Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

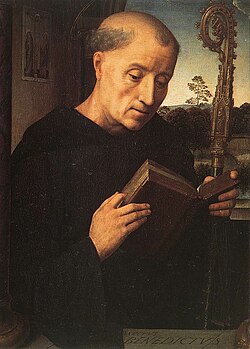

Benedict of Nursia

View on Wikipedia

Benedict of Nursia (Latin: Benedictus Nursiae; Italian: Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March 480 – 21 March 547), often known as Saint Benedict, was a Christian monk. He is famed in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Lutheran Churches, the Anglican Communion, and Old Catholic Churches.[3][4] In 1964, Pope Paul VI declared Benedict a patron saint of Europe.[5]

Key Information

Benedict founded twelve communities for monks at Subiaco in present-day Lazio, Italy (about 65 kilometres (40 mi) to the east of Rome), before moving southeast to Monte Cassino in the mountains of central Italy. The present-day Order of Saint Benedict emerged later and, moreover, is not an "order" as the term is commonly understood, but a confederation of autonomous congregations.[6]

Benedict's main achievement, his Rule of Saint Benedict, contains a set of rules for his monks to follow. Heavily influenced by the writings of John Cassian (c. 360 – c. 435), it shows strong affinity with the earlier Rule of the Master, but it also has a unique spirit of balance, moderation and reasonableness (ἐπιείκεια, epieíkeia), which persuaded most Christian religious communities founded throughout the Middle Ages to adopt it. As a result, Benedict's Rule became one of the most influential religious rules in Western Christendom. For this reason, Giuseppe Carletti regarded Benedict as the founder of Western Christian monasticism.[7]

Hagiography

[edit]Apart from a short poem attributed to Mark of Monte Cassino,[8] the only ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of Pope Gregory I's four-book Dialogues, thought to have been written in 593,[9] although the authenticity of this work is disputed.[10]

Gregory's account of Benedict's life, however, is not a biography in the modern sense of the word. It provides instead a spiritual portrait of the gentle, disciplined abbot. In a letter to Bishop Maximilian of Syracuse, Gregory states his intention for his Dialogues, saying they are a kind of floretum (an anthology, literally, 'flower garden') of the most striking miracles of Italian holy men.[11]

Gregory did not set out to write a chronological, historically anchored story of Benedict, but he did base his anecdotes on direct testimony. To establish his authority, Gregory explains that his information came from what he considered the best sources: a handful of Benedict's disciples who lived with him and witnessed his various miracles. These followers, he says, are Constantinus, who succeeded Benedict as Abbot of Monte Cassino, Honoratus, who was abbot of Subiaco when St. Gregory wrote his Dialogues, Valentinianus, and Simplicius.

In Gregory's day, history was not recognised as an independent field of study; it was a branch of grammar or rhetoric, and historia was an account that summed up the findings of the learned when they wrote what was, at that time, considered history.[12] Gregory's Dialogues, Book Two, then, an authentic medieval hagiography cast as a conversation between the Pope and his deacon Peter,[a] is designed to teach spiritual lessons.[9]

Early life

[edit]Benedict was the son of a Roman noble of Nursia,[9][13] the modern Norcia, in Umbria. According to Gregory's narrative, Benedict was born around 480, and the year in which he abandoned his studies and left home "was probably a few years before 500."[14]: 263

Benedict was sent to Rome to study, but was disappointed by the academic studies he encountered there. Seeking to flee the great city, he left with his nurse and settled in Enfide.[15] Enfide, which the tradition of Subiaco identifies with the modern Affile, is in the Simbruini mountains, about forty miles from Rome[13] and two miles from Subiaco.

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains and leading directly to Subiaco. The path continues to ascend, and the side of the ravine on which it runs becomes steeper until a cave is reached, above this point the mountain now rises almost perpendicularly; while on the right, it strikes in a rapid descent down to where, in Benedict's day, 500 feet (150 m) below, lay the blue waters of a lake. The cave has a large triangular-shaped opening and is about ten feet deep. On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, Romanus of Subiaco, whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and gave him the monk's habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years lived in this cave above the lake.[13]

Later life

[edit]Gregory tells little of Benedict's later life. He now speaks of Benedict no longer as a youth (puer), but as a man (vir) of God. Romanus, Gregory states, served Benedict in every way he could. The monk apparently visited him frequently, and on fixed days brought him food.[15]

During these three years of solitude, broken only by occasional communications with the outer world and by the visits of Romanus, Benedict matured both in mind and character, in knowledge of himself and of his fellow-man, and at the same time he became not merely known to, but secured the respect of, those about him; so much so that on the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighbourhood (identified by some with Vicovaro), the community came to him and begged him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that "their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together: yet, at length, overcome with their entreaty, he gave his consent".[10]: 3 The experiment failed; the monks tried to poison him. The legend goes that they first tried to poison his drink. He prayed a blessing over the cup and the cup shattered. Thus he left the group and went back to his cave at Subiaco.

There lived in the neighborhood a priest called Florentius who, moved by envy, tried to ruin him. He tried to poison him with poisoned bread. When he prayed a blessing over the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. From this time his miracles seem to have become frequent, and many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be under his guidance. Having failed by sending him poisonous bread, Florentius tried to seduce his monks with some prostitutes. To avoid further temptations, in about 530 Benedict left Subiaco.[16] He founded 12 monasteries in the vicinity of Subiaco, and, eventually, in 530 he founded the great Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, which lies on a hilltop between Rome and Naples.[17]

Veneration

[edit]Benedict died of a fever at Monte Cassino not long after his sister, Scholastica, and was buried in the same tomb. According to tradition, this occurred on 21 March 547.[18] He was named patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964.[19] In 1980, Pope John Paul II declared him co-patron of Europe, together with Cyril and Methodius.[20] Furthermore, he is the patron saint of speleologists.[21] On the island of Tenerife (Spain) he is the patron saint of fields and farmers.[22] An important romeria (Romería Regional de San Benito Abad) is held on this island in his honor, one of the most important in the country.[23]

In the pre-1970 General Roman Calendar, his feast is kept on 21 March, the day of his death according to some manuscripts of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum and that of Bede. Because on that date his liturgical memorial would always be impeded by the observance of Lent, the 1969 revision of the General Roman Calendar moved his memorial to 11 July, the date that appears in some Gallic liturgical books of the end of the 8th century as the feast commemorating his birth (Natalis S. Benedicti). There is some uncertainty about the origin of this feast.[24] Accordingly, on 21 March the Roman Martyrology mentions in a line and a half that it is Benedict's day of death and that his memorial is celebrated on 11 July, while on 11 July it devotes seven lines to speaking of him, and mentions the tradition that he died on 21 March.[25]

The Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates Saint Benedict on 14 March.[26]

The Lutheran Churches celebrate the Feast of Saint Benedict on July 11.[4]

The Anglican Communion has no single universal calendar, but a provincial calendar of saints is published in each province. In almost all of these, Saint Benedict is commemorated on 11 July. Benedict is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 11 July.[27]

Rule of Saint Benedict

[edit]Benedict wrote the Rule for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot. The Rule comprises seventy-three short chapters. Its wisdom is twofold: spiritual (how to live a Christocentric life on earth) and administrative (how to run a monastery efficiently).[17] More than half of the chapters describe how to be obedient and humble, and what to do when a member of the community is not. About one-fourth regulate the work of God (the "opus Dei"). One-tenth outline how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed. Benedictine asceticism is known for its moderation.[28]

Saint Benedict Medal

[edit]

This devotional medal originally came from a cross in honor of Saint Benedict. On one side, the medal has an image of Saint Benedict, holding the Holy Rule in his left hand and a cross in his right. There is a raven on one side of him, with a cup on the other side of him. Around the medal's outer margin are the words "Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur" ("May we be strengthened by his presence in the hour of our death"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials CSSML on the vertical bar which signify "Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux" ("May the Holy Cross be my light") and on the horizontal bar are the initials NDSMD which stand for "Non-Draco Sit Mihi Dux" ("Let not the dragon be my guide"). The initials CSPB stand for "Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti" ("The Cross of the Holy Father Benedict") and are located on the interior angles of the cross. Either the inscription "PAX" (Peace) or the Christogram "IHS" may be found at the top of the cross in most cases. Around the medal's margin on this side are the Vade Retro Satana initials VRSNSMV which stand for "Vade Retro Satana, Nonquam Suade Mihi Vana" ("Begone Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities") then a space followed by the initials SMQLIVB which signify "Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas" ("Evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thine own poison").[29]

This medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of Benedict's birth and is also called the Jubilee Medal; its exact origin, however, is unknown. In 1647, during a witchcraft trial at Natternberg near Metten Abbey in Bavaria, the accused women testified they had no power over Metten, which was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with the letters now found on St Benedict medals, but their meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was first approved by Pope Benedict XIV in his briefs of 23 December 1741 and 12 March 1742.[29]

Benedict has been also the motif of many collector's coins around the world. The Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders', issued on 13 March 2002 is one of them.[30]

Influence

[edit]

The early Middle Ages have been called "the Benedictine centuries".[31] In April 2008, Pope Benedict XVI discussed the influence St Benedict had on Western Europe. The pope said that "with his life and work St Benedict exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture" and helped Europe to emerge from the "dark night of history" that followed the fall of the Roman Empire.[32]

Benedict contributed more than anyone else to the rise of monasticism in the West. His Rule was the foundational document for thousands of religious communities in the Middle Ages.[33] To this day, The Rule of St. Benedict is the most common and influential Rule used by monasteries and monks, more than 1,400 years after its writing.

A basilica was built upon the birthplace of Benedict and Scholastica in the 1400s. Ruins of their familial home were excavated from beneath the church and preserved. The earthquake of 30 October 2016 completely devastated the structure of the basilica, leaving only the front facade and altar standing.[34][35]

Gallery

[edit]- See also Category:Paintings of Benedict of Nursia.

-

Saint Benedict and the cup of poison (Melk Abbey, Austria)

-

Small gold-coloured Saint Benedict crucifix

-

Both sides of a Saint Benedict Medal

-

Portrait (1926) by Herman Nieg (1849–1928); Heiligenkreuz Abbey, Austria

-

St. Benedict at the Death of St. Scholastica (c. 1250–60), Musée National de l'Age Médiévale, Paris, orig. at the Abbatiale of St. Denis

-

Statue in Einsiedeln, Switzerland

-

Statue in the Old Town district of Warsaw, Poland

-

Benedict holding a bound bundle of sticks representing the strength of monks who live in community[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For the various literary accounts, see Anonymous Monk of Whitby, The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great, tr. B. Colgrave (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 157, n. 110.

Citations

[edit]- ^

Lanzi, Fernando; Lanzi, Gioia (2004) [2003]. Saints and Their Symbols: Recog [Come riconoscere i santi]. Translated by O'Connell, Matthew J. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. p. 218. ISBN 9780814629703. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

Benedict of Nursia [...] Principal attributes: black monastic garb, staff, book with inscription: "Pray and Work."

- ^ "Saint Benedict of Nursia: The Iconography". Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Barry, Patrick (1995). St. Benedict and Christianity in England. Gracewing Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9780852443385.

- ^ a b Ramshaw, Gail (1983). Festivals and Commemorations in Evangelical Lutheran Worship (PDF). Augsburg Fortress. p. 299.

- ^

Barrely, Christine; Leblon, Saskia; Péraudin, Laure; Trieulet, Stéphane (23 March 2011) [2009]. "Benedict". The Little Book of Saints [Petit livre des saints]. Translated by Bell, Elizabeth. San Francisco: Chronicle Book. p. 34. ISBN 9780811877473. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

Declared the patron saint of Europe in 1964 by Pope Paul VI, Benedict is also the patron of farmers, peasants, and Italian architects.

- ^ Holder, Arthur G. (2009). Christian Spirituality: The Classics. Taylor & Francis. p. 70. ISBN 9780415776028. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

Today, tens of thousands of men and women throughout the world profess to live their lives according to Benedict's Rule. These men and women are associated with over two thousand Roman Catholic, Anglican, and ecumenical Benedictine monasteries on six continents.

- ^ Carletti, Giuseppe, Life of St. Benedict (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971).

- ^ "The Autumn Number 1921" (PDF). The Ampleforth Journal. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Ford, Hugh. "St. Benedict of Norcia." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 3 Mar. 2014". Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b Life and Miracles of St. Benedict (Book II, Dialogues), tr. Odo John Zimmerman, O.S.B. and Benedict , O.S.B. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980), p. iv.

- ^ See Ildephonso Schuster, Saint Benedict and His Times, Gregory A. Roettger, tr. (London: B. Herder, 1951), p. 2.

- ^ See Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, ed., Historiography in the Middle Ages (Boston: Brill, 2003), pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c Knowles, Michael David. "St. Benedict". Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Pope Gregory I, E. G. Gardner (ed.), The Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great: Re-edited with an Introduction and Notes (London & Boston: Philip Lee Warner, 1911), p. 263.

- ^ a b ""Saint Benedict, Abbot", Lives of Saints, John J. Crawley & Co., Inc". Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Bunson, M., Bunson, M., & Bunson, S., Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Saints (Huntington IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 2014), p. 125.

- ^ a b "St Benedict of Nursia", the British Library

- ^ "Saint Benedict of Norcia". Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "St. Benedict of Norcia". Catholic Online. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ "Egregiae Virtutis". Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009. Apostolic letter of Pope John Paul II, 31 December 1980 (in Latin)

- ^ Brewer's dictionary of phrase & fable. Cassell. p.953

- ^ Santos, J. T., "The Pilgrimage of San Benito in the 20th Century", lalagunaahora.com, June 15, 2015.

- ^ "Romería de San Benito Abad", Oficial de turismo de España

- ^ "Calendarium Romanum" (Libreria Editrice Vaticana), pp. 97 and 119

- ^ Martyrologium Romanum 199 (edito altera 2004); pages 188 and 361 of the 2001 edition (Libreria Editrice Vaticana ISBN 978-88-209-7210-3)

- ^ ""Orthodox Church in America: The Lives of the Saints, March 14th"". Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Saint Benedict", Franciscan Media

- ^ a b The Life of St Benedict Archived 20 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine, by St. Gregory the Great, Rockford, IL: TAN Books, pp 60–62.

- ^ Staff, "50 euro - The Christian Religious Orders", coin-database.com.

- ^ "Western Europe in the Middle Ages". Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ Benedict XVI, "Saint Benedict of Norcia" Homily given to a general audience at St. Peter's Square on Wednesday, 9 April 2008 "?". Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Stracke, Prof. J.R., "St. Benedict – Iconography", Augusta State University Archived 16 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Earthquake Blog - Monks of Norcia". Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ Bruton, F. B., & Lavanga, C., "Beer-Brewing Monks of Norcia Say Earthquake Destroys St. Benedict Basilica" Archived 8 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, NBC News, October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Saint Benedict of Nursia: The Iconography". Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Gardner, Edmund G., ed. (1911). The Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great. London and Boston: Philip Lee Warner, Publisher to the Medici Society Ltd. ISBN 9781889758947.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

External links

[edit]- "The Order of Saint Benedict". osb.org. (Institutional website of the Order of Saint Benedict)

- "Life and Miracles of Saint Benedict" (in English, Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 October 2004.

The Rule

[edit]- "A Benedictine Oblate Priest – The Rule in Parish Life". Archived from the original on 25 January 2009.

- St. Benedict's Rule for Monasteries at Project Gutenberg, translated by Leonard J. Doyle

- "The Holy Rule of St. Benedict". Translated by Boniface Verheyen.

Publications

[edit]- Gregory the Great. "Life and Miracles of St Benedict". Dialogues. Vol. Book 2. pp. 51–101.

- Guéranger, Prosper (1880). "The Medal or Cross of St. Benedict: Its Origin, Meaning, and Privileges".

- Works by Benedict of Nursia at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Benedict of Nursia at the Internet Archive

- Works by Benedict of Nursia at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Saint Benedict of Norcia, Patron of Poison Sufferers, Monks, And Many More". Archived from the original on 21 April 2014.

- Marett-Crosby, A., ed., The Benedictine Handbook (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2003).

- Publications by and about Benedict of Nursia in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

Iconography

[edit]- "Saint Benedict of Norcia". Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- "Founder Statue in St Peter's Basilica".

![Benedict holding a bound bundle of sticks representing the strength of monks who live in community[36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Saint_Andrew_and_Saint_Benedict_with_the_Archangel_Gabriel_%28left_panel%29_B35301.jpg/60px-Saint_Andrew_and_Saint_Benedict_with_the_Archangel_Gabriel_%28left_panel%29_B35301.jpg)