Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mobile phone

View on Wikipedia

A mobile phone or cell phone is a portable wireless telephone that allows users to make and receive calls over a radio frequency link while moving within a designated telephone service area, unlike fixed-location phones (landline phones). This radio frequency link connects to the switching systems of a mobile phone operator, providing access to the public switched telephone network (PSTN). Modern mobile telephony relies on a cellular network architecture, which is why mobile phones are often referred to as 'cell phones' in North America.

Beyond traditional voice communication, digital mobile phones have evolved to support a wide range of additional services. These include text messaging, multimedia messaging, email, and internet access (via LTE, 5G NR or Wi-Fi), as well as short-range wireless technologies like Bluetooth, infrared, and ultra-wideband (UWB).

Mobile phones also support a variety of multimedia capabilities, such as digital photography, video recording, and gaming. In addition, they enable multimedia playback and streaming, including video content, as well as radio and television streaming. Furthermore, mobile phones offer satellite-based services, such as navigation and messaging, as well as business applications and payment solutions (via scanning QR codes or near-field communication (NFC)). Mobile phones offering only basic features are often referred to as feature phones (slang: dumbphones), while those with advanced computing power are known as smartphones.[1]

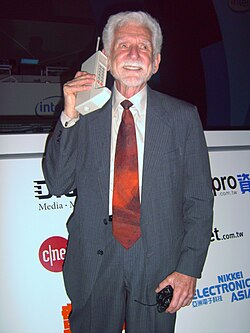

The first handheld mobile phone was demonstrated by Martin Cooper of Motorola in New York City on 3 April 1973, using a handset weighing c. 2 kilograms (4.4 lbs).[2] In 1979, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) launched the world's first cellular network in Japan.[3] In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first commercially available handheld mobile phone. From 1993 to 2024, worldwide mobile phone subscriptions grew to over 9.1 billion; enough to provide one for every person on Earth.[4][5] In 2024, the top smartphone manufacturers worldwide were Samsung, Apple and Xiaomi; smartphone sales represented about 50 percent of total mobile phone sales.[6][7] For feature phones as of 2016[update], the top-selling brands were Samsung, Nokia and Alcatel.[8]

Mobile phones are considered an important human invention as they have been one of the most widely used and sold pieces of consumer technology.[9] The growth in popularity has been rapid in some places; for example, in the UK, the total number of mobile phones overtook the number of houses in 1999.[10] Today, mobile phones are globally ubiquitous,[11] and in almost half the world's countries, over 90% of the population owns at least one.[12]

Name

[edit]"Mobile phone" is the most common English language term, while the term "cell phone" is in more common use in North America[13] – both are in essence shorter versions of "mobile telephone" and "cellular telephone", respectively. Often in colloquial terms it is referred to as simply phone, mobile or cell. A number of alternative words have also been used to describe a mobile phone, most of which have fallen out of use, including: "mobile handset", "wireless phone", "mobile terminal", "cellular device", "hand phone", and "pocket phone".

History

[edit]

A handheld mobile radio telephone service was envisioned in the early stages of radio engineering. In 1917, Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt filed a patent for a "pocket-size folding telephone with a very thin carbon microphone". Early predecessors of cellular phones included analog radio communications from ships and trains. The race to create truly portable telephone devices began after World War II, with developments taking place in many countries. The advances in mobile telephony have been traced in successive "generations", starting with the early zeroth-generation (0G) services, such as Bell System's Mobile Telephone Service and its successor, the Improved Mobile Telephone Service. These 0G systems were not cellular, supported a few simultaneous calls, and were very expensive.

Mobile phone technology has progressed significantly since its origins, evolving from large car-mounted systems to compact, handheld devices.[14][15] Early mobile phones required vehicle installation due to their size and power needs.[16][17] A major breakthrough came in 1973, when the first handheld cellular mobile phone was demonstrated by John F. Mitchell[18][19] and Martin Cooper of Motorola, using a handset weighing 2 kilograms (4.4 lb).[2][20][21] Cooper made the first ever call on a cell phone when he called Joel S. Engel, a rival of his who worked for AT&T, saying, "I'm calling you on a cell phone, but a real cell phone, a personal, handheld, portable cell phone."[22]

The first commercial automated cellular network (1G) analog was launched in Japan by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone in 1979. This was followed in 1981 by the simultaneous launch of the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.[23] Several other countries then followed in the early to mid-1980s. These first-generation (1G) systems could support far more simultaneous calls but still used analog cellular technology. In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first commercially available handheld mobile phone.

In 1991, the second-generation (2G) digital cellular technology was launched in Finland by Radiolinja on the GSM standard. This sparked competition in the sector as the new operators challenged the incumbent 1G network operators. The GSM standard is a European initiative expressed at the CEPT ("Conférence Européenne des Postes et Telecommunications", European Postal and Telecommunications conference). The Franco-German R&D cooperation demonstrated the technical feasibility, and in 1987, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between 13 European countries that agreed to launch a commercial service by 1991. The first version of the GSM standard had 6,000 pages. The IEEE and RSE awarded Thomas Haug and Philippe Dupuis the 2018 James Clerk Maxwell medal for their contributions to the first digital mobile telephone standard.[24] In 2018, the GSM was used by over 5 billion people in over 220 countries. The GSM (2G) has evolved into 3G, 4G and 5G. The standardization body for GSM started at the CEPT Working Group GSM (Group Special Mobile) in 1982 under the umbrella of CEPT. In 1988, ETSI was established, and all CEPT standardization activities were transferred to ETSI. Working Group GSM became Technical Committee GSM. In 1991, it became Technical Committee SMG (Special Mobile Group) when ETSI tasked the committee with UMTS (3G). In addition to transmitting voice over digital signals, the 2G network introduced data services for mobile, starting with SMS text messages, then expanding to Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS), and mobile internet with a theoretical maximum transfer speed of 384 kbit/s (48 kB/s).

In 2001, the third-generation (3G) was launched in Japan by NTT DoCoMo on the WCDMA standard.[25] This was followed by 3.5G or 3G+ enhancements based on the high-speed packet access (HSPA) family, allowing UMTS networks to have higher data transfer speeds and capacity. 3G is able to provide mobile broadband access of several Mbit/s to smartphones and mobile modems in laptop computers. This ensures it can be applied to mobile Internet access, VoIP, video calls, and sending large e-mail messages, as well as watching videos, typically in standard-definition quality.

By 2009, it had become clear that, at some point, 3G networks would be overwhelmed by the growth of bandwidth-intensive applications, such as streaming media.[26] Consequently, the industry began looking to data-optimized fourth-generation (4G) technologies, with the promise of speed improvements up to tenfold over existing 3G technologies. The first publicly available LTE service was launched in Scandinavia by TeliaSonera in 2009. In the 2010s, 4G technology has found diverse applications across various sectors, showcasing its versatility in delivering high-speed wireless communication, such as mobile broadband, the internet of things (IoT), fixed wireless access, and multimedia streaming (including music, video, radio, and television).

Deployment of fifth-generation (5G) cellular networks commenced worldwide in 2019. The term "5G" was originally used in research papers and projects to denote the next major phase in mobile telecommunication standards beyond the 4G/IMT-Advanced standards. The 3GPP defines 5G as any system that adheres to the 5G NR (5G New Radio) standard. 5G can be implemented in low-band, mid-band or high-band millimeter-wave, with download speeds that can achieve gigabit-per-second (Gbit/s) range, aiming for a network latency of 1 ms. This near-real-time responsiveness and improved overall data performance are crucial for applications like online gaming, augmented and virtual reality, autonomous vehicles, IoT, and critical communication services.

Types

[edit]

Smartphone

[edit]Smartphones are defined by their advanced computing capabilities, which include internet connectivity and access to a wide range of applications. The International Telecommunication Union measures those with Internet connection, which it calls Active Mobile-Broadband subscriptions (which includes tablets, etc.). In developed countries, smartphones have largely replaced earlier mobile technologies, while in developing regions, they account for around 50% of all mobile phone usage.

Feature phone

[edit]Feature phone is a term typically used as a retronym to describe mobile phones which are limited in capabilities in contrast to a modern smartphone. Feature phones typically provide voice calling and text messaging functionality, in addition to basic multimedia and Internet capabilities, and other services offered by the user's wireless service provider. A feature phone has additional functions over and above a basic mobile phone, which is only capable of voice calling and text messaging.[28][29] Feature phones and basic mobile phones tend to use a proprietary, custom-designed software and user interface. By contrast, smartphones generally use a mobile operating system that often shares common traits across devices.

Infrastructure

[edit]

The critical advantage that modern cellular networks have over predecessor systems is the concept of frequency reuse allowing many simultaneous telephone conversations in a given service area. This allows efficient use of the limited radio spectrum allocated to mobile services, and lets thousands of subscribers converse at the same time within a given geographic area.

Former systems would cover a service area with one or two powerful base stations with a range of up to tens of kilometers' (miles), using only a few sets of radio channels (frequencies). Once these few channels were in use by customers, no further customers could be served until another user vacated a channel. It would be impractical to give every customer a unique channel since there would not be enough bandwidth allocated to the mobile service. As well, technical limitations such as antenna efficiency and receiver design limit the range of frequencies a customer unit could use.

A cellular network mobile phone system gets its name from dividing the service area into many small cells, each with a base station with (for example) a useful range on the order of a kilometer (mile). These systems have dozens or hundreds of possible channels allocated to them. When a subscriber is using a given channel for a telephone connection, that frequency is unavailable for other customers in the local cell and in the adjacent cells. However, cells further away can re-use that channel without interference as the subscriber's handset is too far away to be detected. The transmitter power of each base station is coordinated to efficiently service its own cell, but not to interfere with the cells further away.

Automation embedded in the customer's handset and in the base stations control all phases of the call, from detecting the presence of a handset in a service area, temporary assignment of a channel to a handset making a call, interface with the land-line side of the network to connect to other subscribers, and collection of billing information for the service. The automation systems can control the "hand off" of a customer handset moving between one cell and another so that a call in progress continues without interruption, changing channels if required. In the earliest mobile phone systems by contrast, all control was done manually; the customer would search for an unoccupied channel and speak to a mobile operator to request connection of a call to a landline number or another mobile. At the termination of the call the mobile operator would manually record the billing information.

Mobile phones communicate with cell towers that are placed to give coverage across a telephone service area, which is divided up into 'cells'. Each cell uses a different set of frequencies from neighboring cells, and will typically be covered by three towers placed at different locations. The cell towers are usually interconnected to each other and the phone network and the internet by wired connections. Due to bandwidth limitations each cell will have a maximum number of cell phones it can handle at once. The cells are therefore sized depending on the expected usage density, and may be much smaller in cities. In that case much lower transmitter powers are used to avoid broadcasting beyond the cell.

In order to handle the high traffic, multiple towers can be set up in the same area (using different frequencies). This can be done permanently or temporarily such as at special events or in disasters. Cell phone companies will bring a truck with equipment to host the abnormally high traffic.

Capacity was further increased when phone companies implemented digital networks. With digital, one frequency can host multiple simultaneous calls.

Additionally, short-range Wi-Fi infrastructure is often used by smartphones as much as possible as it offloads traffic from cell networks on to local area networks.

Hardware

[edit]The common components found on all mobile phones are:

- A central processing unit (CPU), the processor of phones. The CPU is a microprocessor fabricated on a metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) chip.

- A battery, providing the power source for the phone functions. A modern handset typically uses a lithium-ion battery (LIB), whereas older handsets used nickel–metal hydride (Ni–MH) batteries.

- An input mechanism to allow the user to interact with the phone. These are a keypad for feature phones, and touch screens for most smartphones (typically with capacitive sensing).

- A display which echoes the user's typing, and displays text messages, contacts, and more. The display is typically either a liquid-crystal display (LCD) or organic light-emitting diode (OLED) display.

- Speakers for sound.

- Subscriber identity module (SIM) cards and removable user identity module (R-UIM) cards.

- A hardware notification LED on some phones

Low-end mobile phones are often referred to as feature phones and offer basic telephony. Handsets with more advanced computing ability through the use of native software applications are known as smartphones. The first GSM phones and many feature phones had NOR flash memory, from which processor instructions could be executed directly in an execute in place architecture and allowed for short boot times. With smartphones, NAND flash memory was adopted as it has larger storage capacities and lower costs, but causes longer boot times because instructions cannot be executed from it directly, and must be copied to RAM memory first before execution.[30]

Central processing unit

[edit]Mobile phones have central processing units (CPUs), similar to those in computers, but optimised to operate in low power environments.

Mobile CPU performance depends not only on the clock rate (generally given in multiples of hertz)[31] but also the memory hierarchy also greatly affects overall performance. Because of these problems, the performance of mobile phone CPUs is often more appropriately given by scores derived from various standardized tests to measure the real effective performance in commonly used applications.

Display

[edit]One of the main characteristics of phones is the screen. Depending on the device's type and design, the screen fills most or nearly all of the space on a device's front surface. Many smartphone displays have an aspect ratio of 16:9, but taller aspect ratios became more common in 2017.

Screen sizes are often measured in diagonal inches or millimeters; feature phones generally have screen sizes below 90 millimetres (3.5 in). Phones with screens larger than 130 millimetres (5.2 in) are often called "phablets." Smartphones with screens over 115 millimetres (4.5 in) in size are commonly difficult to use with only a single hand, since most thumbs cannot reach the entire screen surface; they may need to be shifted around in the hand, held in one hand and manipulated by the other, or used in place with both hands. Due to design advances, some modern smartphones with large screen sizes and "edge-to-edge" designs have compact builds that improve their ergonomics, while the shift to taller aspect ratios have resulted in phones that have larger screen sizes whilst maintaining the ergonomics associated with smaller 16:9 displays.[32][33][34]

Liquid-crystal displays are the most common; others are IPS, LED, OLED, and AMOLED displays. Some displays are integrated with pressure-sensitive digitizers, such as those developed by Wacom and Samsung,[35] and Apple's "3D Touch" system.

Sound

[edit]In sound, smartphones and feature phones vary little. Some audio-quality enhancing features, such as Voice over LTE and HD Voice, have appeared and are often available on newer smartphones. Sound quality can remain a problem due to the design of the phone, the quality of the cellular network and compression algorithms used in long-distance calls.[36][37] Audio quality can be improved using a VoIP application over WiFi.[38] Cellphones have small speakers so that the user can use a speakerphone feature and talk to a person on the phone without holding it to their ear. The small speakers can also be used to listen to digital audio files of music or speech or watch videos with an audio component, without holding the phone close to the ear.

Battery

[edit]The typical lifespan of a mobile phone battery is approximately two to three years, although this varies based on usage patterns, environmental conditions, and overall care. Most modern mobile phones use lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries, which are designed to endure between 500 and 2,500 charge cycles. The exact number of cycles depends on factors such as charging habits, operating temperature, and battery management systems.[39]

Li-ion batteries gradually degrade over time due to chemical aging, leading to reduced capacity and performance, often noticeable after one or two years of regular use. Unlike older battery types, such as nickel-metal hydride (Ni-MH), Li-ion batteries do not need to be fully discharged to maintain their longevity. In fact, they perform best when kept between 30% and 80% of their full charge.[40] While practices such as avoiding excessive heat and minimizing overcharging can help preserve battery health, many modern devices include built-in safeguards.[41] These safeguards, typically managed by the phone's internal battery management system (BMS), prevent overcharging by cutting off power once the battery reaches full capacity. Additionally, most contemporary chargers and devices are designed to regulate charging to minimize stress on the battery. Therefore, while good charging habits can positively impact battery longevity, most users benefit from these integrated protections, making battery maintenance less of a concern in day-to-day use.[42][43]

Future mobile phone batteries are expected to utilize advanced technologies such as silicon-carbon (Si/C) batteries and solid-state batteries, which promise to offer higher energy densities, longer lifespans, and improved safety compared to current lithium-ion batteries.[44][45][46]

SIM card

[edit]

Mobile phones require a small microchip called a Subscriber Identity Module or SIM card, in order to function. The SIM card is approximately the size of a small postage stamp and is usually placed underneath the battery in the rear of the unit. The SIM securely stores the service-subscriber key (IMSI) and the Ki used to identify and authenticate the user of the mobile phone. The SIM card allows users to change phones by simply removing the SIM card from one mobile phone and inserting it into another mobile phone or broadband telephony device, provided that this is not prevented by a SIM lock. The first SIM card was made in 1991 by Munich smart card maker Giesecke & Devrient for the Finnish wireless network operator Radiolinja.[citation needed]

A hybrid mobile phone can hold up to four SIM cards, with a phone having a different device identifier for each SIM Card. SIM and R-UIM cards may be mixed together to allow both GSM and CDMA networks to be accessed. From 2010 onwards, such phones became popular in emerging markets,[47] and this was attributed to the desire to obtain the lowest calling costs.

When the removal of a SIM card is detected by the operating system, it may deny further operation until a reboot.[48]

Software

[edit]Software platforms

[edit]

Feature phones have basic software platforms. Smartphones have advanced software platforms. Android OS has been the best-selling OS worldwide on smartphones since 2011.[49] As of March 2025, Android OS had 71.9% of the overall market share, while the second-largest, iOS, had 27.7%.[50]

Mobile app

[edit]A mobile app is a computer program designed to run on a mobile device, such as a smartphone. The term "app" is a shortening of the term "software application".

- Messaging

A common data application on mobile phones is Short Message Service (SMS) text messaging. The first SMS message was sent from a computer to a mobile phone in 1992 in the UK while the first person-to-person SMS from phone to phone was sent in Finland in 1993. The first mobile news service, delivered via SMS, was launched in Finland in 2000,[51] and subsequently many organizations provided "on-demand" and "instant" news services by SMS. Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) was introduced in March 2002.[52]

Application stores

[edit]The introduction of Apple's App Store for the iPhone and iPod Touch in July 2008 popularized manufacturer-hosted online distribution for third-party applications (software and computer programs) focused on a single platform. There are a huge variety of apps, including video games, music products and business tools. Up until that point, smartphone application distribution depended on third-party sources providing applications for multiple platforms, such as GetJar, Handango, Handmark, and PocketGear. Following the success of the App Store, other smartphone manufacturers launched application stores, such as Google's Android Market (later renamed to the Google Play Store), RIM's BlackBerry App World, or Android-related app stores like Aptoide, Cafe Bazaar, F-Droid, GetJar, and Opera Mobile Store. In February 2014, 93% of mobile developers were targeting smartphones first for mobile app development.[53]

Sales

[edit]By manufacturer

[edit]| Rank | Manufacturer | Strategy Analytics report[54] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samsung | 21% | ||

| 2 | Apple | 16% | ||

| 3 | Xiaomi | 13% | ||

| 4 | Oppo | 10% | ||

| 5 | Vivo | 9% | ||

| Others | 31% | |||

| Note: Vendor shipments are branded shipments and exclude OEM sales for all vendors. | ||||

As of 2022, the top five manufacturers worldwide were Samsung (21%), Apple (16%), Xiaomi (13%), Oppo (10%), and Vivo (9%).[54]

- History

From 1983 to 1998, Motorola was market leader in mobile phones. Nokia was the market leader in mobile phones from 1998 to 2012.[55] In Q1 2012, Samsung surpassed Nokia, selling 93.5 million units as against Nokia's 82.7 million units. Samsung has retained its top position since then.

Aside from Motorola, European brands such as Nokia, Siemens and Ericsson once held large sway over the global mobile phone market, and many new technologies were pioneered in Europe. By 2010, the influence of European companies had significantly decreased due to fierce competition from American and Asian companies, to where most technical innovation had shifted.[56][57] Apple and Google, both of the United States, also came to dominate mobile phone software.[56]

By mobile phone operator

[edit]The world's largest individual mobile operator by number of subscribers is China Mobile, which has over 902 million mobile phone subscribers as of June 2018[update].[58] Over 50 mobile operators have over ten million subscribers each, and over 150 mobile operators had at least one million subscribers by the end of 2009.[59] In 2014, there were more than seven billion mobile phone subscribers worldwide, a number that is expected to keep growing.[citation needed][needs update]

Use

[edit]

Mobile phones are used for a variety of purposes, such as keeping in touch with family members, for conducting business, and in order to have access to a telephone in the event of an emergency. Some people carry more than one mobile phone for different purposes, such as for business and personal use. Multiple SIM cards may be used to take advantage of the benefits of different calling plans. For example, a particular plan might provide for cheaper local calls, long-distance calls, international calls, or roaming.

The mobile phone has been used in a variety of diverse contexts in society. For example:

- A study by Motorola found that one in ten mobile phone subscribers have a second phone that is often kept secret from other family members. These phones may be used to engage in such activities as extramarital affairs or clandestine business dealings.[60]

- Some organizations assist victims of domestic violence by providing mobile phones for use in emergencies. These are often refurbished phones.[61]

- The advent of widespread text-messaging has resulted in the cell phone novel, the first literary genre to emerge from the cellular age, via text messaging to a website that collects the novels as a whole.[62]

- Mobile telephony also facilitates activism and citizen journalism.

- The United Nations reported that mobile phones have spread faster than any other form of technology and can improve the livelihood of the poorest people in developing countries, by providing access to information in places where landlines or the Internet are not available, especially in the least developed countries. Use of mobile phones also spawns a wealth of micro-enterprises, by providing such work as selling airtime on the streets and repairing or refurbishing handsets.[63]

- In Mali and other African countries, people used to travel from village to village to let friends and relatives know about weddings, births, and other events. This can now be avoided in areas with mobile phone coverage, which are usually more extensive than areas with just land-line penetration.

- The TV industry has recently started using mobile phones to drive live TV viewing through mobile apps, advertising, social TV, and mobile TV.[64] It is estimated that 86% of Americans use their mobile phone while watching TV.

- In some parts of the world, mobile phone sharing is common. Cell phone sharing is prevalent in urban India, as families and groups of friends often share one or more mobile phones among their members. There are obvious economic benefits, but often familial customs and traditional gender roles play a part.[65] It is common for a village to have access to only one mobile phone, perhaps owned by a teacher or missionary, which is available to all members of the village for necessary calls.[66]

- Smartphones also have the use for individuals who suffer from diabetes. There are apps for patients with diabetes to self monitor their blood sugar, and can sync with flash monitors. The apps have a feature to send automated feedback or possible warnings to other family members or healthcare providers in the case of an emergency.

Content distribution

[edit]In 1998, one of the first examples of distributing and selling media content through the mobile phone was the sale of ringtones by Radiolinja in Finland. Soon afterwards, other media content appeared, such as news, video games, jokes, horoscopes, TV content and advertising. Most early content for mobile phones tended to be copies of legacy media, such as banner advertisements or TV news highlight video clips. Recently, unique content for mobile phones has been emerging, from ringtones and ringback tones to mobisodes, video content that has been produced exclusively for mobile phones.[citation needed]

Mobile banking and payment

[edit]

In many countries, mobile phones are used to provide mobile banking services, which may include the ability to transfer cash payments by secure SMS text message. Kenya's M-PESA mobile banking service, for example, allows customers of the mobile phone operator Safaricom to hold cash balances which are recorded on their SIM cards. Cash can be deposited or withdrawn from M-PESA accounts at Safaricom retail outlets located throughout the country and can be transferred electronically from person to person and used to pay bills to companies.

Branchless banking has also been successful in South Africa and the Philippines. A pilot project in Bali was launched in 2011 by the International Finance Corporation and an Indonesian bank, Bank Mandiri.[67]

Mobile payments were first trialled in Finland in 1998 when two Coca-Cola vending machines in Espoo were enabled to work with SMS payments. Eventually, the idea spread and in 1999, the Philippines launched the country's first commercial mobile payments systems with mobile operators Globe and Smart.[citation needed]

Some mobile phones can make mobile payments via direct mobile billing schemes, or through contactless payments if the phone and the point of sale support near field communication (NFC).[68] Enabling contactless payments through NFC-equipped mobile phones requires the co-operation of manufacturers, network operators, and retail merchants.[69][70]

Mobile tracking

[edit]Mobile phones are commonly used to collect location data. While the phone is turned on, the geographical location of a mobile phone can be determined easily (whether it is being used or not) using a technique known as multilateration to calculate the differences in time for a signal to travel from the mobile phone to each of several cell towers near the owner of the phone.[71][72]

The movements of a mobile phone user can be tracked by their service provider and, if desired, by law enforcement agencies and their governments. Both the SIM card and the handset can be tracked.[71]

China has proposed using this technology to track the commuting patterns of Beijing city residents.[73] In the UK and US, law enforcement and intelligence services use mobile phones to perform surveillance operations.[74]

Hackers have been able to track a phone's location, read messages, and record calls, through obtaining a subscriber's phone number.[75]

Electronic waste regulation

[edit]

Studies have shown that around 40–50% of the environmental impact of mobile phones occurs during the manufacture of their printed wiring boards and integrated circuits.[76]

The average user replaces their mobile phone every 11 to 18 months,[77] and the discarded phones then contribute to electronic waste. Mobile phone manufacturers within Europe are subject to the WEEE directive, and Australia has introduced a mobile phone recycling scheme.[78]

Apple Inc. had an advanced robotic disassembler and sorter called Liam specifically for recycling outdated or broken iPhones.[79]

Theft

[edit]According to the Federal Communications Commission, one out of three robberies involve the theft of a cellular phone.[citation needed] Police data in San Francisco show that half of all robberies in 2012 were thefts of cellular phones.[citation needed] An online petition on Change.org, called Secure our Smartphones, urged smartphone manufacturers to install kill switches in their devices to make them unusable if stolen. The petition is part of a joint effort by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón and was directed to the CEOs of the major smartphone manufacturers and telecommunication carriers.[80] On 10 June 2013, Apple announced that it would install a "kill switch" on its next iPhone operating system, due to debut in October 2013.[81]

All mobile phones have a unique identifier called IMEI. Anyone can report their phone as lost or stolen with their Telecom Carrier, and the IMEI would be blacklisted with a central registry.[82] Telecom carriers, depending upon local regulation can or must implement blocking of blacklisted phones in their network. There are, however, a number of ways to circumvent a blacklist. One method is to send the phone to a country where the telecom carriers are not required to implement the blacklisting and sell it there,[83] another involves altering the phone's IMEI number.[84] Even so, mobile phones typically have less value on the second-hand market if the phones original IMEI is blacklisted.

Conflict minerals

[edit]Demand for metals used in mobile phones and other electronics fuelled the Second Congo War, which claimed almost 5.5 million lives.[85] In a 2012 news story, The Guardian reported: "In unsafe mines deep underground in eastern Congo, children are working to extract minerals essential for the electronics industry. The profits from the minerals finance the bloodiest conflict since the second world war; the war has lasted nearly 20 years and has recently flared up again. For the last 15 years, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been a major source of natural resources for the mobile phone industry."[86] The company Fairphone has worked to develop a mobile phone that does not contain conflict minerals.[citation needed]

Kosher phones

[edit]Due to concerns by the Orthodox Jewish rabbinate in Britain that texting by youths could waste time and lead to "immodest" communication, the rabbinate recommended that phones with text-messaging capability not be used by children; to address this, they gave their official approval to a brand of "Kosher" phones with no texting capabilities. Although these phones are intended to prevent immodesty, some vendors report good sales to adults who prefer the simplicity of the devices; other Orthodox Jews question the need for them.[87]

In Israel, similar phones to kosher phones with restricted features exist to observe the sabbath; under Orthodox Judaism, the use of any electrical device is generally prohibited during this time, other than to save lives, or reduce the risk of death or similar needs. Such phones are approved for use by essential workers, such as health, security, and public service workers.[88]

Restrictions

[edit]Restrictions on the use of mobile phones are applied in a number of different contexts, often with the goal of health, safety, security or proper functioning of an establishment, or as a matter of etiquette. Such contexts include:

While driving

[edit]

Mobile phone use while driving, including talking on the phone, texting, or operating other phone features, is common but controversial. It is widely considered dangerous due to distracted driving. Being distracted while operating a motor vehicle has been shown to increase the risk of accidents. In September 2010, the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reported that 995 people were killed by drivers distracted by cell phones. In March 2011, a US insurance company, State Farm Insurance, announced the results of a study which showed 19% of drivers surveyed accessed the Internet on a smartphone while driving.[89] Many jurisdictions prohibit the use of mobile phones while driving. In Egypt, Israel, Japan, Portugal, and Singapore, both handheld and hands-free use of a mobile phone (which uses a speakerphone) is banned. In other countries, including the UK and France and in many US states, only handheld phone use is banned while hands-free use is permitted.

A 2011 study reported that over 90% of college students surveyed text (initiate, reply or read) while driving.[90] The scientific literature on the dangers of driving while sending a text message from a mobile phone, or texting while driving, is limited. A simulation study at the University of Utah found a sixfold increase in distraction-related accidents when texting.[91]

Due to the increasing complexity of mobile phones, they are often more like mobile computers in their available uses. This has introduced additional difficulties for law enforcement officials when attempting to distinguish one usage from another in drivers using their devices. This is more apparent in countries which ban both handheld and hands-free usage, rather than those which ban handheld use only, as officials cannot easily tell which function of the mobile phone is being used simply by looking at the driver. This can lead to drivers being stopped for using their device illegally for a phone call when, in fact, they were using the device legally, for example, when using the phone's incorporated controls for car stereo, GPS or satnav.

A 2010 study reviewed the incidence of mobile phone use while cycling and its effects on behaviour and safety.[92] In 2013, a national survey in the US reported the number of drivers who reported using their cellphones to access the Internet while driving had risen to nearly one of four.[93] A study conducted by the University of Vienna examined approaches for reducing inappropriate and problematic use of mobile phones, such as using mobile phones while driving.[94]

Accidents involving a driver being distracted by talking on a mobile phone have begun to be prosecuted as negligence similar to speeding. In the United Kingdom, from 27 February 2007, motorists who are caught using a hand-held mobile phone while driving will have three penalty points added to their license in addition to the fine of £60.[95] This increase was introduced to try to stem the increase in drivers ignoring the law.[96] Japan prohibits all mobile phone use while driving, including use of hands-free devices. New Zealand has banned hand-held cell phone use since 1 November 2009. Many states in the United States have banned texting on cell phones while driving. Illinois became the 17th American state to enforce this law.[97] As of July 2010[update], 30 states had banned texting while driving, with Kentucky becoming the most recent addition on 15 July.[98]

Public Health Law Research maintains a list of distracted driving laws in the United States. This database of laws provides a comprehensive view of the provisions of laws that restrict the use of mobile communication devices while driving for all 50 states and the District of Columbia between 1992 when first law was passed, through 1 December 2010. The dataset contains information on 22 dichotomous, continuous or categorical variables including, for example, activities regulated (e.g., texting versus talking, hands-free versus handheld), targeted populations, and exemptions.[99]

On aircraft

[edit]In the U.S., the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations prohibit the use of mobile phones aboard aircraft in flight.[100] Contrary to popular misconception, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) does not actually prohibit the use of personal electronic devices (including cell phones) on aircraft. Paragraph (b)(5) of 14 CFR 91.21 permits airlines to determine if devices can be used in flight, allowing use of "any other portable electronic device that the operator of the aircraft has determined will not cause interference with the navigation or communication system of the aircraft on which it is to be used."[101]

In Europe, regulations and technology have allowed the limited introduction of the use of passenger mobile phones on some commercial flights, and elsewhere in the world many airlines are moving towards allowing mobile phone use in flight.[102] Many airlines still do not allow the use of mobile phones on aircraft.[103] Those that do often ban the use of mobile phones during take-off and landing.

Many passengers are pressing airlines and their governments to allow and deregulate mobile phone use, while some airlines, under the pressure of competition, are also pushing for deregulation or seeking new technology which could solve the present problems.[104] Official aviation agencies and safety boards are resisting any relaxation of the present safety rules unless and until it can be conclusively shown that it would be safe to do so. There are both technical and social factors which make the issues more complex than a simple discussion of safety versus hazard.[105]While walking

[edit]

Between 2011 and 2019, an estimated 30,000 walking injuries occurred in the US related to using a cellphone, leading to some jurisdictions attempting to ban pedestrians from using their cellphones.[106][107][108] Other countries, such as China and the Netherlands, have introduced special lanes for smartphone users to help direct and manage them.[109][110]

In prisons

[edit]In hospitals

[edit]As of 2007, some hospitals had banned mobile devices due to a common misconception that their use would create significant electromagnetic interference.[113][114]

Health effects

[edit]Screen time, the amount of time using a device with a screen, has become an issue for mobile phones since the adaptation of smartphones.[115] Research is being conducted to show the correlation between screen time and the mental and physical harm in child development.[116] To prevent harm, some parents and even governments have placed restrictions on its usage.[117][118]

There have been rumors that mobile phone use can cause cancer, but this is a myth.[119][120]

While there are rumors of mobile phones causing cancer, there was a study conducted by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) that stated the there could be an increase risk of brain tumors with the use of smartphones, this is not confirmed. They also stated that with the lack of data for the research and the usage periods of 15 years will warrant further research for smartphones and the cause of brain tumors.[121]

Educational impact

[edit]A study by the London School of Economics found that banning mobile phones in schools could increase pupils' academic performance, providing benefits equal to one extra week of schooling per year.[122]

Culture and popularity

[edit]Mobile phones are considered an important human invention as it has been one of the most widely used and sold pieces of consumer technology.[9][11] They have also become culturally symbolic. In Japanese mobile phone culture for example, mobile phones are often decorated with charms. They have also become fashion symbols at times.[123] The Motorola Razr V3 and LG Chocolate are two examples of devices that were popular for being fashionable while not necessarily focusing on the original purpose of mobile phones, i.e. a device to provide mobile telephony.[124]

Some have also suggested that mobile phones or smartphones are a status symbol.[125] For example a research paper suggested that owning specifically an Apple iPhone was seen to be a status symbol.[126]

Text messaging, which are performed on mobile phones, has also led to the creation of 'SMS language'. It also led to the growing popularity of emojis.[127]

See also

[edit]- Camera phone

- Cellular frequencies

- Customer proprietary network information

- Field telephone

- List of countries by number of mobile phones in use

- Mobile broadband

- Mobile Internet device (MID)

- Mobile phone accessories

- Mobile Phone Museum

- Mobile phones on aircraft

- Mobile phone use in schools

- Mobile technology

- Mobile telephony

- Mobile phone form factor

- Optical head-mounted display

- OpenBTS

- Pager

- Personal digital assistant

- Personal Handy-phone System

- Prepaid mobile phone

- Two-way radio

- Push-button telephone

- Radiotelephone

- Rechargeable battery

- Smombie

- Surveillance

- Tethering

- VoIP phone

References

[edit]- ^ Srivastava, Viranjay M.; Singh, Ghanshyam (2013). MOSFET Technologies for Double-Pole Four-Throw Radio-Frequency Switch. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-319-01165-3.

- ^ a b Teixeira, Tania (23 April 2010). "Meet the man who invented the mobile phone". BBC News. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Timeline from 1G to 5G: A Brief History on Cell Phones". CENGN. 21 September 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Petroc. "Mobile Phone Subscriptions Worldwide 2024." Statista, 10 Mar. 2025.

- ^ "Mobile penetration". 9 July 2010.

Almost 40 percent of the world's population, 2.7 billion people, are online. The developing world is home to about 826 million female internet users and 980 million male internet users. The developed world is home to about 475 million female Internet users and 483 million male Internet users.

- ^ Sherif, Ahmed. "Smartphone Market Shares by Vendor 2009–2024." Statista, 14 Jan. 2025.

- ^ "Gartner Says Worldwide Smartphone Sales Grew 3.9 Percent in First Quarter of 2016". Gartner. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ "Nokia Captured 9% Feature Phone Marketshare Worldwide in 2016". Strategyanalytics.com. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ a b Harris, Arlene; Cooper, Martin (2019). "Mobile phones: Impacts, challenges, and predictions". Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 1: 15–17. doi:10.1002/hbe2.112. ISSN 2578-1863. S2CID 187189041.

- ^ "BBC News | Business | Mobile phone sales surge".

- ^ a b Gupta, Gireesh K. (2011). "Ubiquitous mobile phones are becoming indispensable". ACM Inroads. 2 (2): 32–33. doi:10.1145/1963533.1963545. S2CID 2942617.

- ^ "Mobile phones are becoming ubiquitous". International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 17 February 2022. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "cell phone, n. meanings, etymology and more | Oxford English Dictionary".

- ^ US3663762A, Jr, Edward Joel Amos, "Mobile communication system", issued 16 May 1972

- ^ Meurling, J., Jeans, R. The Mobile Phone Book Communications Week International, 1994, ISBN 0-9524031-0-2 page 16

- ^ Goggin, Gerard (2006). Cell phone culture: mobile technology in everyday life. London ; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-36743-1. OCLC 64595837.

- ^ Garrard, Garry A. (1998). Cellular communications: worldwide market development. The Artech House mobile communications series. Boston: Artech House. ISBN 978-0-89006-923-3.

- ^ "John F. Mitchell Biography". Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ "Who invented the cell phone?". Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ "A chat with the man behind mobiles". 21 April 2003. Retrieved 27 June 2025.

- ^ US3906166A, Cooper, Martin; Dronsuth, Richard W. & Leitich, Albert J. et al., "Radio telephone system", issued 16 September 1975

- ^ Korn, Jennifer (3 April 2023). "50 years ago, he made the first cell phone call". CNN. Retrieved 30 June 2025.

- ^ "Swedish National Museum of Science and Technology". Tekniskamuseet.se. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ "Duke of Cambridge Presents Maxwell Medals to GSM Developers". IEEE United Kingdom and Ireland Section. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "History of UMTS and 3G Development". Umtsworld.com. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ Fahd Ahmad Saeed. "Capacity Limit Problem in 3G Networks". Purdue School of Engineering. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Statistics". ITU.

- ^ "feature phone Definition from PC Magazine Encyclopedia". www.pcmag.com.

- ^ Todd Hixon, Two Weeks With A Dumb Phone Archived 30 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, 13 November 2012

- ^ Micheloni, Rino; Crippa, Luca; Marelli, Alessia (27 July 2010). Inside NAND Flash Memories. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-9431-5.

- ^ "CPU Frequency". CPU World Glossary. CPU World. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ "Don't call it a phablet: the 5.5" Samsung Galaxy S7 Edge is narrower than many 5.2" devices". PhoneArena. 21 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ "We're gonna need Pythagoras' help to compare screen sizes in 2017". The Verge. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ "The Samsung Galaxy S8 will change the way we think about display sizes". The Verge. Vox Media. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Ward, J. R.; Phillips, M. J. (1 April 1987). "Digitizer Technology: Performance Characteristics and the Effects on the User Interface". IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications. 7 (4): 31–44. doi:10.1109/MCG.1987.276869. ISSN 0272-1716. S2CID 16707568.

- ^ Jeff Hecht (30 September 2014). "Why Mobile Voice Quality Still Stinks – and How to Fix It". IEEE.

- ^ Elena Malykhina. "Why Is Cell Phone Call Quality So Terrible?". Scientific American.

- ^ Alan Henry (22 May 2014). "What's the Best Mobile VoIP App?". Lifehacker. Gawker Media.

- ^ Taylor, Martin. "How To Prolong Your Cell Phone Battery's Life Span". Phonedog.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Should lithium ion batteries be fully discharged before charging?-battery-knowledge | Large Power". www.large.net. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ "What is a Lithium-ion Battery Protection IC? – Understanding the Role, Functionality, and Importance". ABLIC Inc. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ "Iphone Battery and Performance". Apple Support. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Hill, Simon. "Should You Leave Your Smartphone Plugged Into The Charger Overnight? We Asked An Expert". Digital Trends. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Richardson, Melodie (24 June 2020). "Increasing battery capacity: going Si high". www.mewburn.com. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ "Si/C Composites for Battery Materials". www.acsmaterial.com. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ "Solid-state batteries are finally making their way out of the lab". Freethink. 27 July 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ "Smartphone boom lifts phone market in first quarter". Reuters. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "How to Fix 'No SIM Card Detected' Error on Android". Make Tech Easier. 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Android Overtakes Apple with 44% Worldwide Share of Mobile App Downloads". Allied Business Intelligence Research. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- ^ "Mobile Operating System Market Share Worldwide". StatCounter. Retrieved 18 April 2025.

- ^ Lynn, Natalie (10 March 2016). "The History and Evolution of Mobile Advertising". Gimbal. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Bodic, Gwenaël Le (8 July 2005). Mobile Messaging Technologies and Services: SMS, EMS and MMS. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-01451-6.

- ^ W3C Interview: Vision Mobile on the App Developer Economy with Matos Kapetanakis and Dimitris Michalakos Archived 29 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Global Smartphone Market Share: By Quarter". Counterpoint Research. 24 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Cheng, Roger. "Farewell Nokia: The rise and fall of a mobile pioneer". CNET.

- ^ a b "How the smartphone made Europe look stupid". the Guardian. 14 February 2010.

- ^ Mobility, Yomi Adegboye AKA Mister (5 February 2020). "Non-Chinese smartphones: These phones are not made in China - MobilityArena.com". mobilityarena.com.

- ^ "Operation Data". China Mobile. 31 August 2017.

- ^ Source: wireless intelligence

- ^ "Millions keep secret mobile". BBC News. 16 October 2001. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Brooks, Richard (13 August 2007). "Donated cell phones help battered women". The Press-Enterprise. Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Goodyear, Dana (7 January 2009). "Letter from Japan: I ♥ Novels". The New Yorker. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ Lynn, Jonathan. "Mobile phones help lift poor out of poverty: U.N. study". Reuters. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ "4 Ways Smartphones Can Save Live TV". Tvgenius.net. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Donner, Jonathan, and Steenson, Molly Wright. "Beyond the Personal and Private: Modes of Mobile Phone Sharing in Urban India." In The Reconstruction of Space and Time: Mobile Communication Practices, edited by Scott Campbell and Rich Ling, 231–250. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2008.

- ^ Hahn, Hans; Kibora, Ludovic (2008). "The Domestication of the Mobile Phone: Oral Society and New ICT in Burkina Faso". Journal of Modern African Studies. 46: 87–109. doi:10.1017/s0022278x07003084. S2CID 154804246.

- ^ "Branchless banking to start in Bali". The Jakarta Post. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Feig, Nancy (25 June 2007). "Mobile Payments: Look to Korea". banktech.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Ready, Sarah (10 November 2009). "NFC mobile phone set to explode". connectedplanetonline.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Tofel, Kevin C. (20 August 2010). "VISA Testing NFC Memory Cards for Wireless Payments". gigaom.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Tracking a suspect by mobile phone". BBC News. 3 August 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Miller, Joshua (14 March 2009). "Cell Phone Tracking Can Locate Terrorists – But Only Where It's Legal". Fox News. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Cecilia Kang (3 March 2011). "China plans to track cellphone users, sparking human rights concerns". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011.

- ^ McCullagh, Declan; Anne Broache (1 December 2006). "FBI taps cell phone mic as eavesdropping tool". CNet News. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Gibbs, Samuel (18 April 2016). "Your phone number is all a hacker needs to read texts, listen to calls and track you". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "The Secret Life Series – Environmental Impacts of Cell Phones". Inform, Inc. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "E-waste research group, Facts and figures". Griffith University. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Mobile Phone Waste and The Environment". Aussie Recycling Program. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Rujanavech, Charissa; Lessard, Joe; Chandler, Sarah; Shannon, Sean; Dahmus, Jeffrey; Guzzo, Rob (September 2016). "Liam – An Innovation Story" (PDF). Apple. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Adams, Mike "Plea Urges Anti-Theft Phone Tech" Archived 16 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine San Francisco Examiner 7 June 2013 p. 5

- ^ "Apple to add kill switches to help combat iPhone theft" by Jaxon Van Derbeken San Francisco Chronicle 11 June 2013 p. 1

- ^ "IMEIpro – free IMEI number check service". www.imeipro.info. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "How stolen phone blacklists will tamp down on crime, and what to do in the mean time". 27 November 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "How To Change IMEI Number". 1 July 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Is your mobile phone helping fund war in Congo?". The Daily Telegraph. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Children of the Congo who risk their lives to supply our mobile phones". The Guardian. 7 December 2012.

- ^ Brunwasser, Matthew (25 January 2012). "Kosher Phones For Britain's Orthodox Jews". Public Radio International.

- ^ Hirshfeld, Rachel (26 March 2012). "Introducing: A 'Kosher Phone' Permitted on Shabbat". Arutz Sheva.

- ^ "Quit Googling yourself and drive: About 20% of drivers using Web behind the wheel, study says". Los Angeles Times. 4 March 2011.

- ^ Atchley, Paul; Atwood, Stephanie; Boulton, Aaron (January 2011). "The Choice to Text and Drive in Younger Drivers: Behaviour May Shape Attitude". Accident Analysis and Prevention. 43 (1): 134–142. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2010.08.003. PMID 21094307.

- ^ "Text messaging not illegal but data clear on its peril". Democrat and Chronicle. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008.

- ^ de Waard, D., Schepers, P., Ormel, W. and Brookhuis, K., 2010, Mobile phone use while cycling: Incidence and effects on behaviour and safety, Ergonomics, Vol 53, No. 1, January 2010, pp. 30–42.

- ^ Copeland, Larry (12 November 2013). "Drivers still Web surfing while driving, survey finds". USA Today.

- ^ Burger, Christoph; Riemer, Valentin; Grafeneder, Jürgen; Woisetschläger, Bianca; Vidovic, Dragana; Hergovich, Andreas (2010). "Reaching the Mobile Respondent: Determinants of High-Level Mobile Phone Use Among a High-Coverage Group" (PDF). Social Science Computer Review. 28 (3): 336–349. doi:10.1177/0894439309353099. S2CID 61640965. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Drivers face new phone penalties". 22 January 2007 – via BBC News.

- ^ "Careless talk". 22 February 2007 – via BBC News.

- ^ "Illinois to ban texting while driving". CNN. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Steitzer, Stephanie (14 July 2010). "Texting while driving ban, other new Kentucky laws take effect today". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Distracted Driving Laws". Public Health Law Research. 15 July 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ 47 CFR 22.925. Retrieved 11 May 2025.

- ^ 14 CFR 91.21. Retrieved 11 May 2025.

- ^ "Qatar Flies First B787 with Inflight Connectivity". IFExpress. 19 November 2012. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Sherr, Lynn; Chris Kilmer (7 December 2007). "Cell Phones Are Dangerous in Flight: Myth, or Fact?". ABC News. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "In flight phone-free zone may end". CNN. 3 October 2004. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Cauley, Leslie (16 June 2005). "Cingular backs air cell ban". USA Today. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Nasar, Jack L.; Troyer, Dereck (21 March 2013). "Pedestrian injuries due to mobile phone use in public places" (PDF). Accident Analysis and Prevention. 57: 91–95. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2013.03.021. PMID 23644536. S2CID 8743434. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Grabar, Henry (28 July 2017). "The Absurdity of Honolulu's New Law Banning Pedestrians From Looking at Their Cellphones". Slate. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Heid, Markham (23 January 2024). "Walking and Using a Phone Is Bad for Your Health". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ Leo Benedictus (15 September 2014), "Chinese city opens 'phone lane' for texting pedestrians", The Guardian

- ^ David Chazan (14 June 2015), "Antwerp introduces 'text walking lanes' for pedestrians using mobile phones", Daily Telegraph, Paris

- ^ "Smuggled cellphones a growing problem in California Prisons". CBS. 17 October 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ Kevin Johnson (20 November 2008). "Smuggled cellphones flourish in prisons". USA Today. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (23 July 2003). "Hospital Cell Phone Death". Snopes. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Rachel C. Vreeman, Aaron E. Carroll, "Medical Myths", The British Medical Journal (now called The BMJ) 335:1288 (20 December 2007), doi:10.1136/bmj.39420.420370.25

- ^ "Definition of SCREEN TIME". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Stiglic, Neza; Viner, Russell M (3 January 2019). "Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: a systematic review of reviews". BMJ Open. 9 (1) e023191. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023191. PMC 6326346. PMID 30606703.

- ^ "This Place Just Made it Illegal to Give Kids Too Much Screen Time". Time. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Radesky, Jenny; Christakis, Dimitri (2016). "Media and Young Minds". Pediatrics. 138 (5): e20162591. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2591. PMID 27940793.

- ^ "Do mobile phones, 4G or 5G cause cancer?". Cancer Research UK. 8 February 2022.

- ^ Karipidis, Ken; Baaken, Dan; Loney, Tom; Blettner, Maria; Brzozek, Chris; Elwood, Mark; Narh, Clement; Orsini, Nicola; Röösli, Martin; Paulo, Marilia Silva; Lagorio, Susanna (30 August 2024). "The effect of exposure to radiofrequency fields on cancer risk in the general and working population: A systematic review of human observational studies – Part I: Most researched outcomes". Environment International. 191 108983. Bibcode:2024EnInt.19108983K. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2024.108983. hdl:10362/172700. ISSN 0160-4120. PMID 39241333.

- ^ Naeem, Zahid (October 2014). "Health risks associated with mobile phones use". International Journal of Health Sciences. 8 (4): V–VI. PMC 4350886. PMID 25780365.

- ^ Davis, Anna (18 May 2015). "Social media 'more stressful than exams'". London Evening Standard. p. 13.

- ^ "Cell phone users choosing fashion over function". NBC News. 14 October 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Pell, Alex, ed. (18 July 2023). "Test Bench: Fashion phones". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ Lasco, Gideon (22 October 2015). "The smartphone as status symbol". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ "iPhone, iPad are status symbols: Research". Deccan Chronicle. 9 July 2018.

- ^ Strat-Comm, Sailient (6 January 2018). "The evolution of emoji into culture". Medium. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Agar, Jon, Constant Touch: A Global History of the Mobile Phone, 2004 ISBN 1-84046-541-7

- Fessenden, R. A. (1908). "Wireless Telephony". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institution: 161–196. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Glotz, Peter & Bertsch, Stefan, eds. Thumb Culture: The Meaning of Mobile Phones for Society, 2005

- Goggin, Gerard, Global Mobile Media (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 176. ISBN 978-0-415-46918-0

- Jain, S. Lochlann (2002). "Urban Errands: The Means of Mobility". Journal of Consumer Culture. 2: 385–404. doi:10.1177/146954050200200305. S2CID 145577892.

- Katz, James E. & Aakhus, Mark, eds. Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance, 2002

- Kavoori, Anandam & Arceneaux, Noah, eds. The Cell Phone Reader: Essays in Social Transformation, 2006

- Kennedy, Pagan. Who Made That Cellphone? Archived 4 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 15 March 2013, p. MM19

- Kopomaa, Timo. The City in Your Pocket, Gaudeamus 2000

- Levinson, Paul, Cellphone: The Story of the World's Most Mobile Medium, and How It Has Transformed Everything!, 2004 ISBN 1-4039-6041-0

- Ling, Rich, The Mobile Connection: the Cell Phone's Impact on Society, 2004 ISBN 1-55860-936-9

- Ling, Rich and Pedersen, Per, eds. Mobile Communications: Re-negotiation of the Social Sphere, 2005 ISBN 1-85233-931-4

- Home page of Rich Ling

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. Mobile Communication: Essays on Cognition and Community, 2003

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. Mobile Learning: Essays on Philosophy, Psychology and Education, 2003

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. Mobile Democracy: Essays on Society, Self and Politics, 2003

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. A Sense of Place: The Global and the Local in Mobile Communication, 2005

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. Mobile Understanding: The Epistemology of Ubiquitous Communication, 2006

- Plant, Sadie, on the mobile – the effects of mobile telephones on social and individual life, 2001

- Rheingold, Howard, Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution, 2002 ISBN 0-7382-0861-2

- Singh, Rohit (April 2009). Mobile phones for development and profit: a win-win scenario (PDF). Overseas Development Institute. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

External links

[edit]- "How Cell Phones Work" at HowStuffWorks

- "The Long Odyssey of the Cell Phone", 15 photos with captions from Time magazine

- Cell Phone, the ring heard around the world – a video documentary by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

Mobile phone

View on GrokipediaTerminology

Definitions and Etymology

A mobile phone is a portable electronic device that enables wireless voice communication, as well as data transmission such as text messaging and internet access, by connecting to a cellular network via radio frequency signals.[17] This connection allows users to make and receive calls while moving within a coverage area, distinguishing it from fixed-line telephones that require wired infrastructure.[18] Modern mobile phones often integrate additional functionalities, including cameras, global positioning systems, and computing capabilities, evolving beyond basic telephony.[1] The term "mobile phone" originated as a descriptor for radio-telephones installed in vehicles, with early uses dating to the mid-20th century before portable handheld devices became prevalent.[19] "Mobile" derives from Latin mobilis, meaning "movable" or "capable of movement," reflecting the device's portability independent of fixed wiring.[20] "Phone" is a shortening of "telephone," from Greek tēle ("far") and phōnē ("voice" or "sound"), denoting a device for distant voice transmission.[21] In North America, the synonymous "cell phone" or "cellular phone" gained prominence due to the underlying network architecture, where service areas are divided into hexagonal "cells" to enable frequency reuse and efficient signal management—a concept patented by Bell Labs engineers in 1947.[22] This "cellular" terminology, borrowed from biological contexts referring to cell-like structures, underscores the geometric division of space rather than any organic analogy.[23] Regionally, "mobile phone" predominates outside the United States, while "cell phone" reflects the technical emphasis on cellular topology.[24]Historical Development

Precursors and Early Concepts

The development of mobile telephony built upon foundational advancements in radio communication and wireless transmission. Guglielmo Marconi's invention of wireless telegraphy in the late 1890s established the principle of transmitting signals without physical wires, initially for Morse code but laying groundwork for voice modulation techniques essential to telephony.[25] Early experiments in wireless telephony followed, including a 1908 U.S. patent granted for a wireless telephone device in Kentucky, which conceptualized battery-powered transmission of voice over radio waves, though practical implementation remained limited by technology constraints like signal interference and power requirements.[26] By the mid-20th century, mobile radio telephone systems emerged primarily as vehicle-mounted devices, serving as direct precursors to portable cellular networks. These systems used radio base stations connected to the public switched telephone network, enabling calls from cars via manual operator intervention or automated dialing. In June 1946, AT&T launched the first commercial mobile telephone service in St. Louis, Missouri, equipping vehicles with 80-pound units that accessed five available channels, supporting only a handful of simultaneous calls nationwide due to spectrum scarcity and single-transmitter architecture.[27] [28] Similar push-to-talk and dispatch radio systems proliferated for police, taxis, and emergency services, but voice telephony in cars expanded in Europe; for instance, Sweden introduced semi-automated mobile services in the 1940s, evolving to the fully automated Mobiltelefonisystem A (MTA) in 1956, which used vacuum tubes for improved reliability and supported up to 100 subscribers per base station.[29] A pivotal conceptual shift occurred in 1947 when Bell Laboratories engineer D.H. Ring proposed the cellular architecture in an internal memorandum, advocating a grid of low-power, hexagonal cells with reusable frequencies to dramatically increase capacity over monolithic high-power transmitters.[30] This idea addressed the inherent limitations of early mobile radio systems—such as frequency congestion, where U.S. networks handled fewer than 5,000 subscribers by the 1970s despite growing demand—by enabling handoff between cells and spectrum efficiency, principles that causal analysis attributes to solving bandwidth bottlenecks through spatial division rather than raw power increases.[31] These precursors highlighted the causal trade-offs in mobile communication: early vehicle-centric designs prioritized range over portability, while cellular concepts prioritized scalability, setting the stage for handheld devices by decoupling user mobility from fixed infrastructure power.[32]First Commercial Deployments (1970s-1990s)

The first commercial cellular telephone service launched in 1979 by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) in Tokyo, Japan, utilizing an analog 1G system initially for car-mounted phones.[33] This network marked the debut of automatic cellular technology, enabling mobile voice calls through frequency division multiple access (FDMA) in the 800-900 MHz bands, though early adoption was limited by high costs and bulky equipment.[34] In 1981, the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system became operational across Scandinavia, providing the first multinational analog cellular network spanning Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland.[35] NMT operated at 450 MHz initially, later expanding to 900 MHz for improved capacity, and supported roaming across borders, which facilitated early international mobile communication.[34] The United States deployed the Advanced Mobile Phone Service (AMPS) on October 13, 1983, in Chicago by Ameritech, following FCC approval of the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X as the first commercial handheld cellular phone earlier that year on September 21.[36][37] Priced at approximately $3,995, the DynaTAC weighed 790 grams, offered 30 minutes of talk time after a 10-hour charge, and relied on AMPS's analog FDMA technology in the 800 MHz band, rapidly expanding nationwide to over 100,000 subscribers by 1985.[36][38] Throughout the 1980s, analog 1G systems proliferated globally, including in the United Kingdom with the Total Access Communications System (TACS) in 1985 and in Australia in 1987, but these networks suffered from limited capacity, susceptibility to eavesdropping, and signal interference due to their unencrypted analog transmission.[39] By the late 1980s, demand outstripped analog infrastructure, prompting the development of digital standards. The transition to digital began in the early 1990s with the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), a 2G TDMA-based standard, first commercially launched on July 1, 1991, by Radiolinja in Finland.[40] This deployment enabled encrypted voice calls, SMS messaging, and higher capacity in the 900 MHz band, quickly spreading across Europe and beyond, with over 90 countries adopting GSM by the decade's end.[41] Early GSM handsets, such as those from Nokia, improved portability and battery life compared to 1G devices, laying the groundwork for widespread mobile adoption.[42]Digital Transition and Multimedia Era (1990s-2000s)

The transition from analog first-generation (1G) cellular networks to digital second-generation (2G) systems marked a pivotal advancement in mobile telephony during the 1990s, enabling improved voice quality, greater capacity, and the introduction of data services. The Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), a time-division multiple access (TDMA)-based standard developed primarily in Europe, saw its first commercial deployment on July 1, 1991, when Finland's Radiolinja network launched service, allowing the country's prime minister to make the inaugural GSM call.[43] In parallel, code-division multiple access (CDMA) technology, pioneered by Qualcomm, was publicly demonstrated on November 7, 1989, and standardized in the United States by 1993, offering superior spectral efficiency and resistance to interference compared to TDMA variants like Digital AMPS.[44] These 2G networks facilitated global roaming through SIM cards and spurred rapid adoption, with worldwide mobile subscriptions growing from approximately 11 million in 1990 to over 740 million by 2000.[45] A key innovation of 2G was the Short Message Service (SMS), which allowed short text communications over digital control channels. The first SMS message, "Merry Christmas," was sent on December 3, 1992, by engineer Neil Papworth from a computer to a Vodafone colleague's Orbitel 901 handset via the UK's GSM network.[46] SMS quickly became ubiquitous, driving interpersonal communication and generating significant revenue for carriers, though its 160-character limit stemmed from signaling protocol constraints rather than deliberate design for brevity. The late 1990s introduced rudimentary mobile data capabilities, transitioning devices toward multimedia functionality. The Wireless Application Protocol (WAP), released in 1999, enabled early mobile browsing of simplified web content like news and weather on compatible phones, though its clunky interface and limited bandwidth—often under 10 kbps—hindered widespread appeal outside niche markets.[47] In Japan, NTT DoCoMo's i-mode service, launched on February 22, 1999, pioneered packet-switched data access using compact HTML-like content, attracting over 40 million subscribers by 2003 through services like email, games, and vending machine control, demonstrating the viability of always-on mobile internet in high-density urban environments.[48] The 2000s expanded multimedia features, with devices incorporating color displays, polyphonic ringtones, and basic cameras. The Sharp J-SH04, released in November 2000 for Japan's J-Phone network, became the first commercial mobile phone with an integrated 0.11-megapixel CMOS camera, allowing users to capture and email low-resolution images via enhanced data services.[49] Email-focused devices like Research In Motion's BlackBerry, which debuted its first two-way pager in 1999 and integrated smartphones by 2002, emphasized push notifications and QWERTY keyboards for professionals, achieving peak market share through secure enterprise connectivity.[50] These developments, underpinned by 2G enhancements like General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) introduced around 2000, laid the groundwork for higher-speed 2.5G and 3G networks, though multimedia adoption remained constrained by battery life, screen size, and network costs until broadband proliferation.[51]Smartphone Dominance and Broadband Connectivity (2000s-2020s)