Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Surplus value

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxian economics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cost of the materials, plant and labour power. The concept originated in Ricardian socialism, with the term "surplus value" itself being coined by William Thompson in 1824; however, it was not consistently distinguished from the related concepts of surplus labor and surplus product. The concept was subsequently developed and popularized by Karl Marx.[1] Marx's formulation is the standard sense and the primary basis for further developments, though how much of Marx's concept is original and distinct from the Ricardian concept is disputed (see § Origin). Marx's term is the German word "Mehrwert", which simply means value added (sales revenue minus the cost of materials used up), and is cognate to English "more worth".

It is a major concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy, and, like all of Marx's economic theories, lies outside the economic mainstream.[2] Conventionally, value-added is equal to the sum of gross wage income and gross profit income. However, Marx uses the term Mehrwert to describe the yield, profit or return on production capital invested, i.e. the amount of the increase in the value of capital. Hence, Marx's use of Mehrwert has always been translated as "surplus value", distinguishing it from "value-added". According to Marx's theory, surplus value is equal to the new value created by workers in excess of their own labor-cost, which is appropriated by the capitalist as profit when products are sold.[3][4] Marx thought that the gigantic increase in wealth and population from the 19th century onwards was mainly due to the competitive striving to obtain maximum surplus-value from the employment of labor, resulting in an equally gigantic increase of productivity and capital resources. To the extent that increasingly the economic surplus is convertible into money and expressed in money, the amassment of wealth is possible on a larger and larger scale (see capital accumulation and surplus product). The concept is closely connected to producer surplus.

Origin

[edit]By the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century the French physiocrats were already writing on the hypothesis that surplus value that was being extracted from labor by "the employer, the owner, and all exploiters" although they used the term net product.[5] The concept of surplus value continued to be developed under Adam Smith who also used the term "net product" while his successors the Ricardian socialists, began using the term "surplus value" decades later after its coinage by William Thompson in 1824:

Two measures of the value of this use, here present themselves; the measure of the laborer, and the measure of the capitalist. The measure of the laborer consists in the contribution of such sums as would replace the waste and value of the capital by the time it would be consumed, with such added compensation to the owner and superintendent of it as would support him in equal comfort with the more actively employed productive laborers. The measure of the capitalist, on the contrary, would be the additional value produced by the same quantity of labor in consequence of the use of the machinery or other capital; the whole of such surplus value to be enjoyed by the capitalist for his superior intelligence and skill in accumulating and advancing to the laborers his capital or the use of it.

— William Thompson, An Inquiry into the Principles of the Distribution of Wealth (1824), p. 128 (2nd ed.), emphasis added

William Godwin and Charles Hall are also credited as earlier developers of the concept. Early authors also used the terms "surplus labor" and "surplus produce" (in Marx's language, surplus product), which have distinct meanings in Marxian economics: surplus labor produces surplus product, which has surplus value. Some authors consider Marx as completely borrowing from Thompson, notably Anton Menger:

... Marx is completely under the influence of the earlier English socialists, and more particularly of William Thompson. ... [T]he whole theory of surplus value, its conception, its name, and the estimates of its amounts are borrowed in all essentials from Thompson's writings.

...

Cf. Marx, Das Kapital, English trans. 1887, pp. 156, 194, 289, with Thompson, Distribution of Wealth, p. 163; 2nd ed. p. 125. ... The real discovers of the theory of surplus value are Godwin, Hall, and especially W. Thompson.

— Anton Menger, The Right to the Whole Produce of Labour (1886),[6] p. 101

This claim of priority has been vigorously contested, notably in an article by Friedrich Engels, completed by Karl Kautsky and published anonymously in 1887, reacting to and criticizing Menger in a review of his The Right to the Whole Produce of Labour, arguing that there is nothing in common but the term "surplus value" itself.[7]

An intermediate position acknowledges the early development by Ricardian socialists and others, but credits Marx with substantial development. For example:[8][a]

What is original in Marx is the explanation of the manner in which surplus value is produced.

— John Spargo, Socialism (1906)

Johann Karl Rodbertus developed a theory of surplus value in the 1830s and 1840s, notably in Zur Erkenntnis unserer staatswirthschaftlichen Zustände (Toward an appreciation of our economic circumstances, 1842), and claimed earlier priority to Marx, specifically to have "shown practically in the same way as Marx, only more briefly and clearly, the source of the surplus value of the capitalists". The debate, taking the side of Marx's priority, is detailed in the Preface to Capital, Volume II by Engels.

Marx first elaborated his doctrine of surplus value in 1857–58 manuscripts of A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), following earlier developments in his 1840s writings.[9] It forms the subject of his 1862–63 manuscript Theories of Surplus Value (which was subsequently published as Capital, Volume IV), and features in his Capital, Volume I (1867).

Theory

[edit]The problem of explaining the source of surplus value is expressed by Friedrich Engels as follows:

Whence comes this surplus-value? It cannot come either from the buyer buying the commodities under their value, or from the seller selling them above their value. For in both cases the gains and the losses of each individual cancel each other, as each individual is in turn buyer and seller. Nor can it come from cheating, for though cheating can enrich one person at the expense of another, it cannot increase the total sum possessed by both, and therefore cannot augment the sum of the values in circulation. (...) This problem must be solved, and it must be solved in a purely economic way, excluding all cheating and the intervention of any force — the problem being: how is it possible constantly to sell dearer than one has bought, even on the hypothesis that equal values are always exchanged for equal values?[10]

Marx's solution was first to distinguish between labor-time worked and labor power, and secondly to distinguish between absolute surplus value and relative surplus value. A worker who is sufficiently productive can produce an output value greater than what it costs to hire them. Although their wage seems to be based on hours worked, in an economic sense this wage does not reflect the full value of what the worker produces. Effectively it is not labour which the worker sells, but their capacity to work.

Imagine a worker who is hired for an hour and paid $10 per hour. Once in the capitalist's employ, the capitalist can have them operate a boot-making machine with which the worker produces $10 worth of work every 15 minutes. Every hour, the capitalist receives $40 worth of work and only pays the worker $10, capturing the remaining $30 as gross revenue. Once the capitalist has deducted fixed and variable operating costs of (say) $20 (leather, depreciation of the machine, etc.), he is left with $10. Thus, for an outlay of capital of $30, the capitalist obtains a surplus value of $10; their capital has not only been replaced by the operation, but also has increased by $10.

This "simple" exploitation characterizes the realization of absolute surplus value, which is then claimed by the capitalist. The worker cannot capture this benefit directly because they have no claim to the means of production (e.g. the boot-making machine) or to its products, and his capacity to bargain over wages is restricted by laws and the supply/demand for wage labour. This form of exploitation was well understood by pre-Marxian Socialists and left-wing followers of Ricardo, such as Proudhon, and by early labor organizers, who sought to unite workers in unions capable of collective bargaining, in order to gain a share of profits and limit the length of the working day.[11]

Relative surplus value is not created in a single enterprise or site of production. It arises instead from the total relation between multiple enterprises and multiple branches of industry when the necessary labor-time of production is reduced, effecting a change in the value of labor-power. For example, when new technology or new business practices increase the productivity of labor a capitalist already employs, or when the commodities necessary for workers' subsistence fall in value, the amount of socially necessary labor-time is decreased, the value of labor-power is reduced, and a relative surplus value is realized as profit for the capitalist, increasing the overall general rate of surplus value in the total economy:

The surplus-value produced by prolongation of the working day, I call absolute surplus-value. On the other hand, the surplus-value arising from the curtailment of the necessary labour-time, and from the corresponding alteration in the respective lengths of the two components of the working day, I call relative surplus-value.

In order to effect a fall in the value of labour-power, the increase in the productiveness of labour must seize upon those branches of industry whose products determine the value of labour-power, and consequently either belong to the class of customary means of subsistence, or are capable of supplying the place of those means. But the value of a commodity is determined, not only by the quantity of labour which the labourer directly bestows upon that commodity, but also by the labour contained in the means of production. For instance, the value of a pair of boots depends not only on the cobbler’s labour, but also on the value of the leather, wax, thread, &c. Hence, a fall in the value of labour-power is also brought about by an increase in the productiveness of labour, and by a corresponding cheapening of commodities in those industries which supply the instruments of labour and the raw material, that form the material elements of the constant capital required for producing the necessaries of life.

— Marx, Capital Vol. 1, ch. 12, "The Concept of Relative Surplus-Value"[12]

Definition

[edit]Total surplus-value in an economy (Marx refers to the mass or volume of surplus-value) is basically equal to the sum of net distributed and undistributed profit, net interest, net rents, net tax on production and various net receipts associated with royalties, licensing, leasing, certain honorariums etc. (see also value product). Of course, the way generic profit income is grossed and netted in social accounting may differ somewhat from the way an individual business does that (see also Operating surplus).

Marx's own discussion focuses mainly on profit, interest and rent, largely ignoring taxation and royalty-type fees which were proportionally very small components of the national income when he lived. Over the last 150 years, however, the role of the state in the economy has increased in almost every country in the world. Around 1850, the average share of government spending in GDP (See also Government spending) in the advanced capitalist economies was around 5%; in 1870, a bit above 8%; on the eve of World War I, just under 10%; just before the outbreak of World War II, around 20%; by 1950, nearly 30%; and today the average is around 35–40%. (see for example Alan Turner Peacock, "The growth of public expenditure", in Encyclopedia of Public Choice, Springer 2003, pp. 594–597).

Interpretations

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Outline |

Surplus-value may be viewed in five ways:

- As a component of the new value product, which Marx himself defines as equal to the sum of labor costs in respect of capitalistically productive labor (variable capital) and surplus-value. In production, he argues, the workers produce a value equal to their wages plus an additional value, the surplus-value. They also transfer part of the value of fixed assets and materials to the new product, equal to economic depreciation (consumption of fixed capital) and intermediate goods used up (constant capital inputs). Labor costs and surplus-value are the monetary valuations of what Marx calls the necessary product and the surplus product, or paid labour and unpaid labour.

- Surplus-value can also be viewed as a flow of net income appropriated by the owners of capital in virtue of asset ownership, comprising both distributed personal income and undistributed business income. In the whole economy, this will include both income directly from production and property income.

- Surplus-value can be viewed as the source of society's accumulation fund or investment fund; part of it is re-invested, but part is appropriated as personal income, and used for consumptive purposes by the owners of capital assets (see capital accumulation); in exceptional circumstances, part of it may also be hoarded in some way. In this context, surplus value can also be measured as the increase in the value of the stock of capital assets through an accounting period, prior to distribution.

- Surplus-value can be viewed as a social relation of production, or as the monetary valuation of surplus-labour – a sort of "index" of the balance of power between social classes or nations in the process of the division of the social product.

- Surplus-value can, in a developed capitalist economy, be viewed also as an indicator of the level of social productivity that has been reached by the working population, i.e. the net amount of value it can produce with its labour in excess of its own consumption requirements.

Equalization of rates

[edit]Marx believed that the long-term historical tendency would be for differences in rates of surplus value between enterprises and economic sectors to level out, as Marx explains in two places in Capital Vol. 3:

If capitals that set in motion unequal quantities of living labour produce unequal amounts of surplus-value, this assumes that the level of exploitation of labour, or the rate of surplus-value, is the same, at least to a certain extent, or that the distinctions that exist here are balanced out by real or imaginary (conventional) grounds of compensation. This assumes competition among workers, and an equalization that takes place by their constant migration between one sphere of production and another. Assume a general rate of surplus value of this kind, as a tendency, like all economic laws, as a theoretical simplification; but in any case this is in practice an actual presupposition of the capitalist mode of production, even if inhibited to a greater or lesser extent by practical frictions that produce more or less significant local differences, such as the settlement laws for agricultural labourers in England, for example. In theory, we assume that the laws of the capitalist mode of production develop in their pure form. In reality, this is only an approximation; but that approximation is all the more exact, the more the capitalist mode of production is developed and the less it is adulterated by survivals of earlier economic conditions with which it is amalgamated – Capital Vol. 3, ch. 10, Pelican edition p. 275.[13]

Hence, he assumed a uniform rate of surplus value in his models of how surplus value would be shared out under competitive conditions.

Appropriation from production

[edit]Both in Das Kapital and in preparatory manuscripts such as the Grundrisse and Results of the immediate process of production, Marx asserts that commerce by stages transforms a non-capitalist production process into a capitalist production process, integrating it fully into markets, so that all inputs and outputs become marketed goods or services. When that process is complete, according to Marx, the whole of production has become simultaneously a labor process creating use-values and a valorisation process creating new value, and more specifically a surplus-value appropriated as net income (see also capital accumulation).[citation needed]

Marx contends that the whole purpose of production in this situation becomes the growth of capital; i.e. that production of output becomes conditional on capital accumulation.[citation needed] If production becomes unprofitable, capital will be withdrawn from production sooner or later.

The implication is that the main driving force of capitalism becomes the quest to maximise the appropriation of surplus-value augmenting the stock of capital. The overriding motive behind efforts to economise resources and labor would thus be to obtain the maximum possible increase in income and capital assets ("business growth"), and provide a steady or growing return on investment.

Absolute vs. relative

[edit]According to Marx, absolute surplus value is obtained by increasing the amount of time worked per worker in an accounting period.[14] Marx talks mainly about the length of the working day or week, but in modern times the concern is about the number of hours worked per year.

In many parts of the world, as productivity rose, the workweek decreased from 60 hours to 50, 40 or 35 hours.

Relative surplus value is obtained mainly by:

- Reducing wages[15] — this can only go to a certain point, because if wages fall below the ability of workers to purchase their means of subsistence, they will be unable to reproduce themselves and the capitalists will not be able to find sufficient labor power.

- Reducing the cost of wage-goods by various means, so that wage increases can be curbed.[16]

- Increasing the productivity and intensity[citation needed] of labour generally, through mechanisation and rationalisation, yielding a bigger output per hour worked.

The attempt to extract more and more surplus-value from labor on the one side, and on the other side the resistance to this exploitation, are according to Marx at the core of the conflict between social classes, which is sometimes muted or hidden, but at other times erupts in open class warfare and class struggle.

Production versus realisation

[edit]Marx distinguished sharply between value and price, in part because of the sharp distinction he draws between the production of surplus-value and the realisation of profit income (see also value-form). Output may be produced containing surplus-value (valorisation), but selling that output (realisation) is not at all an automatic process.

Until payment from sales is received, it is uncertain how much of the surplus-value produced will actually be realised as profit from sales. So, the magnitude of profit realised in the form of money and the magnitude of surplus-value produced in the form of products may differ greatly, depending on what happens to market prices and the vagaries of supply and demand fluctuations. This insight forms the basis of Marx's theory of market value, prices of production and the tendency of the rate of profit of different enterprises to be levelled out by competition.

In his published and unpublished manuscripts, Marx went into great detail to examine many different factors which could affect the production and realisation of surplus-value. He regarded this as crucial for the purpose of understanding the dynamics and dimensions of capitalist competition, not just business competition but also competition between capitalists and workers and among workers themselves. But his analysis did not go much beyond specifying some of the overall outcomes of the process.

His main conclusion though is that employers will aim to maximise the productivity of labour and economise on the use of labour, to reduce their unit-costs and maximise their net returns from sales at current market prices; at a given ruling market price for an output, every reduction of costs and every increase in productivity and sales turnover will increase profit income for that output. The main method is mechanisation, which raises the fixed capital outlay in investment.

In turn, this causes the unit-values of commodities to decline over time, and a decline of the average rate of profit in the sphere of production occurs, culminating in a crisis of capital accumulation, in which a sharp reduction in productive investments combines with mass unemployment, followed by an intensive rationalisation process of take-overs, mergers, fusions, and restructuring aiming to restore profitability.

Relation to taxation

[edit]

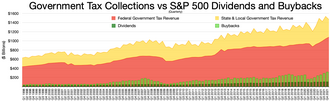

State tax revenue

Federal tax revenue

S&P 500 Stock buyback

S&P 500 Dividends

In general, business leaders and investors are hostile to any attempts to encroach on total profit volume, especially those of government taxation.[citation needed] The lower taxes are, other things being equal, the bigger the mass of profit that can be distributed as income to private investors. It was tax revolts that originally were a powerful stimulus motivating the bourgeoisie to wrest state power from the feudal aristocracy at the beginning of the capitalist era.[citation needed]

In reality, of course, a substantial portion of tax money is also redistributed to private enterprise in the form of government contracts and subsidies.[citation needed] Capitalists may therefore be in conflict among themselves about taxes, since what is a cost to some, is a source of profit to others.[citation needed] Marx never analysed all this in detail; but the concept of surplus value will apply mainly to taxes on gross income (personal and business income from production) and on the trade in products and services.[citation needed] Estate duty for example rarely contains a surplus value component, although profit could be earned in the transfer of the estate.[citation needed]

Generally, Marx seems to have regarded taxation imposts as a "form" which disguised real product values. Apparently following this view, Ernest Mandel in his 1960 treatise Marxist Economic Theory refers to (indirect) taxes as "arbitrary additions to commodity prices". But this is something of a misnomer, and disregards that taxes become part of the normal cost-structure of production. In his later treatise on late capitalism, Mandel astonishingly hardly mentions the significance of taxation at all, a very serious omission from the point of view of the real world of modern capitalism since taxes can reach a magnitude of a third, or even half of GDP (see E. Mandel, Late Capitalism. London: Verso, 1975).For example in the United Kingdom alone 75% of all taxation revenue comes from just three taxes Income tax, National insurance and VAT which in reality is 75% of the GDP of the country.

Relation to the circuits of capital

[edit]Generally, Marx focused in Das Kapital on the new surplus-value generated by production, and the distribution of this surplus value. In this way, he aimed to reveal the "origin of the wealth of nations" given a capitalist mode of production. However, in any real economy, a distinction must be drawn between the primary circuit of capital, and the secondary circuits. To some extent, national accounts also do this.

The primary circuit refers to the incomes and products generated and distributed from productive activity (reflected by GDP). The secondary circuits refer to trade, transfers and transactions occurring outside that sphere, which can also generate incomes, and these incomes may also involve the realisation of a surplus-value or profit.

It is true that Marx argues no net additions to value can be created through acts of exchange, economic value being an attribute of labour-products (previous or newly created) only. Nevertheless, trading activity outside the sphere of production can obviously also yield a surplus-value which represents a transfer of value from one person, country or institution to another.

A very simple example would be if somebody sold a second-hand asset at a profit. This transaction is not recorded in gross product measures (after all, it isn't new production), nevertheless a surplus-value is obtained from it. Another example would be capital gains from property sales. Marx occasionally refers to this kind of profit as profit upon alienation, alienation being used here in the juridical, not sociological sense. By implication, if we just focused on surplus-value newly created in production, we would underestimate total surplus-values realised as income in a country. This becomes obvious if we compare census estimates of income & expenditure with GDP data.

This is another reason why surplus-value produced and surplus-value realised are two different things, although this point is largely ignored in the economics literature. But it becomes highly important when the real growth of production stagnates, and a growing portion of capital shifts out of the sphere of production in search of surplus-value from other deals.

Nowadays the volume of world trade grows significantly faster than GDP, suggesting to Marxian economists such as Samir Amin that surplus-value realised from commercial trade (representing to a large extent a transfer of value by intermediaries between producers and consumers) grows faster than surplus-value realised directly from production.

Thus, if we took the final price of a good (the cost to the final consumer) and analysed the cost structure of that good, we might find that, over a period of time, the direct producers get less income and intermediaries between producers and consumers (traders) get more income from it. That is, control over the access to a good, asset or resource as such may increasingly become a very important factor in realising a surplus-value. In the worst case, this amounts to parasitism or extortion. This analysis illustrates a key feature of surplus value which is that it accumulated by the owners of capital only within inefficient markets because only inefficient markets – i.e. those in which transparency and competition are low – have profit margins large enough to facilitate capital accumulation. Ironically, profitable – meaning inefficient – markets have difficulty meeting the definition a free market because a free market is to some extent defined as an efficient one: one in which goods or services are exchanged without coercion or fraud, or in other words with competition (to prevent monopolistic coercion) and transparency (to prevent fraud).

Measurement

[edit]The first attempt to measure the rate of surplus-value in money-units was by Marx himself in chapter 9 of Das Kapital, using factory data of a spinning mill supplied by Friedrich Engels (though Marx credits "a Manchester spinner"). Both in published and unpublished manuscripts, Marx examines variables affecting the rate and mass of surplus-value in detail.

Some Marxian economists argue that Marx thought the possibility of measuring surplus value depends on the publicly available data. We can develop statistical indicators of trends, without mistakenly conflating data with the real thing they represent, or postulating "perfect measurements or perfect data" in the empiricist manner.

Since early studies by Marxian economists like Eugen Varga, Charles Bettelheim, Joseph Gillmann, Edward Wolff and Shane Mage, there have been numerous attempts by Marxian economists to measure the trend in surplus-value statistically using national accounts data. The most convincing modern attempt is probably that of Anwar Shaikh and Ahmet Tonak.[17]

Usually this type of research involves reworking the components of the official measures of gross output and capital outlays to approximate Marxian categories, in order to estimate empirically the trends in the ratios thought important in the Marxian explanation of capital accumulation and economic growth: the rate of surplus-value, the organic composition of capital, the rate of profit, the rate of increase in the capital stock, and the rate of reinvestment of realised surplus-value in production.

The Marxian mathematicians Emmanuel Farjoun and Moshé Machover argue that "even if the rate of surplus value has changed by 10–20% over a hundred years, the real problem [to explain] is why it has changed so little" (quoted from The Laws of Chaos: A Probabilistic Approach to Political Economy (1983), p. 192). The answer to that question must, in part, be sought in artifacts (statistical distortion effects) of data collection procedures. Mathematical extrapolations are ultimately based on the data available, but that data itself may be fragmentary and not the "complete picture".

Different conceptions

[edit]In neo-Marxist thought, Paul A. Baran for example substitutes the concept of "economic surplus" for Marx's surplus value. In a joint work, Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy define the economic surplus as "the difference between what a society produces and the costs of producing it" (Monopoly Capitalism, New York 1966, p. 9). Much depends here on how the costs are valued, and which costs are taken into account. Piero Sraffa also refers to a "physical surplus" with a similar meaning, calculated according to the relationship between prices of physical inputs and outputs.

In these theories, surplus product and surplus value are equated, while value and price are identical, but the distribution of the surplus tends to be separated theoretically from its production; whereas Marx insists that the distribution of wealth is governed by the social conditions in which it is produced, especially by property relations giving entitlement to products, incomes and assets (see also relations of production).

In Kapital Vol. 3, Marx insists strongly that:

...the specific economic form, in which unpaid surplus labour is pumped out of direct producers, determines the relationship of rulers and ruled, as it grows directly out of production itself and, in turn, reacts upon it as a determining element. Upon this, however, is founded the entire formation of the economic community which grows up out of the production relations themselves, thereby simultaneously its specific political form. It is always the direct relationship of the owners of the conditions of production to the direct producers – a relation always naturally corresponding to a definite stage of the methods of labour and thereby its social productivity – which reveals the innermost secret, the hidden basis of the entire social structure, and with it the political form of the relation of sovereignty and dependence, in short, the corresponding specific form of the state. This does not prevent the same economic basis – the same from the standpoint of its main conditions – due to innumerable different, empirical circumstances, natural environment, racial relations, external historical influence, etc. from showing infinite variations and gradations in appearance, which can be ascertained only by analysis of the empirically given circumstances.[18]

This is a substantive – if abstract – thesis about the basic social relations involved in giving and getting, taking and receiving in human society, and their consequences for the way work and wealth is shared out. It suggests a starting point for an inquiry into the problem of social order and social change. But obviously it is only a starting point, not the whole story, which would include all the "variations and gradations".

Morality and power

[edit]This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A textbook-type example of an alternative interpretation to Marx's is provided by Lester Thurow. He argues:[19] "In a capitalistic society, profits – and losses – hold center stage." But what, he asks, explains profits?

There are five reasons for profit, according to Thurow:

- Capitalists are willing to delay their own personal gratification, and profit is their reward.

- Some profits are a return to those who take risks.

- Some profits are a return to organizational ability, enterprise, and entrepreneurial energy

- Some profits are economic rents – a firm that has a monopoly in producing some product or service can set a price higher than would be set in a competitive market and, thus, earn higher than normal returns.

- Some profits are due to market imperfections – they arise when goods are traded above their competitive equilibrium price.

The problem here is that Thurow doesn't really provide an objective explanation of profits so much as a moral justification for profits, i.e. as a legitimate entitlement or claim, in return for the supply of capital.

He adds that "Attempts have been made to organize productive societies without the profit motive (...) [but] since the industrial revolution... there have been essentially no successful economies that have not taken advantage of the profit motive." The problem here is again a moral judgement, dependent on what you mean by success. Some societies using the profit motive were ruined; profit is no guarantee of success, although you can say that it has powerfully stimulated economic growth.

Thurow goes on to note that "When it comes to actually measuring profits, some difficult accounting issues arise." Why? Because after deduction of costs from gross income, "It is hard to say exactly how much must be reinvested to maintain the size of the capital stock". Ultimately, Thurow implies, the tax department is the arbiter of the profit volume, because it determines depreciation allowances and other costs which capitalists may annually deduct in calculating taxable gross income.

This is obviously a theory very different from Marx's. In Thurow's theory, the aim of business is to maintain the capital stock. In Marx's theory, competition, desire and market fluctuations create the striving and pressure to increase the capital stock; the whole aim of capitalist production is capital accumulation, i.e. business growth maximising net income. Marx argues there is no evidence that the profit accruing to capitalist owners is quantitatively connected to the "productive contribution" of the capital they own. In practice, within the capitalist firm, no standard procedure exists for measuring such a "productive contribution" and for distributing the residual income accordingly.

In Thurow's theory, profit is mainly just "something that happens" when costs are deducted from sales, or else a justly deserved income. For Marx, increasing profits is, at least in the longer term, the "bottom line" of business behaviour: the quest for obtaining extra surplus-value, and the incomes obtained from it, are what guides capitalist development (in modern language, "creating maximum shareholder value").

That quest, Marx notes, always involves a power relationship between different social classes and nations, inasmuch as attempts are made to force other people to pay for costs as much as possible, while maximising one's own entitlement or claims to income from economic activity. The clash of economic interests that invariably results, implies that the battle for surplus value will always involve an irreducible moral dimension; the whole process rests on complex system of negotiations, dealing and bargaining in which reasons for claims to wealth are asserted, usually within a legal framework and sometimes through wars. Underneath it all, Marx argues, was an exploitative relationship.

That was the main reason why, Marx argues, the real sources of surplus-value were shrouded or obscured by ideology, and why Marx thought that political economy merited a critique. Quite simply, economics proved unable to theorise capitalism as a social system, at least not without moral biases intruding in the very definition of its conceptual distinctions. Hence, even the most simple economic concepts were often riddled with contradictions. But market trade could function fine, even if the theory of markets was false; all that was required was an agreed and legally enforceable accounting system. On this point, Marx probably would have agreed with Austrian School economics – no knowledge of "markets in general" is required to participate in markets.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Spago incorrectly claims that "surplus value" appears in The Source and Remedy of the National Difficulties (1821), by Charles Wentworth Dilke, claiming that "the quantity of the surplus value appropriated by the capitalist" appears in that text. This is a misreading of the Preface to Capital, Volume II by Engels, who quotes from this pamphlet but uses the phrase himself (not in quotes); the pamphlet uses "surplus labour".

- ^ David McLellan once claimed that Marx first used the term ‘surplus-value’ in his articles on ‘The Law against Thefts of Timber’ in 1842. David McLellan, Marx before Marxism, 2nd edn. (London: Macmillan, 1980), pp. 96 and 217.

- ^ Sowell, Thomas (1985). Marxism: Philosophy and Economics. William Morrow. p. 220. ISBN 978-0688029630.

Despite the massive intellectual feat that Marx's Capital represents, the Marxian contribution to economics can be readily summarized as virtually zero.

- ^ Marx, The Capital, Chapter 8

- ^ "...It was made clear that the wage worker has permission to work for his own subsistence—that is, to live, only insofar as he works for a certain time gratis for the capitalist (and hence also for the latter's co-consumers of surplus value)..." Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Programme. Sec.II

- ^ W. Tcherkesoff (1902). Pages of Socialist History: Teachings and Acts of Social Democracy. C.B. Cooper. p. 19.

- ^ Menger, Anton (1899) [1886]. Das Recht auf den vollen Arbeitsertrag in geschichtlicher Darstellung [The Right to the Whole Produce of Labour] (in German).

- ^ "Juristen-Sozialismus" [Juridical Socialism]. Die Neue Zeit (in German). 1887.

- ^ Spargo, John (1906). Socialism: A Summary and Interpretation of Socialist Principles. pp. 203–206.

- ^ Vygodsky, Vitaly. "Surplus Value".

- ^ Marxists Internet Archive

- ^ Karatani, Kōjin. Transcritique: on Kant and Marx. pp. 248–251.

- ^ "Economic Manuscripts: Capital Vol. I - Chapter Twelve".

- ^ Marxists Internet Archive

- ^ Karl Marx and Frederick The Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 34 (New York: International Publishers, 1994) p. 63.

- ^ Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 34, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 34, p. 77.

- ^ "Measuring the Wealth of Nations - Cambridge University Press".

- ^ Karl Marx, Economic Manuscripts: Capital, Vol.3, Chapter 47.

- ^ Thurow, Lester C. (2008). "Profits". Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Liberty Fund.

References

[edit]- Theories of Surplus-Value (1863)

- Value, Price and Profit (1865)

- Capital, Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Supplement B of Volume 3

- Anwar Shaikh and Ahmet Tonak, Measuring the Wealth of Nations

- Anwar Shaikh papers [1]

- G. A. Cohen (1988), History, Labour and Freedom: Themes from Marx, Oxford University Press

- Shane Mage, The Law of the Falling Tendency of the Rate of Profit; Its Place in the Marxian Theoretical System and Relevance to the US Economy. Phd Thesis, Columbia University, 1963.

- Tatyana Volkova and Felix Volkov, What Is Surplus Value? (Moscow: Progress Publishers), 1987.

- Fred Moseley papers

- Gerard Dumenil and Dominique Levy papers

- Steve Keen, Debunking Economics; The Naked Emperor of the Social Sciences. London: Zed Press, 2004.Economics: Debunking Economics Overview

- Emmanuel Farjoun and Moshe Machover, Laws of Chaos; A Probabilistic Approach to Political Economy, London: Verso, 1983.

- Peter Flaschel, Nils Fröhlich & Roberto Veneziani, "The sources of aggregate profitability: Marx's theory of surplus value revisited". European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies, Vol. 10, Issue 3, 2013, pp. 299-312.[2]

- Ian Wright, iwright – Probabilistic Political Economy "Laws of Chaos" in the 21st Century.

- Ernest Mandel, Marxist Economic Theory, Vol. 1 and Late Capitalism.

- Harry W. Pearson, "The economy has no surplus" in "Trade and market in the early empires. Economies in history and theory", edited by Karl Polanyi, Conrad M. Arensberg and Harry W. Pearson (New York/London: The Free Press: Collier-Macmillan, 1957).

- Paul A. Baran, The Political Economy of Growth.

- Piero Sraffa, Production of Commodities by means of commodities.

- Michał Kalecki, "The Determinants of Profits", in Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy 1933–1970.

- John B. Davis (ed), The economic surplus in advanced economies. Aldershot, Hants, England/Brookfield, Vt.: Elgar, 1992.

- Anders Danielson, The economic surplus : theory, measurement, applications. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1994.

- Helen Boss, Theories of surplus and transfer : parasites and producers in economic thought. Boston: Hyman, 1990.

External links

[edit]Surplus value

View on GrokipediaSurplus value is a foundational concept in Karl Marx's critique of capitalism, defined as the excess value produced by workers' labor beyond the cost of their labor-power, which capitalists appropriate as profit.[1] In Capital, Volume I, Marx explains that labor-power, purchased at its value equivalent to the worker's subsistence needs, possesses the capacity to generate new value during the production process exceeding that cost; for instance, if a worker's daily wage covers six hours of necessary labor to reproduce their labor-power, the additional six hours of extended labor create surplus value unpaid by the capitalist.[1] This mechanism, Marx argued, underlies the exploitation inherent in wage labor, fueling capital accumulation while sowing seeds of class conflict, as the rate of surplus value—calculated as surplus value divided by variable capital (wages)—measures the degree of exploitation.[1] Marx distinguished absolute surplus value, obtained by prolonging the workday, from relative surplus value, achieved by increasing productivity to shorten necessary labor time.[1] The theory rests on the labor theory of value, positing that commodity values derive solely from socially necessary labor time, a premise enabling surplus value as the source of all profit, rent, and interest.[2] However, this framework has encountered persistent empirical and theoretical challenges; mainstream economics, drawing on marginalist revolutions, attributes profits to factors like entrepreneurial risk, capital scarcity, and subjective utility rather than unpaid labor, with market prices often diverging from labor inputs in ways unpredicted by the model.[3] Empirical attempts to quantify surplus value rates across economies yield varying results but fail to demonstrate causal primacy over alternative explanations, such as those emphasizing technological innovation and consumer demand.[4][5] Critics, including Austrian economists, contend the theory overlooks the time preference and opportunity costs of capital, rendering surplus value an ideological construct rather than a verifiable economic reality.[6] Despite these refutations, Marxist scholars continue to refine and apply the concept in analyses of inequality and crises, though its influence wanes outside heterodox circles amid academia's noted ideological skews favoring interpretive over falsifiable frameworks.[7]

Core Concepts and Definition

Formal Definition in Marxian Economics

In Capital, Volume I, Karl Marx defines surplus value as the increment of value produced by the application of labor power beyond the portion required to reproduce that labor power itself, with the capitalist appropriating this unpaid portion as the source of profit.[1] The value newly created in production equals the sum of necessary labor—the labor time required to produce commodities equivalent in value to the worker's wages (denoted as v, the variable capital advanced)—and surplus labor, the excess labor time yielding surplus value (denoted as s).[8] Thus, the total value added by labor is expressed as v + s, where surplus value s represents the difference between the total value produced (v') and the reproduced value of labor power (v), or formally s = v' - v.[8][9] This formulation rests on the labor theory of value, positing that commodities exchange according to the socially necessary labor time embodied in them, and that labor power, as a commodity purchased by the capitalist at its reproduction cost (subsistence wages), generates more value during the working day than it costs to sustain.[1] Marx illustrates this through the working day divided into necessary labor time (e.g., 6 hours producing value equal to daily wages) and surplus labor time (e.g., an additional 3 hours producing unpaid value), assuming a 9-hour day; the ratio s/v yields the rate of surplus value, such as 50% in this case.[8] The mass of surplus value then equals the variable capital advanced multiplied by this rate (s = v × (s/v)), emphasizing exploitation not as moral failing but as an inherent structural feature of capitalist production where workers sell their capacity to work but do not receive the full value they create.[9] Marx distinguishes this from vulgar economic views of profit as arising from exchange or capital's "productivity," insisting surplus value originates solely in production from the difference between labor expended and labor compensated, verifiable through empirical analysis of wages versus output value in specific industries, such as English textile mills in the 1860s where data showed workers producing 100-200% more value than their wage costs.[8] This definition underpins Marx's critique of capitalism as a system perpetuating class antagonism via the systematic extraction of unpaid labor.Foundations in Labor Theory of Value

, asserts that the exchange value of commodities derives from the socially necessary labor time required for their production under prevailing technological and social conditions. This theory traces its roots to classical economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, but Marx refines it to emphasize abstract human labor as the substance of value, independent of specific use-values. In this framework, value creation occurs solely through labor, not from capital or land, as machines and raw materials merely transfer pre-existing value without generating new value themselves.[1] Surplus value emerges as a direct consequence of this value theory within capitalist production relations. Workers, compelled to sell their labor power as a commodity, receive wages equivalent to the value needed to reproduce that labor power—typically the cost of subsistence goods embodying the labor time for their production, estimated in Marx's era at around 6 hours per 12-hour workday in English factories as of the 1860s. Yet, under the capitalist's direction, the worker performs labor for the full workday, say 12 hours, creating value proportional to that entire duration.[10] The difference between the value produced and the value paid in wages constitutes surplus value, realized when the commodity is sold.[11] This mechanism hinges on the unique property of labor power: its capacity to yield more value through exertion than the value required for its own maintenance, enabling capitalists to appropriate unpaid labor without violating formal equality in exchange.[1] Marx illustrates this with the formula for the rate of surplus value, s/v, where s is surplus value and v is variable capital (wages); for instance, if necessary labor is 6 hours and surplus labor 6 hours, the rate is 100%.[8] Empirical observations from 19th-century British factory reports, such as those compiled in the 1860s Blue Books, supported Marx's claims of extended workdays generating such surpluses, though critics like Eugen Böhm-Bawerk later contested the LTV's empirical validity by highlighting marginal utility's role in pricing.[12]Historical Development

Pre-Marxist Precursors

Classical political economists in the 17th and 18th centuries developed early notions of surplus production that anticipated key elements of surplus value, particularly through the labor theory of value and the decomposition of commodity prices into wages, profits, and rents. These thinkers identified profits as arising from labor's output exceeding the costs of worker subsistence, though they framed this as a natural distribution rather than systematic appropriation.[13][14] Adam Smith, in his 1776 An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, posited that in primitive societies, exchange value equates directly to embodied labor time, but under division of labor and capital accumulation, value resolves into three shares: wages (for labor's maintenance), profits (for the capitalist's abstinence from consumption), and rent (for land). Smith argued that profits emerge because productive labor generates a surplus product beyond what is required to reproduce the laborer's necessities, with the capitalist advancing wages from stock to claim this excess as incentive for investment. However, Smith inconsistently attributed profit's source to capital itself in some passages, blurring the labor origin.[15][16] David Ricardo refined Smith's framework in his 1817 On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, asserting that commodity value derives from labor quantities under competitive conditions, with profits constituting the residual share after subsistence wages and differential rents are deducted from total output. Ricardo maintained that wages gravitate toward a physical minimum determined by worker reproduction costs (influenced by population dynamics as per Malthus), leaving any additional produce as profit to motivate capital deployment and technological advance. Unlike later formulations, Ricardo viewed this surplus allocation as equilibrating market forces rather than inherent inequity, and he grappled with how varying capital-labor ratios affect profit rates without resolving value-profit transformations.[17]Marx's Formulation and Evolution

Marx initially sketched the concept of surplus value in the Grundrisse der Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie (1857–1858), positing it as the excess value generated by capital through the exploitation of labor within the circuit of production and circulation, where surplus value equals the difference between the total value produced and the capital advanced, reinvested to expand accumulation.[18] This early formulation emphasized capital's self-valorization, with surplus value arising from the discrepancy between labor's productive capacity and the value of labor power, though still intertwined with broader notes on money and commodities.[19] Between 1861 and 1863, Marx refined the theory in Theories of Surplus-Value, a manuscript critiquing classical economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, who conflated surplus value with profit or rent without isolating its origin in unpaid labor.[2] Here, he clarified that surplus value emerges specifically from the extension of the working day beyond necessary labor time or increases in productivity reducing that time, distinguishing it from mere profit rates influenced by circulation; for instance, he argued that wages below value could temporarily boost surplus but not alter its fundamental source in surplus labor.[20] This work marked an evolution toward a more rigorous separation of surplus value production from its distribution, addressing Ricardo's errors in equating surplus with average profit across capitals of differing organic compositions.[2] The mature formulation appeared in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I (1867), particularly Chapters 7–9 and 16, where Marx defined surplus value (Mehrwert) as the value created by workers' labor power in excess of its own reproduction cost, realized when capitalists purchase labor power as a commodity at its value (equivalent to subsistence wages) but extract more value through the full working day.[21] Quantitatively, if variable capital v represents wages and surplus value s the unpaid portion, the total value added is v + s, with the rate of surplus value s/v measuring exploitation intensity; this built on prior drafts by integrating absolute surplus value (via extended hours) and relative surplus value (via productivity gains lowering necessary labor).[22] Subsequent volumes of Capital (published posthumously in 1885 and 1894) evolved the concept further by transforming surplus value into average profit via competition, resolving tensions between value production and price formation without altering its labor-based origin.[23]Mechanisms of Generation

Production Process

In capitalist production, the process begins with the capitalist purchasing labor-power as a commodity, alongside means of production, to initiate the labor process. Labor-power, unique among commodities, possesses the capacity to create new value during its consumption in production that exceeds its own exchange value, which is determined by the socially necessary labor time required to produce the means of subsistence for the worker and their family. The worker, compelled by the need to sell this labor-power to survive, enters the workplace where they combine it with instruments of labor and raw materials, transferring the preexisting value of the means of production (constant capital) to the output while adding fresh value through the expenditure of living labor. This added value, measured in abstract labor time under the labor theory of value, forms the basis for surplus value extraction.[1][8] The generation of surplus value hinges on the extension of the labor process beyond the point of reproducing the value of labor-power. Marx divides the working day into necessary labor time—during which the worker produces value equivalent to their wages, covering the reproduction costs of labor-power—and surplus labor time, in which additional value is created without equivalent compensation, appropriated by the capitalist as surplus value. For instance, if the value of labor-power requires four hours of labor to reproduce but the working day spans ten hours, the remaining six hours yield surplus value, assuming constant productivity. This mechanism presupposes the capitalist's control over the production process, enforcing discipline and intensity to maximize the surplus portion.[24][8] Empirical manifestations of this process appear in historical data on working hours and wage shares; for example, in mid-19th-century Britain, factory acts limited the working day to 10 hours from longer durations, yet wages often remained tied to subsistence levels, implying a persistent surplus labor component as documented in parliamentary reports cited by Marx. The production process thus transforms the circulation of commodities—M-C-M' (money-commodity-more money)—into value expansion solely through labor's productive power, not through exchange equivalents, distinguishing it from merchant profit. Critiques from marginalist economics, such as those emphasizing subjective utility over labor time, contest this by arguing value derives from demand, but Marxian analysis counters that such views abstract from the concrete labor dynamics observed in industrial production.[25][26]Absolute versus Relative Surplus Value

Absolute surplus-value arises from the extension of the working day beyond the portion required to reproduce the worker's labor power, thereby increasing the unpaid labor extracted without altering the underlying value of commodities or labor productivity.[24] In this method, capitalists prolong absolute working hours—such as from 8 to 12 hours daily—while the necessary labor time to produce subsistence goods remains constant, directly amplifying the surplus labor segment appropriated as profit.[27] This approach dominated early capitalist accumulation, exemplified in 19th-century British factories where legislation like the Factory Acts of 1833 and 1847 capped daily hours at 9-12 for children and adults, respectively, after struggles against unchecked extensions that once exceeded 16 hours.[24] Relative surplus-value, by contrast, emerges from reductions in the necessary labor time through technological advancements, intensified division of labor, or cooperation that lower the socially average production cost of wage goods, thereby expanding the surplus labor portion within a fixed working day.[24] Marx describes this as transforming the technical processes of production, such as machinery implementation that halves the labor needed for commodity reproduction, shifting value creation dynamics without relying on mere temporal extension.[22] For instance, the introduction of steam-powered looms in textile mills during the Industrial Revolution decreased yarn production time, compressing necessary labor and elevating relative surplus extraction across competing firms under the law of value equalization.[27] The distinction underscores a progression in capitalist development: absolute methods face physiological and legal limits on working hours, prompting a shift to relative strategies that internalize exploitation via productivity gains, though both ultimately rest on the extension of unpaid labor relative to paid.[24] Relative surplus-value production presupposes prior absolute extraction, as shorter necessary labor times compel capitalists to maintain or extend total hours to realize gains, intertwining the two in a dialectical process where technological "progress" serves accumulation imperatives rather than worker welfare.[28] Empirical manifestations include post-1848 European industrialization, where relative methods supplanted absolute dominance amid rising proletarian resistance and state interventions, yet perpetuated value extraction through capital-intensive reorganization.[29]Measurement and Rates

Calculating the Rate of Surplus Value

The rate of surplus value in Marxian economics is calculated as the ratio of surplus value (s) to variable capital (v), denoted mathematically as or .[8] Variable capital (v) consists of the monetary wages advanced to workers, equivalent to the value of labor power required for its reproduction, while surplus value (s) represents the additional value produced by labor beyond v during the workday.[8] This yields a measure of the degree of exploitation, independent of constant capital (c, such as machinery and raw materials), as c transfers its value without creating new value.[30] Derivation proceeds from the labor theory of value, where the total value of commodities equals the socially necessary labor time embodied in them.[8] The workday divides into necessary labor time (reproducing v) and surplus labor time (generating s), so equals surplus labor time divided by necessary labor time; for instance, if necessary labor is 6 hours and surplus labor is 6 hours, the rate is 100%.[8] Marx equates this to monetary forms: if v = 20 pounds and s = 20 pounds (from sales exceeding costs), the rate is 100%.[30] Alternative formulae, such as s / (s + v), express the share of surplus in total variable capital value but understate the rate by conflating paid and unpaid labor, as critiqued in Marx's analysis of factory inspector reports showing apparent rates of 0–322.5% versus true s/v exceeding 100%.[31] Practical computation requires isolating value created by living labor from total output value, subtracting v (wages) to obtain s.[8] In aggregate terms, this involves estimating socially necessary labor coefficients via input-output data, adjusting for productivity to derive s/v; for example, UK data from 1850s factory reports yielded rates around 100–150% after correcting for overtime and piece-wages.[31] Empirical applications in quantitative Marxism use national accounts to approximate s as value added minus employee compensation, though deviations arise from price-value transformations and unproductive labor exclusions.[32] Such methods assume uniform exploitation rates across sectors post-equalization, with s/v rising via relative surplus value (e.g., through machinery intensifying labor).[8]Equalization and Transformation Issues

In Marxian economics, the equalization of profit rates across industries arises from capitalist competition, which redistributes total surplus value such that capitals of equal size yield equal profits regardless of their organic composition of capital (the ratio of constant capital c to variable capital v). Industries with higher organic compositions produce less surplus value per unit of total capital (s/(c+v)) due to a smaller proportion of living labor, yet competition drives capital mobility and price adjustments, compelling prices to deviate from labor values toward prices of production (c + v + average profit). This process ensures that the aggregate mass of profit equals the aggregate mass of surplus value, as the total social capital's profit rate averages out, with surplus value from labor-intensive sectors subsidizing capital-intensive ones.[23][33] The transformation problem refers to the methodological challenge of deriving these prices of production from underlying values, where value is socially necessary labor time embodied in commodities. Marx outlined this in Capital Volume III, positing that while individual commodity prices fluctuate around values due to supply-demand dynamics, the long-term tendency under competition transforms values into prices of production by adding an average rate of profit to the cost price (c + v). However, critics, beginning with Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk in 1896, argued that Marx's numerical illustrations inconsistently transformed only output prices while assuming input values remained unchanged, leading to discrepancies where the total profit might not equal total surplus value or where the average profit rate is calculated from untransformed inputs.[23][34] Defenders of Marx, such as those employing simultaneous valuation methods, contend that a consistent transformation requires solving input-output prices iteratively, preserving aggregate equalities: total prices equal total values, and total profits equal total surplus value (Π = Σs), as deviations cancel out across the economy. Empirical simulations using input-output tables, such as those from the U.S. economy in the 1970s, have shown that deviations between values and prices are empirically small (often under 10-20% for most sectors), supporting the approximation without invalidating the surplus value origin of profit. Yet, methodological critiques persist, with some Marxian economists like Anwar Shaikh arguing for a "new solution" via actual empirical price data, while others highlight that sequential transformation (inputs at values, outputs at prices) aligns with Marx's intent but risks circularity in rate calculations.[35][36][37] These issues underscore tensions in linking micro-level value production to macro-level profit distribution, with non-Marxian critiques (e.g., from neoclassical economics) dismissing the labor theory of value altogether as incompatible with marginal utility, though such objections often overlook Marx's focus on abstract social averages rather than marginal exchanges. Within Marxian theory, unresolved debates include whether the transformation implies a dualistic value-price system or a unified magnitude where profit equalization reveals surplus value's relational dynamics across capitals, potentially affecting predictions of the falling tendency of the profit rate.[22][38]Theoretical Extensions and Interpretations

Realization versus Production

In Marxist theory, surplus value originates solely in the sphere of production, arising from the difference between the new value created by workers' labor and the value of their labor power, which is compensated only for the socially necessary labor time required to reproduce that power. This process unfolds as unpaid labor time extends beyond the paid portion, embedding surplus value within the commodities produced, independent of subsequent market exchanges.[1] Circulation, or the exchange of commodities, generates no surplus value, serving merely to metamorphose its form from commodities to money; any apparent value expansion through unequal exchange—such as buying below value and selling above—results only in redistribution among capitalists, with no net increase for the class as a whole.[25] Marx explicitly states that "circulation, or the exchange of commodities, begets no value," as the total value exchanged remains constant regardless of individual gains or losses.[25] Realization of surplus value occurs during circulation when these value-laden commodities are sold at prices approximating their values, converting the embedded surplus from commodity-capital (C') into money-capital (M'), thereby enabling its withdrawal from circulation in excess of the originally advanced sum.[39] For aggregate realization, the capitalist class must extract more money than injected, facilitated by existing hoards, new money creation (e.g., via gold mining), or prior expenditures that replenish circulation; without this, produced surplus remains trapped unrealized.[39] In the circuit of industrial capital (M-C...P...C'-M'), production (P) creates the surplus within C', but realization hinges on solvent demand derived from workers' wages and capitalists' revenue from past cycles, rendering it vulnerable to imbalances where output exceeds purchasing power.[39] Disruptions, such as overproduction relative to effective demand, prevent full realization, converting potential surplus into unsold inventories and precipitating crises that contract production despite ongoing value creation capacity.[40] Extensions in Capital Volume II's reproduction schemas demonstrate how surplus value realization supports expanded accumulation by partitioning it between reinvestment in constant capital (Department I: means of production) and variable capital plus consumption (Department II), ensuring balanced growth; imbalances here amplify realization barriers.[39] Later Marxian analyses, applying input-output tables to national data, quantify production-realization gaps, attributing them to deviations in prices of production from values and inter-industry transfers, where surplus generated in one sector realizes as profit elsewhere under a uniform exploitation rate.[5] Such frameworks highlight realization not as mere formalism but as a structural limit conditioning the transformation of surplus value into profit and accumulation.[41]Circuits of Capital and Accumulation

In Marx's analysis, the circuit of capital traces the functional forms assumed by capital in its drive to self-expand through the production and realization of surplus value. The basic formula for the circuit of money-capital is M–C (...P...)–C′–M′, where an initial advance of money (M) purchases commodities (C), including means of production and labor power; these enter the production process (P) to yield commodities (C′) whose value exceeds the input costs by the amount of surplus value; and C′ is then sold to recover money capital plus surplus value (M′ > M).[42] This circuit presupposes the extraction of surplus value during P via unpaid labor time, with realization occurring only upon sale in circulation.[42] Marx identifies three interconnected circuits corresponding to capital's forms: money-capital (M–C...P...C′–M′), productive-capital (P...C′–M′–C...P), and commodity-capital (C′–M′–C...P...C′), each highlighting potential disruptions but collectively ensuring the rotation necessary for ongoing valorization.[42] Accumulation arises when a portion of realized surplus value is withheld from unproductive consumption and reconverted into capital, augmenting both constant capital (means of production) and variable capital (labor power) for subsequent circuits on an enlarged scale.[43] This process, detailed in schemes of reproduction, contrasts simple reproduction—where all surplus value is expended as revenue by capitalists on personal consumption, sustaining but not expanding production—with expanded reproduction, in which accumulated surplus value fuels growth, progressively increasing the mass of capital and surplus value generated. In the latter, surplus value divides into a capitalized fraction (becoming additional M for new circuits) and a revenue fraction, with reinvestment requiring proportional expansion across departments of production: Department I (means of production) and Department II (articles of consumption).[44] For equilibrium in expanded reproduction, Marx posits that accumulated surplus from Department I must supply additional constant capital for both departments, while Department II's output meets increased worker consumption (variable capital) plus capitalist revenue, preventing overproduction crises in circulation.[45] These schemes assume a given organic composition of capital and rate of surplus value, illustrating how uninterrupted circuits depend on balanced inter-departmental exchanges, though Marx notes real-world deviations arise from uneven accumulation rates.[44] Accumulation thus propels capital's circuits toward greater magnitude, concentrating wealth while intensifying contradictions in realizing surplus value amid rising organic composition.[43]Critiques from Alternative Economic Theories

Neoclassical and Marginalist Objections

Neoclassical and marginalist economists reject the Marxist concept of surplus value by denying the foundational labor theory of value (LTV), which posits that value derives solely from abstract labor time. Instead, marginalism, originating with Carl Menger, William Stanley Jevons, and Léon Walras in the 1870s, holds that value emerges from subjective marginal utility—the incremental satisfaction derived from additional units of goods or services in consumption. This subjective theory eliminates any objective "surplus" as unpaid labor, as exchange values reflect individual preferences and opportunity costs rather than embedded labor quantities. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, building on this in his 1889 Capital and Interest, critiqued Marx's LTV for failing to explain interest and profit as arising from time preference—the premium for present over future goods—rather than exploitation, arguing that capital's productivity stems from "roundabout" production processes that amplify output beyond immediate labor input. A core objection lies in the neoclassical distribution theory, where wages equal the marginal revenue product of labor (MRPL)—the additional revenue generated by the last unit of labor employed—ensuring workers receive the full value of their contribution in competitive markets. Profits, then, represent the marginal product of capital and entrepreneurship, compensating for risk, innovation, and deferred consumption, not expropriation. John Bates Clark formalized this in his 1899 The Distribution of Wealth, asserting that ethical justice in capitalism occurs when each factor, including labor, claims precisely its marginal product, leaving no residual surplus value to be theorized as theft. Böhm-Bawerk extended this critique to Marx's surplus value by highlighting inconsistencies in Capital Volume III, where the "transformation problem"—converting labor values into prices of production with equalized profit rates—undermines the claim that surplus value aggregates into total profits, as deviations between values and prices prevent consistent measurement of exploitation across sectors. Marginalists further argue that labor contracts are voluntary exchanges in a market where workers sell their services at equilibrium wages determined by supply, demand, and productivity, negating coercion inherent in surplus value extraction. Empirical observations, such as the historical alignment of real wage growth with labor productivity increases—for instance, U.S. nonfarm business sector productivity rising 2.1% annually from 1947 to 2023 alongside comparable wage gains—support this, contradicting Marx's prediction of persistent relative immiseration through surplus appropriation. Paul Samuelson, in neoclassical tradition, summarized this by noting that Marxian "exploitation" dissolves under marginal productivity analysis, as competitive equilibrium allocates outputs proportionally to inputs' elasticities, with no systemic underpayment. These objections prioritize causal mechanisms like utility maximization and marginal analysis over class-based value derivation, viewing surplus value as a theoretical artifact lacking empirical or logical foundation in modern economics.Austrian School Perspectives

Austrian School economists fundamentally reject the Marxist concept of surplus value, viewing it as predicated on the erroneous labor theory of value, which posits that value derives solely from socially necessary labor time. Instead, they adhere to the subjective theory of value, originated by Carl Menger in 1871, wherein value emerges from individual valuations based on marginal utility and ordinal preferences rather than objective labor inputs. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, in his 1896 critique Karl Marx and the Close of His System, argued that Marx's framework fails to account for the productivity of capital goods and time preference, leading to an inconsistent explanation of profits as exploitation; he demonstrated through numerical examples that exchange ratios under capitalism reflect time-structured production processes, not coerced surplus extraction from labor. Böhm-Bawerk emphasized that workers receive wages equivalent to the discounted present value of their future marginal contributions, negating any systematic "surplus" appropriation by capitalists.[46] Ludwig von Mises further dismantled the exploitation theory underlying surplus value, asserting in Human Action (1949) that profits arise not from underpayment but from entrepreneurial foresight in coordinating scarce resources under uncertainty, with wages determined by the marginal productivity of labor in a voluntary market. Mises contended that Marx's assumption of labor as the sole value creator ignores the role of capital accumulation and interest as compensation for time preference—the preference for present over future goods—rendering surplus value a fictitious category devoid of empirical or logical foundation. He highlighted that in a free market, any apparent "exploitation" dissipates through competition, as workers can always seek alternative employments reflecting their full productivity, and historical data on rising real wages under capitalism contradicts predictions of immiseration.[47] Murray Rothbard echoed these views in Man, Economy, and State (1962), critiquing surplus value as a misattribution of profits to theft rather than to the capitalist-entrepreneur's risk-bearing and innovation, which enable production beyond mere labor application. Rothbard argued that under the labor theory, all income except wages appears as unearned, but subjective valuation and catallactic exchange ensure that profits represent consumer-validated efficiencies, not zero-sum extraction; he cited the impossibility of calculating surplus value without arbitrary assumptions about labor equivalence, underscoring its methodological flaws. Austrian critiques collectively maintain that surplus value obfuscates genuine economic phenomena like interest and profit, which stem from human action in time and uncertainty, rather than class antagonism.[48]Methodological and Empirical Challenges