Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

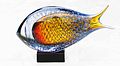

Studio glass

View on Wikipedia

Studio glass is the modern use of glass as an artistic medium to produce sculptures or three-dimensional artworks in the fine arts. The glass objects created are typically intended to make a sculptural or decorative statement, rather than fulfill functions (other than perhaps as vases) such as tableware. Though usage varies, the term is properly restricted to glass made as art in small workshops, typically with the personal involvement of the artist who designed the piece. This is in contrast to art glass, made by craftsmen in factories, and glass art, covering the whole range of glass with artistic interest made throughout history. Both art glass and studio glass originate in the 19th century, and the terms compare with studio pottery and art pottery, but in glass the term "studio glass" is mostly used for work made in the period beginning in the 1960s with a major revival in interest in artistic glassmaking.

Pieces are often unique, or made in a small limited edition. Their prices may range from a few hundred to hundreds of thousands of dollars (US).[1] For the largest installations, the prices are in the millions.[2]

Modern glass studios use a great variety of techniques in creating glass artworks, including:

History

[edit]From the 19th century, various types of fancy glass started to become significant branches of the decorative arts. Cameo glass was revived for the first time since the Romans, initially mostly used for pieces in a neo-classical style. The Art Nouveau movement in particular made great use of glass, with René Lalique, Émile Gallé, and Daum of Nancy important names in the first French wave of the movement, producing colored vases and similar pieces, often in cameo glass, and also using lustre techniques. Louis Comfort Tiffany in America specialized in secular stained glass, mostly of plant subjects, both in panels and his famous lamps. From the 20th century, some glass artists began to class themselves as sculptors working in glass and as part of the fine arts.

In the early 20th century, most glass production happened in factories. Even individual glassblowers making their own personalized designs would do their work in those large shared buildings. The idea of "art glass" grew – small decorative works in small production runs, often with designs or objects inside.

By the 1970s, there were good designs for smaller furnaces, and in the United States this gave rise to the "studio glass" movement of glassblowers, who worked outside of factories, often in their own buildings or studios. This coincided with a move towards smaller production runs of particular styles. This movement spread to other parts of the world as well.

Techniques used in modern studios

[edit]Modern glass studios use a great variety of techniques in creating their pieces. The ancient technique of blown glass, where a glassblower works at a furnace full of molten glass using metal rods and hand tools to blow and shape almost any form of glass, is one of the more popular ways to work. Most large hollow pieces are made this way, and it allows the artist to be improvisational as they create their work.

Another type is flame-worked glass, which uses torches and kilns in its production. The artist generally works at a bench using rods and tubes of glass, shaping with hand tools to create their work. Many forms can be achieved this way with little investment into money and space. Though the artist is somewhat limited in the size of the work that can be created, a great level of detail can be achieved with this technique. The paperweights by Paul Stankard are good examples of what can be achieved with flame-working techniques. In the 21st century, flame-worked glass became commonly used as adornments on functional items. The glass conductor's baton, commissioned by Chandler Bridges for Dr. Andre Thomas, is a clear example of flame-working being used to transform a traditional item into an artistic statement.

Cast glass can be done at the furnace, at the torch or in a kiln. Generally the artist makes a mold out of refractory, sand, or plaster and silica which can be filled with either clear glass or colored or patterned glass, depending on the techniques and effects desired. Large scale sculpture is usually created this way. Slumped glass and fused glass is similar to cast glass, but it is not done at as high of a temperature. Usually the glass is only heated enough to impress a shape or a texture onto the piece, or to stick several pieces of glass together without a glue.

The traditional technique of stained glass is still employed for the creation of studio glass. The artist cuts the glass into shapes and sets the pieces into lead cames which are soldered together. They artist can also use hot techniques in a kiln to create texture, patterns, or change the overall shape of the glass.

Etched glass is created by dipping glass that has an acid resistant pattern applied to its surface into an acid solution. Also an artist can engrave it by hand using wheels. Sandblasting can create a similar effect.

Cold glass is any glass worked without the use of heat. Glass may be cut, chiseled, sandblasted, and glued or bonded to form art objects ranging from small pieces to monumental sculpture.

Studio glass movement

[edit]The international studio glass movement originated in America, spreading to Europe, the United Kingdom, Australia and Asia. The emphasis of this movement was on the artist as the designer and maker of one-of-a-kind objects, in a small studio environment. This movement enabled the sharing of technical knowledge and ideas among artists and designers that, in industry, would not be possible.[3]

With the dominance of Modernism in the arts, there was a broadening of artistic media throughout the 20th century. Indeed, glass was part of the curriculum at art schools such as the Bauhaus. Frank Lloyd Wright produced glass windows considered by some as masterpieces not only of design, but of painterly composition as well. During the 1950s, studio ceramics and other craft media in the U.S. began to gain in popularity and importance, and American artists interested in glass looked for new paths outside industry.[3] Harvey Littleton, often referred to as the "Father of the Studio Glass Movement",[4] was inspired to develop studio glassblowing in America by the great glass being designed and made in Italy, Sweden and many other places, and by the pioneering work in ceramics of the California potter Peter Voulkos. Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino held the now-famous glass workshop at the Toledo Museum of Art in 1962. The goal was to melt glass in a small furnace so individual artists could use glass as an art medium in a non-industrial setting. This was the workshop that would stimulate the studio glass movement that spread around the world. Instead of the large, industrial settings of the past, a glass artist could now work with a small glass furnace in an individual setting and produce art from glass.

Modern regional glass art

[edit]Australia

[edit]The early glass movement (studio glass) in Australia was spurred on by a visit to Australia by American artist Bill Boysen, who toured the country in the early seventies with a mobile studio. Boysen traveled to Australia in 1974, where he promoted glass artistry by presenting a "revolutionary demonstration of glass blowing"[5] to a gathering of around 250 attendees. Boysen's mobile studio "successfully toured eight eastern states’ venues in ’74, thus greatly enhancing the credibility of hand crafted glass."[6] Boysen's visit is credited with helping "inspire a generation of [Australian] artists to work with glass and eventually led to the creation of the national glass art collection"[5] in Wagga Wagga, Australia. This important collection includes over 450 works of art and is "the most comprehensive public collection of Australian studio glass anywhere."[5] Since that time Australian glass has gained worldwide recognition with Adelaide in South Australia, hosting the International Glass Art Society Conference in 2005 on only its third occasion outside of the U.S. The Ranamok Glass Prize, presented every year from 1994 to 2014, promotes contemporary glass artists living in Australia and New Zealand.[7]

Belgium

[edit]Daniël Theys en Chris Miseur from the glass factory Theys & Miseur in Kortrijk-Dutsel, Belgium, which represent Belgian artistic glass work concerning the entire world. In 2015, John Moran (winner of Blown Away Season 3) co-founded Gent Glas, a public glass studio focused on introducing glass as an artistic medium to the general public. The studio has gone on to invite over 40 visiting artists from 13 different countries.

China

[edit]Although China has a very long tradition of glass art, studio glass was arguably first made by Loretta H. Yang and Chang Yi in 1987 at the first contemporary Chinese liuli art studio Liuligongfang. In 1997, Yang and Chang released their technique and procedure to the public. The Liuligongfang technique has since become a key cornerstone upon which contemporary Chinese liuli is built with Yang and Chang widely recognized as the pioneers and founders of contemporary Chinese liuli.[citation needed]

Italy

[edit]

Glass blowing began in the Roman Empire, and Italy has refined the techniques of glass blowing ever since. Until the very recent explosion of glass shops in Seattle (US), there were more on the Island of Murano (Italy) than anywhere else in world.[citation needed] The majority of the refined artistic techniques of glassblowing (e.g., incalmo, reticello, zanfirico, latticino) were developed there. Moreover, generations of blowers passed on their techniques to family members. Boys would begin working at the fornace (actually "furnace"—called "the factory" in English).[citation needed]

Japan

[edit]Japanese glass art which was inspired by the studio glass movement of the 1960s has a short history. The first independent glass studios of this period were built by Saburo Funakoshi and Makoto Ito, and Shinzo Kotani in separate places. Yoshihiko Takahashi and Hiroshi Yamano show their works at galleries throughout the world and are arguably Japan's glass artists of note. Yoichi Ohira has worked with great success in Murano with Italian gaffers. The small Pacific island Niijima, administered by Tokyo, has a renowned glass art center, built and run by Osamu and Yumiko Noda, graduates of Illinois State University, where they studied with Joel Philip Myers. Every autumn, the Niijima International Glass Art Festival takes place inviting top international glass artists for demonstrations and seminars. Emerging glass artists, such as Yukako Kojima and Tomoe Shizumu, were featured at the 2007 Glass Art Society exhibition space at the Pittsburgh Glass Center. Toshichi Iwata and Kyohei Fujita were noteworthy Japanese studio glass artists who worked before and after the studio glass movement of the 1960s. Both were active studio glass artists by the late 1940s. Fujita got his start working in the production part of Toshichi Iwata's studio which was founded in 1947.

- See also

Mexico

[edit]Mexico was the first country in Latin America to have a glass factory in the early sixteenth century brought by the Spanish conquerors. Although traditional glass in Mexico has prevailed over modern glass art, since the 1970s there have been a List of glass artists#Mexico that have given a place to that country in international glass art.

The Netherlands

[edit]Glass art in the Netherlands is mainly stimulated by the glass designing and glass blowing factory Royal Leerdam Crystal. Such notable designers as H.P. Berlage, Andries Copier and Sybren Valkema, Willem Heesen (Master Glassblower as well) had a major influence on Dutch glass art. Later the studio glass movement, inspired by the American Harvey Littleton and the new Workgroup Glass founded by Sybren Valkema at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam led to a new generation of glass artists.

United Kingdom

[edit]

Notable centres of glass production in the UK have been St. Helens in Merseyside (the home of Pilkington Glass and the site on which lead crystal glass was first produced by George Ravenscroft), Stourbridge in the Midlands and Sunderland in the North East. Sunderland is now home to the National Glass Centre which houses a specialist glass art course. St. Helens boasts a similar establishment but without the educational body attached. Perthshire in Scotland was known internationally for its glass paperweights. It has always hosted the best glass artists working on small scales, but closed its factory in Crieff, Scotland in January 2002.

Glass artists in the UK have a variety of exhibitions. The Scottish Glass Society hosts a yearly exhibition for members, the Guild of Glass Engravers exhibit every two years and the British Glass Biennale, begun in 2004 is now opening its third show.

British Glass Art owes much to the long history of craft. The majority of its glass blowers who operate small studio furnaces produce aesthetically beautiful though primarily functional objects. Technical skill as a blower is given as much importance as the artistic intent.

The Glasshouse, one of the first artist run UK studios, was established in 1967. Artists such as Jane Bruce, Steven Newell, Catherine Hough, Annette Meech, Christopher Williams and Simon Moore spent time working there until it closed its doors in the late 1990s. There are now a growing number of glass studios in the UK. Many specialize in production glassware while others concentrate on one off or limited edition pieces. An Arts Council funded, non-profit making organisation, the Contemporary Glass Society, founded in 1976 as British Artists in Glass, exists to promote and support the work of glass artists in the UK.[8]

Other glass organisations in the UK are The Guild of Glass Engravers, the Scottish Glass Society and Cohesion. Cohesion is a different sort of entity to the other organisations in that it was specifically founded to promote and develop glass art as a commercial concern. It organises trade events in and around the UK and at the international level. Originally it focused only on artists based the north east of England but has since expanded its remit to cover the whole of the UK.

In November 2007 the glass sculpture Model for a Hotel was unveiled as an exhibit on the fourth plinth of Trafalgar Square, London.

United States

[edit]The United States has had two phases of development in glass. The first, in the early and mid-1900s, started in the cities of Toledo, Ohio, and Corning, New York, where factories such as Fenton and Steuben were making both functional and artistic glass pieces. Toledo's rich history in glass goes back to the turn of the century when Libbey Glass, Owens-Illinois and Johns Manville led the world in the manufacturing of glass products. Their reputations earned Toledo the title of the "Glass Capital of the World." These industry leaders, along with the Toledo Museum of Art, sponsored the first glass workshop in 1961. This workshop would lead to a new movement in American studio glass.

The American Studio Glass Movement

[edit]The second, and most prominent, phase in American glass began in 1962, when then-ceramics professor Harvey Littleton and chemist Dominick Labino began the contemporary glassblowing movement. The impetus for the movement consisted of their two workshops at the Toledo Museum of Art, during which they began experimenting with melting glass in a small furnace and creating blown glass art. Littleton and Labino were the first to make molten glass feasible for artists in private studios. Harvey Littleton extended his influence through his own important artistic contributions and through his teaching and training, including many of the most important contemporary glass artists, including Marvin Lipofsky, Sam Herman (Britain), Fritz Dreisbach and Dale Chihuly.

In 1964, Tom McGlauchlin started one of the first accredited glass programs at the University of Iowa, and Marvin Lipofsky founded the university-level glass program at the University of California at Berkeley. In 1964, Dr. Robert C. Fritz founded a university-level glass program at San Jose State University in San Jose, California. As a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison under Harvey Littleton, Bill H. Boysen built the first glass studio at Penland School of Crafts, in Penland, North Carolina, in 1965. After graduating in 1966, he started the graduate glass program at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Illinois. Dale Chihuly initiated the glass program at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1969. Tom McGlauchlin joined the Toledo Museum of Art as Professor and Director of Glass in conjunction with the University of Toledo's Art program in 1971.

American Glass Schools and Studios

[edit]

The growth of studio glass led to the formation of glass schools and art studios located across the country. The largest concentrations of glass artists are located in Seattle, Ohio, New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey. San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles/Orange County and Corning, New York also have sizable concentrations of artists working in glass.

The Pilchuck Glass School near Seattle has become a mecca for glass artists from all over the world. Those who attend Pilchuck, either college students or established artists, have the opportunity to attend master classes and exchange skills and information in an environment dedicated solely to glass based arts.

Pittsburgh Glass Center in Pittsburgh has residency programs for artists working in glass, as well as a facility for artists to make use of for their works. Pittsburgh Glass Center offers classes to the public on glassblowing and many other forms of glass art. Philadelphia hosts a small array of glass studios for artists that use glass. Home to the National Liberty Museum (featuring all exhibits by international glass artists), Philadelphia hosts the non-profit P.I.P.E. program, with residencies for artists that use glass as well as metal, electroforming on glass, and bronze casting. The state of Pennsylvania has a long tradition of the production of industrial glass and its influence has quickly been absorbed by artists working in glass.

The Studio of The Corning Museum of Glass,[9] established in 1996, is a teaching facility in Corning, NY. Classes and workshops are held for new and experienced glassworkers and artists. The Studio's residency program brings artists from around the world to Corning for a month to work in The Studio facilities, where they can explore and develop new glassblowing techniques or expand on their current bodies of work; recipients of the Specialty Glass Residency include Beth Lipman, Mark Peiser, Karen LaMonte, and Anna Mlasowsky.[10] Artists working in The Studio have access to the collections of The Corning Museum of Glass, and benefit from the resources of the Rakow Research Library,[11] whose holdings cover the art and history of glass and glassmaking.

Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center,[12] located in the historic glass industry capital of Millville, New Jersey, is a nonprofit art and history education center that is home to the Museum of American Glass, which houses the largest collection of American glass objects in the world. The collection includes historical glass as well as contemporary work from some of the glass world's biggest names. In addition to the museum, WheatonArts operates a world-class glass studio under the creative direction of Hank Murta Adams.[13] The Creative Glass Center of America,[14] which is funded by WheatonArts and crucial to its mission of continuing Millville's legacy in the glass world, hosts a fellowship program exclusively for up-and-coming and mid-career artists working in glass. Well-known alumnae of the CGCA fellowship include Steve Tobin (1983) Kait Rhoads (1997 and 2008), Lino Tagliapietra (1989), Beth Lipman (2001), Gregory Nangle (2006), Deborah Czeresko (2006 and 2010), Angus Powers (2003), and Stephen Paul Day (1992, 1997, 2004, and 2009).[15]

San Jose State University glass program was started by Dr. Robert Fritz in 1964 and is the oldest educational studio glass program in California. Dr. Fritz died suddenly in 1986 and Mary B. White ran the program from 1986 to 2005.

Techniques and processes

[edit]Stained glass

[edit]Stained glass, such as the windows that are seen in churches, are windows that contain an element of painting in them. The window is designed. After the glass has been cut to shape, paint that contains ground glass is applied, so that, when it is fired in a kiln, the paint fuses onto the glass surface. Following this process, the sections of glass are placed together and held in place with lead came that is then soldered at the joints.

Leadlights and stained glass are manufactured in the same way, but leadlights do not contain any sections of glass that have been painted.

-

13th-century stained-glass windows in Sainte Chapelle, Paris

-

Modern stained-glass church window by Sarah Bristow

-

Leadlight artwork from 1977

Blown glass

[edit]Glassblowing is one of the most used technique for creating "art glass" and is still favoured by most of today's studio glass artists. This is because of the artist's intimacy with the material, and an almost infinite opportunity for creativity and variation at almost every stage of the process. Glassblowing can be used to create a multitude of shapes and can incorporate color through a wide range of techniques. Coloured glass can be gathered out of a crucible, clear glass can be rolled in powdered colored glass to coat the outside of a bubble, it can be rolled in chips of glass, it can be stretched into rods and incorporated through caneworking, or it can be layered, cut and fused into tiles, and incorporated into a bubble of glass for intricate patterns through murrine. "Blown glass" refers only to individually hand-made items but can include the use of moulds for shaping, ribbing, and spiking to produce decorative bubbles. Glass blown articles must be made of compatible glass or the stress in the piece will cause a failure.

-

Mid 20th Century Vortex Vase, by Robert C. Fritz, one of the founding fathers of the 1960s studio glass movement

-

Macro detail from a glass bowl blown at the World of Glass Museum. The white swirl was made by rolling the hot glass in glass powder.

Lampworking

[edit]Similar to glassblowing, Lampworking (also called flameworking or torchworking) is a style in which the artist manipulates glass with the use of a torch – rather than a blowpipe or blow tube – on a smaller scale. Once in a molten state, the glass is formed by blowing and shaping with tools and hand movements. Though typical lampworking art takes the form of beads, figurines, marbles, small vessels, Christmas tree ornaments, and other such things, it is also used to create scientific instruments as well as glass models of animals and botanical subjects.

-

A lampworked glass model of a cactus, part of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka's Glass Flowers collection at the Harvard Museum of Natural History

-

A sample of the Blaschka invertebrate models

-

Lampwork glass beads, unknown artist

Kiln-formed glass

[edit]Kiln formed glass is usually referred to as warm glass, and can be either made up from a single piece of glass that is slumped into or over a mould or different colours and sheets of glass fused together. The process of hot glass is highly scientific in that the types of glass and temperatures that they must be fired at is quite complicated operation to undertake correctly. Art glass that is kiln formed usually take the form of dishes, plates or tiles. Glass that is fused in a kiln must be of the same co-efficient of expansion (CoE). If glass that does not have the same CoE is used for fusing, the differing rates of contraction will cause minute stress fractures to form and, over time, these fractures will cause a piece to crack. The use of polarizing filters to inspect the work will determine if stress fractures are present.

Cold glass

[edit]Cold glass is worked by any method that does not use heat. Processes include sandblasting, cutting, sawing, chiseling, bonding and gluing.

Sandblasting

[edit]Glass can be decorated by sandblasting the surface of a piece in order to remove a layer of glass, thereby making a design stand out. Items that are sandblasted are usually thick slabs of glass into which a design has been carved by means of high pressure sandblasting. This technique provides a three-dimensional effect but is not suitable for toughened glass as the process could shatter it.

-

Sandblasted design in a window

-

Sculpture of an apple made of sandblasted glass

-

The interior of this artwork was sandblasted.

Copperfoil technique

[edit]The technique of using copperfoil is mainly used in the construction of smaller pieces such as Tiffany style lamps, and it was, in fact, frequently used by Louis Comfort Tiffany. It consists of wrapping cut sections of glass in a self-adhesive tape that is made out of thin copper foil. This technique requires a great deal of dexterity and is also very time-consuming. After the sections have been foiled, they are soldered together in order to form the item.

Gallery

[edit]-

Glass ball made by Tyler Hopkins at the Verrerie of Brehat in Brittany

-

"Reclining Dress Impression with Drapery," a life-sized glass sculpture by Karen LaMonte.

See also

[edit]- Cameo glass

- Caneworking

- Flameworking

- Fused glass

- Glass art

- Glass beadmaking

- Glass casting

- Glass disease

- Glass museums and galleries

- Glass tiles

- Glassblowing

- Glossary of Glass Art terms

- Knitted Glass

- Lampworking

- Mosaic

- Murano glass

- Murrine

- Paperweights

- Val Saint Lambert

- Vitreography (art form)

- List of glass artists

Sources

[edit]- The End William Warmus Glass Magazine Autumn 1995

- Warmus, William (2003). Fire and form : the art of contemporary glass. West Palm Beach, Fla. Seattle, WA: Norton Museum of Art Distributed by University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-943411-39-2. OCLC 52149531. Contains a detailed Chronological Bibliography of Contemporary Glass compiled with assistance of Beth Hylen

- Lynn, Martha (2004). American studio glass, 1960-1990. New York: Hudson Hills Press. ISBN 978-1-55595-239-6. OCLC 53939804.

- Oldknow, Tina (2020). Venice and American studio glass. Milano: Skira. ISBN 978-88-572-4387-0. OCLC 1200593335.

References

[edit]- ^ "Bonhams : 20th Century Decorative Arts". www.bonhams.com. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ^ "artnet.com Magazine Features – Art Market Guide 2003". www.artnet.com. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ^ a b "Corning Museum of Glass". Archived from the original on 2008-01-12. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ "Harvey K. Littleton". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ a b c "Blow-in Bill leaves locals glassy-eyed." Weekly Times (Australia), 31 August 2005: 95.

- ^ Skillitzi, Stephen (16 January 2009). "Australian Glass Pioneers". Glass Central Canberra. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "News: Kathryn Wightman wins the 2014 (and final) Ranamok Glass Prize". Bullseye Gallery. Bullseye Gallery. 12 August 2014. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "The Contemporary Glass Society".

- ^ "The Studio". cmog.org.

- ^ "Specialty Glass Residency | Corning Museum of Glass". www.cmog.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- ^ "Rakow Research Library". cmog.org.

- ^ "WheatonArts » Explore, Experience, Discover". Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center.

- ^ "WheatonArts - Hank Murta Adams". Archived from the original on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ^ "WheatonArts - Creative Glass Center of America". Archived from the original on 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ^ "Past Fellows". Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center. WheatonArts. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Studio glass in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1996.

External links

[edit]Studio glass

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Characteristics

Studio glass refers to the modern practice of individual artists or small teams designing and creating unique or limited-edition sculptural and functional glass artworks in personal studios, employing hands-on methods rather than industrial factory production.[7] This approach emerged as a distinct medium within the fine arts in the post-World War II era, shifting glass from a primarily utilitarian material to one valued for personal artistic expression.[8] At its core, studio glass emphasizes one-of-a-kind pieces that prioritize individual creativity and innovation over mass production, allowing artists to explore the material's inherent qualities such as transparency, fluidity, and light refraction.[9] It integrates traditional glassmaking craftsmanship—rooted in techniques like blowing and casting—with contemporary aesthetics, often resulting in bold colors, organic shapes, and interdisciplinary forms that blend sculpture, design, and conceptual art.[10] This individualistic nature fosters experimentation, where the artist's direct involvement in the process imbues each work with unique character and intent.[8] Typical forms in studio glass include vessels that merge functionality with artistic form, abstract sculptures that exploit glass's structural versatility, and large-scale installations that transform spaces through light and color.[10] For instance, free-blown vessels and cast glass pieces often highlight the medium's ability to balance utility and aesthetic appeal, while monumental installations push the boundaries of scale and environmental interaction.[9] These works underscore studio glass's role in elevating the material to fine art status.[8]Distinction from Other Glass Practices

Studio glass distinguishes itself from industrial glass production primarily through its emphasis on individual artistic intent and small-scale craftsmanship, in contrast to the mass-production and functional focus of factory methods. In studio glass, a single artist typically oversees the entire process from conception to execution, allowing for unique, limited-edition works that prioritize expressive content over uniformity. This approach enables experimentation with form, color, and technique in personal studios, often using modest equipment like small furnaces. Industrial glass, by comparison, involves repetitive, mechanized processes in large factories where teams execute designs for high-volume output, such as consumer goods like tumblers or bottles, with efficiency and standardization as core principles.[11][12] The following table summarizes key differences between studio and industrial glass production:| Aspect | Studio Glass | Industrial Glass |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | Small-scale, individual or small teams | Large-scale, high-volume |

| Process | Handcrafted, artisanal | Automated, mechanized |

| Intent | Artistic expression, unique pieces | Functional, uniform products |

| Output | Limited editions, sculptural focus | Mass-produced for utility |