After hatch opening, MacLean and Expedition 13 Flight Engineer Jeff Williams then used the Canadarm2 to take the truss from the shuttle's robotic arm. MacLean is the first Canadian to operate the Canadarm2 in space.[31]

Tanner and Stefanyshyn-Piper began the "camping out" preparations in the Quest Airlock to prepare for a Day 4 spacewalk. The preparations are new pre-breathing measures on the part of NASA, to avoid decompression sickness, or the bends, by getting rid of some nitrogen in their bloodstreams. The preparations involve wearing oxygen masks and sleeping overnight in the airlock with the airlock at under 69 kPa (10 psi), to acclimate their bodies the low pressures they will encounter when wearing their spacesuits.[31]

September 12 (Flight day 4)

[edit]

Following the installation of the P3/P4 Truss to the ISS by the Canadarm2, Tanner and Stefanyshyn-Piper began their spacewalk to activate the truss at 09:17 UTC. During the EVA they installed power and data cables between the P1 & P3/P4 trusses, released the P3/P4 truss' launch restraints and a number of other tasks to configure the truss for upcoming activities. The spacewalk was so successful that the astronauts carried out a number of tasks scheduled for later EVAs, with the eventual completion of the EVA at 15:43 UTC. A bolt, spring and washer assembly from a launch lock was lost during these extra activities and floated off into space.[32]

Following the completion of the EVA, the station's crew began preparing for Day 5's spacewalk, with astronauts Burbank and MacLean entering the Quest Airlock for their "camp out" at 18:40 UTC, ready for the scheduled 09:15 UTC EVA.

September 13 (Flight day 5)

[edit]

On Day 5, the second spacewalk of the mission was conducted, this time by first-time spacewalkers Burbank and MacLean. They devoted the day to the final tasks required for activation of the Solar Alpha Rotary Joint (SARJ). The SARJ is an automobile-sized joint that will allow the station's solar arrays to turn and point toward the sun. Burbank and MacLean released locks that had held the joint secure during its launch to orbit aboard Atlantis. As they worked, the spacewalkers overcame several minor problems, including a malfunctioning helmet camera, a broken socket tool, a stubborn bolt, and a bolt that came loose from the mechanism designed to hold it captive. The stubborn bolt required the force of both spacewalkers to finally remove it.[33][34]

Burbank and MacLean spent 7 hours and 11 minutes outside the station, beginning their spacewalk at 09:05 UTC and completing it at 16:16 UTC. In addition to the SARJ work, they completed several "get-ahead" tasks during their time outside.[33]

Engineers encountered a glitch during the four-hour activation and checkout of SARJ, and had temporarily delayed starting the deployment of the new solar arrays pending further work and checkout of the SARJ. The timeline allowed ample time to continue working on the problem during the night and still complete the deploy of the arrays on Thursday as scheduled.[33][35]

September 14 (Flight day 6)

[edit]

Day 6 continued the installation of the solar array. The unfurling of the solar panels themselves began a little behind schedule due to the problem encountered on Day 5 with SARJ. This problem was determined to be in the software, and a workaround was developed. The unfurling of the panels continued throughout the morning in stages to prevent the panels sticking, as they did during STS-97.[36] It was noted by the crew that some panels were still sticking together, but this didn't cause any problems.[37] Although the installation has been completed, the solar arrays will not provide power to the station until the next shuttle mission, STS-116, scheduled for December 2006, when the station will undergo a major electrical system rewiring.[38]

Other activities of Day 6 included a "double walk off" of the station's Canadarm2 from its current location at the Mobile Base System to the Destiny Laboratory Module[37] and the preparation for the mission's third spacewalk. A number of interviews were also conducted later in the day, between Jett & MacLean and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper & students.

September 15 (Flight day 7)

[edit]

Flight day 7 featured the third and final spacewalk of mission STS-115. The start of the spacewalk was delayed after a circuit-breaker-like remote power controller (RPC) tripped, causing loss of power to the airlock's depressurization pump. This was attributed to a momentary spike in the electric current of the depressurization pump. After assessing data to ensure the system had no short circuit, the breaker was reset and pump reactivated.[39] Joe Tanner and Heide Stefanyshyn-Piper began their spacewalk at 10:00 UTC after a 45-minute delay[40]

During the 6-hour and 42-minute spacewalk, the astronauts carried out numerous maintenance and repair tasks including removal of hardware used to secure the P3/P4 radiator during launch. Ground Flight Controllers subsequently unfurled the radiator, increasing the ability of the station to dissipate heat into space. Also, completed during this spacewalk was the retrieval of a materials exposure experiment from the outside of the ISS, maintenance on the P6 truss, installation of a wireless TV aerial and the replacement of the S1 truss' S-band antenna assembly.

A number of "get-ahead" tasks previously scheduled for future missions were also performed during this spacewalk. Near the end of the spacewalk, the astronauts carried out a test to evaluate using infrared video of the leading edge of Atlantis' wing to detect debris damage.[40]

After the spacewalk, the station's mobile transporter was moved to a worksite on the P3 truss to inspect portions of that truss.

September 16 (Flight day 8)

[edit]Day 8 of STS-115, the last full day with Space Shuttle Atlantis docked to the ISS, was mainly spent in preparation for the undocking procedures to occur in flight day 9. The crew spent the morning resting following their highly successful mission, and then began getting ready for the undocking by carrying out transfers of ISS equipment and science experiments onto Atlantis ready for the trip home.[41]

The crews of Expedition 13 and STS-115 also took part in the traditional joint-crew news conference, with mission Commander Brent Jett commenting on the success of the mission and on the construction missions to follow:

"All of the rest of the assembly missions are going to be challenging. We have similar payloads flying in the future. We are off to a good start on assembly. I think we can pass along a lot of the lessons to the future crews."

September 17 (Flight day 9)

[edit]

Flight day 9 saw the end of STS-115's tasks at the ISS as Atlantis undocked from the International Space Station at 12:50 UTC.

Following the traditional farewell ceremonies between Expedition 13 and STS-115, the hatch between Atlantis and the ISS was closed and locked at 10:27 UTC. Then, after a series of checks for leaks, Atlantis left the dock to begin its 360-degree flyaround of the expanded ISS to document the new configuration.

September 18 (Flight day 10)

[edit]The crew of STS-115 spent the morning of Flight Day 10 carrying out final inspections of Atlantis' heat shield in preparation for re-entry on flight day 12.

Orbiting around 80 kilometers (50 mi) behind the ISS, the crew used the Orbiter's robotic arm and boom sensor system to make sure that no damage had been done to Atlantis' nose and wing leading edges by micrometeoroids and other space junk. The crew spent the rest of this light duty day stowing equipment in preparation for re-entry and landing.

September 19 (Flight day 11)

[edit]

During the morning of day 11, astronauts Jett and Ferguson tested Atlantis' reaction control thrusters and practiced for landing using on-board computers. The thrusters will be used to position the shuttle during re-entry.

The crew also took some time for interviews, with Ferguson telling the media that everyone on board was looking forward to landing. "I think we all, thus far, feel pretty good about the job that we did," Ferguson said. "We are looking forward to a successful re-entry and landing sometime tomorrow."

Following the interviews, the crew continued their preparations for re-entry by stowing unnecessary equipment and other tasks prior to landing. However, the crew informed the Mission Control Center later in the day that, following the test of the reaction control system, an object was seen moving in a co-orbital path with the Orbiter. The astronauts spotted the object using an on-board TV camera, but unfortunately the resolution of the images was not high enough to identify the object.

The images were sent down to the MCC for further analysis by flight controllers, who were concerned about the possibility that the object may have come off Atlantis, and as such wished to identify the object. The most likely scenario was that the object was benign, such as ice or a piece of shimstock (observed earlier in the flight protruding from the heat shield) that may have shaken loose.[42] However, the possibility remained that the object may be of critical importance, such as a tile from the Orbiter's thermal protection system, and the Mission Control Center asked Atlantis' crew to power up the shuttle's robotic arm ready to reinspect the orbiter, and drew up plans for a series of tests which took place on flight day 12 to determine whether the shuttle was safe for re-entry. This extra inspection, added to poor weather forecasts predicted for the Shuttle Landing Facility for Wednesday, and the de-orbit burn and landing were delayed by a day.

September 20 (Flight day 12)

[edit]Following the discovery of a co-orbiting object on flight day 11, Flight Controllers spent the early hours of the morning using the Orbiter's robotic arm to inspect the upper surface of Atlantis, with the astronauts on board the Orbiter spending the rest of the morning scanning the underside of the shuttle for any areas of concern. Following these scans, the crew received word from the Mission Control Center in Houston to use the orbiter boom sensor system to conduct more inspections of Atlantis' heat shield.

Following the review of these scans, together with an overnight analysis of the payload bay by Ground Flight Controllers, it was determined that there remained no safety issue with Atlantis, and Mission Controllers cleared the Orbiter for re-entry. This clean bill of health, added to a favorable weather forecast for the Shuttle Landing Facility for Thursday morning, permitted Atlantis to be cleared for a landing the next day.

The crew spent the remainder of the day in preparation for landing, packing up gear and stowing the Ku band antenna used for TV broadcasts. During the inspection, the crew was notified that the Soyuz TMA-9 spacecraft was docked with the ISS above, which carried the first half of the Expedition 14 crew.

September 21 (Flight day 13 and landing)

[edit]

Flight day 13 was the last day of the mission, with the final re-entry procedures and landing taking place during the morning, and numerous debriefs and conferences in the afternoon. The landing process began hours before the actual landing at Kennedy Space Center. The process began with the APU prestart at 04:37 EDT, followed by the closing of the payload bay doors and sealing of the Orbiter at 04:45 EDT. Atlantis' crew received the final "Go" for the prime re-entry window from Mission Control in Houston at 04:52 EDT. The crew then started the deorbit reorientation of the shuttle so that its engines faced in its direction of travel, meaning that by firing the engines for the deorbit burn Atlantis would slow down and begin its descent out of orbit.

The de-orbit burn was initiated at 05:15 EDT, lasting 2 minutes 40 seconds with two engines burning well throughout. The astronauts aboard the Orbiter were informed at 05:17 EDT that their burn was perfect, with no alterations required as Atlantis began her drop through the atmosphere above the Indian Ocean.

Following the deorbit burn, the crew of Atlantis began dumping excess propellant overboard, a process lasting 3 minutes, concluding at 05:26 EDT, with the Orbiter 55 minutes away from landing. Twenty-five minutes later, at 05:51 EDT, Atlantis began feeling the effects of the atmosphere at an altitude of approximately 130 kilometres (81 mi), and soon after began its "roll reversal banking" in order to bleed off most of the 27,000 kilometres per hour (17,000 mph) she was traveling at, ready for landing at less than 760 kilometres per hour (470 mph). The ISS was positioned in such a way as to be above the reentry path taken by Atlantis, so the astronauts were able to observe the entire maneuver from above.

At 06:08 EDT, the downlink from the Shuttle was acquired by the MILA tracking station on Merritt Island, Florida, with GPS data beginning to be accepted by the Orbiter three minutes later. Ten minutes following the first detection of Atlantis, two sonic booms were heard at Kennedy Space Center as the Orbiter dropped below the sound barrier three minutes prior to touchdown. Commander Jett took control of Atlantis a minute later, and, with Kennedy Space Center Runway 33 in sight, began bringing his ship in for a landing.

Atlantis' main gear touched down at 06:21:30 EDT on Runway 33 at the Space Shuttle Landing Facility at Kennedy Space Center, with the nose gear following 6 seconds later at 06:21:36 EDT, and, 8,000,000 kilometres (5,000,000 mi) after launch, the Orbiter's wheels came to a stop at 06:22:16 EDT, bringing mission STS-115 to an end.

The morning's landing was considered a night landing as it took place about 48 minutes before sunrise, and as such was the 21st night landing for the Space Shuttle Program. It was the 63rd landing at Kennedy Space Center, as well as the 27th mission for Atlantis.

Post flight

[edit]

While working on the Atlantis orbiter, NASA technicians discovered that one of the spacecraft's radiator panels showed evidence of micrometeorite damage.[43] A hole was observed which was reported to be about 2.7 mm (0.108 in) in diameter.[44]

Debris analysis

[edit]NASA's Mission Management Team conducted a detailed analysis of data from many sources including ground imagery, radar, shuttle inspections using the Canadarm and from the space station.[45] By Day 2 they pinpointed a handful of launch debris events, and drew a preliminary conclusion that the effect was minimal.[46] Later that day, NASA agency engineers decided that additional heat shield inspections were not required.[47] The preceding only relates to debris shed immediately during or after launch, and not the debris observed on September 19, 2006.

Not mentioned was a large debris event during launch at 48 seconds near max Q. Because it happened on the ET side opposite the Orbiter, it was never a danger to the Shuttle. By the origin from near the top of the ET, it presents a new source of debris and is therefore of concern for further missions.

Wake-up calls

[edit]A tradition for NASA spaceflights since the days of Gemini, mission crews are played a special musical track at the start of each day in space. Each track is specially chosen, often by their family, and usually has special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[48]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist | Played for | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 |

"Moon River" | Audrey Hepburn | Brent Jett | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 3 |

"cello & double bass" | Daniel Burbank's children | Daniel Burbank | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 4 |

"My Friendly Epistle" | Taras Shevchenko | Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 5 |

"Takin' Care of Business" | Bachman–Turner Overdrive | Steve MacLean | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 6 |

"Wipe Out" | The Surfaris | Chris Ferguson | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 7 |

"Hotel California" | The Eagles | Joseph Tanner | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 8 |

"Twelve Volt Man" | Jimmy Buffett | Daniel Burbank | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 9 |

"Danger Zone" | Kenny Loggins | Chris Ferguson | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 10 |

"Rocky Mountain High" | John Denver | Joseph Tanner | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 11 |

"Ne Partez Pas Sans Moi" | Celine Dion | Steve MacLean | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 12 |

"Beautiful Day" | U2 | Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper | wav mp3 Transcript |

| Day 13 |

"WWOZ" | Better Than Ezra | Brent Jett | wav mp3 Transcript |

Contingency mission

[edit]STS-300 was the designation given to the Contingency Shuttle Crew Support mission which would have launched in the event Space Shuttle Discovery became disabled during STS-114 or STS-121. This rescue mission would have been a modified version of the STS-115 mission with the launch date being brought forward and the crew reduced.

STS-300 would have launched no earlier than August 17, 2006, and the crew for STS-300 would have been a four-person subset of the full STS-115 crew:[49]

- Brent Jett, commander

- Christopher Ferguson, pilot and backup Remote Manipulator System (RMS) operator

- Joseph Tanner, mission specialist 1, Extravehicular 1 and prime RMS operator

- Daniel Burbank, mission specialist 2 and Extravehicular 2

Media

[edit]-

The components and the unfolding of the P3/P4 Truss in Detail (Animation).

-

Space Shuttle Atlantis launches from launch pad 39B at Kennedy Space Center as part of the STS-115 mission.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ "Spaceflight mission report: STS-115".

- ^ "Spaceflight mission report: STS-115".

- ^ a b Harwood, William (2006). "STS-115 Quick-Look Mission Data". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ "Mike Leinbach, STS-115 Launch Director, NASA Direct interview". NASA News. August 22, 2006. Archived from the original on January 30, 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ Wilkes, Jim (September 13, 2006). "Shuttle crew puts designers on cloud 9". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on March 24, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2006.

- ^ "STS-115". Spacefacts. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ Harwood, William. "CBS News Space Place – STS-115 Status Report". CBS News. Archived from the original on May 26, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2006.

- ^ Post Mission Management Team (MMT) press briefing, following STS-121, on July 16, 2006

- ^ "Florida Today – The Flame Trench". Florida Today. Archived from the original on March 31, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ "Dress rehearsal Thursday for Atlantis". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved August 11, 2006.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Foam still a key concern for shuttle launch". New Scientist SPACE. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved August 13, 2006.

- ^ "Shuttle communications antenna bolts a concern". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2006.

- ^ "NASA to Replace Antenna Bolts on Shuttle Atlantis". Space.com. August 18, 2006. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved August 19, 2006.

- ^ "Lightning delays Atlantis launch a day". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on August 31, 2006. Retrieved August 26, 2006.

- ^ "Shuttle launch delayed until Monday". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). August 26, 2006. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved August 27, 2006.

- ^ "NASA scrubs Atlantis launch under storm threat". CNN. Archived from the original on August 31, 2006. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- ^ "Rollback options assessed". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved August 27, 2006.

- ^ "Atlantis' status is at weather's mercy". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved August 28, 2006.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Atlantis going back to the pad". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 3, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2006.

- ^ "NASA aims for Wednesday launch". CNN. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- ^ "Shuttle launch window extended to 8 September". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- ^ "Atlantis launch scrubbed". Spaceflight Now. September 6, 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2006.

- ^ "Atlantis launch slips to Friday at the earliest". Spaceflight Now. September 6, 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2006.

- ^ "Engine cutoff sensor options debated". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- ^ "Further delay for space shuttle". BBC News. September 8, 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- ^ "Suspect sensor stays 'wet' after tank drained". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- ^ Harwood, William (September 8, 2006). "Update: Launch delayed by ECO sensor failure; Hale says team made right decision". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2025.

- ^ "Shuttle enters space after 'majestic launch'". CNN. September 9, 2006. Archived from the original on September 16, 2006.

- ^ a b c d "STS-115 MCC Status Report #01". NASA. September 9, 2006. Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2006.

- ^ a b c "STS-115 MCC Status Report #03". NASA. September 10, 2006. Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "STS-115 MCC Status Report #05". NASA. September 11, 2006. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ "MCC Status report #07". NASA. September 12, 2006. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ a b c "STS-115 MCC Status Report #09". NASA. September 13, 2006. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ^ "STS-115: Second EVA Successfully Completed". space.gs. September 13, 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2006. [dead link]

- ^ "Initial solar array deploy held up for troubleshooting". SpaceFlightNow. September 13, 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ^ "Second space station solar array wing deployed". SpaceFlightNow. December 4, 2000. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- ^ a b "STS-115 MCC Status Report #11". NASA. September 14, 2006. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ^ "Space station spreads its new power wings". September 14, 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- ^ "STS-115 MCC Status Report #12". NASA. September 15, 2006. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- ^ a b "STS-115 MCC Status Report #13". NASA. September 15, 2006. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- ^ "STS-115 MCC Status Report #15". NASA. September 16, 2006. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ^ "Heat shield cleared; Shannon talks night launches, Hubble". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 10, 2007.

- ^ Shuttles to resume nighttime launches; Atlantis damaged Archived October 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Spaceflight Now, 06/10/06

- ^ James Oberg (2006). "NASA studying a 'ding' on shuttle". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ "NASA has 'high confidence' Atlantis in good shape". SpaceFlightNow. September 10, 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ "Debris analysis update". SpaceFlightNow. September 11, 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ "Additional heat shield inspections ruled out". SpaceFlightNow. September 11, 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ Fries, Colin (July 18, 2006). "Chronology of Wakeup calls" (PDF). NASA. p. 57. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2010. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ^ "STS-121 Nasa Press Kit" Archived July 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine NASA Press Kit – STS-121, May 2006.

External links

[edit]- STS-115 Official NASA Page

- STS-115 Multimedia Gallery – Images and videos. Archived November 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- NASA's Space Shuttle site with frequent news updates.

- SpaceFlightNow blog

- Space-Astronautics.com

- Canadian Space Agency: Missions overview, updates, timeline, and gallery

- SpaceflightWeb Mission Profile

- Spacefacts.de

Videos

[edit]- Mission Timeline – Canadian Space Agency: with animations of key parts of the mission

- STS-115 Video Highlights Archived December 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

STS-115

View on GrokipediaCrew

Crew Members

The STS-115 crew comprised six astronauts from NASA and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), tasked with delivering and installing the P3/P4 integrated truss segment and solar arrays to the International Space Station (ISS). Commander Brent W. Jett Jr. led the mission, marking his fourth spaceflight and third as commander aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis.[3] Brent W. Jett Jr. (NASA), aged 47, served as commander, overseeing all mission operations including ascent, rendezvous, and entry. A U.S. Navy captain from Pontiac, Michigan, he earned a B.S. in aerospace engineering from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1981 and an M.S. in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1989. Selected as a NASA astronaut in 1992, Jett had previously commanded STS-97 (2000), during which he delivered the first set of solar arrays to the ISS, and piloted STS-72 (1996) and STS-81 (1997). His naval career included over 5,000 flight hours as an F-14 Tomcat pilot.[3] Christopher J. Ferguson (NASA), aged 45, acted as pilot, responsible for primary ascent and entry piloting duties. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he held a B.S. in mechanical engineering from Drexel University (1984) and an M.S. in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School (1991). Selected in 1998, this was his first spaceflight; Ferguson later commanded STS-126 (2008) and STS-135 (2011). A retired U.S. Navy captain, he logged over 5,700 flight hours in more than 30 aircraft types, including as a TOPGUN instructor.[4] The mission specialists included Joseph R. Tanner (NASA), aged 56, who served as lead spacewalker with extensive extravehicular activity (EVA) experience. From Danville, Illinois, Tanner obtained a B.S. in mechanical engineering from the University of Illinois in 1973. Selected in 1992, this was his fourth flight; prior missions included STS-66 (1994, atmospheric research), STS-82 (1997, Hubble Space Telescope servicing with two EVAs), and STS-97 (2000, ISS solar array installation with three EVAs). A former U.S. Navy pilot and NASA research pilot, he accumulated over 8,900 flight hours.[5] Heidemarie M. Stefanyshyn-Piper (NASA), aged 43, handled robotics operations and EVA support on her first spaceflight. Born in St. Paul, Minnesota, she received both B.S. and M.S. degrees in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1984 and 1985, respectively. Selected in 1996, Stefanyshyn-Piper was a U.S. Navy lieutenant commander with expertise in salvage diving and surface warfare. She later flew STS-126 (2008), logging over 27 days in space across two missions.[6] Daniel C. Burbank (NASA), aged 45, provided EVA and robotics support on his second flight. A native of Tolland, Connecticut, he earned a B.S. in electrical engineering from the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in 1985 and an M.S. in aeronautical science from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in 1990. Selected in 1996, Burbank's prior mission was STS-106 (2000), which delivered supplies to the ISS. As a U.S. Coast Guard captain, he flew over 4,000 hours on more than 2,000 missions, including search and rescue operations.[7] Steven G. MacLean (CSA), aged 51, operated the Canadarm2 robotic arm and performed an EVA on the ISS, becoming the second Canadian to do so. From Ottawa, Ontario, he held a B.Sc. (honors) and Ph.D. in physics from York University. Selected by the CSA in 1983 as one of Canada's first six astronauts, this was his second spaceflight; his debut was STS-52 (1992) as a payload specialist conducting microgravity experiments. A laser physicist and former university lecturer, MacLean later served as CSA president from 2008 to 2013.[8]Crew Notes

The STS-115 crew exemplified international collaboration in the Space Shuttle program, featuring one astronaut from the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) among a primarily NASA-composed team of six. Steven G. MacLean, representing Canada, contributed to the mission's objectives aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis, underscoring the partnership between NASA and international partners in International Space Station (ISS) assembly.[1][9] A key milestone for the crew was MacLean's role as the first Canadian astronaut to operate the Canadarm2 robotic arm on the ISS, which he manipulated nearly daily to support the installation of the P3 and P4 truss segments. Additionally, MacLean became the second Canadian to perform an extravehicular activity (EVA), joining Daniel C. Burbank—who was also on his first spacewalk—for EVA-3 to deploy a radiator and stow protective equipment. These achievements highlighted Canada's technological contributions to the ISS through the Mobile Servicing System.[10][1][11] The crew's composition also reflected diversity in experience levels, marking the first Space Shuttle mission to include two rookie astronauts in prominent roles: pilot Christopher J. Ferguson on his inaugural flight and mission specialist Heidemarie M. Stefanyshyn-Piper on hers. This blend of novices with veterans like commander Brent W. Jett Jr. (on his fourth flight) and mission specialist Joseph R. Tanner (on his fourth) ensured robust operational support while providing opportunities for emerging talent.[1][12]Mission Overview

Primary Objectives

The primary objectives of STS-115 centered on resuming the assembly of the International Space Station (ISS) after a hiatus following the Columbia disaster in 2003, by delivering and installing the P3/P4 integrated truss segment on the port side of the station's main structure.[1] This 35,000-pound (17.5 short tons) segment, which included the S4 truss element with photovoltaic radiator assemblies, was attached to the existing P1 truss using the shuttle's robotic arm and the ISS's Canadarm2, marking the first major structural addition to the outpost in nearly four years.[2][1] A key component of the installation involved deploying the S4 solar arrays, comprising the 2A and 4A panels, each spanning 115 feet and collectively generating up to 66 kilowatts of power to help restore the ISS's full electrical capacity for future operations and crew support.[13][1] The mission also required three extravehicular activities (EVAs) totaling over 20 hours to connect power and data cables, release launch restraints, and activate the new hardware, ensuring the truss and arrays were fully operational.[1] The overall mission was planned for 12 days, encompassing 188 orbits at an altitude of approximately 220 statute miles and covering about 4.9 million statute miles.[1] Secondary objectives included supporting ongoing ISS Expedition 13 activities through joint operations and crew handover procedures, as well as conducting microgravity experiments such as the Commercial Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus (CGBA) to study microbial behavior in space.[1][14]Spacecraft Configuration

Space Shuttle Atlantis (OV-104), embarking on its 27th mission, formed the core of the STS-115 vehicle stack, integrated with the Super Light Weight External Tank ET-118 and Reusable Solid Rocket Motor (RSRM) set 94, along with Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) set BI-127. ET-118, measuring 154 feet in length and 27.6 feet in diameter, carried approximately 1.6 million pounds of cryogenic propellants—liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen—providing the primary fuel for the orbiter's main engines during ascent. The RSRMs delivered about 3.3 million pounds of thrust per booster at ignition, accounting for roughly 83% of the stack's initial liftoff thrust, while the SRBs themselves weighed over 1.3 million pounds each when fully loaded. This configuration marked the first use of an external tank with post-Columbia foam reduction modifications, including redesigned bipod ramp and liquid hydrogen protuberance air duct foam application techniques to minimize debris risks.[15] In response to the STS-107 Columbia disaster, which highlighted vulnerabilities in the orbiter's thermal protection system, Atlantis's wing leading edge reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) panels—22 per wing, each up to 7 feet long—were subjected to rigorous pre-launch inspections using thermography, ultrasound, and visual methods at NASA's Kennedy Space Center. No significant structural modifications were implemented on Atlantis for this flight, but the vehicle benefited from program-wide enhancements such as improved gap filler protrusion limits and non-destructive evaluation techniques to ensure panel integrity. On-orbit, these panels received focused attention during focused inspections to detect any ascent-induced damage.[16] The crew compartment accommodated six astronauts in a standard shuttle layout, with Commander Brent Jett and Pilot Christopher Ferguson occupying the forward flight deck seats (positions 1 and 2) for launch and entry control. Mission Specialists Joseph Tanner, Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper, Daniel Burbank, and Steven MacLean were assigned to seats 3 through 6, primarily on the mid-deck for launch but with provisions for payload bay access via the airlock and payload specialist roles during extravehicular activities and robotics operations. This arrangement optimized visibility for the flight crew during ascent and reentry while allowing specialists flexibility for in-orbit tasks, including truss handling and station outfitting.[17] Critical avionics and support systems tailored for STS-115 included the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS), a 50-foot articulated arm extension for the shuttle's remote manipulator system, outfitted with an intensified 800-mm camera, digital sensors, and laser scanners to perform detailed thermal protection system surveys. The OBSS enabled late inspection (LIS) scans of the wing leading edges, nose cap, and belly tiles on flight day 2, capturing high-resolution imagery at angles like 145 and 230 degrees during backflip maneuvers relative to the International Space Station. Complementing this, the Ku-band antenna, a 0.9-meter dish mounted in the payload bay, supported high-rate data links up to 6 Mbps for video transmissions and proximity communications with the ISS, ensuring real-time coordination during rendezvous and docking phases. A thermal shroud was added pre-launch to mitigate overheating risks during station-oriented attitudes.[15][1]Payload Details

The primary payload for STS-115 was the P3/P4 integrated truss segment, a critical component for expanding the International Space Station's power infrastructure. Measuring approximately 45 feet in length and weighing 35,000 pounds, the truss consisted of the P3 and P4 structural elements, which housed advanced systems for energy generation and management.[2][18] This payload incorporated photovoltaic arrays (solar wings 2A and 4A) capable of generating up to 66 kilowatts of power, along with associated nickel-hydrogen batteries for energy storage during orbital night periods, and electronics for power conditioning and distribution.[1] A photovoltaic thermal radiator was integrated into the P3 segment to dissipate excess heat from the solar arrays and batteries, ensuring thermal stability in the vacuum of space.[1] These components collectively enabled the ISS to nearly double its electrical output upon installation.[2] Secondary payloads on the mission included the Materials International Space Station Experiment-5 (MISSE-5), a passive experiment exposing over 200 material samples to the space environment to study degradation from atomic oxygen, ultraviolet radiation, and micrometeoroids; it was retrieved during the third spacewalk and returned to Earth for analysis.[19] The Commercial Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus (CGBA), a multi-user incubator and refrigerator system, supported biological and materials science experiments by maintaining precise temperature and environmental controls for samples like plant cells and protein crystals. Additionally, solar monitoring capabilities were provided through the photovoltaic arrays and associated instrumentation on the truss, allowing real-time observation of solar energy capture and system performance.[1] Crew seating was configured to optimize mission operations, with Mission Specialists Joseph Tanner and Daniel Burbank assigned to the mid-deck seats to allow focused preparation for extravehicular activities, while Steven MacLean was positioned adjacent to the robotics workstation on the flight deck for oversight of payload handling.[17] The P3/P4 truss was meticulously integrated into Atlantis's payload bay at Kennedy Space Center, where it was mounted on non-deployable pallets and secured with frangible launch locks and vibration-dampening restraints to protect against the high dynamic loads and acoustic environment during ascent.[20] This configuration ensured the truss's structural integrity from ground processing through orbital insertion. The truss installation process, involving robotic arm extraction and attachment to the existing station structure, was successfully executed later in the mission.[1]Preparation and Background

Historical Context

The Space Shuttle mission STS-115 marked the resumption of major International Space Station (ISS) assembly operations following the Columbia disaster on February 1, 2003, which grounded the fleet for over two years and prompted extensive safety reviews and modifications to the shuttle program.[1] Originally scheduled for launch in April 2003 as the 12A assembly flight, STS-115 became the first dedicated ISS construction mission after the return-to-flight test flights STS-114 in July 2005 and STS-121 in July 2006, ultimately lifting off on September 9, 2006, after a three-year delay.[21] This hiatus reflected NASA's prioritization of resolving thermal protection system vulnerabilities, including redesigned external tank foam shedding risks identified during STS-114.[22] The mission's timeline was further extended by rigorous return-to-flight certifications, which required implementation of the 29 recommendations of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, including the 15 Space Shuttle Program "Raise the Bar" initiatives and over 116 hardware modifications.[22] Additionally, Hurricane Katrina in August 2005 severely damaged key NASA facilities along the Gulf Coast, such as the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans—where external fuel tanks were produced—and Stennis Space Center in Mississippi, leading to workforce disruptions and repair efforts that contributed to an additional two-month delay in shuttle operations.[23] Ongoing safety reviews also prolonged the preparation phase, ensuring compliance with updated program standards before resuming assembly flights.[24] STS-115 arrived at the ISS shortly after the arrival of Expedition 13 crew members in March 2006, providing critical support to the station's ongoing operations during a period of limited construction activity.[25] The mission delivered and installed the P3/P4 integrated truss segments on the port side, along with solar arrays 2A and 4A, to expand the station's power generation capacity to approximately 66 kilowatts and establish redundancy in the electrical systems for future modules and experiments.[1] This addition was essential for balancing the ISS's power distribution, following the earlier installation of starboard-side elements, and enabling sustained crew habitation and research capabilities.[26]Launch Preparations

The Space Shuttle Atlantis, configured for STS-115, was rolled out from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Pad 39B on July 31, 2006, following the integration of the P3/P4 Integrated Truss Segment and solar arrays into the payload bay at the Orbiter Processing Facility.[27] This rollout marked the completion of major vehicle assembly, including attachment of the external tank ET-119 and solid rocket boosters, with subsequent payload hazard tests and interface verifications conducted at the pad to ensure compatibility with International Space Station operations.[1] On August 25, 2006, a lightning strike hit the lightning protection system at Pad 39B, registering approximately 100,000 amperes and becoming one of the strongest recorded at a shuttle launch site; no visible damage occurred to the vehicle, but the incident prompted a three-day countdown scrub for extensive inspections of electrical systems, pyrotechnic devices, and ground support equipment.[27][28] Engineers performed health checks on 17 pyrotechnic initiator controllers, resolving concerns through alternative thermocouple data analysis from the solid rocket boosters, allowing resumption of processing without a full 96-hour integrity test.[28] The Flight Readiness Review, convened on August 15-16, 2006, at Kennedy Space Center, approved the mission for launch no earlier than August 27, 2006, after confirming vehicle readiness and addressing minor issues like a communications antenna bolt replacement.[27][29] However, Tropical Storm Ernesto's approach to Florida on August 29 necessitated a partial rollback of Atlantis toward the Vehicle Assembly Building for protection, which was halted and reversed once the storm weakened offshore, delaying the countdown further and shifting the target launch to September 6.[27][1] Replenishment of cryogenic propellants began on August 16 to support launch-day fueling simulations, with a full tanking test successfully demonstrating external tank sensor performance closer to the revised date.[27][30] The STS-115 crew arrived at Kennedy Space Center on August 7, 2006, for final training, including a Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test on August 10 that simulated launch-day procedures, suit donning, and emergency egress.[31] Quarantine protocols commenced on September 2, 2006, in preparation for the adjusted September 6 launch attempt, which was scrubbed 24 hours prior due to a fuel cell issue identified during pre-tanking checks.[27][1] The crew entered quarantine isolation again and completed suit-up on September 9, 2006, boarding Atlantis for the successful liftoff later that day.[27]Launch and Ascent

Launch Attempts

The launch of Space Shuttle Atlantis on mission STS-115 faced a final delay during its countdown on September 8, 2006, when the attempt was scrubbed approximately nine minutes prior to the planned 11:15 a.m. EDT liftoff due to a faulty reading from one of the engine cut-off sensors in the external tank.[1] This issue required further analysis to ensure the integrity of the fuel system, prompting NASA to postpone the launch by 24 hours.[1] The subsequent attempt on September 9, 2006, proceeded without further holds, achieving liftoff at 11:15 a.m. EDT (15:15 UTC) from Launch Pad 39B at Kennedy Space Center.[1] Solid rocket booster ignition and external tank separation occurred nominally, marking a clean ascent phase for the mission.[1] Atlantis reached a 51.6° orbital inclination to rendezvous with the International Space Station, aligning with the station's operational path.[32]Liftoff and Orbital Insertion

Space Shuttle Atlantis lifted off successfully on September 9, 2006, at 11:14:55 a.m. EDT from Launch Pad 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center, marking the resumption of International Space Station assembly missions.[33] The ascent began with ignition of the two solid rocket boosters and three space shuttle main engines (SSMEs), which throttled up to 104.5% thrust immediately after liftoff. Approximately one minute into flight, the engines throttled down to 72% to pass through maximum dynamic pressure (Max-Q), before ramping back up; the boosters separated at T+2:06.[33] Main engine cutoff (MECO) occurred at T+8:26, with Atlantis reaching an altitude of approximately 104 nautical miles (193 kilometers), placing it on a suborbital trajectory. External tank (ET) separation followed at T+8:45, after which the tank re-entered the atmosphere and disintegrated over the Indian Ocean. No significant anomalies affected the ascent phase, though minor issues like auxiliary power unit accelerometer dropouts were noted but did not impact performance.[33] Orbital insertion was achieved through firings of the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines. An initial OMS assist burn occurred shortly after ET separation, followed by the primary OMS-2 burn at approximately T+37:20 for 144 seconds, raising the orbit to 124 by 154 nautical miles (230 by 285 kilometers). A subsequent non-crew OMS burn further circularized the orbit toward 220 nautical miles (407 kilometers) to support rendezvous with the ISS.[33] Flight Day 1 activities focused on stabilizing the vehicle in orbit and preparing for subsequent operations, including reconfiguration of the payload bay. The crew opened the payload bay doors at T+2:26 and activated the remote manipulator system (RMS) by T+3:36, positioning it for later use; initial onboard camera checks of the thermal protection system confirmed no visible damage to critical areas. Detailed inspections of the wing leading edges and nose cap using the orbiter boom sensor system (OBSS) began on Flight Day 2 and reported no anomalies.[33]On-Orbit Operations

Rendezvous and Docking

The rendezvous and docking operations for STS-115 took place on Flight Day 3, September 11, 2006, marking the resumption of International Space Station (ISS) assembly after a four-year hiatus. Space Shuttle Atlantis executed four Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) burns over the previous days to gradually close the distance to the ISS, positioning the orbiter approximately 9.5 miles behind the station by the start of the terminal phase.[17] These burns included two mid-course corrections on Flight Day 2 and the Terminal Initiation (TI) burn about 2.5 hours prior to docking, which placed Atlantis 50,000 feet behind the ISS along the R-Bar approach corridor.[1] The maneuvers ensured precise alignment for the automated docking sequence to the Pressurized Mating Adapter-2 (PMA-2) on the forward port of the Destiny laboratory module.[1] As part of the rendezvous profile, Commander Brent Jett piloted Atlantis through the R-Bar Pitch Maneuver (RPCM), a 360-degree backflip initiated at approximately 600 feet below the ISS and lasting about nine minutes. This maneuver allowed the Expedition 13 crew to capture high-resolution photographs of Atlantis's thermal protection system using digital cameras, aiding in post-flight damage assessments.[1] At 10:48:27 UTC, Atlantis achieved hard dock with PMA-2, with the docking mechanism hooks and latches securing the connection; the shuttle's steering jets were then deactivated to minimize structural loads on the interface.[17] The hatches between Atlantis and the ISS were opened at 12:13 UTC, enabling the STS-115 crew to float into the station where they were greeted by Expedition 13 Commander Pavel Vinogradov, Flight Engineer Jeff Williams, and Flight Engineer Thomas Reiter.[17] Initial joint activities focused on verifying the integrity of the docking seals and conducting a brief crew handover overview, with preparations beginning for the transfer of the P3/P4 Integrated Truss Segment via the Pressurized Mating Adapter interface.[34] This included coordination between the shuttle and station crews for robotic arm handoff procedures to support subsequent ISS integration tasks.[1]Spacewalks

The STS-115 mission featured three extravehicular activities (EVAs) conducted by crew members to facilitate the integration of the P3/P4 integrated truss structure with the International Space Station, including electrical connections, restraint releases, and preparatory configurations for solar array operations. These spacewalks, performed from the Quest airlock, totaled 20 hours and 19 minutes and marked the resumption of major ISS assembly tasks after a four-year hiatus.[1][35] The first EVA occurred on September 12, 2006 (flight day 4), with mission specialists Joseph R. Tanner and Heidemarie M. Stefanyshyn-Piper serving as the spacewalkers for a duration of 6 hours and 26 minutes. Following the robotic handover and attachment of the P3/P4 truss to the P1 segment earlier in the mission, Tanner and Piper focused on utility transfers and preparations, connecting power and data cables between the new truss and the station, releasing launch locks and restraints on the solar array blanket boxes and beta gimbal assemblies, configuring the solar alpha rotary joint for rotation, and removing circuit interrupt devices to enable power flow. A small hardware loss occurred when a bolt and washer detached and floated away during the removal of a protective cover on the truss.[1][35] On September 13, 2006 (flight day 5), Daniel C. Burbank and Steven G. MacLean conducted the second EVA, lasting 7 hours and 11 minutes. Their main objectives involved finalizing truss attachment preparations by releasing multiple locks and pins on the solar alpha rotary joint to allow the mechanism to rotate freely and support subsequent solar array positioning, along with verifying utility connections and stowing tools. The spacewalk faced minor equipment issues, including a helmet camera failure, a broken socket on a pistol-grip tool, and difficulty loosening a particularly stubborn bolt, which extended the timeline but did not prevent task completion.[1][35] The third EVA took place on September 15, 2006 (flight day 7), again with Tanner and Piper outside for 6 hours and 42 minutes. After the successful robotic deployment of the P4 solar array wings on the previous day, the duo powered up and verified the operation of a new cooling radiator on the P3 truss to enhance the station's thermal management system, replaced a degraded S-band communications antenna on the P6 truss, installed protective insulation blankets on various components, and captured infrared imagery of Atlantis's wings to inspect for potential launch debris impacts. This spacewalk addressed get-ahead maintenance tasks to ensure overall system reliability.[1][35]Truss Assembly and Activation

The installation of the P3/P4 integrated truss segment during STS-115 marked a key step in resuming International Space Station assembly after a four-year hiatus. The 17.5-ton, 45-foot-long truss, carrying solar arrays and batteries, was unberthed from Atlantis' payload bay by the shuttle's remote manipulator system (RMS), operated by astronauts Christopher Ferguson and Daniel Burbank. This positioned the truss for handover to the ISS's Canadarm2, controlled by Canadian Space Agency astronaut Steve MacLean and NASA astronaut Jeff Williams from inside the Destiny laboratory. MacLean became the first Canadian to operate Canadarm2 for an official task, executing a "double walk-off" maneuver from the Mobile Base System to the lab to secure the truss for attachment to the existing P1 segment.[1][36][9] Following the spacewalks that bolted the truss in place, robotic operations continued to support final positioning and preparation for solar array deployment. The handover and initial truss positioning on September 12, 2006 (Flight Day 4), ensured precise alignment, setting the stage for system activation while accounting for future modules like Japan's Kibo laboratory. The assembly process, aided briefly by extravehicular activities to connect utilities and remove launch restraints, integrated the P3/P4 seamlessly into the ISS port-side truss.[1][36] On September 14, 2006 (Flight Day 6), the crew initiated deployment of the 2A and 4A solar arrays mounted on the P3/P4 truss, unfurling the 240-foot wingspan structures in a controlled sequence that concluded at 8:44 a.m. EDT. During deployment of the 4A array, a stiction issue caused some panels to stick initially, preventing full extension; this was resolved through ground-directed troubleshooting and crew monitoring, allowing complete unfurling. The arrays, designed to generate up to 66 kilowatts of power, underwent tensioning of the 4A array to maintain rigidity, with initial operations powered by the station's existing systems. Activation followed, including tests of the solar alpha rotary joint to enable array tracking of the Sun and engagement of drive-lock assemblies, where a glitch in the second lock was resolved overnight to ensure full functionality. Power channel verification confirmed connectivity, and the new batteries began charging from the arrays' output, though full integration into the station's power grid was deferred to STS-116. A minor issue arose with the retraction of a temporary radiator on the P4 truss during initial testing, but it was resolved through ground-commanded procedures, allowing deployment of the primary photovoltaic radiator during the third spacewalk on September 15. This completed the truss activation, extending the ISS port truss configuration and doubling the station's power capacity to support ongoing expansion. The updated structure enhanced the overall truss length on the port side, contributing to the ISS's growing framework of approximately 180 feet in that segment.[1][36]Undocking and Re-Entry

Undocking Procedures

On September 17, 2006, during Flight Day 9 of the STS-115 mission, the Space Shuttle Atlantis began undocking procedures from the International Space Station (ISS) after completing assembly tasks and joint operations with the Expedition 13 crew.[33] The process initiated with the opening of docking hooks and latches at approximately 12:47 UTC, following power-up of undocking systems earlier that morning.[33] Undocking occurred at 12:50 UTC, with springs providing the initial separation impulse as the shuttle's steering jets remained off until a safe distance of about 2 feet was achieved.[33][17] Following undocking, Pilot Christopher J. Ferguson executed two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) firings to increase separation: the first at 13:59 UTC with a velocity change of 5.6 feet per second, and the second at 14:27 UTC with 1.0 foot per second, establishing a distance of roughly 400 feet from the ISS.[33] Atlantis then performed a flyaround maneuver, circling the station at various altitudes up to 450 feet to capture high-resolution photography of the newly installed P3/P4 truss segments and overall ISS configuration for post-mission analysis.[33][17] Prior to separation, the combined 13-member crew—seven from STS-115 and six from Expedition 13—gathered for a farewell ceremony and posed for a group photograph inside the station, marking the conclusion of their joint activities.[1] As part of payload bay closeout preparations during the undocking phase, the crew stowed the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) inspection boom in Atlantis's payload bay to secure it for the return journey, a task completed shortly after the flyaround.[33] Additionally, the Materials International Space Station Experiment (MISSE) 5 payload, retrieved earlier during the third spacewalk, was secured in the payload bay during final closeout activities to ensure its safe return to Earth.[33] These steps confirmed the truss installation's structural integrity before Atlantis departed the vicinity.[33]Re-Entry and Landing

The deorbit burn for STS-115 occurred on September 21, 2006 (mission elapsed time 11 days 17 hours 59 minutes), initiating at 09:14:23 UTC and lasting 161.4 seconds using both Orbital Maneuvering System engines, achieving a delta-v of 308.1 ft/s and lowering Atlantis's orbit from 183 by 122 nautical miles to 192.2 by 23.6 nautical miles, targeting a perigee of approximately 300,000 feet for atmospheric entry.[33] This maneuver, performed following a one-day extension for thermal protection system inspections, set the stage for re-entry after undocking from the International Space Station.[1] Atmospheric entry began at entry interface on September 21, 2006, at 09:49:44 UTC (mission elapsed time 11 days 18 hours 34 minutes), when Atlantis crossed 400,000 feet altitude at approximately Mach 25 (about 17,500 mph).[33] Peak heating during the hypersonic phase reached around 3,000°F on the orbiter's leading edges and thermal tiles, with the vehicle maintaining a stable angle of attack and experiencing peak deceleration of about 2.5 g-forces. The trajectory proceeded nominally through the Terminal Area Energy Management (TAEM) interface at 10,000 feet altitude around 10:14:52 UTC, transitioning to powered flight for final approach.[33] Atlantis touched down on Kennedy Space Center Runway 33 at 10:21:30 UTC (mission elapsed time 11 days 19 hours 6 minutes 35 seconds), with main gear touchdown at 10:21:25 UTC at 188.8 knots equivalent airspeed and a sink rate of 1.29 ft/s, followed by nose gear touchdown at 10:21:32 UTC.[1][33] The rollout covered 10,500 feet in 46 seconds under light crosswinds of 8 knots, ending with wheel stop at 10:22:16 UTC and no significant deviations or tilts.[1] Post-landing, the crew safely egressed the vehicle after auxiliary power unit shutdown at approximately 10:39 UTC, with the mission concluding without re-entry anomalies after traveling 4.9 million statute miles.[33][1]Post-Mission Analysis

Flight Performance Review

The STS-115 mission, flown by Space Shuttle Atlantis, achieved full success in its primary objectives, completing a duration of 11 days, 19 hours, 6 minutes, and 35 seconds while traversing 187 orbits around Earth. This performance marked the resumption of International Space Station (ISS) assembly after a four-year hiatus following the Columbia accident, with the crew successfully delivering and installing the P3/P4 integrated truss structure, including associated solar arrays and batteries. All mission goals were met at 100%, enhancing the station's structural integrity and electrical systems without significant delays impacting the timeline.[1][39] A key achievement was the addition of 66 kW of power generation capability through the deployment and activation of the new solar array wings on the P4 truss segment, which added substantial photovoltaic capacity to the U.S. segment and supported future expansion. The solar arrays, once unfurled, began generating power immediately, though full integration into the station's electrical system awaited the subsequent STS-116 mission. This upgrade doubled the potential available power from previous configurations once activated, enabling increased scientific operations and crew accommodations on the ISS. Minor technical hiccups, such as the "stiction" problem during the deployment of one solar array wing—resolved through ground-directed troubleshooting—did not compromise overall functionality. Additionally, a Ku-band antenna glitch caused intermittent communication disruptions but was addressed through onboard troubleshooting, ensuring data relay continued effectively.[1][13][39] Crew health remained robust throughout the flight, with no major medical incidents reported and all astronauts returning in excellent condition. Radiation exposure for the seven-member crew totaled 12.5 mSv, well within NASA's operational limits for short-duration missions and comparable to background levels encountered on prior shuttle flights to the ISS. Post-flight evaluations confirmed nominal physiological responses, underscoring the mission's safety profile despite the inherent risks of spaceflight.[1][39]| Key Performance Metric | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mission Duration | 11 days, 19h 6m 35s | From launch on September 9, 2006, to landing on September 21, 2006 |

| Orbits Completed | 187 | Inclination: 51.6°; Distance: approximately 4.9 million statute miles |

| Objectives Success Rate | 100% | All primary and secondary goals achieved, including truss installation and EVAs |

| ISS Power Restoration | 66 kW | Via P4 solar arrays; added capacity to U.S. segment post-installation, fully integrated during STS-116 |

| Radiation Exposure | 12.5 mSv | Crew average; no adverse effects observed |

Debris and Safety Assessment

Post-flight analysis of the Space Shuttle Atlantis following STS-115 revealed significant micrometeoroid and orbital debris (MMOD) damage to one of its payload bay door radiator panels. Specifically, the right-hand panel #4 (RH4) exhibited an entry hole measuring 3.2 mm by 2.7 mm in the 0.28 mm thick aluminum face sheet, with associated damage including approximately 20 affected honeycomb cells, a 0.79 mm hole in the rear face sheet, a 5.1 mm bulge, and a 6.8 mm crack. Scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) analysis identified the impacting material as fiberglass circuit board fragments, confirming it as orbital debris rather than shuttle-generated. No penetration reached the underlying coolant tubes, thanks to protective aluminum doublers, ensuring no impact on thermal control systems.[40][41] To assess the incident, NASA conducted hypervelocity impact tests at the Johnson Space Center's Hypervelocity Impact Test Facility, replicating the damage using a 1.25 mm diameter projectile of similar composition (glass fiber composite) at 4.14 km/s and a 45-degree angle of incidence. The test (HITF07017) closely matched the observed crater morphology, honeycomb disruption, and rear sheet deformation, validating models of debris cloud formation and penetration thresholds for shuttle radiator designs. These tests confirmed the radiator's shielding effectiveness against particles up to approximately 1 cm in diameter under typical orbital velocities, as the structure's multi-layer aluminum facesheets and core absorbed and dispersed the energy without compromising crew safety or mission-critical functions. The analysis estimated a 1.6% probability (1 in 62) of such an impact on shuttle radiators during a standard ISS mission, contributing to broader orbital debris risk assessments.[40][41][42] External Tank (ET) debris characterization was also performed post-mission, focusing on ice/frost ramp shedding observed during ascent imagery review, with no evidence of impacts to the orbiter's thermal protection system. This aligned with enhanced post-Columbia protocols for debris monitoring, though no orbiter damage was attributed to ET sources.[22] As a safety measure, NASA designated Space Shuttle Discovery as the dedicated rescue vehicle for STS-115, prepared for launch as STS-301 if Atlantis encountered irreparable damage rendering re-entry unsafe. This contingency plan allowed Atlantis's crew to seek safe haven on the International Space Station for up to 80 days while awaiting rescue, but the mission's success rendered the plan unnecessary, and it was subsequently canceled.[43]Mission Highlights

Wake-Up Calls