Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Der Ring des Nibelungen

View on Wikipedia

| Der Ring des Nibelungen | |

|---|---|

| Music dramas by Richard Wagner | |

| |

| Translation | The Ring of the Nibelung |

| Librettist | Richard Wagner |

| Language | German |

| Premiere |

|

Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the Nibelungenlied. The composer termed the cycle a "Bühnenfestspiel" (stage festival play), structured in three days preceded by a Vorabend ("preliminary evening"). It is often referred to as the Ring cycle, Wagner's Ring, or simply The Ring.

Wagner wrote the libretto and music over the course of about twenty-six years, from 1848 to 1874. The four parts that constitute the Ring cycle are, in sequence:

- Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold)

- Die Walküre (The Valkyrie)

- Siegfried

- Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods)

Individual works of the sequence are often performed separately,[1] and indeed the operas contain dialogues that mention events in the previous operas, so that a viewer could watch any of them without having watched the previous parts and still understand the plot. However, Wagner intended them to be performed in series. The first performance as a cycle opened the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876, beginning with Das Rheingold on 13 August and ending with Götterdämmerung on 17 August. Opera stage director Anthony Freud stated that Der Ring des Nibelungen "marks the high-water mark of our art form, the most massive challenge any opera company can undertake."[2]

Title

[edit]Wagner's title is most literally rendered in English as The Ring of the Nibelung. The Nibelung of the title is the dwarf Alberich, and the ring in question is the one he fashions from the Rhinegold. The title therefore denotes "Alberich's Ring".[3]

Content

[edit]The cycle is a work of extraordinary scale.[4] A full performance of the cycle takes place over four nights at the opera, with a total playing time of about 15 hours, depending on the conductor's pacing. The first and shortest work, Das Rheingold, has no interval and is one continuous piece of music typically lasting around two and a half hours, while the final and longest, Götterdämmerung, takes up to five hours, excluding intervals. The cycle is modelled after ancient Greek dramas that were presented as three tragedies and one satyr play. The Ring proper begins with Die Walküre and ends with Götterdämmerung, with Rheingold as a prelude. Wagner called Das Rheingold a Vorabend or "Preliminary Evening", and Die Walküre, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung were subtitled First Day, Second Day and Third Day, respectively, of the trilogy proper.

The scale and scope of the story is epic. It follows the struggles of gods, heroes, and several mythical creatures over the eponymous magic ring that grants domination over the entire world. The drama and intrigue continue through three generations of protagonists, until the final cataclysm at the end of Götterdämmerung.

The music of the cycle is thick and richly textured, and grows in complexity as the cycle proceeds. Wagner wrote for an orchestra of gargantuan proportions, including a greatly enlarged brass section with instruments such as the Wagner tuba, bass trumpet and contrabass trombone. Remarkably, he uses a chorus only relatively briefly, in acts 2 and 3 of Götterdämmerung, and then mostly of men with just a few women. He eventually had a purpose-built theatre constructed, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, in which to perform this work. The theatre has a special stage that blends the huge orchestra with the singers' voices, allowing them to sing at a natural volume. The result was that the singers did not have to strain themselves vocally during the long performances.

List of characters

[edit]| Gods | Mortals | Valkyries | Rhinemaidens, Giants & Nibelungs | Other characters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Neidings

|

|

Rhinemaidens

Giants

Nibelungs |

|

List of characters by appearance

[edit]| Character | Das Rheingold[5] | Die Walküre[6] | Siegfried[7] | Götterdämmerung[8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wotan | Yes | Yes | Yes[a] | No |

| Fricka | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Loge | Yes | No | No | No |

| Freia | Yes | No | No | No |

| Donner | Yes | No | No | No |

| Froh | Yes | No | No | No |

| Erda | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Woglinde | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Wellgunde | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Flosshilde | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Fasolt | Yes | No | No | No |

| Fafner | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Alberich | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Mime | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Siegmund | No | Yes | No | No |

| Sieglinde | No | Yes | No | No |

| Hunding | No | Yes | No | No |

| Brünnhilde | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gerhilde | No | Yes | No | No |

| Ortlinde | No | Yes | No | No |

| Waltraute | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Schwertleite | No | Yes | No | No |

| Helmwige | No | Yes | No | No |

| Siegrune | No | Yes | No | No |

| Grimgerde | No | Yes | No | No |

| Rossweisse | No | Yes | No | No |

| Siegfried | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| The Woodbird | No | No | Yes | No |

| The Norns | No | No | No | Yes |

| Gunther | No | No | No | Yes |

| Gutrune | No | No | No | Yes |

| Hagen | No | No | No | Yes |

| Vassals | No | No | No | Yes |

| Women | No | No | No | Yes |

Story

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

The plot revolves around a magic ring that grants the power to rule the world, forged by the Nibelung dwarf Alberich from gold he stole from the Rhine maidens in the river Rhine. With the assistance of the god Loge, Wotan – the chief of the gods – steals the ring from Alberich, but is forced to hand it over to the giants Fafner and Fasolt in payment for building the home of the gods, Valhalla, or they will take Freia, who provides the gods with the golden apples that keep them young. Wotan's schemes to regain the ring, spanning generations, drive much of the action in the story. His grandson, the mortal Siegfried, wins the ring by slaying Fafner (who slew Fasolt for the ring) – as Wotan intended – but is eventually betrayed and slain as a result of the intrigues of Alberich's son Hagen, who wants the ring for himself. Finally, the Valkyrie Brünnhilde – Siegfried's lover and Wotan's daughter who lost her immortality for defying her father in an attempt to save Siegfried's father Sigmund – returns the ring to the Rhine maidens as she commits suicide on Siegfried's funeral pyre. Hagen is drowned as he attempts to recover the ring. In the process, the gods and Valhalla are destroyed.

Wagner created the story of the Ring by fusing elements from many German and Scandinavian myths and folk-tales. The Old Norse Edda supplied much of the material for Das Rheingold, while Die Walküre was largely based on the Völsunga saga. Siegfried contains elements from the Eddur, the Völsunga saga and Thidrekssaga. The final Götterdämmerung draws from the 12th-century German poem, the Nibelungenlied, which appears to have been the original inspiration for the Ring.[9]

The Ring has been the subject of myriad interpretations. For example, George Bernard Shaw, in The Perfect Wagnerite, argues for a view of The Ring as an essentially socialist critique of industrial society and its abuses. Robert Donington in Wagner's Ring And Its Symbols interprets it in terms of Jungian psychology, as an account of the development of unconscious archetypes in the mind, leading towards individuation.

Concept

[edit]In his earlier operas (up to and including Lohengrin) Wagner's style had been based, rather than on the Italian style of opera, on the German style as developed by Carl Maria von Weber, with elements of the grand opera style of Giacomo Meyerbeer. However he came to be dissatisfied with such a format as a means of artistic expression. He expressed this clearly in his essay "A Communication to My Friends" (1851), in which he condemned the majority of modern artists, in painting and in music, as "feminine ... the world of art close fenced from Life, in which Art plays with herself.' Where however the impressions of Life produce an overwhelming 'poetic force', we find the 'masculine, the generative path of Art'.[10]

Wagner unfortunately found that his audiences were not willing to follow where he led them:

The public, by their enthusiastic reception of Rienzi and their cooler welcome of the Flying Dutchman, had plainly shown me what I must set before them if I sought to please. I completely undeceived their expectations; they left the theatre, after the first performance of Tannhäuser, [1845] in a confused and discontented mood. – The feeling of utter loneliness in which I now found myself, quite unmanned me... My Tannhäuser had appealed to a handful of intimate friends alone.[11]

Finally Wagner announces:

I shall never write an Opera more. As I have no wish to invent an arbitrary title for my works, I will call them Dramas ...

I propose to produce my myth in three complete dramas, preceded by a lengthy Prelude (Vorspiel). ...

At a specially-appointed Festival, I propose, some future time, to produce those three Dramas with their Prelude, in the course of three days and a fore-evening. The object of this production I shall consider thoroughly attained, if I and my artistic comrades, the actual performers, shall within these four evenings succeed in artistically conveying my purpose to the true Emotional (not the Critical) Understanding of spectators who shall have gathered together expressly to learn it.[12]

This is his first public announcement of the form of what would become the Ring cycle.

In accordance with the ideas expressed in his essays of the period 1849–51 (including the "Communication" but also Opera and Drama and "The Artwork of the Future"), the four parts of the Ring were originally conceived by Wagner to be free of the traditional operatic concepts of aria and operatic chorus. The Wagner scholar Curt von Westernhagen identified three important problems discussed in "Opera and Drama" which were particularly relevant to the Ring cycle: the problem of unifying verse stress with melody; the disjunctions caused by formal arias in dramatic structure and the way in which opera music could be organised on a different basis of organic growth and modulation; and the function of musical motifs in linking elements of the plot whose connections might otherwise be inexplicit. This became known as the leitmotif technique (see below), although Wagner himself did not use this word.[13]

However, Wagner relaxed some aspects of his self-imposed restrictions somewhat as the work progressed. As George Bernard Shaw sardonically (and slightly unfairly)[14] noted of the last opera Götterdämmerung:

And now, O Nibelungen Spectator, pluck up; for all allegories come to an end somewhere... The rest of what you are going to see is opera and nothing but opera. Before many bars have been played, Siegfried and the wakened Brynhild, newly become tenor and soprano, will sing a concerted cadenza; plunge on from that to a magnificent love duet...The work which follows, entitled Night Falls on the Gods [Shaw's translation of Götterdämmerung], is a thorough grand opera.[15]

Music

[edit]Leitmotifs

[edit]As a significant element in the Ring and his subsequent works, Wagner adopted the use of leitmotifs, which are recurring themes or harmonic progressions. They musically denote an action, object, emotion, character, or other subject mentioned in the text or presented onstage. Wagner referred to them in "Opera and Drama" as "guides-to-feeling", describing how they could be used to inform the listener of a musical or dramatic subtext to the action onstage in the same way as a Greek chorus did for the theatre of ancient Greece.

Instrumentation

[edit]Wagner made significant innovations in orchestration in this work. He wrote for a very large orchestra, using the whole range of instruments used singly or in combination to express the great range of emotion and events of the drama. Wagner even commissioned the production of new instruments, including the Wagner tuba, invented to fill a gap he found between the tone qualities of the horn and the trombone, as well as variations of existing instruments, such as the bass trumpet and a contrabass trombone with a double slide. He also developed the "Wagner bell", enabling the bassoon to reach the low A-natural, whereas normally B-flat is the instrument's lowest note. If such a bell is not to be used, then a contrabassoon should be employed.

All four parts have a very similar instrumentation. The core ensemble of instruments are one piccolo, three flutes (third doubling second piccolo), three oboes, cor anglais (doubling fourth oboe), three soprano clarinets, one bass clarinet, three bassoons; eight horns (fifth through eighth doubling Wagner tubas), three trumpets, one bass trumpet, three tenor trombones, one contrabass trombone (doubling bass trombone), one contrabass tuba; a percussion section with 4 timpani (requiring two players), triangle, cymbals, tam-tam; six harps and a string section consisting of 16 first and 16 second violins, 12 violas, 12 cellos and 8 double basses.

Das Rheingold requires one bass drum, one onstage harp and 18 onstage anvils. Die Walküre requires one snare drum, one D clarinet (played by the third clarinettist) and an on-stage steerhorn. Siegfried requires one onstage cor anglais and one onstage horn. Götterdämmerung requires a tenor drum, as well as five onstage horns and four onstage steerhorns, one of them to be blown by Hagen.[16]

Tonality

[edit]Much of the Ring, especially from Siegfried act 3 onwards, cannot be said to be in traditional, clearly defined keys for long stretches, but rather in 'key regions', each of which flows smoothly into the following. This fluidity avoided the musical equivalent of clearly defined musical paragraphs and assisted Wagner in building the work's huge structures. Tonal indeterminacy was heightened by the increased freedom with which he used dissonance and chromaticism. Chromatically altered chords are used very liberally in the Ring and this feature, which is also prominent in Tristan und Isolde, is often cited as a milestone on the way to Arnold Schoenberg's revolutionary break with the traditional concept of key and his dissolution of consonance as the basis of an organising principle in music.[citation needed]

Composition

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

In summer 1848 Wagner wrote The Nibelung Myth as Sketch for a Drama, combining the medieval sources previously mentioned into a single narrative, very similar to the plot of the eventual Ring cycle, but nevertheless with substantial differences. Later that year he began writing a libretto entitled Siegfrieds Tod ("Siegfried's Death"). He was possibly stimulated by a series of articles in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, inviting composers to write a 'national opera' based on the Nibelungenlied, a 12th-century High German poem which, since its rediscovery in 1755, had been hailed by the German Romantics as the "German national epic". Siegfrieds Tod dealt with the death of Siegfried, the central heroic figure of the Nibelungenlied. The idea had occurred to others – the correspondence of Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn in 1840/41 reveals that they were both outlining scenarios on the subject: Fanny wrote 'The hunt with Siegfried's death provides a splendid finale to the second act'.[17]

By 1850, Wagner had completed a musical sketch (which he abandoned) for Siegfrieds Tod.[citation needed] He now felt that he needed a preliminary opera, Der junge Siegfried ("The Young Siegfried", later renamed to "Siegfried"), to explain the events in Siegfrieds Tod and his verse draft of this was completed in May 1851.[citation needed] By October, he had made the momentous decision to embark on a cycle of four operas, to be played over four nights: Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Der Junge Siegfried and Siegfrieds Tod; the text for all four parts was completed in December 1852 and privately published in February 1853.[citation needed]

In November 1853, Wagner began the composition draft of Das Rheingold. Unlike the verses, which were written as it were in reverse order, the music would be composed in the same order as the narrative. Composition proceeded until 1857, when the final score up to the end of act 2 of Siegfried was completed. Wagner then laid the work aside for twelve years, during which he wrote Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

By 1869, Wagner was living at Tribschen on Lake Lucerne, sponsored by King Ludwig II of Bavaria. He returned to Siegfried and, remarkably, was able to pick up where he left off. In October, he completed the final work in the cycle. He chose the title Götterdämmerung instead of Siegfrieds Tod. In the completed work the gods are destroyed in accordance with the new pessimistic thrust of the cycle, not redeemed as in the more optimistic originally planned ending. Wagner also decided to show onstage the events of Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, which had hitherto only been presented as back-narration in the other two parts. These changes resulted in some discrepancies in the cycle, but these do not diminish the value of the work.

Performances

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

First productions

[edit]

On King Ludwig's insistence, and over Wagner's objections, "special previews" of Das Rheingold and Die Walküre were given at the National Theatre in Munich, before the rest of the Ring. Thus, Das Rheingold premiered on 22 September 1869 and Die Walküre on 26 June 1870. Wagner subsequently delayed announcing his completion of Siegfried to prevent this work also being premiered against his wishes.

Wagner had long desired to have a special festival opera house, designed by himself, for the performance of the Ring. In 1871, he decided on a location in the Bavarian town of Bayreuth. In 1872, he moved to Bayreuth and the foundation stone was laid. Wagner would spend the next two years attempting to raise capital for the construction, with scant success; King Ludwig finally rescued the project in 1874 by donating the needed funds. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus opened in 1876 with the first complete performance of the Ring, which took place from 13 to 17 August.

In 1882, London impresario Alfred Schulz-Curtius organized the first staging in the United Kingdom of the Ring cycle, conducted by Anton Seidl and directed by Angelo Neumann.[18]

The first production of the Ring in Italy was in Venice (the place where Wagner died), just two months after his 1883 death, at La Fenice.[19]

The first Australian Ring (and The Mastersingers of Nuremberg) was presented in an English-language production by the British travelling Quinlan Opera Company, in conjunction with J. C. Williamson's, in Melbourne and Sydney in 1913.[20]

Modern productions

[edit]

The Ring is a major undertaking for any opera company: staging four interlinked operas requires a huge commitment both artistically and financially; hence, in most opera houses, production of a new Ring cycle will happen over a number of years, with one or two operas in the cycle being added each year. The Bayreuth Festival, where the complete cycle is performed most years, is unusual in that a new cycle is almost always created within a single year.

Early productions of the Ring cycle stayed close to Wagner's original Bayreuth staging. Trends set at Bayreuth have continued to be influential. Following the closure of the Festspielhaus during the Second World War, the 1950s saw productions by Wagner's grandsons Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner (known as the "New Bayreuth" style), which emphasised the human aspects of the drama in a more abstract setting.[21]

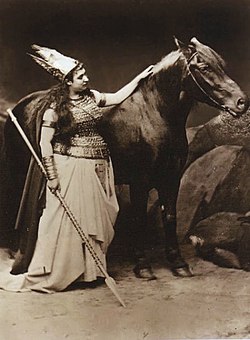

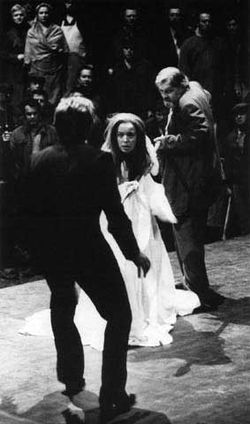

Perhaps the most famous modern production was the centennial production of 1976, the Jahrhundertring, directed by Patrice Chéreau and conducted by Pierre Boulez.[22] Set in the Industrial Revolution, it replaced the depths of the Rhine with a hydroelectric power dam and featured grimy sets populated by men and gods in 19th and 20th century business suits. This drew heavily on the reading of the Ring as a revolutionary drama and critique of the modern world, famously expounded by George Bernard Shaw in The Perfect Wagnerite. Early performances were booed but the audience of 1980 gave it a 45-minute ovation in its final year.[23][24]

Seattle Opera has created three different productions of the tetralogy: Ring 1, 1975 to 1984: Originally directed by George London, with designs by John Naccarato following the famous illustrations by Arthur Rackham. It was performed twice each summer, once in German, once in Andrew Porter's English adaptation. Henry Holt conducted all performances. Ring 2, 1985–1995: Directed by Francois Rochaix, with sets and costumes designed by Robert Israel, lighting by Joan Sullivan and supertitles (the first ever created for the Ring) by Sonya Friedman. The production set the action in a world of nineteenth-century theatricality; it was initially controversial in 1985, it sold out its final performances in 1995. Conductors included Armin Jordan (Die Walküre in 1985), Manuel Rosenthal (1986) and Hermann Michael (1987, 1991 and 1995). Ring 3, 2000–2013: the production, which became known as the "Green" Ring, was in part inspired by the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest. Directed by Stephen Wadsworth, set designer Thomas Lynch, costume designer Martin Pakledinaz, lighting designer Peter Kaczorowski; Armin Jordan conducted in 2000, Franz Vote in 2001 and Robert Spano in 2005 and 2009. The 2013 performances, conducted by Asher Fisch, were released as a commercial recording on compact disc and on iTunes.[25]

In 2003 the first production of the cycle in Russia in modern times was conducted by Valery Gergiev at the Mariinsky Opera, Saint Petersburg, designed by George Tsypin. The production drew parallels with Ossetian mythology.[26]

The Royal Danish Opera performed a complete Ring cycle in May 2006 in its new waterfront home, the Copenhagen Opera House. This version of the Ring tells the story from the viewpoint of Brünnhilde and has a distinct feminist angle. For example, in a key scene in Die Walküre, it is Sieglinde and not Siegmund who manages to pull the sword Nothung out of a tree. At the end of the cycle, Brünnhilde does not die, but instead gives birth to Siegfried's child.[27]

In September 2006, the Canadian Opera Company opened its' new opera house, The Four Seasons Centre with a production of the Ring. Three cycles were presented with a different director overseeing an opera.

San Francisco Opera and Washington National Opera began a co-production of a new cycle in 2006 directed by Francesca Zambello. The production uses imagery from various eras of American history and has a feminist and environmentalist viewpoint. Recent performances of this production took place at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C. in April/May 2016, featuring Catherine Foster and Nina Stemme as Brünnhilde, Daniel Brenna as Siegfried and Alan Held as Wotan.[28]

Los Angeles Opera presented its first Ring cycle in 2010 directed by Achim Freyer.[29] Freyer staged an abstract production that was praised by many critics but criticized by some of its own stars.[30] The production featured a raked stage, flying props, screen projections and special effects.

The Metropolitan Opera began a new Ring cycle directed by French-Canadian theater director Robert Lepage in 2010. Premiering with Das Rheingold on opening night of the 2010/2011 Season conducted by James Levine with Bryn Terfel as Wotan. This was followed by Die Walküre in April 2011 starring Deborah Voigt. The 2011/12 season introduced Siegfried and Götterdämmerung with Voigt, Terfel and Jay Hunter Morris before the entire cycle was given in the Spring of 2012 conducted by Fabio Luisi (who stepped in for Levine due to health issues). Lepage's staging was dominated by a 90,000 pound (40 tonne) structure which consisted of 24 identical aluminium planks able to rotate independently on a horizontal axis across the stage, providing level, sloping, angled or moving surfaces facing the audience. Bubbles, falling stones and fire were projected on to these surfaces, linked by computer with the music and movement of the characters. The subsequent HD recordings in 2013 won the Met's orchestra and chorus the Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording for their performance.[31] In 2019, the Metropolitan Opera revived the Lepage staging for the first time since 2013 with Philippe Jordan conducting, Greer Grimsley and Michael Volle rotating as Wotan, Stefan Vinke and Andreas Schager rotating as Siegfried and Met homegrown Christine Goerke as Brünnhilde. Lepage's "Machine", as it affectionately became known, underwent major reconfiguration for the revival in order to dampen the creaking that it had produced in the past (to the annoyance of audience members and critics) and to improve its reliability, as it had been known to break down during earlier runs including on the opening night of Rheingold.[32][33][34] Unlike its beloved predecessor directed by Viennese opera director Otto Schenk which played at the house over 22 years,[35] the Met has confirmed that this controversial and expensive production will not return again, having lasted just shy of ten years at the house with only three complete cycles having been given. They announced it would be replaced by a new production in 2025, however though originally in partnership with the English National Opera this was cancelled due to ENO budgetary cuts and poor audience response.[36][37][38][39] In 2024 they announced director Yuval Sharon would instead direct a new production with the first installment set to premiere in the 27/28 season finishing with the full cycle in the Spring of 2030.[40]

The Lyric Opera of Chicago has staged three complete Ring Cycles in the past four decades, with a cycle in the 1990s, the 2000s, and in the late 2010s.

The mid-1990s production by August Everding with choreography by Cirque du Soleil's Debra Brown was conducted by Zubin Mehta, with James Morris a Wotan and Eva Marton as Brünnhilde, Siegfried Jerusalem as Siegmund, and Tina Kiberg as Sieglinde.[41]

The 2000s Ring cast included "James Morris as Wotan, Jane Eaglen as Brünnhilde, Plácido Domingo as Siegmund, and Michelle DeYoung as Sieglinde." Lyric music director Andrew Davis conduct[ed]. The company ... revived the August Everding production that it presented nine years [earlier], restaged by Herbert Kellner with minor changes ... The bungee-jumping Rhinemaidens and the Valkyries on trampolines from the original production, choreographed by Cirque du Soleil's Debra Brown ... returned. Sets and costumes [were] by John Conklin; lighting [was] by Duane Schuler."[42]

The most recent production's Das Rheingold premiered in 2016, with subsequent Ring operas Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung staged between 2017 and 2019. The subsequent "full Ring" performances in the spring of 2020 were cancelled due to the COVID-19 global pandemic and has never been staged at the Lyric as the complete cycle.

Opera Australia presented the Ring cycle at the State Theatre in Melbourne, Australia, in November 2013, directed by Neil Armfield and conducted by Pietari Inkinen. Classical Voice America heralded the production as "one of the best Rings anywhere in a long time."[43] The production was presented again in Melbourne from 21 November to 16 December 2016 starring Lise Lindstrom, Stefan Vinke, Amber Wagner and Jacqueline Dark.[44]

It is possible to perform The Ring with fewer resources than usual. In 1990, the City of Birmingham Touring Opera (now Birmingham Opera Company), presented a two-evening adaptation (by Jonathan Dove) for a limited number of solo singers, each doubling several roles and 18 orchestral players.[45] This version was subsequently given productions in the USA.[46] A heavily cut-down version (7 hours plus intervals) was performed at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires on 26 November 2012 to mark the 200th anniversary of Wagner's birth.[47]

In a different approach, Der Ring in Minden staged the cycle on the small stage of the Stadttheater Minden, beginning in 2015 with Das Rheingold, followed by the other parts in the succeeding years and culminating with the complete cycle performed twice in 2019. The stage director was Gerd Heinz, and Frank Beermann conducted the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, playing at the back of the stage. The singers acted in front of the orchestra, making an intimate approach to the dramatic situations possible. The project received international recognition.[48][49]

Recordings of the Ring cycle

[edit]Other treatments of the Ring cycle

[edit]Orchestral versions of the Ring cycle, summarizing the work in a single movement of an hour or so, have been made by Leopold Stokowski, Lorin Maazel (Der Ring ohne Worte) (1988) and Henk de Vlieger (The Ring: An Orchestral Adventure), (1991).[50]

English-Canadian comedian and singer Anna Russell recorded a twenty-two-minute version of the Ring for her album Anna Russell Sings! Again? in 1953, characterized by camp humour and sharp wit.[51][52]

Produced by the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, Charles Ludlam's 1977 play Der Ring Gott Farblonjet was a spoof of Wagner's operas. The show received a well-reviewed 1990 revival in New York at the Lucille Lortel Theatre.[53]

In 1991, Seattle Opera premiered a musical comedy parody of the Ring Cycle called Das Barbecü, with book and lyrics by Jim Luigs and music by Scott Warrender. It follows the outline of the cycle's plot but shifts the setting to Texas ranch country. It was later produced off-broadway and elsewhere around the world.

The German two-part television movie Dark Kingdom: The Dragon King (2004, also known as Ring of the Nibelungs, Die Nibelungen, Curse of the Ring and Sword of Xanten), is based in some of the same material Richard Wagner used for his music dramas Siegfried and Götterdämmerung.

An adaptation of Wagner's storyline was published as a graphic novel in 2002 by P. Craig Russell.[54]

The Ring cycle was the basis for a video game duology simply titled Ring, where each game adapts two of the four parts. The game reimagines the Ring cycle in a science fiction setting, and was very poorly received critically; although the first game was a financial success.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ also known as The Wanderer

References

[edit]- ^ "Wagner – Ring Cycle". Classic FM. 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ von Rhein, John (21 September 2016). "An epic beginning for Lyric's new Wagner 'Ring' cycle". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Magee 2001, p. 109.

- ^ "Wagner in Russia: Ringing in the century". The Economist. 12 June 2003. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "Das Rheingold (Opera) Characters". StageAgent. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Die Walküre (Opera) Characters". StageAgent. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Siegfried (Opera) Characters". StageAgent. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ "Götterdämmerung (Opera) Characters". StageAgent. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ For a detailed examination of Wagner's sources for the Ring and his treatment of them, see, among other works, Deryck Cooke's unfinished study of the Ring, I Saw the World End (Cooke 2000), and Ernest Newman's Wagner Nights. Also useful is a translation by Stewart Spencer (Wagner's 'Ring of the Nibelung': Companion, edited by Barry Millington) which, as well as containing essays, including one on the source material which provides an English translation of the entire text that strives to remain faithful to the early medieval Stabreim technique Wagner used.

- ^ Wagner (1994), p. 287.

- ^ Wagner (1994), pp. 336–337.

- ^ Wagner (1994), p. 391 and n..

- ^ Burbidge & Sutton (1979), pp. 345–346.

- ^ Millington (2008), p. 80.

- ^ Shaw (1898), section: "Back to Opera Again".

- ^ "The Instruments of the RING". www.lyricopera.org. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Letter of 9 December 1840. See Mendelssohn (1987), pp. 299–301

- ^ Fifield (2005), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Boydell and Brewer (2 December 2008). "From Beyond the Stave: The Lion roars for Wagner". Frombeyondthestave.blogspot.com. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Murphy, Kerry (2014). "Thomas Quinlan and the 'All Red' Ring: Australia, 1913" (PDF). Context: Journal of Music Research (39). University of Melbourne: 79–88 (82–84). ISSN 1038-4006. " 'Wagner and Us' Symposium"

- ^ "Productions – Wieland Wagner, New Bayreuth". Wagner Operas. 3 March 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "The 1976 Bayreuth Centennial Ring", Wagneropera.com, retrieved 2 December 2011

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (7 October 2013). "Patrice Chéreau, Opera, Stage and Film Director, Dies at 68". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Millington, Barry (8 October 2013). "Patrice Chéreau and the bringing of dramatic conviction to the opera house". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ Ring performances, Seattle Opera

- ^ "Mariinsky Theatre brings Ring Cycle to Covent Garden in Summer 2009" Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Musicalcriticism.com 1 March 2009, retrieved 1 December 2011

- ^ "The Royal Danish Theatre - der Ring des Nibelungen". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Ring Cycle". John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. 22 May 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Diane Haithman (15 February 2009). "Achim Freyer is consumed by The Ring of the Nibelung". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Adams, Guy (15 May 2010). "Wagner star and director clash in US costume drama". The Independent. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "55th Annual Grammy Awards Nominees: Classical". Grammy.com. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Everything You Need to Know About the Met Opera's 2018-19 Revival of Wagner's Ring Cycle". Opera Wire. 15 February 2018.

- ^ Goodwin, Jay (7 March 2019). "The Met Opera Revives Robert LePage's Hi-Tech Staging of Wagner's Ring Cycle". Playbill.

- ^ Cooper, Michael (21 September 2018). "Retooling the Met Opera's Problematic Ring Machine". The New York Times.

- ^ "Traditional Ring Begins Its Finale" by Anthony Tommasini, 26 March 2009, The New York Times

- ^ "Review: This London Ring Is on the Met Opera's Radar" by Zachary Woolfe, 12 September 2023, The New York Times

- ^ "The Stakes Are Sky-High for a Ring Coming to the Met Opera" by Matthew Anderson, 12 November 2021, The New York Times

- ^ "Future of Metropolitan Opera's New Ring Cycle Uncertain Due to ENO Budget Cuts" by David Salazar, Opera Wire, 17 January 2023 Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Review: The Met Opera's Next Ring Will Be a Sea Change" by Zachary Woolfe, 21 November 2021, The New York Times

- ^ [1] playbill.com

- ^ Tribune, Chicago Tribune | Chicago (25 November 1993). "'RING' MASTERY". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ Mattison, Ben (28 March 2005). "Lyric Opera of Chicago Opens Ring Cycle". Playbill. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "Bedeviled Ring Seemed Doomed, Then Curtain Rose". Classicalvoiceamerica.org. 14 December 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "It's a Wrap: The Melbourne Ring". Classic Melbourne. 21 December 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "The Ring Saga". birminghamopera.org.uk. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Croan, Robert (18 July 2006). "Opera Review: Abridged staging of classic Wagner cycle rings true – Pittsburgh Post-Gazette". post-gazette.com. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Samira Schellhaaß (27 September 2012). "The Ring in Teatro Colón". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Oehrlein, Josef (27 September 2019). "Der Kleine muss Ideen haben / Zeitreise durch vier Epochen: Richard Wagners "Ring" in Minden". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Frankfurt. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Brockmann, Sigi (8 October 2019). "Minden / Stadttheater: Der Ring des Nibelungen – jetzt das gesamte Bühnenfestspiel". Der Neue Merker (in German). Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "Arquivo.pt". www.schott-music.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- ^ "Anna Russell's Ring". Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "The Ring of the Nibelungs (An analysis)". YouTube. 9 September 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (13 April 1990). "Review/Theater; Just a Song at Twilight (of the Gods)". The New York Times (Der Ring Gott Farblonjet review).

- ^ Russell, P. Craig (2018). The Ring of the Nibelung. Milwaukie, Oregon: Dark Horse Books. ISBN 978-1-5067-0919-2.

Sources

[edit]- Burbidge, Peter; Sutton, Richard (1979). The Wagner Companion. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-11450-4.

- Cooke, Deryck (2000). I Saw the World End: A Study of Wagner's Ring. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315318-1.

- Fifield, Christopher (2005). Ibbs and Tillett: The Rise and Fall of a Musical Empire. London: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-84014-290-7.

- Magee, Bryan (2001). The Tristan chord: Wagner and Philosophy. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-6788-4.

- Mendelssohn, Fanny (1987). Marcia Citron (ed.). Letters of Fanny Hensel to Felix Mendelssohn. Pendragon Press. ISBN 978-0-918728-52-4.

- Millington, Barry (2008). "Der Ring des Nibelungen: conception and interpretation". In Grey, Thomas S. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Wagner. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–84. ISBN 978-0-521-64439-6.

- Shaw, George Bernard (1898). The Perfect Wagnerite. Retrieved 29 April 2017 – via Project Gutenberg.

- Wagner, Richard (1994). The Art Work of the Future and Other Works ("A Communication to My Friends" is on pp. 269–392.). Translated by William Ashton Ellis. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9752-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Besack, Michael, The Esoteric Wagner: An Introduction to Der Ring des Nibelungen, Berkeley: Regent Press, 2004 ISBN 978-1-58790-074-7.

- Di Gaetani, John Louis, Penetrating Wagner's Ring: An Anthology. New York: Da Capo Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0-306-80437-3.

- Foster, Daniel, (2010) Wagner's Ring Cycle and the Greeks. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-51739-7.

- Gregor-Dellin, Martin, (1983) Richard Wagner: His Life, His Work, His Century. Harcourt, ISBN 0-15-177151-0.

- Holman, J. K. Wagner's Ring: A Listener's Companion and Concordance. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 2001.

- Lee, M. Owen, (1994) Wagner's Ring: Turning the Sky Round. Amadeus Press, ISBN 978-0-87910-186-2.

- Magee, Bryan, (1988) Aspects of Wagner. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-284012-6.

- May, Thomas, (2004) Decoding Wagner. Amadeus Press, ISBN 978-1-57467-097-4.

- Millington, Barry (editor) (2001) The Wagner Compendium. Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28274-9.

- Sabor, Rudolph, (1997) Richard Wagner: Der Ring des Nibelungen: a companion volume. Phaidon Press, ISBN 0-7148-3650-8.

- Scruton, Sir Roger, (2016) The Ring of Truth: The Wisdom of Wagner's Ring of the Nibelung. Penguin UK. ISBN 1-4683-1549-8.

- Spotts, Frederick, (1999) Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-7126-5277-9.

- Vernon, David, (2021) Disturbing the Universe: Wagner's Musikdrama. Edinburgh: Candle Row Press. ISBN 978-1-5272-9924-5.

External links

[edit]- Anthony Tommasini (21 July 2007). "The 'Kirov' Ring: Let's Hear It for the Home Team". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "The Ring and I". Radiolab. WNYC. 2004. A podcast about The Ring.

Der Ring des Nibelungen

View on GrokipediaOverview

Cycle Structure and Duration

Der Ring des Nibelungen forms a tetralogy of operas, with Das Rheingold serving as the Vorabend (preliminary evening) without traditional acts or intermissions, followed by the three principal evenings—Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung—each divided into three acts.[5] Wagner intended the cycle for sequential performance over four evenings in a festival setting, as realized at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, though individual operas are sometimes staged separately.[10] The structure emphasizes continuity through leitmotifs and narrative progression, treating the work as a unified Bühnenfestspiel (stage festival play).[11] The total musical duration approximates 15 hours, excluding intermissions, though actual performance times extend longer due to breaks—typically one hour each between acts at venues like Bayreuth.[5] [2] [12] Das Rheingold lasts about 2 hours 30 minutes continuously, while the subsequent operas require 4 to 4 hours 30 minutes each, accommodating orchestral complexity and vocal demands.[13] [14] Variations occur by conductor's tempo and production choices, with some cycles exceeding 16 hours in performance.[1]Historical and Cultural Significance

Der Ring des Nibelungen premiered as a complete cycle at the Bayreuth Festival from August 13 to 17, 1876, in the purpose-built Festspielhaus, marking the realization of Richard Wagner's vision for a dedicated theater optimized for his operas through innovations like the hidden orchestra pit.[15] This event, funded partly by Ludwig II of Bavaria and attended by figures such as Kaiser Wilhelm I, represented a pinnacle of 19th-century German cultural ambition, embodying Wagner's concept of Gesamtkunstwerk—a synthesis of music, drama, poetry, and visual arts into a unified art form.[7] The cycle's creation spanned over 25 years, with composition beginning in 1848 amid Wagner's involvement in the failed Dresden uprising, reflecting Romantic ideals of myth and national identity drawn from Germanic sources.[1] The work's innovations, including the extensive use of leitmotifs—recurring musical themes associated with characters, ideas, or objects—profoundly influenced subsequent opera, symphonic music, and even film scoring, as seen in the thematic development techniques employed by composers like Richard Strauss and later in cinematic works by John Williams.[16] Its emphasis on continuous music without traditional arias and the integration of advanced stage technology, such as hydraulic lifts for scene changes, advanced theatrical production standards that persist in modern opera houses.[17] Culturally, the cycle reinforced German nationalist sentiments during unification under Bismarck, portraying mythic struggles as allegories for power, renunciation, and societal renewal, though Wagner's own writings linked these to critiques of materialism and Jewish influence in culture.[18] Posthumously, the Ring's association with Adolf Hitler—who revered Wagner and attended Bayreuth festivals—has overshadowed its legacy, leading to performances being boycotted by some Jewish artists and institutions, despite Wagner's death in 1883 predating Nazism by decades and the operas themselves containing no explicit ideological alignment with Nazi doctrine.[19] Scholarly analysis distinguishes the work's nationalistic mythology, rooted in pre-modern legends, from its appropriation by the Third Reich for propaganda, noting that while Hitler's worldview echoed Wagner's themes of heroic destiny and cultural purity, the composer's music dramas critiqued tyranny and celebrated redemption through love rather than racial supremacy.[20] This nuance underscores the Ring's enduring significance as a cornerstone of Western art music, performed annually at Bayreuth and worldwide, influencing interdisciplinary explorations of myth in literature, psychology, and philosophy.[21]Mythological and Literary Sources

Norse and Germanic Legends

The Norse legends inspiring elements of Der Ring des Nibelungen primarily stem from the Völsunga Saga, a 13th-century Icelandic prose narrative compiled from earlier oral traditions and poetic sources like the Poetic Edda. This saga traces the doomed lineage of the Völsung clan, favored yet cursed by Odin, beginning with Sigi, Odin's son, and emphasizing themes of fate, vengeance, and supernatural intervention. Odin plants the sword Gram in the Branstock tree, which only Sigmund retrieves, forging his heroism before his betrayal and death by Odin's spear; his son Sigurd later reforges the blade to slay the dragon Fafnir, guardian of a cursed hoard originally amassed by the dwarf Andvari.[22][23] Central to the Norse hoard narrative is the theft by Loki, who, after slaying Otter (son of the shape-shifter Hreidmar), compels Andvari to surrender his gold—including the multiplying ring Andvaranaut—as wergild, prompting Andvari's curse of perpetual misfortune upon possessors. Sigurd acquires this treasure by killing Fafnir, transformed from Hreidmar's avaricious son Regin, and tastes the dragon's blood, gaining prophetic wisdom from birds warning of Regin's treachery, whom he then beheads. The saga intertwines this with Sigurd's awakening of the Valkyrie Brynhild (Sigrdrífa in the Edda), their mutual oath, and his subsequent amnesia induced by a potion from the Niflung sisters, leading to marriage with Gudrun, Brynhild's manipulated suicide, and the hoard's dissemination amid familial blood feuds.[22][23] Germanic legends, particularly the Nibelungenlied, a Middle High German epic poem from around 1200 attributed to an anonymous Austrian poet, shift focus to a more secular, chivalric framework centered on the historical Burgundian royal house. Siegfried, a prince from Xanten, amasses the Nibelung treasure by slaying dragons and dwarves, then aids King Gunther of Worms in wooing the Icelandic queen Brunhild via a cloak of invisibility, secretly subduing her strength. Betrayed by Hagen of Tronje, who murders Siegfried at Kriemhild's bath (his vulnerable spot marked by a leaf), the hoard is sunk in the Rhine to evade her control; years later, widowed Kriemhild marries Etzel (Attila) of the Huns, luring the Burgundians to her vengeful massacre, where she slays Hagen but perishes in the ensuing chaos.[22][24] These legends, preserved in manuscript traditions like the Codex Regius for the Edda (c. 1270) and early Nibelungenlied fragments from the 1230s, reflect pre-Christian pagan motifs adapted in Christian-era Iceland and the Holy Roman Empire, with the Norse emphasizing divine fatalism and the Germanic highlighting feudal loyalty and retribution.[22]Wagner's Adaptations and Innovations

Wagner synthesized elements from the Völsunga Saga, the Poetic and Prose Eddas, and the Nibelungenlied to create a cohesive narrative spanning divine and human realms, diverging from the fragmented, primarily heroic focus of the medieval sources. While the Völsunga Saga centers on the Volsung clan's tragedies without integrating the gods' cosmic fate, Wagner fused this with Eddic accounts of Ragnarök and the Aesir's downfall, positioning the ring's curse as the catalyst for both heroic downfall and Götterdämmerung. [1] [25] The Nibelungenlied, a 13th-century German epic emphasizing courtly intrigue among mortals like the Burgundians, provided motifs such as the hoard and Hagen's treachery, but lacked supernatural elements like the ring's world-dominating power; Wagner innovated by elevating the artifact—forged from Rhinegold after Alberich's renunciation of love—to embody absolute rule and inevitable doom, absent in the saga's mere cursed treasure. [26] [27] Key plot alterations underscore Wagner's emphasis on causality and moral decay over fatalistic heroism. In the Völsunga Saga, Sigurd slays Fafnir, claims the hoard, and awakens Brynhildr with full mutual recognition, leading to her vengeful aid after betrayal; Wagner's Siegfried, amnesiac from a potion, unwittingly weds Gutrune, transforming Brynhildr's (Brünnhilde's) role into one of tragic disillusionment and redemptive immolation, which precipitates the gods' extinction rather than mere clan extinction. [28] Wagner introduced Wotan's contractual obsessions and the spear's treaties as drivers of divine vulnerability, expanding Odin's Eddic wisdom-seeking into a fatal compromise with power, while omitting the saga's surviving lineages to enforce total cataclysm. [29] Brünnhilde's defiance, drawn from her Valkyrie disobedience in the Poetic Edda's Helreið Brynhildar, evolves into Wagner's innovation of her as Wotan's estranged will, embodying renunciation as the path to transcendence. [25] These changes reflect Wagner's imposition of 19th-century philosophical realism, prioritizing the gods' self-inflicted decline through treaties and hoarding over the Eddas' cyclical, amoral cosmos. The ring's theft by Loki (Loge) from Alberich parallels Andvari's curse in the Prose Edda, but Wagner amplified it into a love-forsaking pact, symbolizing modernity's Faustian bargains, and resolved it via Brünnhilde's voluntary return to the Rhine—contrasting the sagas' unresolved greed cycles. [30] Character Germanizations, such as Sigurd to Siegfried and Gudrun to Gutrune, aligned the tale with national mythic revival, while the absence of Christian redemption arcs in originals preserved pagan causality, critiquing power's corrupting logic. [31] This synthesis, begun in Wagner's 1848 prose sketch Der Nibelunge and refined through 1852 libretto drafts, prioritized dramatic unity and thematic depth over source fidelity. [29]Characters

Gods and Valkyries

The gods in Der Ring des Nibelungen form the divine hierarchy ruling over the world from Valhalla, with Wotan as the supreme authority and king of the gods, characterized by his ambition for power manifested through treaties inscribed on a spear and his pursuit of the ring of power.[5][32] Wotan's wife, Fricka, embodies the goddess of marriage and domestic order, frequently confronting Wotan over violations of oaths and familial bonds, as seen in her insistence on upholding contracts that conflict with Wotan's desires.[5][33] Supporting deities include Loge, the fire god and cunning counselor to Wotan, who introduces the concept of renunciation to resolve the gods' dilemmas regarding the stolen gold but ultimately withdraws from divine affairs.[32] Donner, god of thunder, wields a hammer to summon storms and aids in defending the gods, while his brother Froh represents light and fertility, contributing to the restoration of Freia, the goddess of love and youth whose golden apples sustain the gods' immortality.[32][33] The Valkyries serve as warrior maidens and daughters of Wotan and the earth goddess Erda, tasked with riding into battlefields to claim fallen heroes for Valhalla, thereby bolstering the gods' forces against eventual threats.[34] Brünnhilde, the most prominent Valkyrie, acts as Wotan's favored will, initially obeying his commands to intervene in human affairs but later defying him to protect the Volsung hero Siegmund, leading to her punishment and central role in the cycle's unfolding tragedy.[35][36] Brünnhilde's eight sisters—Gerhilde, Ortlinde, Waltraute, Schwertleite, Helmwige, Siegrune, Grimgerde, and Roßweiße—appear collectively in the "Ride of the Valkyries" scene of Die Walküre, where they gather heroes and reveal their familial ties and duties amid boisterous camaraderie before Brünnhilde's solo narrative dominates.[34][37] Waltraute reappears in Götterdämmerung to implore Brünnhilde to return the ring and avert catastrophe, underscoring the Valkyries' diminishing relevance as the gods' power wanes.[37]Heroes and Humans

The human heroes of Der Ring des Nibelungen are centered on the Wälsung family, embodying themes of forbidden love, heroism, and tragic destiny. Siegmund, a tenor role portraying Wotan's mortal son and a fugitive warrior, seeks refuge in the home of Hunding during a storm, where he discovers his twin sister Sieglinde, also Wotan's daughter and a soprano.[38] Their unrecognized sibling bond ignites a passionate union, symbolizing defiance against divine and social prohibitions, before Siegmund's death in combat at Wotan's command.[2] Siegfried, the son of Siegmund and Sieglinde and himself a tenor, represents the cycle's ideal of untainted human potential, raised in isolation by the Nibelung dwarf Mime after his mother's death. Lacking fear and guided by instinct, he reforges the shattered sword Notung, slays the dragon Fafner to claim the ring, and awakens Brünnhilde from her enchanted sleep, forging a bond of mutual liberation. Wagner envisioned Siegfried as the "most perfect human being" and a figure of future redemption, though his naivety leads to manipulation and downfall.[39][40] In contrast, the Gibichungs introduce elements of political ambition and familial deceit among humans. Gunther, king of the Gibichungs and a baritone, aspires to heroic status through alliances, enlisting Siegfried via a potion to win Brünnhilde as his bride while pledging Gutrune, his soprano sister, to Siegfried. Hagen, their bass-baritone half-brother and Alberich's son, drives the intrigue with paternal curses urging ring reclamation, culminating in Siegfried's betrayal and murder. These characters underscore Wagner's critique of calculated power devoid of genuine heroism.[41][42]Dwarves, Giants, and Other Beings

The Nibelungs constitute a subterranean race of dwarves skilled in metalworking and residing in Nibelheim, where they forge treasures under duress after Alberich's conquest.[33] Alberich, their ruler and a Nibelung dwarf, renounces love to seize the Rhinegold from its guardians, forging it into a ring that grants dominion over others but curses its bearers with greed and doom.[1] His brother Mime, another Nibelung dwarf, crafts the Tarnhelm—a magical helmet enabling shape-shifting and invisibility—and later reforges the sword Notung for the hero Siegfried, intending to exploit him to reclaim the ring from Fafner.[43] [44] The giants Fasolt and Fafner, immense builders contracted by Wotan to erect Valhalla, demand the goddess Freia as payment but accept a hoard of gold and the ring to cover her instead; Fasolt, enamored with Freia, is slain by the more ruthless Fafner in a fratricidal quarrel over the ring.[43] [5] Fafner subsequently uses the Tarnhelm to transform into a dragon, guarding the treasure in a cave until Siegfried slays him.[45] Among other supernatural entities, the Rhinemaidens—Woglinde, Wellgunde, and Flosshilde—serve as water nymphs tasked with safeguarding the Rhinegold in the river's depths, taunting Alberich before his theft and later attempting to reclaim the ring from Hagen in Götterdämmerung.[5] Erda, the primordial earth goddess, emerges to warn Wotan of the ring's perils and the gods' impending downfall, bearing the Norns as daughters and influencing his fateful decisions.[1] The three Norns, Erda's offspring, weave the rope of fate at the world's root in the prologue to Götterdämmerung, foretelling the cycle's catastrophic end as their thread snaps.[1]Plot Summary

Das Rheingold

Das Rheingold, the prologue to Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, unfolds in four continuous scenes without intermission, establishing the cycle's central conflict over the Rhine gold and the forged ring of power.[46] The opera opens with an extended orchestral prelude depicting the depths of the Rhine River, where the Rhine gold lies dormant, illuminated only when disturbed.[47] Scene 1 takes place at the bottom of the Rhine, where the three Rhinemaidens—Woglinde, Wellgunde, and Flosshilde—frolic and guard the gold. The Nibelung dwarf Alberich arrives, lusting after the maidens, who tease and reject him. In frustration, Alberich learns from them that the gold can be forged into a ring granting unlimited power, but only if the forger renounces love forever. Cursing love, Alberich seizes the gold and flees to his underground realm of Nibelheim.[43][46] Scene 2 shifts to an open mountaintop at dawn, overlooking the newly completed gods' fortress Valhalla. Wotan, chief of the gods, awakens beside his wife Fricka and reflects on the fortress built by the giants Fasolt and Fafner in exchange for Freia, goddess of youth and sister to Fricka. As the giants demand payment, the fire god Loge arrives with news of the gold's theft. Wotan, prompted by Loge, agrees to retrieve the gold from Alberich to ransom Freia, whose absence causes the gods to age. Accompanied by Loge, Wotan descends to Nibelheim.[43][45] Scene 3 occurs in Nibelheim, where Alberich has used the gold to forge the ring and a magic helmet (Tarnhelm), enslaving the Nibelungs with its power to rule and shape-shift. Loge lures Alberich into demonstrating the Tarnhelm's powers, allowing Wotan and Loge to seize it and force Alberich to yield the hoard. Wotan demands and takes the ring, despite Alberich's curse upon it, invoking ruin for any possessor. The pair fills a chest with the gold to match Freia's height, including the Tarnhelm.[48][46] Scene 4 returns to the mountaintop, where the giants hold Freia hostage. Wotan offers the hoard in her place, but Fafner demands it pile high enough to conceal her. When Loge reveals the missing ring, Wotan reluctantly surrenders it. Fasolt momentarily covets the ring, leading Fafner to kill him and claim it, enacting the curse's first toll. The earth goddess Erda emerges briefly to warn Wotan of the ring's peril and the doom it foretells for the gods. Troubled, Wotan descends with Loge to consult Erda further as the Rhinemaidens' lament echoes, and the gods enter Valhalla amid unresolved omens.[43][45]Die Walküre

Die Walküre (The Valkyrie) is the second opera in Richard Wagner's tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen, premiered on June 26, 1870, at the Königliches Hof- und Nationaltheater in Munich under the direction of Franz Wüllner, though Wagner had intended it for Bayreuth.[49] The libretto, written by Wagner himself, draws from Norse sagas including the Völsunga saga and Poetic Edda, adapting the tale of the twins Siegmund and Sieglinde, offspring of Wotan, whose forbidden union defies divine and mortal laws.[50] The opera explores themes of fate, incestuous love, paternal conflict, and the erosion of godly authority, with Wotan's favored daughter Brünnhilde defying her father to protect human agency.[38] The narrative unfolds in three acts set in mythical prehistoric times. In Act I, Siegmund, pursued by enemies after fleeing a failed clan battle, seeks refuge during a storm in a rural dwelling belonging to Hunding, where he encounters Sieglinde, Hunding's unwilling wife.[35] An immediate mutual attraction reveals their shared Volsung heritage—Siegmund recounts his youth spent wandering with his father Wälse (Wotan in disguise) after enemies slew his mother and abducted his twin sister, unknowingly Sieglinde herself.[51] Sieglinde, drugged by Hunding upon his return, reveals a sword embedded in an ash tree by her hearth, planted by Wälse as a token for the destined hero; Siegmund, recognizing his fate, withdraws the blade, named Nothung, and the twins consummate their incestuous bond as Hunding sleeps, vowing to challenge him. Act II opens on a mountain peak where Wotan instructs his Valkyrie daughter Brünnhilde to ensure Siegmund's victory in combat, viewing him as the free hero needed to reclaim the ring from Fafner without violating treaties.[35] His wife Fricka, goddess of marriage, intervenes, condemning the twins' incest as a breach of her sacred vows and demanding Siegmund's death to preserve divine order, forcing Wotan to relent in anguish over his self-imposed constraints.[50] Brünnhilde, witnessing Sieglinde's despair and learning of her pregnancy with Siegmund's child, disobeys by shielding Siegmund during his duel with Hunding; Wotan shatters Nothung mid-swing, allowing Hunding to slay Siegmund, whom Wotan then kills to honor Fricka's decree, while Brünnhilde rescues the shattered sword fragments and fleeing Sieglinde, entrusting her with the unborn Siegfried's destiny.[49] In Act III, the Valkyries convene atop a rocky summit, gathering slain heroes for Valhalla, but Brünnhilde arrives seeking aid to hide Sieglinde from Wotan's wrath; her sisters refuse, fearing punishment.[38] Wotan arrives, enraged, and despite Brünnhilde's plea that her defiance stemmed from his own unspoken will for human freedom, he strips her immortality, sentencing her to mortal sleep protected atop a fire-ringed crag, to be claimed by a fearless hero as his bride.[51] In a protracted farewell, Wotan bids adieu to his once-favored child, summoning Loge to encircle the rock in flames, as Brünnhilde awakens to her new vulnerability, embracing her fate.[35]Siegfried

Siegfried, the third music drama in Richard Wagner's tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen, continues the narrative following Die Walküre, focusing on the youthful hero Siegfried's forging of his sword, slaying of the dragon Fafner, acquisition of the ring, and awakening of Brünnhilde.[52] The opera, scored for a large orchestra including expanded brass and percussion sections, unfolds in three acts without traditional breaks, emphasizing continuous musical flow through leitmotifs.[52] Act 1 takes place in Mime's forest cave, where the Nibelung dwarf Mime labors to forge a sword for his foster son Siegfried, whom he despises yet needs to kill Fafner and retrieve the ring and hoard.[52] Siegfried, ignorant of fear and rejecting Mime's inadequate blade, demands knowledge of his origins; Mime reveals he found the infant Siegfried with his dying mother Sieglinde and the shattered sword Nothung fragments.[52] A riddle contest ensues with Wotan disguised as the Wanderer, who prophesies that the fearless one will claim Mime's life; Siegfried then reforges Nothung himself, shatters the anvil, and sets forth to confront Fafner.[52] Act 2 shifts to the vicinity of Fafner's cave, where Alberich curses the ring and urges Fafner to defend it, only to be warned by the Wanderer of impending doom from Siegfried.[52] Siegfried, guided by Mime, arrives, slays the dragon Fafner with Nothung after a dramatic orchestral battle, and tastes the dragon's blood, granting him understanding of the forest bird's song, which reveals Mime's treachery—he then strikes down Mime with the sword.[52] Directed by the bird to a sleeping rock-enclosed figure, Siegfried claims the ring and Tarnhelm from Fafner's hoard before ascending the mountain.[52] Act 3 opens on a mountain pass where the Wanderer summons Erda, who foretells the gods' twilight, prompting Wotan to embrace inevitable downfall.[52] Siegfried encounters the Wanderer, whose spear is shattered by Nothung in confrontation, allowing the hero to pass to Brünnhilde's fiery summit.[52] There, Siegfried penetrates the flames, removes Brünnhilde's armor, and awakens her with a kiss; initially resisting due to her Valkyrie vows, she yields to mortal love, renouncing immortality as they unite in ecstatic duet.[52] The opera premiered on August 16, 1876, at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus as part of the first complete Ring cycle.[52]Götterdämmerung

PrologueAt night atop the Valkyries' rock, the three Norns—daughters of the earth goddess Erda—weave the rope of destiny while recounting events from the cycle's past, including Wotan's use of the world ash tree to fashion his spear and his subsequent commands to the giants Fasolt and Fafner.[41] They foresee the downfall tied to the Nibelung's ring, but the rope breaks as the knowledge of the gods wanes, and the Norns sink back into the earth.[41] [53] Dawn breaks, revealing Siegfried and Brünnhilde; she removes her protective armor's magic from him, entrusting the ring he once gave her to safeguard their love, and sends him forth on adventures with her horse Grane, while retaining the ring herself.[41] [54] Act One

In the hall of the Gibichungs on the Rhine, Gunther aspires to a worthy bride, and his half-brother Hagen—son of Alberich—advises him to seek Brünnhilde, suggesting the hero Siegfried could win her through the Tarnhelm's shape-shifting power.[41] Hagen schemes to secure the ring for his father. Gunther's sister Gutrune offers Siegfried a potion of forgetfulness upon his arrival by boat; he drinks it, loses memory of Brünnhilde, falls in love with Gutrune, and swears blood-brotherhood with Gunther before departing—disguised as Gunther via the Tarnhelm—to claim Brünnhilde and her ring.[41] [53] Siegfried seizes Brünnhilde, who resists, and takes the ring from her finger, returning with her to the Gibichung hall.[41] Act Two

Outside the Gibichung hall, Hagen summons Alberich, who urges him to seize the ring, but Hagen feigns loyalty.[41] Brünnhilde arrives with Gunther, horrified to see Siegfried with Gutrune and wearing the ring she thought protected their bond; she denounces him as a betrayer.[41] Siegfried, unaffected by her accusations due to the potion, recounts his feats truthfully but claims no knowledge of her. Hagen proposes a trial by oath, which Siegfried swears falsely on his sword Notung, and Brünnhilde reveals the sword's vulnerability to Hagen.[41] She conspires with Hagen and Gunther to murder Siegfried, prioritizing vengeance over the ring.[41] Act Three

In the woods by the Rhine, the Rhinemaidens beseech Siegfried to return the ring, warning of his doom, but he refuses, mocking their pleas.[41] [55] Hunting parties arrive; Hagen administers an antidote potion to Siegfried, restoring his memory, and Siegfried recounts his life story, including awakening Brünnhilde. Hagen stabs him in the back with a spear fragment at Notung's vulnerable point.[41] Siegfried dies envisioning Brünnhilde as the Rhinemaidens reclaim the ring's curse. His body is borne to the hall, where Brünnhilde, enlightened, defies Hagen's claim on the ring, builds a pyre, mounts it with Siegfried and Grane, and immolates herself.[41] The pyre's flames engulf Valhalla; Wotan and the gods perish as the Rhine overflows, the Rhinemaidens drown Hagen while retrieving the ring, restoring it to the waters, ending the curse's dominion.[41] [53]

Music and Structure

Leitmotifs and Motivic Development

Leitmotifs constitute a central innovation in Der Ring des Nibelungen, consisting of concise musical phrases that recur to evoke specific characters, objects, events, emotions, or abstract concepts, thereby providing structural cohesion and psychological depth across the tetralogy.[56] Unlike sporadic thematic recalls in earlier operas, Wagner integrates them symphonically, allowing motifs to emerge organically from the orchestral fabric to underscore dramatic action and foreshadow narrative turns.[57] The technique, which Wagner termed "melodic moments of feeling" rather than leitmotifs, draws from his theoretical framework in Opera and Drama (1852), where he advocated motifs as musical realizations of poetic intent, evolving through association rather than isolated aria-like structures.[6] The term "leitmotif" originated with Hans von Wolzogen's 1876 Thematischer Leitfaden durch die Musik zu Richard Wagners Der Ring des Nibelungen, which cataloged recurring themes in the cycle to aid audience comprehension during Bayreuth performances.[58] Scholars estimate the total number variably due to interpretive boundaries between distinct motifs and their variants; detailed analyses identify anywhere from 80 to over 170, with one comprehensive enumeration listing 178 motifs, including rhythmic patterns, chordal figures, and melodic fragments.[59] Motifs span types such as character themes (e.g., the heroic Siegfried motif, a bold horn call introduced in Siegfried Act I), object associations (e.g., the Ring motif, a sinuous descending line symbolizing cursed power, first heard in Das Rheingold Scene 1), and idea complexes (e.g., the renunciation of love motif, linked to Alberich's theft of the gold).[57][60] Motivic development propels the cycle's continuous musical flow, with motifs undergoing transformation via melodic extension, harmonic alteration, rhythmic variation, or orchestration shifts to mirror character evolution and plot progression.[57] For instance, the primal Nature motif—a luminous major triad in the strings at the opera's opening—spawns derivatives like the Rhine daughters' flowing figures and later Erda's ominous depths, illustrating causal progression from elemental harmony to foreboding dissolution.[57] Similarly, Wotan's Spear motif, a stern dotted rhythm evoking authority and treaties in Das Rheingold, fragments and intensifies in Die Walküre to convey his tormented will, eventually combining with fate and renunciation themes in Götterdämmerung to depict cosmic reckoning.[57] These combinations forge extended symphonic developments, such as the forging scene in Siegfried Act I, where the Sword (Nothung) motif fuses with anvil rhythms to symbolize heroic emergence from primal forces.[58] Such developments enable leitmotifs to function as narrative agents, recalling past events with altered inflection to reveal subconscious motivations—e.g., the Twilight of the Gods motif, derived from earlier Valhalla splendor, returns distorted in Götterdämmerung to signal inevitable downfall.[57] Empirical studies confirm listeners perceive these associations, with recognition rates increasing for frequently recurring motifs, supporting Wagner's intent for motifs to subconsciously guide emotional response amid the work's 15-hour span.[61] Organized into families (e.g., Ring family encompassing curse, greed, and redemption variants), the motifs underpin the tetralogy's through-composed form, eschewing traditional numbers for a seamless orchestral discourse that parallels symphonic sonata principles while advancing mythic causality.[57][60] This rigorous motivic web not only unifies disparate operas but also embodies Wagner's vision of music as causal driver of drama, where thematic evolution mirrors the inexorable logic of power's corruption and renewal.[57]Orchestration and Instrumentation

Wagner scored Der Ring des Nibelungen for a large orchestra of roughly 90 players, emphasizing timbral depth and dynamic flexibility to support the cycle's leitmotifs and dramatic scope. This ensemble features doubled or tripled woodwind sections, an augmented brass contingent with novel instruments, extensive percussion, and multiple harps, enabling layered textures and coloristic effects unprecedented in opera.[62] The woodwind section includes three flutes (one doubling piccolo), three oboes (one doubling cor anglais), three clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), and three bassoons, providing agility for motivic interplay and atmospheric underscoring, such as the shimmering Rhine motifs in Das Rheingold.[63] The brass section, greatly expanded for power and blend, comprises eight horns (with the fifth through eighth often played on Wagner tubas), three trumpets (one bass trumpet), three tenor trombones, one contrabass trombone, and contrabass tuba. Wagner invented the Wagner tuba—a valved, conical-bore instrument akin to a tenor horn but larger, in two tenor (B♭) and two bass (F) variants—to fill a perceived gap between horns and trombones, fostering a cohesive brass timbre for heroic and mythic passages.[62][64] Strings form a robust foundation with 16–18 first violins, 16 second violins, 12 violas, 12 cellos, and 8–10 double basses, sustaining continuous motivic development amid vocal lines. Harp sections reach six players in scenes like the Rhinemaidens' appeals, their glissandi evoking otherworldly allure. Percussion is vast, incorporating six timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, tam-tam, and specialized effects such as 18 anvils in Siegfried's forging scene, thunder machines, and offstage steer horns for cosmic resonance.[65] Antiphonal offstage brass ensembles further enhance spatial drama, particularly in Götterdämmerung's immolation. These elements collectively realize Wagner's vision of the orchestra as a "universal" expressive force, integrating voices into a symphonic whole.[62]Harmony, Tonality, and Form

Der Ring des Nibelungen is structured as a through-composed music drama, eschewing the number-based forms of traditional opera in favor of continuous musical development that mirrors the dramatic narrative without interruption by arias or ensembles.[66] This approach creates a seamless flow across scenes and acts, with internal structures often employing mirroring or recapitulatory elements, such as palindromic "ring" forms where earlier events are echoed and resolved later in the cycle.[67] For instance, Siegfried's arrivals at Brünnhilde's rock in Siegfried and Götterdämmerung form a chiasmatic pair, recapitulating ancestral themes to achieve dramatic closure.[67] Harmonically, the cycle progresses from relatively diatonic foundations in Das Rheingold to heightened chromaticism and dissonance in later operas, using unresolved tensions to underscore psychological and mythical conflicts.[67] Techniques include prolonged dissonances passing through major or minor triads, chromatic voice leading that delays resolution, and progressions like the Tarnhelm motive's hexatonic cycles, which exploit enharmonic reinterpretations for ambiguity.[68] Das Rheingold's prelude establishes E-flat major diatonicism but introduces chromatic scales early, while Götterdämmerung amplifies dissonance to reflect the gods' decline.[69] Tonality remains rooted in functional harmony but is extended through fluid modulations, ambiguous key centers, and leitmotif-specific tonal profiles that align with dramatic content.[69] Global chord distributions across the cycle show a broad palette with slight emphasis on C major, but local contexts vary: the Valhalla leitmotif appears in D-flat major in Das Rheingold (over 176 measures) and shifts to E major in Die Walküre (124 measures), symbolizing evolving divine order.[69] Tonal pairings, such as E major (associated with Brünnhilde) and C major (Siegfried), drive large-scale resolutions, as in the Immolation scene's shift from E to C for fulfillment.[67] Gods' music often favors outlying scales with more accidentals, contrasting mortals' simpler tonalities to evoke otherworldly detachment.[69]Conception and Composition

Initial Concept and Influences (1840s)

In late October 1848, amid the revolutionary upheavals in Dresden, Richard Wagner drafted a prose outline for Siegfrieds Tod (Siegfried's Death), the initial kernel of what would expand into the full Ring tetralogy.[70] This single-opera concept focused on the Nibelung curse, Siegfried's betrayal and demise, and the gods' downfall, drawing directly from Germanic and Norse heroic legends to critique power's corrupting force.[71] By November 1848, Wagner had versified the libretto, presenting it to Eduard Devrient for feedback, though he resisted suggestions to clarify mythological obscurities, prioritizing mythic density over accessibility.[70] The narrative core stemmed from medieval Scandinavian sources, particularly the Völsunga Saga (c. 13th century), which supplied the Volsung clan's lineage, Sigurd's (Siegfried's) dragon-slaying, and the ring's origins as a hoard stolen from the Rhine.[72] Wagner fused this with elements from the Poetic Edda's lays, such as Fáfnismál for the curse motif and Völuspá for apocalyptic renewal, while incorporating motifs from the Middle High German Nibelungenlied (c. 1200) to emphasize heroic tragedy over supernatural fatalism.[29] These texts, accessible in 19th-century German translations, appealed to Wagner's nationalist bent, as he sought a "German" mythos distinct from Greco-Roman models, emulating the Edda's stark, stanzaic style in his verse.[22] Philosophically, Wagner's early Ring drafts reflected Ludwig Feuerbach's materialist humanism, encountered via The Essence of Christianity (1841), which posited religion as anthropomorphic projection of human needs rather than divine truth.[73] This informed the portrayal of gods as flawed, power-hungry projections doomed by their own illusions, with Siegfried embodying instinctive human vitality against Wotan's contractual tyranny—a Feuerbachian valorization of sensual love over abstract will.[74] Hegel’s dialectical progress and Proudhon's anarchism also shaped the era's sketches, framing the ring as a symbol of alienated labor and false contracts, though Wagner later critiqued these as insufficiently radical.[75] Unlike later Schopenhauerian renunciation, the 1840s conception stressed revolutionary redemption through heroic defiance, aligning with Wagner's participation in the 1849 Dresden uprising.[76]Drafting, Revisions, and Philosophical Shifts